Neonicotinoid: Difference between revisions

→Links to decline in bee population: There are multiple primary symptoms of CCD, so being careful about language here. |

→Links to decline in bee population: Adding review of first documentations of CDD |

||

| Line 151: | Line 151: | ||

===Links to decline in bee population === |

===Links to decline in bee population === |

||

A world-wide dramatic rise in the number of beehive losses and a reduction of wild bees was noticed around 2006.<ref>{{cite news |first=Jasper |last=Copping |date=April 1, 2007 |title=Flowers and fruit crops facing disaster as disease kills off bees |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1547243/Flowers-and-fruit-crops-facing-disaster-as-disease-kills-off-bees.html |work=The Telegraph}}</ref> When first introduced neonicotinoids were thought to have low-toxicity to many insects, but recent research has suggested a potential toxicity to honey bees and other beneficial insects even with low levels of contact. Neonicotinoids may impact bees’ ability to forage, learn and remember navigation routes to and from food sources.<ref>[http://citybugs.tamu.edu/factsheets/ipm/what-is-a-neonicotinoid/ What is a neonicotinoid? | Insects in the City]. Citybugs.tamu.edu. Retrieved on 2013-05-02.</ref> Neonicotinoids may be responsible for detrimental effects on [[bumble bee]] colony growth and queen production.<ref name="Sci-bees">{{cite doi|10.1126/science.1215025}}</ref> |

A world-wide dramatic rise in the number of annual beehive losses and a reduction of wild bees was noticed around 2006.<ref>{{cite news |first=Jasper |last=Copping |date=April 1, 2007 |title=Flowers and fruit crops facing disaster as disease kills off bees |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1547243/Flowers-and-fruit-crops-facing-disaster-as-disease-kills-off-bees.html |work=The Telegraph}}</ref><ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0006481}}</ref> When first introduced neonicotinoids were thought to have low-toxicity to many insects, but recent research has suggested a potential toxicity to honey bees and other beneficial insects even with low levels of contact. Neonicotinoids may impact bees’ ability to forage, learn and remember navigation routes to and from food sources.<ref>[http://citybugs.tamu.edu/factsheets/ipm/what-is-a-neonicotinoid/ What is a neonicotinoid? | Insects in the City]. Citybugs.tamu.edu. Retrieved on 2013-05-02.</ref> Neonicotinoids may be responsible for detrimental effects on [[bumble bee]] colony growth and queen production.<ref name="Sci-bees">{{cite doi|10.1126/science.1215025}}</ref> |

||

Neonicotinoids also have previously undetected routes of exposure affecting bees including through dust, pollen and nectar<ref>{{cite doi|10.1021/es2035152}}</ref> and that sub-nanogram toxicity can result in failure to return to the hive without immediate lethality,<ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0030023}}</ref> one primary symptom of colony collapse disorder.<ref>{{cite pmid|22246149}}</ref> Separate research showed environmental persistence in agricultural [[irrigation]] channels and soil.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0029268}}</ref> |

Neonicotinoids also have previously undetected routes of exposure affecting bees including through dust, pollen and nectar<ref>{{cite doi|10.1021/es2035152}}</ref> and that sub-nanogram toxicity can result in failure to return to the hive without immediate lethality,<ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0030023}}</ref> one primary symptom of colony collapse disorder.<ref>{{cite pmid|22246149}}</ref> Separate research showed environmental persistence in agricultural [[irrigation]] channels and soil.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0029268}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 06:08, 12 June 2014

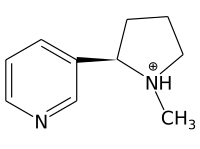

Neonicotinoids are a class of neuro-active insecticides chemically similar to nicotine. The development of this class of insecticides began with work in the 1980s by Shell and the 1990s by Bayer.[1] The neonicotinoids show reduced toxicity compared to previously used organophosphate and carbamate insecticides. Most neonicotinoids show much lower toxicity in mammals than insects, but some breakdown products are toxic.[2] Neonicotinoids are the first new class of insecticides to be developed in the last 50 years. The neonicotinoid imidacloprid is currently the most widely used insecticide in the world.[3] The neonicotinoid family includes acetamiprid, clothianidin, imidacloprid, nitenpyram, nithiazine, thiacloprid and thiamethoxam.

The use of some members of this class has been restricted in some countries due to some evidence of a connection to honey-bee colony collapse disorder (CCD).[4][5][6]

In March 2013, the American Bird Conservancy published a review of 200 studies on neonicotinoids, including industry research obtained through the US Freedom of Information Act. It called for a ban on neonicotinoid use as seed treatments because of their toxicity to birds, aquatic invertebrates, and other wildlife.[7]

Market

Neonicotinoids are registered in more than 120 countries. With a turnover of €1.5 billion, they represented 24% of the global market for insecticides in 2008. Neonicotinoids are even more important in the market for seed treatments. After the introduction of the first neonicotinoids in the 1990s, this market has grown from €155 million in 1990 to €957 million in 2008. Neonicotinoids made up 80% of all seed treatment sales in 2008.[8]

Eight neonicotinoids from different companies are currently on the market.[8]

| Name | Company | Products | Turnover in million US$ (2009) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imidacloprid | Bayer CropScience | Confidor, Admire, Gaucho, Advocate | 1,091 |

| Thiamethoxam | Syngenta | Actara, Platinum, Cruiser | 627 |

| Clothianidin | Sumitomo Chemical/Bayer CropScience | Poncho, Dantosu, Dantop | 439 |

| Acetamiprid | Nippon Soda | Mospilan, Assail, ChipcoTristar | 276 |

| Thiacloprid | Bayer CropScience | Calypso | 112 |

| Dinotefuran | Mitsui Chemicals | Starkle, Safari, Venom | 79 |

| Sulfoxaflor | Dow Agrosciences | Transform, Closer | N/A |

| Nitenpyram | Sumitomo Chemical | Capstar, Bestguard | 8 |

History

Nicotine acts as an insecticide, but is more toxic to mammals,[9] with a lower lethal dose for rats than flies.[3] This spurred a search for insecticidal compounds that have selectively less effect on mammals. Initial investigation of nicotine-related compounds (nicotinoids) as insecticides was not successful.[9]

The precursor to nithiazine was first synthesized by a chemist at Purdue University. Shell researchers found in screening that this precursor showed insecticide potential and refined it to develop nithiazine.[1] Nithiazine was later found to be a postsynaptic acetylcholine receptor agonist,[10] the same mode of action as nicotine. Nithiazine does not act as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor,[10] in contrast to the organophosphate and carbamate insecticides.

While nithiazine has the desired specificity (i.e. low mammalian toxicity), it is not photostable (it breaks down in sunlight), so it was not commercially viable.

The first commercial neonicotinoid, imidacloprid, was developed by Bayer.[1]

Most neonicotinoids are water-soluble and break down slowly in the environment, so they can be taken up by the plant and provide protection from insects as the plant grows. During the late 1990s this class of pesticides, primarily imidacloprid, became widely used. Beginning in the early 2000s, two other neonicotinoids, clothianidin and thiamethoxam entered the market. Currently, virtually all corn that is planted in the Midwestern United States is treated with one of these two insecticides (and various fungicides). Most soybean seeds are treated with a neonicotinoid insecticide, usually thiamethoxam.

Regulation

United States

The US EPA operates a 15-year registration review cycle for all pesticides.[11] The EPA granted a conditional registration to clothianidin in 2003.[12] The EPA issues conditional registrations when a pesticide meets the standard for registration, but there are outstanding data requirements.[13] Thiamethoxam is approved for use as an antimicrobial pesticide wood preservative and as an agricultural pesticide; it was first approved in 1999.[14]: 4 & 14 Imidacloprid was registered in 1994.[15]

As all neonicotinoids were registered after 1984, they were not subject to reregistration, but due to environmental concerns, especially concerning bees, the EPA opened dockets to evaluate them.[16] The registration review docket for imidacloprid opened in December 2008, and the docket for nithiazine opened in March 2009. To best take advantage of new research as it becomes available, the EPA moved ahead the docket openings for the remaining neonicotinoids on the registration review schedule (acetamiprid, clothianidin, dinotefuran, thiacloprid, and thiamethoxam) to FY 2012.[16] The EPA has said that it expects to complete the review for the neonicotinoids in 2018.[17]

In March 2012, the Center for Food Safety, Pesticide Action Network, Beyond Pesticides and a group of beekeepers filed an Emergency Petition with the EPA asking the agency to suspend the use of clothianidin. The agency denied the petition.[17] In March 2013, the US EPA was sued by the same group, with the Sierra Club and the Center for Environmental Health joining, which accused the agency of performing inadequate toxicity evaluations and allowing insecticide registration based on inadequate studies.[17][18] The case, Ellis et al v. Bradbury et al, was stayed as of October 2013.[19]

On July 12, 2013, Rep. John Conyers, on behalf of himself and Rep. Earl Blumenauer, introduced the "Save American Pollinators Act" in the House of Representatives. The Act called for suspension of the use of four neonicotinoids, including the three recently suspended by the European Union, until their review is complete, and for a joint Interior Department and EPA study of bee populations and the possible reasons for their decline.[20] The bill was was assigned to a congressional committee on July 16, 2013 and did not leave committee.[21]

Europe

In 2008, Germany revoked the registration of clothianidin for use on seed corn after an incident that resulted in the death of millions of nearby honey bees.[22] An investigation revealed that it was caused by a combination of factors:

- failure to use a polymer seed coating known as a "sticker";

- weather conditions that resulted in late planting when nearby canola crops were in bloom;

- a particular type of air-driven equipment used to sow the seeds which apparently blew clothianidin-laden dust off the seeds and into the air as the seeds were ejected from the machine into the ground;

- dry and windy conditions at the time of planting that blew the dust into the nearby canola fields where honey bees were foraging;[23]

In Germany, clothianidin was also restricted for a short period from use on rapeseed; however, after evidence had shown that the problems resulting from maize seed were not transferable to rapeseed, its use was reinstated under the condition that the pesticide be fixed to the rapeseed grains by means of an additional sticker, so that abrasion dusts would not be released into the air.[24][25]

In 2009, the German Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety decided to continue to suspend authorization for the use of clothianidin on corn. It had not yet been fully clarified to what extent and in what manner bees come into contact with the active substances in clothianidin, thiamethoxam and imidacloprid when used on corn. In addition, the question of whether liquid emitted by plants via guttation, which is taken in by bees, pose an additional risk.[26]

Neonicotinoid seed treatment uses are banned in Italy, but foliar uses are allowed. This action was taken based on preliminary monitoring studies showing that bee losses were correlated with the application of seeds treated with these compounds; Italy based its decision on the known acute toxicity of these compounds to pollinators.[27][28]

Sunflower and corn seed treatments of the active ingredient imidacloprid are suspended in France; other imidacloprid seed treatments, such as for sugar beets and cereals, are allowed, as are foliar uses.[27]

In response to growing concerns about the impact of neonicotinoids on honey bees, the European Commission in 2012 asked the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to study the safety of three neonicotinoids. The study was published in January 2013, which stated in January 2013 that neonicotinoids pose an unacceptably high risk to bees, and that the industry-sponsored science upon which regulatory agencies' claims of safety have relied may be flawed and contain data gaps not previously considered. Their review concluded, "A high acute risk to honey bees was identified from exposure via dust drift for the seed treatment uses in maize, oilseed rape and cereals. A high acute risk was also identified from exposure via residues in nectar and/or pollen."[29][30] EFSA reached the following conclusions:[31][32]

- Exposure from pollen and nectar. Only uses on crops not attractive to honey bees were considered acceptable.

- Exposure from dust. A risk to honey bees was indicated or could not be excluded, with some exceptions, such as use on sugar beet and crops planted in glasshouses, and for the use of some granules.

- Exposure from guttation. The only completed assessment was for maize treated with thiamethoxam. In this case, field studies showed an acute effect on honey bees exposed to the substance through guttation fluid.

EFSA’s scientists were unable to finalize risk assessments for some uses authorized in the EU, and identified a number of data gaps. EFSA also highlighted that risk to other pollinators should be further considered. The UK Parliament asked manufacturer Bayer Cropscience to explain discrepancies in evidence that they submitted to an investigation.[33]

In response to the study, the European Commission recommended a restriction of their use across the European Union.[6]

On 29 April 2013, 15 of the 27 European Union member states voted to restrict the use of three neonicotinoids for two years from 1 December 2013. Eight nations voted against the ban, while four abstained. The law restricts the use of imidacloprid, clothianidin and thiamethoxam for seed treatment, soil application (granules) and foliar treatment in crops attractive to bees.[5][6] Temporary suspensions had previously been enacted in France, Germany and Italy.[34] In Switzerland, where neonicotinoids were never used in alpine areas, neonics were banned due to accidental poisonings of bee populations and the relatively low safety margin for other beneficial insects.[35]

Environmentalists called the move "a significant victory for common sense and our beleaguered bee populations" and said it is "crystal clear that there is overwhelming scientific, political and public support for a ban."[6] The United Kingdom, which voted against the bill, disagreed: "Having a healthy bee population is a top priority for us, but we did not support the proposal for a ban because our scientific evidence doesn’t support it."[6] Bayer Cropscience, which makes two of the three banned products, remarked "Bayer remains convinced neonicotinoids are safe for bees, when used responsibly and properly ... clear scientific evidence has taken a back-seat in the decision-making process."[34] Reaction in the scientific community was mixed. Biochemist Lin Field said the decision was based on "political lobbying" and could lead to the overlooking of other factors involved in colony collapse disorder. Zoologist Lynn Dicks of Cambridge University disagreed, saying "This is a victory for the precautionary principle, which is supposed to underlie environmental regulation."[6] A bee expert called the ban "excellent news for pollinators", and said, "The weight of evidence from researchers clearly points to the need to have a phased ban of neonicotinoids."[34]

Economic impact

In January 2013, the Humboldt Forum for Food and Agriculture e. V. (HFFA) published a report on the value of neonicotinoids in the EU. The study was commissioned by Bayer CropScience and Syngenta. COPA-COGECA, the European Seed Association and the European Crop Protection Association supported it. The report looked at the short- and medium-term impacts of a complete ban of all neonicotinoids on agricultural and total value added (VA) and employment, global prices, land use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In the first year, agricultural and total VA would decline by €2.8 and €3.8 billion, respectively. The greatest losses would be in wheat, maize and rapeseed in the UK, Germany, Romania and France. 22,000 jobs would be lost, primarily in Romania and Poland, and agricultural incomes would go down by 4.7%. In the medium-term (5-year ban), losses would amount to €17 billion in VA, and 27,000 jobs. The greatest income losses would affect the UK, while most jobs losses would occur in Romania. Following a ban, the lowered production would induce more imports of agricultural commodities into the EU. Agricultural production outside the EU would expand by 3.3 million hectares, leading to additional emissions of 600 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent.[36]

Usage

Imidacloprid is effective against sucking insects, some chewing insects, soil insects and is also used to control fleas on domestic animals.[37] It is possibly the most widely used insecticide, both within the neonics and in the worldwide market. It is now applied against soil, seed, timber and animal pests as well as foliar treatments for crops including: cereals, cotton, grain, legumes, potatoes,[38] pome fruits, rice, turf and vegetables. It is systemic with particular efficacy against sucking insects and has a long residual activity. Imidacloprid can be added to the water used to irrigate plants. Controlled release formulations of imidacloprid take 2–10 days to release 50% of imidacloprid in water.[39]

The application rates for neonicotinoid insecticides are much lower than older, traditionally used insecticides.[citation needed]

Mode of action

Neonicotinoids, like nicotine, bind to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of a cell and trigger a response by that cell. In mammals, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are located in cells of both the central and peripheral nervous systems. In insects these receptors are limited to the CNS.

While low to moderate activation of these receptors causes nervous stimulation, high levels overstimulate and block the receptors,[3][37] causing paralysis and death. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are activated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Acetylcholine is broken down by acetylcholinesterase to terminate signals from these receptors. However, acetylcholinesterase cannot break down neonicotinoids and the binding is irreversible.[37] Because most neonicotinoids bind much more strongly to insect neuron receptors than to mammal neuron receptors, these insecticides are selectively more toxic to insects than mammals.[40]

Basis of selectivity

Most neonicotinoids, such as imidacloprid, show low affinity for mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) while exhibiting high affinity for insect nAChRs.[3][41] Mammals and insects have structural differences in nAChRs that affect how strongly particular molecules bind, both in the composition of the receptor subunits and the structures of the receptors themselves.[40][41] The low mammalian toxicity of imidacloprid can be explained in large part by its lack of a charged nitrogen atom at physiological pH. The uncharged molecule can penetrate the insect blood–brain barrier, while the human blood–brain barrier filters it.[3]

Nicotine, like the natural ligand acetylcholine, has a positively charged nitrogen (N) atom at physiological pH.[3][40] This positive charge gives nicotine a strong affinity to mammalian nAChRs as it binds to the same negatively charged site as acetylcholine (which is positively charged like nicotine. Although the blood–brain barrier reduces access of ions to the central nervous system, nicotine is highly lipophilic and at physiological pH is quickly and widely distributed. This can be demonstrated by the fact that nicotine is well absorbed transdermally, one of the most difficult tissues to penetrate. Neonicotinoids, on the other hand, have a negatively charged nitro or cyano group, which interacts with a unique, positively charged amino acid residue present on insect, but not mammalian nAChRs.[42]

However, desnitro-imidacloprid, which is formed in a mammal's body during metabolism[40] as well as in environmental breakdown,[43] has a charged nitrogen and shows high affinity to mammalian nAChRs.[40] Desnitro-imidacloprid is quite toxic to mice.[2]

Independent studies show that the photodegradation half-life time of most neonicotinoids is around 34 days when exposed to sunlight. However, it might take up to 1,386 days (3.8 years) for these compounds to degrade in the absence of sunlight and micro-organism activity. Some researchers are concerned that neonicotinoids applied agriculturally might accumulate in aquifers.[44]

Environmental effects

In March 2013, the American Bird Conservancy published a review of 200 studies on neonicotinoids including industry research obtained through the US Freedom of Information Act, calling for a ban on neonicotinoid use as seed treatments because of their toxicity to birds, aquatic invertebrates, and other wildlife.[7] A Dutch study determined that water containing allowable concentrations of neonicotinoids had 50% fewer invertebrate species compared with uncontaminated water.[45]

Links to decline in bee population

A world-wide dramatic rise in the number of annual beehive losses and a reduction of wild bees was noticed around 2006.[46][47] When first introduced neonicotinoids were thought to have low-toxicity to many insects, but recent research has suggested a potential toxicity to honey bees and other beneficial insects even with low levels of contact. Neonicotinoids may impact bees’ ability to forage, learn and remember navigation routes to and from food sources.[48] Neonicotinoids may be responsible for detrimental effects on bumble bee colony growth and queen production.[49]

Neonicotinoids also have previously undetected routes of exposure affecting bees including through dust, pollen and nectar[50] and that sub-nanogram toxicity can result in failure to return to the hive without immediate lethality,[51] one primary symptom of colony collapse disorder.[52] Separate research showed environmental persistence in agricultural irrigation channels and soil.[53]

A 2012 study showed the presence of two neonicotinoid insecticides, clothianidin and thiamethoxam, in bees found dead in and around hives situated near agricultural fields. Other bees at the hives exhibited tremors, uncoordinated movement and convulsions, all signs of insecticide poisoning. The insecticides were also consistently found at low levels in soil up to two years after treated seed was planted and on nearby dandelion flowers and in corn pollen gathered by the bees. Insecticide-treated seeds are covered with a sticky substance to control its release into the environment, however they are then coated with talc to facilitate machine planting. This talc may be released into the environment in large amounts. The study found that the exhausted talc showed up to about 700,000 times the lethal insecticide dose for a bee. Exhausted talc containing the insecticides is concentrated enough that even small amounts on flowering plants can kill foragers or be transported to the hive in contaminated pollen. Tests also showed that the corn pollen that bees were bringing back to hives tested positive for neonicotinoids at levels roughly below 100 parts per billion, an amount not acutely toxic, but enough to kill bees if sufficient amounts are consumed.[54]

An October 2013 study by Italian researchers demonstrated that neonicotinoids disrupt the innate immune systems of bees, making them susceptible to viral infections to which the bees are normally resistant.[55][56]

References

- ^ a b c Kollmeyer, Willy D.; Flattum, Roger F.; Foster, James P.; Powell, James E.; Schroeder, Mark E.; Soloway, S. Barney (1999). "Discovery of the Nitromethylene Heterocycle Insecticides". In Yamamoto, Izuru; Casida, John (eds.). Nicotinoid Insecticides and the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. pp. 71–89. ISBN 443170213X.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1006/pest.1997.2284, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1006/pest.1997.2284instead. - ^ a b c d e f Yamamoto, Izuru (1999). "Nicotine to Nicotinoids: 1962 to 1997". In Yamamoto, Izuru; Casida, John (eds.). Nicotinoid Insecticides and the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. pp. 3–27. ISBN 443170213X.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/496408a, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/496408ainstead.

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/nature11585, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with|doi=10.1038/nature11585instead.

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/494283a, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with|doi=10.1038/494283ainstead.

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11626, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with|doi=10.1038/nature.2012.11626instead.

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/nature11637, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with|doi=10.1038/nature11637instead.

Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/nature.2013.12234, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with|doi=10.1038/nature.2013.12234instead.

"Nature Studies by Michael McCarthy: Have we learned nothing since 'Silent Spring'?" The Independent 7 January 2011

"Do people know perfectly well what’s killing bees?" IO9.com 6 January 2011 - ^ a b Bees & Pesticides: Commission goes ahead with plan to better protect bees. 30 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Charlotte McDonald-Gibson (29 April 2013). "'Victory for bees' as European Union bans neonicotinoid pesticides blamed for destroying bee population". The Independent. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ a b Pierre Mineau (March 2013). "The Impact of the Nation's Most Widely Used Insecticides on Birds" (PDF). Neonicotinoid Insecticides and Birds. American Bird Conservancy. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Peter Jeschke, Ralf Nauen, Michael Schindler, Alfred Elbert, 2011. Overview of the Status and Global Strategy for Neonicotinoids. Journals of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 59: 2897-2908.

- ^ a b Ujváry, István (1999). "Nicotine and Other Insecticidal Alkaloids". In Yamamoto, Izuru; Casida, John (eds.). Nicotinoid Insecticides and the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. pp. 29–69. ISBN 443170213X.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/0048-3575(84)90084-1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/0048-3575(84)90084-1instead. - ^ EPA Registration Review Process Last updated on April 17, 2014. Page accessed June 7, 2014

- ^ EPA http://www.epa.gov/opp00001/chem_search/reg_actions/registration/fs_PC-044309_30-May-03.pdf Pesticide Fact Sheet: Clothianidin] Conditional Registration, Issued May 30, 2003

- ^ EPA Conditional Pesticide Registration Last updated on April 17, 2014. Page accessed June 7, 2014

- ^ EPA Dec 21, 2011 Thiamethoxam Summary Document Registration Review Initial Docket Entire docket is available here

- ^ EPA Dec 17, 2008 Imidacloprid Summary Document. Entire docket is available here

- ^ a b EPA Groups of Pesticides in Registration Review: Neonicotinoids Last updated on April 17, 2014. Page accessed June 7, 2014

- ^ a b c Press release: Pesticide Action Network, Center for Food Safety, and Beyond Pesticides. March 21, 2013 Beekeepers and Public Interest Groups Sue EPA Over Bee-Toxic Pesticides

- ^ Carrington, Damian (22 March 2013). "US government sued over use of pesticides linked to bee harm". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Justia Dockets & Filings. Ellis et al v. Bradbury et al Page accessed June 7, 2014

- ^ "Legislation to restrict pesticide use proposed by Rep. Blumenauer". The Oregonian at 'OregonLive'. July 12, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ Govtrack.us H.R. 2692: Saving America’s Pollinators Act of 2013 Accessed June 7, 2014

- ^ Benjamin, Alison (23 May 2008). "Pesticides: Germany bans chemicals linked to honeybee devastation". The Guardian.

- ^ "EPA Acts to Protect Bees | Pesticides | US EPA". Epa.gov. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ "Press releases and background information – Background information: Bee losses caused by insecticidal seed treatment in Germany in 2008". BVL. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ "Background information: Bee losses caused by insecticidal seed treatment in Germany in 2008". German Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety (BVL). 2008-07-15.

- ^ "Maize seed may now be treated with "Mesurol flüssig" again". German Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety (BVL). 2002-02-09.

- ^ a b "Colony Collapse Disorder: European Bans on Neonicotinoid Pesticides | Pesticides | US EPA". Epa.gov. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ Brandon Keim (Dec 13, 2010). "Leaked Memo Shows EPA Doubts About Bee-Killing Pesticide". Wired.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (16 January 2013) "Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment for bees for the active substance clothianidin" EFSA Journal 11(1):3066.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (2012) "Assessment of the scientific information from the Italian project 'APENET' investigating effects on honeybees of coated maize seeds with some neonicotinoids and fipronil" EFSA Journal 10(6):2792

- ^ EFSA: EFSA identifies risks to bees from neonicotinoids. 16 January 2013.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (16 January 2013) "Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment for bees for the active substance clothianidin" EFSA Journal 11(1):3066.

- ^ Damian Carrington (16 January 2013) "Insecticide 'unacceptable' danger to bees, report finds" The Guardian

- ^ a b c Damian Carrington (29 April 2013). "Bee-harming pesticides banned in Europe". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ S. Kusma (May 2013). "Was soll die Einschränkung der Neonicotinoide bringen?" (in German). Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ Steffen Noleppa, Thomas Hahn: The value of Neonicotinoid seed treatment in the European Union: A socio-economic, technological and environmental review. Humboldt Forum for Food and Agriculture (HFFA), 2013.

- ^ a b c Gervais, J.A.; Luukinen, B.; Buhl, K.; Stone, D. (April 2010). "Imidacloprid Technical Fact Sheet" (PDF). National Pesticide Information Center. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Potato insecticides by group and mode of action (PDF)

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/03601234.2012.634365, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/03601234.2012.634365instead. - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1584/jpestics.29.177, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1584/jpestics.29.177instead. Cite error: The named reference "Tomizawa2004" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Tomizawa, Motohiro; Latli, Bachir; Casida, John E. (1999). "Structure and Function of Insect Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Studied with Nicotinic Insecticide Affinity Probes". In Yamamoto, Izuru; Casida, John (eds.). Nicotinoid Insecticides and the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. pp. 271–292. ISBN 443170213X.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112731, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112731instead. - ^ Koshlukova, Svetlana (9 February 2006). "Imidacloprid: Risk Characterization Document: Dietary and Drinking Water Exposure" (PDF). California Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Pesticide Regulation. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ "Interview with microbiologist: "This place is filled with multinational lobbyists"". Delo.si. 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ "Study links insecticide use to invertebrate die-offs". www.guardian.com. 2013-05-01. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ Copping, Jasper (April 1, 2007). "Flowers and fruit crops facing disaster as disease kills off bees". The Telegraph.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006481, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0006481instead. - ^ What is a neonicotinoid? | Insects in the City. Citybugs.tamu.edu. Retrieved on 2013-05-02.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1215025, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1215025instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/es2035152, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/es2035152instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030023, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0030023instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22246149, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22246149instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029268, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0029268instead. - ^ Purdue Newsroom – Researchers: Honeybee deaths linked to seed insecticide exposure. Purdue.edu (2012-01-11). Retrieved on 2013-05-02.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1073/pnas.1314923110, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1073/pnas.1314923110instead. - ^ Timmer, John (21 October 2013). "An insecticide-infection connection in bee colony collapses". Ars Technica. Retrieved 22 October 2013.