User:Jhingla Singh/sandbox

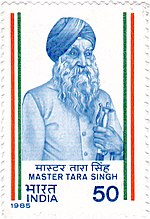

Master Tara Singh | |

|---|---|

Master Tara Singh, October 1947 | |

| Born | Nanak Chand Malhotra 24 June 1885[1] |

| Died | 22 November 1967 (aged 82)[1] |

| Resting place | Kiratpur Sahib |

| Monuments | Jang-e-Azaadi Museum, Kartarpur |

| Nationality | British Indian, Indian |

| Other names | Master Rawalpindi |

| Occupation(s) | Leader, author, poet, soldier, general. |

| Known for | Sikh nationalism. |

| Notable work | He wrote the novels:

Betrayal of Sikh Nation He edited the newspapers: Akali (Urdu)Akali Te Pardesi |

| Political party | Shiromani Akali Dal |

| Opponent(s) | Pakistan British Raj India Sant Fateh Singh |

| Criminal charges | Illegal Protests (1930-1966) |

| Criminal penalty | Jailed 14 times 4 times for the Non-Cooperation Movement 2 times for the Salt March 8 times for the Punjabi Suba movement |

| Spouse | Tej Kaur |

| Children | Rajinder Kaur |

| Parent(s) | Moolan Devi (mother) Bakshi Gopi Chand (father) |

Master Tara Singh (24 June 1885 – 22 November 1967) was a Punjabi Sikh political and religious figure in the first half of the 20th century. He was instrumental in organising the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee and guiding the Sikhs during the partition of Punjab, which he strongly opposed.[2] He advocated for the Punjab region as a homeland for the Sikhs.[3]

Early life[edit]

Singh was born on 24 June 1885 in Rawalpindi, Punjab Province in British India into a Malhotra Khatri family.[4][5] Later he became a high school teacher upon his graduation from Khalsa College, Amritsar, in 1907. Singh's career in education was within the Sikh school system and the use of "Master" as a prefix to his name reflects this period.[1]

Political career[edit]

Singh was ardent in his desire to promote and protect the cause of Sikhism. This often put him at odds with civil authorities and he was jailed on 14 occasions for civil disobedience between 1930 and 1966. Early examples of his support for civil disobedience came through his close involvement with the movement led by Mahatma Gandhi. He became a leader of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) political party, which was the major force in Sikh politics, and he was similarly involved with the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (Supreme Committee of Gurdwara Management), an apex body that dealt with the Sikh places of worship known as gurdwaras.[1]

He was instrumental in getting the Sikh State resolution passed by Akali Dal under his leadership in 1946, which declared Punjab as the natural homeland of the Sikhs.[6] He later led their demand for a Sikh-majority state in East Punjab. A devout worker for the cause of Sikh religious and political integrity, Tara Singh often found himself in opposition to Indian Government. He was jailed for civil disobedience 14 times between 1930 and 1966.[7] In the 2020 biography of former Punjab CM Partap Singh Kairon, it has been documented that Tara Singh revived his demand for a separate nation for Sikhs after Independence.[8] In 2018, his granddaughter in law mentioned that Master Tara Singh’s “dream of an autonomous Sikh state in India remains unfulfilled.[9]”

Partition of India[edit]

As with other Sikh organisations, Singh and his Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) condemned the Lahore Resolution and the movement to create Pakistan, viewing it as welcoming possible persecution; he thus strongly opposed the partition of Punjab, saying that he and his party would fight "tooth and nail" against the concept of a Pakistan.[2]

Independent India[edit]

Singh's most significant cause was the creation of a distinct Punjabi-speaking state. He believed that this would best protect the integrity of Sikh religious and political traditions. He began a hunger strike in 1961 at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, promising to continue it to his death unless the then Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru agreed to his demand for such a state. Nehru argued that India was a secular country and the creation of a state based on religious distinction was inappropriate. Nonetheless, Nehru did promise to consider the issue. Singh abandoned his fast after 48 days. Singh's fellow Sikhs turned against him, believing that he had capitulated, and they put him on trial in a court adjudged by pijaras. Singh pleaded guilty to the charges laid against him and found his reputation in tatters. The community felt he had abandoned his ideals and replaced him in the SAD.[1]

The linguistic division of the Indian state of Punjab eventually took place in 1966, with Hindu majority, Hindi-speaking areas redesignated as a part of the state of Haryana and Himachal, whilst Punjab became a Sikh majority, Punjabi speaking state. Singh himself died in Chandigarh on 22 November 1967.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g "Tara Singh". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ a b Kudaisya, Gyanesh; Yong, Tan Tai (2004). The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-134-44048-1.

No sooner was it made public than the Sikhs launched a virulent campaign against the Lahore Resolution. Pakistan was portrayed as a possible return to an unhappy past when Sikhs were persecuted and Muslims the persecutor. Public speeches by various Sikh political leaders on the subject of Pakistan invariably raised images of atrocities committed by Muslims on Sikhs and of the martyrdom of their gurus and heroes. Reactions to the Lahore Resolution were uniformly negative and Sikh leaders of all political persuasions made it clear that Pakistan would be 'wholeheartedly resisted'. The Shiromani Akali Dal, the party with a substantial following amongst the rural Sikhs, organized several well-attended conferences in Lahore to condemn the Muslim League. Singh, leader of the Akali Dal, declared that his party would fight Pakistan 'tooth and nail'. Not be outdone, other Sikh political organizations, rival to the Akali Dal, namely the Central Khalsa Young Men Union and the moderate and loyalist Chief Khalsa Dewan, declared in equally strong language their unequivocal opposition to the Pakistan scheme.

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/book/3615/chapter-abstract/144931833?redirectedFrom=fulltext. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Tambiah, Stanley J. (3 January 1997). Leveling Crowds: Ethnonationalist Conflicts and Collective Violence in South Asia. University of California Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-520-91819-1.

- ^ "Ranjit Singh's statue unveiled in Parliament House". The Tribune (Chandigarh). 21 August 2003.

- ^ "Looking back at the Khalistani movement". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/book/3615/chapter-abstract/144938763?redirectedFrom=fulltext. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/kairon-gave-precedence-to-region-over-religion-496212?_gl=1*nkudso*_ga*YW1wLTlOZF81Y29fY1YzVUluRW9KQlplS1E.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Master Tara Singh's dream of autonomous Sikh state remained unfilled, says granddaughter-in-law". Hindustan Times. 24 June 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Gateway to Sikhism: Famous Sikhs:Master Tara Singh

- Heritage of the Sikhs, by Sardar Harbans Singh

- The Sikh Times - Biographies - Master Tara Singh: India Finally Pays Tribute

- Bhai Maharaj Singh Ji

- The Punjab Heritage THE STRUGGLE FOR KHALISTAN

- Harjinder Singh Dilgeer, SIKH TWAREEKH (Sikh History in Punjabi in 5 volumes), Sikh University Press, Belgium, 2007.

- Harjinder Singh Dilgeer, SIKH HISTORY (in English in 10 volumes), Sikh University Press, Belgium, 2010–11.

- Harjinder Singh Dilgeer, Master Tara Singh's Contribution to Punjabi Literature (thesis, granted Ph.D. by the Panjab University in 1982).

- Durlab Singh, Valiant Fighter. 1945.

- Manohar Singh Batra, Master Tara Singh, Delhi, 1972.

- Jaswant Singh, Jeewan Master Tara Singh, Amritsar, 1972.

- Master Tara Singh, Meri Yaad, Amritsar, 1945

External links[edit]

- 1885 births

- 1967 deaths

- Politicians from Rawalpindi

- Sikh politics

- Indian Sikhs

- Punjabi people

- Chandigarh politicians

- Indian former Hindus

- Converts to Sikhism from Hinduism

- Shiromani Akali Dal politicians

- Indian independence activists from Punjab (British India)

- Prisoners and detainees of British India

- 19th-century Indian people

- 19th-century Hindus

- 20th-century Indian politicians