Colorectal cancer

| Colorectal cancer | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

Colorectal cancer, commonly known as bowel cancer, is a cancer from uncontrolled cell growth in the colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine), or in the appendix. Symptoms typically include rectal bleeding and anemia which are sometimes associated with weight loss and changes in bowel habits.

Most colorectal cancer occurs due to lifestyle and increasing age with only a minority of cases associated with underlying genetic disorders. It typically starts in the lining of the bowel and if left untreated, can grow into the muscle layers underneath, and then through the bowel wall. Screening is effective at decreasing the chance of dying from colorectal cancer and is recommended starting at the age of 50 and continuing until a person is 75 years old. Localized bowel cancer is usually diagnosed through sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

Cancers that are confined within the wall of the colon are often curable with surgery while cancer that has spread widely around the body is usually not curable and management then focuses on extending the person's life via chemotherapy and improving quality of life. Colorectal cancer is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world, but it is more common in developed countries.[1] Around 60% of cases were diagnosed in the developed world.[1] It is estimated that worldwide, in 2008, 1.23 million new cases of colorectal cancer were clinically diagnosed, and that it killed 608,000 people.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms and signs of colorectal cancer depend on the location of tumor in the bowel, and whether it has spread elsewhere in the body (metastasis). The classic warning signs include: worsening constipation, blood in the stool, weight loss, fever, loss of appetite, and nausea or vomiting in someone over 50 years old.[2] While rectal bleeding or anemia are high-risk features in those over the age of 50,[3] other commonly described symptoms including weight loss and change in bowel habit are typically only concerning if associated with bleeding.[3][4]

Cause

Greater than 75-95% of colon cancer occurs in people with little or no genetic risk.[5][6] While some risk factors such as older age and male gender cannot be changed many can.[6] A high fat, alcohol or red meat intake are risk factors for colorectal cancer as is obesity, smoking and a lack of physical exercise.[5] The risk for alcohol appears to increase at greater than one drink per day.[7]

Inflammatory bowel disease

People with inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease) are at increased risk of colon cancer.[8] The risk is greater the longer a person has had the disease,[9] and the worse the severity of inflammation.[10] In these high risk groups both prevention with aspirin and regular colonoscopies are recommended.[9] People with inflammatory bowel disease account for less than 2% of colon cancer cases yearly.[10] In those with Crohn's disease 2% get colorectal cancer after 10 years, 8% after 20 years, and 18% after 30 years.[10] In those with ulcerative colitis approximately 20% develop tumors within the first 10 years.[10]

Genetics

Those with a family history in two or more first degree relatives have a two to threefold greater risk of disease and this group accounts for about 20% of all cases.[6] A number of genetic syndromes are also associated with higher rates of colorectal cancer. The most common of these is hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome) which is present in about 3% of people with colorectal cancer.[6] Other syndromes that are strongly associated include: Gardner syndrome,[11] and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) in which cancer nearly always occurs and is the cause of 1% of cases.[12]

Pathogenesis

Colorectal cancer is a disease originating from the epithelial cells lining the colon or rectum of the gastrointestinal tract, most frequently as a result of mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway that artificially increase signaling activity. The mutations can be inherited or are acquired, and must probably occur in the intestinal crypt stem cell.[13][14] The most commonly mutated gene in all colorectal cancer is the APC gene, which produces the APC protein. The APC protein is a "brake" on the accumulation of β-catenin protein; without APC, β-catenin accumulates to high levels and translocates (moves) into the nucleus, binds to DNA, and activates the transcription of genes that are normally important for stem cell renewal and differentiation but when inappropriately expressed at high levels can cause cancer. While APC is mutated in most colon cancers, some cancers have increased β-catenin because of mutations in β-catenin (CTNNB1) that block its degradation, or they have mutation(s) in other genes with function analogous to APC such as AXIN1, AXIN2, TCF7L2, or NKD1.[15]

Beyond the defects in the Wnt-APC-beta-catenin signaling pathway, other mutations must occur for the cell to become cancerous. The p53 protein, produced by the TP53 gene, normally monitors cell division and kills cells if they have Wnt pathway defects. Eventually, a cell line acquires a mutation in the TP53 gene and transforms the tissue from an adenoma into an invasive carcinoma. (Sometimes the gene encoding p53 is not mutated, but another protective protein named BAX is.)[15]

Other apoptotic proteins commonly deactivated in colorectal cancers are TGF-β and DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer). TGF-β has a deactivating mutation in at least half of colorectal cancers. Sometimes TGF-β is not deactivated, but a downstream protein named SMAD is.[15] DCC commonly has deletion of its chromosome segment in colorectal cancer.[16]

Some genes are oncogenes - they are overexpressed in colorectal cancer. For example, genes encoding the proteins KRAS, RAF,[disambiguation needed] and PI3K, which normally stimulate the cell to divide in response to growth factors, can acquire mutations that result in over-activation of cell proliferation. The chronological order of mutations is sometimes important, with a primary KRAS mutation generally leading to a self-limiting hyperplastic or borderline lesion, but if occurring after a previous APC mutation it often progresses to cancer.[17] PTEN, a tumor suppressor, normally inhibits PI3K, but can sometimes become mutated and deactivated.[15]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of colorectal cancer is via tumor biopsy typically done during sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.[6] The extent of the disease is then usually determined by a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis.[6] There are other potential imaging test such as PET and MRI which may be used in certain cases.[6] Colon cancer staging is done next and based on the TNM system which is determined by how much the initial tumor has spread, if and where lymph nodes are involved, and if and how many metastases there are.[6]

Pathology

The pathology of the tumor is usually reported from the analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. A pathology report will usually contain a description of cell type and grade. The most common colon cancer cell type is adenocarcinoma which accounts for 95% of cases. Other, rarer types include lymphoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancers on the right side (ascending colon and cecum) tend to be exophytic, that is, the tumour grows outwards from one location in the bowel wall. This very rarely causes obstruction of feces, and presents with symptoms such as anemia. Left-sided tumours tend to be circumferential, and can obstruct the bowel much like a napkin ring.

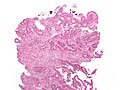

Adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from glandular epithelium of the colorectal mucosa. It invades the wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae, the submucosa and thence the muscularis propria. Tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Sometimes, tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus, which invades the interstitium producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces) - mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus at the periphery - "signet-ring cell." Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism, and mucosecretion of the predominant pattern, adenocarcinoma may present three degrees of differentiation: well, moderately, and poorly differentiated.[18]

Most colorectal cancer tumors are thought to be cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) positive. This enzyme is generally not found in healthy colon tissue, but is thought to fuel abnormal cell growth.

-

Gross appearance of a colectomy specimen containing two adenomatous polyps (the brownish oval tumors above the labels, attached to the normal beige lining by a stalk) and one invasive colorectal carcinoma (the crater-like, reddish, irregularly shaped tumor located above the label).

-

Endoscopic image of colon cancer identified in sigmoid colon on screening colonoscopy in the setting of Crohn's disease.

-

Micrograph of an invasive adenocarcinoma (the most common type of colorectal cancer). The cancerous cells are seen in the center and at the bottom right of the image (blue). Near normal colon-lining cells are seen at the top right of the image.

-

Histopathologic image of colonic carcinoid stained by hematoxylin and eosin.

-

Micrograph of a tubular adenoma (left of image), a type of colonic polyp and a precursor of colorectal cancer. Normal colorectal mucosa is seen on the right. H&E stain.

-

PET/CT of a staging exam of colon carcinoma. Besides the primary tumor a lot of lesions can be seen. On cursor position: lung nodule.

Prevention

Most colorectal cancers should be preventable, through increased surveillance, improved lifestyle, and, probably, the use of dietary chemopreventative agents.

Lifestyle

Current dietary recommendations to prevent colorectal cancer include increasing the consumption of whole grains, fruits and vegetables, and reducing the intake of red meat.[19][20] The evidence for fiber and fruits and vegetables however is poor.[20] Physical activity can moderately reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.[21]

Medication

Aspirin and celecoxib appear to decrease the risk of colorectal cancer in those at high risk.[22] However it is not recommended in those at average risk.[23] There is tentative evidence for calcium supplementation but it is not sufficient to make a recommendation.[24] Vitamin D intake and blood levels are associated with a lower risk of colon cancer.[25][26]

Screening

More than 80% colorectal cancers arise from adenomatous polyps making this cancer amenable to screening. The three main screening tests are fecal occult blood testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy. Fecal occult blood testing of the stool is typically recommended every two years and can be either guaiac based or immunochemical. In the United States screening is recommended between the age of 50 and 75 years with sigmoidoscopy every 5 years and colonoscopy every 10 years.[27] For those at high risk, screenings usually begin at around 40.[28] Virtual colonoscopy via a CT scan aspears as good as standard colonoscopy but is expensive and associated with radiation exposure.[6] It is believed that screening has the potential to reduce colorectal cancer deaths by 60%.[29] For people over 75 or those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years screening is not recommended.[30]

Management

The treatment of colorectal cancer depends on how advanced it is.[31] When colorectal cancer is caught early surgery can be curative.[6] However, when it is detected at later stages (metastases are present), this is less likely and treatment is often directed more at extending life and keeping people comfortable.[6]

Surgery

For people with localized cancer the preferred treatment is complete surgical removal with the attempt of achieving a cure. This can either be done by an open laparotomy or sometimes laparoscopically. If there are only a few metastases in the liver or lungs they may also be removed. Sometimes chemotherapy is used before surgery to shrink the cancer before attempting to remove it. The two most common sites of recurrence if it occurs is in the liver and lungs.[6]

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy may be used in addition to surgery in certain cases[6] as adjuvant therapy. If cancer has entered the lymph nodes adding the chemotherapy agents fluorouracil, or capecitabine increases life expectancy. If the lymph nodes do not contain cancer the benefits of chemotherapy are controversial. If the cancer is widely metastatic or unresectable, treatment is then palliative. Typically in this case a couple of different chemotherapy medications are used.[6] Chemotherapy drugs may include combinations of agents including fluorouracil, capecitabine, UFT, leucovorin, irinotecan, or oxaliplatin.[32]

Radiation

While a combination of radiation and chemotherapy may be useful for rectal cancer,[6] its use in colon cancer is not routine due to the sensitivity of the bowels to radiation.[33]

Palliative care

In people with incurable colorectal cancer, palliative care can be considered for improving quality of life. Surgical options may include non-curative surgical removal of some of the cancer tissue, bypassing part of the intestines, or stent placement. These procedures can be considered to improve symptoms and reduce complications such as bleeding from the tumor, abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction.[34] Non-operative methods of symptomatic treatment include radiation therapy to decrease tumor size as well as pain medications.[35]

Prognosis

In Europe the 5 year survival for colorectal cancer is less than 60%.[6] In the developed world about a third of people who get the disease die from it.[6]

Survival is directly related to detection and the type of cancer involved, but overall is poor for symptomatic cancers, as they are typically quite advanced. Survival rates for early stage detection is about 5 times that of late stage cancers. For example, patients with a tumor that has not breached the muscularis mucosa (TNM stage Tis, N0, M0) have an average 5-year survival of 100%, while those with an invasive cancer, i.e. T1 (within the submucosal layer) or T2 (within the muscular layer) cancer have an average 5-year survival of approximately 90%. Those with a more invasive tumor, yet without node involvement (T3-4, N0, M0) have an average 5-year survival of approximately 70%. Patients with positive regional lymph nodes (any T, N1-3, M0) have an average 5-year survival of approximately 40%, while those with distant metastases (any T, any N, M1) have an average 5-year survival of approximately 5%.[36]

According to the American Cancer Society statistics in 2006,[37] over 20% of patients present with metastatic (stage IV) colorectal cancer at the time of diagnosis, and up to 25% of this group will have isolated liver metastasis that is potentially resectable. Lesions which undergo curative resection have demonstrated 5-year survival outcomes now exceeding 50%.[38]

Follow-up

The aims of follow-up are to diagnose, in the earliest possible stage, any metastasis or tumors that develop later, but did not originate from the original cancer (metachronous lesions).

The U.S. National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology provide guidelines for the follow-up of colon cancer.[39][40] A medical history and physical examination are recommended every 3 to 6 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 5 years. Carcinoembryonic antigen blood level measurements follow the same timing, but are only advised for patients with T2 or greater lesions who are candidates for intervention. A CT-scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis can be considered annually for the first 3 years for patients who are at high risk of recurrence (for example, patients who had poorly differentiated tumors or venous or lymphatic invasion) and are candidates for curative surgery (with the aim to cure). A colonoscopy can be done after 1 year, except if it could not be done during the initial staging because of an obstructing mass, in which case it should be performed after 3 to 6 months. If a villous polyp, a polyp >1 centimeter or high grade dysplasia is found, it can be repeated after 3 years, then every 5 years. For other abnormalities, the colonoscopy can be repeated after 1 year.

Routine PET or ultrasound scanning, chest X-rays, complete blood count or liver function tests are not recommended.[39][40] These guidelines are based on recent meta-analyses showing intensive surveillance and close follow-up can reduce the 5-year mortality rate from 37% to 30%.[41][42][43]

Epidemiology

Globally greater than 1 million people get colorectal cancer yearly[6] resulting in about 0.5 million deaths.[45] As of 2008 it is the second most common cause of cancer in women and the third most common in men[46] with it being the fourth most common cause of cancer death after lung, stomach, and liver cancer.[47] It is more common in developed than developing countries.[45]

Society and culture

In the United States March is colorectal cancer awareness month.[29]

Notable cases

- Corazon Aquino, former president of the Philippines[48]

- Pope John Paul II[49]

- Ronald Reagan[50]

- Harold Wilson, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[51]

- Robin Gibb, musician and member of the Bee Gees[52]

Research

References

- ^ a b c http://globocan.iarc.fr/

- ^ al.], edited by Tadataka Yamada ; associate editors, David H. Alpers ... [et (2008). Principles of clinical gastroenterology. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 381. ISBN 978-1-4051-6910-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Astin, M (2011 May). "The diagnostic value of symptoms for colorectal cancer in primary care: a systematic review". The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 61 (586): 231–43. doi:10.3399/bjgp11X572427. PMC 3080228. PMID 21619747.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Adelstein, BA (2011-05-30). "Most bowel cancer symptoms do not indicate colorectal cancer and polyps: a systematic review". BMC gastroenterology. 11: 65. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-11-65. PMC 3120795. PMID 21624112.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Watson, AJ (2011). "Colon cancer: a civilization disorder". Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 29 (2): 222–8. doi:10.1159/000323926. PMID 21734388.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Cunningham, D (2010-03-20). "Colorectal cancer" (PDF). Lancet. 375 (9719): 1030–47. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. PMID 20304247.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fedirko, V (2011 Sep). "Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies". Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 22 (9): 1958–72. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq653. PMID 21307158.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jawad, N (2011). "Inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer". Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 185: 99–115. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03503-6_6. PMID 21822822.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Xie, J (2008-01-21). "Cancer in inflammatory bowel disease". World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 14 (3): 378–89. PMC 2679126. PMID 18200660.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Triantafillidis, JK (2009 Jul). "Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, risk factors, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention strategies". Anticancer research. 29 (7): 2727–37. PMID 19596953.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Juhn, E (2010). "Gardner syndrome: skin manifestations, differential diagnosis and management". American journal of clinical dermatology. 11 (2): 117–22. doi:10.2165/11311180-000000000-00000. PMID 20141232.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Half, E (2009-10-12). "Familial adenomatous polyposis". Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 4: 22. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-4-22. PMC 2772987. PMID 19822006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ionov Y, Peinado MA, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M (1993). "Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis". Nature. 363 (6429): 558–61. doi:10.1038/363558a0. PMID 8505985.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Srikumar Chakravarthi, Baba Krishnan, Malathy Madhavan (1999). "Apoptosis and expression of p53 in colorectal neoplasms". Indian J Med Res. 86 (7): 95–102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM (2009). "Molecular Origins of Cancer: Molecular Basis of Colorectal Cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (25): 2449–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804588. PMC 2843693. PMID 20018966.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mehlen P, Fearon ER (2004). "Role of the dependence receptor DCC in colorectal cancer pathogenesis". J. Clin. Oncol. 22 (16): 3420–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.02.019. PMID 15310786.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15286780, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15286780instead. - ^ Pathology atlas

- ^ Campos, FG (2005 Jan-Feb). "Diet and colorectal cancer: current evidence for etiology and prevention". Nutricion hospitalaria : organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Nutricion Parenteral y Enteral. 20 (1): 18–25. PMID 15762416.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Doyle, VC (2007 May-Jun). "Nutrition and colorectal cancer risk: a literature review". Gastroenterology nursing : the official journal of the Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates. 30 (3): 178–82, quiz 182-3. doi:10.1097/01.SGA.0000278165.05435.c0. PMID 17568255.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Harriss, DJ (2009 Sep). "Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (2): a systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with leisure-time physical activity". Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 11 (7): 689–701. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01767.x. PMID 19207713.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cooper, K (2010 Jun). "Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer: systematic review and economic evaluation". Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 14 (32): 1–206. doi:10.3310/hta14320. PMID 20594533.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2010/2011). "Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for the Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer". United States Department of Health & Human Services.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Weingarten, MA (2008-01-23). "Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD003548. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003548.pub4. PMID 18254022.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ma, Y (2011-10-01). "Association between vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies". Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 29 (28): 3775–82. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7566. PMID 21876081.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Yin, L (2011 Jul-Aug). "Meta-analysis: Serum vitamin D and colorectal adenoma risk". Preventive medicine. 53 (1–2): 10–6. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.05.013. PMID 21672549.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Screening for Colorectal Cancer". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2008.

- ^ "Screening for Colorectal Cancer". U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2008.

- ^ a b He, J (2011). "Screening for colorectal cancer". Advances in surgery. 45: 31–44. PMID 21954677.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Qaseem, A (2012-03-06). "Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Guidance Statement From the American College of Physicians". Annals of internal medicine. 156 (5): 378–386. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00010. PMID 22393133.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stein, A (2011 Sep). "Current standards and new trends in the primary treatment of colorectal cancer". European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 47 Suppl 3: S312-4. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70183-6. PMID 21943995.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ none (2010 Oct). "Chemotherapy of metastatic colorectal cancer". Prescrire Int. 19 (109): 219–224. PMID 21180382.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ authors, editors, Vincent T. DeVita, Jr., Theodore S. Lawrence, Steven A. Rosenberg ; associate scientific advisors, Robert A. Weinberg, Ronald A. DePinho ; with 421 contributing (2008). DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's cancer : principles & practice of oncology (8th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1258. ISBN 978-0-7817-7207-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Wasserberg N, Kaufman HS (2007). "Palliation of colorectal cancer". Surg Oncol. 16 (4): 299–310. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2007.08.008. PMID 17913495.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Amersi F, Stamos MJ, Ko CY (2004). "Palliative care for colorectal cancer". Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 13 (3): 467–77. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2004.03.002. PMID 15236729.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Box 3-1, Page 107 in: Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7153-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.cancer.org/docroot/PRO/content/PRO_1_1_Cancer_Statistics_2006_Presentation.asp

- ^ Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, Garden OJ, Poston GJ, Rees M (2006). "Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: A systematic review of published studies". Br. J. Cancer. 94 (7): 982–99. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603033. PMC 2361241. PMID 16538219.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology - Colon Cancer (version 1, 2008: September 19, 2007).

- ^ a b Desch CE, Benson AB 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al.; American Society of Clinical Oncology (2005). "Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline" (PDF). J Clin Oncol. 23 (33): 8512–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. PMID 16260687.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN (2002). Jeffery, Mark (ed.). "Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD002200. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002200. PMID 11869629. CD002200.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Renehan AG, Egger M, Saunders MP, O'Dwyer ST (2002). "Impact on survival of intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials". BMJ. 324 (7341): 831–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7341.813. PMC 100789. PMID 11934773.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Figueredo A, Rumble RB, Maroun J, et al.; Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario's Program in Evidence-based Care. (2003). "Follow-up of patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer: a practice guideline". BMC Cancer. 3: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-3-26. PMC 270033. PMID 14529575.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Merika, E (2010 Sep-Oct). "Review. Colon cancer vaccines: an update". In vivo (Athens, Greece). 24 (5): 607–28. PMID 20952724.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jemal, A (2011-02-04). "Global cancer statistics". CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 61 (2): 69–90. doi:10.3322/caac.20107. PMID 21296855.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ WHO (2010). "Cancer". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/storypage.aspx?StoryID=112887

- ^ "Pope John Paul II". ABC News Online.

- ^ "Reagan turns 90". BBC News: Americas. 6 February 2001.

- ^ Daily Mail

- ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/04/23/colorectal-cancer_n_1446032.html