President's House (Philadelphia)

| President's House in Philadelphia | |

|---|---|

Third Presidential Mansion, occupied by George Washington, November 1790–March 1797 and by John Adams, March 1797–May 1800. | |

| |

| Former names | 190 High Street Masters-Penn House Robert Morris Mansion |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| Address | 524–30 Market Street |

| Town or city | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 39°57′02″N 75°09′00″W / 39.9505°N 75.1501°W |

| Construction started | 1767[1] |

| Demolished | 1832 / 1951 |

| Client | Mary Lawrence Masters |

The President's House in Philadelphia was the third U.S. Presidential Mansion. George Washington occupied it from November 27, 1790, to March 10, 1797, and John Adams occupied it from March 21, 1797, to May 30, 1800.

The house was located one block north of the Pennsylvania Statehouse, now known as Independence Hall, and was built by Mary Masters, a widow, around 1767. During the 1777–1778 British occupation of Philadelphia, it was headquarters for General Sir William Howe and the British Army. The British abandoned the city in June 1778, and the house became headquarters for Military Governor Benedict Arnold.

Philadelphia served as the national capital from 1790 to 1800 while Washington, D.C. was under construction. During this time, the house was owned by Revolutionary War financier and Founding Father Robert Morris, who gave the house to George Washington. Washington brought nine enslaved Africans from Mount Vernon to work in his presidential household.[2]

The house also served as the executive mansion for the second U.S. president, John Adams, who later moved to the not-yet-completed White House in Washington, D.C., on November 1, 1800.

In 1951, confusion over the exact location of the Philadelphia President's House led to its surviving walls being unknowingly demolished.[3] Advocacy by historians and African American groups resulted in the 2010 commemoration of the site.

History

[edit]The three-and-a-half-story brick mansion on the south side of Market Street was built in 1767 by widow Mary Lawrence Masters.[1] In 1772, she gave it as a wedding gift to her elder daughter, Polly, who married Richard Penn, the lieutenant-governor of the colony and a grandson of William Penn. Richard Penn entertained delegates to the First Continental Congress at the house, including George Washington. Penn was entrusted to deliver Congress' Olive Branch Petition to King George III in a last-ditch effort to avoid war between Great Britain and the colonies. Penn, his wife, and in-laws departed for England in July 1775.[4]

During the British occupation of Philadelphia from September 1777 to June 1778, the house was headquarters for General Sir William Howe. Following the British evacuation, it housed the American military governor, Benedict Arnold, and it was here that Arnold began a secret and treasonous correspondence with the British. The next resident was John Holker, a purchasing agent for the French, who were American allies in the war. During Holker's residency the house suffered a fire. Financier Robert Morris purchased the house from Richard Penn in 1781, although transfer of the deed was delayed because of the war.

Morris refurbished and expanded the house, and lived there while Superintendent of Finance. Washington lodged with Morris during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. In 1790, Morris gave up the house for his friend to use as the Executive Mansion, and moved to the house next door.

President Washington occupied the Philadelphia President's House from November 1790 to March 1797, and President Adams occupied it from March 1797 to May 30, 1800. Adams then visited Washington, D.C., to oversee the transfer of the federal government and returned to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts for the summer. He moved into the not yet completed White House on November 1, 1800, the first U.S. president to live there, and occupied it for just over four months. Thomas Jefferson won the Presidential election of 1800 and was inaugurated on March 4, 1801.

Post-presidential

[edit]Following President Adams's 1800 departure, the house was converted into Francis's Union Hotel. Hardware merchant Nathaniel Burt purchased the property in 1832,[5] and gutted the house, inserting three narrow stores between its exterior walls. He and his descendants owned these stores for just over a century.[3]

Merchant John Wanamaker opened his first clothing store, "Oak Hall," at 536 Market Street in 1861. He expanded into the stores at 532 and 534 Market, and eventually built up their height to six stories.[6] The party wall between 530 and 532 Market was the four-story west wall of the President's House, and would have been incorporated into the expanded "Oak Hall."[3] "Oak Hall" was demolished in 1936, leaving two stories of the party wall intact.[3] The four-story east wall of the President's House was the party wall shared between 524 and 526 Market Street.[3] This survived intact until 1951.

What was left of the Burt stores, along with the house's surviving walls, were demolished in 1951 for the creation of Independence Mall.[3] A public toilet was built upon the house's footprint in 1954, later demolished,[2] and replaced by a memorial site in 2010 after archeology studies.

President Washington in Philadelphia

[edit]

"The Washington Family" by Edward Savage, painted between 1789 and 1796, shows (from left to right): George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington, Nelly Custis, Martha Washington, and an enslaved servant (probably William Lee or Christopher Sheels).

President Washington, First Lady Martha Washington, and two of her grandchildren, "Wash" Custis and Nelly Custis, lived in the house. He had an initial household staff of about 24, eight of whom were enslaved Africans, plus an office staff of four or five, who also lived and worked there. The house was too small for the 30-plus occupants, so the President made additions:

"...a large two-story bow to be added to south side of the main house making the rooms at the rear thirty-four feet in length, a long one-story servants' hall to be built on the east side of the kitchen ell, the bathtubs to be removed from the bath house's second floor and the bathingroom turned into the President's private office, additional servant rooms to be constructed, and an expansion of the stables."[1]

Major actions as president

[edit]- Oversaw the establishment of the federal judiciary

- Oversaw the establishment, location and planning of the future District of Columbia.

- Quashed the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania.

Use of slave labor

[edit]

Washington brought eight slaves from Mount Vernon to Philadelphia in 1790: Moll, Christopher Sheels, Hercules, his son Richmond, Oney Judge, her half-brother Austin, Giles, and Paris.[7]

Pennsylvania had begun a gradual abolition of slavery in 1780, freezing the number of slaves in the state and granting freedom to their future children. The law did not free anyone at once; its gradual abolition was to be accomplished over decades as the enslaved aged and died off. The law allowed slaveholders from other states to hold personal slaves in Pennsylvania for six months, but empowered those same enslaved to claim their freedom if held beyond that period.

Washington recognized that slavery was unpopular in Philadelphia, but argued (privately) that he remained a resident of Virginia and subject to its laws on slavery. He gradually replaced most of the President's House enslaved servants with German indentured servants, and rotated the others in and out of the state to prevent them from establishing an uninterrupted six-month residency. He was also careful that he himself never spent six continuous months in Pennsylvania. Joe (Richardson) was the only slave added to the presidential household. He was brought up from Virginia in 1795, following Austin's December 20, 1794, death in Maryland.[8]

Oney Judge

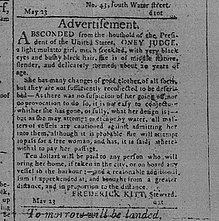

[edit]Oney Judge was the personal slave of Martha Washington, and was about 17 when she was brought to the President's House in 1790. More is known about her than any of the other enslaved because she gave two interviews to abolitionist newspapers in the 1840s. She escaped to freedom from the President's House in May 1796, and was hidden by Philadelphia's free-black community.[9] The President's House steward placed runaway advertisements in Philadelphia newspapers offering a reward for her recapture. She was smuggled aboard a ship to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where she was recognized on the street by a friend of the Washingtons. Through intermediaries, Washington attempted to convince her to return, but she refused unless she was guaranteed her freedom upon their deaths.[10] Martha Washington's nephew, Burwell Bassett, traveled to Portsmouth in 1798. He lodged with Senator John Langdon and revealed his plan to abduct Judge. Langdon sent word for her to go into hiding, and Bassett was forced to return without her.

Hercules

[edit]Hercules was the chief cook at Mount Vernon in 1786, and was brought to the President's House in November 1790 to run the kitchen.[11] He requested that his 12-year-old son Richmond accompany him, but Richmond spent only a year in Philadelphia. Much of what is known about Hercules comes from a nostalgic and affectionate account by Martha Washington's grandson, who presumed that "Uncle Harkless" had been content in slavery.[11] Stephen Decatur Jr., author of The Private Affairs of George Washington (1933), wrote that Hercules had escaped to freedom in Philadelphia at the end of Washington's presidency, and for 79 years this was accepted as true. Research published in 2012 establishes that Hercules escaped to freedom from Mount Vernon on February 22, 1797, Washington's 65th birthday.[12]

Hercules left behind Richmond and daughters Evey and Delia at Mount Vernon.[11] There was a reported sighting of him in New York City in 1801,[13] but by then he had been freed under the terms of George Washington's will. The mystery of his journey after escaping Mount Vernon seems to have been solved in 2019.[14] Genealogist Sara Krasne, searching records at the Westport Historical Society in Massachusetts, found a Hercules Posey, born in Virginia, who died of consumption on May 15, 1812, age 64, and was buried in the Second African Burying Ground in New York City.[14] John Posey was the Virginia slaveholder who mortgaged Hercules to George Washington in 1767, and later defaulted on the loan.[15]

President Adams in Philadelphia

[edit]Major actions as president

[edit]- Built six frigates for the United States Navy.

- Established the modern United States Marine Corps.

- French seizure of more than 300 American ships and the XYZ Affair's demand for bribes led to the Quasi War with France.

- Completed construction of the White House and much of the United States Capitol.

Archaeology and advocacy

[edit]Liberty Bell Center

[edit]As the turn of the 21st century approached, a major new building to house the Liberty Bell was being planned for Independence Mall. Nearly the length of a football field, including its 40 ft (12 m) porch, the Liberty Bell Center would stretch along the east side of Sixth Street from Chestnut Street almost to Market Street.[16]

2000 archaeology

[edit]

An archaeological excavation of the Liberty Bell Center's footprint was undertaken in November and December 2000.[1] The most significant President's House-related artifact uncovered was the bottom half of its icehouse pit.[17] A technological marvel built by Robert Morris in the early 1780s, the icehouse had been a windowless building erected over an octagonal stone-walled pit, 13 ft (4.0 m) in diameter and 18 ft (5.5 m) deep.[18]: 46–53 In midwinter the pit would be packed with blocks of ice harvested from the Schuylkill River.[19] The icehouse provided refrigeration for most of the year:

The Door for entering this Ice house faces the north, a Trap Door is made in the middle of the Floor through which the Ice is put in and taken out. I find it best to fill with Ice which as it is put in should be broke into small pieces and pounded down with heavy Clubs or Battons such as Pavers use, if well beat it will after a while consolidate into one solid mass and require to be cut out with a Chizell or Axe. I tried Snow one year and lost it in June. The Ice keeps until October or November and I believe if the Hole was larger so as to hold more it would keep untill Christmas..."[20]

The truncated icehouse pit was measured and photographed by the National Park Service, and then reburied.[18] It lies beneath the concrete slab of the Liberty Bell Center's floor.

Presidential slavery campaign

[edit]

Abolitionists gave the Liberty Bell its name in the 1830s, and adopted it as their emblem for the movement to end slavery in America.[3] In 1790, Washington brought eight enslaved Africans from Mount Vernon to Philadelphia to work in his presidential household. He directed that his white coachman and enslaved stableworkers be housed in a building behind the kitchen.[3] The footprint of this building was located under the porch of the planned Liberty Bell Center, about five feet from the LBC's main entrance.[18]: 46–50 The Liberty Bell Center was under construction in January 2002, when the Historical Society of Pennsylvania published Edward Lawler, Jr.'s research on the President's House,[3] including the revelation that future visitors to the LBC would "walk over" the footprint of Washington's "slave quarters" as they entered the new building.[21]

In a March 12, 2002, evening lecture at the Arch Street Friends Meeting House and an interview the next morning on WHYY-FM, Philadelphia's National Public Radio affiliate, UCLA historian Gary Nash scathingly criticized Independence Park for its refusal to interpret the enslaved Africans at the President's House site.[22] Independence National Historic Park (INHP) Superintendent Martha Aikens countered with an op-ed proposing that the enslaved be interpreted at the Germantown White House, some eight miles away.[23] Nash's anger inspired the founding of the Ad Hoc Historians, a group of Philadelphia-area scholars whose immediate concern was the interpretation for the under-construction Liberty Bell Center.[24]

The public controversy also led to the formation of two African-American groups that advocated for the enslaved: Avenging the Ancestors Coalition, founded by attorney Michael Coard;[25] and Generations Unlimited, founded by local historian Charles Blockson and activist Sacaree Rhodes.[18] Coard delivered a petition signed by 15,000 people to Independence Park urging it to build a memorial to the President's House and Washington's slaves.[18]: 52

The Philadelphia Inquirer published a front-page, banner-headlined article on Sunday, March 24, 2002, "Echos of Slavery at Liberty Bell Site."[21] This included a terse statement from Independence Park: "The Liberty Bell is its own story, and Washington's slaves are a different one better told elsewhere."[21] The Inquirer followed up with more major articles, and its lead editorial on March 27 was titled: "Freedom and Slavery. Just as they coexisted in the 1700s, both must be part of the Liberty Bell's story."[24] The Inquirer published an op-ed by Nash and St. Joseph's University historian Randall Miller on Sunday, March 31, alongside one by Rutgers University historian Charlene Mires. The next day, the Associated Press issued a national story: "Historians Decry Liberty Bell Site."[24]

NPS Chief Historian Dwight Pitcaithley wrote to Independence Park's superintendent, urging her to consider a different perspective:

The contradiction in the founding of the country between freedom and slavery becomes palpable when one actually crosses through a slave quarters site when entering a shrine to a major symbol of the abolition movement....How better to establish the proper historical context for understanding the Liberty Bell than by talking about the institution of slavery? And not the institution as generalized phenomenon, but as lived by George Washington's own slaves. The fact that Washington's slaves Hercules and Oney Judge sought and gained freedom from this very spot gives us interpretive opportunities other historic sites can only long for. This juxtaposition is an interpretive gift that can make the Liberty Bell "experience" much more meaningful to the visiting public. We will have missed a real educational opportunity if we do not act on this possibility.[26]

Pitcaithley read Independence Park's interpretive script for the Liberty Bell Center's exhibits, and found it disappointing. He described it as "an exhibit to make people feel good but not to think," that "works exactly against NPS's new thinking," and "would be an embarrassment if it went up."[24] Members of the Ad Hoc Historians, ATAC, and Generations Unlimited participated in a May 13, 2002, planning session on the LBC interpretation, overseen by Pitcaithley.[24] Later in the month, he assembled a panel of top NPS historians to rewrite the interpretation.[24]

President's House site

[edit]The Philadelphia City Council and the Pennsylvania General Assembly each passed resolutions urging the National Park Service to interpret the story of the enslaved Africans at the President's House site.[27] In July 2002, a provision was inserted into the FY2003 Department of Interior appropriation bill requiring NPS to study this and report back to the U.S. Congress.[2]

A design process for the President's House site began in October 2002, although it was boycotted by Generations Unlimited. Preliminary designs for the site were unveiled at a January 15, 2003, public meeting at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. These were angrily rejected by most of those present, and the design team withdrew from the project. Philadelphia City Council appropriated $1.5 million toward a commemoration of the site, which Mayor John Street announced at the Liberty Bell Center's opening, October 9, 2003.

A second design process was undertaken as a joint project by Independence Park and the City of Philadelphia.[28] Congressmen Chakka Fatah and Robert Brady secured $3.6 million in federal funds for the project, which they jointly announced on September 6, 2005.[29] A national design competition for the President's House site was announced in late 2005, and more than twenty teams of architects, artists and historians submitted proposals. Six of these teams were selected as semi-finalists, and were given stipends to create models and finished drawings. The models and drawings were exhibited at the National Constitution Center and the African American Museum in Summer 2006, and the public had several weeks to comment and cast votes for their favorite design.[18]: 53–54 Philadelphia architectural firm Kelly-Maello was announced as the winner of the design competition on February 27, 2007.[30]

2007 archaeology

[edit]

A second archaeological excavation was begun on March 27, 2007.[31] This was focused on the house's backbuildings, and a temporary observation platform was erected atop the footprint of the main house.

Early discoveries included brick foundations of the three Burt stores, built between the exterior walls of the gutted house. Excavation of the kitchen established that it had a basement, and a section of this had a root cellar below it.[32] At the juncture of the kitchen's foundations and the stores' was found an 1833 coin, possibly left by the builders to mark their completed work.[33] As the stores' plaster cellar floors were chipped away, older foundations were revealed beneath them.

The excavation uncovered the rear wall of the main house and, most surprisingly, much of the curved foundation of Washington's bow window.[34] This two-story semi-circular expansion of the State Dining Room (and the State Drawing Room above it) was designed by the President to be a ceremonial space in which he would receive guests. "There can be little doubt that in Washington's bow can be found the seed that was later to flower in the oval shape of the Blue Room [of the White House]."[35]

Hundreds of thousands of people visited the observation platform between March and July 2007.[18] As the excavation's closing approached, the City and Independence Park issued a joint press release:

More than a quarter million visitors have stood at the public viewing platform to witness this extraordinary place, to learn from the archaeologists, and to interact with each other on important topics such as race relations in the United States. The reaction to the site has served as a signal that the President's House site has the potential to become a major national icon in the heart of the City.[36]

The excavation was closed with a July 31 ceremony that included speeches, the dedication of a bronze plaque listing the names of the nine enslaved held at the site, a prayer, and the African ritual of spilling of sand and water as oblations.[37]

President's House Memorial

[edit]Completed in 2010, the memorial, President's House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation, is an open-air pavilion that shows the outline of the original buildings and allows visitors to view the remaining foundations. Some artifacts are displayed within the pavilion. Signage and video exhibits portray the history of the structure, as well as the roles of Washington's slaves in his household and slaves in American society.[28] The memorial was a joint project of the City of Philadelphia and the National Park Service.[38][39]

-

Memorial at the site of the former President's House.

-

President's House Memorial, looking north.

-

Kitchen foundations

See also

[edit]- Samuel Osgood House, first Presidential mansion

- Alexander Macomb House, second Presidential mansion

- Germantown White House, twice temporarily occupied by President Washington

- White House/Executive Residence, the Washington D.C. home of U.S. presidents and their families

- President's House, house intended for the president on Ninth Street, Philadelphia

- List of residences of presidents of the United States

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Edward Lawler, Jr., "A Brief History of the President's House in Philadelphia", US History, updated May 2010

- ^ a b c Edward Lawler, Jr., "The President's House Revisited", The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, October 2005, pp. 371–410.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Edward Lawler, Jr., "The President's House in Philadelphia: The Rediscovery of a Lost Landmark", The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, January 2002, pp. 5–95.

- ^ Brown, Weldon A. (1941). Empire or independence; a study in the failure of reconciliation, 1774–1783. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press (published 1966). OCLC 341868.

- ^ Philadelphia Deed Book AM-25, p. 202, April 12, 1832.

- ^ The Golden Book of the Wanamaker Stores (Philadelphia, 1911).

- ^ Biographical sketches of the President's House enslaved from ushistory.org

- ^ Edward Lawler, Jr. "President's House Slavery: By the Numbers," from ushistory.org.

- ^ Oney Judge from George Washington's Mount Vernon

- ^ Stephan Salisbury, "A Slave's Defiance: The story of rebellious Oney Judge is finally being told, along with those of other slaves who lived with George and Martha Washington in Philadelphia," The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c Hercules from ushistory.org

- ^ Craig LaBan, "A birthday shock from Washington's chef", The Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 February 2010, accessed 2 April 2012

- ^ Martha Washington to Col. Richard Varick, 15 December 1801. "Worthy Partner:" The Papers of Martha Washington, Joseph E. Fields, ed., (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994), pp. 398–99.

- ^ a b Liana Teixeira, "Centuries-old Mystery Solved by Westport Historical Society," Associated Press, May 16, 2019.

- ^ Hercules from George Washington's Mount Vernon.

- ^ Rodolphe el-Khoury, ed., Liberty Bell Center, Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, (Philadelphia, PA and San Rafael, CA: ORO Editions, 2006), p. 107.

- ^ Faye Flam, "Formerly on Ice, Past Unearthed. The Icehouse Found in Philadelphia Gives a Glimpse into Colonial History," The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 23, 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rebecca Yamin, Digging in the City of Brotherly Love: Stories from Philadelphia Archeology, Yale University Press, 2008.

- ^ The First Icehouse in America? from ushistory.org.

- ^ Robert Morris to George Washington, June 15, 1784, George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c Stephan Salisbury and Inga Saffron, "Echos of Slavery at Liberty Bell Site," The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 24, 2002.

- ^ "A President and His Property," WHYY-FM, December 15, 2010.

- ^ Martha Aikens, Op-ed: "Park Tells the Story of Slavery," The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 7, 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f Gary Nash, "For Whom Will the Liberty Bell Toll: From Controversy to Collaboration," January 25, 2003 lecture given at Christ Church, Philadelphia.

- ^ Avenging The Ancestors http://www.avengingtheancestors.com/index.asp Archived 2017-09-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dwight Pitcaithley to Martha Aikens, April 2002, quoted in Gary Nash, "For Whom Will the Liberty Bell Toll? From Controversy to Collaboration," (January 2003).

- ^ PA House Resolution 490, March 26, 2002 from ushistory.org

- ^ a b "President's House Opens on Independence Mall in Philadelphia", Press Release, City of Philadelphia and Independence National Historical Park, accessed 16 February 2012

- ^ $3.6 million Awarded to the Project from ushistory.org

- ^ Press release: "Finalist Team for President's House Site Selected," City of Philadelphia & INHP, February 27, 2007 (PDF)

- ^ Press release: President's House Archaeological Dig, City of Philadelphia & INHP, March 27, 2007 from ushistory.org

- ^ Archaeology at the President's House: May 1, 2007 from ushistory.org

- ^ Archaeology at the President's House: April 26, 2007 from ushistory.org

- ^ Archaeology at the President's House: May 8, 2007 from ushistory.org

- ^ William Seale, The President's House, A History (Washington, D. C.: White House Historical Association, 1986), p. 8.

- ^ Archaeology at the President's House from ushistory.org

- ^ Archaeology Closing Ceremony at the President's House: July 31, 2007 from ushistory.org

- ^ Stephan Salisbury (August 20, 2012). "Problems still plague Philadelphia's President's House memorial". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on September 18, 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ "The Presidents House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation". City of Philadelphia. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

External links

[edit]- National Park Service: History of the President's House

- "President's House in Philadelphia", from ushistory.org

- Edward Lawler, Jr., "A Brief History of the President's House in Philadelphia", US History, updated May 2010

- "President's House Opens on Independence Mall in Philadelphia", Press Release, City of Philadelphia and Independence National Historical Park

- "Mansion originally belonging to Richard Penn", Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- Houses in Philadelphia

- Buildings and structures in Independence National Historical Park

- Market Street (Philadelphia)

- Old City, Philadelphia

- Presidential residences in the United States

- Presidency of George Washington

- Presidency of John Adams

- Washington family residences

- Demolished buildings and structures in Philadelphia

- Demolished hotels in the United States

- Demolished buildings and structures in Pennsylvania

- Houses completed in 1767

- 1767 establishments in Pennsylvania

- 1832 disestablishments in Pennsylvania

- Monuments and memorials in Philadelphia

- Georgian architecture in Pennsylvania

- Slave cabins and quarters in the United States

- Presidential homes in the United States

- Buildings and structures destroyed in 1832

- Penn family

- Homes of United States Founding Fathers

- Official residences in the United States