Oregon Trail: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

m Reverted edits by 66.172.171.2 to last revision by ClueBot (HG) |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

{{see|Astor Expedition}} |

{{see|Astor Expedition}} |

||

In 1810, fur trader, entrepreneur, and one of the wealthiest men in the U.S., [[John Jacob Astor]] of the [[American Fur Company]] outfitted an expedition (known popularly as the Astor Expedition or ''Astorians'') under [[Wilson Price Hunt]] to find a possible overland supply route and trapping territory for [[fur trade|fur trading]] posts. Fearing attack by the [[Blackfoot]] Indians, the overland expedition veered south of the Lewis and Clark's route into what is now [[Wyoming]] and in the process passed across [[Union Pass]] and into [[Jackson Hole, Wyoming|Jackson Hole]]. From there they went over the [[Teton Range]] via [[Teton Pass]] and then down to the [[Snake River]] in [[Idaho]]. Upon arriving at the Snake River, they abandoned their horses, made dugout canoes and attempted to use the river for transport. Unfortunately, after a few days travel they soon discovered that the steep canyons, waterfalls and impassable rapids made travel by river impossible. Too far from their horses to retrieve them, they had to cache most of their goods and walk the rest of the way to the [[Columbia River]] where they made new boats and traveled to their newly established [[Fort Astoria]]. The expedition demonstrated that much of the route along the Snake River plain and across to the Columbia was passable by pack train or wagons with minimal improvements.<ref>{{cite web|title=Map of Astorian expedition, Lewis and Clark expedition, Oregon Trail, etc. in Pacific Northwest etc|url=http://www.oregon.com/history/oregon_trail_maps.cfm|publisher=oregon.com|accessdate=31 December, 2008}}</ref> |

In 1810, fur trader, entrepreneur, and one of the wealthiest men in the U.S., [[John Jacob Astor]] of the [[American Fur Company]] outfitted an expedition (known popularly as the Astor Expedition or ''Astorians'') under [[Wilson Price Hunt]] to find a possible overland supply route and trapping territory for [[fur trade|fur trading]] posts. Fearing attack by the [[Blackfoot]] Indians, the overland expedition veered south of the Lewis and Clark's route into what is now [[Wyoming]] and in the process passed across [[Union Pass]] and into [[Jackson Hole, Wyoming|Jackson Hole]]. From there they went over the [[Teton Range]] via [[Teton Pass]] and then down to the [[Snake River]] in [[Idaho]]. Upon arriving at the Snake River, they abandoned their horses, made dugout canoes and did not attempted to use the river for transport. Unfortunately, after a few days travel they soon discovered that the steep canyons, waterfalls and impassable rapids made travel by river impossible. Too far from their horses to retrieve them, they had to cache most of their goods and walk the rest of the way to the [[Columbia River]] where they made new boats and traveled to their newly established [[Fort Astoria]]. The expedition demonstrated that much of the route along the Snake River plain and across to the Columbia was passable by pack train or wagons with minimal improvements.<ref>{{cite web|title=Map of Astorian expedition, Lewis and Clark expedition, Oregon Trail, etc. in Pacific Northwest etc|url=http://www.oregon.com/history/oregon_trail_maps.cfm|publisher=oregon.com|accessdate=31 December, 2008}}</ref> |

||

The Astorians supply ship [[Tonquin]], after leaving supplies and men to establish [[Fort Astoria]] in early 1811 left the Columbia River for a trading expedition to [[Puget Sound]] Washington. There it was attacked and overwhelmed by Indians before being blown up-- killing all the crew and many Indians. Following the destruction of the supply ship Tonquin, American Fur Company partner [[Robert Stuart (explorer)|Robert Stuart]] lead a small group of men back east to report to Astor. The group planned to retrace the path followed by the overland expedition up the [[Columbia River|Columbia]] and [[Snake River|River]]. Fear of Indian attack near Union Pass in Wyoming forced the group further south where they discovered [[South Pass]], a wide and easy pass over the [[Continental Divide]]. The party continued east via the [[Sweetwater River (Wyoming)|Sweetwater River]], [[North Platte River]] (where they spent the winter of 1812-13) and [[Platte River]] to the [[Missouri River]] finally arriving in [[St. Louis, Missouri]] in the spring of 1813. The route they had used appeared to potentially be a practical wagon route, requiring minimal improvements, scouted from west to east, and Stuart's journals provided a meticulous account of most of the route.<ref>{{cite book|last=Rollins|first=Philip Ashton|title=The Discovery of the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart's Narratives of His Overland Trip Eastward from Astoria in 1812-13|publisher=University of Nebraska|year=1995|isbn=0-803-29234-1}}</ref> Unfortunately, because of the [[War of 1812]] and the lack of U.S. fur trading posts in the [[Oregon country]] most of the route was forgotten for more than 10 years. |

The Astorians supply ship [[Tonquin]], after leaving supplies and men to establish [[Fort Astoria]] in early 1811 left the Columbia River for a trading expedition to [[Puget Sound]] Washington. There it was attacked and overwhelmed by Indians before being blown up-- killing all the crew and many Indians. Following the destruction of the supply ship Tonquin, American Fur Company partner [[Robert Stuart (explorer)|Robert Stuart]] lead a small group of men back east to report to Astor. The group planned to retrace the path followed by the overland expedition up the [[Columbia River|Columbia]] and [[Snake River|River]]. Fear of Indian attack near Union Pass in Wyoming forced the group further south where they discovered [[South Pass]], a wide and easy pass over the [[Continental Divide]]. The party continued east via the [[Sweetwater River (Wyoming)|Sweetwater River]], [[North Platte River]] (where they spent the winter of 1812-13) and [[Platte River]] to the [[Missouri River]] finally arriving in [[St. Louis, Missouri]] in the spring of 1813. The route they had used appeared to potentially be a practical wagon route, requiring minimal improvements, scouted from west to east, and Stuart's journals provided a meticulous account of most of the route.<ref>{{cite book|last=Rollins|first=Philip Ashton|title=The Discovery of the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart's Narratives of His Overland Trip Eastward from Astoria in 1812-13|publisher=University of Nebraska|year=1995|isbn=0-803-29234-1}}</ref> Unfortunately, because of the [[War of 1812]] and the lack of U.S. fur trading posts in the [[Oregon country]] most of the route was forgotten for more than 10 years. |

||

Revision as of 15:37, 26 February 2009

| Oregon Trail | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

| Location | Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon |

| Established | 1843 |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

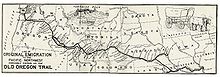

The Oregon Trail was one of the main overland migration routes on the North American continent, leading from locations on the Missouri River to the Oregon Territory. The eastern half of the trail was also used by travelers on the California Trail, Bozeman Trail and Mormon Trail which used much of the same trail before turning off to their separate destinations. To complete the journey in one traveling season most travelers left in April to May--as soon as grass was growing enough to support their teams and the trails dried out. To meet the constant needs for water, grass and fuel for campfires the trail followed various rivers and streams across the continent. In addition the network of trails required a minimum of road work to be made passable for wagons. They traveled in wagons, pack trains, on horseback, on foot, by raft and by boat to establish new farms, lives and businesses in the Oregon Territory. This territory in the early 19th century was initially jointly governed by both the United States and Britain.[1] The four to six month journey spanned over half the continent as the wagon trail proceeded about 2,000 miles (3,200 km) west through territories and land later to become six U.S. states: Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon. Extensions of the Oregon Trail were the main arteries that fed settlers into six more states: Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California, Washington, and Montana. Between 1841 and 1869 the Oregon Trail was used by settlers, ranchers, farmers, miners and business men migrating to the Pacific Northwest of what is now the United States. Once the first transcontinental railroad by the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific was completed in 1869, the use of this trail by long distance travelers rapidly diminished as the railroad traffic replaced most need for it. By 1883 the Northern Pacific Railroad had reached Portland, Oregon and most of the reason for the trail disappeared. Roads were built over or near most of the trail as local travelers traveled to cities originally established along the Oregon Trail.

(See also: Oregon Trail Interactive Map--National Park Service)[2]

History

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The first land route across what is now the United States was partially mapped by the Lewis and Clark Expedition between 1804 and 1806. Lewis and Clark believed they had found a practical overland route to the west coast, however the two passes they found going through the Rocky Mountains, Lemhi Pass and Lolo Pass, turned out to be much too difficult for wagons to pass through without considerable road work. On the return trip in 1806 they traveled from the Columbia River to the Snake River to the Clearwater River over Lolo pass again and then overland up the Blackfoot River and crossed the Continental Divide at Lewis and Clark Pass [3] and on to the head of the Missouri River. This was ultimately a shorter and faster route than the one they followed west. Unfortunately, this route had the disadvantage of being much too rough for wagons and controlled by the Blackfoot Indians who wanted no trespassers crossing their territory that could trade Iron Age goods or firearms to their enemies[citation needed]. Even though Lewis and Clark had only traveled a narrow portion of the of the upper Missouri river drainage and part of the Columbia river drainage, these were considered the two major rivers draining most of the Rocky Mountains and the expedition confirmed that there was no "easy" route through the northern Rocky Mountains as President Thomas Jefferson had hoped.

Astorians

In 1810, fur trader, entrepreneur, and one of the wealthiest men in the U.S., John Jacob Astor of the American Fur Company outfitted an expedition (known popularly as the Astor Expedition or Astorians) under Wilson Price Hunt to find a possible overland supply route and trapping territory for fur trading posts. Fearing attack by the Blackfoot Indians, the overland expedition veered south of the Lewis and Clark's route into what is now Wyoming and in the process passed across Union Pass and into Jackson Hole. From there they went over the Teton Range via Teton Pass and then down to the Snake River in Idaho. Upon arriving at the Snake River, they abandoned their horses, made dugout canoes and did not attempted to use the river for transport. Unfortunately, after a few days travel they soon discovered that the steep canyons, waterfalls and impassable rapids made travel by river impossible. Too far from their horses to retrieve them, they had to cache most of their goods and walk the rest of the way to the Columbia River where they made new boats and traveled to their newly established Fort Astoria. The expedition demonstrated that much of the route along the Snake River plain and across to the Columbia was passable by pack train or wagons with minimal improvements.[4]

The Astorians supply ship Tonquin, after leaving supplies and men to establish Fort Astoria in early 1811 left the Columbia River for a trading expedition to Puget Sound Washington. There it was attacked and overwhelmed by Indians before being blown up-- killing all the crew and many Indians. Following the destruction of the supply ship Tonquin, American Fur Company partner Robert Stuart lead a small group of men back east to report to Astor. The group planned to retrace the path followed by the overland expedition up the Columbia and River. Fear of Indian attack near Union Pass in Wyoming forced the group further south where they discovered South Pass, a wide and easy pass over the Continental Divide. The party continued east via the Sweetwater River, North Platte River (where they spent the winter of 1812-13) and Platte River to the Missouri River finally arriving in St. Louis, Missouri in the spring of 1813. The route they had used appeared to potentially be a practical wagon route, requiring minimal improvements, scouted from west to east, and Stuart's journals provided a meticulous account of most of the route.[5] Unfortunately, because of the War of 1812 and the lack of U.S. fur trading posts in the Oregon country most of the route was forgotten for more than 10 years.

The North West Co. and Hudson Bay Co.

In August 1811, three months after Fort Astor was established, David Thompson and his team of British North West company explorers came floating down the Columbia to Fort Astoria. He had just completed an epic journey through much of western Canada and most of the Columbia River drainage system. He was mapping the country for possible fur trading posts. Along the way he camped at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers and posted a notice claiming the land for Britain and stating the intention of the Northwest Company to build a fort on the site (Fort Nez Perces was later established there). In 1812 the North West company, with pressure from the War of 1812, 'bought' Astor's forts, supplies and furs on the Columbia and Snake River and started establishing more of their own.

By 1821, when armed hostilities broke out with their Hudson Bay rivals, the North West Co. was forced (by the British government) to merge with the Hudson Bay Co. The Hudson Bay Co. had nearly a complete monopoly on trading (and most governing issues) in the Columbia District, or Oregon Country as it was referred to by the Americans, and also in Rupert's Land (western Canada). That year British parliament passed a statute applying the laws of Upper Canada to the district and giving the HBC power to enforce those laws.

From 1812 to 1840 the British, through the North West and Hudson Bay Co., had nearly complete control of the Pacific Northwest and the western half of the Oregon Trail. In theory, the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812 restored the U.S. back to its possessions in Oregon territory. "Joint occupation" of the region was formally established by the Anglo-American Convention of 1818. In actuality, the British through the Hudson Bay Co. tried, more or less successfully, to discourage any U.S. trappers and traders from doing any significant trapping or trading in the Pacific Northwest. American fur trappers, traders, missionaries, and later settlers, all worked to break this monopoly. They were eventually successful.

The HBC York Factory Express, establishing another route to the Oregon territory, evolved from an earlier express brigade used by the North West Company between Fort Astoria (renamed Fort George) founded in 1811 by John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company), at the mouth of the Columbia River, to Fort William on Lake Superior. By 1825 Hudson Bay Co. started using two brigades, each setting out from opposite ends of the express route, Fort Vancouver in Washington on the Columbia River and the other from York Factory on Hudson Bay, in spring and passing each other in the middle of the continent. This established a 'quick' (about 100 days for 2600 miles (4200 km)) way to resupply their forts and fur trading centers as well as collecting the furs the posts had bought and transmitting messages between Fort Vancouver and York Factory on Hudson Bay.

The Hudson Bay Company built a new much larger Fort Vancouver in 1824 slightly upstream of Fort Astoria (now called Fort George) on the Washington side of the Columbia River (they were hoping the Columbia would be the likely Canada U.S. border). The fort quickly became the center of activity in the Pacific Northwest. Every year ships would come from London (via the Pacific) to drop off supplies and trade goods in exchange for the furs. It was the nexus for the fur trade on the Pacific Coast; its influence reached from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands, and from Russian Alaska into Mexican-controlled California. At its pinnacle in about 1840, Fort Vancouver and its Factor (manager) watched over 34 outposts, 24 ports, six ships, and about 600 employees.

When emigration over the Oregon Trail began in ernest in about 1836, for many settlers the fort became the last stop on the Oregon Trail where they could get supplies, aid and help before starting their homestead. Fort Vancouver would be the main re-supply point for nearly all Oregon trail travelers until U.S. towns could be established. Fort Colville[38] (now Colville, Washington) was established in 1825 on the Columbia river near Kettle Falls as a good site to collect furs and control the upper Columbia river fur trade. Fort Nisqually (1833-1869) was built near the present town of DuPont, Washington and was the first Hudson Bay Co. Fort on Puget sound in what would become the state of Washington. Fort Victoria, erected by Hudson’s Bay Company in 1843, was the headquarters of HBC operations in British Columbia, eventually growing into modern day Victoria, British Columbia, the capital city of British Columbia.

By 1840 The Hudson Bay Co. had three forts: Fort Hall (purchased by HBC from Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth in 1837), Fort Boise and old Fort Walla Walla (also call Fort Nez Perce) on the western end of the Oregon Trail route as well as Fort Vancouver near its terminus in the Willamette Valley. With minor exceptions they all gave substantial and often desperately needed aid to the early Oregon Trail pioneers.

When the fur trade slowed way down in 1840, due to fashion changes in men's hats, the value of the Pacific Northwest to the British (HBC) was seriously diminished. Canada had very few potential settlers who were willing to move 2500+ miles to the Pacific Northwest, although several hundred ex-trappers, British and American, and their families did start settling in Oregon, Washington and California. They also used most of the York Express route through northern Canada. In 1841 James Sinclair, on orders from Sir George Simpson, guided over 100 HBC settlers from the Red River Settlement (located at the junction of the Assiniboine River and Red River near present Winnipeg, Canada) [39] into the Oregon territory. [6]This attempt at settlement mostly failed when most of the families joined the Oregon United States settlers in the Willamette Valley, with their promise of free land and HBC free government.

In 1846 the Oregon Treaty ending the Oregon boundary dispute, was signed with Britain. The British lost the land north of the Columbia river they initially wanted. The new Canadian-U.S. boundary was established much further north at the 49th parallel. The treaty did grant Hudson Bay Co. the privilege of using the Columbia River for supplying their fur posts, clear titles to their trading post properties allowing them to be sold later if they wanted, and left the British (really Hudson Bay Co. then) with good anchorages at Vancouver, British Columbia, Victoria, British Columbia etc. on the west coast of America. It gave the United States what it mostly wanted, a 'reasonable' boundary, and a good anchorage on the West Coast in Puget Sound. While there were almost no United States settlers in the future state of Washington in 1846; the United States had already demonstrated it could induce 1000's settlers to go to the Oregon Territory; and it would be only a short time before they would vastly out number the few hundred Hudson Bay Co. Employees and HBC retirees living in Washington.

By overland travel, on what would become the Oregon trail, American missionaries and early settlers (initially mostly ex-trappers) started showing up in Oregon around 1824. Although officially the Hudson Bay Co. discouraged settlement as it interfered with their lucrative fur trade; their Chief Factor at Fort Vancouver, Dr. John McLoughlin gave very substantial help including employment until they could get established. By 1843, when 700-1000 settlers arrived, the American settlers greatly out numbered the very few nominally British settlers in Oregon. McLoughlin, despite working for the British based Hudson Bay Co., gave extensive help in the form of loans, medical care, shelter, clothing, food, supplies and seed even to United States emigrants. These new emigrants often arrived in Oregon tired, wore out, nearly penniless, with insufficient food or supplies just as winter was coming on. McLoughlin would later be hailed as the Father of Oregon.

Great American Desert

Westward expansion did not begin immediately after the Louisiana Purchase, however. Reports from expeditions in 1806 by Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and in 1819 by Major Stephen Long described the Great Plains as "unfit for human habitation" and as "The Great American Desert". These descriptions were mainly based on the relative lack of timber and surface water. The images of sandy wastelands conjured up by terms like "desert" were tempered by the many reports of vast herds of millions of bison that somehow managed to live in this "desert". [7] In the 1840s, the Great Plains appeared to be unattractive for settlement and were illegal for homesteading until well after 1846--initially it was set aside by the U.S. government for Indian settlements. The next available land for general settlement, Oregon, appeared to be free for the taking and had fertile lands, disease free climate (yellow fever and malaria were prevalent in much of the Missouri and Mississippi river drainage then) extensive uncut, unclaimed forests, big rivers, and potential seaports and only a few nominally British settlers. All one had to do was show up (a 'mere' 2,000-mile (3,200 km), six month journey across half a continent), claim what you could handle and start working and it could be yours. Thousands accepted the challenges and the opportunities.

Fur traders, trappers and Explorers

The route of the Oregon Trail began to be worked out as early as 1805 by explorers, trappers and fur traders. Fur trappers, often working for fur traders, followed nearly all possible streams looking for beaver in the 25+ years (1812-1840) the fur trade was active. Fur traders like Manuel Lisa, Robert Stuart, William Henry Ashley, Jedidiah Smith, William Sublette, Andrew Henry, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, Peter Skene Ogden, David Thompson, James Douglas, Alexander Ross, James Sinclair and other mountain men. Besides discovering and naming many of the rivers and mountains in the Intermountain West and Pacific Northwest they often kept diaries of their travels and were available as guides and consultants when the trail started to become open for general travel. The fur trade business ended just as the Oregon trail business seriously began—1840.

After 1821, the Hudson's Bay Company sent large annual parties from the Snake River Plain country and into Wyoming. The Oregon Trail west of the Rocky Mountains remained nominally in the control of Hudson's Bay Company into the 1840s.[8]

In fall of 1823, Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick led their trapping crew south from the Yellowstone River to the Sweetwater River in Wyoming. They were looking for a safe location to spend the winter. Smith reasoned since the Sweetwater flowed east it must eventually run into the Missouri River. Trying to transport their extensive fur collection down the Sweetwater, they soon found after a near disastrous canoe crash, that it was too swift and rough for water passage. On July 4, 1824 they cached their furs under a dome of rock they named Independence Rock and started their long trek to the Missouri River. Upon arriving back in a settled area they bought pack horses (on credit) and retrieved their furs. They had re-discovered the route that Robert Stuart had taken in 1813—eleven years before. Thomas Fitzpatrick was often hired as a guide when the fur trade started sputtering out starting in 1840.

The trail began to be regularly used by fur traders, missionaries, and a few general travelers starting in 1825. In 1825, the first fur trader rendezvous occurred on the Henry's Fork of the Green River on the Wyoming-Utah border. The supplies were brought in by a large party using pack trains which were then used to haul out the fur bales they had traded for. They normally used the north side of the Platte river—the same route used 20 years later by the Mormon Trail. For the next 15 years the rendezvous was an annual event moving to different locations. It allowed the fur traders to supply the needs of the trappers and their Indian allies without having the expense of building or maintaining a fort or wintering over in the cold Rockies. In 1830, William Sublette, a fur trader, brought the first wagons carrying his trading goods up the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater rivers before crossing over South Pass to a fur trade rendezvous on the Green River near the future town of Big Piney, Wyoming. He had a crew that dug out the gullies and cleared the brush where needed; thus establishing that the eastern part of most of the Oregon Trail was passable by wagons.

Fur traders tried to use the Platte River, the main route of the eastern Oregon Trail, for transport but soon gave up in frustration as its muddy waters were too shallow, crooked and unpredictable to use for water transport. The Platte was "too thick to drink and too thin to plow" and too shallow to float a canoe very long. The Platte River valley was another story as its nearly flat plain heading almost due west made an easy highway for wagons--the way west began to seem more feasible.

There were several U.S. government sponsored explorers who explored part of the Oregon Trail and wrote extensively about their explorations. Captain Benjamin Bonneville on his expedition of 1832 explored much of the Oregon trail, and brought wagons up the Platte, North Platte, Sweetwater route across South Pass to the Green River in Wyoming. In addition he explored most of the Idaho and Oregon trail to the Columbia. He had the account of his explorations in the west written up by Washington Irving in 1838. (See: "The Adventures of Captain Bonneville" [9]). John C. Fremont, and his guide Kit Carson led three expeditions from 1842 to 1846 on parts of the Oregon Trail. His explorations were written up by him and his wife Jessie Benton Fremont and were widely published. Most of these explorations were over routes that were already known by a few mountain men; but their government sponsored exploration and subsequent write ups made the routes much more widely known.

Missionaries

In 1834 the Dalles Methodist Mission, was founded by the Reverend Jason Lee just east of Mount Hood on the Columbia River. In 1836, Henry H. Spalding and Marcus Whitman traveled west to establish the Whitman Mission near modern day Walla Walla, Washington.[10] The party included the wives of the two men, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Hart Spalding, who became the first European-American women to cross the Rocky Mountains. En route, the party accompanied American fur traders going to the 1836 rendezvous on the Green River in Wyoming and then joined Hudson Bay fur traders traveling west across Idaho and Oregon to Fort Walla Walla (in Washington). The group was the first to travel in wagons all the way to Fort Hall, Idaho where they were abandoned at the urging of their guides. They used pack animals for the rest of the trip to Fort Walla Walla and then floated by boat to Fort Vancouver to get supplies before returning to start their missions in what would become northern Oregon and southern Washington. Other missionaries, mostly husband and wife teams using wagon and pack trains, established missions in the Willamette Valley, as well as various locations in the future states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho. The Missionaries example as well as their reports and speeches back home in the United States made the possibilities of the Oregon country much more widely known.

Oregon Country

Following the War of 1812, Britain and the United States signed the Treaty of Ghent, and subsequently the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, which supposedly settled border disputes and allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon country. This, in principle, opened the territory to both American and British fur traders and settlers, though it would result in a struggle between the two countries for total control of the region known as the Oregon boundary dispute. From 1812 to about 1840 the control of the territory rested almost totally in Hudson Bay (British) hands. Following the serious decline of the fur trade due to changing men's hat fashions, an increasing trickle of United States emigrants and the desire of the British for United States cooperation the British were finally convinced to compromise on a permanent boundary. In 1846, the Oregon Treaty gave complete control of the HBC Columbia District south of the present Canadian border at the 49th parallel to the United States and gave the British control from the 49th to the 54th parallel--the boundary with Alaska. In 1848 Congress formally defined the Oregon Territory which included the future states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, as well as parts of Wyoming and Montana west of the Continental Divide.

In 1843, settlers of the Willamette Valley drafted the Organic Laws of Oregon organizing land claims for the region. Married couples were granted at no cost (except for the requirement to work and improve the land) up to 640 acres (2.6 km²), and unmarried settlers could claim 320 acres (1.3 km2). As the group was a provisional government with no authority, these claims were not valid under United States or British law, but they were eventually honored by the United States in the Donation Land Act in 1850. The Donation Land Act provided for married settlers to be granted 320 acres (1.3 km²) and unmarried settlers 160 acres (0.65 km2). Following the expiration of the act in 1854. the land was no longer free, but $1.25 an acre ($3.09/hectare) with a limit of 320 acres (1.3 km²)--the same as most other unimproved government land.

Early emigrants

On May 1, 1839 a group of eighteen men from Peoria, Illinois set out with the intention to colonize the Oregon country on behalf of the United States of America and drive out the Hudson Bay Company operating there. The men of the Peoria Party were among the first pioneers to traverse most of the Oregon Trail. The men were initially led by Thomas J. Farnham and called themselves the Oregon Dragoons. They carried a large flag emblazoned with their motto "OREGON OR THE GRAVE". Although the group split up near Bents Fort on the South Platte and Farnham was deposed as a leader, nine of their members eventually did reach Oregon. [11]

In 1841 the Bartleson-Bidwell Party was the first emigrant group credited with using the Oregon Trail to emigrate west. The group set out for California, but about half the party left the original group at Soda Springs, Idaho and proceeded to the Willamette Valley in Oregon--leaving their wagons at Fort Hall.

On May 16, 1842 the second organized wagon train set out from Elm Grove, Missouri with more than 100 pioneers.[12] The party was led by Elijah White. The group broke up after passing Fort Hall with most of the single men hurrying ahead and the families following later. Despite a stated company policy to discourage U.S. emigration, John McLoughlin, Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver, offered the American settlers emergency shelter, aid, food and farming equipment on credit[citation needed].

The Great Migration of 1843

In what was dubbed "The Great Migration of 1843" or the "Wagon Train of 1843",[13][14] an estimated 700 to 1000 emigrants left for Oregon. They were led initially by John Gantt, a former US Army Captain and fur trader who was contracted to guide the train to Fort Hall for $1 per person. The winter before, Marcus Whitman had made a brutal mid-winter trip from Oregon to St. Louis to appeal a decision by his Mission backers to abandon several of the Oregon missions. He joined the wagon train at the Platte River for the return trip. When the pioneers were told at Fort Hall by agents from the Hudson Bay Company that they should abandon their wagons there and use pack animals the rest of the way, Whitman disagreed and volunteered to lead the wagons the rest of the way to Oregon. He believed the trains were large enough they could build whatever road improvements they needed to make the trip with their wagons--he was proved correct. The biggest obstacle they faced was in the Blue Mountains of Oregon where they had to cut and clear a trail through heavy timber. Nearly all of the settlers in the 1843 wagon trains arrived in the Willamette Valley by early October. A passable wagon trail now existed from the Missouri River to The Dalles, Oregon. In 1846, the Barlow Road was completed around Mount Hood providing a completely passable wagon trail from the Missouri river to the Williamette Valley--about 2000 miles.

Mormon emigration

Following persecution and mob action in Missouri, Illinois and other states, and the martyrdom of their prophet Joseph Smith in 1844 Mormon leader Brigham Young was chosen by the leaders of the Latter Day Saints (LDS) church to lead the LDS settlers west. He chose to lead his people to the Salt Lake Valley in present day Utah. In 1847 Young lead a small especially picked fast moving group of men and women from their Winter Quarters encampments near Omaha, Nebraska and their approximately 50+ temporary settlements on the Missouri River in Iowa including Council Bluffs Iowa (then called Kanesville). [15] The initial pioneering groups responsibility was to plant crops and start homes for the many thousands expected to follow. About 2,200 LDS pioneers total went that first year as they filtered in from Mississippi, Colorado California and several other states. The initial pioneers were charged with establishing farms, growing crops, building fences and herds and establishing preliminary settlements to feed and support the many thousands of immigrants expected in the coming years. The Mormons after fording the Missouri river and establishing wagon trains near what became Omaha, Nebraska followed the northern bank of the Platte River in Nebraska to Fort Laramie in present day Wyoming. Initially they started out in 1847 with trains of several thousand emigrants which were rapidly split into smaller groups to be more easily accommodated at the limited springs and good camping places on the trail. Organized as a complete evacuation from their previous homes, farms and cities in Illinois, Missouri and Iowa this group consisted of entire families with nobody left behind. The much larger presence of women and children meant the wagon trains did not try to cover as much ground in a single day as Oregon and California bound emigrants did--typically taking about 100 days to cover the 1,000 miles (1,600 km) trip to Salt Lake City. The Oregon and California emigrants typically averaged about 15 miles (24 km) per day. In Wyoming they followed the main Oregon/California/Mormon Trail through Wyoming to Fort Bridger, where they split from the main trail and followed and improved the crude path established by the ill-fated Donner-Reed party of 1846 into Utah and the Salt Lake Valley.

Between 1847 and 1860 over 43,000 LDS settlers and tens of thousands of travelers on the California Trail and Oregon trail followed Young to Utah. After 1848, the California or Oregon bound after getting repairs, new supplies or animals. then went back to the main California or Oregon trail over the Salt Lake Cutoff rejoining the trail near the future Idaho-Utah border at the City of Rocks Idaho.

To enable many poor Mormons to get to Utah from Europe and the U.S. starting in 1855 many of the LDS travelers made the trek with hand built handcarts and many fewer wagons. Guided by experienced guides, handcarts, pulled and pushed by two to four people, were as fast as the oxen pulled wagons and allowed the handcart pioneers to bring their individual 100 to 75 pounds allotment of possessions plus some food, bedding and tents to Utah. Accompanying wagons carried most of the additional food and supplies needed. Arriving in Utah the handcart pioneers were given or found jobs and accommodations by individual LDS families for the winter till they could get established. About 3,000 out of over 60,000 Mormon pioneers came across in handcarts.

Along the Mormon Trail, the Mormon pioneers established a number of ferries and made trail improvements to help later travelers and earn much needed money. One of the better known ferries was the Mormon Ferry across the North Platte near the future site of Fort Caspar in Wyoming which operated between 1848 and 1852 and the Green River ferry near Fort Bridger which operated from 1847 to 1856. The ferries were free for Mormon settlers while all others were charged a toll of from $3.00 to $8.00--just as all other ferries did.

California gold rush

In January 1848, gold was discovered in California precipitating the California Gold Rush. Its estimated that about two-thirds of the male population in Oregon went to California in 1848 to cash in on the early gold discoveries. To get there, they helped build the Lassen Branch of the Applegate-Lassen Trail by cutting a wagon road through extensive forests. (See: California Trail). Most returned with significant gold which helped jump start the Oregon economy. Over the next decade, gold seekers from the mid-west and back east started rushing overland and dramatically increased traffic on the Oregon and California Trails. The "forty-niners" often chose speed over safety and opted to use shortcuts such as the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff in Wyoming which reduced travel time by almost seven days but spanned nearly 45 miles (72 km) of desert without water, grass or material for fires.[16] Unfortunately, 1849 was also the first year of large scale cholera epidemics in the United States and the rest of the world and thousands are thought to have died along the trail on their way to California--most buried in unmarked graves in Kansas and Nebraska. The 1850 census showed this rush was overwhelmingly male as the ratio of women to men in California over 16 was about 1:18.[17] After 1849 the rush continued for several years as the California continued to produce about $50,000,000 worth of gold per year at $21/oz.[18]

Later emigration and uses of the trail

Overall it is estimated that over 400,000 pioneers used the Oregon Trail and its three primary off-shoots, the California Bozeman and Mormon Trails. The trail was still in use during the Civil War, but traffic declined after 1855 when the Panama Railroad across the Isthmus of Panama was completed. Paddle wheel steamships and sailing ships, often heavily subsidized to carry the mail, then provided rapid transport to and from the east coast, New Orleans, Louisiana etc. to and from Panama to ports in California and Oregon.

Over the years many ferries were established to help get across the many rivers on the path of the Oregon Trail. Multiple ferries were established on the: Missouri River, Kansas River, Little Blue River, Elkhorn River Loup River, Platte River, South Platte River, North Platte River, Laramie River, Green River, Bear River, two crossings of the Snake River, John Day River, Deschutes River, Columbia River as well as many other smaller streams. During peak immigration periods several ferries on any given river often competed for pioneer dollars. One way to cut costs was to buy or build your own ferry and sell it to following immigrants for what it cost you etc.. Depending upon where the pioneers started and which variation of the main trail they used these many ferries significantly increased speed and safety for Oregon Trail travelers. They increased the cost of traveling the trail by roughly $30.00 per wagon but increased the speed of the transit from about 160-170 days in 1843 to 120-140 days in 1860. The many drowning deaths that occurred on the early trail also went significantly down as dangerous and difficult crossings were made much safer.

In 1860 the Pony Express, employing riders traveling on horseback day and night, was established from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, over much of the eastern half of the Oregon Trail. They delivered mail in roughly ten days from the mid-west to California and went broke doing it when they didn't get an expected mail subsidy. Starting in 1860 several stage lines were set up carrying mail and passengers that traversed much of the route of the original Oregon Trail. By traveling day and night with many stations and changes of teams (and extensive mail subsidies) these stages could get passengers and mail from the mid-west to California in about 25 days. The First Transcontinental Telegraph line from Carson City, Nevada (a line from California to there already existed) to Omaha, Nebraska was completed in 28 October 1861 over much of the eastern half of the Oregon Trail.

As the years passed the Oregon Trail et.al. became a well known corridor from the Missouri River to the Columbia river. Offshoots of the trail also continued to grow as gold and silver discoveries, farming, lumbering, ranching, business opportunities etc. in Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Wyoming, Utah, Montana, Washington, etc. resulted in much more traffic to many areas. Traffic became more two directional as increasingly traffic went both ways to towns being established along or at the ends of the trail(s). By 1870 the population in the several states served by the Oregon trail and its offshoots increased by about 350,000 over their 1860 census levels. With the exception of most of the 180,000 population increase in California most of these people living away from the coast traveled over parts of the Oregon trail and its many extensions and cutoffs to get to their new residents.

Even before the famous cattle drives after the Civil War, the Oregon/California/Mormon/Bozeman trail were being used to drive herds of thousands of horses, sheep, cattle and goats to many locations along the Trail. According to studies by John Unruh the livestock may have been as plentiful or more plentiful than the immigrants in many years. [19]. In 1852 there was even records of a 1,500 turkey drive from Illinois (cost $0.50 ea) to California (sold at $8.00 ea). [20] The main reason for this livestock traffic was the large cost discrepancy between livestock in the mid-west and at the end of the trail in California, Oregon or Montana. They could often be bought in the mid-west for about 1/3 to 1/10th what they would fetch at the end of the trail. Large losses could occur and the drovers would still make significant profit. As the emigrant travel on the trail declined significant herds of livestock still used large segments of it to get to or from markets.

The First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869 providing faster, safer and usually cheaper travel east and west (7 days about $65), [21] Some emigrants continued to use the trail well into the 1890s and modern highways and railroads eventually paralleled large portions of the trail, including U.S. Highway 26, Interstate 84 in Oregon and Idaho and Interstate 80 in Nebraska. Contemporary interest in the overland trek has prompted the states and federal government to preserve landmarks on the trail including wagon ruts, buildings and "registers" where emigrants carved their names. Throughout the 20th century there have been a number of re-enactments of the trek with participants wearing period garments and traveling by wagon.

Oregon Trail Competitors

There were other possible migration paths for early settlers, miners or travelers to California or Oregon besides the Oregon trail prior to the establishment of the transcontinental railroads.

The longest trip was the approximately 13,600 miles (21,900 km) to 15,000 miles (24,000 km) trip on a uncomfortable sailing ship rounding the treacherous, cold and dangerous Cape Horn between Antarctica and South America and then sailing on to California or Oregon. This trip typically took four to seven months (120 to 210 days) and cost about $350-$500 dollars. The cost could be reduced to zero if you signed on as a crewman and worked as a common seaman. The hundreds of abandoned ships, whose crews had deserted in San Francisco Bay in 1849-50, showed many thousands chose to do this.

Other routes involved taking a ship to Colon, Panama (then called Aspinwall) and a strenuous, disease ridden, five to seven day trip by canoe and mule over the Isthmus of Panama before catching a ship from Panama City, Panama to Oregon or California. This trip could be done from the east coast theoretically in less that two months if all ship connections were made without waits and typically cost about $450/person. Catching a fatal disease was a distinct possibility as Ulysses S. Grant in 1852 learned when his unit of about 600 soldiers and some of their dependents traversed the Isthmus and lost about 120 men, women and children. [22] This passage was considerably speeded up and made safer in 1855 when the Panama Railroad was completed at terrible cost in money and life across the Isthmus and the treacherous, disease ridden 50 miles (80 km) trip could be done in less than a day. The time and the cost for transit dropped as regular paddle wheel steamships and sailing ships went from ports on the east coast and New Orleans, Louisiana to Colon, Panama ($80-$100), across the Isthmus of Panama by railroad ($25) and by paddle wheel steamships and sailing ships to ports in California and Oregon ($100-$150).

Another route established by Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1849 was across Nicaragua. The 120 miles (190 km) long San Juan River to the Atlantic Ocean helps drain the 100 miles (160 km) long Lake Nicaragua. From the western shore of Lake Nicaragua it is only about 12 miles (19 km) to the Pacific Ocean. Vanderbilt decided to use paddle wheel steam ships from the U.S. to the San Juan river, small paddle wheel steam launches on the San Juan river, boats across Lake Nicaragua, and a stage coach to the Pacific where connections could be made with another ship headed to California, Oregon, etc.. Vanderbilt, by under cutting fares to the Isthmus of Panama and stealing many of the Panama Railroad workers, managed to attract roughly 30% of the California bound steam boat traffic. All his connections in Nicaragua were never completely worked out before the Panama Railroad's completion in 1855. Civil strife in Nicaragua and a payment to Cornelius Vanderbilt of a 'non-compete' payment (bribe) of $56,000 per year killed the whole project in 1855.[23]

Another possible route consisted of taking a ship to Mexico traversing the country and then catching another ship out of a Acapulco, Mexico to California etc. This route was used by some adventurous travelers but was not too popular because of the difficulties of making connections and the often hostile population along the way.

The Gila Trail going along the Gila River in Arizona, across the Colorado River and then across the Sonora Desert in California was scouted by Stephen Kearny's troops and later by Captain Philip St. George Cooke's Mormon Battalion in 1846 who were the first to take a wagon the whole way. This route was used by many gold hungry miners in 1849 and later but suffered from the disadvantage that you had to find a way across the very wide and very dry Sonora Desert. It was used by many in 1849 and later as a winter crossing to California, despite its many disadvantages.

Running from 1857 to 1861 the Butterfield Stage Line won the $600,000/yr. U.S. mail contract to deliver mail to San Francisco, California. As dictated by southern Congressional members the 2,800 miles (4,500 km) route ran from St. Louis, Missouri through Arkansas, Oklahoma Indian Territory, New Mexico Territory and across the Sonora Desert before ending in San Francisco, California. Employing over 800 at its peak, it used 250 Concord Stagecoaches seating 12 very crowded passengers in three rows. It used 1800 head of stock, horses and mules and 139 relay stations to ensure the stages ran day and night. A one way fare of $200.00 delivered a very thrashed and tired passenger into San Francisco in 25 to 28 days. As quoted by New York Herald reporter, Waterman Ormsby after traveling the route: "I now know what Hell is like. I've just had 24 days of it."

Other ways to get to Oregon were: using the York Factory Express route across Canada,and down the Columbia River; ships from Hawaii, San Francisco, California or other ports that stopped in Oregon; emigrants trailing up from California, etc.. All provided a trickle of emigrants, but they were soon overwhelmed in numbers by the emigrants coming over the Oregon Trail.

The ultimate competitor arrived in 1869--the First Transcontinental Railroad which cut travel time to about seven days at a low fare (economy) of about $60.00 (economy)[24]

Routes

As the trail developed it became marked by numerous cutoffs and shortcuts from Missouri to Oregon. The basic route follows river valleys as grass and water were absolutely necessary.

While the first few parties organized and departed from Elm Grove, the Oregon Trail's primary starting point was Independence, Missouri or Westport, Kansas on the Missouri River. Later, several feeder trails lead across Kansas and some towns became starting points, including: Several towns along the Missouri River after Weston, Missouri, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Atchison, Kansas, St. Joseph, Missouri, and Omaha, Nebraska.

The Oregon Trail's nominal termination point was Oregon City, at the time the proposed capital of the Oregon Territory. However, many settlers branched off or stopped short of this goal and settled at convenient or promising locations along the trail. Commerce with pioneers going further west greatly assisted these early settlements in getting established and launched local micro-economies critical to these settlements' prosperity.

At dangerous or difficult river crossings, ferrys or toll bridges were set up and "bad" places on the trail were either 'fixed' or by-passed. Several toll roads were constructed. Gradually the trail became easier with the average trip (as recorded in numerous diaries) dropping from about 160 days in 1849 to 140 days 10 years later.

Numerous other trails followed the Oregon Trail for much of its length, including the Mormon Trail from Illinois to Utah, the California Trail to the gold fields of California and the Bozeman Trail to Montana. Because it was more a network of trails more than a single trail there were numerous variations with other trails eventually established on both sides of the Platte, North Platte, Snake and Columbia rivers. With literally thousands of people and thousands of livestock traveling in a fairly small time slot the travelers had to spread out to find clean water, 'wood', good campsites and grass. The dust kicked up by the many travelers was a constant complaint and where the terrain would allow it there may be between 20 to 50 wagons traveling more or less abreast to minimize eating each others dust.

Remnants of the trail in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the entire trail is a designated National Historic Trail (listed as the Oregon National Historic Trail).

Kansas

Starting initially in Independence/Kansas City in Missouri, the initial trail followed the Santa Fe Trail into Kansas south of the Wakarusa River. After crossing The Hill at Lawrence, it crossed the Kansas River by ferry or boats near Topeka, Kansas, and angled to Nebraska paralleling the Little Blue River until reaching the south side of the Platte River.

Nebraska

See Also: NPS Auto Tour Guide Oregon Trail Nebraska[26]

Those emigrants on the eastern side of the Missouri river used ferries and steamboats to cross over into Kansas of Nebraska. Several towns in Nebraska were used as jumping off places with Omaha, Nebraska eventually becoming a favorite after about 1855. The main branch(s) of the trails started at one of several towns on the Missouri River and then crossed Kansas and/or Nebraska to join up at the Platte River near new Fort Kearny. The fort was about 200 miles (320 km) from the Missouri river and the Oregon, California and Mormon trails and their many offshoots nearly all converged close to old Fort Kearny (established in 1848 by U.S. Army). The fort was the first chance on the trail to buy emergency supplies, do repairs, get medical aid or mail a letter. Those on the north side could usually wade the shallow Platte if they really needed to visit the fort. The Platte was too shallow, crooked, muddy and unpredictable for even a canoe to travel very far on but its valley provided an easily passable wagon corridor going almost due west with access to water, grass, buffalo and buffalo 'chips' for fire 'wood'.[27] There were trails on both sides of the muddy, about 1 mile (1.6 km) wide and shallow (2 inches (5.1 cm) to 60 inches (150 cm)) Platte River. Up to about 1870 travelers encountered hundreds of thousands of bison migrating through Nebraska on both sides of the Platte river and most travelers killed several for fresh meat and to build up their supplies of dried, 'jerked' meat for the rest of the journey. Where it was not tromped down by the buffalo or the travelers the prairie grass in many places was several feet high with only the hat of a traveler on horseback showing as they passed through the prairie grass. In most years the Indians fired the dry grass on the prairie every fall so the only trees or bushes were on islands in the Platte river. Travelers gathered and ignited dried buffalo 'chips' to cook their meals. These burned fast and it may take several bushels to get through one meal. Those traveling south of the Platte crossed the South Platte fork at one of about three ferries (in dry years it could be forded without a ferry) before continuing up the North Platte River into present-day Wyoming heading to Fort Laramie. Before 1852 those on the North side of the Platte crossed the North Platte to the south side at Fort Laramie. After 1852 they used Child's cutoff to stay on the north side to about the present day town of Casper, Wyoming where they crossed over to the south side. [28]

Notable landmarks in Nebraska include Courthouse and Jail Rocks, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff, Ash Hollow State Historical Park etc. For a more complete listing and driving directions see Nebraska's branch of Oregon-California trail Association [29]

Wyoming

The emigrant trails followed the North Platte River out of Nebraska into Wyoming. The next major stop was Fort Laramie at the junction of the Laramie River and the North Platte River. Fort Laramie was a fur trading outpost formally named Fort John that was later purchased by the U.S Army to protect travelers on the trails. [30].

Fort Laramie was the end of most Cholera outbreaks which killed thousands along the lower Platte from 1849 to 1855. Spread by cholera germs in fecal contaminated water, cholera caused massive diarrhea leading to massive dehydration and death. In those days its cause and cure was unknown, and it was often fatal. It is believed that the swifter flowing rivers in Wyoming helped prevent the germs from spreading. [31]

Continuing up the North Platte and crossing many small swift flowing creeks they traversed over to the Sweetwater River which would have to be crossed up to nine times before the trail left the Sweetwater valley and crossed over the Continental Divide at South Pass. From South Pass the trail followed Big Sandy creek(s) till it hit and crossed the Green River--three to five ferries were in use there during peak travel periods. The swift and treacherous Green river was usually at high water in July and August and it was a dangerous crossing. The main trail continued on in an approximate southwest direction until it encountered Blacks Fork of the Green River and Fort Bridger. Here, the Mormon Trail continued southwest to Salt Lake City, Utah while the main trail turned almost due north before turning northwest and following the Little Muddy Creek valley over the Bear River Divide to the Bear River valley.[32]

Over time, two major heavily used cutoffs were established. The Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff was established in 1844 and cut about 70 miles (110 km) off the main route. It left the main immigrant trail near about South Pass and headed almost due west crossing about 45 miles (72 km) of desert before reaching the Green River near the present town of La Barge and then crossing a mountain range to connect with the main trail near Cokeville in the Bear River valley. [33] The Lander Road was established and built by government contractors in 1858. It departed the main trail at Burnt Ranch, crossed the Continental Divide north of South Pass and crossed the Green River near the present town of Big Piney finally passing over 8,800 feet (2,700 m) Thompson Pass in the Salt River Mountains and descending into Star Valley the present town of Smoot. The road continued through Star Valley and turned near the present town of Auburn, Wyoming and and entered into Idaho proceeding to meet the main trail at Fort Hall.[34]. [35]

Numerous landmarks are located along the trail in Wyoming including Independence Rock, Ayres Natural Bridge and Register Cliff.

Utah

In 1847, Brigham Young and the first Mormon pioneers departed from the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger and established a trail to Salt Lake City, Utah. In 1848, the Salt Lake Cutoff was established, providing a path north from Salt Lake City and rejoining the Oregon and California Trails near the City of Rocks at the Utah/Idaho border. Many later emigrants used Salt Lake City as an intermediate stop for fresh fruits and vegetables, supplies, fresh livestock and repairs. The overall distance to California or Oregon was approximately the same whether one "detoured" to Salt Lake City or not.

Idaho

See Also:

- NPS Idaho auto tour of Oregon Trail[36]

- Idaho State Historical Society Tour of Oregon Trail[37]

- Map of Oregon Trail in Idaho[38]

The main Oregon and California Trail went almost due north from Fort Bridger to the Little Muddy Creek where it passed over the Bear River Mountains to the Bear River (Utah) valley which it followed northwest into the Thomas Fork area where the trail crossed over the present day Wyoming line into Idaho. In the Eastern Sheep Creek Hills on the Thomas Fork valley the emigrants encountered Big Hill. Big Hill had a tough ascent often requiring doubling up of teams and a very steep and dangerous descent. [39] In 1852 Eliza Ann McAuley found and with help developed the McAuley Cutoff which bypassed much of the difficult climb and descent of Big Hill. About 5 miles (8.0 km) on they passed present day Montpelier, Idaho which is now the site of a The National Oregon-California Trail Center[40]. They followed the Bear River northwest to present day Soda Springs, Idaho. The soda springs here were a favorite attaction of the pioneers who marveled at the carbonated water and chugging steamboat springs. Many stopped and did their laundry in the hot water as their was usually plenty of good grass. [41]Just west of Soda Springs the Bear river turned southwest and the main trail turned northwest to follow the Portneuf River valley to Fort Hall (Idaho). Fort Hall, on the Snake River, was an old fur trading post established in 1834 and owned by the British Hudson Bay Company. Here nearly all travelers were given some aid and supplies if they were available and needed. Here mosquitoes were constant pests and travelers often mention their animals covered with blood from blood sucking mosquitoes. The route from Fort Bridger to Fort Hall was about 210 miles (340 km) taking nine to twelve days.

At Soda Springs was one branch of Lander's Road (established and built with government contractors in 1858) which had gone west from present day Auburn, Wyoming and then proceeded northwest into Idaho up Stump Creek canyon for about ten miles before one branch turned almost 90 degrees and proceeding southwest to Soda Springs. Another branch headed almost due west past Grey’s Lake to rejoin the main trail about 10 miles (16 km) west of Fort Hall.

On the main trail about 5 miles (8.0 km) west of Soda Springs Hudspeth's Cutoff (est. 1849 and used mostly by California trail users) took off from the main trail heading almost due west and by-passed Fort Hall. It rejoined the California trail at Cassia Creek near the City of Rocks (now a national reserve and Idaho State park). [42] Hudspeth's Cutoff had five mountain ranges to cross and took about the same amount of time as the main route to Fort Hall but many took it thinking it was shorter. It's main advantage was that it did spread out the traffic on busy years and made more grass available. (For Oregon-California trail map up to junction in Idaho see: Oregon National Historic Trail Map NPS [43])

West of Fort Hall the trail traveled about 40 miles (64 km) on the south side of the Snake River southwest past American Falls, Massacre Rocks, Register Rock and Coldwater Hill till near present day Pocatello, Idaho. Near the junction of the Raft River and Snake River (Idaho) the California Trail diverged from the Oregon Trail by leaving the Snake River and following the small and short Raft River about 65 miles (105 km) southwest past present day Almo, Idaho. It then passed through the City of Rocks and over Granite Pass where it went southwest along Goose Creek, Little Goose Creek, and Rock Spring Creek. It went about 95 miles (153 km) through Thousand Springs Valley, West Brush Creek, Willow Creek, before arriving at the Humboldt River in northeastern Nevada near present day Wells, Nevada. (Northern Nevada and Utah, Southern Idaho Tail Map[44]) The California trail proceeded west down the Humboldt before reaching and crossing the Sierra Nevadas.

There were only a few places where the Snake River has not buried itself deep in a canyon. There were fewer yet where the river slowed down enough to make a crossing reasonably possible. Two of these possible fords were near Fort Hall where the travelers on the Oregon Trail North Side Alternate (established about 1852) and Goodale’s Cutoff (established 1862) crossed the Snake to travel on the north side. Nathaniel Wyeth, the original founder of Fort Hall in 1834, writes in his diary that they found a ford across the Snake River 4 miles (6.4 km) southwest of where he founded Fort Hall. Another possible crossing was a few files up stream of Salmon Falls where some intrepid travelers floated their wagons and swam their stock across to join the north side trail. Some didn't make it and lost their wagons and teams over the falls. The trails on the north joined the trail from Three Island Crossing about 17 miles (27 km) west of Glenns Ferry on the north side of the Snake River. [45] (For map of North Side Alternate see: [46])

Goodale's Cutoff, established in 1862, formed a spur of the Oregon Trail. This cutoff had been used as a pack trail by Indians and fur traders for many years, and emigrant wagons had traversed parts of the eastern section as early as 1852. The 230 miles (370 km) cutoff headed north from Fort Hall toward Big Southern Butte following the Lost River (Idaho) part of the way. It passed near the present-day town of Arco, Idaho and wound through the northern part of Craters of the Moon National Monument. From there it went southwest to Camas Prairie, and ended at old Fort Boise on the Boise River. This journey typically took two to three weeks and was noted for its very rough, lava restricted roads and extremely dry climate which tended to dry the wooden wheels on the wagons leading to the iron rims falling off the wheels. Loss of wheels caused many abandoned wagons to lie along the route. It rejoined the main trail east of Boise. Goodale's Cutoff is visible at many points along Idaho Highway 20, Idaho Highway 26 and Idaho Highway 93 between Craters of the Moon National Monument and Carey, Idaho.[47]

From the present site of Pocatello the trail proceeded almost due west on the south side of the Snake River for about 180 miles (290 km). On this route they passed Cauldron Linn rapids, Shoshone Falls, and two falls near the present city of Twin Falls, Idaho and Upper Salmon Falls on the Snake River. At Salmon Falls there were often a hundred or more Indians fishing who would often trade for their salmon--a welcome treat. The trail continued west to Three Island Crossing (near present day Glenns Ferry, Idaho). [48] [49]Here most emigrants used the divisions of the river caused by three islands to cross the difficult and swift Snake River by ferry or by driving or sometimes floating their wagons and swimming teams across. The crossings was doubly treacherous because there were often hidden holes in the river bottom which if your team dropped into them the wagon may overturn and the wagon and team would end in a large snarl with the drivers in the river or sometimes fatally tangled up in the snarl. Guides familiar with the river were an excellent idea and young Indians often helped get the teams and wagons across for a small fee or trade item. Before ferries were established (1867?) there were drownings here nearly every year. Today there is a Idaho State Park and Interpretive Center there and on the second Saturday of August a re-enactment of a crossing.[50] The north side of the Snake had better water and grass than the south. The trail from Three Island Crossing to old Fort Boise was about 130 miles long before getting into the welcome relief of the usually lush Boise River valley and the next required crossing of the Snake River near old Fort Boise. This last crossing of the snake was usually done on bull boats and swimming the stock across. Others would chain a large string of wagons and teams together with a set of teams on a long chain in front. The theory was that the front teams, usually oxen, would get out of water first and with good footing help pull the whole string across. How well this worked in practice is not stated. Again it was not unusual for young Indian boys to be hired to drive and ride the stock across the river--they at least knew how to swim unlike many pioneers. Today’s Idaho Interstate 84 roughly follows the Oregon trail till it leaves the Snake River near Burley, Idaho From there Interstate 86 to Pocatello roughly approximates the trail. Highway 30 from there to Montpelier Idaho follows roughly the path of the Oregon Trail.

Starting in about 1848 the South Alternate of Oregon Trail (also called the Snake River Cutoff) was developed as a spur off the main trail. It ran from Three Island Crossing, traveling down the south side of the Snake River, till it rejoined the trail near present day Ontario, Oregon. It hugged the southern edge of the Snake River canyon and was a much rougher trail with less water and grass; requiring occasional steep descents and ascents with the animals down into the Snake River canyon to get water. It did avoid two crossings of the Snake River though. [51] Today's Idaho State Route 78 roughly follows the path of the South Alternate route of the Oregon Trail.

In about 1860 the Kelton Road was developed from roughly the City of Rocks to about 15 miles (24 km) west of the California Trail junction. It used the main Oregon Trail from there to Boise cross to the North side at Three Island Crossing or Glenn's Ferry. It was used primarily as a freight road for carrying freight to newly discovered mining districts of the Idaho Territory from both Salt Lake City using the Salt Lake Cutoff and California using the California trail in reverse. After the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869 the Kelton Road was extended to the railroad and used as a freight road from the railroad to Boise, Idaho and the northern Idaho mines. They built relay stations at about ten mile intervals on the trail from Kelton to Boise to change their teams. (Kelton Road map with stations[52]) [53] Today Kelton, Utah, which developed on one end of this road near the railroad, is a ghost town.

Starting in about 1848 the Salt Lake Cutoff allowed Oregon and California Trail travelers to continue on past Fort Bridger to Salt Lake City, Utah to get new supplies of animals and then to return to the main trail. This trail rejoined the main trail near the City of Rocks Idaho and was used for many years by settlers and travelers in Idaho and Oregon to get supplies from Salt Lake City--the closest big city.

Oregon

Once across the Snake river ford near old Fort Boise the weary travelers traveled across what would become the state of Oregon. The trail then went to the Malheur River and then past Farewell Bend on the Snake river, up the Burnt River (Oregon) canyon and northwest to what's now the La Grande, Oregon valley before hitting the Blue Mountains (Oregon). The 1843 settlers cut a wagon road over these mountains making them passable for the first time to wagons. For five years the trail went to the Whitman Mission near old Walla Walla Washington until 1847 when the Whitmans were murdered by Indians. At Fort Walla Walla some built rafts or hired boats and started down the Columbia others continued west in their wagons till they hit Dalles. After 1847 the trail bypassed the closed mission and headed almost due west to present day Pendelton, Oregon crossing the Umatilla River, John Day River, and Deschutes River before arriving at The Dalles, Oregon. Modern Interstate 84 in Oregon roughly follows the original Oregon Trail from Idaho to the Dalles.

Arriving at the Columbia at the Dalles and stopped by the Cascade Mountains and Mount Hood, some gave up their wagons or disassembled them and put them on boats or rafts for a trip down the Columbia River. Transiting the Cascade's Columbia River Gorge with its (then) multiple rapids and treacherous winds they would have to make the 1.6 miles (2.6 km) portage around the famous Cascade Rapids before coming out near the Willamette River where Oregon City, Oregon was located. The pioneers livestock could be driven around Mount Hood on the narrow, crooked and rough Lolo Pass (Oregon) trail. (A clickable tour across Oregon's part of the Oregon Trail is available at the following reference) [54]

Several Oregon Trail branches and route variations over time led to the Willamette Valley. Besides boats or rafts down the Columbia River, the most popular was the Barlow Road carved though the forest around Mount Hood from The Dalles in 1846 as a toll road at $5.00 a wagon $0.10/ea. for livestock. It was rough and steep with poor grass but still cheaper and safer than floating goods, wagons and family down the dangerous Columbia River.

In Central Oregon there was the Santiam Wagon Road (established 1861) roughly paralleling Oregon highway 20 to the Willamette valley. The Applegate Trail (established 1846) cutting off the California Trail from the Humboldt River in Nevada crossed part of California before cutting north to the south end of the Willamette valley. U.S. Route 99 through Oregon (now Oregon Route 99) and Interstate 5 through Oregon roughly follow the original Applegate trail's route.

Travel equipment

The Oregon Trail was too long and arduous for the standard Conestoga wagons commonly used at that time in the Eastern United States and on the Santa Fe Trail. Their 6,000 pounds (2,700 kg) capacity was larger than needed and the large teams these wagons required could not navigate the tight corners often found on the Oregon trail.

This led to the rapid development of prairie schooners. This wagon was approximately half the size of the larger wagon, weighed about 1,300 pounds (590 kg) empty with about 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg) of capacity and about 88 square feet (8.2 m2) of storage space in a 11 feet (3.4 m) long, 4 feet (1.2 m) wide, by 2 feet (0.61 m) high box. The wagons were manufactured in quantity by companies like Studebaker at a "reasonable" price, with new wagons costing between $85.00 and $170.00. The canvas covers of the wagons were doubled and treated with linseed oil to help keep out the rain, dust and wind, though the covers eventually tended to leak anyway. The typical wagon with 40 to 50 inch (1.0-1.3 m) diameter wheels could easily move over rough ground and rocks without high centering and even over most tree stumps if required. In practice it was found that the "standard" farm wagon built by a company or wagon maker (wainwright) of good reputation usually worked just as well as prairie schooners and had only to be fitted with bows and a canvas cover to be ready. Wagons were generally reliable if maintained, but sometimes broke down and had to be repaired or abandoned along the way. One wagon could carry enough food for six months travel for four or five as well as a short list of 'luxury items'. As a bonus, they also provided protection from bad weather and you didn't have to reload everything on cantankerous mules or oxen every morning.

Despite the popular image of Hollywood movies from 60 to over 70% traveled West with Ox pulled teams with mule teams second and almost no horses. This was true for many reasons. An ox team was slower (about 2-3 miles/hour) but: cheaper to buy ($25 to $85 per yoke), could pull more, survive better on the sparse grass often found along the trail and was often tamer and easier to handle after they were trained. As a bonus, if an oxen ran off at night it was usually easier to find and catch and the Indians were less interested in stealing them. Losing your team on the trail was a major disaster and even if you could find or buy a replacement (not a sure thing) it wouldn't be cheap.

The recommended amount of food to take for per adult was 150 pounds (70 kg) of flour, 20 pounds (9 kg) of corn meal, 50 pounds (25 kg) of bacon, 40 pounds (20 kg) of sugar, 10 pounds (5 kg) of coffee, 15 pounds (7 kg) of dried fruit, 5 pounds (2 kg) of salt, half a pound (0.25 kg) of saleratus (baking soda), 2 pounds (1 kg) of tea, 5 pounds (2 kg) of rice, and 15 pounds (7 kg) of beans. This material was usually kept in a water tight containers or barrels to minimize spoilage. The "usual" meal for breakfast, lunch and dinner along the trail was bacon, beans and biscuits or bread.[55] The typical cost of enough food for four people for six months was about $150.00. [56]

The amount of food required was lessened if beef cattle, calves or sheep were taken along for a walking food supply. Nearly all travelers prior to the 1870s run into vast herds of buffalo in the early part of the trip in Nebraska some of which were typically killed and used for fresh meat. Often several buffalo were killed and jerked into dried meat that could be kept without spoiling. In general, wild game could not be depended on for a regular source of food but when found it was relished as a welcome change in a very monotonous diet. Travelers could hunt antelope, buffalo, sage hens, trout, and occasionally elk, bear, duck, geese, salmon and deer along the trail. Most travelers carried a rifle or shotgun and spare powder, lead and primers for hunting game and protection against snakes and Indian attacks. When they got to the Snake River and Columbia River areas they would often trade with the Indians for salmon--a welcome change. The Indians in Oregon often traded potatoes and other vegetables they had learned to grow from the missionaries. Some families took along milk cows, goats, and chickens (penned in crates tied to the wagons). Additional food like pickles, canned butter, cheese or pickled eggs were occasionally carried, but canned goods were expensive and food preservation was primitive, so few items could be safely kept for the duration of the trip.

Cooking along the trail was typically done over a campfire dug into the ground and made of wood, buffalo 'chips', willow or sage brush. Flint and steel were used to start fires. Some carried matches in water tight containers to help start fires. Fire was typically 'borrowed; from a neighbor for ease of starting. Cooking typically required simple cooking utensils such as butcher knives, large spoons, spatulas, ladles, Dutch ovens, pots and pans, grills, spits, coffee pots and a iron tripod to suspend the pans and pots over the fire. Some brought small stoves, but these were often jettisoned along the way as too heavy and unnecessary. Wooden or canvas buckets were brought for carrying water, and most travelers carried canteens and/or water bags for daily use. At least one water barrel was brought, but it was usually nearly empty to minimize weight (some water in it preventing it from drying out and losing its water tightness); it was only filled for long waterless stretches. Some brought a new invention--an India Rubber combination mattress and water carrier. [57] Shovels, crow bars, picks, saws, hammers, axes and hatchets were used to clear or make a road, build a raft or bridge, or repair the wagon where necessary.

Tobacco was popular, both for personal use and for trading with Indians. Each person brought at least two changes of clothes and multiple pairs of boots (two to three pair were often wore out on a trip). About 25 pounds of soap was recommended for a party of four for washing yourself and your clothes. A wash board and tub was also usually included to aid in washing clothes. Wash days typically only occurred once or twice a month or less when a good place to stop with good grass, water and 'wood' were found. Most wagons carried tents for sleeping, though in good weather most would sleep outside of the tent and wagon. A thin fold up mattress, blankets, pillows, canvas or rubber gutta percha ground covers were used for sleeping at night. Sometimes an unfolded feather bed mattress was brought for the wagon if there were pregnant women or very young children along. The wagons had no springs, and the ride along the trail was very rough. Despite modern depictions, almost nobody actually rode in the wagons; it was too dusty, too rough and hard on the livestock. The ox drivers walked alongside their oxen and mules were often guided by riding one that was hooked to the wagon.