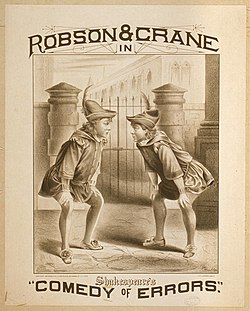

The Comedy of Errors

The Comedy of Errors is one of William Shakespeare's early plays. It is his shortest and one of his most farcical comedies, with a major part of the humour coming from slapstick and mistaken identity, in addition to puns and word play. It has been adapted for opera, stage, screen and musical theatre numerous times worldwide. In the centuries following its premiere, the play's title has entered the popular English lexicon as an idiom for "an event or series of events made ridiculous by the number of errors that were made throughout".[1]

Set in the Greek city of Ephesus, The Comedy of Errors tells the story of two sets of identical twins who were accidentally separated at birth. Antipholus of Syracuse and his servant, Dromio of Syracuse, arrive in Ephesus, which turns out to be the home of their twin brothers, Antipholus of Ephesus and his servant, Dromio of Ephesus. When the Syracusans encounter the friends and families of their twins, a series of wild mishaps based on mistaken identities lead to wrongful beatings, a near-seduction, the arrest of Antipholus of Ephesus, and false accusations of infidelity, theft, madness, and demonic possession.

Characters

[edit]

- Solinus – Duke of Ephesus

- Aegeon – A merchant of Syracuse – father of the Antipholus twins

- Emilia – an Abbess – Antipholus' lost mother – wife to Aegeon

- Antipholus of Ephesus and Antipholus of Syracuse – twin brothers, sons of Aegeon and Emilia

- Dromio of Ephesus and Dromio of Syracuse – twin brothers, bondmen, each serving his respective Antipholus

- Adriana – wife of Antipholus of Ephesus

- Luciana – Adriana's sister, love interest of Antipholus of Syracuse

- Nell – kitchen wench/maid to Adriana, Wife of Dromio of Ephesus

- Luce – a witty and vivacious servant in the household of Antipholus of Syracuse

- Balthazar – a merchant

- Angelo – a goldsmith

- Courtesan

- First merchant – friend to Antipholus of Syracuse

- Second merchant – to whom Angelo is in debt

- Doctor Pinch – a conjuring schoolmaster

- Gaoler, Headsman, Officers, and other Attendants

Synopsis

[edit]Act I

[edit]Because a law forbids merchants from Syracuse from entering Ephesus, elderly Syracusan trader Aegeon faces execution when he is discovered in the city. He can only escape by paying a fine of a thousand marks. He tells his sad story to Solinus, Duke of Ephesus. In his youth, Aegeon married and had twin sons. On the same day, a poor woman without a job also gave birth to twin boys, and he purchased these as servants to his sons. Soon afterward, the family made a sea voyage and was hit by a tempest. Aegeon lashed himself to the main-mast with one son and one servant, and his wife took the other two infants. His wife was rescued by one boat, Aegeon by another. Aegeon never again saw his wife or the children with her. Recently his son Antipholus, now grown, and his son's servant, Dromio, left Syracuse to find their brothers. When Antipholus did not return, Aegeon set out in search of him. The Duke is moved by this story and grants Aegeon one day to pay his fine.

That same day, Antipholus arrives in Ephesus, searching for his brother. He sends Dromio to deposit some money at The Centaur, an inn. He is confounded when the identical Dromio of Ephesus appears almost immediately, denying any knowledge of the money and asking him home to dinner, where his wife is waiting. Antipholus, thinking his servant is making insubordinate jokes, beats Dromio of Ephesus.

Act II

[edit]Dromio of Ephesus returns to his mistress, Adriana, saying that her "husband" refused to come back to his house, and even pretended not to know her. Adriana, concerned that her husband's eye is straying, takes this news as confirmation of her suspicions.

Antipholus of Syracuse, who complains "I could not speak with Dromio since at first, I sent him from the mart," meets up with Dromio of Syracuse who now denies making a "joke" about Antipholus having a wife. Antipholus begins beating him. Suddenly, Adriana rushes up to Antipholus of Syracuse and begs him not to leave her. The Syracusans cannot but attribute these strange events to witchcraft, remarking that Ephesus is known as a warren for witches. Antipholus and Dromio go off with this strange woman, the one to eat dinner and the other to keep the gate.

Act III

[edit]Inside the house, Antipholus of Syracuse discovers that he is very attracted to his "wife's" sister, Luciana, telling her "train me not, sweet mermaid, with thy note / To drown me in thy sister's flood of tears." She is flattered by his attention but worried about their moral implications. After she exits, Dromio of Syracuse announces that he has discovered that he has a wife: Nell, a hideous kitchen-maid. The Syracusans decide to leave as soon as possible, and Dromio runs off to make travel plans. Antipholus of Syracuse is then confronted by Angelo of Ephesus, a goldsmith, who claims that Antipholus ordered a chain from him. Antipholus is forced to accept the chain, and Angelo says that he will return for payment.

Antipholus of Ephesus returns home for dinner and is enraged to find that he is rudely refused entry to his own house by Dromio of Syracuse, who is keeping the gate. He is ready to break down the door, but his friends persuade him not to make a scene. He decides, instead, to dine with a courtesan.

Act IV

[edit]Antipholus of Ephesus dispatches Dromio of Ephesus to purchase a rope so that he can beat his wife Adriana for locking him out, then is accosted by Angelo, who tells him "I thought to have ta'en you at the Porpentine" and asks to be reimbursed for the chain. He denies ever seeing it and is promptly arrested. As he is being led away, Dromio of Syracuse arrives, whereupon Antipholus dispatches him back to Adriana's house to get money for his bail. After completing this errand, Dromio of Syracuse mistakenly delivers the money to Antipholus of Syracuse. The Courtesan spies Antipholus wearing the gold chain, and says he promised it to her in exchange for her ring. The Syracusans deny this and flee. The Courtesan resolves to tell Adriana that her husband is insane. Dromio of Ephesus returns to the arrested Antipholus of Ephesus, with the rope. Antipholus is infuriated. Adriana, Luciana, and the Courtesan enter with a conjurer named Pinch, who tries to exorcize the Ephesians, who are bound and taken to Adriana's house. The Syracusans enter, carrying swords, and everybody runs off for fear: believing that they are the Ephesians, out for vengeance after somehow escaping their bonds.

Act V

[edit]Adriana reappears with henchmen, who attempt to bind the Syracusans. They take sanctuary in a nearby priory, where the Abbess resolutely protects them. Suddenly, the Abbess enters with the Syracusan twins, and everyone begins to understand the confused events of the day. Not only are the two sets of twins reunited, but the Abbess reveals that she is Aegeon’s wife, Emilia. The Duke pardons Aegeon. All exit into the abbey to celebrate the reunification of the family.

Text and date

[edit]

The play is a modernised adaptation of Menaechmi by Plautus. As William Warner's translation of the classical drama was entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 10 June 1594, published in 1595, and dedicated to Lord Hunsdon, the patron of the Lord Chamberlain's Men, it has been supposed that Shakespeare might have seen the translation in manuscript before it was printed – though it is equally possible that he knew the play in the original Latin.

The play contains a topical reference to the wars of succession in France, which would fit any date from 1589 to 1595. Charles Whitworth argues that The Comedy of Errors was written "in the latter part of 1594" on the basis of historical records and textual similarities with other plays Shakespeare wrote around this time.[2] The play was not published until it appeared in the First Folio in 1623.[inconsistent]

Analysis and criticism

[edit]For centuries, scholars have found little thematic depth in The Comedy of Errors. Harold Bloom, however, wrote that it "reveals Shakespeare's magnificence at the art of comedy",[3] and praised the work as showing "such skill, indeed mastery – in action, incipient character, and stagecraft – that it far outshines the three Henry VI plays and the rather lame comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona".[4] Stanley Wells also referred to it as the first Shakespeare play "in which mastery of craft is displayed".[5] The play was not a particular favourite on the eighteenth-century stage because it failed to offer the kind of striking roles that actors such as David Garrick could exploit.

The play was particularly notable in one respect. In the earlier eighteenth century, some critics followed the French critical standard of judging the quality of a play by its adherence to the classical unities, as specified by Aristotle in the fourth century BC. The Comedy of Errors and The Tempest were the only two of Shakespeare's plays to comply with this standard.[6]

Law professor Eric Heinze, however, argues that particularly notable in the play is a series of social relationships, which is in crisis as it sheds its feudal forms and confronts the market forces of early modern Europe.[7]

Performance

[edit]Two early performances of The Comedy of Errors are recorded. One, by "a company of base and common fellows", is mentioned in the Gesta Grayorum ("The Deeds of Gray") as having occurred in Gray's Inn Hall on 28 December 1594 during the inn's revels. The second also took place on "Innocents' Day", but ten years later: 28 December 1604, at Court.[8]

Adaptations

[edit]

Theatrical

[edit]Like many of Shakespeare's plays, The Comedy of Errors was adapted and rewritten extensively, particularly from the 18th century on, with varying reception from audiences.

Classical adaptations

[edit]- Every Body Mistaken is a 1716 "revival" and directorial adaptation of Shakespeare's play by an anonymous author.[9]

- See If You Like It; or, 'Tis All a Mistake, an anonymous adaptation staged in 1734 at Covent Garden, performed in two acts with text from Plautus and Shakespeare. Shakespeare purists considered it to be the "worst alteration" available.[10][11]

- The Twins, by Thomas Hull produced an adaptation for Covent Garden in 1739, where Hull played Aegon. This production was more faithful to Shakespeare's text, and played for several years.[10] This adaptation was performed only once in 1762, and was published in 1770. Hull adapted the play a second time as The Comedy of Errors. With Alterations from Shakespeare. This version was staged frequently from 1779 onward, and was published in 1793.[11] Hull added songs, intensified the love interest, and elaborated the recognition scene. He also expanded roles for women, including Adriana's cousin Hermia, who sang various songs.[9]

- The Twins; or, Which is Which? A Farce. In Three Acts by William Woods, published in 1780. Produced at the Theatre-Royal, Edinburgh.[11] This adaptation reduced the play to a three-act farce, apparently believing that a longer run time should "pall upon an audience." John Philip Kemble (see below) seemed to have extended and based his own adaptation upon The Twins.[9]

- Oh! It's Impossible by John Philip Kemble, was produced in 1780. This adaptation caused a stir by casting the two Dromios as black-a-moors.[12] It was acted in York, but not printed.[13] Later, nearly 20 years after slavery had been abolished within British domains, James Boaden wrote, "I incline to think [Kemble's] maturer judgement would certainly have consigned the whole impression to the flames.")[14]

Modern adaptations

[edit]- The Flying Karamazov Brothers performed a unique adaptation, produced by Robert Woodruff, first at the Goodman Theater in Chicago in 1983, and then again in 1987 at New York's Vivian Beaumont Theater in Lincoln Center. This latter presentation was filmed and aired on MTV and PBS.[15]

- The Comedy of Errors adapted and directed by Sean Graney in 2010 updated Shakespeare's text to modern language, with occasional Shakespearean text, for The Court Theatre. The play appears to be more of a "translation" into modern-esque language, than a reimagination.[16] The play received mixed reviews, mostly criticizing Graney's modern interpolations and abrupt ending.[17]

- 15 Villainous Fools, written and performed by Olivia Atwood and Maggie Seymour, a two-woman clown duo, produced by The 601 Theatre Company.[18][19] The play was performed several times, premiering in 2015 at Bowdoin College, before touring fringe festivals including Portland, San Diego, Washington, DC, Providence, and New York City. Following this run, the show was picked up by the People's Improv Theater for an extended run.[20] While the play included pop culture references and original raps, it kept true to Shakespeare's text for the characters of the Dromios.[21]

- A Comedy of Heirors, or The Imposters by feminist verse playwright, Emily C. A. Snyder, performed a staged reading through Turn to Flesh Productions[22] in 2017, featuring Abby Wilde as Glorielle of Syracuse. The play received acclaim, being named a finalist with the American Shakespeare Center, as part of the Shakespeare's New Contemporaries program,[23] as well as "The Top 15 NYC Plays of '17" by A Work Unfinishing.[24] The play focuses on two sets of female twins, who also interact with Shakespeare's Antipholi. The play is in conversation with several of Shakespeare's comedies, including characters from The Comedy of Errors, Twelfth Night, As You Like It, and Much Ado About Nothing.

Opera

[edit]- On 27 December 1786, the opera Gli equivoci by Stephen Storace received its première at the Burgtheater in Vienna. The libretto, by Lorenzo da Ponte, Mozart's frequent librettist, worked off a French translation of Shakespeare's play, follows the play's plot fairly closely, though some characters were renamed, Aegeon and Emilia are cut, and Euphemio (previously Antipholus) and Dromio are shipwrecked on Ephesus.[25][26]

- Frederic Reynolds staged an operatic version in 1819, with music by Henry Bishop supplemented lyrics from various Shakespeare plays, and sonnets set to melodies by Mozart, Thomas Arne, and others.[9] The opera was performed at Covent Gardens under Charles Kemble's management. The opera included several additional scenes from the play, which were considered necessary for the sake of introducing songs. The same operatic adaptation was revived in 1824 for Drury Lane.[10]

- Various other adaptations were performed down to 1855 when Samuel Phelps revived the Shakespearean original at Sadler's Wells Theatre.[27]

- The Czech composer Iša Krejčí's 1943 opera Pozdvižení v Efesu (Turmoil in Ephesus) is based on the play.[28]

Musicals

[edit]The play has been adapted as a musical several times, frequently by inserting period music into the light comedy. Some musical adaptations include a Victorian musical comedy (Arts Theatre, Cambridge, England, 1951), Brechtian folk opera (Arts Theatre, London, 1956), and a two-ring circus (Delacorte Theater, New York, 1967).

Fully original musical adaptations include:

- The Boys from Syracuse, composed by Richard Rodgers and lyrics by Lorenz Hart. The play premiered on Broadway in 1938 and Off-Broadway in 1963, with later productions including a West End run in 1963 and in a Broadway revival in 2002. A film adaptation was released in 1940.

- A New Comedy of Errors, or Too Many Twins (1940), adapted from Plautus, Shakespeare and Molière, staged in modern dress at London's Mercury Theatre.[9][29]

- The Comedy of Errors (1972) adaptation by James McCloskey, music and lyrics by Bruce Kimmel. Premiered at Los Angeles City College and went on to the American College Theatre Festival.

- The Comedy of Errors is a musical with book and lyrics by Trevor Nunn, and music by Guy Woolfenden. It was produced for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1976, winning the Laurence Olivier Award for best musical on its transfer to the West End in 1977.

- Oh, Brother! is a musical comedy in one act, with music by Michael Valenti and books and lyrics by Donald Driver, which premiered at ANTA Theatre in 1981, also directed by Driver. The musical takes place during a revolution in an oil rich Middle Eastern country on the Persian Gulf in a quaint resort town where its populace of merchants and revolutionaries mix Eastern tradition with Western consumerism.[30] The New York Times gave it a poor review, criticising Driver's heavy handedness, while praising some of the music and performances.[31]

- The Bomb-itty of Errors, a one-act hip-hop musical adaptation, by Jordan Allen-Dutton, Jason Catalano, Gregory J. Qaiyum, Jeffrey Qaiyum, and Erik Weinner, won 1st Prize at HBO's Comedy Festival and was nominated opposite Stephen Sondheim for the Best Lyrics Drama Desk Award in 2001.[32]

- In 1940 the film The Boys from Syracuse was released, starring Alan Jones and Joe Penner as Antipholus and Dromio. It was a musical, loosely based on The Comedy of Errors.

Novel

[edit]In India, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar adapted Shakespeare's play in his Bengali novel Bhranti Bilash (1869). Vidyasagar's efforts were part of the process of championing Shakespeare and the Romantics during the Bengal Renaissance.[33][34]

Film

[edit]The film Our Relations (1936) starring Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, was adapted from the W. W. Jacobs story "The Money Box", but there are no twins in the Jacobs story. Our Relations owes its central conceit to The Comedy of Errors.[original research?] As in the Shakespeare play, the story revolves around the confusion of two pairs of identical twins: one set of Laurel brothers named "Stan" and "Alf", and one set of Hardy brothers named "Oliver" and "Bert". Stan and Oliver think Alf and Bert were killed at sea. As the story opens, Alf and Bert have just arrived via ship at the same seaport where, unbeknownst to them, their married twin brothers Stan and Oliver live.[citation needed] One nod to the movie's inspiration is a running gag: whenever Stan and Ollie say the same thing at the same time, they immediately perform a childhood ritual that begins: "Shakespeare...Longfellow..."[original research?]

The Three Stooges film A Merry Mix Up (1957) starring Moe Howard, Larry Fine and Joe Besser expands the confusion by telling the story of three sets of identical triplets: Bachelors Moe, Larry and Joe; husbands Max, Louie and Jack; and newly-engaged brothers Morris, Luke and Jeff. The triplets can only be distinguished by their choices of neckties, bow ties, or no tie at all.[citation needed]

The film Start the Revolution Without Me (1970) starring Gene Wilder and Donald Sutherland involves two pairs of twins, one of each of which is switched at birth; one set is raised in an aristocratic, the other in a peasant family, who meet during the French Revolution.

The film Big Business (1988) is a modern take on The Comedy of Errors, with female twins instead of male. Bette Midler and Lily Tomlin star in the film as two sets of twins separated at birth, much like the characters in Shakespeare's play.

The short film The Complete Walk: The Comedy of Errors was made in 2016 and starred Phil Davis, Omid Djalili and Boothby Graffoe.

Indian cinema has made nine films based on the play:

- Bhrantibilas (1963 Bengali film) starring Uttam Kumar

- Do Dooni Char starring Kishore Kumar

- Angoor starring Sanjeev Kumar

- Oorantha Golanta starring Chandra Mohan

- A movie in the Kannada language titled Ulta Palta starring Ramesh Aravind

- A movie in the Telugu language titled Ulta Palta starring Rajendra Prasad

- A movie in the Tamil language titled Ambuttu Imbuttu Embuttu

- A movie in the Tulu language titled Aamait Asal Eemait Kusal starring Naveen D Padil

- Double Di Trouble (2014 Punjabi Film) directed by Smeep Kang and starring Dharmendra, Gippy Grewal

- Local Kung Fu 2 (2017 Assamese martial arts film)

- 2022 movie in Hindi language titled Cirkus starring Ranveer Singh

Television

[edit]- Roger Daltrey played both Dromios in the BBC complete works series directed by James Cellan Jones in 1983.

- A two-part TV adaptation was produced in 1978 in the USSR, with a Russian–Georgian cast of notable stage actors.

- The Inside No. 9 episode "Zanzibar" (season 4, episode 1) was based on The Comedy of Errors

- Season 13 Episode 4 of Bob's Burgers: 'Comet-y of Errors' is also a reference to Shakespeare's play.

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of 'Comedy of Errors'". merriam-webster.com. 24 March 2024.

- ^ Charles Walters Whitworth, ed., The Comedy of Errors, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003; pp. 1–10. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Bloom, Harold, ed. (2010). The Comedy of Errors. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438134406.

- ^ Bloom, Harold. "Shakespeare: The Comedy of Errors". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Billington, Michael (2 April 2014). "Best Shakespeare productions: The Comedy of Errors". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2010). Marson, Janyce (ed.). The Comedy of Errors. Bloom's Literary Criticism. New York: Infobase. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-60413-720-0.

It is noteworthy that The Comedy of Errors and Shakespeare's last play, The Tempest, are the only two plays that strictly adhere to the classical unities.

- ^ Eric Heinze, "'Were it not against our laws': Oppression and Resistance in Shakespeare's Comedy of Errors", 29 Legal Studies (2009), pp. 230–263

- ^ The identical dates may not be coincidental; the Pauline and Ephesian aspect of the play, noted under Sources, may have had the effect of linking The Comedy of Errors to the holiday season – much like Twelfth Night, another play secular on its surface but linked to the Christmas holidays.

- ^ a b c d e Shakespeare, William (2009). The Comedy of Errors. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-41928-6.

- ^ a b c The Gentleman's Magazine. R. Newton. 1856.

- ^ a b c Ritchie, Fiona; Sabor, Peter (2012). Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-37765-3.

- ^ Galt, John (1886). The Lives of the Players. Hamilton, Adams. p. 309.

oh! it's impossible kemble.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography. 1892.

- ^ Holland, Peter (2014). Garrick, Kemble, Siddons, Kean: Great Shakespeareans. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-6296-0.

- ^ The Comedy of Errors

- ^ "The Comedy of Errors". Court Theatre. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Shakespeare Reviews: The Comedy of Errors". shaltzshakespearereviews.com. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Theatre Is Easy | Reviews | 15 Villainous Fools". www.theasy.com. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "15 Villainous Fools (review)". DC Theatre Scene. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "15 Villainous Fools". Liv & Mags. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Smith, Matt (29 August 2017). "Review: 15 Villainous Fools". Stage Buddy. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ http://www.turntoflesh.org [bare URL]

- ^ "A Comedy of Heirors | New Play Exchange". newplayexchange.org. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Knapp, Zelda (28 December 2017). "A work unfinishing: My Favorite Theater of 2017". A work unfinishing. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Holden, Amanda; Kenyon, Nicholas; Walsh, Stephen, eds. (1993). The Viking Opera Guide. London: Viking. p. 1016. ISBN 0-670-81292-7.

- ^ "Stage history | The Comedy of Errors | Royal Shakespeare Company". www.rsc.org.uk. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 112.

- ^ Neill, Michael; Schalkwyk, David (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Shakespearean Tragedy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-872419-3.

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1962). The Comedy of Errors: Second Series. Cengage Learning EMEA. ISBN 978-0-416-47460-2.

- ^ "Oh, Brother – The Guide to Musical Theatre". guidetomusicaltheatre.com. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Rich, Frank (11 November 1981). "The Stage: 'Oh, Brother!,' a Musical". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "The Bomb-itty of Errors | Samuel French". www.samuelfrench.com. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Budhaditya (2 September 2014). "The Bard in Bollywood". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2 September 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Shakespeare, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 772–797. (See p. 778; section Dramas.)

Editions of The Comedy of Errors

[edit]- Bate, Jonathan and Rasmussen, Eric (eds.), The Comedy of Errors (The RSC Shakespeare; London: Macmillan, 2011)

- Cunningham, Henry (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The Arden Shakespeare, 1st Series; London: Arden, 1907)

- Dolan, Francis E. (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The Pelican Shakespeare, 2nd edition; London, Penguin, 1999)

- Dorsch, T.S. (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The New Cambridge Shakespeare; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988; 2nd edition 2004)

- Dover Wilson, John (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The New Shakespeare; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922; 2nd edition 1962)

- Evans, G. Blakemore (ed.) The Riverside Shakespeare (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974; 2nd edn., 1997)

- Foakes, R.A. (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The Arden Shakespeare, 2nd Series; London: Arden, 1962)

- Greenblatt, Stephen; Cohen, Walter; Howard, Jean E., and Maus, Katharine Eisaman (eds.) The Norton Shakespeare: Based on the Oxford Shakespeare (London: Norton, 1997)

- Jorgensen, Paul A. (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The Pelican Shakespeare; London, Penguin, 1969; revised edition 1972)

- Levin, Harry (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (Signet Classic Shakespeare; New York: Signet, 1965; revised edition, 1989; 2nd revised edition 2002)

- Martin, Randall (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The New Penguin Shakespeare, 2nd edition; London: Penguin, 2005)

- Wells, Stanley (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The New Penguin Shakespeare; London: Penguin, 1972)

- SwipeSpeare The Comedy of Errors (Golgotha Press, Inc., 2011)

- Wells, Stanley; Taylor, Gary; Jowett, John and Montgomery, William (eds.) The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986; 2nd edn., 2005)

- Werstine, Paul and Mowat, Barbara A. (eds.) The Comedy of Errors (Folger Shakespeare Library; Washington: Simon & Schuster, 1996)

- Whitworth, Charles (ed.) The Comedy of Errors (The Oxford Shakespeare: Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002)

Further reading

[edit]- O'Brien, Robert Viking (1996). "The Madness of Syracusan Antipholus". Early Modern Literary Studies. 2 (1): 3.1–26. ISSN 1201-2459.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to The Comedy of Errors at Wikiquote

Quotations related to The Comedy of Errors at Wikiquote Works related to The Comedy of Errors at Wikisource

Works related to The Comedy of Errors at Wikisource Media related to The Comedy of Errors at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Comedy of Errors at Wikimedia Commons- The Comedy of Errors at Standard Ebooks

- The Comedy of Errors at Project Gutenberg

The Comedy of Errors public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Comedy of Errors public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "Modern Translation of the Play" – Modern version of the play

- The Comedie of Errors – HTML version of this title.

- Photos of Gray's Inn Hall – the hall where the play was once performed

- Lesson plans for teaching The Comedy of Errors at Web English Teacher

- Information on the 1987 Broadway production