Province of Maryland

Maryland Palatinate Province of Maryland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1632–1776 | |||||||||

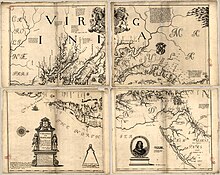

Map of the Province of Maryland in 1776; Many Palatines settled in Western Maryland | |||||||||

| Status | Proprietary Palatinate (1632–1654) Colony of England (1634–1707) Colony of Great Britain (1707–1776) | ||||||||

| Capital | St. Mary's City (1634–1695) Annapolis (from 1695) | ||||||||

| Common languages | English, Palatine German, Susquehannock, Nanticoke, Piscataway | ||||||||

| Religion | Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Proprietary colony | ||||||||

| Royal Proprietor | |||||||||

• 1634–1675 | Lord Baltimore, 2nd | ||||||||

• 1751–1776 | Lord Baltimore, 6th | ||||||||

| Proprietary Governor | |||||||||

• 1634–1647 | Leonard Calvert | ||||||||

• 1769–1776 | Robert Eden | ||||||||

| Legislature | General Assembly (1634-1774) Annapolis Convention (1774-1776) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1632 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1776 | ||||||||

| Currency | Maryland pound | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||

The Province of Maryland[1] was an English and later British colony in North America from 1634[2] until 1776, when the province was one of the Thirteen Colonies that joined in supporting the American Revolution against Great Britain. In 1781, Maryland was the 13th signatory to the Articles of Confederation. The province's first settlement and capital was in St. Mary's City, located at the southern end of St. Mary's County, a peninsula in the Chesapeake Bay bordered by four tidal rivers.

The province began in 1632 as the Maryland Palatinate,[3] a proprietary palatinate granted to Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, whose father, George, had long sought to found a colony in the New World to serve as a refuge for Catholics at the time of the European wars of religion. Palatines from the Holy Roman Empire also immigrated to Maryland, with many settling in Fredrick County, with Maryland Palatines (Palatine German: Marylandisch Pälzer) reaching a population of 50,000 by 1774.[4]

Provincial Maryland served as an early pioneer of religious toleration in the English colonies. However, religious strife among Anglicans, Puritans, Catholics, and Quakers was common in the early years and Puritan rebels briefly seized control of the province. Later, in 1689, the year following the Glorious Revolution in Great Britain, John Coode led a rebellion that removed Lord Baltimore, a Catholic, from power in Maryland. That power was restored to the Baltimore family in 1715 after Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, declared in public that he was a Protestant.

Despite early competition with the colony of Virginia to its south, and the Holland Dutch colony of New Netherland to its north, the province of Maryland developed along similar lines to Virginia. Its early settlements and population centers tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay, and, like Virginia, Maryland's economy quickly became centered on the cultivation of tobacco for sale in Europe.

However, after tobacco prices collapsed, the need for cheap labor to accommodate the mixed farming economy that followed led to a rapid expansion of the Atlantic slave trade and the concomitant American enslavement of Africans—as well as the expansion of indentured servitude and British penal transportation. Maryland received a larger felon quota than any other province.[5]

Maryland was an active participant in the events leading up to the American Revolution, echoing events in New England by establishing committees of correspondence and hosting its own tea party similar to the one that took place in Boston. By 1776 the old order had been overthrown as Maryland's colonial representatives signed the Declaration of Independence, presaging the end of British colonial rule.

Origins in the 17th century

[edit]| History of Maryland |

|---|

|

|

Founding charter

[edit]

The Catholic George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (1579–1632), former Secretary of State to King Charles I of England, wished to create a haven for English Catholics in the New World. After having visited the Americas and founded a colony in the future Canadian province of Newfoundland called "Avalon", he convinced the King to grant him a second territory in more southern, temperate climes. Upon Baltimore's death in 1632 the grant was transferred to his eldest son Cecil, the 2nd Baron Baltimore.

On June 20, 1632, Charles granted the original charter for Maryland, a proprietary colony of about twelve million acres (49,000 km2), to the 2nd Baron Baltimore. Some historians view this grant as a form of compensation for the 2nd Lord Baltimore's father's having been stripped of his title of Secretary of State upon announcing his Catholicism in 1625. [6]

Whatever the reason for granting the colony specifically to Lord Baltimore, however, the King had practical reasons to create a colony north of the Potomac in 1632. The colony of New Netherland begun by England's great imperial rival in this era, the United Provinces, specifically claimed the Delaware River valley and was vague about its border with Virginia. Charles rejected all the Dutch claims on the Atlantic seaboard, but was anxious to bolster English claims by formally occupying the territory. The new colony was named after the devoutly Catholic Queen Henrietta Maria,[7] by an agreement between the 1st Lord Baltimore and King Charles I.[8]

Colonial Maryland was considerably larger than the present-day State of Maryland. The original charter granted the Calverts a province with a boundary line that started "from the promontory or headland, called Watkin's Point, situate upon the bay aforesaid near the river Wighco on the West, unto the main ocean on the east; and between that boundary on the south, unto that part of the bay of Delaware on the north, which lyeth under the 40th degree of north latitude from the aequinoctial, where New England is terminated."[9]p. 116 The boundary line would then continue westward along the fortieth parallel "unto the true meridian of the first fountain of the river Pattowmack". From there, the boundary continued south to the southern bank of the Potomac River, continue along the southern river bank to the Chesapeake Bay, and "thence by the shortest line unto the aforesaid promontory, or place, called Watkin's Point."[9]p. 38. Based on this deceptively imprecise description of the boundary, the land may have comprised up to 18,750 square miles (48,600 km2), 50% larger than today's State.[10]

Early settlement

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2018) |

In Maryland, Baltimore sought to create a haven for English Catholics and to demonstrate that Catholics and Protestants could live together peacefully, even issuing the Act Concerning Religion in matters of religion. The 1st Lord Baltimore was himself a convert to Catholicism, a considerable political setback for a nobleman in 17th-century England, where Catholics could easily be considered enemies of the crown and potential traitors to their country. Like other aristocratic proprietors, he also hoped to turn a profit on the new colony.

The Calvert family recruited Catholic aristocrats and Protestant settlers for Maryland, luring them with generous land grants and a policy of religious toleration. To try to gain settlers, Maryland used what is known as the headright system, which originated in Jamestown. Settlers were given 50 acres (20 ha) of land for each person they brought into the colony, whether as settler, indentured servant, or slave.

Of the 200 or so initial settlers who traveled to Maryland on the ships Ark and Dove, the majority were Protestant.[11] On November 22, 1633, Lord Baltimore sent the first settlers to the new colony, and after a long voyage with a stopover to resupply in Barbados, the Ark and the Dove landed on March 25, 1634 (thereafter celebrated as "Maryland Day"), at Blackistone Island, thereafter known as St. Clement's Island, off the northern shore of the Potomac River, upstream from its confluence with the Chesapeake Bay and Point Lookout. The new settlers were led by Lord Baltimore's younger brother the Honorable Leonard Calvert, whom Baltimore had delegated to serve as governor of the new colony.[11]

The Native Americans in Maryland were a peaceful people who welcomed the English. At the time of the founding of the Maryland colony, approximately forty tribes consisting of 8,000 – 10,000 people lived in the area. They were fearful of the colonists' guns, but welcomed trade for metal tools. The Native Americans who were living in the location where the colonists first settled were called the Yaocomico Indians. The colonists gave the Yaocomico Indians cloth, hatchets, and hoes in exchange for the right to settle on the land. The Yaocomico Indians allowed the English settlers to live in their houses, a type of longhouse called a witchott. The Indians also taught the colonists how to plant corn, beans, and squash, as well as where to find food such as clams and oysters.[12][13]

Here at St. Clement's Island they raised a large cross, and led by Jesuit Father Andrew White celebrated Mass. The new settlement was called "St. Mary's City" and it became the first capital of Maryland. It remained so for sixty years until 1695 when the colony's capital was moved north to the more central, newly established "Anne Arundel's Town (also briefly known as "Providence") and later renamed as "Annapolis".

More settlers soon followed. The tobacco crops that they had planted from the outset were very successful and quickly made the new colony profitable. However, given the incidence of malaria and typhoid, life expectancy in Maryland was about 10 years less than in New England.[14]

"Historic St. Mary's City" (a historic preservationist/tourism agency) has been established to protect what is left of the ruins of the original 17th-century village, and several reconstructed, government buildings, little of which remained intact. With the exception of several periods of rebellion by early Protestants and later colonists, the colony/province remained under the control of the several Lords Baltimore until 1775–1776, when it joined with other colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and eventually became the independent and sovereign U.S. State of Maryland.

Relations with the Susquehannock

[edit]The establishment of the Province of Maryland disrupted the trade relationship between Virginia colonists and the Susquehannock, an Iroquoian-speaking tribe that lived in the lower Susquehanna River valley. Following a raid on a Jesuit mission in 1641, the Governor of Maryland declared the Susquehannock "enemies of the province." A few attempts were made to organize a military campaign, however, it was not until 1643 that an ill-fated expedition was mounted. The Susquehannock inflicted numerous casualties on the English and captured two cannon. 15 prisoners were taken and afterwards tortured to death.[15]

Raids on Maryland continued intermittently until 1652. In the winter of 1652, the Susquehannock were attacked by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), and although the attack was repulsed, it led to the Susquehannock negotiating the Articles of Peace and Friendship with Maryland.[15] The Susquehannock relinquished their claim to territory on either side of Chesapeake Bay, and reestablished a trading relationship with the English.[16][17]

A Haudenosaunee raid in 1660 led Maryland to expand its treaty with the Susquehannock into an alliance. The Maryland assembly authorized armed assistance, and described the Susquehannock as "a Bullwarke and Security of the Northern Parts of this Province." A detachment of 50 soldiers was sent to help defend the Susquehannock town against Haudenosaunee attacks. Despite suffering a smallpox epidemic in 1661, the Susquehannock easily withstood a siege in 1663, and destroyed a Haudenosaunee war party in 1666.[15]

By 1675, epidemics and years of war had taken their toll on the Susquehannock. They abandoned their village on the Susquehanna River and moved south into Maryland. Governor Charles Calvert invited them to settle on the Potomac River above the Great Falls, however, the Susquehannock instead chose to occupy a site on Piscataway Creek where they erected a palisaded fort. In July 1675, a group of Virginians chasing Doeg raiders crossed the Potomac into Maryland and mistakenly killed several Susquehannock. Subsequent raids in Virginia and Maryland were blamed on the tribe. In September 1675, a thousand-man expedition against the Susquehannock was mounted by militia from Virginia and Maryland led by John Washington and Thomas Truman. After arriving at the Susquehannock town, Truman and Washington summoned five sachems to a parley, but then had them summarily executed. Sorties during the ensuing six-week siege resulted in 50 English deaths. In early November, the Susquehannock escaped the siege under cover of darkness, killing ten of the militia as they slept.[18]

Most of Susquehannock crossed the Potomac and took refuge in the Piedmont of Virginia. Two encampments were established on the Meherrin River near the village of the Siouan-speaking Occaneechi. In January 1676, the Susquehannock raided plantations in Virginia, killing 36 colonists. Nathaniel Bacon, unhappy with Governor Sir William Berkeley's response to the raids, organized a volunteer militia to hunt down the Susquehannock. Bacon persuaded the Occaneechi to attack the closest Susquehannock encampment. After the Occaneechi returned with Susquehannock prisoners, Bacon turned on his allies and indiscriminately massacred Occaneechi men, women and children.[18]

Other Susquehannock refugees fled to hunting camps on the North Branch of the Potomac or took refuge with the Lenape. Some refugees returned to the Susquehanna River in 1676 and established a palisaded village near the site of their previous village. This village was also abandoned when the inhabitants merged with the Haudenosaunee a few years later.[19]

Border disputes

[edit]

With Virginia

[edit]In 1629, George Calvert, 1st Lord Baltimore, "driven by 'the sacred duty of finding a refuge for his Catholic brethren'",[20] applied to Charles I for a royal charter to establish a colony south of Virginia. He also wanted a share of the fortunes being made in tobacco in Virginia, and hoped to recoup some of the financial losses he had sustained in his earlier colonial venture in Newfoundland.[21]

In 1631, William Claiborne, a Puritan from Virginia, received a royal trading commission granting him the right to trade with the natives in all lands in the mid-Atlantic where there was not already a patent in effect.[22] Claiborne established a trading post on Kent Island on May 28, 1631.

Meanwhile, back in London, the Privy Council persuaded Lord Baltimore to accept instead a charter for lands north of the Virginia colony, in order to put pressure on the Dutch settlements further north along the Delaware and Hudson Rivers. Calvert agreed, but died in 1632 before the charter was formally signed by King Charles I. The Royal Grant and Charter for the new colony of Maryland was then granted to his son, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, on June 20, 1632.[22] This placed Claiborne on Calvert land. Claiborne refused to recognize Lord Baltimore's charter and rights, or the authority of his brother Leonard as governor.

Following the arrest of one of his agents for trading in Maryland waters without a license in 1635, Claiborne fitted out an armed ship. There ensued a naval battle on April 23, 1635, by the mouth of the Pocomoke River during which three Virginians were killed. Following this battle, Leonard Calvert captured Kent Island by force in February 1638.[23]

In 1644, during the English Civil War, Claiborne led an uprising of Protestants in what came to be called the Plundering Time, also known as "Claiborne and Ingle's Rebellion", and retook Kent Island. Meanwhile, privateer Captain Richard Ingle (Claiborne's co-commander) seized control of St. Mary's City, the capital of the Maryland colony. Catholic Governor Calvert escaped to the Virginia Colony which remained nominally loyal to the crown until 1652.[24] The Protestant pirates began plundering the property of anyone who did not swear allegiance to the Parliament of England, mainly Catholics. The rebellion was put down in 1647 by Governor Calvert.

The victory of Parliament in England renewed old tensions. This led to the 1655 Battle of the Severn, at the settlement of "Providence" (present-day Annapolis, Maryland). Moderate Protestants and Catholics loyal to Lord Baltimore, under the command of William Stone, met Puritans loyal to the Commonwealth of England from Providence under the command of Captain William Fuller. 17 of Stone's men and two Puritans were killed, resulting in victory for the Puritans.

The issue of the ongoing Claiborne grievance was finally settled by an agreement reached in 1657. Lord Baltimore gave Claiborne amnesty for all of his offenses, Virginia laid aside any claim it had to Maryland territory, and Claiborne was indemnified with extensive land grants in Virginia for his loss of Kent Island.[25]

"Multiple colonial charters, two negotiated settlements by the states in 1785 and 1958, an arbitrated agreement in 1877, and several Supreme Court decisions have defined how Maryland and Virginia would deal with the Potomac River as a boundary line, and shaped the boundary on the Eastern Shore (separating Accomack County, Virginia, from Worcester and Somerset counties in Maryland)."[26]

With Pennsylvania

[edit]The border dispute with Pennsylvania continued and led to Cresap's War, a conflict between settlers from Pennsylvania and Maryland fought in the 1730s. Hostilities erupted in 1730 with a series of violent incidents prompted by disputes over property rights and law enforcement, and escalated through the first half of the decade, culminating in the deployment of military forces by Maryland in 1736 and by Pennsylvania in 1737. The armed phase of the conflict ended in May 1738 with the intervention of King George II, who compelled the negotiation of a cease-fire. A provisional agreement had been established in 1732.[27]

Maryland lost some of its original territory to Pennsylvania in the 1660s when King Charles II granted the Penn family, owners of Pennsylvania, a tract that overlapped the Calvert family's Maryland grant. For 80 years the powerful Penn and Calvert families had feuded over overlapping Royal grants. Surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon mapped the Maryland-Pennsylvania border in 1767, setting out the Mason–Dixon line.[28]

With New York

[edit]In 1672, Lord Baltimore declared that Maryland included the settlement of Whorekills on the west shore of the Delaware Bay, an area under the jurisdiction of the Province of New York (as the British had renamed New Netherland after taking possession in 1664). A force was dispatched which attacked and captured this settlement. New York could not immediately respond because New York was soon recaptured by the Dutch. This settlement was restored to the Province of New York when New York was recaptured from the Dutch in November, 1674.[citation needed]

Government

[edit]The Lords Baltimore

[edit]

- George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (1579–1631), Secretary of State under King James I, applied in 1629 for a charter to establish a colony in the Mid-Atlantic area of North America, but died five weeks before it was issued.[29]

- Caecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore (1605–1675), inherited both his father's title and his charter, which was granted in 1632. He was named for Sir Robert Cecil, first Earl of Salisbury,[30] principal Secretary of State to Queen Elizabeth, whom Calvert had met during an extended trip to Europe between 1601 and 1603.[29] Rather than go to the colony himself, Baltimore stayed behind in England to deal with the political opposition raised by supporters of the Virginia Colony and sent his next younger brother Leonard in his stead. Caecilius never travelled to Maryland.[31]

- Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore (1637–1715), sailed to Maryland in 1661 as a young man of 24, becoming the first member of the Calvert family to take personal charge of the colony. He was appointed deputy governor by his father and, when the 2nd Lord Baltimore died in 1675, Charles inherited Maryland, becoming governor in his own right. During his tenure the price of tobacco began to decline, causing economic hardship especially among the poor. A hurricane in 1667 devastated the tobacco crop.[32] In 1684, the 3rd Lord Baltimore traveled to England[33] in regard to a border dispute with William Penn. He never returned to Maryland. In his absence the Protestant Revolution of 1689 took control of the colony. That year the family's royal charter was also withdrawn, and Maryland became a Royal Colony.

- Benedict Calvert, 4th Baron Baltimore (1679–1715) understood that the chief impediment to the restoration of his family's title to Maryland was the question of religion.[34] In 1713 he converted to Anglicanism, despite his father cutting off his support. He also withdrew his son Charles from a Jesuit school, largely for political reasons. Henceforth father and son would worship within the Church of England, much to the disgust of his father Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore, who maintained his Catholic faith despite the political drawbacks, until his death in February 1715.[34] Benedict became the Fourth Lord Baltimore upon his father's death in February 1715 and immediately petitioned King George I to reinstate the family's charter. However, the 4th Lord Baltimore survived his father by only two months, dying himself in April 1715.

- Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore (1699–1751) was the great-grandson of Charles II of England through his maternal grandmother, Charlotte Lee, Countess of Lichfield, the illegitimate daughter of the king's mistress, Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland. The Province of Maryland was restored to the control of the Calvert family by King George I when around 1715 Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, swore publicly that he was a Protestant and had embraced the Anglican faith.

- Frederick Calvert, 6th Baron Baltimore (1731–1771) inherited from his father the title Baron Baltimore and the Proprietary Governorship of the Province of Maryland in 1751. The 6th Lord Baltimore wielded immense power in Maryland, which was then a colony of the Kingdom of Great Britain, administered directly by the Calverts.[36] Frederick's inheritance coincided with a period of rising discontent in Maryland, amid growing demands by the legislative assembly for an end to his family's authoritarian rule. Frederick, however, remained aloof from the colony and never set foot in it in his lifetime. He lived a life of leisure, writing verse and regarding the Province of Maryland as little more than a source of revenue. The colony was ruled through governors appointed by the 6th Lord Baltimore. His frequent travels made him difficult to contact and meant that Maryland was largely ruled without him. His personal life was extremely scandalous by the standards of the time, and this contributed to growing unrest in his colony. In 1758, his wife "died from a hurt she received by a fall out of a Phaeton carriage" while accompanied by her husband. Although Frederick was suspected of foul play, no charges were ever brought.[35]

Frederick died in 1771, by which time relations between Britain and her American colonies were fast deteriorating. In his will, Frederick left his proprietary Palatinate of Maryland to his eldest illegitimate son, Henry Harford, then aged just 13. The colony, perhaps grateful to be rid of Frederick at last, recognized Harford as Calvert's heir. However, the will was challenged by the family of Frederick's sister, Louisa Calvert Browning, who did not recognize Harford's inheritance. Before the case could grind its way through the Court of Chancery, Maryland had become engulfed by the American Revolution and by 1776 was at war with Britain. Henry Harford would ultimately lose almost all his colonial possessions.

Proprietarial rule

[edit]Lord Baltimore held all the land directly from the King for the payment of "two Indian arrowheads annually and one fifth of all gold and silver found in the colony."[1] Maryland's foundation charter was drafted in feudal terms and based on the practices of the ancient County Palatine of Durham, which existed until 1646. He was given the rights and privileges of a Palatine lord, and the extensive authority that went with it. The Proprietor had the right and power to establish courts and appoint judges and magistrates, to enforce all laws, to grant titles, to erect towns, to pardon all offenses, to found churches, to call out the fighting population and wage war, to impose martial law, to convey or lease the land, and to levy duties and tolls.[1]

However, as elsewhere in English North America, English political institutions were re-created in the colonies, and the Maryland General Assembly fulfilled much the same function as the House of Commons of England.[37] An act was passed providing that:

- "from henceforth and for ever everyone being of the council of the Province and any other gentleman of able judgement summoned by writ (and the Lord of every Manor within this Province after Manors be erected) shall and may have his voice, seat, and place in every General Assembly. together with two or more able and sufficient men for the hundred as the said freedmen or the major part of them ... shall think good".

In addition, the Lord Proprietor could summon any delegates whom he was pleased to select.[38]

In some ways the General Assembly was an improvement upon the institutions of the mother country. In 1639, noting that Parliament had not been summoned in England for a decade, the free men of Maryland passed an act to the effect that "assemblies were to be called once in every three years at the least," ensuring that their voices would be regularly heard.[37]

Due to immigration, by 1660 the population of the Province had gradually become predominantly Protestant. Political power remained concentrated in the hands of the largely Catholic elite. Most councilors were Catholics and many were related by blood or marriage to the Calverts, enjoying political patronage and often lucrative offices such as commands in the militia or sinecures in the Land Office.[39]

Religious conflict

[edit]

Although Maryland was an early pioneer of religious toleration in the British colonies, religious strife among Anglicans, Puritans, Catholics, and Quakers was common in the early years, and Puritan rebels briefly seized control of the province. In 1644 the dispute with William Claiborne led to armed conflict. Claiborne seized Kent Island while his associate, the pro-Parliament Puritan Richard Ingle, took over St. Mary's.[22] Both used religion as a tool to gain popular support. From 1644 to 1646, the so-called "Plundering Time" was a period of civil unrest aggravated by the tensions of the English Civil War (1641–1651). Leonard Calvert returned from exile with troops, recaptured St. Mary's City, and eventually restored order.[11]

In 1649 Maryland passed the Maryland Toleration Act, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, a law mandating religious tolerance for trinitarian Christians. Passed on September 21, 1649, by the assembly of the Maryland Colony, it was the first law requiring religious tolerance in the English North American colonies. In 1654, after the Third English Civil War (1649–1651), Parliamentary (Puritan) forces assumed control of Maryland for a time.

When dissidents pressed for an established church, Caecilius Calvert's noted that Maryland settlers were "Presbyterians, Independents, Anabaptists, and Quakers, those of the Church of England as well as the Romish being the fewest ... it would be a most difficult task to draw such persons to consent unto a Law which shall compel them to maintaine ministers of a contrary perswasion to themselves."[39]

In 1650, Maryland had 10 churches with regular services which included all 5 Catholic churches in the colonies at the time, 4 Anglican churches, and 1 Congregational church.[40] Following the First Great Awakening (1730–1755), the number of regular places of worship in Maryland grew to 94 in 1750 (50 Anglican, 18 Presbyterian, 15 Catholic, 4 Baptist, 4 Dutch Reformed, and 3 Lutheran),[41] with the colony gaining an additional 110 regular places of worship to a total of 204 by 1776 (51 Episcopal, 30 Catholic, 29 Presbyterian, 26 Friends, 21 Methodism, 16 German Reformed, 16 Lutheran, 5 Baptist, 5 German Baptist Brethren, 2 Dutch Reformed, 2 Moravian, and 1 Mennonite).[42]

The Protestant Revolution of 1689

[edit]

In 1689, Maryland Puritans, by now a substantial majority in the colony, revolted against the proprietary government, in part because of the apparent preferment of Catholics like Colonel Henry Darnall to official positions of power. Led by Colonel John Coode, an army of 700 Puritans defeated a proprietarial army led by Colonel Darnall.[43] Darnall later wrote: "Wee being in this condition and no hope left of quieting the people thus enraged, to prevent effusion of blood, capitulated and surrendered." The victorious Coode and his Puritans set up a new government that outlawed Catholicism, and Darnall was deprived of all his official roles.[43] Coode's government was, however, unpopular; and William III installed a Crown-appointed governor in 1692. This was Lionel Copley who governed Maryland until his death in 1694 and was replaced by Francis Nicholson.[44]

After this "Protestant Revolution" in Maryland, Darnall was forced, like many other Catholics, to maintain a secret chapel in his home in order to celebrate the Catholic Mass. In 1704, an Act was passed "to prevent the growth of Popery in this Province", preventing Catholics from holding political office.[43]

Full religious toleration would not be restored in Maryland until the American Revolution, when Darnall's great-grandson Charles Carroll of Carrollton, arguably the wealthiest Catholic in Maryland, signed the American Declaration of Independence.[citation needed]

Plantations and economy

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1640 | 583 | — |

| 1650 | 4,504 | +672.6% |

| 1660 | 8,426 | +87.1% |

| 1670 | 13,226 | +57.0% |

| 1680 | 17,904 | +35.4% |

| 1690 | 24,024 | +34.2% |

| 1700 | 29,604 | +23.2% |

| 1710 | 42,741 | +44.4% |

| 1720 | 66,133 | +54.7% |

| 1730 | 91,113 | +37.8% |

| 1740 | 116,093 | +27.4% |

| 1750 | 141,073 | +21.5% |

| 1760 | 162,267 | +15.0% |

| 1770 | 202,599 | +24.9% |

| 1780 | 245,474 | +21.2% |

| Source: 1640–1760;[45] 1770–1780[46] | ||

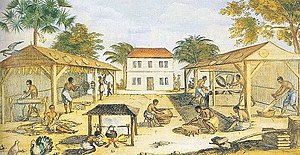

Early settlements and population centers tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into Chesapeake Bay. In the 17th century, most Marylanders lived in rough conditions on small farms. While they raised a variety of fruits, vegetables, grains, and livestock, the main cash crop was tobacco, which soon dominated the province's economy.

The Province of Maryland developed along lines very similar to those of Virginia. Tobacco was used as money, and the colonial legislature was obliged to pass a law requiring tobacco planters to raise a certain amount of corn as well, in order to ensure that the colonists would not go hungry. Like Virginia, Maryland's economy quickly became centered around the farming of tobacco for sale in Europe. The need for cheap labor to help with the growth of tobacco, and later with the mixed farming economy that developed when tobacco prices collapsed, led to a rapid expansion of indentured servitude and, later, forcible immigration and enslavement of Africans.

By 1730 there were public tobacco warehouses every fourteen miles. Bonded at £1,000 sterling, each inspector received from £25 to £60 as annual salary. Four hogsheads of 950 pounds were considered a ton for London shipment. Ships from English ports did not need port cities; they called at the wharves of warehouses or plantations along the rivers for tobacco and the next year returned with goods the planters had ordered from the shops of London.[47][48]

Outside the plantations, much land was operated by independent farmers who rented from the proprietors, or owned it outright. They emphasized subsistence farming to grow food for their large families. Many of the Irish and Scottish immigrants specialized in rye-whiskey making, which they sold to obtain cash.[49]

The 18th century

[edit]

Maryland developed into a plantation colony by the 18th century. In 1700 there were about 25,000 people and by 1750 that had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black.[50] Maryland planters also made extensive use of indentured servants and penal labor. An extensive system of rivers facilitated the movement of produce from inland plantations and farms to the Atlantic coast for export. Baltimore, on the Patapsco River, leading to the Chesapeake Bay, was the second-most important port in the 18th-century South, after Charleston, South Carolina.

Dr. Alexander Hamilton (1712–1756) was a Scottish-born doctor and writer who lived and worked in Annapolis. Leo Lemay says his 1744 travel diary Gentleman's Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton is "the best single portrait of men and manners, of rural and urban life, of the wide range of society and scenery in colonial America."[51]

The Abbé Claude C. Robin, a chaplain in the army of General Rochambeau,[52] who travelled through Maryland during the Revolutionary War, described the lifestyle enjoyed by families of wealth and status in the colony:

- [Maryland houses] are large and spacious habitations, widely separated, composed of a number of buildings and surrounded by plantations extending farther than the eye can reach, cultivated ... by unhappy black men whom European avarice brings hither. ...Their furniture is of the most costly wood, and rarest marbles, enriched by skilful and artistic work. Their elegant and light carriages are drawn by finely bred horses, and driven by richly apparelled slaves."[53]

The first printing press was introduced to the Province of Maryland in 1765 by a German immigrant, Nicholas Hasselbach, whose equipment was later used in the printing of Baltimore's first newspapers, The Maryland Journal and The Baltimore Advertiser, first published by William Goddard in 1773.[54][55][56]

In the late colonial period, the southern and eastern portions of the Province continued in their tobacco economy, but as the American Revolution approached, northern and central Maryland increasingly became centers of wheat production. This helped drive the expansion of interior farming towns like Frederick and Maryland's major port city of Baltimore.[57]

The American Revolution

[edit]Up to the time of the American Revolution, the Province of Maryland was one of two colonies that remained an English proprietary colony, Pennsylvania being the other.[58] Maryland declared independence from Britain in 1776, with Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton signing the Declaration of Independence for the colony. In the 1776–77 debates over the Articles of Confederation, Maryland delegates led the party that insisted that states with western land claims cede them to the Confederation government, and in 1781 Maryland became the last state to ratify the Articles of Confederation. It accepted the United States Constitution more readily, ratifying it on April 28, 1788.

Maryland also gave up some territory to create the new District of Columbia after the American Revolution.

See also

[edit]- List of colonial governors of Maryland

- Colonial families of Maryland

- History of Maryland

- History of slavery in Maryland

- Thomas Cresap

- Lord Baltimore penny

- Economic history of Colonial Maryland

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Charter of Maryland : 1632". avalon.law.yale.edu. December 18, 1998.

- ^ Sudie Doggett Wike (2022). German Footprints in America, Four Centuries of Immigration and Cultural Influence. McFarland Incorporated Publishers. p. 155.

- ^ Clayton Colman Hall (1902). The Lords Baltimore and the Maryland Palatinate, Six Lectures on Maryland Colonial History Delivered Before the Johns Hopkins University in the Year 1902. J. Murphy Company. p. 55.

- ^ Frederick Robertson Jones (1904). The Colonization of the Middle States and Maryland. p. 205.

- ^ Butler, James Davie (1896). "British Convicts Shipped to American Colonies". The American Historical Review. 2 (1): 12–33. doi:10.2307/1833611. JSTOR 1833611.

- ^ Sparks, Jared (1846). The Library of American Biography: George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown. pp. 16–.

Leonard Calvert.

- ^ "Maryland's Name & Queen Henrietta Maria". Mdarchives.state.md.us.

- ^ Frances Copeland Stickles, A Crown for Henrietta Maria: Maryland's Namesake Queen (1988), p. 4

- ^ a b Dozer, Donald Marquand. Portrait of The Free State: A History of Maryland. Tidewater Publishers. 1976. ISBN 0-87033-226-0.

- ^ Taylor, Alan. American Colonies (New York: Viking, 2001), p. 136; and, John Mack Faragher, ed., The Encyclopedia of Colonial and Revolutionary America (New York: Facts on File, 1990), p. 254.

- ^ a b c Knott, Aloysius. "Maryland." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910

- ^ "MD History Q&A | Maryland Historical Society". www.mdhs.org. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ Elson, Henry William. "Colonial Maryland". www.usahistory.info. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ "Maryland — The Catholic Experiment [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org.

- ^ a b c Jennings, Francis (1968). "Glory, Death, and Transfiguration: The Susquehannock Indians in the Seventeenth Century". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 112 (1): 15–53. JSTOR 986100.

- ^ Samford, Patricia (February 11, 2015). "1652 Susquehannock Treaty". Maryland History by the Object. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Shen, Fern. "A 1652 Treaty Opens up the Story of the First Baltimoreans". Baltimore Brew. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Rice, James Douglas. "Bacon's Rebellion (1676–1677)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ Kruer, Matthew (2021). Time of Anarchy: Indigenous Power and the Crisis of Colonialism in Early America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97617-7.

- ^ "Religion and the Founding of the American Republic: America as a Religious Refuge: The Seventeenth Century, Part 2". loc.gov. Library of Congress. June 1998. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ Stewart, George R. (1967) [1945]. Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States (Sentry edition (3rd) ed.). Houghton Mifflin. pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c Brenner, Robert (2003). Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London's Overseas Traders London:Verso. p. 124, ISBN 1-85984-333-6

- ^ Browne, William Hand (1890). George Calvert and Cecil Calvert. Dodd, Mead. pp. 63–67.

- ^ Pestana, Carla. "The English Civil Wars and Virginia." Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 4 May. 2012. Accessed October 13, 2018, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/English_Civil_Wars_and_Virginia_The.

- ^ Fiske, John (1900). Old Virginia and Her Neighbours. Houghton, Mifflin and company. p. 294. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ "Virginia-Maryland Boundary", Virginia Places, accessed October 13, 2018

- ^ Hubbard, Bill Jr. (2009). American Boundaries: the Nation, the States, the Rectangular Survey. University of Chicago Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-0-226-35591-7.

- ^ Edward Danson, Drawing the Line: How Mason and Dixon Surveyed the Most Famous Border in America (2000)

- ^ a b Browne, William Hand (1890). George Calvert and Cecil Calvert: Barons Baltimore of Baltimore. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company.

- ^ Browne, p. 4.

- ^ Browne, p. 39

- ^ Brugger, Robert J. (September 25, 1996). Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5465-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll Saga, 1500-1782 Hoffman, Ronald, Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll Saga, 1500–1782 Retrieved Jan 24 2010

- ^ a b Hoffman, Ronald, p.79, Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll Saga, 1500–1782 Retrieved August 9, 2010

- ^ a b "Frederick Calvert". Epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk.

- ^ "Frederick Calvert". Aboutfamouspeople.com.

- ^ a b Andrews, p. 70

- ^ Andrews, p. 71

- ^ a b Brugger, Robert J., p. 38, Maryland, a Middle Temperament 1634–1980 Retrieved July 26, 2010

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. p. 179. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. p. 181. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1995). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Revolutionary America 1763 to 1800. New York: Facts on File. p. 198. ISBN 978-0816025282.

- ^ a b c Roark, Elisabeth Louise, p. 78, Artists of colonial America Retrieved February 22, 2010

- ^ John E. Findling, Frank W. Thackeray, Events that Changed America Through the Seventeenth Century, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- ^ "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 1168.

- ^ Gloria L. Main, Tobacco Colony: Life in Early Maryland, 1650–1720 (1982).

- ^ C. A. Werner, Tobaccoland A Book About Tobacco; Its History, Legends, Literature, Cultivation, Social and Hygienic Influences (1922)

- ^ Gregory A. Stiverson, Poverty in a Land of Plenty: Tenancy in Eighteenth-Century Maryland (Johns Hopkins U. Press, 1978)

- ^ John Mack Faragher, ed., The Encyclopedia of Colonial and Revolutionary America (New York: Facts on File, 1990), p. 257

- ^ J.A. Leo Lemay, Men of Letters in Colonial Maryland (1972) p 229.

- ^ Kimball, Gertrude Selwyn (1899). Pictures of Rhode Island in the Past, 1642-1833. Providence, R, I.: Preston and Rounds. p. 95. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Yentsch, Anne E, p. 265, A Chesapeake Family and their Slaves: a Study in Historical Archaeology, Cambridge University Press (1994) Retrieved Jan 2010

- ^ Thomas, 1874, p. 323

- ^ Wroth, 1938, p. 41

- ^ Wroth, 1922, p. 114

- ^ Marks, Bayly Ellen (1982). "Rural Response to Urban Penetration: Baltimore and St. Mary's County, Maryland, 1790–1840". Journal of Historical Geography. 8 (2): 113–27. doi:10.1016/0305-7488(82)90001-9.

- ^ America's Founding Charters: Primary Documents of Colonial and Revolutionary Era Governance, Volume 1 by Jon. L. Wakelyn. 2006. p. 109.

Sources

[edit]- Andrews, Matthew Page, History of Maryland, Doubleday, New York (1929)

- Everstine, Carl N. "The Establishment of Legislative Power in Maryland", 12 Maryland Law Review 99 (1951)

- Thomas, Isaiah (1874). The history of printing in America, with a biography of printers. Vol. I. New York, B. Franklin.

- Wroth, Lawrence C. (1922). A History of Printing in Colonial Maryland, 1686–1776. Baltimore : Typothetae of Baltimore.

- Wroth, Lawrence C. (1938). The Colonial Printer. Portland, Me., The Southworth-Anthoensen press.

External links

[edit]- 1632 establishments in the British Empire

- 1776 disestablishments in the British Empire

- Pre-statehood history of Maryland

- Thirteen Colonies

- Former English colonies

- States and territories established in 1632

- States and territories disestablished in 1776

- Province of Maryland

- Colonial United States (British)

- Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas

- Henrietta Maria of France