Tuberculosis: Difference between revisions

Added free to read links in citations with OAbot #oabot |

Rescuing 68 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.5.1) |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

||

'''Tuberculosis''' ('''TB''') is an [[infectious disease]] caused by the bacterium ''[[Mycobacterium tuberculosis]]'' (MTB).<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> Tuberculosis generally affects the [[lung]]s, but can also affect other parts of the body.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> Most infections do not have symptoms, in which case it is known as [[latent tuberculosis]].<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> About 10% of latent infections progress to active disease which, if left untreated, kills about half of those infected.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> The classic symptoms of active TB are a chronic [[cough]] with [[hemoptysis|blood-containing]] [[sputum]], [[fever]], [[night sweats]], and [[weight loss]].<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> The historical term "'''consumption'''" came about due to the weight loss.<ref name=Cha1998>{{cite book|title=The Chambers Dictionary.|year=1998|publisher=Allied Chambers India Ltd.|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-86062-25-8|pages=352|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pz2ORay2HWoC&pg=RA1-PA352}}</ref> Infection of other organs can cause a wide range of symptoms.<ref name=ID10>{{cite book|last=Dolin|first=[edited by] Gerald L. Mandell, John E. Bennett, Raphael|title=Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases|year=2010|publisher=Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier|location=Philadelphia, PA|isbn=978-0-443-06839-3|pages=Chapter 250|edition=7th}}</ref> |

'''Tuberculosis''' ('''TB''') is an [[infectious disease]] caused by the bacterium ''[[Mycobacterium tuberculosis]]'' (MTB).<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> Tuberculosis generally affects the [[lung]]s, but can also affect other parts of the body.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> Most infections do not have symptoms, in which case it is known as [[latent tuberculosis]].<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> About 10% of latent infections progress to active disease which, if left untreated, kills about half of those infected.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> The classic symptoms of active TB are a chronic [[cough]] with [[hemoptysis|blood-containing]] [[sputum]], [[fever]], [[night sweats]], and [[weight loss]].<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> The historical term "'''consumption'''" came about due to the weight loss.<ref name=Cha1998>{{cite book|title=The Chambers Dictionary.|year=1998|publisher=Allied Chambers India Ltd.|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-86062-25-8|pages=352|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pz2ORay2HWoC&pg=RA1-PA352|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906201311/https://books.google.com/books?id=pz2ORay2HWoC&pg=RA1-PA352|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Infection of other organs can cause a wide range of symptoms.<ref name=ID10>{{cite book|last=Dolin|first=[edited by] Gerald L. Mandell, John E. Bennett, Raphael|title=Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases|year=2010|publisher=Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier|location=Philadelphia, PA|isbn=978-0-443-06839-3|pages=Chapter 250|edition=7th}}</ref> |

||

<!-- Cause and diagnosis --> |

<!-- Cause and diagnosis --> |

||

Tuberculosis is [[Airborne disease|spread through the air]] when people who have active TB in their lungs cough, spit, speak, or sneeze.<ref name=WHO2015Fact/><ref name=CDC2012B>{{cite web|title=Basic TB Facts|url=http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.htm|website=CDC|accessdate=11 February 2016|date=March 13, 2012}}</ref> People with latent TB do not spread the disease.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> Active infection occurs more often in people with [[HIV/AIDS]] and in those who [[Tobacco smoking|smoke]].<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> Diagnosis of active TB is based on [[chest X-ray]]s, as well as [[microscopic]] examination and [[microbiological culture|culture]] of body fluids.<!-- <ref name=AP/> --> Diagnosis of latent TB relies on the [[Mantoux test|tuberculin skin test]] (TST) or blood tests.<ref name=AP>{{cite journal |author=Konstantinos A |year=2010 |title=Testing for tuberculosis |journal=Australian Prescriber |volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=12–18 |url=http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/33/1/12/18/ |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100804052035/http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/33/1/12/18 |archivedate=4 August 2010 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

Tuberculosis is [[Airborne disease|spread through the air]] when people who have active TB in their lungs cough, spit, speak, or sneeze.<ref name=WHO2015Fact/><ref name=CDC2012B>{{cite web|title=Basic TB Facts|url=http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.htm|website=CDC|accessdate=11 February 2016|date=March 13, 2012|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160206032136/http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.htm|archivedate=6 February 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref> People with latent TB do not spread the disease.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> Active infection occurs more often in people with [[HIV/AIDS]] and in those who [[Tobacco smoking|smoke]].<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> Diagnosis of active TB is based on [[chest X-ray]]s, as well as [[microscopic]] examination and [[microbiological culture|culture]] of body fluids.<!-- <ref name=AP/> --> Diagnosis of latent TB relies on the [[Mantoux test|tuberculin skin test]] (TST) or blood tests.<ref name=AP>{{cite journal |author=Konstantinos A |year=2010 |title=Testing for tuberculosis |journal=Australian Prescriber |volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=12–18 |url=http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/33/1/12/18/ |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100804052035/http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/33/1/12/18 |archivedate=4 August 2010 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

||

<!-- Prevention and treatment --> |

<!-- Prevention and treatment --> |

||

Prevention of TB involves screening those at high risk, early detection and treatment of cases, and [[vaccination]] with the [[bacillus Calmette-Guérin]] vaccine.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hawn|first1=TR|last2=Day|first2=TA|last3=Scriba|first3=TJ|last4=Hatherill|first4=M|last5=Hanekom|first5=WA|last6=Evans|first6=TG|last7=Churchyard|first7=GJ|last8=Kublin|first8=JG|last9=Bekker|first9=LG|last10=Self|first10=SG|title=Tuberculosis vaccines and prevention of infection.|journal=Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR|date=December 2014|volume=78|issue=4|pages=650–71|pmid=25428938|doi=10.1128/MMBR.00021-14|pmc=4248657}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Harris|first1=Randall E.|title=Epidemiology of chronic disease: global perspectives|date=2013|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|location=Burlington, MA|isbn=9780763780470|page=682|ref=https://books.google.ca/books?id=KJLEIvX4wzoC&pg=PA682}}</ref><ref name=TBCon2008>{{cite book|last1=Organization|first1=World Health|title=Implementing the WHO Stop TB Strategy: a handbook for national TB control programmes|date=2008|publisher=World Health Organization|location=Geneva|isbn=9789241546676|page=179|url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=EUZXFCrlUaEC&pg=PA179}}</ref> Those at high risk include household, workplace, and social contacts of people with active TB.<ref name=TBCon2008/> Treatment requires the use of multiple [[antibiotic]]s over a long period of time.<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> [[Antibiotic resistance]] is a growing problem with increasing rates of [[multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis|multiple drug-resistant tuberculosis]] (MDR-TB).<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> |

Prevention of TB involves screening those at high risk, early detection and treatment of cases, and [[vaccination]] with the [[bacillus Calmette-Guérin]] vaccine.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hawn|first1=TR|last2=Day|first2=TA|last3=Scriba|first3=TJ|last4=Hatherill|first4=M|last5=Hanekom|first5=WA|last6=Evans|first6=TG|last7=Churchyard|first7=GJ|last8=Kublin|first8=JG|last9=Bekker|first9=LG|last10=Self|first10=SG|title=Tuberculosis vaccines and prevention of infection.|journal=Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR|date=December 2014|volume=78|issue=4|pages=650–71|pmid=25428938|doi=10.1128/MMBR.00021-14|pmc=4248657}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Harris|first1=Randall E.|title=Epidemiology of chronic disease: global perspectives|date=2013|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|location=Burlington, MA|isbn=9780763780470|page=682|ref=https://books.google.ca/books?id=KJLEIvX4wzoC&pg=PA682}}</ref><ref name=TBCon2008>{{cite book|last1=Organization|first1=World Health|title=Implementing the WHO Stop TB Strategy: a handbook for national TB control programmes|date=2008|publisher=World Health Organization|location=Geneva|isbn=9789241546676|page=179|url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=EUZXFCrlUaEC&pg=PA179|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160216180345/https://books.google.ca/books?id=EUZXFCrlUaEC&pg=PA179|archivedate=16 February 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Those at high risk include household, workplace, and social contacts of people with active TB.<ref name=TBCon2008/> Treatment requires the use of multiple [[antibiotic]]s over a long period of time.<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> [[Antibiotic resistance]] is a growing problem with increasing rates of [[multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis|multiple drug-resistant tuberculosis]] (MDR-TB).<ref name=WHO2015Fact/> |

||

<!-- History and epidemiology --> |

<!-- History and epidemiology --> |

||

One-third of the world's population is thought to be infected with TB.<ref name=WHO2015Fact/><!-- Quote = About one-third of the world's population has latent TB --> New infections occur in about 1% of the population each year.<ref name=WHO2002>{{cite web|title=Tuberculosis|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/who104/en/print.html|work=World Health Organization|year=2002}}</ref> In 2014, there were 9.6 million cases of active TB which resulted in 1.5 million deaths.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> More than 95% of deaths occurred in [[developing countries]].<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> The number of new cases each year has decreased since 2000.<ref name=WHO2015Fact>{{cite web|title=Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/|website=WHO|accessdate=11 February 2016|date=October 2015}}</ref> About 80% of people in many Asian and African countries test positive while 5–10% of people in the United States population tests positive by the tuberculin test.<ref name=Robbins>{{cite book |vauthors=Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN |year=2007 |title=Robbins Basic Pathology |edition=8th |publisher=Saunders Elsevier |pages=516–522 |isbn=978-1-4160-2973-1}}</ref> Tuberculosis has been present in humans since [[Ancient history|ancient times]].<ref name=Lancet11>{{cite journal|last=Lawn|first=SD|author2=Zumla, AI |title=Tuberculosis|journal=Lancet|date=2 July 2011|volume=378|issue=9785|pages=57–72|pmid=21420161|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3}}</ref> |

One-third of the world's population is thought to be infected with TB.<ref name=WHO2015Fact/><!-- Quote = About one-third of the world's population has latent TB --> New infections occur in about 1% of the population each year.<ref name=WHO2002>{{cite web|title=Tuberculosis|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/who104/en/print.html|work=World Health Organization|year=2002|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130617193438/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/who104/en/print.html|archivedate=17 June 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In 2014, there were 9.6 million cases of active TB which resulted in 1.5 million deaths.<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> More than 95% of deaths occurred in [[developing countries]].<!-- <ref name=WHO2015Fact/> --> The number of new cases each year has decreased since 2000.<ref name=WHO2015Fact>{{cite web|title=Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/|website=WHO|accessdate=11 February 2016|date=October 2015|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120823143802/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/|archivedate=23 August 2012|df=dmy-all}}</ref> About 80% of people in many Asian and African countries test positive while 5–10% of people in the United States population tests positive by the tuberculin test.<ref name=Robbins>{{cite book |vauthors=Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN |year=2007 |title=Robbins Basic Pathology |edition=8th |publisher=Saunders Elsevier |pages=516–522 |isbn=978-1-4160-2973-1}}</ref> Tuberculosis has been present in humans since [[Ancient history|ancient times]].<ref name=Lancet11>{{cite journal|last=Lawn|first=SD|author2=Zumla, AI |title=Tuberculosis|journal=Lancet|date=2 July 2011|volume=378|issue=9785|pages=57–72|pmid=21420161|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Tuberculosis video.webm|thumb|upright=1.4|Video explanation]] |

[[File:Tuberculosis video.webm|thumb|upright=1.4|Video explanation]] |

||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

{{TOC limit|3}} |

||

==Signs and symptoms== |

==Signs and symptoms== |

||

[[File:Tuberculosis symptoms.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|The main symptoms of variants and stages of tuberculosis are given,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.emedicinehealth.com/tuberculosis/page3_em.htm|title=Tuberculosis Symptoms|publisher=[[eMedicine]]Health|author=Schiffman G|date=15 January 2009}}</ref> with many symptoms overlapping with other variants, while others are more (but not entirely) specific for certain variants. Multiple variants may be present simultaneously.]] |

[[File:Tuberculosis symptoms.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|The main symptoms of variants and stages of tuberculosis are given,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.emedicinehealth.com/tuberculosis/page3_em.htm|title=Tuberculosis Symptoms|publisher=[[eMedicine]]Health|author=Schiffman G|date=15 January 2009|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090516075020/http://www.emedicinehealth.com/tuberculosis/page3_em.htm|archivedate=16 May 2009|df=dmy-all}}</ref> with many symptoms overlapping with other variants, while others are more (but not entirely) specific for certain variants. Multiple variants may be present simultaneously.]] |

||

Tuberculosis may infect any part of the body, but most commonly occurs in the lungs (known as pulmonary tuberculosis).<ref name=ID10/> Extrapulmonary TB occurs when tuberculosis develops outside of the lungs, although extrapulmonary TB may coexist with pulmonary TB.<ref name=ID10/> |

Tuberculosis may infect any part of the body, but most commonly occurs in the lungs (known as pulmonary tuberculosis).<ref name=ID10/> Extrapulmonary TB occurs when tuberculosis develops outside of the lungs, although extrapulmonary TB may coexist with pulmonary TB.<ref name=ID10/> |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

===Pulmonary=== |

===Pulmonary=== |

||

If a tuberculosis infection does become active, it most commonly involves the lungs (in about 90% of cases).<ref name=Lancet11/><ref>{{cite book|last=Behera|first=D.|title=Textbook of Pulmonary Medicine|year=2010|publisher=Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-8448-749-7|pages=457|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0TbJjd9eTp0C&pg=PA457|edition=2nd}}</ref> Symptoms may include [[chest pain]] and a prolonged cough producing sputum.<!-- <ref name=Lancet11/> --> About 25% of people may not have any symptoms (i.e. they remain "asymptomatic").<ref name=Lancet11/> Occasionally, people may [[hemoptysis|cough up blood]] in small amounts, and in very rare cases, the infection may erode into the [[pulmonary artery]] or a [[Rasmussen's aneurysm]], resulting in massive bleeding.<ref name=ID10/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Halezeroğlu|first1=S|last2=Okur|first2=E|title=Thoracic surgery for haemoptysis in the context of tuberculosis: what is the best management approach?|journal=Journal of Thoracic Disease|date=March 2014|volume=6|issue=3|pages=182–5|pmid=24624281|doi=10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.25|pmc=3949181}}</ref> Tuberculosis may become a chronic illness and cause extensive scarring in the upper lobes of the lungs.<!-- <ref name=ID10/> --> The upper lung lobes are more frequently affected by tuberculosis than the lower ones.<ref name=ID10/> The reason for this difference is not clear.<ref name="Robbins" /> It may be due to either better air flow,<ref name="Robbins" /> or poor [[lymph]] drainage within the upper lungs.<ref name=ID10/> |

If a tuberculosis infection does become active, it most commonly involves the lungs (in about 90% of cases).<ref name=Lancet11/><ref>{{cite book|last=Behera|first=D.|title=Textbook of Pulmonary Medicine|year=2010|publisher=Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-8448-749-7|pages=457|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0TbJjd9eTp0C&pg=PA457|edition=2nd|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906185549/https://books.google.com/books?id=0TbJjd9eTp0C&pg=PA457|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Symptoms may include [[chest pain]] and a prolonged cough producing sputum.<!-- <ref name=Lancet11/> --> About 25% of people may not have any symptoms (i.e. they remain "asymptomatic").<ref name=Lancet11/> Occasionally, people may [[hemoptysis|cough up blood]] in small amounts, and in very rare cases, the infection may erode into the [[pulmonary artery]] or a [[Rasmussen's aneurysm]], resulting in massive bleeding.<ref name=ID10/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Halezeroğlu|first1=S|last2=Okur|first2=E|title=Thoracic surgery for haemoptysis in the context of tuberculosis: what is the best management approach?|journal=Journal of Thoracic Disease|date=March 2014|volume=6|issue=3|pages=182–5|pmid=24624281|doi=10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.25|pmc=3949181}}</ref> Tuberculosis may become a chronic illness and cause extensive scarring in the upper lobes of the lungs.<!-- <ref name=ID10/> --> The upper lung lobes are more frequently affected by tuberculosis than the lower ones.<ref name=ID10/> The reason for this difference is not clear.<ref name="Robbins" /> It may be due to either better air flow,<ref name="Robbins" /> or poor [[lymph]] drainage within the upper lungs.<ref name=ID10/> |

||

===Extrapulmonary=== |

===Extrapulmonary=== |

||

In 15–20% of active cases, the infection spreads outside the lungs, causing other kinds of TB.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jindal|first=editor-in-chief SK|title=Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine|publisher=Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-93-5025-073-0|pages=549|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EvGTw3wn-zEC&pg=PA549|year=2011}}</ref> These are collectively denoted as "extrapulmonary tuberculosis".<ref name=Extra2005>{{cite journal|pmid=16300038|year=2005|vauthors=Golden MP, Vikram HR |title=Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview|volume=72|issue=9|pages=1761–8|journal=American Family Physician }}</ref> Extrapulmonary TB occurs more commonly in [[Immunosuppression|immunosuppressed]] persons and young children. In those with HIV, this occurs in more than 50% of cases.<ref name=Extra2005/> Notable extrapulmonary infection sites include the [[Pleural cavity|pleura]] (in tuberculous pleurisy), the [[central nervous system]] (in tuberculous [[meningitis]]), the [[lymphatic system]] (in [[Tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis|scrofula]] of the neck), the [[genitourinary system]] (in [[urogenital tuberculosis]]), and the bones and joints (in [[Pott disease]] of the spine), among others. |

In 15–20% of active cases, the infection spreads outside the lungs, causing other kinds of TB.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jindal|first=editor-in-chief SK|title=Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine|publisher=Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-93-5025-073-0|pages=549|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EvGTw3wn-zEC&pg=PA549|year=2011|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150907185434/https://books.google.com/books?id=EvGTw3wn-zEC&pg=PA549|archivedate=7 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> These are collectively denoted as "extrapulmonary tuberculosis".<ref name=Extra2005>{{cite journal|pmid=16300038|year=2005|vauthors=Golden MP, Vikram HR |title=Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an overview|volume=72|issue=9|pages=1761–8|journal=American Family Physician }}</ref> Extrapulmonary TB occurs more commonly in [[Immunosuppression|immunosuppressed]] persons and young children. In those with HIV, this occurs in more than 50% of cases.<ref name=Extra2005/> Notable extrapulmonary infection sites include the [[Pleural cavity|pleura]] (in tuberculous pleurisy), the [[central nervous system]] (in tuberculous [[meningitis]]), the [[lymphatic system]] (in [[Tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis|scrofula]] of the neck), the [[genitourinary system]] (in [[urogenital tuberculosis]]), and the bones and joints (in [[Pott disease]] of the spine), among others. |

||

Spread to [[lymph nodes]] is the most common.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Rockwood|first1=RR|title=Extrapulmonary TB: what you need to know.|journal=The Nurse practitioner|date=August 2007|volume=32|issue=8|pages=44–9|pmid=17667766|doi=10.1097/01.npr.0000282802.12314.dc}}</ref> An ulcer originating from nearby infected lymph nodes may occur and is painless, slowly enlarging and has an appearance of "wash leather".<ref>{{cite book|last=Burkitt|first=H. George|title=Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis & Management 4th ed|year=2007|isbn=9780443103452|pages=34}}</ref> |

Spread to [[lymph nodes]] is the most common.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Rockwood|first1=RR|title=Extrapulmonary TB: what you need to know.|journal=The Nurse practitioner|date=August 2007|volume=32|issue=8|pages=44–9|pmid=17667766|doi=10.1097/01.npr.0000282802.12314.dc}}</ref> An ulcer originating from nearby infected lymph nodes may occur and is painless, slowly enlarging and has an appearance of "wash leather".<ref>{{cite book|last=Burkitt|first=H. George|title=Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis & Management 4th ed|year=2007|isbn=9780443103452|pages=34}}</ref> |

||

When it spreads to the bones, it is known as "osseous tuberculosis",<ref>{{cite book|last=Kabra|first=[edited by] Vimlesh Seth, S.K.|title=Essentials of tuberculosis in children|year=2006|publisher=Jaypee Bros. Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-8061-709-6|pages=249|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HkH0YbyBHDQC&pg=PA249|edition=3rd}}</ref> a form of [[osteomyelitis]].<ref name="Robbins" /> A potentially more serious, widespread form of TB is called "disseminated tuberculosis", also known as [[miliary tuberculosis]].<ref name=ID10/> Miliary TB currently makes up about 10% of extrapulmonary cases.<ref name=Gho2008/> |

When it spreads to the bones, it is known as "osseous tuberculosis",<ref>{{cite book|last=Kabra|first=[edited by] Vimlesh Seth, S.K.|title=Essentials of tuberculosis in children|year=2006|publisher=Jaypee Bros. Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-8061-709-6|pages=249|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HkH0YbyBHDQC&pg=PA249|edition=3rd|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906204238/https://books.google.com/books?id=HkH0YbyBHDQC&pg=PA249|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> a form of [[osteomyelitis]].<ref name="Robbins" /> A potentially more serious, widespread form of TB is called "disseminated tuberculosis", also known as [[miliary tuberculosis]].<ref name=ID10/> Miliary TB currently makes up about 10% of extrapulmonary cases.<ref name=Gho2008/> |

||

==Causes== |

==Causes== |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

{{Main article| Mycobacterium tuberculosis}} |

{{Main article| Mycobacterium tuberculosis}} |

||

[[File:Mycobacterium tuberculosis.jpg|thumb|[[Scanning electron micrograph]] of ''M. tuberculosis'']] |

[[File:Mycobacterium tuberculosis.jpg|thumb|[[Scanning electron micrograph]] of ''M. tuberculosis'']] |

||

The main cause of TB is ''[[Mycobacterium tuberculosis]]'' (MTB), a small, [[aerobic organism|aerobic]], nonmotile [[bacillus]].<ref name=ID10/> The high [[lipid]] content of this pathogen accounts for many of its unique clinical characteristics.<ref>{{cite book |author=Southwick F |title=Infectious Diseases: A Clinical Short Course, 2nd ed. |publisher=McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division |date=10 December 2007 |pages=104, 313–4 |chapter=Chapter 4: Pulmonary Infections |isbn=0-07-147722-5}}</ref> It [[cell division|divides]] every 16 to 20 hours, which is an extremely slow rate compared with other bacteria, which usually divide in less than an hour.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jindal|first=editor-in-chief SK|title=Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine|publisher=Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-93-5025-073-0|pages=525|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rAT1bdnDakAC&pg=PA525|year=2011}}</ref> Mycobacteria have an [[Bacterial cell structure|outer membrane]] lipid bilayer.<ref name=Niederweis2010>{{cite journal |vauthors=Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffmann C, Engelhardt H |title=Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins |journal=Trends in Microbiology |volume=18 |issue=3 |pages=109–16 |date=March 2010 |pmid=20060722 |pmc=2931330 |doi=10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.005 }}</ref> If a [[Gram stain]] is performed, MTB either stains very weakly "Gram-positive" or does not retain dye as a result of the high lipid and [[mycolic acid]] content of its cell wall.<ref name=Madison_2001>{{cite journal |author=Madison B |title=Application of stains in clinical microbiology |journal=Biotechnic & Histochemistry |volume=76 |issue=3 |pages=119–25 |year=2001 |pmid=11475314 |doi=10.1080/714028138}}</ref> MTB can withstand weak [[disinfectant]]s and survive in a [[Endospore|dry state]] for weeks. In nature, the bacterium can grow only within the cells of a [[host (biology)|host]] organism, but ''M. tuberculosis'' can be cultured [[in vitro|in the laboratory]].<ref name=Parish_1999>{{cite journal |author1=Parish T. |author2=Stoker N. |title=Mycobacteria: bugs and bugbears (two steps forward and one step back) |journal=Molecular Biotechnology |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=191–200 |year=1999| pmid=10934532 |doi = 10.1385/MB:13:3:191}}</ref> |

The main cause of TB is ''[[Mycobacterium tuberculosis]]'' (MTB), a small, [[aerobic organism|aerobic]], nonmotile [[bacillus]].<ref name=ID10/> The high [[lipid]] content of this pathogen accounts for many of its unique clinical characteristics.<ref>{{cite book |author=Southwick F |title=Infectious Diseases: A Clinical Short Course, 2nd ed. |publisher=McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division |date=10 December 2007 |pages=104, 313–4 |chapter=Chapter 4: Pulmonary Infections |isbn=0-07-147722-5}}</ref> It [[cell division|divides]] every 16 to 20 hours, which is an extremely slow rate compared with other bacteria, which usually divide in less than an hour.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jindal|first=editor-in-chief SK|title=Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine|publisher=Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-93-5025-073-0|pages=525|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rAT1bdnDakAC&pg=PA525|year=2011|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906211342/https://books.google.com/books?id=rAT1bdnDakAC&pg=PA525|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Mycobacteria have an [[Bacterial cell structure|outer membrane]] lipid bilayer.<ref name=Niederweis2010>{{cite journal |vauthors=Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffmann C, Engelhardt H |title=Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins |journal=Trends in Microbiology |volume=18 |issue=3 |pages=109–16 |date=March 2010 |pmid=20060722 |pmc=2931330 |doi=10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.005 }}</ref> If a [[Gram stain]] is performed, MTB either stains very weakly "Gram-positive" or does not retain dye as a result of the high lipid and [[mycolic acid]] content of its cell wall.<ref name=Madison_2001>{{cite journal |author=Madison B |title=Application of stains in clinical microbiology |journal=Biotechnic & Histochemistry |volume=76 |issue=3 |pages=119–25 |year=2001 |pmid=11475314 |doi=10.1080/714028138}}</ref> MTB can withstand weak [[disinfectant]]s and survive in a [[Endospore|dry state]] for weeks. In nature, the bacterium can grow only within the cells of a [[host (biology)|host]] organism, but ''M. tuberculosis'' can be cultured [[in vitro|in the laboratory]].<ref name=Parish_1999>{{cite journal |author1=Parish T. |author2=Stoker N. |title=Mycobacteria: bugs and bugbears (two steps forward and one step back) |journal=Molecular Biotechnology |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=191–200 |year=1999| pmid=10934532 |doi = 10.1385/MB:13:3:191}}</ref> |

||

Using [[histology|histological]] stains on [[expectorate]]d samples from [[phlegm]] (also called "sputum"), scientists can identify MTB under a microscope. Since MTB retains certain stains even after being treated with acidic solution, it is classified as an [[acid-fast bacillus]].<ref name=Robbins/><ref name="Madison_2001"/> The most common acid-fast staining techniques are the [[Ziehl–Neelsen stain]]<ref name=Stain2000>{{cite book |title=Medical Laboratory Science: Theory and Practice |publisher=Tata McGraw-Hill |location=New Delhi |year=2000 |pages=473 |isbn=0-07-463223-X |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lciNs3VQPLoC&pg=PA473}}</ref> and the [[Kinyoun stain]], which dye acid-fast bacilli a bright red that stands out against a blue background.<ref>{{cite web |title=Acid-Fast Stain Protocols |url=http://www.microbelibrary.org/component/resource/laboratory-test/2870-acid-fast-stain-protocols |accessdate=26 March 2016 |date=21 August 2013 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111001132818/http://www.microbelibrary.org/component/resource/laboratory-test/2870-acid-fast-stain-protocols |archivedate=1 October 2011 |df= }}</ref> [[Auramine-rhodamine stain]]ing<ref name=Kommareddi_1984>{{cite journal|author1=Kommareddi S. |author2=Abramowsky C. |author3=Swinehart G. |author4=Hrabak L. |title=Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: comparison of the fluorescent auramine-O and Ziehl-Neelsen techniques in tissue diagnosis|journal=Human Pathology|volume=15|issue=11|pages=1085–1089|year=1984|pmid=6208117|doi=10.1016/S0046-8177(84)80253-1}}</ref> and [[Fluorescence microscope|fluorescence microscopy]]<ref>{{cite book|last1=van Lettow|first1=Monique|last2=Whalen|first2=Christopher|title=Nutrition and health in developing countries|year=2008|publisher=Humana Press|location=Totowa, N.J. (Richard D. Semba and Martin W. Bloem, eds.)|isbn=978-1-934115-24-4|pages=291|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RhH6uSQy7a4C&pg=PA291|edition=2nd}}</ref> are also used. |

Using [[histology|histological]] stains on [[expectorate]]d samples from [[phlegm]] (also called "sputum"), scientists can identify MTB under a microscope. Since MTB retains certain stains even after being treated with acidic solution, it is classified as an [[acid-fast bacillus]].<ref name=Robbins/><ref name="Madison_2001"/> The most common acid-fast staining techniques are the [[Ziehl–Neelsen stain]]<ref name=Stain2000>{{cite book |title=Medical Laboratory Science: Theory and Practice |publisher=Tata McGraw-Hill |location=New Delhi |year=2000 |pages=473 |isbn=0-07-463223-X |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lciNs3VQPLoC&pg=PA473 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906213737/https://books.google.com/books?id=lciNs3VQPLoC&pg=PA473 |archivedate=6 September 2015 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> and the [[Kinyoun stain]], which dye acid-fast bacilli a bright red that stands out against a blue background.<ref>{{cite web |title=Acid-Fast Stain Protocols |url=http://www.microbelibrary.org/component/resource/laboratory-test/2870-acid-fast-stain-protocols |accessdate=26 March 2016 |date=21 August 2013 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111001132818/http://www.microbelibrary.org/component/resource/laboratory-test/2870-acid-fast-stain-protocols |archivedate=1 October 2011 |df= }}</ref> [[Auramine-rhodamine stain]]ing<ref name=Kommareddi_1984>{{cite journal|author1=Kommareddi S. |author2=Abramowsky C. |author3=Swinehart G. |author4=Hrabak L. |title=Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: comparison of the fluorescent auramine-O and Ziehl-Neelsen techniques in tissue diagnosis|journal=Human Pathology|volume=15|issue=11|pages=1085–1089|year=1984|pmid=6208117|doi=10.1016/S0046-8177(84)80253-1}}</ref> and [[Fluorescence microscope|fluorescence microscopy]]<ref>{{cite book|last1=van Lettow|first1=Monique|last2=Whalen|first2=Christopher|title=Nutrition and health in developing countries|year=2008|publisher=Humana Press|location=Totowa, N.J. (Richard D. Semba and Martin W. Bloem, eds.)|isbn=978-1-934115-24-4|pages=291|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RhH6uSQy7a4C&pg=PA291|edition=2nd|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906215906/https://books.google.com/books?id=RhH6uSQy7a4C&pg=PA291|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> are also used. |

||

The ''M. tuberculosis'' complex (MTBC) includes four other TB-causing [[mycobacterium|mycobacteria]]: ''[[Mycobacterium bovis|M. bovis]]'', ''[[Mycobacterium africanum|M. africanum]]'', ''[[Mycobacterium canetti|M. canetti]]'', and ''[[Mycobacterium microti|M. microti]]''.<ref>{{cite journal |author=van Soolingen D. |title=A novel pathogenic taxon of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Canetti: characterization of an exceptional isolate from Africa |journal=International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology |volume=47 |issue=4 |pages=1236–45 |year=1997 |pmid=9336935 |doi=10.1099/00207713-47-4-1236 |name-list-format=vanc |display-authors=1 |last2=Hoogenboezem |first2=T. |last3=De Haas |first3=P.E.W.|last4=Hermans |first4=P.W.M. |last5=Koedam |first5=M.A. |last6=Teppema |first6=K.S. |last7=Brennan |first7=P.J.|last8=Besra |first8=G.S.|last9=Portaels |first9=F.}}</ref> ''M. africanum'' is not widespread, but it is a significant cause of tuberculosis in parts of Africa.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Niemann S. |title=Mycobacterium africanum Subtype II Is Associated with Two Distinct Genotypes and Is a Major Cause of Human Tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda |journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology |volume=40 |issue=9 |pages=3398–405 |year=2002 |pmid=12202584 |pmc=130701 |doi=10.1128/JCM.40.9.3398-3405.2002 |name-list-format=vanc |display-authors=1 |last2=Rusch-Gerdes |first2=S.|last3=Joloba |first3=M.L.|last4=Whalen |first4=C.C.|last5=Guwatudde |first5=D.|last6=Ellner |first6=J.J.|last7=Eisenach |first7=K.|last8=Fumokong |first8=N. |last9=Johnson |first9=J.L.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Niobe-Eyangoh S.N.|title=Genetic Biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex Strains from Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Cameroon |journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology |volume=41 |issue=6 |pages=2547–53 |year=2003 |pmid=12791879 |pmc=156567 |doi=10.1128/JCM.41.6.2547-2553.2003 |name-list-format=vanc |display-authors=1 |last2=Kuaban |first2=C. |last3=Sorlin |first3=P. |last4=Cunin |first4=P. |last5=Thonnon |first5=J. |last6=Sola |first6=C. |last7=Rastogi |first7=N. |last8=Vincent |first8=V. |last9=Gutierrez |first9=M.C.}}</ref> ''M. bovis'' was once a common cause of tuberculosis, but the introduction of [[pasteurisation|pasteurized milk]] has almost completely eliminated this as a public health problem in developed countries.<ref name=Robbins/><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Thoen C, Lobue P, de Kantor I |title=The importance of ''Mycobacterium bovis'' as a zoonosis |journal=Veterinary Microbiology |volume=112 |issue=2–4 |pages=339–45 |year=2006 |pmid=16387455 |doi=10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.047}}</ref> ''M. canetti'' is rare and seems to be limited to the [[Horn of Africa]], although a few cases have been seen in African emigrants.<ref>{{cite book|last=Acton|first=Q. Ashton|title=Mycobacterium Infections: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional|year=2011|publisher=ScholarlyEditions|isbn=978-1-4649-0122-5|pages=1968|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g2iFfV6uEuAC&pg=PA1968}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Pfyffer|first=GE|author2=Auckenthaler, R |author3=van Embden, JD|author4=van Soolingen, D|title=Mycobacterium canettii, the smooth variant of M. tuberculosis, isolated from a Swiss patient exposed in Africa|journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases|date=Oct–Dec 1998|volume=4|issue=4|pages=631–4|pmid=9866740|pmc=2640258|doi=10.3201/eid0404.980414}}</ref> ''M. microti'' is also rare and is seen almost only in immunodeficient people, although its [[prevalence]] may be significantly underestimated.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Panteix|first=G|author2=Gutierrez, MC |author3=Boschiroli, ML |author4=Rouviere, M |author5=Plaidy, A |author6=Pressac, D |author7=Porcheret, H |author8=Chyderiotis, G |author9=Ponsada, M |author10=Van Oortegem, K |author11=Salloum, S |author12=Cabuzel, S |author13=Bañuls, AL |author14=Van de Perre, P |author15=Godreuil, S |title=Pulmonary tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium microti: a study of six recent cases in France|journal=Journal of Medical Microbiology|date=August 2010|volume=59|issue=Pt 8|pages=984–9|pmid=20488936|doi=10.1099/jmm.0.019372-0}}</ref> |

The ''M. tuberculosis'' complex (MTBC) includes four other TB-causing [[mycobacterium|mycobacteria]]: ''[[Mycobacterium bovis|M. bovis]]'', ''[[Mycobacterium africanum|M. africanum]]'', ''[[Mycobacterium canetti|M. canetti]]'', and ''[[Mycobacterium microti|M. microti]]''.<ref>{{cite journal |author=van Soolingen D. |title=A novel pathogenic taxon of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Canetti: characterization of an exceptional isolate from Africa |journal=International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology |volume=47 |issue=4 |pages=1236–45 |year=1997 |pmid=9336935 |doi=10.1099/00207713-47-4-1236 |name-list-format=vanc |display-authors=1 |last2=Hoogenboezem |first2=T. |last3=De Haas |first3=P.E.W.|last4=Hermans |first4=P.W.M. |last5=Koedam |first5=M.A. |last6=Teppema |first6=K.S. |last7=Brennan |first7=P.J.|last8=Besra |first8=G.S.|last9=Portaels |first9=F.}}</ref> ''M. africanum'' is not widespread, but it is a significant cause of tuberculosis in parts of Africa.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Niemann S. |title=Mycobacterium africanum Subtype II Is Associated with Two Distinct Genotypes and Is a Major Cause of Human Tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda |journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology |volume=40 |issue=9 |pages=3398–405 |year=2002 |pmid=12202584 |pmc=130701 |doi=10.1128/JCM.40.9.3398-3405.2002 |name-list-format=vanc |display-authors=1 |last2=Rusch-Gerdes |first2=S.|last3=Joloba |first3=M.L.|last4=Whalen |first4=C.C.|last5=Guwatudde |first5=D.|last6=Ellner |first6=J.J.|last7=Eisenach |first7=K.|last8=Fumokong |first8=N. |last9=Johnson |first9=J.L.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Niobe-Eyangoh S.N.|title=Genetic Biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex Strains from Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Cameroon |journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology |volume=41 |issue=6 |pages=2547–53 |year=2003 |pmid=12791879 |pmc=156567 |doi=10.1128/JCM.41.6.2547-2553.2003 |name-list-format=vanc |display-authors=1 |last2=Kuaban |first2=C. |last3=Sorlin |first3=P. |last4=Cunin |first4=P. |last5=Thonnon |first5=J. |last6=Sola |first6=C. |last7=Rastogi |first7=N. |last8=Vincent |first8=V. |last9=Gutierrez |first9=M.C.}}</ref> ''M. bovis'' was once a common cause of tuberculosis, but the introduction of [[pasteurisation|pasteurized milk]] has almost completely eliminated this as a public health problem in developed countries.<ref name=Robbins/><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Thoen C, Lobue P, de Kantor I |title=The importance of ''Mycobacterium bovis'' as a zoonosis |journal=Veterinary Microbiology |volume=112 |issue=2–4 |pages=339–45 |year=2006 |pmid=16387455 |doi=10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.047}}</ref> ''M. canetti'' is rare and seems to be limited to the [[Horn of Africa]], although a few cases have been seen in African emigrants.<ref>{{cite book|last=Acton|first=Q. Ashton|title=Mycobacterium Infections: New Insights for the Healthcare Professional|year=2011|publisher=ScholarlyEditions|isbn=978-1-4649-0122-5|pages=1968|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g2iFfV6uEuAC&pg=PA1968|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906201531/https://books.google.com/books?id=g2iFfV6uEuAC&pg=PA1968|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Pfyffer|first=GE|author2=Auckenthaler, R |author3=van Embden, JD|author4=van Soolingen, D|title=Mycobacterium canettii, the smooth variant of M. tuberculosis, isolated from a Swiss patient exposed in Africa|journal=Emerging Infectious Diseases|date=Oct–Dec 1998|volume=4|issue=4|pages=631–4|pmid=9866740|pmc=2640258|doi=10.3201/eid0404.980414}}</ref> ''M. microti'' is also rare and is seen almost only in immunodeficient people, although its [[prevalence]] may be significantly underestimated.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Panteix|first=G|author2=Gutierrez, MC |author3=Boschiroli, ML |author4=Rouviere, M |author5=Plaidy, A |author6=Pressac, D |author7=Porcheret, H |author8=Chyderiotis, G |author9=Ponsada, M |author10=Van Oortegem, K |author11=Salloum, S |author12=Cabuzel, S |author13=Bañuls, AL |author14=Van de Perre, P |author15=Godreuil, S |title=Pulmonary tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium microti: a study of six recent cases in France|journal=Journal of Medical Microbiology|date=August 2010|volume=59|issue=Pt 8|pages=984–9|pmid=20488936|doi=10.1099/jmm.0.019372-0}}</ref> |

||

Other known pathogenic mycobacteria include ''[[Mycobacterium leprae|M. leprae]]'', ''[[Mycobacterium avium complex|M. avium]]'', and ''[[Mycobacterium kansasii|M. kansasii]]''. The latter two species are classified as "[[nontuberculous mycobacteria]]" (NTM). NTM cause neither TB nor [[leprosy]], but they do cause pulmonary diseases that resemble TB.<ref name=ALA_1997>{{cite journal |title=Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association |journal=American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine |volume=156 |issue=2 Pt 2 |pages=S1–25 |year=1997 |pmid = 9279284 |author=American Thoracic Society |doi=10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement }}</ref> |

Other known pathogenic mycobacteria include ''[[Mycobacterium leprae|M. leprae]]'', ''[[Mycobacterium avium complex|M. avium]]'', and ''[[Mycobacterium kansasii|M. kansasii]]''. The latter two species are classified as "[[nontuberculous mycobacteria]]" (NTM). NTM cause neither TB nor [[leprosy]], but they do cause pulmonary diseases that resemble TB.<ref name=ALA_1997>{{cite journal |title=Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association |journal=American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine |volume=156 |issue=2 Pt 2 |pages=S1–25 |year=1997 |pmid = 9279284 |author=American Thoracic Society |doi=10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement }}</ref> |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

===Risk factors=== |

===Risk factors=== |

||

{{Main article|Risk factors for tuberculosis}} |

{{Main article|Risk factors for tuberculosis}} |

||

A number of factors make people more susceptible to TB infections. The most important risk factor globally is HIV; 13% of all people with TB are infected by the virus.<ref name=WHO2011>{{cite web|title=The sixteenth global report on tuberculosis |author=World Health Organization |url=http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011/gtbr11_executive_summary.pdf |year=2011 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120906223650/http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011/gtbr11_executive_summary.pdf |archivedate=6 September 2012 |df= }}</ref> This is a particular problem in [[sub-Saharan Africa]], where rates of HIV are high.<ref>{{cite web|author=World Health Organization|url=http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/index.html|title=Global tuberculosis control–surveillance, planning, financing WHO Report 2006|accessdate=13 October 2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Chaisson|first=RE|author2=Martinson, NA |title=Tuberculosis in Africa—combating an HIV-driven crisis|journal=The New England Journal of Medicine|date=13 March 2008|volume=358|issue=11|pages=1089–92|pmid=18337598|doi=10.1056/NEJMp0800809}}</ref> Of people without HIV who are infected with tuberculosis, about 5–10% develop active disease during their lifetimes;<ref name=Pet2005>{{cite book|last1=Gibson|first1=Peter G. (ed.)|last2=Abramson|first2=Michael (ed.)|last3=Wood-Baker|first3=Richard (ed.)|last4=Volmink|first4=Jimmy (ed.)|last5=Hensley|first5=Michael (ed.)|last6=Costabel|first6=Ulrich (ed.)|title=Evidence-Based Respiratory Medicine|date=2005|publisher=BMJ Books|isbn=978-0-7279-1605-1|page=321|edition=1st|url=http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-072791605X.html}}</ref> in contrast, 30% of those coinfected with HIV develop the active disease.<ref name=Pet2005/> |

A number of factors make people more susceptible to TB infections. The most important risk factor globally is HIV; 13% of all people with TB are infected by the virus.<ref name=WHO2011>{{cite web|title=The sixteenth global report on tuberculosis |author=World Health Organization |url=http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011/gtbr11_executive_summary.pdf |year=2011 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120906223650/http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011/gtbr11_executive_summary.pdf |archivedate=6 September 2012 |df= }}</ref> This is a particular problem in [[sub-Saharan Africa]], where rates of HIV are high.<ref>{{cite web|author=World Health Organization|url=http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/index.html|title=Global tuberculosis control–surveillance, planning, financing WHO Report 2006|accessdate=13 October 2006|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20061212123736/http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/index.html|archivedate=12 December 2006|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Chaisson|first=RE|author2=Martinson, NA |title=Tuberculosis in Africa—combating an HIV-driven crisis|journal=The New England Journal of Medicine|date=13 March 2008|volume=358|issue=11|pages=1089–92|pmid=18337598|doi=10.1056/NEJMp0800809}}</ref> Of people without HIV who are infected with tuberculosis, about 5–10% develop active disease during their lifetimes;<ref name=Pet2005>{{cite book|last1=Gibson|first1=Peter G. (ed.)|last2=Abramson|first2=Michael (ed.)|last3=Wood-Baker|first3=Richard (ed.)|last4=Volmink|first4=Jimmy (ed.)|last5=Hensley|first5=Michael (ed.)|last6=Costabel|first6=Ulrich (ed.)|title=Evidence-Based Respiratory Medicine|date=2005|publisher=BMJ Books|isbn=978-0-7279-1605-1|page=321|edition=1st|url=http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-072791605X.html|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20151208072842/http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-072791605X.html|archivedate=8 December 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> in contrast, 30% of those coinfected with HIV develop the active disease.<ref name=Pet2005/> |

||

Tuberculosis is closely linked to both overcrowding and [[malnutrition]], making it one of the principal [[diseases of poverty]].<ref name=Lancet11/> Those at high risk thus include: people who inject illicit drugs, inhabitants and employees of locales where vulnerable people gather (e.g. prisons and homeless shelters), medically underprivileged and resource-poor communities, high-risk ethnic minorities, children in close contact with high-risk category patients, and health-care providers serving these patients.<ref name=Griffith_1996>{{cite journal |vauthors=Griffith D, Kerr C | title=Tuberculosis: disease of the past, disease of the present | journal=Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing | volume=11 | issue=4 | pages=240–5 | year=1996 | pmid=8964016 | doi=10.1016/S1089-9472(96)80023-2 }}</ref> |

Tuberculosis is closely linked to both overcrowding and [[malnutrition]], making it one of the principal [[diseases of poverty]].<ref name=Lancet11/> Those at high risk thus include: people who inject illicit drugs, inhabitants and employees of locales where vulnerable people gather (e.g. prisons and homeless shelters), medically underprivileged and resource-poor communities, high-risk ethnic minorities, children in close contact with high-risk category patients, and health-care providers serving these patients.<ref name=Griffith_1996>{{cite journal |vauthors=Griffith D, Kerr C | title=Tuberculosis: disease of the past, disease of the present | journal=Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing | volume=11 | issue=4 | pages=240–5 | year=1996 | pmid=8964016 | doi=10.1016/S1089-9472(96)80023-2 }}</ref> |

||

Chronic lung disease is another significant risk factor. [[Silicosis]] increases the risk about 30-fold.<ref name=table3>{{cite journal |title=Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society |journal=MMWR. Recommendations and Reports |volume=49 |issue=RR–6 |pages=1–51|date=June 2000|pmid=10881762|url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr4906a1.htm#tab3 |author1=ATS/CDC Statement Committee on Latent Tuberculosis Infection}}</ref> Those who smoke [[cigarette]]s have nearly twice the risk of TB compared to nonsmokers.<ref>{{cite journal|last=van Zyl Smit|first=RN|author2=Pai, M |author3=Yew, WW |author4=Leung, CC |author5=Zumla, A |author6=Bateman, ED |author7=Dheda, K |title=Global lung health: the colliding epidemics of tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, HIV and COPD| journal=European Respiratory Journal |date=January 2010|volume=35|issue=1|pages=27–33|pmid=20044459|quote=These analyses indicate that smokers are almost twice as likely to be infected with TB and to progress to active disease (RR of about 1.5 for latent TB infection (LTBI) and RR of ∼2.0 for TB disease). Smokers are also twice as likely to die from TB (RR of about 2.0 for TB mortality), but data are difficult to interpret because of heterogeneity in the results across studies.|doi=10.1183/09031936.00072909}}</ref> |

Chronic lung disease is another significant risk factor. [[Silicosis]] increases the risk about 30-fold.<ref name=table3>{{cite journal |title=Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society |journal=MMWR. Recommendations and Reports |volume=49 |issue=RR–6 |pages=1–51 |date=June 2000 |pmid=10881762 |url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr4906a1.htm#tab3 |author1=ATS/CDC Statement Committee on Latent Tuberculosis Infection |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20041217172736/http://www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/rr4906a1.htm#tab3 |archivedate=17 December 2004 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> Those who smoke [[cigarette]]s have nearly twice the risk of TB compared to nonsmokers.<ref>{{cite journal|last=van Zyl Smit|first=RN|author2=Pai, M |author3=Yew, WW |author4=Leung, CC |author5=Zumla, A |author6=Bateman, ED |author7=Dheda, K |title=Global lung health: the colliding epidemics of tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, HIV and COPD| journal=European Respiratory Journal |date=January 2010|volume=35|issue=1|pages=27–33|pmid=20044459|quote=These analyses indicate that smokers are almost twice as likely to be infected with TB and to progress to active disease (RR of about 1.5 for latent TB infection (LTBI) and RR of ∼2.0 for TB disease). Smokers are also twice as likely to die from TB (RR of about 2.0 for TB mortality), but data are difficult to interpret because of heterogeneity in the results across studies.|doi=10.1183/09031936.00072909}}</ref> |

||

Other disease states can also increase the risk of developing tuberculosis. These include [[alcoholism]]<ref name=Lancet11/> and [[diabetes mellitus]] (three-fold increase).<ref>{{cite journal|last=Restrepo|first=BI|title=Convergence of the tuberculosis and diabetes epidemics: renewal of old acquaintances|journal=Clinical Infectious Diseases |date=15 August 2007|volume=45|issue=4|pages=436–8|pmid=17638190|doi=10.1086/519939|pmc=2900315}}</ref> |

Other disease states can also increase the risk of developing tuberculosis. These include [[alcoholism]]<ref name=Lancet11/> and [[diabetes mellitus]] (three-fold increase).<ref>{{cite journal|last=Restrepo|first=BI|title=Convergence of the tuberculosis and diabetes epidemics: renewal of old acquaintances|journal=Clinical Infectious Diseases |date=15 August 2007|volume=45|issue=4|pages=436–8|pmid=17638190|doi=10.1086/519939|pmc=2900315}}</ref> |

||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

When people with active pulmonary TB cough, sneeze, speak, sing, or spit, they expel infectious [[aerosol]] droplets 0.5 to 5.0 [[µm]] in diameter. A single sneeze can release up to 40,000 droplets.<ref name=Cole_1998>{{cite journal |vauthors=Cole E, Cook C |title=Characterization of infectious aerosols in health care facilities: an aid to effective engineering controls and preventive strategies |journal=Am J Infect Control |volume=26 |issue=4 |pages=453–64 |year=1998 |pmid=9721404|doi = 10.1016/S0196-6553(98)70046-X}}</ref> Each one of these droplets may transmit the disease, since the infectious dose of tuberculosis is very small (the inhalation of fewer than 10 bacteria may cause an infection).<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Nicas M, Nazaroff WW, Hubbard A |title=Toward understanding the risk of secondary airborne infection: emission of respirable pathogens |journal=J Occup Environ Hyg |volume=2 |issue=3 |pages=143–54 |year=2005 |pmid=15764538|doi = 10.1080/15459620590918466}}</ref> |

When people with active pulmonary TB cough, sneeze, speak, sing, or spit, they expel infectious [[aerosol]] droplets 0.5 to 5.0 [[µm]] in diameter. A single sneeze can release up to 40,000 droplets.<ref name=Cole_1998>{{cite journal |vauthors=Cole E, Cook C |title=Characterization of infectious aerosols in health care facilities: an aid to effective engineering controls and preventive strategies |journal=Am J Infect Control |volume=26 |issue=4 |pages=453–64 |year=1998 |pmid=9721404|doi = 10.1016/S0196-6553(98)70046-X}}</ref> Each one of these droplets may transmit the disease, since the infectious dose of tuberculosis is very small (the inhalation of fewer than 10 bacteria may cause an infection).<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Nicas M, Nazaroff WW, Hubbard A |title=Toward understanding the risk of secondary airborne infection: emission of respirable pathogens |journal=J Occup Environ Hyg |volume=2 |issue=3 |pages=143–54 |year=2005 |pmid=15764538|doi = 10.1080/15459620590918466}}</ref> |

||

People with prolonged, frequent, or close contact with people with TB are at particularly high risk of becoming infected, with an estimated 22% infection rate.<ref name=Ahmed_2011>{{cite journal |vauthors=Ahmed N, Hasnain S |title=Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in India: Moving forward with a systems biology approach |journal=Tuberculosis |volume=91 |issue=5 |pages=407–3 |year=2011|pmid = 21514230|doi = 10.1016/j.tube.2011.03.006}}</ref> A person with active but untreated tuberculosis may infect 10–15 (or more) other people per year.<ref name="WHO2012data"/> Transmission should occur from only people with active TB – those with latent infection are not thought to be contagious.<ref name=Robbins/> The probability of transmission from one person to another depends upon several factors, including the number of infectious droplets expelled by the carrier, the effectiveness of ventilation, the duration of exposure, the [[virulence]] of the ''M. tuberculosis'' [[strain (biology)|strain]], the level of immunity in the uninfected person, and others.<ref name=CDCcourse>{{cite web|publisher=[[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination|url=http://www.cdc.gov/tb/education/corecurr/pdf/corecurr_all.pdf|title=Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis: What the Clinician Should Know|page=24|edition=5th|year=2011}}</ref> The cascade of person-to-person spread can be circumvented by segregating those with active ("overt") TB and putting them on anti-TB drug regimens. After about two weeks of effective treatment, subjects with [[Antibiotic resistance|nonresistant]] active infections generally do not remain contagious to others.<ref name="Ahmed_2011"/> If someone does become infected, it typically takes three to four weeks before the newly infected person becomes infectious enough to transmit the disease to others.<ref>{{cite web |

People with prolonged, frequent, or close contact with people with TB are at particularly high risk of becoming infected, with an estimated 22% infection rate.<ref name=Ahmed_2011>{{cite journal |vauthors=Ahmed N, Hasnain S |title=Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in India: Moving forward with a systems biology approach |journal=Tuberculosis |volume=91 |issue=5 |pages=407–3 |year=2011|pmid = 21514230|doi = 10.1016/j.tube.2011.03.006}}</ref> A person with active but untreated tuberculosis may infect 10–15 (or more) other people per year.<ref name="WHO2012data"/> Transmission should occur from only people with active TB – those with latent infection are not thought to be contagious.<ref name=Robbins/> The probability of transmission from one person to another depends upon several factors, including the number of infectious droplets expelled by the carrier, the effectiveness of ventilation, the duration of exposure, the [[virulence]] of the ''M. tuberculosis'' [[strain (biology)|strain]], the level of immunity in the uninfected person, and others.<ref name=CDCcourse>{{cite web|publisher=[[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination|url=http://www.cdc.gov/tb/education/corecurr/pdf/corecurr_all.pdf|title=Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis: What the Clinician Should Know|page=24|edition=5th|year=2011|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120519141115/http://www.cdc.gov/tb/education/corecurr/pdf/corecurr_all.pdf|archivedate=19 May 2012|df=dmy-all}}</ref> The cascade of person-to-person spread can be circumvented by segregating those with active ("overt") TB and putting them on anti-TB drug regimens. After about two weeks of effective treatment, subjects with [[Antibiotic resistance|nonresistant]] active infections generally do not remain contagious to others.<ref name="Ahmed_2011"/> If someone does become infected, it typically takes three to four weeks before the newly infected person becomes infectious enough to transmit the disease to others.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/tuberculosis/DS00372/DSECTION=3|title=Causes of Tuberculosis|accessdate=19 October 2007|date=21 December 2006|publisher=[[Mayo Clinic]]|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20071018051807/http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/tuberculosis/DS00372/DSECTION%3D3|archivedate=18 October 2007|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

||

===Pathogenesis=== |

===Pathogenesis=== |

||

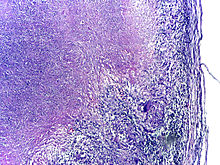

[[File:Tuberculous epididymitis Low Power.jpg|thumb|Microscopy of tuberculous epididymitis. [[H&E]] stain]] |

[[File:Tuberculous epididymitis Low Power.jpg|thumb|Microscopy of tuberculous epididymitis. [[H&E]] stain]] |

||

About 90% of those infected with ''M. tuberculosis'' have [[asymptomatic]], latent TB infections (sometimes called LTBI),<ref name=Book90>{{cite book|last=Skolnik|first=Richard|title=Global health 101|year=2011|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|location=Burlington, MA|isbn=978-0-7637-9751-5|pages=253|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sBQRpj4uWmYC&pg=PA253|edition=2nd}}</ref> with only a 10% lifetime chance that the latent infection will progress to overt, active tuberculous disease.<ref name=Arch2009>{{cite book|last=editors|first=Arch G. Mainous III, Claire Pomeroy,|title=Management of antimicrobials in infectious diseases: impact of antibiotic resistance.|year=2009|publisher=Humana Press|location=Totowa, N.J.|isbn=978-1-60327-238-4|pages=74|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hwVFAPLYznsC&pg=PA74|edition=2nd rev.}}</ref> In those with HIV, the risk of developing active TB increases to nearly 10% a year.<ref name=Arch2009/> If effective treatment is not given, the death rate for active TB cases is up to 66%.<ref name=WHO2012data>{{cite web|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/index.html|title=Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104|publisher=[[World Health Organization]]|date=November 2010|accessdate=26 July 2011}}</ref> |

About 90% of those infected with ''M. tuberculosis'' have [[asymptomatic]], latent TB infections (sometimes called LTBI),<ref name=Book90>{{cite book|last=Skolnik|first=Richard|title=Global health 101|year=2011|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning|location=Burlington, MA|isbn=978-0-7637-9751-5|pages=253|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sBQRpj4uWmYC&pg=PA253|edition=2nd|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906174239/https://books.google.com/books?id=sBQRpj4uWmYC&pg=PA253|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> with only a 10% lifetime chance that the latent infection will progress to overt, active tuberculous disease.<ref name=Arch2009>{{cite book|last=editors|first=Arch G. Mainous III, Claire Pomeroy,|title=Management of antimicrobials in infectious diseases: impact of antibiotic resistance.|year=2009|publisher=Humana Press|location=Totowa, N.J.|isbn=978-1-60327-238-4|pages=74|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hwVFAPLYznsC&pg=PA74|edition=2nd rev.|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906224212/https://books.google.com/books?id=hwVFAPLYznsC&pg=PA74|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In those with HIV, the risk of developing active TB increases to nearly 10% a year.<ref name=Arch2009/> If effective treatment is not given, the death rate for active TB cases is up to 66%.<ref name=WHO2012data>{{cite web|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/index.html|title=Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104|publisher=[[World Health Organization]]|date=November 2010|accessdate=26 July 2011|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20061004013508/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/index.html|archivedate=4 October 2006|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

||

TB infection begins when the mycobacteria reach the [[Pulmonary alveolus|pulmonary alveoli]], where they invade and replicate within [[endosomes]] of alveolar [[macrophages]].<ref name=Robbins/><ref name=Houben>{{cite journal |vauthors=Houben E, Nguyen L, Pieters J | title=Interaction of pathogenic mycobacteria with the host immune system | journal=Curr Opin Microbiol | volume=9 | issue=1 | pages=76–85 | year=2006 | pmid=16406837 | doi=10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.014 }}</ref> Macrophages identify the bacterium as foreign and attempt to eliminate it by [[phagocytosis]]. During this process, the bacterium is enveloped by the macrophage and stored temporarily in a membrane-bound vesicle called a phagosome. The phagosome then combines with a lysosome to create a phagolysosome. In the phagolysosome, the cell attempts to use [[reactive oxygen species]] and acid to kill the bacterium. However, ''M. tuberculosis'' has a thick, waxy [[mycolic acid]] capsule that protects it from these toxic substances. ''M. tuberculosis'' is able to reproduce inside the macrophage and will eventually kill the immune cell. |

TB infection begins when the mycobacteria reach the [[Pulmonary alveolus|pulmonary alveoli]], where they invade and replicate within [[endosomes]] of alveolar [[macrophages]].<ref name=Robbins/><ref name=Houben>{{cite journal |vauthors=Houben E, Nguyen L, Pieters J | title=Interaction of pathogenic mycobacteria with the host immune system | journal=Curr Opin Microbiol | volume=9 | issue=1 | pages=76–85 | year=2006 | pmid=16406837 | doi=10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.014 }}</ref> Macrophages identify the bacterium as foreign and attempt to eliminate it by [[phagocytosis]]. During this process, the bacterium is enveloped by the macrophage and stored temporarily in a membrane-bound vesicle called a phagosome. The phagosome then combines with a lysosome to create a phagolysosome. In the phagolysosome, the cell attempts to use [[reactive oxygen species]] and acid to kill the bacterium. However, ''M. tuberculosis'' has a thick, waxy [[mycolic acid]] capsule that protects it from these toxic substances. ''M. tuberculosis'' is able to reproduce inside the macrophage and will eventually kill the immune cell. |

||

The primary site of infection in the lungs, known as the "[[Ghon focus]]", is generally located in either the upper part of the lower lobe, or the lower part of the [[lung|upper lobe]].<ref name=Robbins/> Tuberculosis of the lungs may also occur via infection from the blood stream. This is known as a [[Simon focus]] and is typically found in the top of the lung.<ref>{{cite book|last=Khan|title=Essence Of Paediatrics|year=2011|publisher=Elsevier India|isbn=978-81-312-2804-3|pages=401|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gERCc6KTxwoC&pg=PA401}}</ref> This hematogenous transmission can also spread infection to more distant sites, such as peripheral lymph nodes, the kidneys, the brain, and the bones.<ref name=Robbins/><ref name=Herrmann_2005>{{cite journal |vauthors=Herrmann J, Lagrange P |title=Dendritic cells and ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'': which is the Trojan horse? |journal=Pathol Biol (Paris) |volume=53 |issue=1 |pages=35–40 |year=2005|pmid = 15620608 |doi=10.1016/j.patbio.2004.01.004}}</ref> All parts of the body can be affected by the disease, though for unknown reasons it rarely affects the [[heart]], [[skeletal muscle]]s, [[pancreas]], or [[thyroid]].<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Agarwal R, Malhotra P, Awasthi A, Kakkar N, Gupta D |pmc=1090580 |title=Tuberculous dilated cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized entity? |journal=BMC Infect Dis |volume=5 |issue=1 |page=29 |year=2005 |pmid=15857515 |doi=10.1186/1471-2334-5-29}}</ref> |

The primary site of infection in the lungs, known as the "[[Ghon focus]]", is generally located in either the upper part of the lower lobe, or the lower part of the [[lung|upper lobe]].<ref name=Robbins/> Tuberculosis of the lungs may also occur via infection from the blood stream. This is known as a [[Simon focus]] and is typically found in the top of the lung.<ref>{{cite book|last=Khan|title=Essence Of Paediatrics|year=2011|publisher=Elsevier India|isbn=978-81-312-2804-3|pages=401|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gERCc6KTxwoC&pg=PA401|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906193259/https://books.google.com/books?id=gERCc6KTxwoC&pg=PA401|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> This hematogenous transmission can also spread infection to more distant sites, such as peripheral lymph nodes, the kidneys, the brain, and the bones.<ref name=Robbins/><ref name=Herrmann_2005>{{cite journal |vauthors=Herrmann J, Lagrange P |title=Dendritic cells and ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'': which is the Trojan horse? |journal=Pathol Biol (Paris) |volume=53 |issue=1 |pages=35–40 |year=2005|pmid = 15620608 |doi=10.1016/j.patbio.2004.01.004}}</ref> All parts of the body can be affected by the disease, though for unknown reasons it rarely affects the [[heart]], [[skeletal muscle]]s, [[pancreas]], or [[thyroid]].<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Agarwal R, Malhotra P, Awasthi A, Kakkar N, Gupta D |pmc=1090580 |title=Tuberculous dilated cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized entity? |journal=BMC Infect Dis |volume=5 |issue=1 |page=29 |year=2005 |pmid=15857515 |doi=10.1186/1471-2334-5-29}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Carswell-Tubercle.jpg|thumb|left|upright=90%|[[Robert Carswell (pathologist)|Robert Carswell]]'s illustration of tubercle<ref name="GoodCooper1835">{{cite book|author1=John Mason Good|author2=Samuel Cooper|author3=Augustus Sidney Doane|title=The Study of Medicine|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K906AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA32|year=1835|publisher=Harper|page=32}}</ref>]] |

[[File:Carswell-Tubercle.jpg|thumb|left|upright=90%|[[Robert Carswell (pathologist)|Robert Carswell]]'s illustration of tubercle<ref name="GoodCooper1835">{{cite book|author1=John Mason Good|author2=Samuel Cooper|author3=Augustus Sidney Doane|title=The Study of Medicine|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K906AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA32|year=1835|publisher=Harper|page=32|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160810194616/https://books.google.com/books?id=K906AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA32|archivedate=10 August 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref>]] |

||

Tuberculosis is classified as one of the [[granuloma]]tous inflammatory diseases. [[Macrophage]]s, [[T cell|T lymphocytes]], [[B cell|B lymphocytes]], and [[fibroblast]]s <!-- are among the cells that --> aggregate to form [[granuloma]]s, with [[lymphocytes]] surrounding the infected macrophages. When other macrophages attack the infected macrophage, they fuse together to form a giant multinucleated cell in the alveolar lumen. The granuloma may prevent dissemination of the mycobacteria and provide a local environment for interaction of cells of the immune system.<ref name=Grosset /> However, more recent evidence suggests that the bacteria use the granulomas to avoid destruction by the host's immune system. Macrophages and [[dendritic cell]]s in the granulomas are unable to present antigen to lymphocytes; thus the immune response is suppressed.<ref>{{cite journal | author=Bozzano F | title=Immunology of tuberculosis | journal=Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis | volume=6 | issue=1 | page=e2014027 | year=2014 | pmid=24804000 | doi=10.4084/MJHID.2014.027 | pmc=4010607 }}</ref> Bacteria inside the granuloma can become dormant, resulting in latent infection. Another feature of the granulomas is the development of abnormal cell death ([[necrosis]]) in the center of [[Tubercle (anatomy)|tubercles]]. To the naked eye, this has the texture of soft, white cheese and is termed [[caseous necrosis]].<ref name=Grosset>{{cite journal |author=Grosset J |title=Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Extracellular Compartment: an Underestimated Adversary |journal=Antimicrob Agents Chemother |volume=47 |issue=3 |pages=833–6 |year=2003|pmid = 12604509|doi = 10.1128/AAC.47.3.833-836.2003 |pmc=149338}}</ref> |

Tuberculosis is classified as one of the [[granuloma]]tous inflammatory diseases. [[Macrophage]]s, [[T cell|T lymphocytes]], [[B cell|B lymphocytes]], and [[fibroblast]]s <!-- are among the cells that --> aggregate to form [[granuloma]]s, with [[lymphocytes]] surrounding the infected macrophages. When other macrophages attack the infected macrophage, they fuse together to form a giant multinucleated cell in the alveolar lumen. The granuloma may prevent dissemination of the mycobacteria and provide a local environment for interaction of cells of the immune system.<ref name=Grosset /> However, more recent evidence suggests that the bacteria use the granulomas to avoid destruction by the host's immune system. Macrophages and [[dendritic cell]]s in the granulomas are unable to present antigen to lymphocytes; thus the immune response is suppressed.<ref>{{cite journal | author=Bozzano F | title=Immunology of tuberculosis | journal=Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis | volume=6 | issue=1 | page=e2014027 | year=2014 | pmid=24804000 | doi=10.4084/MJHID.2014.027 | pmc=4010607 }}</ref> Bacteria inside the granuloma can become dormant, resulting in latent infection. Another feature of the granulomas is the development of abnormal cell death ([[necrosis]]) in the center of [[Tubercle (anatomy)|tubercles]]. To the naked eye, this has the texture of soft, white cheese and is termed [[caseous necrosis]].<ref name=Grosset>{{cite journal |author=Grosset J |title=Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Extracellular Compartment: an Underestimated Adversary |journal=Antimicrob Agents Chemother |volume=47 |issue=3 |pages=833–6 |year=2003|pmid = 12604509|doi = 10.1128/AAC.47.3.833-836.2003 |pmc=149338}}</ref> |

||

If TB bacteria gain entry to the blood stream from an area of damaged tissue, they can spread throughout the body and set up many foci of infection, all appearing as tiny, white tubercles in the tissues.<ref>{{cite book|last=Crowley|first=Leonard V.|title=An introduction to human disease: pathology and pathophysiology correlations|year=2010|publisher=Jones and Bartlett|location=Sudbury, Mass.|isbn=978-0-7637-6591-0|pages=374|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TEiuWP4z_QIC&pg=PA374|edition=8th}}</ref> This severe form of TB disease, most common in young children and those with HIV, is called miliary tuberculosis.<ref>{{cite book|last=Anthony|first=Harries|title=TB/HIV a Clinical Manual.|year=2005|publisher=World Health Organization|location=Geneva|isbn=978-92-4-154634-8|pages=75|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8dfhwKaCSxkC&pg=PA75|edition=2nd }}</ref> People with this disseminated TB have a high fatality rate even with treatment (about 30%).<ref name=Gho2008>{{cite book|last=Ghosh|first=editors-in-chief, Thomas M. Habermann, Amit K.|title=Mayo Clinic internal medicine: concise textbook|year=2008|publisher=Mayo Clinic Scientific Press|location=Rochester, MN|isbn=978-1-4200-6749-1|pages=789|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YJtodBwNxokC&pg=PA789}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Jacob|first=JT |author2=Mehta, AK |author3=Leonard, MK|title=Acute forms of tuberculosis in adults|journal=The American Journal of Medicine|date=January 2009|volume=122|issue=1|pages=12–7|pmid=19114163|doi=10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.018}}</ref> |

If TB bacteria gain entry to the blood stream from an area of damaged tissue, they can spread throughout the body and set up many foci of infection, all appearing as tiny, white tubercles in the tissues.<ref>{{cite book|last=Crowley|first=Leonard V.|title=An introduction to human disease: pathology and pathophysiology correlations|year=2010|publisher=Jones and Bartlett|location=Sudbury, Mass.|isbn=978-0-7637-6591-0|pages=374|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TEiuWP4z_QIC&pg=PA374|edition=8th|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906193726/https://books.google.com/books?id=TEiuWP4z_QIC&pg=PA374|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> This severe form of TB disease, most common in young children and those with HIV, is called miliary tuberculosis.<ref>{{cite book|last=Anthony|first=Harries|title=TB/HIV a Clinical Manual.|year=2005|publisher=World Health Organization|location=Geneva|isbn=978-92-4-154634-8|pages=75|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8dfhwKaCSxkC&pg=PA75|edition=2nd|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906195514/https://books.google.com/books?id=8dfhwKaCSxkC&pg=PA75|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> People with this disseminated TB have a high fatality rate even with treatment (about 30%).<ref name=Gho2008>{{cite book|last=Ghosh|first=editors-in-chief, Thomas M. Habermann, Amit K.|title=Mayo Clinic internal medicine: concise textbook|year=2008|publisher=Mayo Clinic Scientific Press|location=Rochester, MN|isbn=978-1-4200-6749-1|pages=789|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YJtodBwNxokC&pg=PA789|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906190055/https://books.google.com/books?id=YJtodBwNxokC&pg=PA789|archivedate=6 September 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Jacob|first=JT |author2=Mehta, AK |author3=Leonard, MK|title=Acute forms of tuberculosis in adults|journal=The American Journal of Medicine|date=January 2009|volume=122|issue=1|pages=12–7|pmid=19114163|doi=10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.018}}</ref> |

||

In many people, the infection waxes and wanes. Tissue destruction and necrosis are often balanced by healing and [[fibrosis]].<ref name=Grosset/> Affected tissue is replaced by scarring and cavities filled with caseous necrotic material. During active disease, some of these cavities are joined to the air passages [[bronchi]] and this material can be coughed up. It contains living bacteria, so can spread the infection. Treatment with appropriate [[antibiotic]]s kills bacteria and allows healing to take place. Upon cure, affected areas are eventually replaced by scar tissue.<ref name=Grosset/> |

In many people, the infection waxes and wanes. Tissue destruction and necrosis are often balanced by healing and [[fibrosis]].<ref name=Grosset/> Affected tissue is replaced by scarring and cavities filled with caseous necrotic material. During active disease, some of these cavities are joined to the air passages [[bronchi]] and this material can be coughed up. It contains living bacteria, so can spread the infection. Treatment with appropriate [[antibiotic]]s kills bacteria and allows healing to take place. Upon cure, affected areas are eventually replaced by scar tissue.<ref name=Grosset/> |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||