Minocycline: Difference between revisions

→Indications: moving |

|||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

*'''Minoz''' (In Romania) |

*'''Minoz''' (In Romania) |

||

StoneBridge Pharma also markets Minocycline as '''Cleeravue-M''' in combination with SteriLid eyelid cleanser in the treatment of [[rosacea]] [[blepharitis]]. |

StoneBridge Pharma also markets Minocycline as '''Cleeravue-M''' in combination with SteriLid eyelid cleanser in the treatment of [[rosacea]] [[blepharitis]]. |

||

==Research== |

|||

Early research has found a tentative benefit from minocycline in [[schizophrenia]].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Dean|first=OM|coauthors=Data-Franco, J; Giorlando, F; Berk, M|title=Minocycline: therapeutic potential in psychiatry.|journal=CNS drugs|date=2012 May 1|volume=26|issue=5|pages=391-401|pmid=22486246}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 08:10, 14 September 2013

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Minocin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682101 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Elimination half-life | 11–22 hours |

| Excretion | mostly fecal, rest renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.226.626 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

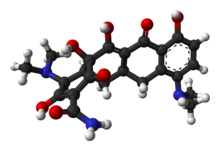

| Formula | C23H27N3O7 |

| Molar mass | 457.477 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Minocycline (INN) is a broad-spectrum tetracycline antibiotic, and has a broader spectrum than the other members of the group. It is a bacteriostatic antibiotic, classified as a long-acting type. As a result of its long half-life it generally has serum levels 2–4 times that of the simple water-soluble tetracyclines (150 mg giving 16 times the activity levels compared with 250 mg of tetracycline at 24–48 hours).

Minocycline is the most lipid-soluble of the tetracycline-class antibiotics, giving it the greatest penetration into the prostate and brain, but also the greatest amount of central nervous system (CNS)-related side effects, such as vertigo. A common side effect is diarrhea. Uncommon side effects (with prolonged therapy) include skin discolouration and autoimmune disorders that are not seen with other drugs in the class.

Minocycline is a relatively poor tetracycline-class antibiotic choice for urinary pathogens sensitive to this antibiotic class, as its solubility in water and levels in the urine are less than all other tetracyclines. Minocycline is metabolized by the liver and has poor urinary excretion.

Minocycline is not a naturally-occurring antibiotic, but was synthesized semi-synthetically from natural tetracycline antibiotics by Lederle Laboratories in 1972, and marketed by them under the brand name Minocin.[2]

Medical uses

Minocycline and doxycycline are frequently used for the treatment of acne vulgaris.[3][4] Both of these closely related antibiotics have similar levels of efficacy, although doxycycline has a slightly lower risk of adverse side effects.[5] Historically, minocycline has been a very effective treatment for acne vulgaris.[6] However, acne that is caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria is a growing problem in many countries.[7] In Europe and North America, a significant number of acne patients no longer respond well to treatment with tetracycline family antibiotics (e.g. tetracycline, doxycycline and minocycline) because their acne symptoms are caused by bacteria (primarily Propionibacterium acnes) that are resistant to these antibiotics.[8]

Minocycline is also used for other skin infections such as MRSA[9] as well as Lyme disease,[10] as the one pill twice daily 100 mg dosage is far easier for patients than the four times a day required with tetracycline or oxytetracycline. Its activity against Lyme disease is enhanced by its superior ability to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Although minocycline's broader spectrum of activity, compared with other members of the group, includes activity against Neisseria meningitidis,[11] its use as a prophylaxis is no longer recommended because of side effects (dizziness and vertigo).

It may be used to treat certain strains of MRSA infection and a disease caused by drug resistant acinetobacter.[12]

Both minocycline and doxycycline have shown effectiveness in asthma due to immune suppressing effects.[13] Minocycline as well as doxycycline have modest effectiveness in treating rheumatoid arthritis.[14] It is recognized as a DMARDS (Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug) by the American College of Rheumatology, which recommends its use as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis.[citation needed]

A list of indications for which minocycline has been used include;

- Amoebic dysentery

- Anthrax

- Cholera

- Gonorrhea (when penicillin cannot be given)

- Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome (confluent and reticulated papillomatosis)

- Bubonic plague

- Perioral dermatitis[15]

- Periodontal disease

- Respiratory infections such as pneumonia

- HIV—for use as an adjuvant to HAART[16]

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

- Rosacea

- Syphilis (when penicillin cannot be given)

- Urinary tract infections, rectal infections, and infections of the cervix caused by certain microbes

- Hidradenitis suppurativa

Cautions

Contrary to most other tetracycline antibiotics (doxycycline excluded), minocycline may be used in renal impairment, but may aggravate systemic lupus erythematosus.[17] It may also trigger or unmask autoimmune hepatitis.[18]

Also, more so than other tetracyclines, minocycline can cause the rare condition of secondary intracranial hypertension which has initial symptoms of headache, visual disturbances, dizziness, vomiting, and confusion.[citation needed] Cerebral edema, as well as autoimmune rheumatoid arthritis are rare side effects to minocycline in some people.[19]

Minocycline, like most tetracyclines, becomes dangerous past its expiration date.[20] While most prescription drugs lose potency after their expiration dates, tetracyclines are known to become toxic over time. Expired tetracyclines can cause serious damage to the kidney due to the formation of a degradation product, anhydro-4-epitetracycline.[20] Minocycline's absorption is impaired if taken at the same time of day as calcium or iron supplements. Unlike some of the other tetracycline group antibiotics, it can be taken with calcium-rich foods such as milk, although this does reduce the absorption slightly.[21] Minocycline should be taken with plenty of water.[citation needed] If taking this drug, one should avoid prolonged or excessive exposure to direct sunlight.[citation needed]

A study published in 2007, suggested that minocycline harms ALS patients. Patients on minocycline declined more rapidly than those on placebo. The mechanism of this side effect is unknown, although a hypothesis is that the drug exacerbated an autoimmune component of the primary disease. According to the researcher from Columbia University the effect does not seem to be dose-dependent because the patients on high doses did not do worse than those on the low doses.[22]

Side effects

Minocycline may cause upset stomach, diarrhea, dizziness, unsteadiness, drowsiness, mouth sores, headache and vomiting. Minocycline increases sensitivity to sunlight. Minocycline may effect quality of sleep and rarely cause sleep disorders.[23] It has also been linked to cases of lupus. Minocycline can reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives.[24] Prolonged use of minocycline over an extended period of time can lead to blue-gray skin and blue-gray staining of scar tissue is not permanent but it can take a very long time for the skin colour to return to normal; on the other hand a muddy brown skin colour in sun exposed areas is usually a permanent skin discolouration.[25] Permanent blue discoloration of gums or teeth discoloration may also occur. Rare but serious side effects include fever, yellowing of the eyes or skin, stomach pain, sore throat, vision changes, and mental changes, including depersonalization.[26][27]

Occasionally minocycline therapy may result in autoimmune disorders such as drug related lupus and auto-immune hepatitis; minocycline induced auto-immune hepatitis when it occurs usually occurs in men who also developed minocycline induced lupus, however, women are the most likely to develop minocycline induced lupus. Significant or complete recovery occurs in most people who develop minocycline induced autoimmune problems within a period of a couple of weeks to a year of cessation of minocycline therapy. Autoimmune problems emerge during chronic therapy but can sometimes occur after only short courses of a couple of weeks of therapy.[28][29] Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome can occur during the first few weeks of therapy with minocycline.[29]

Minocycline, but not other tetracyclines, can cause vestibular disturbances with dizziness, ataxia, vertigo and tinnitus. These effects are again thought to be related to minocycline's greater penetration into the central nervous system. Vestibular side effects are much more common in women than in men, occurring in 50% to 70% of women receiving minocycline. As a result of the frequency of this bothersome side effect, minocycline is rarely used in female patients.[30]

Symptoms of an allergic reaction include rash, itching, swelling, severe dizziness, and trouble breathing.[26] Minocycline has also been reported to very rarely cause idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri),[31] a side effect also more common in female patients.

Thyroid cancer has been reported in the post-marketing setting in association with minocycline products. When minocycline therapy is given over prolonged periods, monitoring for signs of thyroid cancer should be considered.[citation needed]

In 2009, the FDA added minocycline to its Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS); a list of medications under investigation by the FDA for potential safety issues. The AERS cites a potential link between the use of minocycline products and autoimmune disease in pediatric patients.[32]

Anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective

In various models of neurodegenerative disease, minocycline has demonstrated neurorestorative as well as neuroprotective properties. Neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington's disease and Parkinson's disease have shown a particularly beneficial response to minocycline in research studies, and an antipsychotic benefit has been found in people with schizophrenia and minocycline is proposed as a possible addon therapy for some schizophrenics.[33][34][35] Current research is examining the possible neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of minocycline against progression of a group of neurodegenerative disorders including multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Huntington's disease, and Parkinson's disease.[36][37][38][39] As mentioned above, minocycline harms ALS patients.

In the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Chris Zink, Janice Clements, and colleagues from Johns Hopkins University reported that minocycline may exhibit neuroprotective action against AIDS Dementia Complex by inhibiting macrophage inflammation and HIV replication in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid.[40] Minocycline may suppress viral replication by reducing T cell activation.[41][42] The neuroprotective action of minocycline may include its inhibitory effect on 5-lipoxygenase,[43] an inflammatory enzyme associated with brain aging, and the antibiotic is being studied for use in Alzheimer's disease patients.[44] Minocycline may also exert neuroprotective effects independent of its anti-inflammatory properties.[45] Minocycline also has been used as a "last-ditch" treatment for toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients.[citation needed] Minocycline is somewhat neuroprotective in mouse models of Huntington's disease.[46]

As an anti-inflammatory, minocycline inhibits apoptosis (cell death) via attenuation of TNF-alpha, downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokine output. This effect is mediated by a direct action of minocycline on the activated T cells and on microglia, which results in the decreased ability of T cells to contact microglia which impairs cytokine production in T cell-microglia signal transduction .[47] Minocycline also inhibits microglial activation, through blockade of NF-kappa B nuclear translocation.[citation needed]

A 2007 study reported the impact of the antibiotic minocycline on clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) outcomes and serum immune molecules in 40 MS patients over 24 months of open-label minocycline treatment. Despite a moderately high pretreatment relapse rate in the patient group prior to treatment (1.3/year pre-enrollment; 1.2/year during a three-month baseline period), no relapses occurred between months 6 and 24 on minocycline. Also, despite significant MRI disease-activity pretreatment (19/40 scans had gadolinium-enhancing activity during a three-month run-in), the only patient with gadolinium-enhancing lesions on MRI at 12 and 24 months was on half-dose minocycline. Levels of interleukin-12 (IL-12), which at high levels might antagonize the proinflammatory IL-12 receptor, were elevated over 18 months of treatment, as were levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). The activity of matrix metalloproteinase-9 was decreased by treatment. Clinical and MRI outcomes in this study were supported by systemic immunological changes and call for further investigation of minocycline in MS.[48][49][45][50]

A recent study (2007) found that patients taking 200 mg of minocycline for five days within 24 hours of an ischemic stroke showed an improvement in functional state and stroke severity over a period of three months compared with patients receiving placebo.[51]

Trade names and availability

Minocycline is no longer covered by patent and is therefore marketed under several trade names:

- Minomycin

- Akamin

- Minocin

- Minoderm

- Cyclimycin

- Arestin (1 mg doses administered locally into periodontal pockets, after scaling and root planing, for treatment of periodontal disease.)[52]

- Aknemin

- Solodyn (Extended-Release. For the treatment of acne)

- Dynacin

- Sebomin

- Mino-Tabs

- Acnamino

- Minopen (In Japan)

- Maracyn 2 (For treatment of bacterial infections in aquarium fish and amphibians)

- Quatrocin (In Syria)

- Minox (In Ireland)

- Minoz (In Romania)

StoneBridge Pharma also markets Minocycline as Cleeravue-M in combination with SteriLid eyelid cleanser in the treatment of rosacea blepharitis.

Research

Early research has found a tentative benefit from minocycline in schizophrenia.[53]

References

- ^ DrugBank: DB01017 (Minocycline)

- ^ "The Tetracyclines". Lin, DW. March 2005.

- ^ Strauss; et al. (2007). "Guidelines of care for acne vulgaris management". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 56 (4): 651–63. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.048. PMID 17276540.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ^ "Minocycline, Doxycycline and Acne Vulgaris". ScienceOfAcne.com. 07/11/2011. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kircik LH (2010). "Doxycycline and minocycline for the management of acne: a review of efficacy and safety with emphasis on clinical implications". J Drugs Dermatol. 9 (11): 1407–11. PMID 21061764.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hubbell; et al. (1982). "Efficacy of minocycline compared with tetracycline in treatment of acne vulgaris". Archives of Dermatology. 118 (12): 989–92. PMID 6216858.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ^ Eady; et al. (2003). "Propionibacterium acnes resistance: a worldwide problem". Dermatology. 206 (1): 54–6. PMID 12566805.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ^ Ross; et al. (2003). "Antibiotic-resistant acne: lessons from Europe". British Journal of Dermatology. 148 (3): 467–78. PMID 12653738.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help) - ^ Rogers RL, Perkins J (2006). "Skin and soft tissue infections". Prim. Care. 33 (3): 697–710. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2006.06.005. PMID 17088156.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bernier C, Dréno B (2001). "[Minocycline]". Ann Dermatol Venereol (in French). 128 (5): 627–37. PMID 11427798.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fraser A, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Leibovici L (2005). "Prophylactic use of antibiotics for prevention of meningococcal infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials". Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24 (3): 172–81. doi:10.1007/s10096-005-1297-7. PMID 15782277.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bishburg E, Bishburg K (2009). "Minocycline--an old drug for a new century: emphasis on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Acinetobacter baumannii". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 34 (5): 395–401. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.021. PMID 19665876.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Joks R, Durkin HG (2011). "Non-antibiotic properties of tetracyclines as anti-allergy and asthma drugs". Pharmacol. Res. 64 (6): 602–9. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2011.04.001. PMID 21501686.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Greenwald RA (2011). "The road forward: the scientific basis for tetracycline treatment of arthritic disorders". Pharmacol. Res. 64 (6): 610–3. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2011.06.010. PMID 21723947.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ U.S. National Library of Medicine (2009, Dec 11) 'Perioral dermatitis'. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Copeland KF, Brooks JI. (15 April 2010). "A Novel Use for an Old Drug: The Potential for Minocycline as Anti-HIV Adjuvant Therapy" (PDF). J Infect Dis. 201 (8): 1115–7. doi:10.1086/651278. PMID 20205572.

- ^ Gough A, Chapman S, Wagstaff K, Emery P, Elias E (1996). "Minocycline induced autoimmune hepatitis and systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome". BMJ. 312 (7024): 169–72. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7024.169. PMC 2349841. PMID 8563540.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krawitt EL (2006). "Autoimmune hepatitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (1): 54–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMra050408. PMID 16394302.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lefebvre N; Forestier E; Farhi D; et al. (2007). "Minocycline-induced hypersensitivity syndrome presenting with meningitis and brain edema: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 1: 22. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-1-22. PMC 1884162. PMID 17511865.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "Principles and methods for the assessment of nephrotoxicity associated with exposure to chemicals". Environmental health criteria: 119. World Health Organization (WHO). ISBN 92-4-157119-5. ISSN 0250-863X. 1991

- ^ Piscitelli, Stephen C. (2005). Drug Interactions in Infectious Diseases. Humana Press. ISBN 1-58829-455-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Science Vol 318, 1227, 2007

- ^ Nonaka K, Nakazawa Y, Kotorii T (1983). "Effects of antibiotics, minocycline and ampicillin, on human sleep". Brain Res. 288 (1–2): 253–9. PMID 6661620.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "MedlinePlus Drug Information: Minocycline Oral".

- ^ Geria AN, Tajirian AL, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA (2009). "Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update". Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 17 (2): 123–6. PMID 19595269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b MedicineNet: Minocycline Oral (Dynacin, Minocin) - side effects, medical uses, and drug interactions

- ^ Cohen, P. R. (2004). "Medication-associated depersonalization symptoms: report of transient depersonalization symptoms induced by minocycline". Southern Medical Journal. 97 (1): 70–73. doi:10.1097/01.SMJ.0000083857.98870.98. PMID 14746427.

- ^ Mongey AB, Hess EV (2008). "Drug insight: autoimmune effects of medications-what's new?" (PDF). Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 4 (3): 136–44. doi:10.1038/ncprheum0708. PMID 18200008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ochsendorf F (2010). "Minocycline in acne vulgaris: benefits and risks". Am J Clin Dermatol. 11 (5): 327–41. doi:10.2165/11319280-000000000-00000. PMID 20642295.

- ^ Sweet, Richard L. (2001). Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 635.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Friedman DI (2005). "Medication-induced intracranial hypertension in dermatology". Am J Clin Dermatol. 6 (1): 29–37. PMID 15675888.

- ^ FDA Adverse Events Reporting System Retrieved on January 16, 2011

- ^ Miyaoka T (2008). "Clinical potential of minocycline for schizophrenia". CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 7 (4): 376–81. doi:10.2174/187152708786441858. PMID 18991666.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04666yel, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.4088/JCP.08m04666yelinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1177/0269881112444941, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1177/0269881112444941instead. - ^ "Preliminary Study Shows Creatine and Minocycline May Warrant Further Study In Parkinson's Disease" (Press release). National Institute of Health. February 23, 2006.

- ^ Chen M, Ona VO, Li M, Ferrante RJ, Fink KB, Zhu S, Bian J, Guo L, Farrell LA, Hersch SM, Hobbs W, Vonsattel JP, Cha JH, Friedlander RM (2000). "Minocycline inhibits caspase-1 and caspase-3 expression and delays mortality in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington disease". Nat Med. 6 (7): 797–801. doi:10.1038/77528. PMID 10888929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tikka TM, Koistinaho JE (15 June 2001). "Minocycline provides neuroprotection against N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotoxicity by inhibiting microglia" (PDF). J Immunol. 166 (12): 7527–33. PMID 11390507.

- ^ Nirmalananthan N, Greensmith L (2005). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: recent advances and future therapies". Curr. Opin. Neurol. 18 (6): 712–9. doi:10.1097/01.wco.0000187248.21103.c5. PMID 16280684.

- ^ Zink MC, Uhrlaub J, DeWitt J, Voelker T, Bullock B, Mankowski J, Tarwater P, Clements J, Barber S (2005). "Neuroprotective and anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of minocycline". JAMA. 293 (16): 2003–11. doi:10.1001/jama.293.16.2003. PMID 15855434.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20205570, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20205570instead. - ^ Szeto, G; Brice, A; Yang, H; Barber, S; Siliciano, R; Clements, J (2010). "Minocycline attenuates HIV infection and reactivation by suppressing cellular activation in human CD4+ T cells". The Journal of infectious diseases. 201 (8): 1132–40. doi:10.1086/651277. PMID 20205570.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Song Y, Wei EQ, Zhang WP, Zhang L, Liu JR, Chen Z (2004). "Minocycline protects PC12 cells from ischemic-like injury and inhibits 5-lipoxygenase activation". NeuroReport. 15 (14): 2181–4. doi:10.1097/00001756-200410050-00007. PMID 15371729.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Uz T, Pesold C, Longone P, Manev H (1 April 1998). "Aging-associated up-regulation of neuronal 5-lipoxygenase expression: putative role in neuronal vulnerability" (PDF). FASEB J. 12 (6): 439–49. PMID 9535216.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maier K, Merkler D, Gerber J, Taheri N, Kuhnert AV, Williams SK, Neusch C, Bähr M, Diem R (2007). "Multiple neuroprotective mechanisms of minocycline in autoimmune CNS inflammation". Neurobiol. Dis. 25 (3): 514–25. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.022. PMID 17239606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Beal F, Ferrante J (2004). "Experimental Therapeutics in Transgenic Mouse Models of Huntington's Disease". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 5: 373–84. doi:10.1038/nrnl1386.

- ^ Giuliani F, Hader W, Yong VW (2005). "Minocycline attenuates T cell and microglia activity to impair cytokine production in T cell-microglia interaction". J. Leukoc. Biol. 78 (1): 135–43. doi:10.1189/jlb.0804477. PMID 15817702.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zabad RK, Metz LM, Todoruk TR, Zhang Y, Mitchell JR, Yeung M, Patry DG, Bell RB, Yong VW (2007). "The clinical response to minocycline in multiple sclerosis is accompanied by beneficial immune changes: a pilot study". Mult. Scler. 13 (4): 517–26. doi:10.1177/1352458506070319. PMID 17463074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zemke D, Majid A (2004). "The potential of minocycline for neuroprotection in human neurologic disease". Clinical neuropharmacology. 27 (6): 293–8. doi:10.1097/01.wnf.0000150867.98887.3e. PMID 15613934.

- ^ Popovic N, Schubart A, Goetz BD, Zhang SC, Linington C, Duncan ID (2002). "Inhibition of autoimmune encephalomyelitis by a tetracycline". Ann. Neurol. 51 (2): 215–23. doi:10.1002/ana.10092. PMID 11835378.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lampl Y; Boaz M; Gilad R; et al. (2007). "Minocycline treatment in acute stroke: an open-label, evaluator-blinded study". Neurology. 69 (14): 1404–10. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000277487.04281.db. PMID 17909152.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ "How ARESTIN is supplied and dosed". OraPharma, Inc. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ^ Dean, OM (2012 May 1). "Minocycline: therapeutic potential in psychiatry". CNS drugs. 26 (5): 391–401. PMID 22486246.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- New Zealand Datasheet May 2002

- Minocycline on drugs.com

- Minocycline on medicinenet.com

- Minocycline to Treat Childhood Regressive Autism [1]

- Minocycline for acne