Road traffic safety

Road traffic safety refers to methods and measures for reducing the risk of a person using the road network for being killed or seriously injured. The users of a road include pedestrians, cyclists, motorists, their passengers, and passengers of on-road public transport, mainly buses and trams. Best-practice road safety strategies focus upon the prevention of serious injury and death crashes in spite of human fallibility[1] (which is contrasted with the old road safety paradigm of simply reducing crashes assuming road user compliance with traffic regulations). Safe road design is now about providing a road environment which ensures vehicle speeds will be within the human tolerances for serious injury and death wherever conflict points exist.

The basic strategy of a Safe System approach is to ensure that in the event of a crash, the impact energies remain below the threshold likely to produce either death or serious injury. This threshold will vary from crash scenario to crash scenario, depending upon the level of protection offered to the road users involved. For example, the chances of survival for an unprotected pedestrian hit by a vehicle diminish rapidly at speeds greater than 30 km/h, whereas for a properly restrained motor vehicle occupant the critical impact speed is 50 km/h (for side impact crashes) and 70 km/h (for head-on crashes).

— International Transport Forum, Towards Zero, Ambitious Road Safety Targets and the Safe System Approach, Executive Summary page 19[1]

As sustainable solutions for all classes of road have not been identified, particularly lowly trafficked rural and remote roads, a hierarchy of control should be applied, similar to best practice Occupational Safety and Health. At the highest level is sustainable prevention of serious injury and death crashes, with sustainable requiring all key result areas to be considered. At the second level is real time risk reduction, which involves providing users at severe risk with a specific warning to enable them to take mitigating action. The third level is about reducing the crash risk which involves applying the road design standards and guidelines (such as from AASHTO), improving driver behaviour and enforcement.[1]

Background

Road traffic crashes are one of the world’s largest public health and injury prevention problems. The problem is all the more acute because the victims are overwhelmingly healthy before their crashes. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 1 million people are killed on the world’s roads each year.[2] A report published by the WHO in 2004 estimated that some 1.2 million people were killed and 50 million injured in traffic collisions on the roads around the world each year[3] and was the leading cause of death among children 10–19 years of age. The report also noted that the problem was most severe in developing countries and that simple prevention measures could halve the number of deaths.[4]

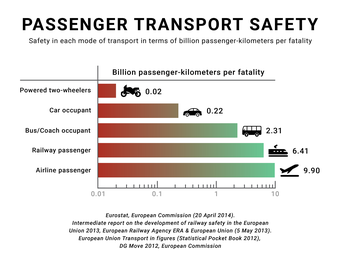

The standard measures used in assessing road safety interventions are fatalities and killed or seriously injured (KSI) rates, usually per billion (109) passenger kilometres. Countries caught in the old road safety paradigm,[5] replace KSI rates with crash rates — for example, crashes per million vehicle miles.

Vehicle speed within the human tolerances for serious injury and death is a key goal of modern road design because impact speed affects the severity of injury to both occupants and pedestrians. For occupants, Joksch (1993) found the probability of death for drivers in multi-vehicle accidents increased as the fourth power of impact speed (often referred to by the mathematical term δv ("delta V"), meaning change in velocity). Injuries are caused by sudden, severe acceleration (or deceleration); this is difficult to measure. However, crash reconstruction techniques can estimate vehicle speeds before a crash. Therefore, the change in speed is used as a surrogate for acceleration. This enabled the Swedish Road Administration to identify the KSI risk curves using actual crash reconstruction data which led to the human tolerances for serious injury and death referenced above.

Interventions are generally much easier to identify in the modern road safety paradigm, whose focus is on the human tolerances for serious injury and death. For example, the elimination of head-on KSI crashes simply required the installation of an appropriate median crash barrier. For example, roundabouts, with speed reducing approaches, encounter very few KSI crashes.

The old road safety paradigm of purely crash risk is a far more complex matter. Contributing factors to highway crashes may be related to the driver (such as driver error, illness or fatigue), the vehicle (brake, steering, or throttle failures) or the road itself (lack of sight distance, poor roadside clear zones, etc.). Interventions may seek to reduce or compensate for these factors, or reduce the severity of crashes. A comprehensive outline of interventions areas can be seen in management systems for road safety.

In addition to management systems, which apply predominantly to networks in built-up areas, another class of interventions relates to the design of roadway networks for new districts. Such interventions explore the configurations of a network that will inherently reduce the probability of collisions.[6]

Interventions for the prevention of road traffic injuries are often evaluated; the Cochrane Library has published a wide variety of reviews of interventions for the prevention of road traffic injuries.[7][8]

For road traffic safety purposes it can be helpful to classify roads into three usages: built-up urban streets with slower speeds, dense and diverse road users; non built-up rural roads with higher speeds; and major highways (motorways/ Interstates/ freeways/ Autobahns, etc.) reserved for motor-vehicles and designed to minimize and attenuate crashes. Most casualties occur on urban streets but most fatalities on rural roads, while motorways are the safest in relation to distance traveled. For example, in 2013, German autobahns carried 31% of motorized road traffic (in travel-kilometres) while accounting for 13% of Germany's traffic deaths. The autobahn fatality rate of 1.9 deaths per billion-travel-kilometres compared favorably with the 4.7 rate on urban streets and 6.6 rate on rural roads.[9]

| Road Class | Injury Crashes | Fatalities | Injury Rate[rate 1] | Fatality Rate[rate 1] | Fatalities per 1000 Injury Crashes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autobahn | 18,452 | 428 | 82 | 1.9 | 23.2 |

| Rural | 73,003 | 1,934 | 249 | 6.6 | 26.5 |

| Urban | 199,650 | 977 | 958 | 4.7 | 4.9 |

| Total, Average | 291,105 | 3,399 | 401 | 4.6 | 11.6 |

Built-up areas

On neighborhood roads where many vulnerable road users, such as pedestrians and bicyclists can be found, traffic calming can be a tool for road safety. Though not strictly a traffic calming measure, mini-traffic circles implanted in normal intersections of neighbourhood streets have been shown to reduce collisions at intersections dramatically[10] (see picture). Shared space schemes, which rely on human instincts and interactions, such as eye contact, for their effectiveness, and are characterised by the removal of traditional traffic signals and signs, and even by the removal of the distinction between carriageway (roadway) and footway (sidewalk), are also becoming increasingly popular. Both approaches can be shown to be effective.

For planned neighbourhoods, studies recommend new network configurations, such as the Fused Grid or 3-Way Offset. These layout models organize a neighbourhood area as a zone of no cut-through traffic by means of loops or dead-end streets. They also ensure that pedestrians and bicycles have a distinct advantage by introducing exclusive shortcuts by path connections through blocks and parks. Such a principle of organization is referred to as "Filtered Permeability" implying a preferential treatment of active modes of transport. These new patterns, which are recommended for laying out neighbourhoods, are based on analyses of collision data of large regional districts and over extended periods.[11][12][13] They show that four-way intersections combined with cut-through traffic are the most significant contributors to increased collisions.

Modern safety barriers are designed to absorb impact energy and minimize the risk to the occupants of cars and bystanders. For example, most side rails are now anchored to the ground, so that they cannot skewer a passenger compartment. Most light poles are designed to break at the base rather than violently stop a car that hits them. Some road fixtures such as signs and fire hydrants are designed to collapse on impact. Highway authorities have removed trees in the vicinity of roads; while the idea of "dangerous trees" has attracted a certain amount of skepticism, unforgiving objects such as trees can cause severe damage and injury to errant road users.

Most roads are cambered (crowned), that is, made so that they have rounded surfaces, to reduce standing water and ice, primarily to prevent frost damage but also increasing traction in poor weather. Some sections of road are now surfaced with porous bitumen to enhance drainage; this is particularly done on bends. These are just a few elements of highway engineering. As well as that, there are often grooves cut into the surface of cement highways to channel water away, and rumble strips at the edges of highways to rouse inattentive drivers with the loud noise they make when driven over. In some cases, there are raised markers between lanes to reinforce the lane boundaries; these are often reflective. In pedestrian areas, speed bumps are often placed to slow cars, preventing them from going too fast near pedestrians.

Poor road surfaces can lead to safety problems. If too much asphalt or bitumenous binder is used in asphalt concrete, the binder can 'bleed' or flush' to the surface, leaving a very smooth surface that provides little traction when wet. Certain kinds of stone aggregate become very smooth or polished under the constant wearing action of vehicle tyres, again leading to poor wet-weather traction. Either of these problems can increase wet-weather crashes by increasing braking distances or contributing to loss of control. If the pavement is insufficiently sloped or poorly drained, standing water on the surface can also lead to wet-weather crashes due to hydroplaning.

Lane markers in some countries and states are marked with cat's eyes, Botts' dots or reflective raised pavement markers that do not fade like paint. Botts dots are not used where it is icy in the winter, because frost and snowplows can break the glue that holds them to the road, although they can be embedded in short, shallow trenches carved in the roadway, as is done in the mountainous regions of California.

Road hazards and intersections in some areas are now usually marked several times, roughly five, twenty, and sixty seconds in advance so that drivers are less likely to attempt violent manoeuvres.

Most road signs and pavement marking materials are retro-reflective, incorporating small glass spheres[14] or prisms to more efficiently reflect light from vehicle headlights back to the driver's eyes.

Turning across traffic

Turning across traffic (i.e., turning left in right-hand drive countries, turning right in left-hand drive countries) poses several risks. The more serious risk is a collision with oncoming traffic. Since this is nearly a head-on collision, injuries are common. It is the most common cause of fatalities in a built-up area. The other risk is involvement in a rear-end collision while waiting for a gap in oncoming traffic.

Countermeasures for this type of collision include:

- Addition of left turn lanes[15]

- Providing protected turn phasing at signalized intersections[16]

- Using indirect turn treatments such as the Michigan left

- Converting conventional intersections to roundabouts[15]

In the absence of these facilities as a driver about to turn:

- Keep your wheels straight, so that in the event of a rear end shunt, you are not pushed into on-coming traffic.

- When you think it is clear, look away, to the road that you are entering. There is an optical illusion that, after a time, presents an oncoming vehicle as further away and travelling slower. Looking away breaks this illusion.

There is no presumption of negligence which arises from the bare fact of a collision at an intersection,[17] and circumstances may dictate that a left turn is safer than to turn right. The American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) recommends in their publication Geometric Design of Highways and Streets[18] that left or right turns are to be provided the same time gap.[19] Some states have recognized this in statute, and a presumption of negligence is only raised because of the turn if and only if the turn was prohibited by an erected sign.[20]

Turns across traffic have been shown to be problematic for older drivers.[21]

Designing for pedestrians and cyclists

Pedestrians and cyclists are among the most vulnerable road users[22] and in some countries constitute over half of all road deaths. Interventions aimed at improving safety of non-motorised users:

- Sidewalks of suitable width for pedestrian traffic

- Pedestrian crossings close to the desire line which allow pedestrians to cross roads safely

- Segregated pedestrian routes and cycle lanes away from the main highway

- Overbridges (tend to be unpopular with pedestrians and cyclists due to additional distance and effort)

- Underpasses (these can pose heightened risk from crime is not designed well, can work for cyclists in some cases)

- Traffic calming and speed humps

- Low speed limits that are rigorously enforced, possibly by speed cameras

- Shared space schemes giving ownership of the road space and equal priority to all road users, regardless of mode of use

- Pedestrian barriers to prevent pedestrians crossing dangerous locations

Pedestrians' advocates question the equitability of schemes if they impose extra time and effort on the pedestrian to remain safe from vehicles, for example overbridges with long slopes or steps up and down, underpasses with steps and addition possible risk of crime and at-grade crossings off the desire line. Make Roads Safe was criticised in 2007 for proposing such features. Successful pedestrian schemes tend to avoid over-bridges and underpasses and instead use at-grade crossings (such as pedestrian crossings) close to the intended route. Successful cycling scheme by contrast avoid frequent stops even if some additional distance is involved given that the main effort required for cyclists is starting off.

In Costa Rica 57% of road deaths are pedestrians. However, a partnership between AACR, Cosevi, MOPT and iRAP has proposed the construction of 190 km of pedestrian footpaths and 170 pedestrian crossings which could save over 9000 fatal or serious injuries over 20 years.[23]

Shared space

By 1947 the Pedestrians' Association was suggesting that many of the safety features being introduced (speed limits, traffic calming, road signs and road markings, traffic lights, Belisha beacons, pedestrian crossings, cycle lanes, etc.) were potentially self-defeating because "every nonrestrictive safety measure, however admirable in itself, is treated by the drivers as an opportunity for more speeding, so that the net amount of danger is increased and the latter state is worse than the first."[24]

During the 1990s a new approach, known as 'shared space' was developed which removed many of these features in some places has attracted the attention of authorities around the world.[25][26] The approach was developed by Hans Monderman who believed that "if you treat drivers like idiots, they act as idiots"[27] and proposed that trusting drivers to behave was more successful than forcing them to behave.[28] Professor John Adams, an expert on risk compensation suggested that traditional traffic engineering measures assumed that motorists were "selfish, stupid, obedient automatons who had to be protected from their own stupidity" and non-motorists were treated as "vulnerable, stupid, obedient automatons who had to be protected from cars – and their own stupidity".[29]

Reported results indicate that the 'shared space' approach leads to significantly reduced traffic speeds, the virtual elimination of road casualties, and a reduction in congestion.[28] Living streets share some similarities with shared spaces. The woonerven also sought to reduce traffic speeds in community and housing zones by the use of lower speed limits enforced by the use of special signage and road markings, the introduction of traffic calming measures, and by giving pedestrians priority over motorists.

Non built-up areas

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2010) |

Major highways

Major highways including motorways, freeways, Autobahnen and interstates are designed for safer high-speed operation and generally have lower levels of injury per vehicle km than other roads; for example, in 2013, the German autobahn fatality rate of 1.9 deaths per billion-travel-kilometers compared favorably with the 4.7 rate on urban streets and 6.6 rate on rural roads.[9]

Safety features include:

- limited access from properties and local roads.

- Grade separated junctions

- Median dividers between opposite-direction traffic to reduce likelihood of head-on collisions

- Removing roadside obstacles.

- Prohibition of more vulnerable road users and slower vehicles.

- Placements of energy attenuation devices (e.g. guard rails, wide grassy areas, sand barrels).

- Eliminating road toll booths

The ends of some guard rails on high-speed highways in the United States are protected with impact attenuators, designed to gradually absorb the kinetic energy of a vehicle and slow it more gently before it can strike the end of the guard rail head on, which would be devastating at high speed. Several mechanisms are used to dissipate kinetic energy. Fitch Barriers, a system of sand-filled barrels, uses momentum transfer from the vehicle to the sand. Many other systems tear or deform steel members to absorb energy and gradually stop the vehicle.

In some countries major roads have "tone bands" impressed or cut into the edges of the legal roadway, so that drowsing drivers are awakened by a loud hum as they release the steering and drift off the edge of the road. Tone bands are also referred to as "rumble strips", owing to the sound they create. An alternative method is the use of "Raised Rib" markings, which consists of a continuous line marking with ribs across the line at regular intervals. They were first specially authorised for use on motorways as an edge line marking to separate the edge of the hard shoulder from the main carriageway. The objective of the marking is to achieve improved visual delineation of the carriageway edge in wet conditions at night. It also provides an audible/vibratory warning to vehicle drivers, should they stray from the carriageway, and run onto the marking.

Better motorways are banked on curves to reduce the need for tire-traction and increase stability for vehicles with high centers of gravity.

An example of the importance of roadside clear zones can be found on the Isle of Man TT motorcycle race course. It is much more dangerous than Silverstone because of the lack of runoff. When a rider falls off at Silverstone, he slides along slowly losing energy, with minimal injuries. When he falls off in the Manx, he impacts violently with trees and walls. Similarly, a clear zone alongside a freeway or other high speed road can prevent off-road excursions from becoming fixed-object crashes.

The US has developed a prototype automated roadway, to reduce driver fatigue and increase the carrying capacity of the roadway. Roadside units participating in future Wireless vehicle safety communications networks have been studied.

Motorways are far more expensive and space-consumptive to build than ordinary roads, so are only used as principal arterial routes. In developed nations, motorways bear a significant portion of motorized travel; for example, the United Kingdom's 3533 km of motorways represented less than 1.5% of the United Kingdom's roadways in 2003, but carry 23% of road traffic.

The proportion of traffic borne by motorways is a significant safety factor. For example, even though the United Kingdom had a higher fatality rates on both motorways and non-motorways than Finland, both nations shared the same overall fatality rate in 2003. This result was due to the United Kingdom's higher proportion of motorway travel.

Similarly, the reduction of conflicts with other vehicles on motorways results in smoother traffic flow, reduced collision rates, and reduced fuel consumption compared with stop-and-go traffic on other roadways.

The improved safety and fuel economy of motorways are common justifications for building more motorways. However, the planned capacity of motorways is often exceeded in a shorter timeframe than initially planned, due to the under estimation of the extent of the suppressed demand for road travel. In developing nations, there is significant public debate on the desirability of continued investment in motorways.

With effect from January 2005 and based primarily on safety grounds, the UK’s Highways Agency's policy is that all new motorway schemes are to use high containment concrete step barriers in the central reserve. All existing motorways will introduce concrete barriers into the central reserve as part of ongoing upgrades and through replacement as and when these systems have reached the end of their useful life. This change of policy applies only to barriers in the central reserve of high speed roads and not to verge side barriers. Other routes will continue to use steel barriers.

More people die on the hard shoulder than on the highway itself. Without other vehicles passing a parked car, following drivers are unaware that the vehicle is parked, despite hazard lights. Truck drivers indicate that they are parked by putting their cab seat behind their truck. In the UK, the AA and police park their vehicles on the hard shoulder at a slight angle so that following drivers can see down the side of their vehicle and are therefore aware that they are stopped.

30% of highway crashes that occur in the vicinity of toll collection booths in the countries that have them, these can be reduced by switching to electronic toll systems.[30]

Vehicle safety

Safety can be improved in various ways depending on the transport taken.

Buses and coaches

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Safety can be improved in various simple ways to reduce the chance of an accident occurring. Avoiding rushing or standing in unsafe places on the bus or coach and following the rules on the bus or coach itself will greatly increase the safety of a person travelling by bus or coach. Various safety features can also be implemented into buses and coaches to improve safety including safety bars for people to hold onto.

The main ways to stay safe when travelling by bus or coach are as follows:

- Leave your location early so that you do not have to run to catch the bus or coach.

- At the bus stop, always follow the queue.

- Do not board or alight at a bus stop other than an official one.

- Never board or alight at a red light crossing or unauthorized bus stop.

- Board the bus only after it has come to a halt without rushing in or pushing others.

- Do not sit, stand or travel on the footboard of the bus.

- Do not put any part of your body outside a moving or a stationary bus.

- While in the bus, refrain from shouting or making noise as it can distract the driver.

- Always hold onto the handrail if standing in a moving bus, especially on sharp turns.

- Always adhere to the bus safety rules.

Cars

Safety can be improved by reducing the chances of a driver making an error, or by designing vehicles to reduce the severity of crashes that do occur. Most industrialized countries have comprehensive requirements and specifications for safety-related vehicle devices, systems, design, and construction. These may include:

- Passenger restraints such as seat belts — often in conjunction with laws requiring their use — and airbags

- Crash avoidance equipment such as lights and reflectors

- Driver assistance systems such as Electronic Stability Control

- Crash survivability design including fire-retardant interior materials, standards for fuel system integrity, and the use of safety glass

- Sobriety detectors: These interlocks prevent the ignition key from working if the driver breathes into one and it detects significant quantities of alcohol. They have been used by some commercial transport companies, or suggested for use with persistent drunk-driving offenders on a voluntary basis[31]

Motorbikes

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2010) |

According to statistics, the percentage of intoxicated motorcyclists in fatal crashes is higher than other riders on roads.[32] Helmets also play a major role in the safety of motorcyclists. In 2008, The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimated the helmets are 37 percent effective in saving lives of motorcyclists involved in crashes.[33]

Trucks

According to the European Commission Transportation Department "it has been estimated that up to 25% of accidents involving trucks can be attributable to inadequate cargo securing".[34] Improperly secured cargo can cause severe accidents and lead to loss of cargo, loss of lives, loss of vehicles and can be a hazard for the environment. One way to stabilize, secure and protect cargo during transportation on the road is by using Dunnage Bags which are placed in the void between the cargo and are designed to prevent the load from moving during transport.

Regulation of road users

Various types of road user regulations are in force or have been tried in most jurisdictions around the world, some these are discussed by road user type below.

Motor vehicle users

Dependent on jurisdiction, driver age, road type and vehicle type, motor vehicle drivers may be required to pass a driving test (public transport and goods vehicle drivers may need additional training and licensing), conform to restrictions on driving after consuming alcohol or various drugs, comply with restrictions on use of mobile phones, be covered by compulsory insurance, wear seat belts and comply with certain speed limits. Motorcycle riders may additionally be compelled to wear a motorcycle helmet. Drivers of certain vehicle types may be subject to maximum driving hour regulations.

Some jurisdictions such as the US states Virginia and Maryland, have implemented specific regulations such as the prohibiting mobile phone use by, and limiting the number of passengers accompanying, young and inexperienced drivers.[35] It has been noticed that more serious collisions occur at night, when the car has multiple occupants, and when seat belt use is less.[36]

Insurance companies[which?] have proposed[where?] that the following restrictions should be imposed on new drivers:[citation needed] a "curfew" imposed on young drivers to prevent them driving at night, an experienced supervisor to chaperone the less experienced driver, forbidding the carrying of passengers, zero alcohol tolerance, raising the standards required for driving instructors and improving the driving test, vehicle restrictions (e.g. restricting access to 'high-performance' vehicles), a sign placed on the back of the vehicle (an N- or P-Plate) to notify other drivers of a novice driver and encouraging good behaviour in the post-test period.

Some countries or states have already implemented some of these ideas.[citation needed] Pay-as-you-drive adjusts insurance costs according to when and where the person drives.

Pedal bicycle users

Dependent on jurisdiction, road type and age, pedal cyclists may be required conform to restrictions on driving after consuming alcohol or various drugs, comply with restrictions on use of mobile phones, be covered by compulsory insurance, wear a bicycle helmet and comply with certain speed limits.

Pedestrians

Dependent on jurisdiction, jaywalking may be prohibited.

Animals

Collisions with animals are usually fatal to the animals, and occasionally to drivers as well.

Information campaigns

Information campaigns can be used to raise awareness of initiatives designed to reduce road casualty levels. Examples include:

- Decade of Action by World Health Organization and Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (2011-2020)

- traffic awareness campaigns such as the "one false move" campaign documented by Hillman et al.

- Speeding. No one thinks big of you. (New South Wales, Australia, 2007)

- Road Safety is no Accident World Health Organization

- Designated driver campaign, (US, 1970s-present)

- Click It or Ticket, (US, 1993–present)

- Clunk Click Every Trip (UK 1971)

- Green Cross Code (UK 1970–present)

Statistics

Rating roads for safety

Since 1999 the EuroRAP initiative has been assessing major roads in Europe with a road protection score. This results in a star rating for roads based on how well its design would protect car occupants from being severely injured or killed if a head-on, run-off, or intersection accident occurs, with 4 stars representing a road with the best survivability features.[39] The scheme states it has highlighted thousands of road sections across Europe where road-users are routinely maimed and killed for want of safety features, sometimes for little more than the cost of safety fencing or the paint required to improve road markings.[40]

There are plans to extend the measurements to rate the probability of an accident for the road. These ratings are being used to inform planning and authorities' targets. For example, in Britain two-thirds of all road deaths in Britain happen on rural roads, which score badly when compared to the high quality motorway network; single carriageways claim 80% of rural deaths and serious injuries, while 40% of rural car occupant casualties are in cars that hit roadside objects, such as trees. Improvements in driver training and safety features for rural roads are hoped to reduce this statistic.[41]

The number of designated traffic officers in the UK fell from 15–20% of Police force strength in 1966 to seven per cent of force strength in 1998, and between 1999 and 2004 by 21%.[42] It is an item of debate whether the reduction in traffic accidents per 100 million miles driven over this time[43] has been due to robotic enforcement.

In the United States, roads are not government-rated, for media-releases and public knowledge on their actual safety features. However, in 2011, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's Traffic Safety Facts found that over 800 persons were killed across the USA by "non-fixed objects" that includes roadway debris. California had the highest number of total deaths from those crashes; New Mexico had a best chance for an individual to die from experiencing any vehicle-debris crash.[44]

KSI statistics

According to WHO in 2010 it was estimated that 1.24 million people were killed worldwide and 50 million more were injured in motor vehicle collisions. Young adults aged between 15 and 44 years account for 59% of global road traffic deaths. Other key facts according to the WHO report are:[45]

- Road traffic injuries are the leading cause of death among young people, aged 15–29 years.

- 91% of the world's fatalities on the roads occur in low-income and middle-income countries, even though these countries have approximately half of the world's vehicles.

- Half of those dying on the world’s roads are "vulnerable road users": pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists.

- Without action, road traffic crashes are predicted to result in the deaths of around 1.9 million people annually by 2020.

- Only 28 countries, representing 416 million people (7% of the world’s population), have adequate laws that address all five risk factors (speed, drink-driving, helmets, seat-belts and child restraints).

It is estimated that motor vehicle collisions caused the death of around 60 million people during the 20th century around the same number of World War II casualties.[46]

As the comparatively poor improvements in pedestrian safety have become a concern at OECD level, the Joint Transport Research Centre of OECD and the International Transport Forum (JTRC) convened an international expert group and published a report entitled ”Pedestrian Safety, Urban Space and Health in 2012”.[47]

According to the OECD's International Transport Forum (ITF), in 2013 the key figures among their 37 member states and observer countries looked like the following:[48]

| Country | Deaths per 1 million inhabitants |

Deaths per 10 billion vehicle-km |

Deaths per 100 000 registered vehicles |

Registered vehicles per 1 000 inhabitants | Seatbelt wearing rates Front (driver,passenger)/ Rear (adults,children) | speed limit urban / rural / motorways (km/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 123 | n.a. | 23 | 529 | 52%,45% / 19%,45% | 30-60 / 110 / 130 | |

| 51 | 50 | 7 | 751 | 97% / 96% | 50, 60-80 / 100 or 110 / 110 | |

| 54 | 58 | 8 | 710 | 89% / 77% | 50 / 100 / 130 | |

| 65 | 71 | 10 | 627 | 86% / 63%,79%[Note 1] | 30-50 / 70-90 / 120 | |

| 143[Note 2] | n.a. | 78[Note 2] | 151 | 17% / n.a. | 40 / 90 / n.a. | |

| 55 | 56 | 9 | 644 | 95% / 95% (estimated) | 40-70 / 80-90 / 100-110 | |

| 120 | n.a. | 50 | 237 | 62,78% / 15% | 60 / 100-120 / 120 | |

| 62 | 157 | 11 | 560 | 97% / 66%[Note 1] | 50 / 90 / 130 | |

| 34 | 39 | 6 | 523 | 94% / 81%[Note 1] | 50 / 80 / 130 (110) | |

| 48 | 48 | 7 | 725 | 95% / 87% | 50 / 80 (winter) 100 (summer) / 120 (100) | |

| 51 | 58 | 8 | 647 | 98% / 84%,90%[Note 3] | 50 / 90 / 130 (110 bad w.) | |

| 41 | 46 | 6 | 651 | 96-98% / 97,98% | 50 / 100 / no limit or 130 | |

| 79 | n.a. | 11 | 726 | 77%,74% / 23%[Note 4] | 50 / 90 (110) / 130 (110) | |

| 60 | n.a. | 16 | 366 | 87% / 57%,90% | 50 / 90 / 130 (110) | |

| 47 | 47 | 6 | 830 | 84% / 65% | 50 / 90 (80) / n.a. | |

| 41 | 40 | 8 | 541 | 92% / 88%,91% | 50 / 80 or 100 / 120 | |

| 34 | 54 | 9 | 352 | 97% / 74% | 50,70 / 80,90,100 / 110 | |

| 57 | n.a. | 7 | 821 | 64%-76% / 10%[Note 5] | 50 / 90-110 / 130 (110 bad w., 100 novice, 150) | |

| 122[Note 2] | n.a. | 87 | 130 | 44% / very low (estimated)[Note 6] | 50 / 50 / 70 or 110 | |

| 40 | 69 | 6 | 657 | 96%,94% / 61% | 40,50,60 / 50,60 / 100 | |

| 101 | 172 | 23 | 450 | 89%,75% / 22% (on motorways) | 60 / 60-80 / 110 (100) | |

| 87 | n.a. | 11 | 766 | 95% / 33% | 50 / 90 (70) / 120 or 130 (110 in winter) | |

| 84 | n.a. | 11 | 771 | 80% / n.a.[Note 7] | 50 / 90 / 130 (110 in rain) | |

| 231 | 122 | 29 | 792[Note 8] | 82%,68% / 9% | 50 / 90 / 110 | |

| 116 | n.a. | 117 | 100 | 49%,46% / n.a.[Note 5] | 50 / 100 / 120 | |

| 34 | 45 | 5 | 537 | 97% / 82%[Note 3] | 50 / 80 / 130 | |

| 57 | 63 | 8 | 734 | 97% / 92%,93% | 50 / 100 / 100 | |

| 37 | 43 | 5 | 707 | 95% / 87-88% | 30,50 / 80 / 90,100,110 | |

| 87 | n.a. | 14 | 636 | 90% / 71%,89% | 50 (60) / 90-120 / 140 | |

| 61 | n.a. | 11 | 551 | 96% / 77%,89-100% | 50 / 90 / 120 | |

| 91 | n.a. | 30 | 299 | 70% / 4% | 50 / 80 / 120 | |

| 61 | 72 | 10 | 638 | 94% / 66%,87-94% | 50 / 90 (110) / 130 | |

| 36 | n.a. | 5 | 662 | 90% / 81%[Note 1] | 50 / 90 or 100 / 120 | |

| 27 | 34 | 5 | 597 | 97% / 81%,95% | 30,40,50 / 60,70,80,90,100 / 110 or 120 | |

| 33 | 43 | 5 | 708 | 94%,93% / 77%,93% | 50 / 80 / 120 | |

| 28 | 35 | 5 | 551 | 96% / 92% | 48 / 96 or 113 / 113 | |

| 103 | 68 | 12 | 852 | 87% / 74% | set by state / set by state / 88-129 (set by state) |

Advocacy groups

The Automobile Association was established in 1905 in the United Kingdom to help motorists avoid police speed traps.[49] They became involved in other safety issues and also erected thousands of roadside warning signs.[49]

The Pedestrians Association in the United Kingdom was formed in 1929 to press for better road safety. Other groups have been active in other countries.[citation needed]

The International Road Federation has an issue area and working group dedicated to road safety. They work with their membership to advocate measures that improve road safety through infrastructure and cooperation with other international organizations.[50]

Motoring advocacy groups including the Association of British Drivers (UK), Speed cameras.org[51] (UK), National Motorists Association (USA/Canada) argue that the strict enforcement of speed limits does not necessarily result in safer driving, and may even have negative effect on road safety in general. Safe Speed is a UK group set up specifically to campaign against the use of Speed cameras. The Association of British Drivers also argues that speed humps result in increased air pollution, increased noise pollution, and even unnecessary vehicle damage.[citation needed]

In 1965, Ralph Nader put pressure on car manufactures in his book Unsafe at Any Speed detailing resistance by car manufacturers to the introduction of safety features, like seat belts, and their general reluctance to spend money on improving safety. The GM President James Roche was later forced to appear before a United States Senate subcommittee, and to apologize to Nader for the company's campaign of harassment and intimidation. Nader later successfully sued GM for excessive invasion of privacy.[52]

RoadPeace was formed in 1991 in the United Kingdom to advocate for better road safety and founded World Day of Remembrance for Road Traffic Victims in 1993 which received support from the United Nations General Assembly in 2005.[53][54]

There is some controversy over the way that the motor advocacy groups has been seen to dominate the road safety agenda.[citation needed] Some road safety activists use the term "road safety" (in quotes) to describe measures such as removal of "dangerous" trees and forced segregation of the vulnerable to the advantage of motorized traffic. Orthodox "road safety" opinion fails to address what Adams describes as the top half of the risk thermostat, the perceptions and attitudes of the road user community.[citation needed]

Criticisms

Some road-safety groups[who?] argue that the problem of road safety is largely being stated in the wrong terms because most road safety measures are designed to increase the safety of drivers, but many road traffic casualties are not drivers (in the UK only 40% of casualties are drivers), and those measures which increase driver safety may, perversely, increase the risk to these others, through risk compensation.[citation needed]

The core elements of the thesis are:[citation needed]

- that vulnerable road users are marginalised by the "road safety" establishment

- that "road safety" interventions are often centred around reducing the severity of results from dangerous behaviours, rather than reducing the dangerous behaviours themselves

- that improved "road safety" has often been achieved by making the roads so hostile that those most likely to be injured cannot use them at all

- that the increasing "safety" of cars and roads is often counteracted wholly or in part by driver responses (risk compensation).

RoadPeace and other groups have been strongly critical of what they see as moves to solve the problem of danger, posed to vulnerable road users by motor traffic, through increasing restrictions on vulnerable road users, an approach which they believe both blames the victim and fails to address the problem at source.[citation needed] This is discussed in detail by Dr Robert Davis in the book Death on the Streets: Cars and the mythology of road safety, and the core problem is also addressed in books by Professor John Adams, Mayer Hillman and others.[citation needed]

For example; the UK publishes Road Casualties Great Britain each year detailing reported road fatalities and injuries, claiming to have among the best pedestrian safety in Europe with falling injury rates, as measured in pedestrian KSI per head of population.[55] A study published by the British Medical Journal in 2006, suggested instead that the reduction in injury levels was due to lower levels of reporting, rather than the actual levels of injury as such.[56] Considerable under-reporting was confirmed by a second report prepared for the UK Department for Transport.[57] and the UK government now acknowledge the issue of under-reporting, but is not convinced that the reductions in reported injury levels do not reflect an actual decline.[58] Another independent report investigated if the roads were actually sufficiently dangerous as to deter pedestrians from using them at all.[59]

See also

- AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety (in the US)

- Assured Clear Distance Ahead

- Defensive driving

- Driving under the influence

- EuroRAP

- Fatality Analysis Reporting System

- Geometric design of roads

- Handicap International

- Highway Safety Manual

- ISO 39001

- List of countries by traffic-related death rate

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act

- Road Casualties Great Britain

- Rules of the road

- Speed limit

- Traffic collision

- Traffic psychology

- Traffic sign

- Road surface marking

- Road marking machine

- Transportation safety in the United States

- Turning Point (documentary)

- United Nations Road Safety Collaboration

- Work-related road safety in the United States

Notes and references

Notes

References

- ^ a b c International Transport Forum (2008). "Towards Zero, Ambitious Road Safety Targets and the Safe System Approach". OECD. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

It recognises that prevention efforts notwithstanding, road users will remain fallible and crashes will occur.

- ^ Statistical Annex, World report on road traffic injury prevention

- ^ "World report on road traffic injury prevention". World Health Organisation. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ "UN raises child accidents alarm". BBC News. 10 December 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ KSI league tables

- ^ Lovegrove G., Sayed T. (2006). "Macro-level collision models for evaluating neighbourhood traffic safety". Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering. 33: 609–621. doi:10.1139/l06-013.

- ^ "Speed Cameras". ROSPA.

The Cochrane Collaboration published out a second systematic review in 2006, which was updated in 2010. These studies only included before-and-after trials with comparison areas and interrupted time series studies.

- ^ "Reduce Injuries Associated with Motor Vehicle Crashes". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: CD004168. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004168.pub2.

Alcohol ignition interlock programmes for reducing drink driving recidivism.

- ^ a b "Traffic and Accident Data: Summary Statistics – Germany" (PDF). Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen (Federal Highway Research Institute). October 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Neighborhood Traffic Calming: Seattle's Traffic Circle Program http://www.usroads.com/journals/rmej/9801/rm980102.htm

- ^ Sun, J. & Lovegrove, G. (2008). Research Study on Evaluating the Level of Safety of the Fused Grid Road Pattern, External Research Project for CMHC, Ottawa, Ontario

- ^ Eric Dumbaugh and Robert Rae. Safe Urban Form: Revisiting the Relationship Between Community Design and Traffic Safety. Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 75, No. 3, Summer 2009

- ^ Vicky Feng Wei, BASc and Gord Lovegrove PhD (2011), Sustainable Road Safety: A New Neighbourhood Road Pattern that saves VRU Lives, University of British Columbia

- ^ "Reflective Glass Beads". Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ a b NEUMAN, TIMOTHY R.; et al. (2003). NCHRP REPORT 500 Volume 5: A Guide for Addressing Unsignalized Intersection Collisions (PDF). WASHINGTON, D.C.: TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD.

- ^ ANTONUCCI, NICHOLAS D.; et al. NCHRP REPORT 500 Volume 12: A Guide for Reducing Collisions at Signalized Intersections (PDF). Washington D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

- ^ "Cordova v. Ford, 46 Cal. App. 2d 180". 2. Official California Appellate Reports. 7 November 1966. p. 180. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

All courts are agreed that the mere fact of a collision of two automobiles gives rise to no inference of negligence against either driver in an action brought by the other. ...When a vehicle operated by A collides with a vehicle operated by B, there are four possibilities. A alone was negligent; B alone was negligent; both were negligent; or neither. Of these four only the first will result in liability of A to B. The bare fact of a collision affords no basis on which to conclude that it is the preponderant probability. The odds are against it.

See Official Reports Opinions Online - ^ A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets. Washington D.C.: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. 2004.

- ^ Geometric Design of Highways and Streets. American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials. 7 November 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

Exhibit 9-54. Time Gap for Case B1-Left turn from Stop

- ^ "Cal. Veh C. § 22101. Regulation of Turns at Intersection". State of California. 1 January 1975. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

When right- or left-hand turns are prohibited at an intersection notice of such prohibition shall be given by erection of a sign.

See opinions on C.V.C. § 22101: Official Reports Opinions Online - ^ Staplin, L.; et al. (2001). Highway Design Handbook for Older Drivers and Pedestrians. Washington D.C.: Federal Highway Administration.

- ^ "Vehicle Pedestrian Crashes". International Road Assessment Programme. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ^ "Vaccines for Roads; The new iRAP tools and their pilot application" (PDF). International Road Assessment Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ J.S.Dean. Murder most foul.

- ^ Matthias Schulz (16 November 2006). "European Cities Do Away with Traffic Signs". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ Ted White (September 2007). "Signing Off: Visionary traffic planners". Urbanite Baltimore. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ Gray, Sadie (11 January 2008). "Obituaries: Hans Monderman". The Times. London: Times Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ a b Andrew Gilligan (7 February 2008). "It's hell on the roads, and I know who's to blame". The Evening Standard. Associated Newspapers Limited. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ Professor John Adams (2 September 2007). "Shared Space – would it work in Los Angeles?" (PDF). John Adams. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ^ "Bringing U.S. Roads into the 21st Century".

- ^ "Primary and secondary prevention of drink driving by the use of alcolock device and program: Swedish experiences". 37 (6). Accident Analysis & Prevention. November 2005. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2005.06.020. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Driving Safety. http://www.nhtsa.gov/Safety/Motorcycles. NHTSA. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ Motorcycles: Traffic Safety Facts-2008 Data. http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/pubs/811159.pdf. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Williamson, Elizabeth (1 February 2005). "Brain Immaturity Could Explain Teen Crash Rate". Washington Post.

- ^ "The Good, the Bad and the Talented: Young Drivers' Perspectives on Good Driving and Learning to Drive" (PDF). Road Safety Research Report No. 74. Transport Research Laboratory. January 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ "Statistics database for transports". http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu (statistical database). Eurostat, European Commission. 20 April 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Vojtech Eksler, ed. (5 May 2013). "Intermediate report on the development of railway safety in the European Union 2013" (PDF). http://www.era.europa.eu (report). Safety Unit, European Railway Agency & European Union. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Star rating roads for safety: UK trials 2006-07". EuroRAP. 3 December 2007. (Note: see country maps here [2])

- ^ John Dawson, John. "Chairman's Message".

- ^ "Star rating roads for safety, UK trials 2006-07" (PDF). TRL, EuroRAP & ADAC. December 2007.

- ^ "Section 21, traffic officer numbers reduction in the UK" (PDF). Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ "page 147 Transport statistics 2009 edition" (PDF). Dft.gov.uk. 31 March 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811754AR.pdf

- ^ "Global status report on road safety 2013: Supporting a Decade of Action" (PDF) (report). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation WHO. 2013. ISBN 978-92-4-156456-4. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

data from 2010

- ^ "Visualizing Major Causes of Death in the 20th Century" (news article). Visual News. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ "Pedestrian Safety, Urban Space and Health: Summary Report" (PDF) (research report). Paris, France: International Transport Forum, OECD. 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ "Road Safety Annual Report 2014" (PDF) (report). Paris, France: International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group irtad, International Transport Forum, OECD. 2015. pp. 22, 32, div. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

data from 2013

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "About us". The AA. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ IRF Road Safety.

- ^ "Speed cameras.org". Speed cameras.org. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Nader v. General Motors Corp. Court of Appeals of New York, 1970

- ^ "about". World Day of Remembrance. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Session 60 Resolution 5. Improving global road safety A/RES/60/5 page 3. 26 October 2005. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ "Reported Road Casualties Great Britain: 2008 - Annual Report". UK Department for Transport. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Mike Gill, Michael J Goldacre, David G R Yeates (23 June 2006). "Changes in safety on England's roads: analysis of hospital statistics" (PDF). BMJ.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heather Ward, Ronan Lyons, Roselle Thoreau (June 2006). "Road Safety Research Report No. 69: Under-reporting of Road Casualties – Phase 1" (PDF). UK Department for Transport.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Reported Road Casualties Great Britain: 2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Department for Transport. p. 62. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

It has long been known that a considerable proportion of non-fatal casualties are not known to the police and hospital; survey and compensation claims data all indicate a higher number of casualties than are reported... Police data on road accidents (STATS19), whilst not perfect, remains the most detailed, complete and reliable single source of information on road casualties covering the whole of Great Britain, in particular for monitoring trends over time

- ^ One False Move. ISBN 0-85374-494-7. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

Sources

- World Health Organization (2013). "Global status report on road safety 2013". Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Department for Transport (2008). "Reported Road Casualties Great Britain: 2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Road Casualties Great Britain. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- Mayer Hillman, John Adams, John Whitelegg (2000) [1991]. One False Move: a study of children's independent mobility. Policy Studies Institute. ISBN 0-85374-494-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robert Davis (1993). Death on the Streets: Cars and the mythology of road safety. Leading Edge Press. ISBN 0-948135-46-8.

- John Adams (1995). Risk. UCL Press. ISBN 1-85728-068-7.

- Leonard Evans (2004). Traffic Safety. Science Serving Society. ISBN 0-9754871-0-8.

External links

- WHO road traffic injuries

- iRAP - International Road Assessment Programme

- International Transport Statistics Database

- Road Safety Toolkit

- ERSO - European Road Safety Observatory

- ETSC - European Transport Safety Council

- Journal of Safety Research

- The Cochrane Injuries Group

- Mortality from Road Crashes in 193 Countries: A Comparison with Other Leading Causes of Death, University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, February 2014

- - Making Road Safer