Supermarine Southampton

| Southampton | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Military reconnaissance flying boat |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Supermarine |

| Status | Out of service |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 83[1] |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1924–1934 |

| Introduction date | 1925 |

| First flight | 10 March 1925 |

| Developed from | Supermarine Swan |

| Variants | Supermarine Nanok Supermarine Scapa |

The Supermarine Southampton was a flying boat of the interwar period designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Supermarine. It was one of the most successful flying boats of the era.

The Southampton was derived from the experimental Supermarine Swan, and thus was developed at a relatively high pace. The design of the Southampton represented a new standard for maritime aircraft, and was a major accomplishment for Supermarine's design team, headed by R. J. Mitchell. Supermarine had to expand its production capacity to keep up with demand for the type.

During August 1925, the Southampton entered service with the Royal Air Force. The aircraft had gained a favourable reputation as the result of a series of long-distance flights. Further customers emerged for the type, including the Imperial Japanese Navy, Argentine Naval Aviation, and the Royal Danish Navy. The aircraft were adopted by civilian operators, such as Imperial Airways and Japan Air Transport. Amongst other feats, the Southampton facilitated an early 10-passenger cross-channel airline service between England and France.

Development

[edit]Background

[edit]The Southampton's origins can be traced to an earlier experimental aircraft designed by R.J. Mitchell at Supermarine, the Swan, which made its maiden flight on 25 March 1924. During this time, the Royal Air Force (RAF) was close to giving up on the procurement of effective large flying boats, having been disappointed by types such as the Felixstowe F.5.[2] Having been impressed by the Swan's performance during trials at RAF Felixstowe, the British Air Ministry generated Specification R.18/24 and ordered a batch of six production Southamptons from Supermarine. Unusually, a prototype was never built and tested, an indication of the Air Ministry's confidence in Mitchell's design.[3]

The development time was relatively compact. Simplicity was a key philosophy practised by Mitchell and his design team, an example with e Southampton being the avoidance of the traditional use of cross-bracing wires between the wings. Traditional manufacturing practices of the era were spurned in favour of new approaches, such as the deliberate avoidance of integrating the lower wing with the fuselage to leave the decking and inner wing section free to be independently worked upon.[4]

Production and test trials

[edit]On 10 March 1925, the maiden flight of the first production aircraft was conducted; piloted by Henry Charles Biard.[5] While this flight was largely successful, one of the wingtip floats sustained minor damage, leading to their angle of incidence being quickly adjusted to prevent reoccurrence prior to their complete redesign later on. Four days later, the contractor's trials were completed, thus the Southampton was promptly flown to Felixstowe, where it underwent type trials. These were passed with relative ease, including its ability to maintain altitude on only a single engine, leading to the aircraft's formal delivery to the RAF occurring during mid-1925.[5]

Following the completion of the initial six aircraft, further orders for the Southampton were promptly received. Supermarine lacked the factory capacity to keep up with demand, thus an additional facility were acquired on the other side of Southampton Water, after which production of the type was centred in this location.[5] Throughout the type's production run, the Southampton's design continued to be refined; changes included improved engines models and the substitution of the wooden hull and its wings with metal (duralumin) counterparts.[6] By the end of production, a total of 83 Southamptons were constructed, excluding the three-engined Southampton MK X, which was a single prototype.[1]

Several models and derivates of the Southampton were developed; it was effectively replaced in production by the Supermarine Scapa, which was one such derivative.[7]

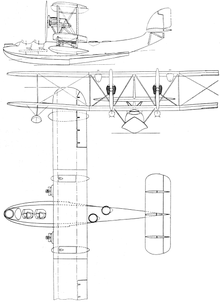

Design

[edit]The Supermarine Southampton was a twin-engine biplane flying boat, which was typically powered by a pair of Napier Lion twelve-cylinder engines. The engines are mount on pylons positioned between the wings in a tractor configuration. The engine installation enabled both maintenance and engine swaps to be performed without any interaction with the wing structure. Fuel was gravity-fed to the engines from tanks within the upper wings, the fuselage was kept free of any fuel lines, aside from a fuel pump used to refill the wingtanks from an aft sump while at anchor. The crew were positioned so that they could readily communicate with one another There were three positions for machine guns, one set upon the nose and two staggered towards either side of the rear fuselage. These rear gunners had a relatively favourable field of fire.[3]

The Southampton's structure was revised substantially over successive batches. The Southampton Mk I had both its hull and its wings manufactured from wood, while the Southampton Mk II had a hull with a single thickness of metal (duralumin) (the Mk I had a double wooden bottom); this change gave an effective weight saving of 900 lb (410 kg) (of this 900 lb, 500 lb (230 kg) represented the lighter hull, while the remaining 400 lb (180 kg) represented the weight of water that could be soaked up by the wooden hull) allowing for an increase in range of approximately 200 mi (320 km).{ All metallic elements were anodised to deter corrosion. During 1929, 24 of the Southampton Mk Is were converted by having newly built metal hulls replacing the wooden ones.[6] Later on, the type was also furnished with metal propellers produced by Leitner-Watts.[8] Some of the later aircraft were built with metal wings and were probably designated as Southampton Mk III, although this designation's usage has been disputed.[9]

Operational history

[edit]During August 1925, the first Southamptons entered service with the RAF, the type being initially assigned to No. 480 (Coastal Reconnaissance) Flight, based at RAF Calshot.[7] As validated through a series of exercises, the ability of the Southampton to independently operate, even within inhospitable weather conditions, was well proven.[10] Andrews and Morgan observed that the Southampton quickly proved itself to have primacy amongst European flying boats of the era, a fact that was promptly demonstrated by its overseas activities.[11]

Amongst the tasks of which RAF Southamptons performed was a series of "showing the flag" long-distance formation flights. Perhaps the most notable of these flights was a 43,500 km (27,000 mi) expedition conducted during 1927 and 1928; it was carried out by four Southamptons of the Far East Flight, setting out from Felixstowe via the Mediterranean and India to Singapore.[12] These aircraft featured various technical changes, including enlarged fuel tanks composed of tinned steel, increased oil tankage, greater radiator surface area, and the removal of all armaments. According to Andrews and Morgan, the Southampton acquired considerable fame amongst the general public from these flights; Supermarine also shared in this reputation gain.[13] There were also practical benefits of these flights, as new anti-corrosion techniques were developed as a result of feedback.[14]

While the RAF was the type's most high-profile customer, further Southamptons were sold to a number of other countries. Eight new aircraft were sold to Argentina, with Turkey purchasing six aircraft and Australia buying two ex-RAF Mk 1 aircraft.[15] Japan also purchased a single aircraft which was later converted into an 18-passenger cabin airliner. The United States Navy also requested a quote, but no order materialised.[16] One RAF aircraft was loaned to Imperial Airways, with British Civil Registration G-AASH, for three months from December 1929 to replace a crashed Short Calcutta on the airmail run between Genoa and Alexandria.[17][18]

Variants

[edit]Different powerplants were fitted in variants:

- Mk I

- Napier Lion V engines, wooden hull. 23 built.[19]

- Mk II

- Napier Lion Va, 39 built[20]

- Saunders A.14

- Argentina

- Lorraine-Dietrich 12E. Five wooden-hulled + three metal-hulled aircraft.[19]

- Turkey

- Hispano-Suiza 12Nbr. Six built.[21]

- Bristol Jupiter IX and Rolls-Royce Kestrel in experiments

- Mk IV Supermarine Scapa prototype

Operators

[edit]

Military operators

[edit]- Royal Australian Air Force

- No. 1 Flying Training School's Seaplane Squadron RAAF

Civil operators

[edit]Surviving aircraft

[edit]The restored wooden fuselage of Supermarine Southampton 1 N9899 is on display at the Royal Air Force Museum in Hendon.[25]

Specifications (Southampton II)

[edit]

Data from Supermarine Aircraft since 1914[26]

General characteristics

- Length: 49 ft 8+1⁄2 in (15.151 m)

- Wingspan: 75 ft 0 in (22.86 m)

- Height: 20 ft 5 in (6.22 m)

- Wing area: 1,448 sq ft (134.5 m2)

- Empty weight: 9,697 lb (4,398 kg)

- Gross weight: 15,200 lb (6,895 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 18,000 lb (8,165 kg) (overload)[27]

- Powerplant: 2 × Napier Lion VA inline W-block, 500 hp (370 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 95 mph (153 km/h, 83 kn) at sea level

- Range: 544 mi (875 km, 473 nmi) at 86 mph (75 kn; 138 km/h) and 2,000 ft (610 m)

- Endurance: 6.3 hours

- Service ceiling: 5,950 ft (1,810 m)

- Absolute ceiling: 8,100 ft (2,500 m)

- Rate of climb: 368 ft/min (1.87 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 29 minutes, 42 seconds to 6,000 ft (1,800 m)

Armament

- Guns: Three × .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis guns, one in bows and two amidships

- Bombs: 1,100 lb of bombs under the wings

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

[edit]- ^ a b Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 358.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 90, 96–97.

- ^ a b Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 97.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b c Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 98.

- ^ a b Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 100.

- ^ a b Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 111.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 106–107.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 104–106.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 98–99.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 100–104.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 99–102.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 100–103.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 108.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 109–111.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 104.

- ^ Jackson 1974, p. 443.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b Andrews & Morgan 1987, p. 357.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1987, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1987, p. 358.

- ^ Thetford 1958, p. 385.

- ^ Stroud 1986, p. 214.

- ^ Jackson 1978, pp. 445–446.

- ^ "Individual History: Supermarine Southampton 1 N9899" (PDF). rafmuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 112.

- ^ Kightly 2020, p. 80.

- ^ Ransom and Fairclough, S and R (1987). "English Electric Aircraft and their Predecessors". Their Fighting Machines. Putnam. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Andrews, Charles Ferdinand; Morgan, Eric B. (1981). Supermarine Aircraft since 1914. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-370-10018-0.

- Andrews, Charles Ferdinand; Morgan, Eric B. (1987). Supermarine Aircraft since 1914. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-85177-800-6..

- Jackson, A. J. (1974). British Civil Aircraft since 1919. Vol. 3. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-370-10014-2.

- Jackson, A. J. (1978). "Civil Southampton". Aeroplane Monthly. Vol. 6, no. 6. pp. 444–446.

- Kightly, James (2020). "Database: Supermarine Southampton". Aeroplane Monthly. Vol. 48, no. 4. pp. 75–87. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Stroud, John (1986). "Wings of Peace". Aeroplane Monthly. Vol. 14, no. 4. p. 214. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Thetford, Owen Gordon (1958). Aircraft of the Royal Air Force 1918–58 (1st ed.). London: Putnam. OCLC 753002715.

Further reading

[edit]- Hillman, Jo; Higgs, Colin (2020). Supermarine Southampton: The Flying Boat that Made R.J. Mitchell. Air World. ISBN 978-15267-8-497-1.

- Lipscombe, Trevor (2018). "RAF Far East Flight: Part 1: UK–Singapore". The Aviation Historian. No. 25. pp. 76–88. ISSN 2051-1930.

- Pegram, Ralph (2016). Beyond the Spitfire: The Unseen Designs of R.J. Mitchell. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6515-6.

- Shelton, John (2008). Schneider Trophy to Spitfire – The Design Career of R.J. Mitchell (Hardback). Sparkford: Hayes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84425-530-6.

- Spooner, Stanley, ed. (18 November 1926). "The Supermarine "Southampton"". Flight. pp. 744–747. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Spooner, Stanley, ed. (25 November 1926). "The Supermarine "Southampton"". Flight. pp. 759–764. ISSN 0015-3710.

External links

[edit]- Flying boats visit Plymouth: Film made in 1927 of the RAF Far East Flight's four Supermarine Southamptons landing at Plymouth from Felixstowe en route to Australia and Singapore, from the British Film Institute