Battle of Verdun

| Battle of Verdun | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

Map of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 50 divisions | 75 divisions (in sequence) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

336,000–355,000 casualties

|

379,000–400,000 casualties

| ||||||

Verdun (before 1970, Verdun-sur-Meuse), a city in the Meuse department in Grand Est in northeastern France | |||||||

The Battle of Verdun (Template:Lang-fr [bataj də vɛʁdœ̃]; Template:Lang-de [ʃlaxt ʔʊm ˈvɛɐ̯dœ̃]) was fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front in France. The battle was the longest of the First World War and took place on the hills north of Verdun-sur-Meuse. The German 5th Army attacked the defences of the Fortified Region of Verdun (RFV, Région Fortifiée de Verdun) and those of the French Second Army on the right (east) bank of the Meuse. Using the experience of the Second Battle of Champagne in 1915, the Germans planned to capture the Meuse Heights, an excellent defensive position, with good observation for artillery-fire on Verdun. The Germans hoped that the French would commit their strategic reserve to recapture the position and suffer catastrophic losses at little cost to the German infantry.

Poor weather delayed the beginning of the attack until 21 February but the Germans captured Fort Douaumont in the first three days. The advance then slowed for several days, despite inflicting many French casualties. By 6 March, 20+1⁄2 French divisions were in the RFV and a more extensive defence in depth had been organised. Philippe Pétain ordered there to be no retreat and that German attacks were to be counter-attacked, despite this exposing French infantry to the German artillery. By 29 March, French guns on the west bank had begun a constant bombardment of Germans on the east bank, causing many infantry casualties. The German offensive was extended to the west bank of the Meuse to gain observation and eliminate the French artillery firing over the river but the attacks failed to reach their objectives.

In early May, the Germans changed tactics again and made local attacks and counter-attacks; the French recaptured part of Fort Douaumont but then the Germans ejected them and took many prisoners. The Germans tried alternating their attacks on either side of the Meuse and in June captured Fort Vaux. The Germans advanced towards the last geographical objectives of the original plan, at Fleury-devant-Douaumont and Fort Souville, driving a salient into the French defences. Fleury was captured and the Germans came within 4 km (2 mi) of the Verdun citadel but in July the offensive was cut back to provide troops, artillery and ammunition for the Battle of the Somme, leading to a similar transfer of the French Tenth Army to the Somme front. From 23 June to 17 August, Fleury changed hands sixteen times and a German attack on Fort Souville failed. The offensive was reduced further but to keep French troops away from the Somme, ruses were used to disguise the change.

In September and December, French counter-offensives recaptured much ground on the east bank and recovered Fort Douaumont and Fort Vaux. The battle lasted for 302 days, the longest and one of the most costly in human history. In 2000, Hannes Heer and Klaus Naumann calculated that the French suffered 377,231 casualties and the Germans 337,000, a total of 714,231 and an average of 70,000 a month. In 2014, William Philpott wrote of 976,000 casualties in 1916 and 1,250,000 in the vicinity of Verdun. In France, the battle came to symbolise the determination of the French Army and the destructiveness of the war.

Background

Strategic developments

After the German invasion of France had been halted at the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914, the war of movement ended at the Battle of the Yser and the First Battle of Ypres. The Germans built field fortifications to hold the ground captured in 1914 and the French began siege warfare to break through the German defences and recover the lost territory. In late 1914 and in 1915, offensives on the Western Front had failed to gain much ground and been extremely costly in casualties.[a] According to his memoirs written after the war, the Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, believed that although victory might no longer be achieved by a decisive battle, the French army could still be defeated if it suffered a sufficient number of casualties.[1] Falkenhayn offered five corps from the strategic reserve for an offensive at Verdun at the beginning of February 1916 but only for an attack on the east bank of the Meuse. Falkenhayn considered it unlikely the French would be complacent about Verdun; he thought that they might send all their reserves there and begin a counter-offensive elsewhere or fight to hold Verdun while the British launched a relief offensive. After the war, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Gerhard Tappen, the Operations Officer at Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, General Headquarters), wrote that Falkenhayn believed the last possibility was most likely.[2]

By seizing or threatening to capture Verdun, the Germans anticipated that the French would send all their reserves, which would then have to attack secure German defensive positions supported by a powerful artillery reserve. In the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive (1 May to 19 September 1915), the German and Austro-Hungarian Armies attacked Russian defences frontally, after pulverising them with large amounts of heavy artillery. During the Second Battle of Champagne (Herbstschlacht [autumn battle]) 25 September to 6 November 1915, the French suffered "extraordinary casualties" from the German heavy artillery, which Falkenhayn considered offered a way out of the dilemma of material inferiority and the growing strength of the Allies. In the north, a British relief offensive would wear down British reserves, to no decisive effect but create the conditions for a German counter-offensive near Arras.[3]

Hints about Falkenhayn's thinking were picked up by Dutch military intelligence and passed on to the British in December. The German strategy was to create a favourable operational situation without a mass attack, which had been costly and ineffective when tried by the Franco-British, Falkenhayn intended to rely on the power of heavy artillery to inflict mass casualties. A limited offensive at Verdun would lead to the destruction of the French strategic reserve in fruitless counter-attacks and the defeat of British reserves during a hopeless relief offensive, leading to the French accepting a separate peace. If the French refused to negotiate, the second phase of the strategy would follow, in which the German armies would attack terminally weakened Franco-British armies, mop up the remains of the French armies and expel the British from Europe. To fulfil this strategy, Falkenhayn needed to hold back enough of the strategic reserve to defeat the Anglo-French relief offensives and then conduct a counter-offensive, which limited the number of divisions which could be sent to the 5th Army at Verdun for Unternehmen Gericht (Operation Judgement).[4]

The Fortified Region of Verdun (RFV) lay in a salient formed during the German invasion of 1914. General Joseph Joffre, the Commander-in-Chief of the French Army, had concluded from the swift capture of the Belgian fortresses at the Battle of Liège and at the Siege of Namur in 1914 that fortifications had been made obsolete by German super-heavy siege artillery. In a directive of the General Staff of 5 August 1915, the RFV was to be stripped of 54 artillery batteries and 128,000 rounds of ammunition. Plans to demolish forts Douaumont and Vaux to deny them to the Germans were made and 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) of explosives had been placed in Douaumont by the time of the German offensive on 21 February. The 18 large forts and other batteries around Verdun were left with fewer than 300 guns and a small reserve of ammunition, while their garrisons had been reduced to small maintenance crews.[5] The railway line from the south into Verdun had been cut during the Battle of Flirey in 1914, with the loss of Saint-Mihiel; the line west from Verdun to Paris was cut at Aubréville in mid-July 1915 by the German 3rd Army, which had attacked southwards through the Argonne Forest since the new year.[6]

Région Fortifiée de Verdun

For centuries, Verdun, on the Meuse river, had played an important role in the defence of the French hinterland. Attila the Hun failed to seize the town in the fifth century and when the empire of Charlemagne was divided under the Treaty of Verdun (843), the town became part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 awarded Verdun to France. At the heart of the city was a citadel built by Vauban in the 17th century.[7] A double ring of 28 forts and smaller works (ouvrages) had been built around Verdun on commanding ground, at least 150 m (490 ft) above the river valley, 2.5–8 km (1.6–5.0 mi) from the citadel. A programme had been devised by Séré de Rivières in the 1870s to build two lines of fortresses from Belfort to Épinal and from Verdun to Toul as defensive screens and to enclose towns intended to be the bases for counter-attacks.[8][b] Many of the Verdun forts had been modernised and made more resistant to artillery, with a reconstruction programme begun at Douaumont in the 1880s. A sand cushion and thick, steel-reinforced concrete tops up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) thick, buried under 1–4 m (3.3–13.1 ft) of earth, were added. The forts and ouvrages were sited to overlook each other for mutual support and the outer ring had a circumference of 45 km (28 mi). The outer forts had 79 guns in shellproof turrets and more than 200 light guns and machine-guns to protect the ditches around the forts. Six forts had 155 mm guns in retractable turrets and fourteen had retractable twin 75 mm turrets.[10]

In 1903, Douaumont was equipped with a new concrete bunker (Casemate de Bourges), containing two 75 mm field guns to cover the south-western approach and the defensive works along the ridge to Ouvrage de Froideterre. More guns were added from 1903 to 1913 in four retractable steel turrets. The guns could rotate for all-round defence and two smaller versions, at the north-eastern and north-western corners of the fort, housed twin Hotchkiss machine-guns. On the east side of the fort, an armoured turret with a 155 mm short-barrelled gun faced north and north-east and another housed twin 75 mm guns at the north end, to cover the intervals between the neighbouring forts. The fort at Douaumont formed part of a complex of the village, fort, six ouvrages, five shelters, six concrete batteries, an underground infantry shelter, two ammunition depots and several concrete infantry trenches.[11] The Verdun forts had a network of concrete infantry shelters, armoured observation posts, batteries, concrete trenches, command posts and underground shelters between the forts. The artillery comprised c. 1,000 guns, with 250 in reserve; the forts and ouvrages were linked by telephone and telegraph, a narrow-gauge railway system and a road network; on mobilisation, the RFV had a garrison of 66,000 men and rations for six months.[9][c]

Prelude

German preparations

Verdun had been isolated on three sides since 1914 and the mainline Paris–St Menehould–Les Islettes–Clermont-en-Argonne–Aubréville–Verdun railway in the Forest of Argonne was closed in mid-July 1915 by the right flank divisions of the 5th Army (Generalmajor Crown Prince Wilhelm) when it reached the La Morte Fille–Hill 285 ridge after continuous local attacks, rendering the railway unusable.[13] Only a light railway remained to the French to carry bulk supplies; German-controlled mainline railways lay only 24 km (15 mi) to the north of the front line. A corps was moved to the 5th Army to provide labour for the preparation of the offensive. Areas were emptied of French civilians and buildings requisitioned. Thousands of kilometres of telephone cable were laid, a huge amount of ammunition and rations was dumped under cover and hundreds of guns were emplaced and camouflaged. Ten new rail lines with twenty stations were built and vast underground shelters (Stollen) 4.5–14 m (15–46 ft) deep were dug, each to accommodate up to 1,200 infantry.[14]

The III Corps, VII Reserve Corps and XVIII Corps were transferred to the 5th Army, each corps being reinforced by 2,400 experienced troops and 2,000 trained recruits. V Corps was placed behind the front line, ready to advance if necessary when the assault divisions were moving up. XV Corps, with two divisions, was in the 5th Army reserve, ready to advance to mop up as soon as the French defence collapsed.[14] Special arrangements were made to maintain a high rate of artillery fire during the offensive; 33+1⁄2 munitions trains per day were to deliver ammunition sufficient for 2,000,000 rounds to be fired in the first six days and another 2,000,000 shells in the next twelve. Five repair shops were built close to the front to reduce delays for maintenance and factories in Germany were made ready, rapidly to refurbish artillery needing more extensive repairs. A redeployment plan for the artillery was devised to move field guns and mobile heavy artillery forward, under the covering fire of mortars and the super-heavy artillery. A total of 1,201 guns were massed on the Verdun front, two thirds of which were heavy- and super-heavy artillery, which was obtained by stripping the modern German artillery from the rest of the Western Front and substituting for it older types and captured Russian and Belgian guns. The German artillery could fire into the Verdun salient from three directions yet remain dispersed around the edges.[15]

German plan

The 5th Army divided the attack front into areas, A occupied by the VII Reserve Corps, B by the XVIII Corps, C by the III Corps and D on the Woëvre plain by the XV Corps. The preliminary artillery bombardment was to begin in the morning of 12 February. At 5:00 p.m., the infantry in areas A to C would advance in open order, supported by grenade and flame-thrower detachments.[16] Wherever possible, the French advanced trenches were to be occupied and the second position reconnoitred for the artillery to bombard on the second day. Great emphasis was placed on limiting German infantry casualties by sending them to follow up destructive bombardments by the artillery, which was to carry the burden of the offensive in a series of large "attacks with limited objectives", to maintain a relentless pressure on the French. The initial objectives were the Meuse Heights, on a line from Froide Terre to Fort Souville and Fort Tavannes, which would provide a secure defensive position from which to repel French counter-attacks. "Relentless pressure" was a term added by the 5th Army staff and created ambiguity about the purpose of the offensive. Falkenhayn wanted land to be captured from which artillery could dominate the battlefield and the 5th Army wanted a quick capture of Verdun. The confusion caused by the ambiguity was left to the corps headquarters to sort out.[17]

Control of the artillery was centralised by an Order for the Activities of the Artillery and Mortars, which stipulated that the corps Generals of Foot Artillery were responsible for local target selection, while co-ordination of flanking fire by neighbouring corps and the fire of certain batteries, was reserved to the 5th Army headquarters. French fortifications were to be engaged by the heaviest howitzers and enfilade fire. The heavy artillery was to maintain long-range bombardment of French supply routes and assembly areas; counter-battery fire was reserved for specialist batteries firing gas shells. Co-operation between the artillery and infantry was stressed, with accuracy of the artillery being given priority over rate of fire. The opening bombardment was to build up slowly and Trommelfeuer (a rate of fire so rapid that the sound of shell-explosions merged into a rumble) would not begin until the last hour. As the infantry advanced, the artillery would increase the range of the bombardment to destroy the French second position. Artillery observers were to advance with the infantry and communicate with the guns by field telephones, flares and coloured balloons. When the offensive began, the French were to be bombarded continuously, with harassing fire being maintained at night.[18]

French preparations

In 1915, 237 guns and 647 long tons (657 t) of ammunition in the forts of the RFV had been removed, leaving only the heavy guns in retractable turrets. The conversion of the RFV to a conventional linear defence, with trenches and barbed wire began but proceeded slowly, after resources were sent west from Verdun for the Second Battle of Champagne (25 September to 6 November 1915). In October 1915, building began on trench lines known as the first, second and third positions and in January 1916, an inspection by General Noël de Castelnau, Chief of Staff at French General Headquarters (GQG), reported that the new defences were satisfactory, except for small deficiencies in three areas.[19] The fortress garrisons had been reduced to small maintenance crews and some of the forts had been readied for demolition. The maintenance garrisons were responsible to the central military bureaucracy in Paris and when the XXX Corps commander, Major-General Paul Chrétien, attempted to inspect Fort Douaumont in January 1916, he was refused entry.[20]

Douaumont was the largest fort in the RFV and by February 1916, the only artillery left in the fort were the 75 mm and 155 mm turret guns and light guns covering the ditch. The fort was used as a barracks by 68 technicians under the command of Warrant Officer Chenot, the Gardien de Batterie. One of the rotating 155 mm (6.1 in) turrets was partially manned and the other was left empty.[20] The Hotchkiss machine-guns were stored in boxes and four 75 mm guns in the casemates had already been removed. The drawbridge had been jammed in the down position by a German shell and had not been repaired. The coffres (wall bunkers) with Hotchkiss revolver-cannons protecting the moats, were unmanned and over 5,000 kg (11,023 lb; 5 long tons) of explosives had been placed in the fort to demolish it.[5] Colonel Émile Driant was stationed at Verdun and criticised Joffre for removing the artillery guns and infantry from fortresses around Verdun. Joffre did not listen but Colonel Driant received the support of the Minister for War Joseph Gallieni. The formidable Verdun defences were a shell and were now threatened by a German offensive; Driant was to be proved correct by events.

In late January 1916, French intelligence obtained an accurate assessment of German military capacity and intentions at Verdun but Joffre considered that an attack would be a diversion, because of the lack of an obvious strategic objective.[21] By the time of the German offensive, Joffre expected a bigger attack elsewhere but finally yielded to political pressure and ordered the VII Corps to Verdun on 23 January, to hold the north face of the west bank. XXX Corps held the salient east of the Meuse to the north and north-east and II Corps held the eastern face of the Meuse Heights; Herr had 8+1⁄2 divisions in the front line, with 2+1⁄2 divisions in close reserve. Groupe d'armées du centre (GAC, General De Langle de Cary) had the I and XX corps with two divisions each in reserve, plus most of the 19th Division; Joffre had 25 divisions in the French strategic reserve.[22] French artillery reinforcements had brought the total at Verdun to 388 field guns and 244 heavy guns, against 1,201 German guns, two thirds of which were heavy and super heavy, including 14 in (356 mm) and 202 mortars, some being 16 in (406 mm). Eight specialist flame-thrower companies were also sent to the 5th Army.[23]

Castelnau met De Langle de Cary on 25 February, who doubted the east bank could be held. Castelnau disagreed and ordered General Frédéric-Georges Herr the corps commander, to hold the right (east) bank of the Meuse at all costs. Herr sent a division from the west bank and ordered XXX Corps to hold a line from Bras to Douaumont, Vaux and Eix. Pétain took over command of the defence of the RFV at 11:00 p.m., with Colonel Maurice de Barescut as chief of staff and Colonel Bernard Serrigny as head of operations, only to hear that Fort Douaumont had fallen. Pétain ordered the remaining Verdun forts to be re-garrisoned.[24] Four groups were established, under the command of Generals Adolphe Guillaumat, Balfourier and Denis Duchêne on the right bank and Georges de Bazelaire on the left bank. A "line of resistance" was established on the east bank from Souville to Thiaumont, around Fort Douaumont to Fort Vaux, Moulainville and along the ridge of the Woëvre. On the west bank, the line ran from Cumières to Mort Homme, Côte 304 and Avocourt. A "line of panic" was planned in secret as a final line of defence north of Verdun, through forts Belleville, St. Michel and Moulainville.[25] I Corps and XX Corps arrived from 24 to 26 February, increasing the number of divisions in the RFV to 14+1⁄2. By 6 March, the arrival of the XIII, XXI, XIV and XXXIII corps had increased the total to 20+1⁄2 divisions.[26]

Battle

First phase, 21 February – 1 March

21–26 February

Unternehmen Gericht (Operation Judgement) was due to begin on 12 February but fog, heavy rain and high winds delayed the offensive until 7:15 a.m. on 21 February, when a 10-hour artillery bombardment by 808 guns began. The German artillery fired c. 1,000,000 shells along a front about 30 km (19 mi) long by 5 km (3.1 mi) wide.[27] The main concentration of fire was on the right (east) bank of the Meuse river. Twenty-six super-heavy, long-range guns, up to 420 mm (16.5 in), fired on the forts and the city of Verdun; a rumble could be heard 160 km (99 mi) away.[28]

The bombardment was paused at midday, as a ruse to prompt French survivors to reveal themselves, and German artillery-observation aircraft were able to fly over the battlefield unmolested by French aircraft.[28] The III Corps, VII Corps and XVIII Corps attacked at 4:00 p.m.; the Germans used flamethrowers and stormtroopers followed closely with rifles slung, using hand grenades to kill the remaining defenders. This tactic had been developed by Captain Willy Rohr and Sturm-Bataillon Nr. 5 (Rohr), the battalion which conducted the attack.[29] French survivors engaged the attackers, yet the Germans suffered only c. 600 casualties.[30]

By 22 February German troops had advanced 5 km (3.1 mi) and captured Bois des Caures at the edge of the village of Flabas. Two French battalions had held the bois (wood) for two days but were forced back to Samogneux, Beaumont-en-Auge and Ornes. Driant was killed, fighting with the 56th and 59th Bataillons de chasseurs à pied and only 118 of the Chasseurs managed to escape. Poor communications meant that only then did the French High Command realise the seriousness of the attack. The Germans managed to take the village of Haumont but French forces repulsed a German attack on the village of Bois de l'Herbebois. On 23 February, a French counter-attack at Bois des Caures was defeated.[31]

Fighting for Bois de l'Herbebois continued until the Germans outflanked the French defenders from Bois de Wavrille. The German attackers suffered many casualties during their attack on Bois de Fosses and the French held on to Samogneux. German attacks continued on 24 February and the French XXX Corps was forced out of the second line of defence; XX Corps (General Maurice Balfourier) arrived at the last minute and was rushed forward. That evening Castelnau advised Joffre that the Second Army, under General Pétain, should be sent to the RFV. The Germans had captured Beaumont-en-Verdunois, Bois des Fosses and Bois des Caurières and were moving up ravin Hassoule, which led to Fort Douaumont.[31]

At 3:00 p.m. on 25 February, infantry of Brandenburg Regiment 24 advanced with the II and III battalions side-by-side, each formed into two waves composed of two companies each. A delay in the arrival of orders to the regiments on the flanks, led to the III Battalion advancing without support on that flank. The Germans rushed French positions in the woods and on Côte 347, with the support of machine-gun fire from the edge of Bois Hermitage. The German infantry took many prisoners as the French on Côte 347 were outflanked and withdrew to Douaumont village. The German infantry had reached their objectives in under twenty minutes and pursued the French, until fired on by a machine-gun in Douaumont church. Some German troops took cover in woods and a ravine which led to the fort, when German artillery began to bombard the area, the gunners having refused to believe claims sent by field telephone that the German infantry were within a few hundred metres of the fort. Several German parties were forced to advance to find cover from the German shelling and two parties independently made for the fort.[32][d] The Germans did not know that the French garrison was made up of only a small maintenance crew led by a warrant officer, since most of the Verdun forts had been partly disarmed, after the demolition of Belgian forts in 1914, by the German super-heavy Krupp 420 mm mortars.[32]

The German party of c. 100 soldiers tried to signal to the artillery with flares but twilight and falling snow obscured them from view. Some of the party began to cut through the wire around the fort, while French machine-gun fire from Douaumont village ceased. The French had seen the German flares and took the Germans on the fort to be Zouaves retreating from Côte 378. The Germans were able to reach the north-east end of the fort before the French resumed firing. The German party found a way through the railings on top of the ditch and climbed down without being fired on, since the machine-gun bunkers (coffres de contrescarpe) at each corner of the ditch had been left unmanned. The German parties continued and found a way inside the fort through one of the unoccupied ditch bunkers and then reached the central Rue de Rempart.[34]

After quietly moving inside, the Germans heard voices and persuaded a French prisoner, captured in an observation post, to lead them to the lower floor, where they found Warrant Officer Chenot and about 25 French troops, most of the skeleton garrison of the fort, and took them prisoner.[34] On 26 February, the Germans had advanced 3 km (1.9 mi) on a 10 km (6.2 mi) front; French losses were 24,000 men and German losses were c. 25,000 men.[35] A French counter-attack on Fort Douaumont failed and Pétain ordered that no more attempts were to be made; existing lines were to be consolidated and other forts were to be occupied, rearmed and supplied to withstand a siege if surrounded.[36]

27–29 February

The German advance gained little ground on 27 February, after a thaw turned the ground into a swamp and the arrival of French reinforcements increased the effectiveness of the defence. Some German artillery became unserviceable and other batteries became stranded in the mud. German infantry began to suffer from exhaustion and unexpectedly high losses, 500 casualties being suffered in the fighting around Douaumont village.[37] On 29 February, the German advance was contained at Douaumont by a heavy snowfall and the defence of French 33rd Infantry Regiment.[e] Delays gave the French time to bring up 90,000 men and 23,000 short tons (21,000 t) of ammunition from the railhead at Bar-le-Duc to Verdun. The swift German advance had gone beyond the range of artillery covering fire and the muddy conditions made it very difficult to move the artillery forward as planned. The German advance southwards brought it into range of French artillery west of the Meuse, whose fire caused more German infantry casualties than in the earlier fighting, when French infantry on the east bank had fewer guns in support.[39]

Second phase, 6 March – 15 April

6–11 March

Before the offensive, Falkenhayn had expected that French artillery on the west bank would be suppressed by counter-battery fire but this had failed. The Germans set up a specialist artillery force to counter French artillery fire from the west bank but this also failed to reduce German infantry casualties. The 5th Army asked for more troops in late February but Falkenhayn refused, due to the rapid advance already achieved on the east bank and because he needed the rest of the OHL reserve for an offensive elsewhere, once the attack at Verdun had attracted and consumed French reserves. The pause in the German advance on 27 February led Falkenhayn to have second thoughts to decide between terminating the offensive or reinforcing it. On 29 February, Knobelsdorf, the 5th Army Chief of Staff, prised two divisions from the OHL reserve, with the assurance that once the heights on the west bank had been occupied, the offensive on the east bank could be completed. The VI Reserve Corps was reinforced with the X Reserve Corps, to capture a line from the south of Avocourt to Côte 304 north of Esnes, Le Mort Homme, Bois des Cumières and Côte 205, from which the French artillery on the west bank could be destroyed.[40]

The artillery of the two-corps assault group on the west bank was reinforced by 25 heavy artillery batteries, artillery command was centralised under one officer and arrangements were made for the artillery on the east bank to fire in support. The attack was planned by General Heinrich von Gossler in two parts, on Mort-Homme and Côte 265 on 6 March, followed by attacks on Avocourt and Côte 304 on 9 March. The German bombardment reduced the top of Côte 304 from a height of 304 m (997 ft) to 300 m (980 ft); Mort-Homme sheltered batteries of French field guns, which hindered German progress towards Verdun on the right bank; the hills also provided commanding views of the left bank.[41] After storming the Bois des Corbeaux and then losing it to a French counter-attack, the Germans launched another assault on Mort-Homme on 9 March, from the direction of Béthincourt to the north-west. Bois des Corbeaux was captured again at great cost in casualties, before the Germans took parts of Mort-Homme, Côte 304, Cumières and Chattancourt on 14 March.[42]

11 March – 9 April

After a week, the German attack had reached the first-day objectives, to find that French guns behind Côte de Marre and Bois Bourrus were still operational and inflicting many casualties among the Germans on the east bank. German artillery moved to Côte 265, was subjected to systematic artillery fire by the French, which left the Germans needing to implement the second part of the west bank offensive, to protect the gains of the first phase. German attacks changed from large operations on broad fronts, to narrow-front attacks with limited objectives.[43]

On 14 March a German attack captured Côte 265 at the west end of Mort-Homme but the French 75th Infantry Brigade managed to hold Côte 295 at the east end.[44] On 20 March, after a bombardment by 13,000 trench mortar rounds, the 11th Bavarian and 11th Reserve divisions attacked Bois d'Avocourt and Bois de Malancourt and reached their initial objectives easily. Gossler ordered a pause in the attack, to consolidate the captured ground and to prepare another big bombardment for the next day. On 22 March, two divisions attacked "Termite Hill" near Côte 304 but were met by a mass of artillery fire, which also fell on assembly points and the German lines of communication, ending the German advance.[45]

The limited German success had been costly and French artillery inflicted more casualties as the German infantry tried to dig in. By 30 March, Gossler had captured Bois de Malancourt at a cost of 20,000 casualties and the Germans were still short of Côte 304. On 30 March, the XXII Reserve Corps arrived as reinforcements and General Max von Gallwitz took command of a new Attack Group West (Angriffsgruppe West). Malancourt village was captured on 31 March, Haucourt fell on 5 April and Béthincourt on 8 April. On the east bank, German attacks near Vaux reached Bois Caillette and the Vaux–Fleury railway but were then driven back by the French 5th Division. An attack was made on a wider front along both banks by the Germans at noon on 9 April, with five divisions on the left bank but this was repulsed except at Mort-Homme, where the French 42nd Division was forced back from the north-east face. On the right bank an attack on Côte-du-Poivre failed.[44]

In March the German attacks had no advantage of surprise and faced a determined and well-supplied adversary in superior defensive positions. German artillery could still devastate French defensive positions but could not prevent French artillery fire from inflicting many casualties on German infantry and isolating them from their supplies. Massed artillery fire could enable German infantry to make small advances but massed French artillery fire could do the same for French infantry when they counter-attacked, which often repulsed the German infantry and subjected them to constant losses, even when captured ground was held. The German effort on the west bank also showed that capturing a vital point was not sufficient, because it would be found to be overlooked by another terrain feature, which had to be captured to ensure the defence of the original point, which made it impossible for the Germans to terminate their attacks, unless they were willing to retire to the original front line of February 1916.[46]

By the end of March the offensive had cost the Germans 81,607 casualties and Falkenhayn began to think of ending the offensive, lest it become another costly and indecisive engagement similar to the First Battle of Ypres in late 1914. The 5th Army staff requested more reinforcements from Falkenhayn on 31 March with an optimistic report claiming that the French were close to exhaustion and incapable of a big offensive. The 5th Army command wanted to continue the east bank offensive until a line from Ouvrage de Thiaumont, to Fleury, Fort Souville and Fort de Tavannes had been reached, while on the west bank the French would be destroyed by their own counter-attacks. On 4 April, Falkenhayn replied that the French had retained a considerable reserve and that German resources were limited and not sufficient to replace continuously men and munitions. If the resumed offensive on the east bank failed to reach the Meuse Heights, Falkenhayn was willing to accept that the offensive had failed and end it.[47]

Third phase, 16 April – 1 July

April

The failure of German attacks in early April by Angriffsgruppe Ost, led Knobelsdorf to take soundings from the 5th Army corps commanders, who unanimously wanted to continue. The German infantry were exposed to continuous artillery fire from the flanks and rear; communications from the rear and reserve positions were equally vulnerable, which caused a constant drain of casualties. Defensive positions were difficult to build, because existing positions were on ground which had been swept clear by German bombardments early in the offensive, leaving German infantry with very little cover. General Berthold von Deimling, commander of XV Corps, also wrote that French heavy artillery and gas bombardments were undermining the morale of the German infantry, which made it necessary to keep going to reach safer defensive positions. Knobelsdorf reported these findings to Falkenhayn on 20 April, adding that if the Germans did not go forward, they must go back to the start line of 21 February.[48]

Knobelsdorf rejected the policy of limited piecemeal attacks tried by Mudra as commander of Angriffsgruppe Ost and advocated a return to wide-front attacks with unlimited objectives, swiftly to reach the line from Ouvrage de Thiaumont to Fleury, Fort Souville and Fort de Tavannes. Falkenhayn was persuaded to agree to the change and by the end of April, 21 divisions, most of the OHL reserve, had been sent to Verdun and troops had also been transferred from the Eastern Front. The resort to large, unlimited attacks was costly for both sides but the German advance proceeded only slowly. Rather than causing devastating French casualties by heavy artillery with the infantry in secure defensive positions, which the French were compelled to attack, the Germans inflicted casualties by attacks which provoked French counter-attacks and assumed that the process inflicted five French casualties for two German losses.[49]

In mid-March, Falkenhayn had reminded the 5th Army to use tactics intended to conserve infantry, after the corps commanders had been allowed discretion to choose between the cautious, "step by step" tactics desired by Falkenhayn and maximum efforts, intended to obtain quick results. On the third day of the offensive, the 6th Division of the III Corps (General Ewald von Lochow), had ordered that Herbebois be taken regardless of loss and the 5th Division had attacked Wavrille to the accompaniment of its band. Falkenhayn urged the 5th Army to use Stoßtruppen (storm units) composed of two infantry squads and one of engineers, armed with automatic weapons, hand grenades, trench mortars and flame-throwers, to advance in front of the main infantry body. The Stoßtruppen would conceal their advance by shrewd use of terrain and capture any blockhouses which remained after the artillery preparation. Strongpoints which could not be taken were to be by-passed and captured by follow-up troops. Falkenhayn ordered that the command of field and heavy artillery units was to be combined, with a commander at each corps headquarters. Common observers and communication systems would ensure that batteries in different places could bring targets under converging fire, which would be allotted systematically to support divisions.[50]

In mid-April, Falkenhayn ordered that infantry should advance close to the barrage, to exploit the neutralising effect of the shellfire on surviving defenders, because fresh troops at Verdun had not been trained in these methods. Knobelsdorf persisted with attempts to maintain momentum, which was incompatible with casualty conservation by limited attacks, with pauses to consolidate and prepare. Mudra and other commanders who disagreed were sacked. Falkenhayn also intervened to change German defensive tactics, advocating a dispersed defence with the second line to be held as a main line of resistance and jumping-off point for counter-attacks. Machine-guns were to be set up with overlapping fields of fire and infantry given specific areas to defend. When French infantry attacked, they were to be isolated by Sperrfeuer (barrage-fire) on their former front line, to increase French infantry casualties. The changes desired by Falkenhayn had little effect, because the main cause of German casualties was artillery fire, just as it was for the French.[51]

4–22 May

From 10 May German operations were limited to local attacks, either in reply to French counter-attacks on 11 April between Douaumont and Vaux and on 17 April between the Meuse and Douaumont, or local attempts to take points of tactical value. At the beginning of May, General Pétain was promoted to the command of Groupe d'armées du centre (GAC) and General Robert Nivelle took over the Second Army at Verdun. From 4 to 24 May, German attacks were made on the west bank around Mort-Homme and on 4 May, the north slope of Côte 304 was captured; French counter-attacks from 5 to 6 May were repulsed. The French defenders on the crest of Côte 304 were forced back on 7 May but German infantry were unable to occupy the ridge, because of the intensity of French artillery fire. Cumieres and Caurettes fell on 24 May as a French counter-attack began at Fort Douaumont.[52]

22–24 May

In May, General Nivelle, who had taken over the Second Army, ordered General Charles Mangin, commander of the 5th Division to plan a counter-attack on Fort Douaumont. The initial plan was for an attack on a 3 km (1.9 mi) front but several minor German attacks captured the Fausse-Côte and Couleuvre ravines on the south-east and west sides of the fort. A further attack took the ridge south of the ravin de Couleuvre, which gave the Germans better routes for counter-attacks and observation over the French lines to the south and south-west. Mangin proposed a preliminary attack to retake the area of the ravines, to obstruct the routes by which a German counter-attack on the fort could be made. More divisions were necessary but these were refused to preserve the troops needed for the forthcoming offensive on the Somme; Mangin was limited to one division for the attack with one in reserve. Nivelle reduced the attack to an assault on Morchée Trench, Bonnet-d'Evèque, Fontaine Trench, Fort Douaumont, a machine-gun turret and Hongrois Trench, which would require an advance of 500 m (550 yd) on a 1,150 m (1,260 yd) front.[53]

III Corps was to command the attack by the 5th Division and the 71st Brigade, with support from three balloon companies for artillery observation and a fighter group. The main effort was to be conducted by two battalions of the 129th Infantry Regiment, each with a pioneer company and a machine-gun company attached. The 2nd Battalion was to attack from the south and the 1st Battalion was to move along the west side of the fort to the north end, taking Fontaine Trench and linking with the 6th Company. Two battalions of the 74th Infantry Regiment were to advance along the east and south-east sides of the fort and take a machine-gun turret on a ridge to the east. Flank support was arranged with neighbouring regiments and diversions were planned near Fort Vaux and the ravin de Dame. Preparations for the attack included the digging of 12 km (7.5 mi) of trenches and the building of large numbers of depots and stores but little progress was made due to a shortage of pioneers. French troops captured on 13 May, disclosed the plan to the Germans, who responded by subjecting the area to more artillery harassing fire, which also slowed French preparations.[54]

The French preliminary bombardment by four 370 mm mortars and 300 heavy guns, began on 17 May and by 21 May, the French artillery commander claimed that the fort had been severely damaged. During the bombardment the German garrison in the fort experienced great strain, as French heavy shells smashed holes in the walls and concrete dust, exhaust fumes from an electricity generator and gas from disinterred corpses polluted the air. Water ran short but until 20 May, the fort remained operational, reports being passed back and reinforcements moving forward until the afternoon, when the Bourges Casemate was isolated and the wireless station in the north-western machine-gun turret burnt down.[55]

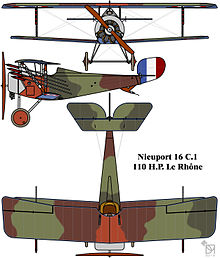

Conditions for the German infantry in the vicinity were far worse and by 18 May, the French destructive bombardment had obliterated many defensive positions, the survivors sheltering in shell-holes and dips of the ground. Communication with the rear was severed and food and water ran out by the time of the French attack on 22 May. The troops of Infantry Regiment 52 in front of Fort Douaumont had been reduced to 37 men near Thiaumont Farm and German counter-barrages inflicted similar losses on French troops. On 22 May, French Nieuport fighters attacked eight observation balloons and shot down six for the loss of one Nieuport 16; other French aircraft attacked the 5th Army headquarters at Stenay.[55] German artillery fire increased and twenty minutes before zero hour, a German bombardment began, which reduced the 129th Infantry Regiment companies to about 45 men each.[56]

The assault began at 11:50 a. m. on 22 May on a 1 km (0.62 mi) front. On the left flank the 36th Infantry Regiment attack quickly captured Morchée Trench and Bonnet-d'Evèque but suffered many casualties and the regiment could advance no further. The flank guard on the right was pinned down, except for one company which disappeared and in Bois Caillette, a battalion of the 74th Infantry Regiment was unable to leave its trenches; the other battalion managed to reach its objectives at an ammunition depot, shelter DV1 at the edge of Bois Caillette and the machine-gun turret east of the fort, where the battalion found its flanks unsupported.[57]

Despite German small-arms fire, the 129th Infantry Regiment reached the fort in a few minutes and managed to get in through the west and south sides. By nightfall, about half of the fort had been recaptured and next day, the 34th Division was sent to reinforce the French troops in the fort. The attempt to reinforce the fort failed and German reserves managed to cut off the French troops inside and force them to surrender, 1,000 French prisoners being taken. After three days, the French had suffered 5,640 casualties from the 12,000 men in the attack and the Germans suffered 4,500 casualties in Infantry Regiment 52, Grenadier Regiment 12 and Leib-Grenadier Regiment 8 of the 5th Division.[57]

30 May – 7 June

Later in May 1916, the German attacks shifted from the left bank at Mort-Homme and Côte 304 to the right bank, south of Fort Douaumont. A German attack to reach Fleury Ridge, the last French defensive line began. The attack was intended to capture Ouvrage de Thiaumont, Fleury, Fort Souville and Fort Vaux at the north-east extremity of the French line, which had been bombarded by c. 8,000 shells a day since the beginning of the offensive. After a final assault on 1 June by about 10,000 German troops, the top of Fort Vaux was occupied on 2 June. Fighting went on underground until the garrison ran out of water, the 574 survivors surrendering on 7 June.[58] When news of the loss of Fort Vaux reached Verdun, the Line of Panic was occupied and trenches were dug on the edge of the city. On the left bank, the German advanced from the line Côte 304, Mort-Homme and Cumières and threatened the French hold on Chattancourt and Avocourt. Heavy rains slowed the German advance towards Fort Souville, where both sides attacked and counter-attacked for the next two months.[59] The 5th Army suffered 2,742 casualties in the vicinity of Fort Vaux from 1 to 10 June, 381 men being killed, 2,170 wounded and 191 missing; French counter-attacks on 8 and 9 June were costly failures.[60]

22–25 June

On 22 June, German artillery fired over 116,000 Diphosgene (Green Cross) gas shells at French artillery positions, which caused over 1,600 casualties and silenced many of the French guns.[61] Next day at 5:00 a.m., the Germans attacked on a 5 km (3.1 mi) front and drove a 3 by 2 km (1.9 by 1.2 mi) salient into the French defences. The advance was unopposed until 9:00 a.m., when some French troops were able to fight a rearguard action. The Ouvrage (shelter) de Thiaumont and the Ouvrage de Froidterre at the south end of the plateau were captured and the villages of Fleury and Chapelle Sainte-Fine were overrun. The attack came close to Fort Souville (which had been hit by c. 38,000 shells since April) bringing the Germans within 5 km (3.1 mi) of the Verdun citadel.[62]

On 23 June 1916, Nivelle ordered,

Vous ne les laisserez pas passer, mes camarades (You will not let them pass, my comrades).[63]

Nivelle had been concerned about declining French morale at Verdun; after his promotion to lead the Second Army in June 1916, Défaillance, manifestations of indiscipline, occurred in five front line regiments.[64] Défaillance reappeared in the French army mutinies that followed the Nivelle Offensive (April–May 1917).[65]

Chapelle Sainte-Fine was quickly recaptured by the French and the German advance was halted. The supply of water to the German infantry broke down, the salient was vulnerable to fire from three sides and the attack could not continue without more Diphosgene ammunition. Chapelle Sainte-Fine became the furthest point reached by the Germans during the Verdun offensive. On 24 June the preliminary Anglo-French bombardment began on the Somme.[62] Fleury changed hands sixteen times from 23 June to 17 August and four French divisions were diverted to Verdun from the Somme. The French artillery recovered sufficiently on 24 June to cut off the German front line from the rear. By 25 June, both sides were exhausted and Knobelsdorf suspended the attack.[66]

Fourth phase 1 July – 17 December

By the end of May French casualties at Verdun had risen to c. 185,000 and in June German losses had reached c. 200,000 men.[67] The Brusilov Offensive (4 June – 20 September 1916) had begun and the opening of the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916), forced the Germans to transfer some of their artillery from Verdun, which was the first strategic success of the Anglo-French offensive.[68]

9–15 July

Fort Souville dominated a crest 1 km (0.62 mi) south-east of Fleury and was one of the original objectives of the February offensive. The capture of the fort would give the Germans control of the heights overlooking Verdun and allow the infantry to dig in on commanding ground.[69] A German preparatory bombardment began on 9 July, with an attempt to suppress French artillery with over 60,000 gas shells, which had little effect since the French had been equipped with an improved M2 gas mask.[70][71] Fort Souville and its approaches were bombarded with more than 300,000 shells, including about 500 360 mm (14 in) shells on the fort.[71]

An attack by three German divisions began on 11 July but German infantry bunched on the path leading to Fort Souville and came under bombardment from French artillery. The surviving troops were fired on by sixty French machine-gunners, who emerged from the fort and took positions on the superstructure. Thirty soldiers of Infantry Regiment 140 managed to reach the top of the fort on 12 July, from where the Germans could see the roofs of Verdun and the spire of the cathedral. After a small French counter-attack, the survivors retreated to their start lines or surrendered.[71] On the evening of 11 July, Crown Prince Wilhelm was ordered by Falkenhayn to go onto the defensive and on 15 July, the French conducted a larger counter-attack which gained no ground; for the rest of the month the French made only small attacks.[72]

1 August – 17 September

On 1 August a German surprise-attack advanced 800–900 m (870–980 yd) towards Fort Souville, which prompted French counter-attacks for two weeks, which were only able to retake a small amount of the captured ground.[72] On 18 August, Fleury was recaptured and by September, French counter-attacks had recovered much of the ground lost in July and August. On 29 August Falkenhayn was replaced as Chief of the General Staff by Paul von Hindenburg and First Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff.[73] On 3 September, an attack on both flanks at Fleury advanced the French line several hundred metres, against which German counter-attacks from 4 to 5 September failed. The French attacked again on 9, 13 and from 15 to 17 September. Losses were light except at the Tavannes railway tunnel, where 474 French troops died in a fire which began on 4 September.[74]

20 October – 2 November

On 20 October 1916 the French began the First Offensive Battle of Verdun (1ère Bataille Offensive de Verdun), to recapture Fort Douaumont, with an advance of more than 2 km (1.2 mi). Seven of the 22 divisions at Verdun were replaced by mid-October and French infantry platoons were reorganised to contain sections of riflemen, grenadiers and machine-gunners. In a six-day preliminary bombardment, the French artillery fired 855,264 shells, including more than half a million 75 mm field-gun shells, a hundred thousand 155 mm medium artillery shells and three hundred and seventy-three 370 mm and 400 mm super-heavy shells, from more than 700 guns and howitzers.[75]

Two French Saint-Chamond railway guns, 13 km (8.1 mi) to the south-west at Baleycourt, fired the 400 mm (16 in) super-heavy shells, each weighing 1 short ton (0.91 t).[75] The French had identified about 800 German guns on the right bank capable of supporting the 34th, 54th, 9th and 33rd Reserve divisions, with the 10th and 5th divisions in reserve.[76] At least 20 of the super-heavy shells hit Fort Douaumont, the sixth penetrating to the lowest level and exploding in a pioneer depot, starting a fire next to 7,000 hand-grenades.[77]

The 38th Division (General Guyot de Salins), 133rd Division (General Fenelon F.G. Passaga) and 74th Division (General Charles de Lardemelle) attacked at 11:40 a.m.[76] The infantry advanced 50 m (55 yd) behind a creeping field-artillery barrage, moving at a rate of 50 m (55 yd) in two minutes, beyond which a heavy artillery barrage moved in 500–1,000 m (550–1,090 yd) lifts, as the field artillery barrage came within 150 m (160 yd), to force the German infantry and machine-gunners to stay under cover.[78] The Germans had partly evacuated Douaumont and it was recaptured on 24 October by French marines and colonial infantry; more than 6,000 prisoners and fifteen guns were captured by 25 October but an attempt on Fort Vaux failed.[79]

The Haudromont quarries, Ouvrage de Thiaumont and Thiaumont Farm, Douaumont village, the northern end of Caillette Wood, Vaux pond, the eastern fringe of Bois Fumin and the Damloup battery were captured.[79] The heaviest French artillery bombarded Fort Vaux for the next week and on 2 November, the Germans evacuated the fort, after a huge explosion caused by a 220 mm shell. French eavesdroppers overheard a German wireless message announcing the departure and a French infantry company entered the fort without firing a shot; on 5 November, the French reached the front line of 24 February and offensive operations ceased until December.[80]

15–17 December 1916

The Second Offensive Battle of Verdun (2ième Bataille Offensive de Verdun) was planned by Pétain and Nivelle and commanded by Mangin. The 126th Division (General Paul Muteau), 38th Division (General Guyot de Salins), 37th Division (General Noël Garnier-Duplessix) and the 133rd Division (General Fénelon Passaga) attacked with four more in reserve and 740 heavy guns in support.[81] The attack began at 10:00 a.m. on 15 December, after a six-day bombardment of 1,169,000 shells, fired from 827 guns. The final French bombardment was directed from artillery-observation aircraft, falling on trenches, dugout entrances and observation posts. Five German divisions supported by 533 guns held the defensive position, which was 2,300 m (1.4 mi; 2.3 km) deep, with 2⁄3 of the infantry in the battle zone and the remaining 1⁄3 in reserve 10–16 km (6.2–9.9 mi) back.[82]

Two of the German divisions were understrength with only c. 3,000 infantry, instead of their normal establishment of c. 7,000. The French advance was preceded by a double creeping barrage, with shrapnel-fire from field artillery 64 m (70 yd) in front of the infantry and a high-explosive barrage 140 m (150 yd) ahead, which moved towards a standing shrapnel bombardment along the German second line, laid to cut off the German retreat and block the advance of reinforcements. The German defence collapsed and 13,500 men of the 21,000 in the five front divisions were lost, most having been trapped while under cover and taken prisoner when the French infantry arrived.[82]

The French reached their objectives at Vacherauville and Louvemont which had been lost in February, along with Hardaumont and Louvemont-Côte-du-Poivre, despite attacking in very bad weather. German reserve battalions did not reach the front until the evening and two Eingreif divisions, which had been ordered forward the previous evening, were still 23 km (14 mi) away at noon. By the night of 16/17 December, the French had consolidated a new line from Bezonvaux to Côte du Poivre, 2–3 km (1.2–1.9 mi) beyond Douaumont and 1 km (0.62 mi) north of Fort Vaux, before the German reserves and Eingreif units could counter-attack. The 155 mm turret at Douaumont had been repaired and fired in support of the French attack.[83] The closest German point to Verdun had been pushed 7.5 km (4.7 mi) back and all the dominating observation points had been recaptured. The French took 11,387 prisoners and 115 guns.[84] Some German officers complained to Mangin about their lack of comfort in captivity and he replied, We do regret it, gentlemen, but then we did not expect so many of you.[85][f] Lochow, the 5th Army commander and General Hans von Zwehl, commander of XIV Reserve Corps, were sacked on 16 December.[86]

Aftermath

Analysis

Falkenhayn wrote in his memoirs that he sent an appreciation of the strategic situation to the Kaiser in December 1915,

The string in France has reached breaking point. A mass breakthrough—which in any case is beyond our means—is unnecessary. Within our reach there are objectives for the retention of which the French General Staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have. If they do so the forces of France will bleed to death.

— Falkenhayn[1]

The German strategy in 1916 was to inflict mass casualties on the French, a goal achieved against the Russians from 1914 to 1915, to weaken the French Army to the point of collapse. The French had to be drawn into circumstances from which the Army could not escape, for reasons of strategy and prestige. The Germans planned to use a large number of heavy and super-heavy guns to inflict a greater number of casualties than French artillery, which relied mostly upon the 75 mm field gun. In 2007, Robert Foley wrote that Falkenhayn intended a battle of attrition from the beginning, contrary to the views of Wolfgang Foerster in 1937, Gerd Krumeich in 1996 and others but the loss of documents led to many interpretations of the strategy. In 1916, critics of Falkenhayn claimed that the battle demonstrated that he was indecisive and unfit for command, echoed by Foerster in 1937.[87] In 1994, Holger Afflerbach questioned the authenticity of the "Christmas Memorandum"; after studying the evidence that had survived in the Kriegsgeschichtliche Forschungsanstalt des Heeres (Army Military History Research Institute) files, he concluded that the memorandum had been written after the war but that it was an accurate reflection of Falkenhayn's thinking at the end of 1915.[88]

Krumeich wrote that the Christmas Memorandum was fabricated to justify a failed strategy and that attrition had been substituted for the capture of Verdun only after the attack failed.[89] Foley wrote that after the failure of the Ypres Offensive of 1914, Falkenhayn had returned to the pre-war strategic thinking of Moltke the Elder and Hans Delbrück on Ermattungsstrategie (attrition strategy), because the coalition fighting Germany was too powerful to be defeated decisively. Falkenhayn wanted to divide the Allies by forcing at least one of the Entente powers into a negotiated peace. An attempt at attrition lay behind the offensive in the east in 1915 but the Russians had refused to accept German peace feelers, despite the huge defeats inflicted on them by the Austro-Germans.[90]

With insufficient forces to break through the Western Front and to overcome the reserves behind it, Falkenhayn tried to force the French to attack instead, by threatening a sensitive point close to the front line and chose Verdun. Huge losses were to be inflicted on the French by German artillery on the dominating heights around the city. The 5th Army would begin a big offensive but with the objectives limited to seizing the Meuse Heights on the east bank, on which the German heavy artillery would dominate the battlefield. The French Army would "bleed itself white" in hopeless attempts to recapture the heights. The British would be forced to launch a hasty relief offensive and suffer an equally costly defeat. If the French refused to negotiate, a German offensive would mop up the remnants of the Franco-British armies, breaking the Entente "once and for all".[90]

In a revised instruction to the French Army in January 1916, the General Staff (GQG) wrote that equipment could not be fought by men. Firepower could conserve infantry but attrition prolonged the war and consumed troops that had been preserved in earlier battles. In 1915 and early 1916, German industry quintupled the output of heavy artillery and doubled the production of super-heavy artillery. French production had also recovered since 1914 and by February 1916 the army had 3,500 heavy guns. In May Joffre began to issue each division with two groups of 155 mm guns and each corps with four groups of long-range guns. Both sides at Verdun had the means to fire huge numbers of heavy shells to suppress the opposing defences before risking infantry in the open. At the end of May, the Germans had 1,730 heavy guns at Verdun and the French 548, sufficient to contain the Germans but not enough for a counter-offensive.[91]

French infantry survived bombardment better because their positions were dispersed and tended to be on dominating ground, not always visible to the Germans. As soon as a German attack began, the French replied with machine-gun and rapid field-artillery fire. On 22 April, the Germans suffered 1,000 casualties and in mid-April, the French fired 26,000 field artillery shells against an attack to the south-east of Fort Douaumont. A few days after taking over at Verdun, Pétain ordered the air commander, Commandant Charles Tricornot de Rose to sweep away German fighter aircraft and to provide artillery observation. German air superiority was reversed by concentrating the French fighters in escadrilles rather than distributing them piecemeal across the front, unable to concentrate against large German formations. The fighter escadrilles drove away the German Fokker Eindeckers and the two-seater reconnaissance and artillery-observation aircraft that they protected.[92]

The fighting at Verdun was less costly to both sides than the war of movement in 1914, when the French suffered c. 850,000 casualties and the Germans c. 670,000 from August to the end of 1914. The 5th Army had a lower rate of loss than armies on the Eastern Front in 1915 and the French had a lower average rate of loss at Verdun than the rate over three weeks during the Second Battle of Champagne (September–October 1915), which were not deliberately fought as battles of attrition. German loss rates increased relative to losses from 1:2.2 in early 1915 to close to 1:1 by the end of the battle, a trend which continued during the Nivelle Offensive in 1917. The penalty of attrition tactics was indecision, because limited-objective attacks under an umbrella of massed heavy artillery fire could succeed but led to battles of unlimited duration.[93] Pétain used a noria (rotation) system quickly to relieve French troops at Verdun, which involved most of the French Army in the battle but for shorter periods than the German troops in the 5th Army. The symbolic importance of Verdun proved a rallying point and the French did not collapse. Falkenhayn was forced to conduct the offensive for much longer and commit far more infantry than intended. By the end of April, most of the German strategic reserve was at Verdun, suffering similar casualties to the French army.[94]

The Germans believed that they were inflicting losses at a rate of 5:2; German military intelligence thought that by 11 March the French had suffered 100,000 casualties and Falkenhayn was confident that German artillery could easily inflict another 100,000 losses. In May, Falkenhayn estimated that French casualties had increased to 525,000 men against 250,000 German and that the French strategic reserve was down to 300,000 men. Actual French losses were c. 130,000 by 1 May; 42 French divisions had been withdrawn and rested by the noria system, once infantry casualties reached 50 percent. Of the 330 infantry battalions of the French metropolitan army, 259 (78 per cent) went to Verdun, against 48 German divisions, 25 percent of the Westheer (western army).[95] Afflerbach wrote that 85 French divisions fought at Verdun and that from February to August, the ratio of German to French losses was 1:1.1, not the third of French losses assumed by Falkenhayn.[96] By 31 August, the 5th Army had suffered 281,000 casualties and the French 315,000.[94]

In June 1916, the French had 2,708 guns at Verdun, including 1,138 field guns; from February to December, the French and German armies fired c. 10,000,000 shells, weighing 1,350,000 long tons (1,371,663 t).[97] By May, the German offensive had been defeated by French reinforcements, difficulties of terrain and the weather. The 5th Army infantry was stuck in tactically dangerous positions, overlooked by the French on both banks of the Meuse, instead of dug in on the Meuse Heights. French casualties were inflicted by constant infantry attacks which were far more costly in men than destroying counter-attacks with artillery. The stalemate was broken by the Brusilov Offensive and the Anglo-French relief offensive on the Somme, which Falkehayn had expected to begin the collapse of the Anglo-French armies.[98] Falkenhayn had begun to remove divisions from the Western Front in June for the strategic reserve but only twelve divisions could be spared. Four divisions were sent to the Somme, where three defensive positions had been built, based on the experience of the Herbstschlacht. Before the battle on the Somme began, Falkenhayn thought that German preparations were better than ever and the British offensive would easily be defeated. The 6th Army, further north, had 17+1⁄2 divisions and plenty of heavy artillery, ready to attack once the British had been defeated.[99]

The strength of the Anglo-French attack on the Somme surprised Falkenhayn and his staff, despite the British casualties on 1 July. Artillery losses to "overwhelming" Anglo-French counter-battery fire and the German tactic of instant counter-attacks, led to far more German infantry casualties than at the height of the fighting at Verdun, where the 5th Army suffered 25,989 casualties in the first ten days, against 40,187 2nd Army casualties on the Somme. The Russians attacked again, causing more casualties in June and July. Falkenhayn was called on to justify his strategy to the Kaiser on 8 July and again advocated the minimal reinforcement of the east in favour of the "decisive" battle in France; the Somme offensive was the "last throw of the dice" for the Entente. Falkenhayn had already given up the plan for a counter-offensive by the 6th Army and sent 18 divisions to the 2nd Army and to the Russian front from the reserve and from the 6th Army; only one division remaining uncommitted by the end of August. The 5th Army had been ordered to limit its attacks at Verdun in June but a final effort was made in July to capture Fort Souville. The attack failed and on 12 July Falkenhayn ordered a strict defensive policy, permitting only small local attacks to limit the number of troops the French could transfer to the Somme.[100]

Falkenhayn had underestimated the French, for whom victory at all costs was the only way to justify the sacrifices already made; the French army never came close to collapsing and causing a premature British relief offensive. The ability of the German army to inflict disproportionate losses had also been overestimated, in part because the 5th Army commanders had tried to capture Verdun and attacked regardless of loss. Even when reconciled to the attrition strategy, they continued with Vernichtungsstrategie (strategy of annihilation) and the tactics of Bewegungskrieg (manoeuvre warfare). Failure to reach the Meuse Heights left the 5th Army in poor tactical positions and reduced to inflicting casualties by infantry attacks and counter-attacks. The length of the offensive made Verdun a matter of prestige for the Germans as it was for the French and Falkenhayn became dependent on a British relief offensive being destroyed to end the stalemate. When it came, the collapse in Russia and the power of the Anglo-French attack on the Somme reduced the German armies to holding their positions as best they could.[101] On 29 August, Falkenhayn was sacked and replaced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, who ended the German offensive at Verdun on 2 September.[102][g]

Casualties

In 2013, Paul Jankowski wrote that since the beginning of the war, French army units had produced numerical loss states (états numériques des pertes) every five days for the Bureau of Personnel at GQG. The Health Service (Service de Santé) at the Ministry of War received daily counts of wounded taken in by hospitals and other services but casualty data was dispersed among regimental depots, GQG, the Registry Office (État Civil), which recorded deaths, the Service de Santé, which counted injuries and illnesses, and Renseignements aux Familles (Family Liaison), which communicated with next of kin. Regimental depots were ordered to keep fiches de position (position sheets) to record losses continuously and the Première Bureau of GQG began to compare the five-day états numériques des pertes with the records of hospital admissions. The new system was used to calculate losses back to August 1914, which took several months; the system had become established by February 1916. The états numériques des pertes were used to calculate casualty figures published in the Journal Officiel, the French Official History and other publications.[105]

The German armies compiled Verlustlisten (loss lists) every ten days, which were published by the Reichsarchiv in the deutsches Jahrbuch of 1924–1925. German medical units kept detailed records of medical treatment at the front and in hospital and in 1923 the Zentral Nachweiseamt (Central Information Office) published an amended edition of the lists produced during the war, incorporating medical service data not in the Verlustlisten. Monthly figures of wounded and ill servicemen that received medical treatment were published in 1934 in the Sanitätsbericht (Medical Report). Using such sources for comparison is difficult, because the information recorded losses over time, rather than place. Losses calculated for a battle could be inconsistent, as in the Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914–1920 (1922). In the early 1920s, Louis Marin reported to the Chamber of Deputies but could not give figures per battle, except for some by using numerical reports from the armies, which were unreliable unless reconciled with the system established in 1916.[106]

Some French data excluded those lightly wounded but some did not. In April 1917, GQG required that the états numériques des pertes discriminate between lightly wounded, treated locally for 20 to 30 days and severely wounded evacuated to hospitals. Uncertainty over the criteria had not been resolved before the war ended. Verlustlisten excluded lightly wounded and the Zentral Nachweiseamt records included them. Churchill revised German statistics by adding 2 per cent for unrecorded wounded in The World Crisis, written in the 1920s and James Edmonds, the British official historian, added 30 per cent. For the Battle of Verdun, the Sanitätsbericht contained incomplete data for the Verdun area, did not define "wounded" and the 5th Army field reports exclude them. The Marin Report and Service de Santé covered different periods but included lightly wounded. Churchill used a Reichsarchiv figure of 428,000 casualties and took a figure of 532,500 casualties from the Marin Report, for March to June and November to December 1916, for all the Western Front.[107]

The états numériques des pertes give French casualties as 348,000 to 378,000 and in 1930, Hermann Wendt recorded French Second Army and German 5th Army casualties of 362,000 and 336,831 respectively from 21 February to 20 December, not taking account of the inclusion or exclusion of lightly wounded. In 2006, McRandle and Quirk used the Sanitätsbericht to increase the Verlustlisten by c. 11 per cent, which gave 373,882 casualties, compared to the French Official History record to 20 December 1916, of 373,231 French casualties. The Sanitätsbericht, which explicitly excluded lightly wounded, compared German losses at Verdun in 1916, averaging 37.7 casualties per thousand men, with the 9th Army in Poland 1914 which had a casualty average of 48.1 per 1,000, the 11th Army in Galicia 1915 averaging 52.4 per 1,000 men, the 1st Army on the Somme 1916 average of 54.7 per 1,000 and the 2nd Army average for the Somme 1916 of 39.1 per 1,000 men. Jankowski estimated an equivalent figure for the French Second Army of 40.9 men per 1,000 including lightly wounded. With a c. 11 per cent adjustment to the German figure of 37.7 per 1,000 to include lightly wounded, following the views of McRandle and Quirk; the loss rate is similar to the estimate for French casualties.[108]

In the second edition of The World Crisis (1938), Churchill wrote that the figure of 442,000 was for other ranks and the figure of "probably" 460,000 casualties included officers. Churchill gave a figure of 278,000 German casualties, 72,000 fatal and expressed dismay that French casualties had exceeded German by about 3:2. Churchill wrote that an eighth needed to be deducted from his figures to account for casualties on other sectors, giving 403,000 French and 244,000 German casualties.[109] In 1980, John Terraine calculated c. 750,000 French and German casualties in 299 days; Dupuy and Dupuy (1993) 542,000 French casualties.[110] In 2000, Hannes Heer and Klaus Naumann calculated 377,231 French and 337,000 German casualties, a monthly average of 70,000.[111] In 2000, Holger Afflerbach used calculations made by Hermann Wendt in 1931 to give German casualties at Verdun from 21 February to 31 August 1916 as 336,000 German and 365,000 French at Verdun from February to December 1916.[112] David Mason wrote in 2000 that there had been 378,000 French and 337,000 German casualties.[97] In 2003, Anthony Clayton quoted 330,000 German casualties, of whom 143,000 were killed or missing; the French suffered 351,000 casualties, 56,000 killed, 100,000 missing or prisoners and 195,000 wounded.[113]

Writing in 2005, Robert A. Doughty gave French casualties (21 February to 20 December 1916) as 377,231 and casualties of 579,798 at Verdun and the Somme; 16 per cent of the casualties at Verdun were fatal, 56 per cent were wounded and 28 per cent missing, many of whom were eventually presumed dead. Doughty wrote that other historians had followed Winston Churchill (1927) who gave a figure of 442,000 casualties by mistakenly including all French losses on the Western Front.[114] R. G. Grant gave a figure of 355,000 German and 400,000 French casualties in 2005.[115] In 2005, Robert Foley used the Wendt calculations of 1931 to give German casualties at Verdun from 21 February to 31 August 1916 of 281,000, against 315,000 French.[116] (In 2014, William Philpott recorded 377,000 French casualties, of whom 162,000 had been killed; German casualties were 337,000 and noted a recent estimate of casualties at Verdun from 1914 to 1918 of 1,250,000).[117]

Morale

Fighting in such a small area devastated the land, resulting in miserable conditions for troops on both sides. Rain and the constant artillery bombardments turned the clayey soil into a wasteland of mud full of debris and human remains; shell craters filled with water and soldiers risked drowning in them. Forests were reduced to tangled piles of wood by artillery fire and eventually obliterated.[95] The effect of the battle on many soldiers was profound and accounts of men breaking down with insanity and shell shock were common. Some French soldiers tried to desert to Spain and faced court-martial and execution if captured; on 20 March, French deserters disclosed details of French defences to the Germans, who were able to surround 2,000 men and force them to surrender.[95]

A French lieutenant wrote,

Humanity is mad. It must be mad to do what it is doing. What a massacre! What scenes of horror and carnage! I cannot find words to translate my impressions. Hell cannot be so terrible. Men are mad!

— (Diary 23 May 1916)[118]

Discontent began to spread among French troops at Verdun; after the promotion of Pétain from the Second Army on 1 June and his replacement by Nivelle, five infantry regiments were affected by episodes of "collective indiscipline"; Lieutenants Henri Herduin and Pierre Millant were summarily shot on 11 June and Nivelle published an Order of the Day forbidding surrender.[119] In 1926, after an inquiry into the cause célèbre, Herduin and Millant were exonerated and their military records expunged.[120]

Subsequent operations

20–26 August 1917

The French planned an attack on a 9 km (5.6 mi) front on both sides of the Meuse; XIII Corps and XVI Corps to attack on the left bank with two divisions each and two in reserve. Côte 304, Mort-Homme and Côte (hill) de l'Oie were to be captured in a 3 km (1.9 mi) advance. On the right (east) bank, XV Corps and XXXII Corps were to advance a similar distance and take Côte de Talou, hills 344, 326 and the Bois de Caurières. About 34 km (21 mi) of 6 m (6.6 yd) wide road was rebuilt and paved for the supply of ammunition, along with a branch of the 60 cm (2.0 ft) light railway. The French artillery prepared the attack with 1,280 field guns, 1.520 heavy guns and howitzers and 80 super-heavy guns and howitzers. The Aéronautique Militaire crowded 16 escadrilles de chasse into the area to escort reconnaissance aircraft and protect observation balloons. The 5th Army had spent a year improving their defences at Verdun, including the excavation of tunnels linking Mort-Homme with the rear, to deliver supplies and infantry with impunity. On the right bank, the Germans had developed four defensive positions, the last on the French front line of early 1916.[121]