SARS-CoV-2

A request that this article title be changed to Wuhan coronavirus is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

This article may be affected by the following current event: 2019–20 Wuhan coronavirus outbreak. Information in this article may change rapidly as the event progresses. Initial news reports may be unreliable. The last updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. |

| Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) | |

|---|---|

| Transmission electron micrograph of two 2019-nCoV virions | |

| Transmission electron micrograph of two 2019-nCoV virions | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Nidovirales |

| Family: | Coronaviridae |

| Genus: | Betacoronavirus |

| Subgenus: | Sarbecovirus |

| Virus: | Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)

|

| Wuhan, China, the epicentre of the only recorded outbreak | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)[3][4], also known as the Wuhan coronavirus,[1] is a contagious virus that causes respiratory infection and has shown evidence of human-to-human transmission, first identified by authorities in Wuhan, Hubei, China, as the cause of the ongoing 2019-20 Wuhan coronavirus outbreak.[5] Genomic sequencing has shown that it is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA coronavirus.[6][7][8]

Due to reports that the the initial cases had epidemiological links to a large seafood and animal market, the virus is thought to have a zoonotic origin, though this has not been confirmed.[9] Comparisons of genetic sequences between this virus and other existing virus samples have shown similarities to SARS-CoV (79.5%)[10] and bat coronaviruses (96%)[10], with a likely origin in bats being theorized.[11][12][13]

Epidemiology

The first known outbreak of 2019-nCoV was detected in Wuhan, China, in mid-December 2019. The virus subsequently spread to other provinces of Mainland China and other countries, including Thailand, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia, France, and the United States.[14][15][16]

As of 27 January 2020, there were 2,886 confirmed cases of infection, of which 2,825 were within mainland China.[17] Cases outside China, to date, were people who have either travelled from Wuhan, or were in direct contact with someone who travelled from the area.[18] The number of deaths was 81 as of 27 January 2020.[17] Human-to-human spread was confirmed in Guangdong, China, on 20 January 2020.[19]

Symptoms

Reported symptoms have included fever, fatigue, dry cough, shortness of breath, and respiratory distress.[20][21] Cases of severe infection can result in pneumonia, kidney failure, and death.[22] In a statement issued on 23 January 2020, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stated that a quarter of those infected experienced severe disease, and that many of those who died had other conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease that impaired their immune systems.[23] A study of the first 41 patients admitted to hospitals in Wuhan with confirmed cases reported that a majority of the patients were healthy before contracting the infection, and that over a quarter of previously healthy individuals required intensive care.[24][25] Among the majority of those hospitalised, vital signs were stable on admission, and they had low white blood cells counts and low lymphocytes.[21]

Treatment

No specific treatment is currently available, so treatment is focused on alleviation of symptoms.[26] The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) is testing existing drug effectiveness for pneumonia.[27]

Existing anti-virals are being studied,[26] including protease inhibitors like indinavir, saquinavir, remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon beta.[28][29] The effectiveness of previously identified monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is also under investigation.[30]

Virology

Infection

Human-to-human transmission of the virus has been confirmed.[19] Reports have emerged that the virus is infectious even during the incubation period.[31][32] However, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States have stated that they "don't have any evidence of patients being infectious prior to symptom onset."[33]

One research group has estimated the basic reproduction number () of the virus to be between 3 and 5,[34] meaning it typically infects 3 to 5 people per established infection. Other research groups have estimated the basic reproduction number to be between 1.4 and 3.8.[35] It has been established that the virus is able to transmit along a chain of at least four people.[36]

Reservoir

Animals sold for food are suspected to be the reservoir or the intermediary because many of the first identified infected individuals were workers at the Huanan Seafood Market. Consequently, they were exposed to greater contact with animals.[21] A market selling live animals for food was also blamed in the SARS epidemic in 2003; such markets are considered a perfect incubator for novel pathogens.[37]

With a sufficient number of sequenced genomes, it is possible to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree of the mutation history of a family of viruses. During 17 years of research on the origin of the SARS 2003 epidemic, many SARS-like bat coronaviruses were isolated and sequenced, most of them originating from the Rhinolophus genus of bats. The Wuhan novel coronavirus has been found to fall into this category of SARS-related coronaviruses. Two genome sequences from Rhinolophus sinicus published in 2015 and 2017 show a resemblance of 80% to 2019-nCoV.[11][12] A third unpublished virus genome from Rhinolophus affinis "RaTG13" with a resemblance of 96% to 2019-nCoV has also been noted.[38] For comparison, this amount of variation among viruses is similar to the amount of mutation observed over ten years in the H3N2 human flu virus strain.[39]

Phylogenetics and taxonomy

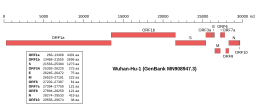

Genome organisation (click to enlarge) | |

| NCBI genome ID | MN908947 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 30,473 bases |

| Year of completion | 2020 |

2019-nCoV belongs to the broad family of viruses known as coronaviruses. Other coronaviruses are capable of causing illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). It is the seventh known coronavirus to infect people, after 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV.[40]

Though genetically distinct from other coronaviruses that infect humans, it is, like SARS-COV, a member of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (Beta-CoV lineage B).[41][21][42] Its RNA sequence is approximately 30 kb in length.[8]

By 12 January, five genomes of the novel coronavirus had been isolated from Wuhan and reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and other institutions;[8][43][44] the number of genomes increased to 28 by 26 January. Except for the earliest GenBank genome, the genomes are under an embargo at GISAID. A phylogenic analysis for the samples is available through Nextstrain.[45]

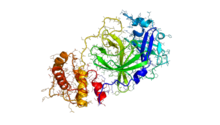

Structural biology

The publications of the genome led to several protein modeling experiments on the receptor binding protein (RBD) of the nCoV spike (S) protein suggesting that the S protein retained sufficient affinity to the Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor to use it as a mechanism of cell entry.[47] On 22 January, a group in China working with the full virus and a group in the U.S. working with reverse genetics independently and experimentally demonstrated ACE2 as the receptor for 2019-nCoV.[48][49][50]

To look for potential protease inhibitors, the viral 3C-like protease M(pro) from the Orf1a polyprotein was also modeled for drug docking experiments. Innophore has produced two computational models based on SARS protease,[46] and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Rao ZH, Yang HT) has produced an unpublished experimental structure of a recombinant 2019-nCoV protease.[51]

Vaccine research

In January 2020, several organizations and institutions began work on creating vaccines for the Wuhan coronavirus based on the published genome.[52][53] In China, the CCDC has started developing vaccines against the novel coronavirus.[54][55]

Three vaccine projects are being supported by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), including one project by the biotechnology company Moderna and another by the University of Queensland.[56] The United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) is cooperating with Moderna to create an RNA vaccine matching a spike of the coronavirus surface, and is hoping to start production by May 2020.[52] In Australia, the University of Queensland is investigating the potential of a molecular clamp vaccine that would genetically modify viral proteins to make them mimic the coronavirus and stimulate an immune reaction.[56]

In an independent project, the Public Health Agency of Canada has granted permission to the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization – International Vaccine Centre (VIDO-InterVac) at the University of Saskatchewan to begin work on a vaccine.[57] VIDO-InterVac aims to start production and animal testing in March 2020, and human testing in 2021.[53]

References

- ^ a b Fox, Dan (2020). "What you need to know about the Wuhan coronavirus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00209-y. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Zhang, Y.-Z.; et al. (12 January 2020). "Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, complete genome". GenBank. Bethesda, Maryland, United States: National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ "Surveillance case definitions for human infection with novel coronavirus (nCoV)". World Health Organization. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Wuhan, China". United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019 nCoV): Frequently Asked Questions | IDPH". www.dph.illinois.gov. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "中国疾病预防控制中心" (in Chinese). People's Republic of China: Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ "New-type coronavirus causes pneumonia in Wuhan: expert". People's Republic of China. Xinhua. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "CoV2020". platform.gisaid.org. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ http://www.nj.gov/health/cd/documents/topics/NCOV/NCoV_LINCS_wuhan_update_011820_combined.pdf

- ^ a b http://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.22.914952v1.full.pdf

- ^ a b Sample CoVZC45 and CoVZXC21, see there for an interactive visualisation

- ^ a b "The 2019 new Coronavirus epidemic: evidence for virus evolution". doi:10.1101/2020.01.24.915157v1 (inactive 25 January 2020).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2020 (link) - ^ Callaway, Ewen; Cyranoski, David (23 January 2020). "Why snakes probably aren't spreading the new China virus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00180-8.

- ^ "China coronavirus: Hong Kong widens criteria for suspected cases after second patient confirmed, as MTR cancels Wuhan train ticket sales". Hong Kong: South China Morning Post. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus: three cases reported in France". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 January 2020.

- ^ Doherty, Ben (25 January 2020). "Coronavirus: three cases in NSW and one in Victoria as infection reaches Australia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS". gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT - 5 25 JANUARY 2020" (PDF). Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b "China confirms human-to-human transmission of new coronavirus". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Experts explain the latest bulletin of unknown cause of viral pneumonia". Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, Ippolito G, Mchugh TD, Memish ZA, Drosten C, Zumla A, Petersen E. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Jan 14;91:264–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. PMID 31953166.

- ^ "Q&A on coronaviruses". www.who.int. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's statement on the advice of the IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus". www.who.int.

- ^ Joseph, Andrew (24 January 2020). "New coronavirus can cause infections with no symptoms and sicken otherwise healthy people, studies show". STAT. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (24 January 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet: S0140673620301835. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

- ^ "China CDC developing novel coronavirus vaccine". Xinhua. 26 January 2020.

- ^ Paules, Catharine I.; Marston, Hilary D.; Fauci, Anthony S. (23 January 2020). "Coronavirus Infections—More Than Just the Common Cold". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0757. PMID 31971553.

- ^ "Gilead assessing Ebola drug as possible coronavirus treatment". Reuters. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Vir Biotechnology and Novavax announce vaccine plans-GB". Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "【武漢肺炎】衛健委︰新型冠狀病毒傳播力增強 潛伏期最短僅1天". 明報新聞網 (in CN).

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "专家:病毒潜伏期有传染性 有人传染同事后才发病". news.163.com (in CN). 26 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ U.S. Notches Fifth Coronavirus Case as Global Count Nears 3,000

- ^ Zhao, Shi; Ran, Jinjun; Musa, Salihu Sabiu; Yang, Guangpu; Lou, Yijun; Gao, Daozhou; Yang, Lin; He, Daihai (24 January 2020). "Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: A data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak". bioRxiv: 2020.01.23.916395. doi:10.1101/2020.01.23.916395.

- ^ Liu, Tao; Hu, Jianxiong; Kang, Min; Lin, Lifeng; Zhong, Haojie; Xiao, Jianpeng; He, Guanhao; Song, Tie; Huang, Qiong; Rong, Zuhua; Deng, Aiping; Zeng, Weilin; Tan, Xiaohua; Zeng, Siqing; Zhu, Zhihua; Li, Jiansen; Wan, Donghua; Lu, Jing; Deng, Huihong; He, Jianfeng; Ma, Wenjun (25 January 2020). "Transmission dynamics of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". bioRxiv: 2020.01.25.919787. doi:10.1101/2020.01.25.919787.

- ^ Saey, Tina Hesman (24 January 2020). "How the new coronavirus stacks up against SARS and MERS". Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Myers, Steven Lee (25 January 2020). "China's Omnivorous Markets Are in the Eye of a Lethal Outbreak Once Again". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Wuhan Institue of Virology (23 January 2020). "Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.01.22.914952v2 (inactive 25 January 2020). Retrieved 24 January 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2020 (link) - ^ "auspice". nextstrain.org.

- ^ Zhu, Na; Zhang, Dingyu; Wang, Wenling; Li, Xinwang; Yang, Bo; Song, Jingdong; Zhao, Xiang; Huang, Baoying; Shi, Weifeng; Lu, Roujian; Niu, Peihua; Zhan, Faxian; Ma, Xuejun; Wang, Dayan; Xu, Wenbo; Wu, Guizhen; Gao, George F.; Tan, Wenjie (24 January 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". New England Journal of Medicine. 0. United States. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ^ "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". nextstrain. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Antonio C. P. Wong, Xin Li, Susanna K. P. Lau, Patrick C. Y. Woo. Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses. Viruses. 2019 Feb;11(2):174. doi:10.3390/v11020174.

- ^ "Initial genome release of novel coronavirus". Virological. 11 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, complete genome". National Center for Biotechnology Information. United States: National Institutes of Health. 17 January 2020.

- ^ Bedford, Trevor; Neher, Richard. "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus (nCoV) using data generated by Fudan University, China CDC, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Zhejiang Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Thai National Institute of Health shared via GISAID". nextstrain.org. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Gruber, Christian; Steinkellner, Georg (23 January 2020). "Wuhan coronavirus 2019-nCoV - what we can find out on a structural bioinformatics level". Innophore Enzyme Discovery. Innophore GmbH.

- ^ "Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission". SCIENCE CHINA Life Sciences. doi:10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5 (inactive 24 January 2020). Retrieved 23 January 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2020 (link) - ^ Letko, Michael; Munster, Vincent (22 January 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for lineage B β-coronaviruses, including 2019-nCoV". BiorXiv. doi:10.1101/2020.01.22.915660. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ Zhou, Peng; Shi, Zheng-Li (2020). "Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin". BiorXiv. doi:10.1101/2020.01.22.914952. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ Gralinski, Lisa E.; Menachery, Vineet D. (2020). "Return of the Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV". Viruses. 12 (2): 135. doi:10.3390/v12020135.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "上海药物所和上海科技大学联合发现一批可能对新型肺炎有治疗作用的老药和中药". Chinese Academy of Sciences. 25 January 2020.

- ^ a b Steenhuysen, Julie; Kelland, Kate (24 January 2020). "With Wuhan virus genetic code in hand, scientists begin work on a vaccine". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Saskatchewan lab joins global effort to develop coronavirus vaccine". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "China CDC developing novel coronavirus vaccine". Xinhua. 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Chinese scientists race to develop vaccine as coronavirus death toll jumps". SCMP. 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b Devlin, Hannah (24 January 2020). "Lessons from Sars outbreak help in race for coronavirus vaccine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Saskatchewan lab joins global effort to develop coronavirus vaccine". ca.news.yahoo.com.