Value-added tax

It has been suggested that Value Added Tax in Bangladesh and Value added taxation in Bangladesh be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2017. |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

A value-added tax (VAT), known in some countries as a goods and services tax (GST), is a type of general consumption tax that is collected incrementally, based on the surplus value, added to the price on the work at each stage of production, which is usually implemented as a destination-based tax, where the tax rate is based on the location of the customer. VATs raise about a fifth of total tax revenues both worldwide and among the members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).[1]: 14 As of 2014, 160 of the world's approximately 193 countries employ a VAT, including all OECD members except the United States,[1]: 14 which uses a sales tax system instead.

There are two main methods of calculating VAT: the credit-invoice or invoice-based method, and the subtraction or accounts-based method. Using the credit-invoice method, sales transactions are taxed, with the customer informed of the VAT on the transaction, and businesses may receive a credit for VAT paid on input materials and services. The credit-invoice method is the most widely employed method, used by all national VATs except for Japan. Using the subtraction method, at the end of a reporting period, a business calculates the value of all taxable sales then subtracts the sum of all taxable purchases and the VAT rate is applied to the difference. The subtraction method VAT is currently only used by Japan, although subtraction method VATs, often using the name "flat tax", have been part of many recent tax reform proposals by US politicians.[2][3][4] With both methods, there are exceptions in the calculation method for certain goods and transactions, created for either pragmatic collection reasons or to counter tax fraud and evasion.

History

Germany and France were the first countries to implement VAT, doing so in the form of a general consumption tax during World War I.[5] The modern variation of VAT was first implemented by France in the 1950s.[5]

Overview

The amount of VAT is decided by the state as percentage of the end-market price. As its name suggests, value-added tax is designed to tax only the value added by a business on top of the services and goods it can purchase from the market.

To understand what this means, consider a production process (e.g., take-away coffee starting from coffee beans) where products get successively more valuable at each stage of the process. When an end-consumer makes a purchase, they are not only paying for the VAT for the product at hand (e.g., a cup of coffee), but in effect, the VAT for the entire production process (e.g., the purchase of the coffee beans, their transportation, processing, cultivation, etc.), since VAT is always included in the prices.

The value-added effect is achieved by prohibiting end-consumers to recover VAT on purchases, but permitting businesses to do so. The VAT collected by the state is computed as the difference between the VAT of sales earnings and the VAT of those goods and services upon which the product depends. The difference is the tax due to the value added by the business. In this way, the total tax levied at each stage in the economic chain of supply is a constant fraction.

History

Germany and France were the first countries to implement VAT, doing so in the form of a general consumption tax during World War I.[5] The modern variation of the VAT was first introduced by France in the 1950s.[5] Maurice Lauré, Joint Director of the France Tax Authority, the Direction Générale des Impôts implemented the VAT on 10 April 1954, although German industrialist Dr. Wilhelm von Siemens proposed the concept in 1918. Initially directed at large businesses, it was extended over time to include all business sectors. In France, it is the most important source of state finance, accounting for nearly 50% of state revenues.[6]

A 2017 study found that the adoption of VAT is strongly linked to countries with corporatist institutions.[5]

Implementation

The standard way to implement a value-added tax involves assuming a business owes some fraction on the price of the product minus all taxes previously paid on the good.

By the method of collection, VAT can be accounts-based or invoice-based.[7] Under the invoice method of collection, each seller charges VAT rate on his output and passes the buyer a special invoice that indicates the amount of tax charged. Buyers who are subject to VAT on their own sales (output tax), consider the tax on the purchase invoices as input tax and can deduct the sum from their own VAT liability. The difference between output tax and input tax is paid to the government (or a refund is claimed, in the case of negative liability). Under the accounts based method, no such specific invoices are used. Instead, the tax is calculated on the value added, measured as a difference between revenues and allowable purchases. Most countries today use the invoice method, the only exception being Japan, which uses the accounts method.

By the timing of collection,[8] VAT (as well as accounting in general) can be either accrual or cash based. Cash basis accounting is a very simple form of accounting. When a payment is received for the sale of goods or services, a deposit is made, and the revenue is recorded as of the date of the receipt of funds—no matter when the sale had been made. Cheques are written when funds are available to pay bills, and the expense is recorded as of the cheque date—regardless of when the expense had been incurred. The primary focus is on the amount of cash in the bank, and the secondary focus is on making sure all bills are paid. Little effort is made to match revenues to the time period in which they are earned, or to match expenses to the time period in which they are incurred. Accrual basis accounting matches revenues to the time period in which they are earned and matches expenses to the time period in which they are incurred. While it is more complex than cash basis accounting, it provides much more information about your business. The accrual basis allows you to track receivables (amounts due from customers on credit sales) and payables (amounts due to vendors on credit purchases). The accrual basis allows you to match revenues to the expenses incurred in earning them, giving you more meaningful financial reports.

Registration

In general, countries that have a VAT system requires some businesses to be registered for VAT purposes. VAT registered businesses can be natural persons or legal entities, but countries have different thresholds or regulations specifying at which turnover levels registration becomes compulsory. Businesses that are VAT registered are obliged to include VAT on goods and services that they supply to others (with some exceptions, which vary by country) and account for the VAT to the taxing authority. VAT-registered businesses are entitled to a VAT deduction for the VAT they pay on the goods and services they acquire from other VAT-registered businesses.

Comparison with sales tax

Value-added tax avoids the cascade effect of sales tax by taxing only the value added at each stage of production. For this reason, throughout the world, VAT has been gaining favor over traditional sales taxes. In principle, VAT applies to all provisions of goods and services. VAT is assessed and collected on the value of goods or services that have been provided every time there is a transaction (sale/purchase). The seller charges VAT to the buyer, and the seller pays this VAT to the government. If, however, the purchasers are not the end users, but the goods or services purchased are costs to their business, the tax they have paid for such purchases can be deducted from the tax they charge to their customers. The government only receives the difference; in other words, it is paid tax on the gross margin of each transaction, by each participant in the sales chain.

In many developing countries such as India, sales tax/VAT are key revenue sources as high unemployment and low per capita income render other income sources inadequate. However, there is strong opposition to this by many sub-national governments as it leads to an overall reduction in the revenue they collect as well as of some autonomy.

In theory, sales tax is normally charged on end users (consumers). The VAT mechanism means that the end-user tax is the same as it would be with a sales tax. The main disadvantage of VAT is the extra accounting required by those in the middle of the supply chain; this is balanced by the simplicity of not requiring a set of rules to determine who is and is not considered an end user. When the VAT system has few, if any, exemptions such as with GST in New Zealand, payment of VAT is even simpler.

A general economic idea is that if sales taxes are high enough, people start engaging in widespread tax evading activity (like buying over the Internet, pretending to be a business, buying at wholesale, buying products through an employer etc.). On the other hand, total VAT rates can rise above 10% without widespread evasion because of the novel collection mechanism.[9] However, because of its particular mechanism of collection, VAT becomes quite easily the target of specific frauds like carousel fraud, which can be very expensive in terms of loss of tax incomes for states.

Examples

Consider the manufacture and sale of any item, which in this case we will call a widget. In what follows, the term "gross margin" is used rather than "profit". Profit is the remainder of what is left after paying other costs, such as rent and personnel costs.

Without any tax

- A widget manufacturer, for example, spends $1.00 on raw materials and uses them to make a widget.

- The widget is sold wholesale to a widget retailer for $1.20, leaving a gross margin of $0.20.

- The widget retailer then sells the widget to a widget consumer for $1.50, leaving a gross margin of $0.30.

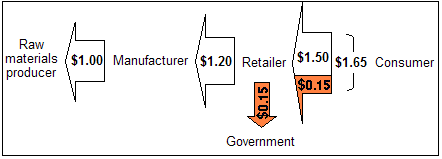

With a sales tax

With a 10% sales tax:

- The manufacturer spends $1.00 for the raw materials, certifying it is not a final consumer.

- The manufacturer charges the retailer $1.20, checking that the retailer is not a consumer, leaving the same gross margin of $0.20.

- The retailer charges the consumer ($1.50 x 1.10) = $1.65 and pays the government $0.15, leaving the gross margin of $0.30.

So the consumer has paid 10% ($0.15) extra, compared to the no taxation scheme, and the government has collected this amount in taxation. The retailers have not paid any tax directly (it is the consumer who has paid the tax), but the retailer has to do the paperwork in order to correctly pass on to the government the sales tax it has collected. Suppliers and manufacturers have the administrative burden of supplying correct state exemption certifications, and checking that their customers (retailers) are not consumers. The retailer must verify and maintain these exemption certificate. In addition, the retailer must keep track of what is taxable and what is not along with the various tax rates in each of the cities, counties and states for the 35,000 plus various taxing jurisdictions.

A large exception to this state of affairs is online sales. Typically if the online retail firm has no nexus (also known as substantial physical presence) in the state where the merchandise will be delivered, no obligation is imposed upon the retailer to collect sales taxes from "out-of-state" purchasers. Generally, state law requires that the purchaser report such purchases to the state taxing authority and pay the use tax, which compensates for the sales tax that is not paid by the retailer.

With a value-added tax

With a 10% VAT:

- The manufacturer spends ($1 x 1.10) = $1.10 for the raw materials, and the seller of the raw materials pays the government $0.10.

- The manufacturer charges the retailer ($1.20 x 1.10) = $1.32 and pays the government ($0.12 minus $0.10) = $0.02, leaving the same gross margin of ($1.32 – $1.10 – $0.02) = $0.20.

- The retailer charges the consumer ($1.50 x 1.10) = $1.65 and pays the government ($0.15 minus $0.12) = $0.03, leaving the same gross margin of ($1.65 – $1.32 – $0.03) = $0.30.

- The manufacturer and retailer realize less gross margin from a percentage perspective. If the cost of raw material production were shown, this would also be true of the raw material supplier's gross margin on a percentage basis.

- Note that the taxes paid by both the manufacturer and the retailer to the government are 10% of the values added by their respective business practices (e.g. the value added by the manufacturer is $1.20 minus $1.00, thus the tax payable by the manufacturer is ($1.20 – $1.00) × 10% = $0.02).

With VAT, the consumer has paid, and the government received, the same dollar amount as with a sales tax. The businesses have not incurred any tax themselves. Their obligation is limited to assuming the necessary paperwork in order to pass on to the government the difference between what they collect in VAT (output tax, an 11th of their sales) and what they spend in VAT (input VAT, an 11th of their expenditure on goods and services subject to VAT). However they are freed from any obligation to request certifications from purchasers who are not end users, and of providing such certifications to their suppliers.

On the other hand, they incur increased accounting costs for collecting the tax, which are not reimbursed by the taxing authority. For example, wholesale companies now have to hire staff and accountants to handle the VAT paperwork, which would not be required if they were collecting sales tax instead.

The advantage of the VAT system over the sales tax system is that under sales tax, the seller has no incentive to disbelieve a purchaser who says it is not a final user. That is to say the payer of the tax has no incentive to collect the tax. Under VAT, all sellers collect tax and pay it to the government. A purchaser has an incentive to deduct input VAT, but must prove it has the right to do so, which is usually achieved by holding an invoice quoting the VAT paid on the purchase, and indicating the VAT registration number of the supplier.

Limitations to the examples

In the above examples, we assumed that the same number of widgets were made and sold both before and after the introduction of the tax. This is not true in real life.

The supply and demand economic model suggests that any tax raises the cost of transaction for someone, whether it is the seller or purchaser. In raising the cost, either the demand curve shifts leftward, or the supply curve shifts upward. The two are functionally equivalent. Consequently, the quantity of a good purchased decreases, and/or the price for which it is sold increases.

This shift in supply and demand is not incorporated into the above example, for simplicity and because these effects are different for every type of good. The above example assumes the tax is non-distortionary.

Limitations of VAT

A VAT, like most taxes, distorts what would have happened without it. Because the price for someone rises, the quantity of goods traded decreases. Correspondingly, some people are worse off by more than the government is made better off by tax income. That is, more is lost due to supply and demand shifts than is gained in tax. This is known as a deadweight loss. If the income lost by the economy is greater than the government's income; the tax is inefficient. It must be noted that a VAT and a Non-VAT have the same implications on the microeconomic model.

The entire amount of the government's income (the tax revenue) may not be a deadweight drag, if the tax revenue is used for productive spending or has positive externalities – in other words, governments may do more than simply consume the tax income. While distortions occur, consumption taxes like VAT are often considered superior because they distort incentives to invest, save and work less than most other types of taxation – in other words, a VAT discourages consumption rather than production.

In the diagram on the right:

- Deadweight loss: the area of the triangle formed by the tax income box, the original supply curve, and the demand curve

- Governments tax income: the grey rectangle that says "tax revenue"

- Total consumer surplus after the shift: the green area

- Total producer surplus after the shift: the yellow area

Imports and exports

Being a consumption tax, VAT is usually used as a replacement for sales tax. Ultimately, it taxes the same people and businesses the same amounts of money, despite its internal mechanism being different. There is a significant difference between VAT and Sales Tax for goods that are imported and exported:

- VAT is charged for a commodity that is exported while sales tax is not.

- Sales tax is paid for the full price of the imported commodity, while VAT is expected to be charged only for value added to this commodity by the importer and the reseller.

This means that, without special measures, goods will be taxed twice if they are exported from one country that does have VAT to another country that has sales tax instead. Conversely, goods that are imported from a VAT-free country into another country with VAT will result in no sales tax and only a fraction of the usual VAT. There are also significant differences in taxation for goods that are being imported / exported between countries with different systems or rates of VAT. Sales tax does not have those problems – it is charged in the same way for both imported and domestic goods, and it is never charged twice.

To fix this problem, nearly all countries that use VAT use special rules for imported and exported goods:

- All imported goods are charged VAT tax for their full price when they are sold for the first time.

- All exported goods are exempted from any VAT payments.

For these reasons VAT on imports and VAT rebates on exports form a common practice approved by the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Example

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (October 2013) |

Consider a Ford car that cost $25,000 to produce in the USA (that does not have a VAT, but does have 10% Sales Tax) and an Opel car that costs $25,000 to produce in Germany (that does have 20% VAT). Both prices are shown with all taxes imposed on manufacturers of these cars, including social taxes, income taxes, etc., but without taxes imposed on consumers – that is, sales tax in USA and VAT in Germany.

Without a special modification related to Export / Import, customer prices will be

| Cost to Produce | Price paid for Ford

by consumer |

Price paid for Opel

by Consumer |

Taxes paid for Ford

by consumer |

Taxes paid for Opel

by consumer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the USA | $25,000 | $27,500 | $33,000 | $2,500 (10% sales tax only) | $8,000 (Original 20% VAT already on import & later 10% sales tax at retail) |

| In Germany | $25,000 | $25,000 | $30,000 | $0 (No sales tax in Germany) | $5,000 (VAT) |

Note that Opel prices appear to be inherently higher than Ford ones. A common mistake in a lot of examples trying to prove that VAT rebates form as a trade barrier is, to set retail prices equal for both Ford and Opel. This way, prices are initially equal, but become different after all the additional VAT taxes and rebates described below. Such an approach does not take into account the simple fact that Opel prices in the table above always include VAT while Ford prices never include it. That's exactly why additional adjustments are made in VAT taxation.

One may try to object that this simply means that Germany has generally higher taxes but, in fact, this is not the case for consumer taxes. Consider a hypothetical situation where consumer tax remains exactly the same in Germany as in the example above, but now it is collected as 20% Sales Tax:

| Price paid for Ford by consumer |

Price paid for Opel by consumer |

Taxes paid for Ford by consumer |

Taxes paid for Opel by consumer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the USA | $27,500 | $27,500 | $2,500 (sales tax only) | $2,500 (sales tax only) |

| In Germany | $30,000 | $30,000 | $5,000 (sales tax only) | $5,000 (sales tax only) |

Now lets use the same assumption that the end price to the consumer remains $25,000 and there are no taxes. All goods would be sold for $25,000 and no manufacturer has an advantage:

| Price paid for Ford by consumer |

Price paid for Opel by consumer |

Taxes paid for Ford by consumer |

Taxes paid for Opel by consumer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the USA | $25,000 | $25,000 | $0 (No tax) | $0 (No tax) |

| In Germany | $25,000 | $25,000 | $0 (No Tax) | $0 (No Tax) |

Indeed, the end price to the consumer is $25,000 in all instances.

Once again, assuming that the end price to the consumer is $25,000, consider a hypothetical situation where consumer tax remains 10% in the United States, Germany imposes a 20% VAT on imported US goods, rebates its 20% VAT on goods exported to the US, and the US charges a 10% sales tax on both goods:

| Price paid for Ford by consumer |

Price paid for Opel by consumer |

Taxes paid for Ford by consumer |

Taxes paid for Opel by consumer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the USA | $27,500 | $27,500 | $2,500 (sales tax only) | $2,500 (sales tax only) |

| In Germany | $30,000 | $30,000 | $5,000 (VAT tax only) | $5,000 (end price to consumer) |

Even in the case in which a country with a VAT remits exports, price distortions do not occur. A U.S. producer exporting a car to Germany will not be charged the U.S. sales tax, but will be charged the VAT. Since a German domestic producer will also be charged a VAT, both companies are on equal footing in Germany. Similarly, a U.S. company selling a car domestically will be charged a sales tax as will the German manufacturer attempting to sell in the U.S. However, if Germany did not remit the VAT on export, the German producer would be charged both the sales tax and the VAT tax, thus facing a price distortion. The usage of VAT remittance on exports helps ensure that export price distortion does not occur.[10]

Different systems

Australia

The goods and services tax (GST) is a value-added tax introduced in Australia in 2000, which is collected by the Australian Tax Office. The revenue is then redistributed to the states and territories via the Commonwealth Grants Commission process. In essence, this is Australia's program of horizontal fiscal equalisation. Whilst the rate is currently set at 10%, there are many domestically consumed items that are effectively zero-rated (GST-free) such as fresh food, education, and health services, certain medical products, as well as exemptions for Government charges and fees that are themselves in the nature of taxes.

Bangladesh

Value-added tax in Bangladesh was introduced in 1991 replacing Sales Tax and most of Excise Duties. The Value Added Tax Act, 1991 was enacted that year and VAT started its passage from 10 July 1991. The 10 July is observed as National VAT Day in Bangladesh.

Within the passage of 25 years, VAT has become the largest source of Government Revenue. About 56% of total tax revenue is VAT revenue in Bangladesh.

Standard VAT rate is 15%. Export is Zero rated. Besides these rates, there are several reduced rates locally called Truncated Rate for service sectors that are available. Different rates for different services are applied. Truncated Rates are 1.5%, 2.25%, 2.5%, 3%, 4%, 4.5%, 5%, 5.5%, 6%, 7.5%, 9% and 10%.

Bangladesh VAT is characterized by many distortions, i.e., value declaration for product and service, branch registration, tariff value, truncated rates, many restriction on credit system, lump-sum VAT (package VAT) advance payment of VAT, excessive exemption etc. For many distortion, VAT-GDP ratio is about 4% here. To increase productivity of VAT, Government has enacted the Value Added Tax and Supplementary Duty Act of 2012. This law will be in operation from 1 July 2017 with an automated administration.

National Board of Revenue 1 is the apex organization administering the Value Added Tax.

Canada

Goods and Services Tax (GST) is a value-added tax introduced by the Federal Government in 1991 at a rate of 7%, later reduced to the current rate of 5%. A Harmonized Sales Tax (HST; combined GST and provincial sales tax) is collected in New Brunswick (15%), Newfoundland (13%), Nova Scotia (15%), Ontario (13%), Prince Edward Island (15%), and, for a short time until 2013, British Columbia (12%). (Quebec has a de facto 14.975% HST: its provincial sales tax follows the same rules as the GST, and both are collected together by Revenu Québec.) Advertised and posted prices generally exclude taxes, which are calculated at time of payment; common exceptions are motor fuels, the posted prices for which include sales and excise taxes, and items in vending machines as well as alcohol in monopoly stores. Basic groceries, prescription drugs, inward/outbound transportation and medical devices are exempt.

China

VAT was implemented in China in 1984 and is administered by the State Administration of Taxation. In 2007, the revenue from VAT was 15.47 billion yuan ($2.2 billion) which made up 33.9 percent of China's total tax revenue for the year. The standard rate of VAT in China is 17%. There is a reduced rate of 13% that applies to products such as books and types of oils.[11][citation needed]

European Union

The European Union value added tax (EU VAT) is a value-added tax encompassing member states in the European Union VAT area. Joining in this is compulsory for member states of the European Union. As a consumption tax, the EU VAT taxes the consumption of goods and services in the EU VAT area. The EU VAT's key issue asks where the supply and consumption occurs thereby determining which member state will collect the VAT and which VAT rate will be charged.

Each Member State's national VAT legislation must comply with the provisions of EU VAT law as set out in Directive 2006/112/EC. This Directive sets out the basic framework for EU VAT, but does allow Member States some degree of flexibility in implementation of VAT legislation. For example, different rates of VAT are allowed in different EU member states. However Directive 2006/112 requires Member States to have a minimum standard rate of VAT of 15% and one or two reduced rates not to be below 5%. Some Member States have a 0% VAT rate on certain supplies; these Member States would have agreed this as part of their EU Accession Treaty (for example, newspapers and certain magazines in Belgium). The highest rate currently in operation in the EU is 27% (Hungary), though Member States are free to set higher rates. There is, in fact only one Member State (Denmark) that does not have a reduced rate of VAT.[12]

There are some areas of member state which have lower standard VAT rate than the 15% limit or have zero VAT. Such areas are excluded from the EU VAT rules, and sales from them to normal parts of the EU are considered import for VAT purposes.

VAT that is charged by a business and paid by its customers is known as "output VAT" (that is, VAT on its output supplies). VAT that is paid by a business to other businesses on the supplies that it receives is known as "input VAT" (that is, VAT on its input supplies). A business is generally able to recover input VAT to the extent that the input VAT is attributable to (that is, used to make) its taxable outputs. Input VAT is recovered by setting it against the output VAT for which the business is required to account to the government, or, if there is an excess, by claiming a repayment from the government. Private people are generally allowed to buy goods in any member country and bring it home and pay only the VAT to the seller.

The VAT Directive (prior to 1 January 2007 referred to as the Sixth VAT Directive) requires certain goods and services to be exempt from VAT (for example, postal services, medical care, lending, insurance, betting), and certain other goods and services to be exempt from VAT but subject to the ability of an EU member state to opt to charge VAT on those supplies (such as land and certain financial services). Input VAT that is attributable to exempt supplies is not recoverable, although a business can increase its prices so the customer effectively bears the cost of the 'sticking' VAT (the effective rate will be lower than the headline rate and depend on the balance between previously taxed input and labour at the exempt stage).

Gulf Cooperation Council

Increased growth and pressure on the GCC's governments to provide infrastructure to support growing urban centers, the Member States of the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC), which together make up the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC), have felt the need to introduce a tax system in the region.

In particular, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) plans, on 1 January 2018, to implement VAT. For companies whose annual revenues exceed $1m (Dh3.75m), registration will be mandatory. Oman’s Minister of Financial Affairs indicated that GCC countries have agreed the introductory rate of VAT will be 5%.

India

VAT was introduced into the Indian taxation system from 1 April 2005. Of the then 28 Indian states, eight did not introduce VAT at first instance including five states ruled by BJP. There is uniform VAT rate of 5% and 14.5% all over India. The government of Tamil Nadu introduced an act by the name Tamil Nadu Value Added Tax Act 2006 which came into effect from the 1 January 2007. It was also known as the TN-VAT. Under the Narendra Modi government, a new national Goods and Services Tax was introduced under the One Hundred and First Amendment of the Constitution of India.

Malaysia

The goods and services tax (GST) is a value-added tax introduced in Malaysia in 2015, which is collected by the Royal Malaysian Customs Department. Whilst the rate is currently set at 6%, there are many domestically consumed items that are effectively zero-rated (GST-free) such as fresh foods, education, health services and medicines.

Mexico

Value-added tax (Template:Lang-es, IVA) is a tax applied in Mexico and other countries of Latin America. In Chile, it is also called Impuesto al Valor Agregado and, in Peru, it is called Impuesto General a las Ventas or IGV.

Prior to the IVA, a sales tax (Template:Lang-es) had been applied in Mexico. In September 1966, the first attempt to apply the IVA took place when revenue experts declared that the IVA should be a modern equivalent of the sales tax as it occurred in France. At the convention of the Inter-American Center of Revenue Administrators in April and May 1967, the Mexican representation declared that the application of a value-added tax would not be possible in Mexico at the time. In November 1967, other experts declared that although this is one of the most equitable indirect taxes, its application in Mexico could not take place.

In response to these statements, direct sampling of members in the private sector took place as well as field trips to European countries where this tax was applied or soon to be applied. In 1969, the first attempt to substitute the mercantile-revenue tax for the value-added tax took place. On 29 December 1978 the Federal government published the official application of the tax beginning on 1 January 1980 in the Official Journal of the Federation.

As of 2010, the general VAT rate was 16%. This rate was applied all over Mexico except for bordering regions (i.e. the United States border, or Belize and Guatemala), where the rate was 11%. The main exemptions are for books, food, and medicines on a 0% basis. Also some services are exempt like a doctor's medical attention. In 2014 Mexico Tax Reforms eliminated the favorable tax rate for border regions and increased the VAT to 16% across the country.

Nepal

VAT was implemented in 1998 and is the major source of government revenue. It is administered by Inland Revenue Department of Nepal. Nepal has been levying two rates of VAT: Normal 13% and zero rate. In addition, some goods and services are exempt from VAT.

New Zealand

The goods and services tax (GST) is a value-added tax that was introduced in New Zealand in 1986, currently levied at 15%. It is notable for exempting few items from the tax. From July 1989 to September 2010, GST was levied at 12.5%, and prior to that at 10%.

The Nordic countries

MOMS (Template:Lang-da, formerly meromsætningsafgift), Template:Lang-no (bokmål) or meirverdiavgift (nynorsk) (abbreviated MVA), Template:Lang-sv (until the early 1970s labeled as OMS OMSättningsskatt only), Template:Lang-is (abbreviated VSK), Template:Lang-fo (abbreviated MVG) or Finnish: arvonlisävero (abbreviated ALV) are the Nordic terms for VAT. Like other countries' sales and VAT taxes, it is an indirect tax.

| Year | Tax level (Denmark) | Name |

| 1962 | 9% | OMS |

| 1967 | 10% | MOMS |

| 1968 | 12.5658 | |

| 1970 | 15% | MOMS |

| 1977 | 18% | MOMS |

| 1978 | 20.25% | MOMS |

| 1980 | 22% | MOMS |

| 1992 | 25% | MOMS |

In Denmark, VAT is generally applied at one rate, and with few exceptions is not split into two or more rates as in other countries (e.g. Germany), where reduced rates apply to essential goods such as foodstuffs. The current standard rate of VAT in Denmark is 25%. That makes Denmark one of the countries with the highest value-added tax, alongside Norway, Sweden and Croatia. A number of services have reduced VAT, for instance public transportation of private persons, health care services, publishing newspapers, rent of premises (the lessor can, though, voluntarily register as VAT payer, except for residential premises), and travel agency operations.

In Finland, the standard rate of VAT is 24% as of 1 January 2013 (raised from previous 23%), along with all other VAT rates, excluding the zero rate.[16] In addition, two reduced rates are in use: 14% (up from previous 13% starting 1 January 2013), which is applied on food and animal feed, and 10%, (increased from 9% 1 January 2013) which is applied on passenger transportation services, cinema performances, physical exercise services, books, pharmaceuticals, entrance fees to commercial cultural and entertainment events and facilities. Supplies of some goods and services are exempt under the conditions defined in the Finnish VAT Act: hospital and medical care; social welfare services; educational, financial and insurance services; lotteries and money games; transactions concerning bank notes and coins used as legal tender; real property including building land; certain transactions carried out by blind persons and interpretation services for deaf persons. The seller of these tax-exempt services or goods is not subject to VAT and does not pay tax on sales. Such sellers therefore may not deduct VAT included in the purchase prices of his inputs. Åland, an autonomous area, is considered to be outside the EU VAT area, even if its VAT rate is the same as for Finland. Goods brought from Åland to Finland or other EU countries is considered to be export/import. This enables tax free sales onboard passenger ships.

In Iceland, VAT is split into two levels: 24% for most goods and services but 11% for certain goods and services. The 11% level is applied for hotel and guesthouse stays, licence fees for radio stations (namely RÚV), newspapers and magazines, books; hot water, electricity and oil for heating houses, food for human consumption (but not alcoholic beverages), access to toll roads and music.[17]

In Norway, VAT is split into three levels: 25% general rate, 15% on foodstuffs and 10% on the supply of passenger transport services and the procurement of such services, on the letting of hotel rooms and holiday homes, and on transport services regarding the ferrying of vehicles as part of the domestic road network. The same rate applies to cinema tickets and to the television licence.[18] Financial services, health services, social services and educational services are all outside the scope of the VAT Act.[19] Newspapers, books and periodicals are zero-rated.[20] Svalbard has no VAT because of a clause in the Svalbard Treaty.

In Sweden, VAT is split into three levels: 25% for most goods and services, 12% for foods including restaurants bills and hotel stays and 6% for printed matter, cultural services, and transport of private persons. Some services are not taxable for example education of children and adults if public utility, and health and dental care, but education is taxable at 25% in case of courses for adults at a private school. Dance events (for the guests) have 25%, concerts and stage shows have 6%, and some types of cultural events have 0%.

MOMS replaced OMS (Danish "omsætningsafgift", Swedish "omsättningsskatt") in 1967, which was a tax applied exclusively for retailers.

Trinidad and Tobago

Value-added tax (VAT) in T&T is currently 12.5% as of February 1, 2016. Before that date VAT used to be at 15%.

Ukraine

In Ukraine, the revenue to state budget from VAT is the most significant. By Ukraine tax code, there are 3 VAT tax rates in Ukraine[21]: 20% (general tax rate; applied to most goods and services), 7% (special tax rate; applied mostly to medicines and medical products import and trade operations) and 0% (special tax rate; applied mostly to export of goods and services, international transport of passengers, baggage and cargo).

Vietnam

Value-added tax (VAT) in Vietnam is a broadly based consumption tax assessed on the value added to goods and services arising through the process of production, circulation, and consumption. It's an indirect tax in Vietnam on domestic consumption applied nationwide rather than at different levels such as state, provincial or local taxes. It is a multi-stage tax which is collected at every stage of the production and distribution chain and passed on to the final customer. It is applicable to the majority of goods and services bought and sold for use in the country. Goods that are sold for export and services that are sold to customers abroad are normally not subject to VAT.[citation needed]

All organizations and individuals producing and trading VAT taxable goods and services in Vietnam have to pay VAT, regardless of whether they have Vietnam-based resident establishments or not.

Vietnam has three VAT rates: 0 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent. 10 percent is the standard rate applied to most goods and services unless otherwise stipulated.

A variety of goods and service transactions may qualify for VAT exemption.[citation needed]

United States

In the United States, currently, there is no federal value-added tax (VAT) on goods or services. Instead, a sales and use tax is common in most US states. VATs have been the subject of much scholarship in the US and is one of the most contentious tax policy topics.[22][23]

In 2015, Puerto Rico passed legislation to replace its 6% sales and use tax with a 10.5% VAT beginning 1 April 2016, although the 1% municipal sales and use tax will remain and, notably, materials imported for manufacturing will be exempted.[24][25] In doing so, Puerto Rico will become the first US jurisdiction to adopt a value-added tax.[25][26] However, two states have previously enacted a form of VAT as a form of business tax in lieu of a business income tax, rather than a replacement for a sales and use tax.

The state of Michigan used a form of VAT known as the "Single Business Tax" (SBT) as its form of general business taxation. It is the only state in the United States to have used a VAT. When it was adopted in 1975, it replaced seven business taxes, including a corporate income tax. On 9 August 2006, the Michigan Legislature approved voter-initiated legislation to repeal the Single Business Tax, which was replaced by the Michigan Business Tax on 1 January 2008.[27]

The state of Hawaii has a 4% General Excise Tax (GET) that is charged on the gross income of any business entity generating income within the State of Hawaii. The State allows businesses to optionally pass on their tax burden by charging their customers a quasi sales tax rate of 4.166%.[28] The total tax burden on each item sold is more than the 4.166% charged at the register since GET was charged earlier up the sales chain (such as manufacturers and wholesalers), making the GET less transparent than a retail sales tax.[citation needed]

Discussions about a national US VAT

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2016) |

Soon after President Richard Nixon took office in 1969, it was widely reported that his administration was considering a federal VAT with the revenue to be shared with state and local governments to reduce their reliance on property taxes and to fund education spending.[citation needed] A national subtraction-method VAT, often referred to as a "flat tax", has been part of proposals by many politicians as a replacement of the corporate income tax.[2][3][4]

Trump administration

A border-adjustment tax (BAT) was proposed by the Republican Party in their 2016 policy paper "A Better Way — Our Vision for a Confident America",[29] which promoted a move to a "destination-based cash flow tax"[30]: 27 [31] (DBCFT), in part to compensate for the U.S. lacking a VAT. As of March 2017 the Trump Administration was considering including the BAT as part of its tax reform proposal.

Tax rates

European Union countries

| Country | Standard rate (current) | Reduced rate (current) | Abbreviation | Local name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20%[32] | 10% for rental for the purpose of habitation, food, garbage collection, most transportation, etc.

13% for plants, live animals and animal food, art, wine (if bought directly from the winemaker), etc.[33] |

MwSt./USt. | Mehrwertsteuer/Umsatzsteuer | |

| 21%[34] | 12% or 6% (for food or live necessary consumables) or 0% in some cases | BTW TVA MWSt |

Belasting over de toegevoegde waarde Taxe sur la Valeur Ajoutée Mehrwertsteuer | |

| 20%[32] | 9% (hotels) or 0% | ДДС | Данък добавена стойност | |

| 25%[32] | 13% (since 1 January 2014) or 5% (since 1 January 2013) | PDV | Porez na dodanu vrijednost | |

| 19%[35] | 5% (8% for taxi and bus transportation) | ΦΠΑ | Φόρος Προστιθέμενης Αξίας | |

| 21%[32][36] | 15% (food, public transport) or 10% (medicines, pharmaceuticals, books and baby foodstuffs) | DPH | Daň z přidané hodnoty | |

| 25%[32][37] | 0% | moms | Meromsætningsafgift | |

| 20%[32] | 9% | km | käibemaks | |

| 24%[32] | 14% (foodstuffs, restaurants) or 10% (medicines, cultural services and events, passenger transport, hotels, books and magazines) | ALV Moms |

Arvonlisävero (Finnish) Mervärdesskatt (Swedish) | |

| 20%[32] | 10% or 5.5% or 2.1% | TVA | Taxe sur la valeur ajoutée | |

| 19% (Heligoland 0%)[32] | 7% for foodstuffs (except luxury-), books, flowers etc., 0% for postage stamps. (Heligoland always 0%) | MwSt./USt. | Mehrwertsteuer/Umsatzsteuer | |

| 24%[32][38] (16% on Aegean islands) |

13% (6.5% for hotels, books and pharmaceutical products) (8% and 4% on Aegean islands) |

ΦΠΑ | Φόρος Προστιθέμενης Αξίας | |

| 27%[39] | 18% (milk and dairy products, cereal products, hotels, tickets to outdoor music events) or 5% (pharmaceutical products, medical equipment, books and periodicals, some meat products, district heating, heating based on renewable sources, live music performance under certain circumstances) or 0% (postal services, medical services, mother's milk, etc.)[40] | ÁFA | Általános forgalmi adó | |

| 23%[32][41] | 13.5% or 9.0% or 4.8% or 0% | CBL VAT |

Cáin Bhreisluacha (Irish) Value Added Tax (English) | |

| 22%[32] (Livigno 0%)[32] | 10% (hotels, bars, restaurants and other tourism products, certain foodstuffs, plant protection products and special works of building restoration) or 4% (e.g. grocery staples, daily or periodical press and books, works for the elimination of architectural barriers, some kinds of seeds, fertilizers) | IVA | Imposta sul Valore Aggiunto | |

| 21%[32] | 12% or 0% | PVN | Pievienotās vērtības nodoklis | |

| 21%[32] | 9% or 5% | PVM | Pridėtinės vertės mokestis | |

| 17%[42] | 14% on certain wines, 8% on public utilities, or 3% on books and press, food (including restaurant meals), children's clothing, hotel stays, and public transit[42] | TVA | Taxe sur la Valeur Ajoutée | |

| 18%[32] | 7% or 5% or 0% | VAT | Taxxa tal-Valur Miżjud | |

| 21%[32] | 6% for special categories of products and services like food, medicine and art.

0% for products and services that are already taxed in other countries or systems, for excise goods, and for fish. |

BTW | Belasting over de toegevoegde waarde/Omzetbelasting | |

| 23%[43][35] | 8% or 5% or 0% | PTU/VAT | Podatek od towarów i usług | |

| 23%[44] 22% in Madeira and 18% in Azores (Minimum 70% of mainland rate)[45] |

13% or 6% 12% or 5% in Madeira and 9% or 4% in Azores (Minimum 70% of mainland rate)[45] |

IVA | Imposto sobre o Valor Acrescentado | |

| 19%[46] | 9% (food and non-alcoholic drinks) or 5% (buyers of new homes under special conditions) | TVA | Taxa pe valoarea adăugată | |

| 20%[32] | 10% | DPH | Daň z pridanej hodnoty | |

| 22%[47] | 9.5% | DDV | Davek na dodano vrednost | |

| 21%[32] 7% in Canary Islands (not part of EU VAT area) |

10% (10% from 1 September 2012[48]) or 4%[49][50] 3% or 0% in Canary Islands |

IVA IGIC |

Impuesto sobre el Valor Añadido Impuesto General Indirecto Canario | |

| 25%[32] | 12% (e.g. food, hotels and restaurants), 6% (e.g. books, passenger transport, cultural events and activities), 0% (e.g. insurance, financial services, health care, dental care, prescription drugs, education, immovable property)[51][52] | Moms | Mervärdesskatt | |

| 20%[53] 0% on Channel Islands and Gibraltar (not part of EU VAT area) |

5% residential energy/insulation/renovations, feminine hygiene products, child safety seats and mobility aids and 0% for life necessities – basic food, water, prescription medications, medical equipment and medical supply, public transport, children's clothing, books and periodicals. Also 0% for new building construction (but standard rate for building demolition, modifications, renovation etc.)[54] | VAT | Value Added Tax |

Non-European Union countries

| Country | Standard rate (current) | Reduced rate (current) | Local name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 0% (pharmacies and medical services, books, newspapers) | TVSH = Tatimi mbi Vlerën e Shtuar | |

| 19% | |||

| 4.5% | 1% | IGI = Impost General Indirecte | |

| 15% | |||

| 21% | 10.5% or 0% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | |

| 20% | 0% | AAH = Avelacvats Arzheqi Hark ԱԱՀ = Ավելացված արժեքի հարկ | |

| 10% | 0% fresh food, medical services, medicines and medical devices, education services, childcare, water and sewerage, government taxes & permits and many government charges, precious metals, second-hand goods and many other types of goods. Rebates for exported goods and GST taxed business inputs are also available | GST = Goods and Services Tax | |

| 18% | 10.5% or 0% | ƏDV = Əlavə dəyər vergisi | |

| 7.5% | 7.5% or 0% (including but not limited to exports of goods or services, services to a foreign going vessel providing international commercial services, consumable goods for commercially scheduled foreign going vessels/aircraft, copyright, etc.) | VAT = Value Added Tax | |

| 15% | 4% for Supplier, 4.5% for ITES, 5% for electricity, 5.5% for construction firm, etc. | Musok = Mullo songzojon kor মূসক = "মূল্য সংযোজন কর" | |

| 17.5% | VAT = Value Added Tax | ||

| 20% | 10% or 0.5% | ПДВ = Падатак на дададзеную вартасьць | |

| 12.5% | |||

| 18% | |||

| 13% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | ||

| 17% | PDV = Porez na dodanu vrijednost | ||

| 12% | |||

| 20% (IPI) + 19% (ICMS) average + 3% (ISS) average | 0% | *IPI – 20% = Imposto sobre produtos industrializados (Tax over industrialized products) – Federal Tax ICMS – 17 to 25% = Imposto sobre circulação e serviços (tax over commercialization and services) – State Tax ISS – 2 to 5% = Imposto sobre serviço de qualquer natureza (tax over any service) – City tax | |

| 18% | |||

| 18% | |||

| 10% | |||

| 19.25% | |||

| 5% + 0–10% HST (GST + PVAT) | 5%/0%[a] | GST = Goods and Services Tax, TPS = Taxe sur les produits et services; HST[b] = Harmonized Sales Tax, TVH = Taxe de vente harmonisée | |

| 15% | |||

| 19% | |||

| 18% | |||

| 19% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | ||

| 17% | 13% for foods, printed matter, and households fuels; 6% or 3% | [增值税] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help) (pinyin:zēng zhí shuì) | |

| 16% (19% since 2017) | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | ||

| 13% | |||

| 16% | |||

| 15% | |||

| 18% | 12% or 0% | ITBIS = Impuesto sobre Transferencia de Bienes Industrializados y Servicios | |

| 12% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | ||

| 13% (15% on Communication Services) | VAT = Value Added Tax (الضريبة على القيمة المضافة) | ||

| 13% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado o "Impuesto a la Transferencia de Bienes Muebles y a la Prestación de Servicios" | ||

| 15% | |||

| 15% | VAT = Value Added Tax | ||

| 25% | MVG = Meirvirðisgjald | ||

| 15% | 0% | VAT = Value Added Tax | |

| 18% | |||

| 15% | VAT = Value Added Tax | ||

| 18% | 0% | DGhG = Damatebuli Ghirebulebis gadasakhadi დღგ = დამატებული ღირებულების გადასახადი | |

| 15% | VAT = Value Added Tax plus National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL; 2.5%) | ||

| 15% | |||

| 12% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | ||

| 18% | |||

| 15% | |||

| 16% | 0% | VAT = Value Added Tax | |

| 10% | |||

| 12% | |||

| 24% | 11%[d] | VSK, VASK = Virðisaukaskattur | |

| 5.5% | 5.5% | VAT = Value Added Tax | |

| 10% | 10%, 0% for primary groceries, medical services, financial services, education and also insurance | PPN = Pajak Pertambahan Nilai | |

| 9% | VAT = Value Added Tax (مالیات بر ارزش افزوده) | ||

| 20% | |||

| 17%[g] (0% in Eilat) | 0% (fruits and vegetables, tourism services for foreign citizens, intellectual property, diamonds, flights and apartments renting) | Ma'am = מס ערך מוסף, מע"מ | |

| 18% | |||

| 12.5% | |||

| 8% | shōhizei (消費税) ("consumption tax") | ||

| 5% | 0% | GST = Goods and Services Tax | |

| 16% | GST = Goods and Sales Tax | ||

| 12% | ҚCҚ = Қосылған құнға салынатын салық (Kazakh) НДС = Налог на добавленную стоимость (Russian) VAT = Value Added Tax | ||

| 16% | |||

| 18% | 8% on water supply, electricity supply, grains, milk, books etc.[61] | TVSH = Tatimi mbi Vlerën e Shtuar | |

| 20% | |||

| 10% | |||

| 10% | TVA = Taxe sur la valeur ajoutée | ||

| 14% | |||

| 8.0% | 3.8% (lodging services) or 2.5% | MWST = Mehrwertsteuer | |

| 18% | 5% or 0% | ДДВ = Данок на додадена вредност, DDV = Danok na dodadena vrednost | |

| 20% | |||

| 16.5% | |||

| 6% | 0% for fresh foods, education, healthcare and medicines | GST = Goods and Services Tax | |

| 6% | 0% | GST = Goods and Services Tax (Government Tax) | |

| 18% | |||

| 14% | |||

| 15% | VAT = Value Added Tax | ||

| 16% | 0% on books, food and medicines. | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | |

| 20% | 8%, 5% or 0% | TVA = Taxa pe Valoarea Adăugată | |

| 19.6% | 5.6% | TVA = Taxe sur la valeur ajoutée | |

| 10% | 0% | VAT = Нэмэгдсэн өртгийн албан татвар | |

| 19% | PDV = Porez na dodatu vrijednost | ||

| 20% | GST = Goods and Sales Tax (الضريبة على القيمة المضافة) | ||

| 17% | |||

| 15% | 0% | VAT = Value Added Tax | |

| 13% | 0% | VAT = Value Added Taxes | |

| 15% | GST = Goods and Services Tax | ||

| 15% | |||

| 19% | |||

| 5% | |||

| 5% | |||

| 25% | 15% (food), 8% (public transport, hotel, cinema) and 0% for electric cars (until 2018)[65] | MVA = Merverdiavgift (bokmål) or meirverdiavgift (nynorsk) (informally moms) | |

| 17% | 1% or 0% | GST = General Sales Tax | |

| 16% | VAT = Value Added Tax | ||

| 7% | 0% | ITBMS = Impuesto de Transferencia de Bienes Muebles y Servicios | |

| 10% | |||

| 10% | 5% | IVA= Impuesto al Valor Agregado | |

| 18% | IGV – 16% = Impuesto General a la Ventas IPM – 2% Impuesto de Promocion Municipal | ||

| 12%[j] | 6% on petroleum products, and electricity and water services 0% for senior citizens (all who are aged 60 and above) on medicines, professional fees for physicians, medical and dental services, transportation fares, admission fees charged by theaters and amusement centers, and funeral and burial services after the death of the senior citizen |

RVAT = Reformed Value Added Tax, locally known as Karagdagang Buwis / Dungag nga Buhis | |

| 16% | |||

| 18% | 10% or 0% | НДС = Налог на добавленную стоимость, NDS = Nalog na dobavlennuyu stoimost’ | |

| 18% | 0% | VAT = Value Added Tax | |

| 17% | VAT = Value Added Tax | ||

| 15% | |||

| 15% | |||

| 18% | |||

| 20%[67] | 10%[68] or 0% | ПДВ = Порез на додату вредност, PDV = Porez na dodatu vrednost | |

| 15% | |||

| 15% | |||

| 7% | GST = Goods and Services Tax | ||

| 14% | 0% on basic foodstuffs such as bread, additionally on goods donated not for gain; goods or services used for educational purposes, such as school computers; membership contributions to an employee organization (such as labour union dues); and rent paid on a house by a renter to a landlord.[69] | VAT = Valued Added Tax; BTW = Belasting op toegevoegde waarde | |

| 10% | VAT = bugase (Korean: 부가세) | ||

| 12% | 0% | VAT = Valued Added Tax has been in effect in Sri Lanka since 2001. On the 2001 budget, the rates have been revised to 12% and 0% from the previous 20%, 12% and 0% | |

| 17% | |||

| 8%[49] | 3.8% (hotel sector) and 2.5% (essential foodstuff, books, newspapers, medical supplies)[49] | MWST = Mehrwertsteuer, TVA = Taxe sur la valeur ajoutée, IVA = Imposta sul valore aggiunto, TPV = Taglia sin la Plivalur | |

| 5% | [增值稅] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help) (pinyin:zēng zhí shuì) | ||

| 20% | |||

| 18% | |||

| 10% | 7% | VAT = Value Added Tax, ภาษีมูลค่าเพิ่ม | |

| 18% | |||

| 15% | |||

| 12.5% | 0% | ||

| 18% | TVA = Taxe sur la Valeur Ajoutée آداء على القيمة المضافة | ||

| 18% | 8% or 1% | KDV = Katma değer vergisi | |

| 15% | |||

| 18% | |||

| 20% | 7% or 0% | ПДВ = Податок на додану вартість, PDV = Podatok na dodanu vartist’. | |

| 18% | 11% or 0% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | |

| 20% | НДС = Налог на добавленную стоимость | ||

| 13% | |||

| 10% | 5% or 0% | GTGT = Giá Trị Gia Tăng | |

| 12% | 11% | IVA = Impuesto al Valor Agregado | |

| 16% | |||

| 15% |

- ^ No real "reduced rate", but rebates generally available for new housing effectively reduce the tax to 4.5%.

- ^ HST is a combined federal/provincial VAT collected in some provinces. In the rest of Canada, the GST is a 5% federal VAT and if there is a Provincial Sales Tax (PST) it is a separate non-VAT tax.

- ^ These taxes do not apply in Hong Kong and Macau, which are financially independent as special administrative regions.

- ^ The reduced rate was 14% until 1 March 2007, when it was lowered to 7%, and later changed to 11%. The reduced rate applies to heating costs, printed matter, restaurant bills, hotel stays, and most food.

- ^ VAT is not implemented in 2 of India's 28 states.

- ^ Except Eilat, where VAT is not raised.[60]

- ^ The VAT in Israel is in a state of flux. It was reduced from 18% to 17% in March 2004, to 16.5% in September 2005, then to 15.5% in July 2006. It was then raised back to 16.5% in July 2009, and lowered to the rate of 16% in January 2010. It was then raised again to 17% on 1 September 2012, and once again on 2 June 2013, to 18%. It was reduced from 18% to 17% in October 2015.

- ^ The introduction of a goods and sales tax of 3% on 6 May 2008 was to replace revenue from Company Income Tax following a reduction in rates.

- ^ In the 2014 Budget, the government announced that GST would be introduced in April 2015. Piped water, power supply (the first 200 units per month for domestic consumers), transportation services, education, and health services are tax-exempt. However, many details have not yet been confirmed.[63]

- ^ The President of the Philippines has the power to raise the tax to 12% after 1 January 2006. The tax was raised to 12% on 1 February.[66]

VAT free countries and territories

As of March 2016, the countries and territories listed remained VAT free.[citation needed]

| Country[70] | Notes |

|---|---|

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| Gulf Co-operation Council | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| — | |

| — | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| British Crown Dependency | |

| Special administrative region of China | |

| — | |

| — | |

| Gulf Co-operation Council | |

| — | |

| — | |

| Special administrative region of China | |

| — | |

| — | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| — | |

| — | |

| Gulf Co-operation Council | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| Gulf Co-operation Council | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| — | |

| Gulf Co-operation Council | |

| — | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| — | |

| — | |

| — | |

| — | |

| British Overseas Territory | |

| — | |

| Gulf Co-operation Council (5% VAT planned January 1, 2018) | |

| Sales taxes are collected by most states and some cities, counties, and Native American reservations. The federal government collects excise tax on some goods, but does not collect a nationwide sales tax. | |

| — | |

| — |

Criticisms

The "value-added tax" has been criticized as the burden of it falls on personal end-consumers of products. Some critics consider it to be a regressive tax, meaning that the poor pay more, as a percentage of their income, than the rich. Defenders argue that relating taxation levels to income is an arbitrary standard, and that the value-added tax is in fact a proportional tax in that people with higher income pay more in that they consume more. The effective progressiveness or regressiveness of a VAT system can also be affected when different classes of goods are taxed at different rates. To maintain the progressive nature of total taxes on individuals, countries implementing VAT have reduced income tax on lower income-earners as well as instituted direct transfer payments to lower-income groups, resulting in lower tax burdens on the poor.[71]

Revenues from a value-added tax are frequently lower than expected because they are difficult and costly to administer and collect. In many countries, however, where collection of personal income taxes and corporate profit taxes has been historically weak, VAT collection has been more successful than other types of taxes. VAT has become more important in many jurisdictions as tariff levels have fallen worldwide due to trade liberalization, as VAT has essentially replaced lost tariff revenues. Whether the costs and distortions of value-added taxes are lower than the economic inefficiencies and enforcement issues (e.g. smuggling) from high import tariffs is debated, but theory suggests value-added taxes are far more efficient.

Certain industries (small-scale services, for example) tend to have more VAT avoidance, particularly where cash transactions predominate, and VAT may be criticized for encouraging this. From the perspective of government, however, VAT may be preferable because it captures at least some of the value added. For example, a building contractor may offer to provide services for cash (i.e. without a receipt, and without VAT) to a homeowner, who usually cannot claim input VAT back. The homeowner will thus bear lower costs and the building contractor may be able to avoid other taxes (profit or payroll taxes).

Another avenue of criticism of implementing a VAT is that the increased tax passed to the consumer will increase the ultimate price paid by the consumer. However, a study in Canada reveals that in fact when replacing a traditional sales tax with a VAT consumer prices including taxes actually fell, by –0.3%±0.49%.[72]

Trade criticism

Because exports are generally zero-rated (and VAT refunded or offset against other taxes), this is often where VAT fraud occurs. In Europe, the main source of problems is called carousel fraud. [citation needed] This kind of fraud originated in the 1970s in the Benelux countries. Today, VAT fraud is a major problem in the UK.[74] There are also similar fraud possibilities inside a country. To avoid this, in some countries like Sweden, the major owner of a limited company is personally responsible for taxes.[73]

Under a sales tax system, only businesses selling to the end-user are required to collect tax and bear the accounting cost of collecting the tax. Under VAT, manufacturers and wholesale companies also incur accounting expenses to handle the additional paperwork required for collecting VAT, increasing overhead costs. Manufacturers and wholesalers have a choice of retaining less profits overall, or passing on the additional cost to their customers in the form of increased prices.

Many politicians and economists in the United States consider VAT taxation on US goods and VAT rebates for goods from other countries to be unfair practice. E.g. the American Manufacturing Trade Action Coalition claims that any rebates or special taxes on imported goods should not be allowed by the rules of the World Trade Organisation. AMTAC claims that so-called "border tax disadvantage" is the greatest contributing factor to the $5.8 trillion US current account deficit for the decade of the 2000s, and estimated this disadvantage to US producers and service providers to be $518 billion in 2008 alone. Some US politicians, such as congressman Bill Pascrell, are advocating either changing WTO rules relating to VAT or rebating VAT charged on US exporters by passing the Border Tax Equity Act.[75] A business tax rebate for exports is also proposed in the 2016 GOP policy paper for tax reform.[76][77] The assertion that this "border adjustment" would be compatible with the rules of the WTO is controversial; it was alleged that the proposed tax would favour domestically produced goods as they would be taxed less than imports, to a degree varying across sectors. For example, the wage component of the cost of domestically produced goods would not be taxed.[78]

See also

- Border-adjustment tax (United States)

- Excise

- Flat tax

- Gross receipts tax

- Income tax

- Indirect tax

- Land value tax

- Missing Trader Fraud (Carousel VAT Fraud)

- Progressive tax

- Single tax

- Turnover tax

- X tax

General:

Notes

- ^ a b Consumption Tax Trends 2014: VAT/GST and excise rates, trends and policy issues. Secretary-General of the OECD. 2014. doi:10.1787/ctt-2014-en. ISBN 978-92-64-22394-3. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ a b Bickley, James M. (3 January 2008). Value-Added Tax: A New U.S. Revenue Source? (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 1, 3. RL33619. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cole, Alan (29 October 2015). "Ted Cruz's "Business Flat Tax:" A Primer". Tax Policy Blog. Tax Foundation. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ a b Beram, Philip. An Introduction to the Value Added Tax (VAT) (PDF) (Report). United States Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Helgason, Agnar Freyr. "Unleashing the 'money machine': the domestic political foundations of VAT adoption". Socio-Economic Review. doi:10.1093/ser/mwx004.

- ^ "Les recettes fiscales". Le budget et les comptes de l’État (in French). Minister of the Economy, Industry and Employment (France). 30 October 2009.

la TVA représente 125,4 milliards d'euros, soit 49,7 % des recettes fiscales nettes de l'État.

- ^ Bodin, Jean-Paul; Ebril, Liam P.; Keen, Michael; Summers, Victoria P. (5 November 2001). The Modern VAT. International Monetary Fund. ISBN 9781589060265. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Understanding cash and accrual basis accounting – Products – Office.com. Office.microsoft.com. Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Cima F2 Exam Questions". Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ http://www.taxanalysts.com/www/freefiles.nsf/Files/SLEMROD-14.pdf/$file/SLEMROD-14.pdf

- ^ China's VAT System – Beijing Review. Bjreview.com.cn (3 August 2009). Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/resources/documents/taxation/vat/how_vat_works/rates/vat_rates_en.pdf

- ^ Thacker, Sunil (2008–2009). "Taxation in the Gulf: Introduction of a Value Added Tax". Michigan State Journal of International Law. 17 (3): 721. SSRN 1435988.

- ^ http://gulfnews.com/business/economy/uae-outlines-vat-threshold-for-firms-in-phase-1-1.1847025

- ^ http://www.pwc.com/m1/en/services/tax/me-tax-legal-news/2016/uae-to-implement-vat-on-1-january-2018.html

- ^ Vuoristo, Pekka. "Hallitus sopuun ruan veroalesta", Helsingin Sanomat, 2005-08-266. Retrieved on 26 August 2009.

- ^ "The Value Added Tax Act with subsequent amendments" (PDF). Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs. 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Main features of the Government's tax programme for 2011". Ministry of Finance. 5 October 2010.

- ^ "Merverdiavgiftsloven §§ 6–21 to 6–33" (in Norwegian). www.lovdata.no. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Merverdiavgiftsloven §§ 6-1 to 6–20" (in Norwegian). www.lovdata.no. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Thor, Anatoliy. "Company formation in Ukraine".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Trinova Corp. v. Michigan Dept. of Treasury, 498 U.S. 358, 362 (United States Supreme Court 1991) ("Although in Europe and Latin America VAT's are common,...in the United States they are much studied but little used.").

- ^ Gulino, Denny (18 September 2015). "Puerto Rico May Finally Get Attention of Republican Lawmakers". MNI. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

The concept of a value added tax in any form as part of the U.S. tax regime has consistently raised the hackles of Republican policy makers and even some Democrats because of fears it could add to the tax burden rather than just redistribute it to consumption from earnings. For decades one of the most hotly debated tax policy topics, a VAT imposes a sales tax at every stage where value is added.

- ^ "Puerto Rico adopts VAT tax system and broadens sales and use tax" (PDF). PricewaterhouseCooper. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b Harpaz, Joe (17 September 2015). "Puerto Rico Brings First-Ever Value-Added Tax To The U.S." Forbes. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Examining Puerto Rico Tax Regime Changes: Addition of Value Added Tax and Amendments to Sales and Use, Income Taxes". Bloomberg BNA. 11 January 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

Puerto Rico's adoption of a VAT represents a major shift in tax policy and renders the Commonwealth as the first U.S. jurisdiction to adopt this tax regime.

- ^ Outline of the Michigan Tax System, Citizens Research Council of Michigan, January 2011 Archived 5 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lingle, Linda and Kawafuchi, Kurt (June 2002). An introduction to the general excise tax. State of Hawaii, Department of taxation

- ^ Ryan Ellis (5 January 2017), Tax Reform, Border Adjustability, and Territoriality: When tax and fiscal policy meets political reality, Forbes, retrieved 18 February 2017

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "A Better Way— Our Vision for a Confident America" (PDF). Republican Party (United States). 24 June 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ William G. Gale (7 February 2017). "A quick guide to the 'border adjustments' tax". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "2014 EU VAT rates". VAT Live. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ "BMF - Umsatzsteuer Info zum Steuerreformgesetz 2015/2016". www.bmf.gv.at. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "2016 AGN VAT Brochure - European Comparison" (PDF). Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ a b "2016 AGN VAT Brochure - European Comparison" (PDF). Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Companies welcome VAT resolved. Prague Monitor (27 December 2012). Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ Tax in Denmark: An introduction – for new citizens. SKAT.dk (November 2005)

- ^ Οι νέοι συντελεστές ΦΠΑ από 1 Ιουλίου. Madata.GR (9 October 2008). Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ Index – Gazdaság – Uniós csúcsra emeljük az áfát. Index.hu (16 September 2011). Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ Áfa kulcsok és a tevékenység közérdekű vagy egyéb sajátos jellegére tekintettel adómentes tevékenységek köre 2015. január 1-jétől (PDF; in Hungarian)

- ^ VAT Rates. Revenue.ie. Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ a b http://www.aed.public.lu/tva/loi/Loi-TVA-2015.pdf

- ^ Prezydent podpisał ustawę okołobudżetową – VAT wzrośnie do 23 proc. Wyborcza.biz (14 December 2010). Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ Taxas de portagens aumentam 2,2 por cento em 2011 – PÚBLICO. Economia.publico.pt (31 December 2010). Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ a b "Madeira – VAT rate hike". Tmf-vat.com. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Andra, Timu (3 September 2015). "Romania Passes Scaled-Down Tax Cuts After Warnings Over Budget". Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Pravilnik o spremembah in dopolnitvah Pravilnika o izvajanju Zakona o davku na dodano vrednost". Ministry of Finance. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ "Spain raises VAT from 18% to 21% 1 September 2012". VAT Live. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ a b c "VAT Live". VAT Live. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ LondonStockExschange.com[dead link]

- ^ "Swedish VAT compliance and rates". VAT Live. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ "Momsen - hur fungerar den? | Skatteverket". Skatteverket.se. 1 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ "Budget: How the rise in VAT will work". BBC News. BBC. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "VAT rates on different goods and services - Detailed guidance - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Andorra crea un IVA con un tipo general del 4,5% y uno reducido del 1%". La Vanguardia. 4 July 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ "The Government of The Bahamas - VAT Bahamas". VAT Bahamas. 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "Bahamas Planning to Introduce 7.5 Percent Value Added Tax in 2015". Caribbean Journal. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "Gambia Revenue Authority - VAT". Gambia Revenue Authority. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ "Ram & McRae's Investors Information Package". Ramandmcrae.com. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ VAT in Eilat, ECCB

- ^ "PËR TATIMIN MBI VLERËN E SHTuAR" (PDF).

- ^ "Value added tax". Portal of the Principality of Liechtenstein. Government Spokesperson's Office. Archived from the original on 18 April 2005. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ [1], International Business Times

- ^ "Monaco capital gains tax rates, and property income tax". Globalpropertyguide.com. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Norway confirms electric car incentives until 2018". Thegreencarwebsite.co.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Bureau of Internal Revenue Website. Bir.gov.ph. Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ Blic Online | Opšta stopa PDV od 1. oktobra biće 20 odsto. Blic.rs. Retrieved on 14 June 2013.

- ^ http://www.b92.net/biz/vesti/srbija.php?yyyy=2014&mm=01&dd=01&nav_id=795544

- ^ "Value-Added Tax". www.sars.gov.za. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "TAX RATES". taxrates web site. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ Chia-Tern Huey Min (October 2004) GST in Singapore: Policy Rationale, Implementation Strategy & Technical Design, Singapore Ministry of Finance.

- ^ Smart, Michael; Bird, Richard M. (2009). "The Economic Incidence of Replacing a Retail Sales Tax with a Value-Added Tax: Evidence from Canadian Experience" (PDF). Canadian Public Policy. 35 (1): 85–97. doi:10.1353/cpp.0.0007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b http://economyincrisis.org/content/now-is-the-time-to-reform-the-income-tax-with-a-vat

- ^ O'Grady, Sean (26 July 2007) Carousel fraud 'has cost UK up to £16bn', The Independent.

- ^ "Border Adjusted Taxation / Value Added Tax (VAT)". Amtacdc.org. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Thiessen, Marc A. (17 January 2017). "Yes, Trump can make Mexico pay for the border wall. Here's how". Washington Post. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "A Better Way— Our Vision for a Confident America" (PDF). Republican Party (United States). 24 June 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ Freund, Caroline (18 January 2017). "Trump Is Right: 'Border Adjustment' Tax Is Complicated". BloombergView. Bloomberg LP. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

- "Lög nr. 50/1988 um virðisaukaskatt" (in Icelandic). 1988. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- Ahmed, Ehtisham and Nicholas Stern. 1991. The Theory and Practice of Tax Reform in Developing Countries (Cambridge University Press).

- Bird, Richard M. and P.-P. Gendron .1998. "Dual VATs and Cross-border Trade: Two Problems, One Solution?" International Tax and Public Finance, 5: 429–42.

- Bird, Richard M. and P.-P. Gendron .2000. "CVAT, VIVAT and Dual VAT; Vertical ‘Sharing’ and Interstate Trade," International Tax and Public Finance, 7: 753–61.

- Smart, M., & Bird, R. M. (2009). The impact on investment of replacing a retail sales tax with a value-added tax: Evidence from Canadian experience. National Tax Journal, 591-609.

- Keen, Michael and S. Smith .2000. "Viva VIVAT!" International Tax and Public Finance, 7: 741–51.

- Keen, Michael and S. Smith .1996. "The Future of Value-added Tax in the European Union," Economic Policy, 23: 375–411.

- McLure, Charles E. (1993) "The Brazilian Tax Assignment Problem: Ends, Means, and Constraints," in A Reforma Fiscal no Brasil (São Paulo: Fundaçäo Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas).

- McLure, Charles E. 2000. "Implementing Subnational VATs on Internal Trade: The Compensating VAT (CVAT)," International Tax and Public Finance, 7: 723–40.

- Muller, Nichole. 2007. Indisches Recht mit Schwerpunkt auf gewerblichem Rechtsschutz im Rahmen eines Projektgeschäfts in Indien, IBL Review, VOL. 12, Institute of International Business and law, Germany. Law-and-business.de

- Muller, Nichole. 2007. Indian law with emphasis on commercial legal insurance within the scope of a project business in India. IBL Review, VOL. 12, Institute of International Business and law, Germany.

- MOMS, Politikens Nudansk Leksikon 2002, ISBN 87-604-1578-9.

- OECD. 2008. Consumption Tax Trends 2008: VAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trends and Administration Issues. Paris: OECD.

- Serra, J. and J. Afonso. 1999. "Fiscal Federalism Brazilian Style: Some Reflections," Paper presented to Forum of Federations, Mont Tremblant, Canada, October 1999.

- Sharma, Chanchal Kumar 2005. Implementing VAT in India: Implications for Federal Polity. Indian Journal of Political Science, LXVI (4): 915–934. ISSN 0019-5510 SSRN.com

- Shome, Parthasarathi and Paul Bernd Spahn (1996) "Brazil: Fiscal Federalism and Value Added Tax Reform," Working Paper No. 11, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, New Delhi

- Silvani, Carlos and Paulo dos Santos (1996) "Administrative Aspects of Brazil's Consumption Tax Reform," International VAT Monitor, 7: 123–32.

- Tait, Alan A. (1988) Value Added Tax: International Practice and Problems (Washington: International Monetary Fund).