St Peter upon Cornhill

| St Peter upon Cornhill | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | London, EC3 |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholicism |

| Churchmanship | Conservative evangelical |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed building |

| Architect(s) | Christopher Wren |

| Style | Baroque |

| Years built | 1667 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | London |

| Parish | St Helen's Bishopsgate |

St Peter upon Cornhill is an Anglican church on the corner of Cornhill and Gracechurch Street in the City of London of medieval, or possibly Roman origin. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren. It lies in the ward of Cornhill.

It is now a satellite church in the parish of St Helen's Bishopsgate and home of St Helen's 10am congregation, which meets here for regular services on Sunday mornings and for mid-week Bible studies.

Early history

[edit]Roman location

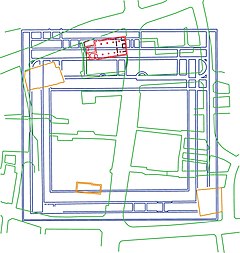

[edit]The church stands on the highest point of the City of London, directly above the foundations of the great London Roman basilica (built c. AD 90–120). The east end of the church, and its high altar, are also positioned above the area where some basilicas of the period had a pagan shrine room (also known as an aedes).[1]

The possible existence of the shrine room is supported by nineteenth-century excavations under Gracechurch Street, immediately adjacent to the church's eastern end. These unearthed an adjoining room covered in yellow panels with a black border, 'with a tessellated floor, suggesting it may have had a higher status than normal, possibly acting as an antechamber for the aedes or shrine-room'.[2] The alignment of the church is close to the lines of the basilica, being off by just two degrees and it is feasible for the understructure to have utilized the dry solid 2nd-century basilica wall fabric for support.[3]

A tradition grew up that the church was founded by Lucius, the first Christian king in Britain sometime after his conversion in AD179. He dedicated it to St Peter the Apostle and the church became the seat of an archbishop until the coming of the Saxons in the 5th century, after which London was abandoned and Canterbury became the seat for the 6th-century Gregorian mission to the Kingdom of Kent.[4] If St Peter's was built in the Roman era, it would make the church possibly contemporaneous to the Romano-British church at Silchester, similarly built adjacent to the Roman Basilica and most likely pre-Constantine in age.[5][6]

The London Roman basilica, with most of the forum to the south, is thought to have been largely demolished around 300 AD,[7] with building material being removed (possibly for other projects) and the land levelled and eventually covered with a thick layer of dark soil. Whether St Peter's was in existence at this point, and continued to serve as a place of worship, or whether the Lucius story is a fable and the first St Peter's was only established many centuries later may only be determined by future archaeological investigation under the present church.

Two other facts however, may give credence to a Roman past. The first is that it is known that London sent a bishop, Restitutus, to the Council of Arles in 314 AD. Restitutus must have had a church base serving a local christian community. The only other suggested alternative to St Peter's is an enormous aisled building excavated in 1993 near Tower Hill. This however dates to 350-400AD, several decades after Bishop Resitutus. The Tower Hill building was big, and similar in size and lay-out to the 4th-century Cathedral of St Tecla in Milan, the largest church in the Roman Empire at the time. Although the identity of this building is still subject to speculation, the evidence seems to favour it being a church.[8] Interestingly it was built a few decades after the great Roman Basilica in London was demolished, and was constructed from re-used material, so the defunct Basilica seems an obvious source.[9]

Secondly, there are two medieval references to the church having Roman roots in the way that the three other medieval churches also sited on the basilica / forum site did not. A long lost book by Jocelyn of Furness (1175–1214), cited by John Stow, and perhaps written just over 150 years after our first known reference to St Peters (1038), states that St Peter's was built by King Lucius.[10] In 1417, the Mayor of London also determined (during a dispute) that St Peter's was the first church founded in London.[11] Given that St Paul's Cathedral was founded in 604, this clearly implies that Londoners in 1417 considered St Peters to have been founded pre-600.[12]

There is, however, some conflicting evidence to the theory that St Peter's was deliberately cited above a pagan shrine room. Current research suggests it very rare for early English Christian churches to be founded in pagan temples,[13] and that when temples were turned into churches, this occurred later, in the late sixth century and onwards.[14] This was also true elsewhere in the Roman Empire; for example in Rome. By this time the former associations of the sites had probably died down.[15]

Nonetheless there is precedent for early Christian churches and cathedrals to be built over Roman imperial structures and also on hills and geographic high points. Shortly after the London Basilica was demolished the Emperor Constantine authorised new major church buildings in Rome including St John's Lateran on the Lateran Hill (AD 313) and Saint Peter's on the Vatican Hill (AD 318).

King Lucius plaque

[edit]The London historian John Stow, writing at the end of the 16th century, reported "there remaineth in this church a table whereon is written, I know not by what authority, but of a late hand, that King Lucius founded the same church to be an archbishop's see metropolitan,[16] and chief church of his kingdom, and that it so endured for four hundred years".[17] The "table" (tablet) seen by Stow was destroyed when the medieval church was burnt in the Great Fire of London,[18] but before this time a number of writers had recorded what it said. The text of the original tablet as printed by John Weever in 1631 began:

Be hit known to al men, that the yeerys of our Lord God an clxxix [AD 179]. Lucius the fyrst christen kyng of this lond, then callyd Brytayne, fowndyd the fyrst chyrch in London, that is to sey, the Chyrch of Sent Peter apon Cornhyl, and he fowndyd ther an Archbishoppys See, and made that Chirch the Metropolitant, and cheef Chirch of this kingdom...[19]

A replacement, in the form of an inscribed brass plate, was set up after the Great Fire[18] and still hangs in the church vestry. The text of the brass plate has been printed several times, for example by George Godwin in 1839,[20] and an engraving of it was included in Robert Wilkinson's Londina Illustrata (1819–25).[21]

Medieval church

[edit]Regardless of the Lucius connection, St Peter's is clearly one of the earliest churches in London. The date of the medieval church is uncertain but the first definitive reference was around 1038, when Ælfric II, bishop of Elmham, left a messuage (a dwelling with adjacent buildings and land) in his will to "St. Peter binnon Lunden" (St Peter in London).[22] In 1156 it is mentioned in a charter of Henry II.

By 1226 it was of sufficient importance to have three chaplains. They were referred to as co-conspirators in the somewhat gruesome murder of a deacon of St Peter's, Amise, who had been stabbed to death by the vicar of St. Paul's, London.[23] A list of vicars in the church records the first known appointment as one John de Cabanicig in 1263, with the patronage being claimed by Pope Urban IV for 'long voidance'.[24] In 1444 a "horsemill" was given to St Peter's. The bells of St Peter are mentioned in 1552, when a bell foundry in Aldgate was asked to cast a new bell.

Medieval school & scriptorium

[edit]In addition to its early foundation, St Peter's was clearly an important church in London. In 1447 Parliament under Henry VI ordained that it should host one of the four parochial schools in London; the other schools included the cathedral schools of St Paul's and Westminster.[25]

It also possessed a fine and ancient library and scriptorium, in use up to circa 1548. Sir John Crosby (died 1475) left money for the repairing of the library in his will.[26] It also contained a manuscript copy of the St. Jerome Vulgate that was written there in 1290. However, this adjoining library 'is no longer extant and its exact location is not certain'.[27]

Present building

[edit]

The medieval church was badly damaged in the Great Fire of London in 1666. The parish tried to patch it up, but between 1677 and 1684 it was rebuilt to a design by Christopher Wren at a cost of £5,647.[citation needed] The new church was 10 feet (3.0 m) shorter than its predecessor, the eastern end of the site having been given up to widen Gracechurch Street.[28]

St Peter's was described by Ian Nairn as having "three personalities inextricably sewn into the City".[29] The eastern frontage to Gracechurch Street is a grand stone-faced composition, with five arched windows between Ionic pilasters above a high stylobate (column base). The pilasters support an entablature; above that is a blank attic storey, then a gable with one arched window flanked by two round ones. The north and south sides are stuccoed and much simpler in style. Unusually, shallow 19th-century shops have survived towards Cornhill, squeezed between the church and the pavement. The tower is of brick, its leaded cupola topped with a small spire, which is in turn surmounted by a weather vane in the shape of St Peter's key.[20][30]

The interior is aisled, with square arcade piers[31] resting on the medieval pier foundations. The nave is barrel vaulted, while the aisles have transverse barrel vaults.[30] Unusually for a Wren church, there is a screen marking the division between nave and chancel. This was installed at the insistence of the rector at the time of rebuilding, William Beveridge.[32]

St Peter's was formerly the regimental church of the Royal Tank Regiment, having been adopted as such in 1954 at the suggestion of the then rector, Douglas Owen, who had served as a Padre with the regiment. Since 2007 the regimental church has been St Mary Aldermary.[33]

The church was designated a Grade I listed building on 4 January 1950.[34] It is now a satellite church in the parish of St Helen's Bishopsgate and is used for staff training, Bible studies and a youth club. The St Helen's church office controls access to St Peter's.[35]

Charles Dickens mentions the churchyard in Our Mutual Friend. A theatre group called The Players of St Peter were formed at the church in 1946 and performed there until 1987.[36] They are now based at St Clement Eastcheap where its members perform medieval mystery plays each November.

Features and points of interest

[edit]

Music

[edit]In June 1834 14-year-old Elizabeth Mounsey became the organist of St Peter's. She remained in the position for 48 years, until her resignation in 1882.[37] The organ in the gallery of St Peter's has an autographed souvenir quote from a J.S. Bach passacaglia on display, which Felix Mendelssohn gave to Mounsey on 30 September 1840 after he gave an impromptu performance on the church's organ.[38]

Jowett

[edit]In the 1830s, the notable missionary William Jowett was a lecturer at the church.[39]

Burials

[edit]-

Churchyard seats

-

Small garden

-

From corner of Cornhill and Gracechurch Street

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ R.E.M. Wheeler, The Topography of Saxon London, p296, Antiquity , Volume 8, Issue 31, September 1934.

- ^ A Reassessment of the Second Basilica in London, A. D. 100-400: Excavations at Leadenhall Court, 1984-86, T. Brigham, Britannia, Vol. 21 (1990), p92

- ^ King Lucius of Britain, David Knight, 2008 p98.

- ^ Thomas Allen, Thomas Wright The History and Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark and Parts Adjacent Vol 3,1839, publisher George Virtue,London,pp 447–450

- ^ King, Anthony (1983). "The Roman Church at Silchester Reconsidered". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 2 (2): 225–237. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1983.tb00108.x. ISSN 1468-0092.

- ^ Petts, David (5 October 2015). Millett, Martin; Revell, Louise; Moore, Alison (eds.). Christianity in Roman Britain. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697731.013.036. ISBN 978-0-19-969773-1.

- ^ The King Lucius tabula in St Peter Upon Cornhill church, London, John Clark, revised 1 April 2014, page 14, accessed 17 January 2022

- ^ London in the Roman World, Dominic Perring, OUP Oxford (27 Jan. 2022), p373 (Kindle version)

- ^ Archaeologists unearth capital's first cathedral, David Kays, The Independent Newspaper, 3 April 1995, accessed 12 June 2022

- ^ A Survey of London. Reprinted From the Text of 1603. Originally published by Clarendon, Oxford, 1908,pp125-126, accessed 25 October 2022

- ^ The King Lucius Tabula, John Clark (2014), p7, accessed 17 January 2022

- ^ David Knight, 2008, p 83

- ^ Tyler W Bell, The Religious Reuse of Roman Structures in Anglo-Saxon England, 2001, p105 and p109 - only 2 churches have been found that are sited on a Roman temple, just 0.7% of the total, accessed 26 Sep 2022

- ^ Tyler W Bell, The Religious Reuse of Roman Structures in Anglo-Saxon England, 2001, p108, accessed 26 Sep 2022

- ^ The Conversion of Temples in Rome, Feyo L. Schuddeboom, Journal of Late Antiquity, 22 September 2017, p175

- ^ "The City of London Churches: monuments of another age" Quantrill, E; Quantrill, M p88: London; Quartet; 1975

- ^ Stow, John (1842). A Survey of London, Written in the Year 1598. London: Whittaker & Co. p. 73.

- ^ a b Newcourt, Richard (1708). Repertorium Ecclesiasticum Parochiale Londinense: An Ecclesiastical Parochial History of the Diocese of London. Vol. I. London: C. Bateman. p. 522.

- ^ Weever, John (1631). Ancient Funerall Monuments. London. p. 413.

- ^ a b Godwin, George; John Britton (1839). The Churches of London: A History and Description of the Ecclesiastical Edifices of the Metropolis. London: C. Tilt.

- ^ Wilkinson, Robert (1819–25). Londina Illustrata. London: Robert Wilkinson. An illustration of Wilkinson's engraving is accessible at "Reduced facsimile copy of the brass plate in the Church of St. Peter upon Cornhill". Tufts University. hdl:10427/54651.

- ^ See The Electronic Sawyer, Online catalogue of Anglo-Saxon charters, University of Cambridge, S1489, accessed 17 January 2022. See original text and translation on Anglo-Saxons.net, accessed 17 January 2022; and also Henry A Harben, 'Peltry (The) - Peter (St.) de Bradestrate, Broadstreet', in A Dictionary of London (London, 1918),British History Online accessed 16 January 2022.

- ^ Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, Volume 4, 1875, St Peter's Church, Cornhill, by the Rev. Richard Whittington, M.A. Vicar. p302, accessed 12 June 2022

- ^ A Manuscript list of 'Rectors of Saint Peter Upon Cornhill', hanging in the church, viewed 7 February 2022. The authority cited for this entry is 'Royal Letters, Vol IV, p 413.

- ^ Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, Volume 4, 1875, St Peter's Church, Cornhill, by the Rev. Richard Whittington, M.A. Vicar. p302, accessed 12 June 2022

- ^ The Tomb, the Palace and a Touch of Shakespeare: The Memory of Sir John Crosby, Christian Steer, 2006, The Riccardian, p5, accessed 6 February 2022

- ^ David Knight, King Lucius, 2008,p 101

- ^ Jenkinson, Wilberforce (1917). London Churches Before the Great Fire. London: Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge. pp. 120–3.

- ^ Nairn, Ian (1966). Nairn's London. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 27.

- ^ a b Bradley, Simon and Pevsner, Nikolaus. London: The City Churches. New Haven, Yale, 1998. ISBN 0-300-09655-0 p.123

- ^ Malcolm, James Peller (1807). Londinium Redivivium, or, an Ancient History and Modern Description of London. Vol. 4. London.

- ^ Hatts, Leigh. London City Churches, 2003, p.84 ISBN 978-0-9545705-0-7

- ^ "Regimental Church & Collect". Royal Tank Regiment. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1192245)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ "St Helens Bishopsgate". Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ^ Players of St Peter cast lists Archived 23 December 2012 at archive.today

- ^ The Englishwoman's Review of Social and Industrial Questions: 1882 (Reprint ed.). Routledge. 2016. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-315-40352-6.

- ^ Musical Times, 1 November 1905, page 719 - In addition to the Passacaglia, he played Bach's Prelude and Fugue in E minor, and his own Prelude and Fugue in C minor, Op. 37, No. 1 and another fugue in F minor.

- ^ Goodwin, G., revised by H. C. G. Matthew, 'Jowett, William (1787–1855), missionary', in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004)

External links

[edit]- St Peter upon Cornhill from Friends of the City Churches

- Emporis.com[usurped]

- UK Attraction

- Set of 60 photographs of St Peter upon Cornhill Church by Rex Harris

- 1815 Seat plan of St Peter upon Cornhill Church

- St Helen's Bishopsgate