Ralph de Luffa

Ralph de Luffa | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Chichester | |

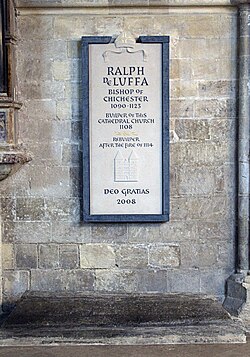

Memorial within Chichester Cathedral | |

| Appointed | before 6 January 1091 |

| Term ended | 14 December 1123 |

| Predecessor | Godfrey |

| Successor | Seffrid |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 6 January 1091 by Thomas of Bayeux |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 14 December 1123 |

Ralph de Luffa (or Ralph Luffa[a] (died 1123) was an English bishop of Chichester, from 1091 to 1123. He built extensively on his cathedral as well as being praised by contemporary writers as an exemplary bishop. He took little part in the Investiture Crisis which took place in England during his episcopate. Although at one point he refused to allow his diocese to be taxed by King Henry I of England, Luffa remained on good terms with the two kings of England he served.

Bishop

[edit]Luffa was consecrated on 6 January 1091[1] by Thomas, the Archbishop of York.[2] Luffa had previously been a chaplain for King William II of England, nicknamed "Rufus", and was also the king's friend.[3] This information comes from the medieval writer Orderic Vitalis, but there is no other confirmation that he was a royal servant.[4] He also served Rufus as a judge, and the historian Norman Cantor calls him a justiciar for Rufus,[5] but the historian Francis West, who studied the justiciar's office, notes that his one of appearance as a royal judge concerns his diocese, and that Luffa probably was mentioned only because he was expected to enforce the decision.[6]

During the crisis between the king and Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury in 1095 and 1096, Luffa managed to support Anselm while retaining the king's respect.[3][7] Under King Henry I, William's younger brother and successor, Luffa took little part in the Investiture Crisis in England. In 1106, Luffa did sign a letter to Anselm written by William Giffard Bishop of Winchester-elect that begged the archbishop to return to England from his exile.[8]

Luffa gained King Henry's respect because Luffa was the lone bishop to resist Henry's financial extortion from the clergy.[9] As part of this dispute, Luffa ordered that all church services be discontinued and the church doors in his diocese be blocked with thorns.[10] It was during Luffa's tenure of the see that the first disputes between the bishop and Battle Abbey started, although they were not large. During Luffa's episcopate, he and the abbey disputed over the right of the bishop to be entertained by the abbey and the requirement that the abbot attend the diocesan councils.[9] The dispute only reached its climax during the episcopate of Hilary of Chichester, who was Bishop of Chichester from 1147 to 1169.[11] Luffa also supported Anselm's attempts to assert Canterbury's primacy over the Archbishop of York in 1108 and 1109.[9]

William of Malmesbury had high praise for Luffa's actions as bishop, where he is said to have toured his diocese three times a year on preaching tours. He also allowed only freely given gifts from his flock, avoiding all appearance of extorting donations.[3] He was also praised by contemporaries for his diligence is seeking worthy candidates for the priesthood.[12] William of Malmesbury also praised Luffa's piety.[13]

Cathedral builder

[edit]

Traditionally Luffa is held to have begun the building of Chichester Cathedral, the eastern section of which was dedicated in 1108.[14] However, this view has been challenged by the art historian R. D. H. Gem, who argues that because of the conservative nature of the architecture it was more probably begun under Luffa's predecessor, Stigand, who was bishop from 1070 to 1087, and who oversaw the transfer of the seat of the bishopric from Selsey to Chichester.[15] Most historians still incline to the belief that Luffa began the cathedral construction, however.[9][16][17]

After his cathedral church was burned down in 1114, Luffa managed to secure King Henry I's financial help in rebuilding the church.[9] Besides the rebuilding, Luffa built a Lady chapel, which still remains. Other work still extant in the cathedral are the arcades, the exteriors of the clerestory and those galleries that are unvaulted.[16] The art historian George Zarnecki has argued that the rood screen in the cathedral also dates from Luffa's episcopate. Two panels from this work still survive, and depict the meeting of Jesus with Mary and Martha at Bethany as well as the miracle where Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead. The scenes show some resemblance to works in Hildesheim and Cologne, and this resemblance may mean that Luffa was from Germany, or hired sculptors from there.[18]

Death and legacy

[edit]On Luffa's deathbed, he gave away all his belongings, including his sheets and underclothes.[3] He died on 14 December 1123.[1] Contemporary records report that he had a great awareness of his responsibilities as a bishop.[19] Six documents of Luffa's survive, besides his profession of obedience.[20]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The first name is sometimes spelled Ralf.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 238

- ^ Greenway "Bishops" Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 5: Chichester

- ^ a b c d Barlow English Church p. 68

- ^ Brett English Church p. 111 footnote 1

- ^ Cantor Church, Kingship and Lay Investiture p. 33 footnote 102

- ^ West Justiciarship pp. 11–12

- ^ Cantor Church, Kingship and Lay Investiture p. 81

- ^ Cantor Church, Kingship and Lay Investiture p. 256

- ^ a b c d e Mayr-Harting "Ralph (Ralph Luffa)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings p. 448

- ^ Knowles Monastic Order p. 589

- ^ Brett English Church pp. 119–120

- ^ Barlow William Rufus p. 180

- ^ Kerr and Kerr Guide to Norman Sites pp. 37–38

- ^ Gem "Chichester Cathedral" Proceedings of the Battle Conference III pp. 61–64

- ^ a b Wischermann "Romanesque Architecture" Romanesque p. 235

- ^ Dodwell Anglo-Saxon Art p. 233

- ^ Geese "Romanesque Sculpture" Romanesque pp. 320–321

- ^ Mayr-Harting "Introduction" Acta p. 5

- ^ Mayr-Harting "Introduction" Acta p. 26

References

[edit]- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1066–1154: A History of the Anglo-Norman Church. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- Barlow, Frank (1983). William Rufus. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04936-5.

- Bartlett, Robert C. (2000). England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings: 1075–1225. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822741-8.

- Brett, M. (1975). The English Church under Henry I. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821861-3.

- Cantor, Norman F. (1958). Church, Kingship, and Lay Investiture in England 1089–1135. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 186158828.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1985). Anglo-Saxon Art: A New Perspective. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9300-5.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Geese, Uwe (2007). "Romanesque Sculpture". In Toman, Rolf (ed.). Romanesque: Architecture Sculpture Painting. Köln: Könemann. pp. 256–323. ISBN 978-3-8331-3600-9.

- Gem, R. D. H. (1981). "Chichester Cathedral: When was the Romanesque Church Begun". In Brown, R. Allen (ed.). Proceedings of the Battle Conference on Anglo-Norman Studies Volume III 1980. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 61–64. ISBN 0-85115-142-6.

- Greenway, Diana E. (1996). "Bishops". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300. Vol. 5: Chichester. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- Kerr, Mary; Kerr, Nigel (1984). A Guide to Norman Sites in Britain. London: Granada. ISBN 0-246-11976-4.

- Knowles, David (1976). The Monastic Order in England: A History of its Development from the Times of St. Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council, 940–1216 (Second reprint ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05479-6.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1964). "Introduction". The Acta of the Bishops of Chichester 1075–1207. Torquay, UK: Canterbury & York Society. pp. 3–70. OCLC 3812576.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (2004). "Ralph (Ralph Luffa) (d. 1123)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23049. Retrieved 24 November 2007. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- West, Francis (1966). The Justiciarship in England 1066–1232. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 953249.

- Wischermann, Heinfried (2007). "Romanesque Architecture in Great Britain". In Toman, Rolf (ed.). Romanesque: Architecture Sculpture Painting. Köln: Könemann. pp. 216–255. ISBN 978-3-8331-3600-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Searle, Eleanor (July 1968). "Battle Abbey and Exemption: The Forged Charters". The English Historical Review. 83 (328): 449–480. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXIII.CCCXXVIII.449. JSTOR 564160.