Dromedary: Difference between revisions

→Diseases and parasites: fleas and ticks |

|||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

The dromedary differs from the ''[[Lama (genus)|Lama]]'' species due to its hump and a shoulder height of above {{convert|170|cm|in|abbr=on}}. It has smaller, round ears, almost square feet and a long, tufted tail. It has four mammary glands while the ''Lama'' species have two, and while dromedaries have three upper premolars ''Lama'' species have two. The [[cranium]] has a well-composed [[sagittal crest]], long facial part and an indented nasal bone.<ref name=mammal>{{cite journal|last=Ilse U. Kohler-Rollefson, edited by Don E. Wilson, Troy L. Best and Alfred L. Gardner|title=Camelus dromedarius|journal=[[Mammalian Species]]|date=12 April 1991|issue=375|pages=1–8|url=http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-375-01-0001.pdf|publisher=The American Society of Mammalogists}}</ref> |

The dromedary differs from the ''[[Lama (genus)|Lama]]'' species due to its hump and a shoulder height of above {{convert|170|cm|in|abbr=on}}. It has smaller, round ears, almost square feet and a long, tufted tail. It has four mammary glands while the ''Lama'' species have two, and while dromedaries have three upper premolars ''Lama'' species have two. The [[cranium]] has a well-composed [[sagittal crest]], long facial part and an indented nasal bone.<ref name=mammal>{{cite journal|last=Ilse U. Kohler-Rollefson, edited by Don E. Wilson, Troy L. Best and Alfred L. Gardner|title=Camelus dromedarius|journal=[[Mammalian Species]]|date=12 April 1991|issue=375|pages=1–8|url=http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-375-01-0001.pdf|publisher=The American Society of Mammalogists}}</ref> |

||

==Diseases and parasites== |

==Diseases and parasites== |

||

Dromedary is prone to [[trypanosomiasis]], a [[parasite|parasitic]] disease caused by ''[[Trypanosoma evansi]]'', ''[[Trypanosoma brucei|T. brucei]]'', ''[[Trypanosoma congolense|T. congolense]]'' and ''[[Trypanosoma simiae|T. simiae]]''. It is transmitted by ''[[Glossina]]''and ''[[Tabinidae]]'' species. The main symptoms are recurring fever, anemia and weakness, which usually ends with the camel's death.<ref name=mammal/> 1039 camels in 33 herds were studied in central Somalia. ''T. evansi'' was a prevalent parasite (1.7%-56.4% in [[blood smear]]s). A total of 2.2% of the camels tested positive for [[brucellosis]] (caused by ''[[Brucella]]'' species.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Baumann|first=M. P. O.|coauthors=Zessin, K. H.|title=Productivity and health of camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Somalia: Associations with trypanosomosis and brucellosis|journal=Tropical Animal Health and Production|date=NaN undefined NaN|volume=24|issue=3|pages=145–156|doi=10.1007/BF02359606}}</ref> Other internal parasites include ''[[Fasciola gigantica]]'' (a [[trematode]]), ''[[Echinococcus polymorphous]]'' and ''[[Taenia marginata]]'' (two [[cestodes]]), ''[[Trichuris]]'', ''[[Nematodirus]]'', ''[[Strongyloides]]'', ''[[Haemonchus]]'' and ''[[Onchocerca]]'' ([[nematodes]]). Among external parasites, ''[[Sarcoptes]]'' species cause [[sarcoptic mange]].<ref name=mammal/> In a study in [[Jordan]], 83% of the 32 camels tested positive for sarcoptic mange, and 33% of the 257 examined specimens were [[Seroprevalence|seroprevalent]] for trypanosomiasis.<ref name=jordan>{{cite journal|last=Odeh F. Al-Rawashdeh|coauthors=Falah K. Al-Ani, Labib A. Sharrif, Khaled M. Al-Qudah, Yasin Al-Hami and Nicholas Frank|title=A survey of camel (Camelus dromedarius) diseases in Jordan|journal=Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine|year=2000|month=September|volume=31|issue=3|pages=335-8|publisher=American Association of Zoo Veterinarians|issn=1042-7260}}</ref> |

Dromedary is prone to [[trypanosomiasis]], a [[parasite|parasitic]] disease caused by ''[[Trypanosoma evansi]]'', ''[[Trypanosoma brucei|T. brucei]]'', ''[[Trypanosoma congolense|T. congolense]]'' and ''[[Trypanosoma simiae|T. simiae]]''. It is transmitted by ''[[Glossina]]''and ''[[Tabinidae]]'' species. The main symptoms are recurring fever, anemia and weakness, which usually ends with the camel's death.<ref name=mammal/> 1039 camels in 33 herds were studied in central Somalia. ''T. evansi'' was a prevalent parasite (1.7%-56.4% in [[blood smear]]s). A total of 2.2% of the camels tested positive for [[brucellosis]] (caused by ''[[Brucella]]'' species.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Baumann|first=M. P. O.|coauthors=Zessin, K. H.|title=Productivity and health of camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Somalia: Associations with trypanosomosis and brucellosis|journal=Tropical Animal Health and Production|date=NaN undefined NaN|volume=24|issue=3|pages=145–156|doi=10.1007/BF02359606}}</ref> Other internal parasites include ''[[Fasciola gigantica]]'' (a [[trematode]]), ''[[Echinococcus polymorphous]]'' and ''[[Taenia marginata]]'' (two [[cestodes]]), ''[[Trichuris]]'', ''[[Nematodirus]]'', ''[[Strongyloides]]'', ''[[Haemonchus]]'' and ''[[Onchocerca]]'' ([[nematodes]]). Among external parasites, ''[[Sarcoptes]]'' species cause [[sarcoptic mange]].<ref name=mammal/> In a study in [[Jordan]], 83% of the 32 camels tested positive for sarcoptic mange, and 33% of the 257 examined specimens were [[Seroprevalence|seroprevalent]] for trypanosomiasis.<ref name=jordan>{{cite journal|last=Odeh F. Al-Rawashdeh|coauthors=Falah K. Al-Ani, Labib A. Sharrif, Khaled M. Al-Qudah, Yasin Al-Hami and Nicholas Frank|title=A survey of camel (Camelus dromedarius) diseases in Jordan|journal=Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine|year=2000|month=September|volume=31|issue=3|pages=335-8|publisher=American Association of Zoo Veterinarians|issn=1042-7260}}</ref> In another study, following the [[rinderpest]] outbreak in [[Ethiopia]], it was found that dromedaries have natural antibodies against [[rinderpest virus]] and [[peste des petits ruminants virus]] (ovine rinderpest).<ref>{{cite journal|last=Roger|first=F.|coauthors=Yesus M. G., Libeau G., Diallo A., Yigezu L. M. and Yilma T.|title=Detection of antibodies of rinderpest and peste des petits ruminants viruses (Paramyxoviridae, Morbillivirus) during a new epizootic disease in Ethiopian camels (Camelus dromedarius)|journal=Revue de Médecine Veterinaire|year=2001|volume=152|issue=3|pages=265-8|publisher=Ecole Nationale Veterinaire De Toulouse|location=France|issn=0035-1555}}</ref> |

||

===Fleas and ticks=== |

|||

The [[flea]] ''[[Vermipsylla alakurt]]'' and [[tick]]s like ''[[Rhipicephalus]]'', ''[[Amblyomma]]'' and ''[[Hyalomma]]'' species cause physical irritations. [[Larva]]e of ''[[Cephalopsis titillator]]'' can cause [[brain compression]], [[nervous disorders]] and even death. Illnesses that can affect dromedary productivity are: pyogenic diseases and wound infections due to ''[[Corynebacterium]]'' and ''[[Streptococcus]]''; pulmonary disorders caused by ''[[Pasteurella]]'' (like [[hemorrhagic septicemia]]) and ''[[Rickettsia]]''; [[camelpox]] due to an oriole virus; [[anthrax]] due to ''[[Bacillus anthracis]]''; and [[Cutaneous innervation|cutaneous skin]] [[necrosis]] due to ''[[Steptothrix]]''species and salt deficiency in diet.<ref name=mammal/> |

|||

In a study in [[Egypt]], 2545 ticks (1491 adults and 1054 nymphs) were collected from dromedaries. The range of the number of ticks per camel was much broad (6 to 173). ''[[Hyalomma dromedarii]]'' was predominant, 95.6% of the adult ticks were this species. Other ticks found were ''H. marginatum'' subspecies and ''H. anatolicum excavatum''. All nymphs were ''Hyalomma'' species. In [[Israel]], the number of ticks per camel ranged from 20 to 105. Here, nine camels in the date palm plantations in Arava valley were injected with [[ivermectin]], but it was not effective against ''Hyalomma'' tick infestations.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Straten|first=M.|coauthors=Jongejan, F.|title=Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting the Arabian Camel (Camelus dromedarius) in the Sinai, Egypt with a note on the acaricidal efficacy of Ivermectin|journal=Experimental and Applied Acarology|date=NaN undefined NaN|volume=17|issue=8|pages=605–616|doi=10.1007/BF00053490}}</ref> |

|||

==Ecology== |

==Ecology== |

||

Revision as of 03:19, 12 August 2012

| Dromedary camel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Camelus dromedarius |

| Binomial name | |

| Camelus dromedarius | |

| |

| Domestic dromedary range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Species synonymy[1]

| |

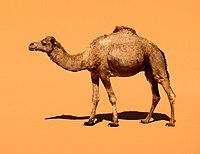

The dromedary camel (pronounced /ˈdrɑmədɛɹi/ or /ˈdrɒmədri/) or Arabian camel (Camelus dromedarius) is a large, even-toed ungulate with one hump on its back. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. The dromedary camel is the second largest member of the camel family after the larger Bactrian camel.

It feeds on foliage, dry grasses and desert vegetation. The camels are active in the day, and rest together in groups. Herds can consist of about 20 individuals. It shows no signs of territoriality, as herds often merge during calamities. They have various adaptations to help them exist in their desert habitat. Mating may occur in winter, but is peak in the rainy season.

Its native range is unclear, but it was in probably the Arabian Peninsula, where it was domesticated about 4000 years ago. The domesticated form occurs widely in North Africa, South Asia and the Middle East.[1] The world's only population of dromedaries exhibiting wild behavior is an introduced feral population in Australia.[2]

Etymology

The scientific name of the dromedary camel is Camelus dromedarius, which could be based on the Greek dromas kamelos, meaning 'running camel'. The Babylonians and Assyrians were the first to refer to the dromedary as gammalu, similar to the word gâmâl used in the Bible.[3]

The term 'dromedary' comes from the Old French word dromedaire, or the Latin word dromedarius, which means 'swift'. It is based on the Greek word dromas, the prefix 'dromad-' meaning runner.[4] An early variant of this word was 'drumblediary' (used in the 1560s).[5] The term 'camel' is derived via Latin and Greek from Hebrew or Phoenician gāmāl, possibly from a verb root meaning 'to bear/carry' (related to Arabic jamala).[6] It may also have an Old French origin from the word chamel and Modern French chameau.[7]

Taxonomy and genetics

The dromedary was first described by Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, in 1758. It is a member of the genus Camelus and the family Camelidae.[1] Earlier the dromedary and camel were considered the same species, but this was corrected by Macedonian philosopher Aristotle of Stagira.[3]

The dromedary camel has 74 chromosomes, as in all other camelids. No karyotypic differences exist among all the camels.[8] The autosomes consist of five pairs of small to medium-sized metacentrics and submetacentrics, in which the X chromosome is the largest. There are 31 pairs of acrocentrics.[9]

Hybrids

The origin of camel hybridization dates back to as early as the 1st millennium BCE.[10] Many hybrids have been known to have been formed with the dromedary. An alpaca crossed with a female dromedary produced a stillborn full-term fetus.[11] In a study, female dromedaries were inseminated with guanaco semen. Two conceived and one female fetus was aborted, while another female fetus was stillborn. Similarly, female guanacos were inseminated with camel semen. Six were conceived, but other than one born prematurely no fetus remained alive. This fetus bore similarities to both a camel and a guanaco.[12]

For about 1000 years Bactrian camel and dromedary have been successfully bred to form hybrids with a long hump slightly indented to a side or a small and a large hump. These hybrids have more strength and size compared to their parents - they can bear more load and are useful.[9][10] A cross between first-generation female hybrid and a male Bactrian camel also produces a useful hybrid. Other types of hybrids are bad-tempered or runts.[9]

History

By the Pleistocene, ancestors of the dromedary came to be known from the Middle East and North Africa.[13] As implied by the Book of Genesis, the dromedary camels were used by nomadic tribes in the second millennium BCE, but the book was composed at a later time, and the theory could not be taken as true.[3] Scholars have dated the spread of dromedaries in the first centuries AD, and evidently before the arrival of the Romans.[14] The Persian invasion of Egypt under Cambyses in 525 BC introduced domesticated camels to the area. The Persian camels, however, were not particularly suited to trading or travel over the Sahara; rare journeys made across the desert were made on chariots pulled by horses.[15]

Stronger and more durable breeds of dromedaries first arrived in Africa in the 4th century. These camels became common after the Islamic conquest of North Africa. While the invasion was accomplished largely on horseback, the new links to the Middle East allowed camels to be imported en masse. These camels were well-suited to long desert journeys and could carry a great deal of cargo, allowing substantial trade over the Sahara for the first time.[16][17] In Libya they were used for transportation within the country and their milk and meat constituted the local diet.[18]

In the mid-seventh century, the dromedary was first used in warfare when Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great made use of these animals while fighting with king Croesus of Lydia in 547 CE. Since then the Persians , Seleucideans, Alexander the Great, Parthians and Sasanians also used dromedaries in warfare. They were also used in the eastern provinces of Egypt, Arabia, Judaea, Syria, Cappadocia, and Mesopotamia.[3]

In 1840, six camels were shipped from Tenerife to Adelaide, but only one survived the trip, arriving on October 12, 1840. Numerous camels were imported into Australia between 1840 and 1907 to open up the arid areas of central and western Australia, which were used mainly for riding and transportation.[19] The explorer John Horrocks was among the first to use camels to explore the arid interior of Australia during the 1840s. About a million feral camels are estimated to live in Australia,[19] descendants of domesticated camels that were released or ran away on their own.

Domestication

Dromedaries were first domesticated in central or southern Arabia. Experts believe it happened around 4000 years ago in the Arabian peninsula.[20][21] It was only in the ninth or tenth millennium BCE when the animal became popular in the Near East. Today there are almost 13 million domesticated dromedaries, found mainly in the area from Western India via Pakistan through Iran to northern Africa. No dromedaries survive in the wild in their original range, although the escaped population of Australian feral camels is estimated to number at least 300,000[22] and possibly over 1 million.[23]

Physical description

The dromedary camel is one of the two largest living camels, alongside the Bactrian camel. Adult male dromedaries grow to a height of 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) and females to 1.7–1.9 m (5.6–6.2 ft). The weight is usually in the range of 400–600 kg (880–1,320 lb) for males, with females being 10% lighter. Large males can weigh as much as 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[24]

Their coats can range from black to a much lighter color, and hair is more on neck, hump and shoulder. Male dromedaries have a soft palate, which they inflate to produce a deep pink sack, which is often mistaken for a tongue, called a doula in Arabic, hanging out of the sides of their mouths to attract females during the mating season. The epidermis is 0.038–0.064 mm (0.0015–0.0025 in) thick, and the dermis is 2.2–4.7 mm (0.087–0.185 in) thick. Though face glands are absent, males have occipital glands 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) below the neck crest, on either side of the midline of the neck. They seem to be modified apocrine sweat glands which secrete a smelly coffee-colored fluid during rut. The mammary glands, four-chambered and cone-shaped, are 2.4 cm (0.94 in) in length and 1.5 cm (0.59 in)in diameter at the base. They can continue to lactate even during dehydration, water content exceeding 90%. The heart is 5 kg (11 lb) in weight, and has two ventricles with the apex curving to left. The spinal cord is an average of 213.6 cm (84.1 in) long, ending at the 2nd and 3rd sacral vertebrae. The kidneys each have a volume of 858 cubic centimeters.[9] The dromedary camel exhibits sexual dimorphism, as both the sexes are much different in their appearances. It is the only mammal that has oval red blood corpuscles and lacks a gall bladder. They have an average lifespan of 40 years,[24] which can be extended to 50 years under captivity.[2]

Dromedaries are also noted for their thick eyelashes. The lenses of their eyes contain crystallin, which constitutes 8-13% of the total protein present there.[25] The dromedary has two toes on each foot, appearing like flat, leathery pads. The hump is of fat bound together by fibrous tissue. Unlike many other animals, camels move both legs on one side of the body at the same time. They show remarkable adaptability in body temperature, from 34°C to 41.7°C,. This is an adaptation to conserve water.[2]

The dromedary differs from the Lama species due to its hump and a shoulder height of above 170 cm (67 in). It has smaller, round ears, almost square feet and a long, tufted tail. It has four mammary glands while the Lama species have two, and while dromedaries have three upper premolars Lama species have two. The cranium has a well-composed sagittal crest, long facial part and an indented nasal bone.[9]

Diseases and parasites

Dromedary is prone to trypanosomiasis, a parasitic disease caused by Trypanosoma evansi, T. brucei, T. congolense and T. simiae. It is transmitted by Glossinaand Tabinidae species. The main symptoms are recurring fever, anemia and weakness, which usually ends with the camel's death.[9] 1039 camels in 33 herds were studied in central Somalia. T. evansi was a prevalent parasite (1.7%-56.4% in blood smears). A total of 2.2% of the camels tested positive for brucellosis (caused by Brucella species.[26] Other internal parasites include Fasciola gigantica (a trematode), Echinococcus polymorphous and Taenia marginata (two cestodes), Trichuris, Nematodirus, Strongyloides, Haemonchus and Onchocerca (nematodes). Among external parasites, Sarcoptes species cause sarcoptic mange.[9] In a study in Jordan, 83% of the 32 camels tested positive for sarcoptic mange, and 33% of the 257 examined specimens were seroprevalent for trypanosomiasis.[27] In another study, following the rinderpest outbreak in Ethiopia, it was found that dromedaries have natural antibodies against rinderpest virus and peste des petits ruminants virus (ovine rinderpest).[28]

Fleas and ticks

The flea Vermipsylla alakurt and ticks like Rhipicephalus, Amblyomma and Hyalomma species cause physical irritations. Larvae of Cephalopsis titillator can cause brain compression, nervous disorders and even death. Illnesses that can affect dromedary productivity are: pyogenic diseases and wound infections due to Corynebacterium and Streptococcus; pulmonary disorders caused by Pasteurella (like hemorrhagic septicemia) and Rickettsia; camelpox due to an oriole virus; anthrax due to Bacillus anthracis; and cutaneous skin necrosis due to Steptothrixspecies and salt deficiency in diet.[9]

In a study in Egypt, 2545 ticks (1491 adults and 1054 nymphs) were collected from dromedaries. The range of the number of ticks per camel was much broad (6 to 173). Hyalomma dromedarii was predominant, 95.6% of the adult ticks were this species. Other ticks found were H. marginatum subspecies and H. anatolicum excavatum. All nymphs were Hyalomma species. In Israel, the number of ticks per camel ranged from 20 to 105. Here, nine camels in the date palm plantations in Arava valley were injected with ivermectin, but it was not effective against Hyalomma tick infestations.[29]

Ecology

In summers, the dromedaries, usually diurnal, rest together in closely packed groups. Generally herds consist of about 20 individuals, led by a dominant male and consisting of several females. Some males either form bachelor groups or roam alone. Pregnant females often separate from the herd and form a herd of other pregnant females.[30] Groups are not territorial, and form herds of over hundreds of animals, joining other herds during natural calamities and when searching for water.[24] During the breeding season males become very aggressive towards each other, sometimes snapping each other and wrestling, while defending the females with them. The male declares his success in the fight with the rival's head between his legs and body. Dromedaries have a reputation for being bad-tempered and obstinate creatures that spit and kick. Free-ranging camels face the large predators typical of their regional distribution, which include wolves, lions, tigers, and humans. Camels are occasionally injured by moving vehicles.[31]

Behavior

Some special behavioral features of the camel include snapping each other without biting, showing displeasure by stamping its feet and running and occasionally vomiting cud when hurt or excited. They prefer walking in a single file. Camels find comfort in scratching parts of their body with their front or hind legs or with their lower incisors. They are also seen rubbing against tree bark and rolling in the sand. The main vocalizations include a sheep-like bleat used to locate individuals and the breeding gurgle of males, while a whistling noise is produced as a threat noise by males by grinding the teeth together.[2] Dromedaries interact with their food source by taking small bites of each plant and thus not killing the plant.

In a study it was found that androgen levels in the blood of males controlled their behavior. In between January to April, when these levels went high, they became quite unmanageable, blew-out a palatal flap from the mouth, vocalized, and threw urine over their backs with their tails.[32]

Diet

The diet of the camel mostly consists of foliage, dry grasses and available desert vegetation. Mostly thorny plants occur in its natural habitat.[33] Its highly preferred species include the quandong (Santalum acuminatum), plumbush (S. lanceolatum), curly pod wattle (Acacia sessiliceps), native apricot(Pittosporum angustifolium), bean tree (Erythrina vespertilio), and Lawrencia species.[19] They keep their mouth open while chewing thorny food. They use their lips to grasp the food, then chew each bite 40-50 times. Features like long eyelashes, eyebrows, lockable nostrils, caudal opening of the prepuce and a relatively small vulva avoid injuries, especially while feeding.[33]

A study on the diet of the dromedary, done in eastern Ethiopia, showed that the camels spent most time in the day grazing. The young camels generally grazed for more time than adults. The adults did not graze much and mainly rested or did other activities in the wet season. Overall, grazing was most in the dry season while other activities prevailed in the wet season. Observations of their foraging behavior showed that Opuntia plants were the most-eaten plants in the dry season as Acacia brevispica in the wet season.[34]

Adaptations

Dromedary camels have several adaptations for their desert habitat. A double row of eyelashes and the unique ability of closing their nostrils enables the camels to prevent the sand and dust from entering, even in a sandstorm. Dromedaries can conserve water by fluctuating their body temperature throughout the day from 34–41.7 °C (93.2–107.1 °F), which saves water by avoiding perspiration at the rise of the external temperature.[24] The kidneys are specialized so that not much water is excreted.[35] Groups of camels also avoid excess heat from the environment by pressing against each other. Dromedary camels can tolerate greater than 30% water loss, which is almost impossible for most of other mammals. Water is expended primarily from interstitial and intracellular bodily fluids. They have the unique capability of drinking 100 L of water in just 10 minutes.[2] A very thirsty animal can drink up even 30 gallons (135 liters) of water in only 13 minutes[36] and a dehydrated camel 200 liters in just three minutes.

The hump stores up to 80 pounds (36 kilograms) of fat, which a camel can break down into water and energy when sustenance is not available. If the hump is small, the animal can show starvation. The hair is longer at the throat, hump and shoulders. The pads widen under the weight of the dromedary when it steps on the ground.[2][36] This prevents the dromedary from sinking much into the sand. When the dromedary walks, it moves both the feet on the same side of the body simultaneously, then the same movement is repeated on the other side of the body. This way of walking makes the body swing from side to side as the dromedary walks ahead, hence the nickname of the animal; "the ship of the desert".[24] The thick lips help in eating coarse and thorny plants.

Reproduction

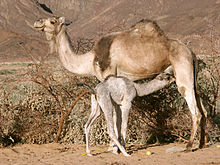

Females reach sexual maturity around 3 years of age and mate around age 4 or 5. Males begin to mate at around 3 years of age, too, but still are not sexually mature until six years of age. Breeding occurs in winters but is peak in the rainy season. The onset of the breeding season is believed to be cued by nutritional status of the camel and the daylength.

If mating does not occur, the follicle, which grow during estrus, usually regress within a few days.[37] In a study 35 complete estrus cycles were observed in five non-pregnant females over a period of 15 months. The cycles were about 28 days long, in which follicles matured in six days, maintained their size for 13 days and returned to their original size in eight days.[38] In another study it was found that ovulation could be best induced when the follicle reaches a size of 0.9–1.9 cm (0.35–0.75 in).[39]

During the reproductive season, males splash their urine on their tails and nearer regions. Males also extrude their soft palate. Copious saliva turns to foam as the male gurgles, covering the mouth.[2] Males threaten each other for dominance over the female by trying to stand taller than the other, making low noises and a series of head movements including lowering, lifting, and bending their necks backwards, A male tries to defeat other males by biting at his legs and taking the opponent's head in between his jaws. Copulation time ranges from 7–35 minutes, averaging 11–15 minutes. A single calf is born after a gestational period of 15 months. Calves move freely by the end of their first day. Nursing and maternal care continues for 1–2 years.[2]

Habitat and distribution

The dromedary camel occupies arid regions, notably the Sahara desert in Africa. The original range of the camel’s wild ancestors was probably south Asia and the Arabian peninsula. Commonly found in African, Arabian, Indian and Middle Eastern deserts, the dromedary camel is also found in feral populations in Australia.[24]

Uses

Dromedaries are used as beasts of burden in most of their domesticated range. Unlike horses, they kneel for the loading of passengers and cargo.

Their hair is also used as a source material for woven goods, ranging from Bedouin tents to garments. They also have significant culinary uses. Dromedary meat is widely consumed in the Arabian Peninsula, Somalia, Sudan, and, to a lesser extent, Egypt, among other places. Dromedary milk is also consumed by people.[40] Border guards in many remote desert locations in Egypt use camels for patrols. Such mounted border guards are called هجان haggan (pl. هجانة hagganah).

Dairy products

Camel milk is a staple food of desert nomad tribes, and is richer in fat and protein than cow milk. It is said[weasel words] to have many health-conserving[vague] properties[citation needed]. It is used as a medicinal product in India[citation needed] and as an aphrodisiac in Ethiopia. Bedouins believe the curative powers of camel milk are enhanced if the camel's diet consists of certain plants. The milk can readily be made into yogurt, but is difficult to make into butter or cheese. Butter or yogurt made from camel milk can have a faint greenish tinge.

Camel milk cannot be made into butter by the traditional churning method. It can be made if it is soured first, churned, and a clarifying agent added, or if it is churned at 24–25 °C (75–77 °F), but times vary greatly in achieving results. Until recently, camel milk could not be made into cheese because rennet was unable to coagulate the milk proteins to allow the collection of curds. Under the commission of the FAO, Professor J.P. Ramet of the École Nationale Supérieure d'Agronomie et des Industries Alimentaires was able to produce curdling by the addition of calcium phosphate and vegetable rennet.[41] The cheese produced from this process has low levels of cholesterol and lactose, but sales are limited owing to the low yield of cheese from milk and the uncertainty of pasteurization levels for camel milk, which makes adherence to dairy import regulations difficult.

Meat

A camel carcass can provide a substantial amount of meat. The male dromedary carcass can weigh 400 kg (882 lb) or more. The carcass of a female camel weighs less than that of the male, ranging between 250 and 350 kg (550 and 770 lb). The brisket, ribs and loin are among the preferred parts, but the hump is considered a delicacy and is most favored.[citation needed] It is reported[by whom?] that camel meat tastes like coarse beef, but older camels can prove to be very tough and less flavorful.

Camel meat is low in fat, and can thus taste dry. The Abu Dhabi Officers' Club serves a camel burger, as this allows the meat to be mixed with beef or lamb fat, improving both the texture and taste. In Karachi, Pakistan, the exclusive Nihari restaurants prepare this dish from camel meat, while the general restaurants prepare it with either beef or meat from the water buffalo.

Camel meat has been eaten for centuries. It has been recorded by ancient Greek writers as an available dish in ancient Persia at banquets, usually roasted whole. The ancient Roman emperor Heliogabalus enjoyed camel's heel. Camel meat is still eaten in certain regions, including Somalia, where it is called hilib geel, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Libya, Sudan, Kazakhstan and other arid regions where alternative forms of protein may be limited or where camel meat has had a long cultural history.

In the Middle East, camel meat is the rarest and most prized source of pastırma.[citation needed] In addition to the meat, the blood can also be consumed. In northern Kenya camel blood is an important source of iron, vitamin D, salts and minerals. Camel meat is also occasionally found in Australian cuisine, including a camel lasagne served in Alice Springs restaurants.

Health issues

A 2005 report, issued jointly by the Saudi Ministry of Health and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, details cases of human bubonic plague resulting from the ingestion of raw camel liver.[42]

Cultural prohibitions on consuming camel products

According to Jewish tradition, camel meat and milk are not kosher. Camels possess only one of the two kosher criteria; although they chew their cuds, they do not possess cloven hooves. (See: Taboo food and drink)

See also

- Camel

- Bactrian camel

- Camel racing

- Camel troops

- Camel wrestling

- Camelops

- Australian feral camel

- Camel farming in Sudan

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 646. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Naumann, Robert. "Camelus dromedarius". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d Lendering, Jona (2004). "Camels and dromedaries". Livius.org. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Dromedary". Oxford University Press. Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Dromedary". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, entry camel (noun)

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Camel". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ E. Mukasa-Mugerwa (1981). The Camel (Camelus Dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review. Ethiopia: International Livestock Centre for Africa.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ilse U. Kohler-Rollefson, edited by Don E. Wilson, Troy L. Best and Alfred L. Gardner (12 April 1991). "Camelus dromedarius" (PDF). Mammalian Species (375). The American Society of Mammalogists: 1–8.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Potts, D. T. (1 June 2004). "Camel Hybridization and the Role of Camelus Bactrianus in the Ancient Near East". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 47 (2): 143–165. doi:10.1163/1568520041262314.

- ^ Fowler, Murray E. (2011). Medicine and Surgery of Camelids. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Skidmore, J. A. (7 April 1999). "Hybridizing Old and New World camelids: Camelus dromedarius x Lama guanicoe". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1420): 649–656. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0685.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Prothero, Donald R. (2002). Horns, tusks, and flippers : the evolution of hoofed mammals. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-8018-7135-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gellner, Anatoly M. Khazanov ; translated by Julia Crookenden ; with a foreword by Ernest (1994). Nomads and the outside world (2nd ed. ed.). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-299-14284-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Edited by Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1979). The International standard Bible encyclopedia, Volume one: A-D (Fully rev. ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-3781-6.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Harris, Nathaniel (2003). Atlas of the World's Deserts. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 223. ISBN 0-203-49166-1.

- ^ Kaegi, Walter E. (2010). Muslim expansion and Byzantine collapse in North Africa (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- ^ Ed. by Richard I. Lawless and Allan M. Findlay (1984). North Africa : contemporary politics and economic development (1. publ. ed.). London: Croom Helm. p. 128. ISBN 0-7099-1609-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Camel fact sheet". Australian Government. Department of Sustainability, Environment, water, Population and Communities.

- ^ Edited by Paul Pierre Pastoret (1998). Handbook of vertebrate immunology. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-546401-0.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Peters, J (1997 November). "[The dromedary: ancestry, history of domestication and medical treatment in early historic times]". Tierarztliche Praxis. Ausgabe G, Grosstiere/Nutztiere. 25 (6): 559–65. PMID 9451759.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Farmnote 122/2000 : Feral camel [Western Australia]" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ Northern Territory Government. "Feral Camel - Camelus dromedarius". Natural Resources, Environment, The Arts and Sport. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Huffman, Brent. "Dromedary, Arabian camel". Ultimate Ungulate.

- ^ Garland, Donita (15 February 1991). "ζ-Crystallin is a major protein in the lens of Camelus dromedarius". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 285 (1): 134–136. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(91)90339-K.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Baumann, M. P. O. (NaN undefined NaN). "Productivity and health of camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Somalia: Associations with trypanosomosis and brucellosis". Tropical Animal Health and Production. 24 (3): 145–156. doi:10.1007/BF02359606.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Odeh F. Al-Rawashdeh (2000). "A survey of camel (Camelus dromedarius) diseases in Jordan". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 31 (3). American Association of Zoo Veterinarians: 335–8. ISSN 1042-7260.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Roger, F. (2001). "Detection of antibodies of rinderpest and peste des petits ruminants viruses (Paramyxoviridae, Morbillivirus) during a new epizootic disease in Ethiopian camels (Camelus dromedarius)". Revue de Médecine Veterinaire. 152 (3). France: Ecole Nationale Veterinaire De Toulouse: 265–8. ISSN 0035-1555.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Straten, M. (NaN undefined NaN). "Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting the Arabian Camel (Camelus dromedarius) in the Sinai, Egypt with a note on the acaricidal efficacy of Ivermectin". Experimental and Applied Acarology. 17 (8): 605–616. doi:10.1007/BF00053490.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McBabe, James. "Life Cycle". BioWeb.

- ^ Gauthier-Pilters, Hilde. 1981. The camel, its evolution, ecology, behavior, and relationship to man. Chicago :University of Chicago Press. 208 p.

- ^ Yagil, R. (1 January 1980). "Hormonal and behavioural patterns in the male camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Reproduction. 58 (1): 61–65. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0580061. PMID 7359491.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sambraus, HH (1994 Jun). "Biological function of morphologic peculiarities of the dromedary". Tierarztliche Praxis. 22 (3): 291–3. PMID 8048041.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dereje, Moges (24 June 2005). "The browsing dromedary camel". Animal Feed Science and Technology. 121 (3–4): 297–308. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2005.01.017.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramet, J.-P. (2001). The technology of making cheese from camel milk (Camelus dromedarius). Rome: FAO. ISBN 92-5-103154-1.

- ^ a b "Arabian (Dromedary) Camel (Camelus dromedarius)". National Geographic.

- ^ Skidmore, J. A. "Reproduction in dromedary camels: an update" (PDF). Animal Reproduction. 2 (3): 161–171.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Musa, B. (16 December 1978). "The oestrous cycle of the camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Veterinary Record. 103 (25): 556–557. doi:10.1136/vr.103.25.556.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Skidmore, J. A. (1 March 1996). "The ovarian follicular wave pattern and induction of ovulation in the mated and non-mated one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius)". Reproduction. 106 (2): 185–192. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.1060185. PMID 8699400.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The Seventy Great Inventions of the Ancient World by Brian M. Fagan

- ^ Fresh from your local drome'dairy'? Food and Agriculture Organization, July 6, 2001

- ^ Bin Saeed AA, Al-Hamdan NA, Fontaine RE (2005). "Plague from eating raw camel liver". Emerging Infect Dis. 11 (9): 1456–7. PMC 3310619. PMID 16229781.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. In some contexts, dromedary, which derives from the Greek δραμεῖν (to run), can refer to any swift riding camel, regardless of the number of humps it has.

- M. M. Sophie Smuts, A. J. Bezuidenhout (1987). Anatomy of the dromedary. Clarendon Press.

External links

Media related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikispecies

Data related to Camelus dromedarius at Wikispecies The dictionary definition of dromedary at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of dromedary at Wiktionary