Voynich manuscript

| Voynich manuscript | |

|---|---|

| Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University | |

| |

| Type | Codex |

| Date | Early 15th century[1][2] |

| Place of origin | Possibly Northern Italy[1][2] |

| Material | Vellum |

| Size | 23.5 by 16.2 by 5 cm (9.3 by 6.4 by 2.0 in) |

The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated codex hand-written in an unknown writing system. The vellum on which it is written has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century (1404–1438), and it may have been composed in Northern Italy during the Italian Renaissance.[1][2] The manuscript is named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish book dealer who purchased it in 1912.[3]

Some of the pages are missing, with around 240 still remaining. The text is written from left to right, and most of the pages have illustrations or diagrams.

The Voynich manuscript has been studied by many professional and amateur cryptographers, including American and British codebreakers from both World War I and World War II.[4] No one has yet succeeded in deciphering the text, and it has become a famous case in the history of cryptography. The mystery of the meaning and origin of the manuscript has excited the popular imagination, making the manuscript the subject of novels and speculation. None of the many hypotheses proposed over the last hundred years has yet been independently verified.[5]

The Voynich manuscript was donated by Hans P. Kraus[6] to Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in 1969, where it is catalogued under call number MS 408.[7][8]

Description

Codicology

The manuscript measures 23.5 by 16.2 by 5 centimetres (9.3 by 6.4 by 2.0 in), with hundreds of vellum pages collected into eighteen quires. The total number of pages is around 240, but the exact number depends on how the manuscript's unusual foldouts are counted.[8] The quires have been numbered from 1 to 20 in various locations, with numerals consistent with the 1400s, and the top righthand corner of each recto (righthand) page has been numbered from 1 to 116, with numerals of a later date. From the various numbering gaps in the quires and pages, it seems likely that in the past the manuscript had at least 272 pages in 20 quires, some of which were already missing when Wilfrid Voynich acquired the manuscript in 1912. There is strong evidence that many of the book's bifolios were reordered at various points in its history, and that the original page order may well have been quite different from what it is today.[9][10]

The binding and covers are not original to the book, but date to during its possession by the Collegio Romano.[8]

Every page in the manuscript contains text, mostly in an unknown script, but some have extraneous writing in Latin script. Many pages contain substantial drawings or charts which are colored with paint. Based on modern analysis, it has been determined that a quill pen and iron gall ink were used for the text and figure outlines; the colored paint was applied (somewhat crudely) to the figures, possibly at a later date.[10]

Text

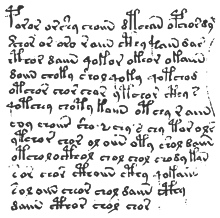

The bulk of the text in the manuscript of 240 pages is written in an unknown script, running left to right. Most of the characters are composed of one or two simple pen strokes. While there is some dispute as to whether certain characters are distinct or not, a script of 20–25 characters would account for virtually all of the text; the exceptions are a few dozen rarer characters that occur only once or twice each. There is no obvious punctuation.[11]

Much of the text is written in a single column in the body of a page, with a slightly ragged right margin and paragraph divisions, and sometimes with stars in the left margin.[8] Other text occurs in charts or as labels associated with illustrations. There are no indications of any errors or corrections made at any place in the document. The ductus flows smoothly, giving the impression that the symbols were not enciphered, as there is no delay between characters as would normally be expected in written encoded text.

The text consists of over 170,000 characters,[12] with spaces dividing the text into about 35,000 groups of varying length, usually referred to as "words". The structure of these words seems to follow phonological or orthographic laws of some sort, e.g., certain characters must appear in each word (like English vowels), some characters never follow others, some may be doubled or tripled but others may not, etc.[citation needed] The distribution of letters within words is also rather peculiar: some characters occur only at the beginning of a word, some only at the end, and some always in the middle section.[citation needed] Many researchers have commented upon the highly regular structure of the words.[13]

Some words occur only in certain sections, or in only a few pages; others occur throughout the manuscript. There are very few repetitions among the thousand or so labels attached to the illustrations. There are practically no words with fewer than two letters or more than ten.[12] There are instances where the same common word appears up to three times in a row.[12] Words that differ by only one letter also repeat with unusual frequency, causing single-substitution alphabet decipherings to yield babble-like text. In 1962, Elizebeth Friedman described such attempts as "doomed to utter frustration".[14]

Various transcription alphabets have been created to equate the Voynich characters with Latin characters in order to help with cryptanalysis, such as the European Voynich Alphabet. The first major one was created by cryptographer William F. Friedman in the 1940s, where each line of the manuscript was transcribed to an IBM punch card to make it machine readable.[15]

Extraneous writing

Only a few words in the manuscript are considered not to be written in the unknown script:[16]

- f1r: A sequence of Latin letters in the right margin parallel with characters from the unknown script. There is also the now unreadable signature of "Jacobj à Tepenece" in the bottom margin.

- f17r: A line of writing in the Latin script in the top margin.

- f70v–f73v: The astrological series of diagrams in the astronomical section has the names of ten of the months (from March to December) written in Latin script, with spelling suggestive of the medieval languages of France, northwest Italy or the Iberian Peninsula.[17]

- f66r: A small number of words in the bottom left corner near a drawing of a naked man. They have been read as "der musz del", a High German[16] word for a widow's share.

- f116v: Four lines of writing written in rather distorted Latin script, except for two words in the unknown script. The words in Latin script appear to be distorted with characteristics of the unknown language. The lettering resembles European alphabets of the late 14th and 15th centuries, but the words do not seem to make sense in any language.[18]

It is not known whether these bits of Latin script were part of the original text or were added later.

Illustrations

Because the text cannot be read, the illustrations are conventionally used to divide most of the manuscript into six different sections. Each section is typified by illustrations with different styles and supposed subject matter,[12] except for the last section, in which the only drawings are small stars in the margin. Following are the sections and their conventional names:

- Herbal: Each page displays one or two plants and a few paragraphs of text—a format typical of European herbals of the time. Some parts of these drawings are larger and cleaner copies of sketches seen in the "pharmaceutical" section. None of the plants depicted are unambiguously identifiable.[8]

- Astronomical: Contains circular diagrams, some of them with suns, moons, and stars, suggestive of astronomy or astrology. One series of 12 diagrams depicts conventional symbols for the zodiacal constellations (two fish for Pisces, a bull for Taurus, a hunter with crossbow for Sagittarius, etc.). Each of these has 30 female figures arranged in two or more concentric bands. Most of the females are at least partly naked, and each holds what appears to be a labeled star or is shown with the star attached by what could be a tether or cord of some kind to either arm. The last two pages of this section (Aquarius and Capricornus, roughly January and February) were lost, while Aries and Taurus are split into four paired diagrams with 15 women and 15 stars each. Some of these diagrams are on fold-out pages.[8]

- Biological: A dense continuous text interspersed with figures, mostly showing small naked women, some wearing crowns, bathing in pools or tubs connected by an elaborate network of pipes.

- Cosmological: More circular diagrams, but of an obscure nature. This section also has foldouts; one of them spans six pages and contains a map or diagram, with nine "islands" or "rosettes" connected by "causeways" and containing castles, as well as what might be a volcano.[8]

- Pharmaceutical: Many labeled drawings of isolated plant parts (roots, leaves, etc.); objects resembling apothecary jars, ranging in style from the mundane to the fantastical; and a few text paragraphs.[8]

- Recipes: Full pages of text broken into many short paragraphs each marked with a star in the left margin.[8]

Purpose

The overall impression given by the surviving leaves of the manuscript is that it was meant to serve as a pharmacopoeia or to address topics in medieval or early modern medicine. However, the puzzling details of illustrations have fueled many theories about the book's origins, the contents of its text, and the purpose for which it was intended.[12]

The first section of the book is almost certainly herbal, but attempts to identify the plants, either with actual specimens or with the stylized drawings of contemporary herbals, have largely failed.[19] Only a few of the plant drawings (such as a wild pansy and the maidenhair fern) can be identified with reasonable certainty. Those herbal pictures that match pharmacological sketches appear to be clean copies of these, except that missing parts were completed with improbable-looking details. In fact, many of the plant drawings in the herbal section seem to be composite: the roots of one species have been fastened to the leaves of another, with flowers from a third.[19]

Hugh O'Neill believed that one illustration depicted a New World sunflower, which would help date the manuscript and open up intriguing possibilities for its origin; unfortunately the identification is only speculative.[12]

The basins and tubes in the "biological" section are sometimes interpreted as implying a connection to alchemy, yet bear little obvious resemblance to the alchemical equipment of the period.[citation needed]

Astrological considerations frequently played a prominent role in herb gathering, bloodletting and other medical procedures common during the likeliest dates of the manuscript. However, apart from the obvious Zodiac symbols, and one diagram possibly showing the classical planets, interpretation remains speculative.[12]

History

Much of the early history of the book is unknown,[20] though the text and illustrations are all characteristically European. In 2009, University of Arizona researchers performed radiocarbon dating on the manuscript's vellum. The result of that test put the date the manuscript was made between 1404 and 1438.[2][21][22] In addition, the McCrone Research Institute in Chicago found that the paints in the manuscript were of materials to be expected from that period of European history. It has also been suggested that the McCrone Research Institute found that much of the ink was added not long after the creation of the parchment, but the official report contains no statement to this effect.[10]

The earliest historical information about the manuscript comes from a letter found inside the cover—written in 1666 to accompany the manuscript when it was sent by Johannes Marcus to Athanasius Kircher—which claims that the book once belonged to Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612), who paid 600 gold ducats (~2.07 kg gold) for it. The book was then given or lent to Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenecz (died 1622), the head of Rudolf's botanical gardens in Prague.

The next confirmed owner is Georg Baresch, an obscure alchemist also in Prague. Baresch was apparently just as puzzled as modern scientists about this "Sphynx" that had been "taking up space uselessly in his library" for many years.[23] On learning that Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit scholar from the Collegio Romano, had published a Coptic (Egyptian) dictionary and "deciphered" the Egyptian hieroglyphs, Baresch sent a sample copy of the script to Kircher in Rome (twice), asking for clues. His 1639 letter to Kircher is the earliest confirmed mention of the manuscript that has been found so far.[24]

It is not known whether Kircher answered the request, but apparently, he was interested enough to try to acquire the book, which Baresch refused to yield. Upon Baresch's death, the manuscript passed to his friend Jan Marek Marci (1595–1667) (Johannes Marcus Marci), then rector of Charles University in Prague, who a few years later sent the book to Kircher, his longtime friend and correspondent.[24] Marci's 1666 cover letter (written in Latin) was still with the manuscript when Voynich purchased it:[11]

Reverend and Distinguished Sir, Father in Christ:

This book, bequeathed to me by an intimate friend, I destined for you, my very dear Athanasius, as soon as it came into my possession, for I was convinced that it could be read by no one except yourself.

The former owner of this book asked your opinion by letter, copying and sending you a portion of the book from which he believed you would be able to read the remainder, but he at that time refused to send the book itself. To its deciphering he devoted unflagging toil, as is apparent from attempts of his which I send you herewith, and he relinquished hope only with his life. But his toil was in vain, for such Sphinxes as these obey no one but their master, Kircher. Accept now this token, such as it is and long overdue though it be, of my affection for you, and burst through its bars, if there are any, with your wonted success.

Dr. Raphael, a tutor in the Bohemian language to Ferdinand III, then King of Bohemia, told me the said book belonged to the Emperor Rudolph and that he presented to the bearer who brought him the book 600 ducats. He believed the author was Roger Bacon, the Englishman. On this point I suspend judgement; it is your place to define for us what view we should take thereon, to whose favor and kindness I unreservedly commit myself and remain

- At the command of your Reverence,

- Joannes Marcus Marci of Cronland

- Prague, 19th August, 1666[11]

There are no records of the book for the next 200 years, but in all likelihood it was stored with the rest of Kircher's correspondence in the library of the Collegio Romano (now the Pontifical Gregorian University).[24] It probably remained there until the troops of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy captured the city in 1870 and annexed the Papal States. The new Italian government decided to confiscate many properties of the Church, including the library of the Collegio.[24] According to investigations by Xavier Ceccaldi and others, just before this happened, many books of the University's library were hastily transferred to the personal libraries of its faculty, which were exempt from confiscation.[24] Kircher's correspondence was among those books—and so apparently was the Voynich manuscript, as it still bears the ex libris of Petrus Beckx, head of the Jesuit order and the University's Rector at the time.[8][24]

Beckx's "private" library was moved to the Villa Mondragone, Frascati, a large country palace near Rome that had been bought by the Society of Jesus in 1866 and housed the headquarters of the Jesuits' Ghislieri College.[24]

Around 1912, the Collegio Romano was short of money and decided to sell some of its holdings discreetly. Wilfrid Voynich acquired 30 manuscripts, among them the manuscript that now bears his name.[24] He spent the next seven years attempting to interest scholars in deciphering the script while he worked to determine the origins of the manuscript.[11]

In 1930, after Wilfrid's death, the manuscript was inherited by his widow, Ethel Voynich (known as the author of the novel The Gadfly and daughter of mathematician George Boole). She died in 1960 and left the manuscript to her close friend, Miss Anne Nill. In 1961, Nill sold the book to another antique book dealer, Hans P. Kraus. Unable to find a buyer, Kraus donated the manuscript to Yale University in 1969, where it was catalogued as "MS 408".[16] In discussions, it is sometimes also referred to as "Beinecke MS 408".[8]

Authorship hypotheses

Many people have been proposed as possible authors of the Voynich manuscript.

Marci's 1666 cover letter to Kircher says that, according to his friend, the late Raphael Mnishovsky, the book had once been bought by Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia (1552–1612), for 600 ducats (66.42 troy ounce actual gold weight, or 2.07 kg). (Mnishovsky had died 22 years earlier, in 1644, and the deal must have occurred before Rudolf's abdication in 1611—at least 55 years before Marci's letter.) According to the letter, Mnishovsky (but not necessarily Rudolf) speculated that the author was the Franciscan friar and polymath Roger Bacon (1214–94).[25] Even though Marci said that he was "suspending his judgment" about this claim, it was taken quite seriously by Wilfrid Voynich, who did his best to confirm it.[24]

The assumption that Roger Bacon was the author led Voynich to conclude that the person who sold the manuscript to Rudolf could only have been John Dee (1527–1608), a mathematician and astrologer at the court of Queen Elizabeth I of England, known to have owned a large collection of Bacon's manuscripts. Dee and his scrier (mediumic assistant) Edward Kelley lived in Bohemia for several years, where they had hoped to sell their services to the emperor. However, this seems quite unlikely, because Dee's meticulously kept diaries do not mention that sale.[24] If the Voynich manuscript author is not Bacon, a supposed connection to Dee is much weakened. Until the carbon dating of the manuscript to the 15th century, it was thought possible that Dee or Kelley may have written it and spread the rumor that it was originally a work of Bacon's in the hopes of later selling it.[citation needed]

Fabrication by Voynich

Some suspected Voynich of having fabricated the manuscript himself.[26] As an antique book dealer, he probably had the necessary knowledge and means, and a "lost book" by Roger Bacon would have been worth a fortune. Furthermore, Baresch's letter (and Marci's as well) only establish the existence of a manuscript, not that the Voynich manuscript is the same one spoken of there. In other words, these letters could possibly have been the motivation for Voynich to fabricate the manuscript (assuming he was aware of them), rather than as proofs authenticating it. However, many consider the expert internal dating of the manuscript and the recent[when?] discovery of Baresch's letter to Kircher as having eliminated this possibility.[24][26]

Other theories

Voynich was able, sometime before 1921, to read a name faintly written at the foot of the manuscript's first page: "Jacobj à Tepenece". This is taken to be a reference to Jakub Hořčický of Tepenec (1575–1622), also known by his Latin name Jacobus Sinapius. Rudolph II had ennobled him in 1607; appointed him his Imperial Distiller; and had made him both curator of his botanical gardens as well as one of his personal physicians. Voynich, and many other people after him, concluded from this that Jacobus owned the Voynich manuscript prior to Baresch, and drew a link to Rudolf's court from that, in confirmation of Mnishovsky's story.

Jacobus's name is still clearly visible under UV light: however, it does not match the copy of his signature in a document located by Jan Hurych in 2003.[27] As a result, it has been suggested that the signature was added later, possibly even fraudulently by Voynich himself. Yet because the writing on page f1r might well have been an ownership mark added by a librarian at the time, the difference between the two signatures does not necessarily disprove Horczicky's ownership.

It has been noted that Baresch's letter bears some resemblance to a hoax that orientalist Andreas Mueller once played on Kircher. Mueller sent some unintelligible text to Kircher with a note explaining that it had come from Egypt, and asking Kircher for a translation: which Kircher, reportedly, produced at once. It has been speculated that these were both cryptographic tricks played on Kircher to make him look foolish: but the Voynich manuscript is on such a vastly different scale to a few signs in a letter that this seems somewhat out of scale for such an endeavor.

Raphael Mnishovsky, the friend of Marci who was the reputed source of Bacon's story, was himself a cryptographer (among many other things) and apparently invented a cipher that he claimed was uncrackable (ca. 1618). This has led to the speculation that Mnishovsky might have produced the Voynich manuscript as a practical demonstration of his cipher and made Baresch his unwitting test subject. Indeed, the disclaimer in the Voynich manuscript cover letter could mean that Marci suspected some kind of deception was at play. However, there is no definite evidence for this theory.[citation needed]

In his 2006 book, Nick Pelling proposed that the Voynich manuscript was written by the 15th century North Italian architect Antonio Averlino (also known as "Filarete"), a theory broadly consistent with the radiocarbon dating.[9]

Richard SantaColoma has speculated that the Voynich Manuscript may be connected to Cornelis Drebbel, initially suggesting it was Drebbel's cipher notebook on microscopy and alchemy, and then later hypothesising it is a fictional "tie-in" to Francis Bacon's utopian novel New Atlantis in which some Drebbel-related items (submarine, perpetual clock) are said to appear.[28]

Language hypotheses

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2011) |

There are many hypotheses about the Voynich manuscript's "language":

Ciphers

According to the "letter-based cipher" theory, the Voynich manuscript contains a meaningful text in some European language that was intentionally rendered obscure by mapping it to the Voynich manuscript "alphabet" through a cipher of some sort—an algorithm that operated on individual letters. This has been the working hypothesis for most twentieth-century deciphering attempts, including an informal team of NSA cryptographers led by William F. Friedman in the early 1950s.[citation needed]

The main argument for this theory is that the use of a strange alphabet by a European author is awkward to explain except as an attempt to hide information. Indeed, even Roger Bacon knew about ciphers, and the estimated date for the manuscript roughly coincides with the birth of cryptography in Europe as a relatively systematic discipline.[citation needed]

The counterargument is that almost all cipher systems consistent with that era fail to match what we see in the Voynich manuscript. For example, simple monoalphabetic ciphers can be excluded because the distribution of letter frequencies does not resemble that of any common language; while the small number of different letter-shapes used implies that we can rule out nomenclator ciphers and homophonic ciphers, because these typically employ larger cipher alphabets. Similarly, polyalphabetic ciphers, first invented by Alberti in the 1460s and including the later Vigenère cipher, usually yield ciphertexts where all cipher shapes occur with roughly equal probability, quite unlike the language-like letter distribution the Voynich Manuscript appears to have.[citation needed]

However, the presence of many tightly grouped shapes in the Voynich manuscript (such as "or", "ar", "ol", "al", "an", "ain", "aiin", "air", "aiir", "am", "ee", "eee", etc.) does suggest that its cipher system may make use of a "verbose cipher", where single letters in a plaintext get enciphered into groups of fake letters. For example, the first two lines of page f15v (seen above) contain "or or or" and "or or oro r", which strongly resemble how Roman numbers such as "CCC" or "XXXX" would look if verbosely enciphered. Yet, even though verbose encipherment is arguably the best match, it still falls well short of being able to explain all of the Voynich manuscript's odd textual properties.[citation needed]

It is also entirely possible that the encryption system started from a fundamentally simple cipher and then augmented it by adding nulls (meaningless symbols), homophones (duplicate symbols), transposition cipher (letter rearrangement), false word breaks, and so on.[citation needed]

Codes

According to the "codebook cipher" theory, the Voynich manuscript "words" would actually be codes to be looked up in a "dictionary" or codebook. The main evidence for this theory is that the internal structure and length distribution of many words are similar to those of Roman numerals—which, at the time, would be a natural choice for the codes. However, book-based ciphers are viable only for short messages, because they are very cumbersome to write and to read.[citation needed]

Steganography

This theory holds that the text of the Voynich manuscript is mostly meaningless, but contains meaningful information hidden in inconspicuous details—e.g., the second letter of every word, or the number of letters in each line. This technique, called steganography, is very old and was described by Johannes Trithemius in 1499. Though it has been speculated that the plain text was to be extracted by a Cardan grille of some sort, this seems somewhat unlikely because the words and letters are not arranged on anything like a regular grid. Still, steganographic claims are hard to prove or disprove, since stegotexts can be arbitrarily hard to find. An argument against steganography is that having a cipher-like cover text highlights the very existence of the secret message, which would be self-defeating: yet because the cover text no less resembles an unknown natural language, this argument is not hugely persuasive.[citation needed]

It has been suggested that the meaningful text could be encoded in the length or shape of certain pen strokes.[29][unreliable source?] There are indeed examples of steganography from about that time that use letter shape (italic vs. upright) to hide information. However, when examined at high magnification, the Voynich manuscript pen strokes seem quite natural, and substantially affected by the uneven surface of the vellum.[citation needed]

Natural language

Statistical analysis of the text reveals patterns similar to those of natural languages. For instance, the word entropy (about 10 bits per word) is similar to that of English or Latin texts.[30] In 2013, Diego Amancio et al argued that the Voynich manuscript "is mostly compatible with natural languages and incompatible with random texts".[31]

The linguist Jacques Guy once suggested that the Voynich manuscript text could be some little-known natural language, written in the plain with an invented alphabet. The word structure is similar to that of many language families of East and Central Asia, mainly Sino-Tibetan (Chinese, Tibetan, and Burmese), Austroasiatic (Vietnamese, Khmer, etc.) and possibly Tai (Thai, Lao, etc.). In many of these languages, the words have only one syllable; and syllables have a rather rich structure, including tonal patterns.[citation needed]

This theory has some historical plausibility. While those languages generally had native scripts, these were notoriously difficult for Western visitors. This difficulty motivated the invention of several phonetic scripts, mostly with Latin letters but sometimes with invented alphabets. Although the known examples are much later than the Voynich manuscript, history records hundreds of explorers and missionaries who could have done it—even before Marco Polo's thirteenth century journey, but especially after Vasco da Gama sailed the sea route to the Orient in 1499.[citation needed]

The main argument for this theory is that it is consistent with all statistical properties of the Voynich manuscript text which have been tested so far, including doubled and tripled words (which have been found to occur in Chinese and Vietnamese texts at roughly the same frequency as in the Voynich manuscript). It also explains the apparent lack of numerals and Western syntactic features (such as articles and copulas), and the general inscrutability of the illustrations. Another possible hint is two large red symbols on the first page, which have been compared to a Chinese-style book title, inverted and badly copied. Also, the apparent division of the year into 360 days (rather than 365 days), in groups of 15 and starting with Pisces, are features of the Chinese agricultural calendar (jie qi, 節氣). The main argument against the theory is the fact that no one (including scholars at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing) has been able to find any clear examples of Asian symbolism or Asian science in the illustrations.[citation needed]

In 1976, James R Child of the National Security Agency, a linguist of Indo-European languages, proposed that the manuscript was written in a "hitherto unknown North Germanic dialect".[32] He identified in the manuscript a "skeletal syntax several elements of which are reminiscent of certain Germanic languages", while the content itself is expressed using "a great deal of obscurity".[33]

In late 2003, Zbigniew Banasik of Poland proposed that the manuscript is plaintext written in the Manchu language and gave a proposed piecemeal translation of the first page of the manuscript.[34][unreliable source?]

In February 2014, Professor Stephen Bax of the University of Bedfordshire made public his research into using "bottom up" methodology to understand the manuscript. His method involves looking for and translating proper nouns, in association with relevant illustrations, in the context of other languages of the same time period. A paper he posted online offers tentative translation of 14 characters and 10 words.[35][36][37][38] He suggests the text is a treatise on nature written in a natural language, rather than a code.

In 2014, Arthur O. Tucker and Rexford H. Talbert published a paper claiming a positive identification of 37 plants, 6 animals, and 1 mineral referenced in the manuscript to plant drawings in the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis or Badianus manuscript, a fifteenth century Aztec herbal.[39] They argue that these were from Colonial New Spain and represented the Nahuatl language, and date the manuscript to between 1521 (the date of the Conquest) to ca. 1576, in contradiction of radiocarbon dating evidence of the vellum and many other elements of the manuscript. The analysis has been criticized by other Voynich Manuscript researchers,[40] pointing out that—among other things—a skilled forger could construct plants that have a passing resemblance to existing plants that were heretofore undiscovered.[41]

Constructed language

The peculiar internal structure of Voynich manuscript words led William F. Friedman to conjecture that the text could be a constructed language. In 1950, Friedman asked the British army officer John Tiltman to analyze a few pages of the text, but Tiltman did not share this conclusion. In a paper in 1967, Brigadier Tiltman said,

"After reading my report, Mr. Friedman disclosed to me his belief that the basis of the script was a very primitive form of synthetic universal language such as was developed in the form of a philosophical classification of ideas by Bishop Wilkins in 1667 and Dalgarno a little later. It was clear that the productions of these two men were much too systematic, and anything of the kind would have been almost instantly recognisable. My analysis seemed to me to reveal a cumbersome mixture of different kinds of substitution."[11]

The concept of an artificial language is quite old, as attested by John Wilkins's Philosophical Language (1668), but still postdates the generally accepted origin of the Voynich manuscript by two centuries. In most known examples, categories are subdivided by adding suffixes; as a consequence, a text in a particular subject would have many words with similar prefixes—for example, all plant names would begin with similar letters, and likewise for all diseases, etc. This feature could then explain the repetitious nature of the Voynich text. However, no one has been able yet to assign a plausible meaning to any prefix or suffix in the Voynich manuscript.[42]

Hoax

The bizarre features of the Voynich manuscript text (such as the doubled and tripled words), and the suspicious contents of its illustrations support the idea that the manuscript is a hoax. In other words, if no one is able to extract meaning from the book, then perhaps this is because the document contains no meaningful content in the first place. Various hoax theories have been proposed over time.

In 2003, computer scientist Gordon Rugg showed that text with characteristics similar to the Voynich manuscript could have been produced using a table of word prefixes, stems, and suffixes, which would have been selected and combined by means of a perforated paper overlay.[43][44] The latter device, known as a Cardan grille, was invented around 1550 as an encryption tool, more than 100 years after the estimated creation date of the Voynich manuscript. Some maintain that the similarity between the pseudo-texts generated in Gordon Rugg's experiments and the Voynich manuscript is superficial, and the grille method could be used to emulate any language to a certain degree.[45]

In April 2007, a study by Austrian researcher Andreas Schinner published in Cryptologia supported the hoax hypothesis.[46] Schinner showed that the statistical properties of the manuscript's text were more consistent with meaningless gibberish produced using a quasi-stochastic method such as the one described by Rugg, than with Latin and medieval German texts.[46]

The argument for authenticity is that the manuscript appears too sophisticated to be a hoax. While hoaxes of the period tended to be quite crude, the Voynich manuscript exhibits many subtle characteristics which show up only after careful statistical analysis. The question then arises as to why the author would employ such a complex and laborious forging algorithm in the creation of a simple hoax, if no one in the expected audience (that is, the creator's contemporaries) could tell the difference. Marcelo Montemurro, a theoretical physicist from the University of Manchester who spent years analysing the linguistic patterns in the Voynich manuscript, found semantic networks such as content-bearing words occurring in a clustered pattern, and new words being used when there was a shift in topic.[47] With this evidence, he believes it unlikely that these features were simply "incorporated" into the text to make a hoax more realistic, as most of the required academic knowledge of these structures did not exist at the time the Voynich manuscript was created. These fine touches require much more work than would have been necessary for a simple forgery, and some of the complexities are only visible with modern tools.[48]

Glossolalia

In their 2004 book, Gerry Kennedy and Rob Churchill hint at the possibility that the Voynich manuscript may be a case of glossolalia, channeling, or outsider art.[49]

If this is true, then the author felt compelled to write large amounts of text in a manner which somehow resembles stream of consciousness, either because of voices heard, or because of an urge. While in glossolalia this often takes place in an invented language (usually made up of fragments of the author's own language), invented scripts for this purpose are rare. Kennedy and Churchill use Hildegard von Bingen's works to point out similarities between the illustrations she drew when she was suffering from severe bouts of migraine—which can induce a trance-like state prone to glossolalia—and the Voynich manuscript. Prominent features found in both are abundant "streams of stars", and the repetitive nature of the "nymphs" in the biological section.[citation needed]

The theory is virtually impossible to prove or disprove, short of deciphering the text; Kennedy and Churchill are themselves not convinced of the hypothesis, but consider it plausible. In the culminating chapter of their work, Kennedy states his belief that it is a hoax or forgery. Churchill acknowledges the possibility that the manuscript is a synthetic forgotten language (as advanced by Friedman), or a forgery, to be preeminent theories. However he concludes that if the manuscript is genuine, mental illness or delusion seems to have affected the author.[49]

Historical decipherment claims

Since the manuscript's modern rediscovery in 1912 there have been a number of claims of successful decipherment.

William Romaine Newbold

One of the earliest efforts to unlock the book's secrets (and the first of many premature claims of decipherment) was made in 1921 by William Romaine Newbold of the University of Pennsylvania. His singular hypothesis held that the visible text is meaningless itself, but that each apparent "letter" is in fact constructed of a series of tiny markings only discernible under magnification. These markings were supposed to be based on ancient Greek shorthand, forming a second level of script that held the real content of the writing. Newbold claimed to have used this knowledge to work out entire paragraphs proving the authorship of Bacon and recording his use of a compound microscope four hundred years before van Leeuwenhoek. A circular drawing in the "astronomical" section depicts an irregularly shaped object with four curved arms, which Newbold interpreted as a picture of a galaxy, which could only be obtained with a telescope.[11] Similarly, he interpreted other drawings as cells seen through a microscope.

However, Newbold's analysis has since been dismissed as overly speculative[50] after John Matthews Manly of the University of Chicago pointed out serious flaws in his theory. Each shorthand character was assumed to have multiple interpretations, with no reliable way to determine which was intended for any given case. Newbold's method also required rearranging letters at will until intelligible Latin was produced. These factors alone ensure the system enough flexibility that nearly anything at all could be discerned from the microscopic markings. Although evidence of micrography using the Hebrew language can be traced as far back as the ninth century,[51] it is nowhere near as compact or complex as the shapes Newbold made out. Close study of the manuscript revealed the markings to be artifacts caused by the way ink cracks as it dries on rough vellum. Perceiving significance in these artifacts can be attributed to pareidolia. Thanks to Manly's thorough refutation, the micrography theory is now generally disregarded.[52]

Joseph Martin Feely

In 1943, Joseph Martin Feely published Roger Bacon's Cipher: The Right Key Found, in which he claimed that the book was a scientific diary. Feely's method posited that the text was a highly abbreviated medieval Latin written with a simple substitution cipher. He also claimed that the writer of the manuscript was Roger Bacon.[16]

Leonell C Strong

Leonell C. Strong, a cancer research scientist and amateur cryptographer, believed that the solution to the Voynich manuscript was a "peculiar double system of arithmetical progressions of a multiple alphabet". Strong claimed that the plaintext revealed the Voynich manuscript to be written by the 16th-century English author Anthony Ascham, whose works include A Little Herbal, published in 1550. The main argument against this theory is that its claimed offsetting cryptography runs counter to all the complex internal structures presented by the text.[citation needed]

Robert S Brumbaugh

Robert Brumbaugh, a professor of medieval philosophy at Yale University, claimed that the manuscript was a forgery intended to fool Emperor Rudolf II into purchasing it. The text is Latin, but enciphered with a complex, two–step method.[16]

John Stojko

In 1978, John Stojko published Letters to God's Eye[53] in which he claimed that the Voynich Manuscript was a series of letters written in vowelless Ukrainian.[54] However, the date Stojko gives for the letters, the lack of relation between the text and the images, and the general looseness in the method of decryption all speak against his theory.[54]

Leo Levitov

Leo Levitov proposed in his 1987 book, Solution of the Voynich Manuscript: A Liturgical Manual for the Endura Rite of the Cathari Heresy, the Cult of Isis,[55] that the manuscript is a handbook for the Cathar rite of Endura written in a Flemish based creole. He further claimed that Catharism was a survival of the cult of Isis.[56]

However, Levitov's decipherment has been refuted on several grounds, not least of being unhistorical. Levitov had a poor grasp on the history of the Cathar, and his depiction of Endura as an elaborate suicide ritual is at odds with surviving documents describing it as a fast.[56] Likewise, there is no known link between Catharism and Isis.

Cultural impact

Many books and articles have been written about the manuscript. The first facsimile edition was published in 2005, Le Code Voynich: the whole manuscript published with a short presentation in French.[57]

The manuscript has also inspired several works of fiction, including The Book of Blood and Shadow by Robin Wasserman, Time Riders: The Doomsday Code by Alex Scarrow, Codex by Lev Grossman, PopCo by Scarlett Thomas, Prime by Jeremy Robinson with Sean Ellis, The Sword of Moses (2013) by Dominic Selwood, The Return of the Lloigor by Colin Wilson, Datura, or a delusion we all see (Finnish version 2001) by Leena Krohn, "Assassin's Code" by Jonathan Maberry and "The Source" by Michael Cordy.

Between 1976 and 1978,[58] Italian artist Luigi Serafini created the Codex Seraphinianus containing false writing and pictures of imaginary plants, in a style reminiscent of the Voynich manuscript.[59][60][61]

Contemporary classical composer Hanspeter Kyburz's 1995 Chamber work The Voynich Cipher Manuscript, for chorus & ensemble is inspired by the manuscript.[62]

See also

- Asemic writing

- Automatic writing

- Beale ciphers

- Book of Soyga

- Codex Seraphinianus

- Copiale cipher

- False document

- False writing system

- Fictional language

- Oera Linda Book

- Rohonc Codex

- Rongorongo

- Undeciphered writing systems

References

- ^ a b c Steindl, Klaus; Sulzer, Andreas (2011). "The Voynich Code — The World's Mysterious Manuscript". Archived from the original (video) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Stolte, Daniel (February 10, 2011). "Experts determine age of book 'nobody can read'". PhysOrg. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Brumbaugh, Robert S. (1977). The World's Most Mysterious Manuscript. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ^ Hogenboom, Melissa, Mysterious Voynich manuscript has 'genuine message', BBC News, 21 June 2013, accessed 24 June 2013

- ^ Pelling, Nick. "Voynich theories". ciphermysteries.com. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ^ "MS 408". Yale Library. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- ^ "Voynich Manuscript". Beinecke Library. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shailor, Barbara A.,Beinecke MS 408, Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book And Manuscript Library, General Collection Of Rare Books And Manuscripts, Medieval And Renaissance Manuscripts, accessed 24 June 2013

- ^ a b Pelling, Nicholas John. "The Curse of the Voynich: The Secret History of the World's Most Mysterious Manuscript". Compelling Press, 2006. ISBN 0-9553160-0-6

- ^ a b c Barabe, Joseph G. (McCrone Associates) (April 1, 2009). "Materials analysis of the Voynich Manuscript" (PDF). Beinecke Library.

- ^ a b c d e f Tiltman, John H. (Summer 1967). "The Voynich Manuscript: "The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World"" (PDF). XII (3). NSA Technical Journal. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g Schmeh, Klaus (January–February 2011). "The Voynich Manuscript: The Book Nobody Can Read". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ^ Zandbergen, Rene. "Analysis Section ( 3/5 ) - Word structure". www.voynich.nu. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Friedman, Elizebeth. 1962. "The Most Mysterious MS. - Still an Enigma". Washington D.C. Post, 5 August, E1, E5. Quoted in Mary D'Imperio's "Elegant Enigma", p.27 (section 4.4)

- ^ Reeds, Jim (September 7, 1994). "William F. Friedman's Transcription of the Voynich Manuscript" (PDF). AT&T Bell Laboratories. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e D'Imperio, M.E. (1978). "The Voynich Manuscript: An Elegant Enigma" (PDF). National Security Agency. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Palmer, Sean B. (2004). "Voynich Manuscript: Months". Inamidst.com. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Palmer, Sean B. (2004). "Notes on f116v's Michitonese". Inamidst.com. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Gerry; Churchill, Rob (14 January 2011). The Voynich Manuscript: The Mysterious Code That Has Defied Interpretation for Centuries. Inner Traditions International, Limited. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-1-59477-854-4. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Voynich MS — Long tour: Known history of the manuscript". Voynich.nu. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Mysterious Voynich manuscript is genuine - Evidence in 2009 showing that the manuscript is indeed old as had been suspected Archived 2013-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "University of Arizona announcement of radiocarbon result".

- ^ Letter, Georg Baresch to Athanasius Kircher, 1639 Archives of the Pontificia Università Gregoriana in Rome, shelfmark APUG 557, fol. 353

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k John Schuster (27 April 2009). Haunting Museums. Tom Doherty Associates. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-1-4299-5919-3. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Philip Neal's analysis of Marci's grammar". Voynich Central. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ a b "Origin of the manuscript". Voynich MS. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ^ "The New Signature of Horczicky and the Comparison of them all". Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ H. Richard SantaColoma. "New Atlantis Voynich Theory". santa-coloma.net. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "Michael James Banks, A Search-Based Tool for the Automated Cryptoanalysis of Classical Ciphers" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Landini, Gabriel (October 2001). "Evidence of linguistic structure in the Voynich manuscript using spectral analysis". Cryptologia. 25 (4): 275–295. doi:10.1080/0161-110191889932. Retrieved 2006-11-06.

- ^ Amancio, Diego R.; Altmann, Eduardo G.; Rybski, Diego; Oliveira Jr, Osvaldo N.; Costa, Luciano da F. (July 2013). "Probing the statistical properties of unknown texts: application to the Voynich Manuscript". PLOS ONE. doi:10.1080/01611190601133539. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ^ Child, James R. (Summer 1976). "The Voynich Manuscript Revisited". XXI (3). NSA Technical Journal.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Child, Jim (2009-06-16). "Again, The Voynich Manuscript. 2007" (PDF). Web.archive.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-16. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ "Zbigniew Banasik's Manchu theory". Ic.unicamp.br. 2004-05-21. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ "600 year old mystery manuscript decoded by University of Bedfordshire professor". University of Bedfordshire. 2014-02-14. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ^ Bax, Stephen (2014-01-01). "A proposed partial decoding of the Voynich script" (PDF). Stephen Bax. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ^ "Breakthrough over 600-year-old mystery manuscript". BBC News Online. 2014-02-18. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ^ "British academic claims to have made a breakthrough in his quest to unlock the 600-year-old secrets of the mysterious Voynich Manuscript". The Independent. 2014-02-20. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ^ Tucker, Arthur O.; Talbert, Rexford H. (Winter 2013). "A Preliminary Analysis of the Botany, Zoology, and Mineralogy of the Voynich Manuscript". HerbalGram (100): 70–75.

- ^ Pelling, Nick (14 January 2014). "A Brand New New World / Nahuatl Voynich Manuscript Theory…". Cipher Mysteries. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (February 3, 2014). "Mexican plants could break code on gibberish manuscript". New Scientist. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- ^ Kahn, David (1967). The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing (1st ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 870–871.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Gordon Rugg. "Replicating the Voynich Manuscript". UK: Keele. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ McKie, Robin (25 January 2004). "Secret of historic code: it's gibberish". UK: The Observer. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ^ D'Agnese, Joseph. "Scientific Method Man". Wired, September 2004. Retrieved on March 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Andreas Schinner (April 2007). "The Voynich Manuscript: Evidence of the Hoax Hypothesis". Cryptologia. 31 (2): 95–107. doi:10.1080/01611190601133539. ISSN 0161-1194. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ Montemurro, Marcelo A.; Zanette, Damián H. (20 June 2013). "Keywords and Co-Occurrence Patterns in the Voynich Manuscript: An Information-Theoretic Analysis". PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e66344. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066344.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Melissa Hogenboom (22 June 2013). "Mysterious Voynich manuscript has 'genuine message'". BBC News. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ a b Gerry Kennedy, Rob Churchill (2004). The Voynich Manuscript. London: Orion. ISBN 0-7528-5996-X.

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania archives". Archives.upenn.edu. 1926-09-06. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ "Micrography:The Hebrew Word As Art". Jtsa.edu. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Kahn 1967, pp. 867–869

- ^ Stojko, John (1978). Letters to God's Eye: The Voynich Manuscript for the first time deciphered and translated into English. New York: Vantage Press.

- ^ a b Zandbergen, Rene. "Voynich MS - History of research of the MS". www.voynich.nu. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Levitov, Leo (1987). Solution of the Voynich Manuscript: A Liturgical Manual for the Endura Rite of the Cathari Heresy, the Cult of Isis. Laguna Hills, California: Aegean Park Press.

- ^ a b Stallings, Dennis. "Catharism, Levitov, and the Voynich Manuscript". http://ixoloxi.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Le Code Voynich, ed. Jean-Claude Gawsewitch, (2005) ISBN 2-35013-022-3

- ^ Corrias, Pino (February 5, 2006). "L'enciclopedia dell'altro mondo" (PDF) (in Italian). IT: La Repubblica: 39Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ "Codex Seraphinianus". rec.arts.books. Google. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ "Codex Seraphinianus: Some Observations". BG: Bas. 2004-09-29. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Berloquin, Pierre (2008). Hidden Codes & Grand Designs: Secret Languages from Ancient Times to Modern Day. Sterling. p. 300. ISBN 1-4027-2833-6. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2001/11/18/arts/music-a-metaphor-powerful-and-poetic.html

Further reading

- Manly, John Matthews (July 1921). "The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World: Did Roger Bacon Write It and Has the Key Been Found?". Harper's Monthly Magazine (143): 186–197.

- Voynich, Wilfrid Michael (1921). "A Preliminary Sketch of the History of the Roger Bacon Cipher Manuscript". Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 3 (43): 415–430.

- Newbold, William Romaine (1928). The Cipher of Roger Bacon. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Manly, John Matthews (1931). "Roger Bacon and the Voynich MS". Speculum. 6 (3): 345–391. doi:10.2307/2848508. JSTOR 2848508.

- Brumbaugh, Robert S. (1978). The Most Mysterious Manuscript: The Voynich 'Roger Bacon' Cipher Manuscript. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-0808-8.

- D'Imperio, M. E. (1978). The Voynich Manuscript: An Elegant Enigma. Laguna Hills, CA: Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-038-7.

- D'Imperio, M. E. (1978). The Voynich Manuscript: An Elegant Enigma (PDF). Fort George G. Meade, MD: National Security Agency/Central Security Service. OCLC 50929259. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- Stojko, John (1978). Letters to God's Eye. New York: Vantage Press. ISBN 0-533-04181-3.

- Levitov, Leo (1987). Solution of the Voynich Manuscript: A Liturgical Manual for the Endura Rite of the Cathari Heresy, the Cult of Isis. Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-148-0.

- Pérez-Ruiz, Mario M. (2003). El Manuscrito Voynich (in Spanish). Barcelona: Océano Ambar. ISBN 84-7556-216-7.

- Kennedy, Gerry; Churchill, Rob (2004). The Voynich Manuscript The Unsolved Riddle of an Extraordinary Book Which Has Defied Interpretation for Centuries. London: Orion. ISBN 0-7528-5996-X.

- Goldstone, Lawrence; Goldstone, Nancy (2005). The Friar and the Cipher: Roger Bacon and the Unsolved Mystery of the Most Unusual Manuscript in the World. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-7679-1473-2.

- Pelling, Nicholas (2006). The Curse of the Voynich: The Secret History of the World's Most Mysterious Manuscript. Surbiton, Surrey: Compelling Press. ISBN 0-9553160-0-6.

- Violat-Bordonau, Francisco (2006). El ABC del Manuscrito Voynich (in Spanish). Cáceres, Spain: Ed. Asesores Astronómicos Cacereños.

- Foti, Claudio (2010). Il Codice Voynich (in Italian). Roma: Eremon Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-89713-17-4.

- Amancio, Diego R. (2013). "Probing the Statistical Properties of Unknown Texts: Application to the Voynich Manuscript". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e67310. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067310.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Montemurro, Marcelo A.; Zanette, Damián H. (2013). "Keywords and Co-Occurrence Patterns in the Voynich Manuscript: An Information-Theoretic Analysis". PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e66344. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066344.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Stollznow, Karen (2014). "The Mysterious Voynich Manuscript". Skeptic Magazine. 19 (2). Retrieved 20 August 2015.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- The Voynich Manuscript from the digital collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

- The Voynich Manuscript at the Internet Archive

- complete pdf (53 MB)

- René Zandbergen's Voynich Manuscript Page about the Voynich Manuscript, including a Voynich MS - Pages / Folios gallery, and a bibliography

- Cipher Mysteries, Nick Pelling's historical cipher research site

- Voynich Manuscript Mailing List HQ

- Voynich Manuscript Bibliography by Jim Reeds

- Nature news article: World's most mysterious book may be a hoax A summary of Gordon Rugg's paper directed towards a more general audience

- Gordon Rugg, "The Mystery of the Voynich Manuscript", Scientific American, June 21, 2004

- Antoine Casanova, "méthodes d’analyse du langage crypté: Une contribution à l’étude du manuscrit de Voynich", 'Université PARIS VIII', 19 mars 1999

- The Voynich Code: The World's Mysterious Manuscript, an Austrian documentary film on the manuscript

- The Unread: The Mystery of the Voynich Manuscript from The New Yorker

- Voynich, a public-domain font based on Voynich 101, which was used to digitally transcribe the text