Gremlin

| Grouping | Mythological creature Fairy |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Mischievous spirit |

| Country | Western Hemisphere Europe (initially) |

A gremlin is an imaginary creature commonly depicted as mischievous and mechanically oriented, with a specific interest in aircraft. Gremlins' mischievous natures are similar to those of English folkloric imps, while their inclination to damage or dismantle machinery is more modern.

Aviation gremlin legend

Origins

Although their origin is found in myths among airmen, claiming that the gremlins were responsible for sabotaging aircraft, John W. Hazen states that "some people" derive the name from the Old English word gremian, "to vex."[1] Since the Second World War, different fantastical creatures have been referred to as gremlins, bearing varying degrees of resemblance to the originals.

The term "gremlin" denoting a mischievous creature that sabotages aircraft, originates in Royal Air Force (RAF) slang in the 1920s among the British pilots stationed in Malta, the Middle East and India, with the earliest recorded printed use being in a poem published in the journal Aeroplane, in Malta on April 10, 1929.[2][3] Later sources have sometimes claimed that the concept goes back to World War I, but there is no print evidence of this.[1][N 1]

An early reference to the Gremlin is in aviator Pauline Gower's The ATA: Women with Wings (1938) where Scotland is described as "gremlin country", a mystical and rugged territory where scissor-wielding gremlins cut the wires of biplanes when unsuspecting pilots were about.[4] An article by Hubert Griffith in the servicemen's fortnightly Royal Air Force Journal dated April 18, 1942, also chronicles the appearance of gremlins,[5] although the article states the stories had been in existence for several years, with later recollections of it having been told by Battle of Britain Spitfire pilots as early as 1940.[6]

This concept of gremlins was popularized during the Second World War among airmen of the UK's RAF units,[7] in particular the men of the high-altitude Photographic Reconnaissance Units (PRU) of RAF Benson, RAF Wick and RAF St Eval. The creatures were responsible for otherwise inexplicable accidents which sometimes occurred during their flights. Gremlins were also thought at one point to have enemy sympathies, but investigations revealed that enemy aircraft had similar and equally inexplicable mechanical problems. As such, gremlins were portrayed as being equal opportunity tricksters, taking no sides in the conflict, and acting out their mischief from their own self-interests.[8] In reality, the gremlins were a form of "buck passing" or deflecting blame.[8] This led the folklorist John Hazen to note, "Heretofore, the gremlin has been looked on as new phenomenon, a product of the machine age — the age of air."[1]

The Disney version

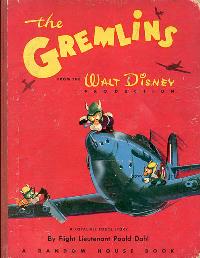

Author Roald Dahl is credited with getting the gremlins known outside the Royal Air Force.[9] He would have been familiar with the myth, having carried out his military service in 80 Squadron of the Royal Air Force in the Middle East. Dahl had his own experience in an accidental crash-landing in the Libyan Desert. In January, 1942 he was transferred to Washington, D.C. as Assistant Air attaché. There he wrote his first children's novel The Gremlins, in which he described male gremlins as "widgets" and females as "fifinellas". Dahl showed the finished manuscript to Sidney Bernstein, the head of the British Information Service. Sidney reportedly came up with the idea to send it to Walt Disney.[N 2]

The manuscript arrived in Disney's hands in July 1942, and he considered using it as material for a live action/animated full-length feature film, offering Dahl a contract.[N 3] The film project was changed to an animated feature and entered pre-production, with characters "roughed out" and storyboards created.[10] Disney managed to have the story published in the December 1942 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine. At Dahl's urging, in early 1943, a revised version of the story, The Gremlins was published as a picture book by Random House (later updated and re-published in 2006 by Dark Horse Comics).[N 4]

The publication of The Gremlins by Random House consisted of a 50,000 run for the U.S. market [N 5]with Dahl ordering 50 copies for himself as promotional material for himself and the upcoming film, handing them out to everyone he knew, including Lord Halifax, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt who read it to her grandchildren.[9] The book was considered an international success with 30,000 more sold in Australia but initial efforts to reprint the book were precluded by a wartime paper shortage.[11] Reviewed in major publications, Dahl was considered a writer-of-note and his appearances in Hollywood to follow up with the film project were met with notices in Hedda Hopper's columns.[12][N 6]

The film project was reduced to an animated "short" and eventually cancelled in August 1943, when copyright and RAF rights could not be resolved. Thanks mainly to Disney, the story had its share of publicity which helped in introducing the concept to a wider audience. Issues #33-#41 of Walt Disney's Comics and Stories published between June 1943 and February 1944 contained a nine-episode series of short silent stories featuring a Gremlin Gus as their star. The first was drawn by Vivie Risto and the rest of them by Walt Kelly. This served as their introduction to the comic book audience.

While Roald Dahl was famous for making gremlins known world wide, many returning Air Servicemen swear they saw creatures tinkering with their equipment. One crewman swore he saw one before an engine malfunction that caused his B-25 Mitchell bomber to rapidly lose altitude, forcing the aircraft to return to base. Folklorist Hazen likewise offers his own alleged eyewitness testimony of these creatures, which appeared in an academically praised and peer-reviewed publication, describing an occasion he found "a parted cable which bore obvious tooth marks in spite of the fact that the break occurred in a most inaccessible part of the plane." At this point, Hazen states he heard "a gruff voice" demand, "How many times must you be told to obey orders and not tackle jobs you aren't qualified for? — This is how it should be done." Upon which Hazen heard a "musical twang" and another cable was parted.[13]

Critics of this idea state that the stress of combat and the dizzying heights caused such hallucinations, often believed to be a coping mechanism of the mind to help explain the many problems aircraft faced whilst in combat.

Aircraft gremlins in film and media

- On December 21, 1942, CBS aired "Gremlins," a whimsical story written by Louise Fletcher, on an episode of Orson Welles's patriotic radio series Ceiling Unlimited. U.S. Air Force officers discuss their experiences with the irritating creatures, and conclude that feeding them transforms them into an asset rather than a hindrance to aviation.[14][15]

- In 1943, Bob Clampett directed Falling Hare, a Merrie Melodies cartoon featuring Bugs Bunny. With Roald Dahl's book and Walt Disney's proposed film being the inspiration, this short has been one of the early Gremlin stories shown to cinema audiences in which multiple gremlins featured.[16] It features Bugs Bunny in conflict with a gremlin at an airfield. The Bugs Bunny cartoon was followed in 1944 by Russian Rhapsody, another Merrie Melodies short showing Russian gremlins sabotaging an aircraft piloted by Adolf Hitler. The gremlin in "Falling Hare" even has a color scheme that reflects one that was used on U.S. Army Air Forces training aircraft of the time, using dark blue (as on such an aircraft's fuselage) and a deep orange-yellow color (as used on the wings and tail surfaces).

- 1944 also saw animated gremlins playing a role in the romantic comedy starring Simone Simon called Johnny Doesn't Live Here Any More, with an uncredited Mel Blanc providing the voice.

- A 1963 episode of The Twilight Zone, "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" directed by Richard Donner and based on the short story of the same name by Richard Matheson, featured a gremlin attacking an airliner.[17] This episode was remade as a segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983).[18] In the original television episode, the gremlin appears as an almost ape-like creature which inspects the aircraft's wing with the curiosity of an animal and then proceeds to damage the wing. William Shatner plays a passenger, just recovered from a mental breakdown, who sees the Gremlin on the aircraft's wing. No one else sees the Gremlin and Shatner's character is removed from the aircraft on a stretcher with symptoms of psychosis. In the movie segment, the gremlin more resembles a troll or a goblin, with green skin and a frightening grin. This incarnation of the gremlin appears to be more intellectual and menacing, and is also shown to be capable of flying. The episode was famous enough to inspire numerous parodies:

- A gremlin makes an appearance in a Halloween special of The Simpsons paralleling The Twilight Zone's "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet", (the segment is even named "Terror at 5½ Feet") in which the gremlin attempts to destroy the wheel of Bart's school bus.

- A Tiny Toon special titled Night Ghoulery (a spoof of Night Gallery, with Babs presenting in Rod Serling's style) has a segment named "Gremlin on a Wing", which parodies "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" as well, with Plucky in William Shatner's place, accompanied by Hamton in an aircraft, and a gremlin similar to that which appeared in Bugs' short Falling Hare. In fact, this gremlin is so persistent, he even appears at the end as if he had impersonated the stewardess (who looks remarkably similar to Star Trek character Lt. Uhura).

- In Madagascar 2: Escape 2 Africa, Alex has a dream where he sees Mort (Alex calls him a gremlin) messing with the engine and falling off the aircraft.

- In Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls, Jim Carrey's character, Ace, starts a parody gag of The Twilight Zone's "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet", impersonating William Shatner and insisting that 'there is something on the wing.'

- The Real Ghostbusters episode Don't Forget The Motor City has the Ghostbusters traveling to Detroit to battle gremlins who are sabotaging a factory run by a fictional analog of General Motors.

- In Cast a Deadly Spell, an HBO TV-movie from 1991, gremlins are said to have been 'brought back from the pacific' to the US in the second world war, and are seen causing car and house damage.

- In the Extreme Ghostbusters episode Grease the Ghostbusters had to capture a gremlin that was damaging New York's machines, while at the same time the FBI believed them to be the cause of the sabotage, and after arresting them, they accidentally released him while on a plane. Surprisingly, the Twilight Zone episode with William Shatner is referenced.

- In the Johnny Bravo episode The Man Who Cried Clown, which is part of The Zone Where Normal Things Don't Happen Very Often, Johnny sees an evil clown on the wing of the aircraft and is having difficulty convincing anyone of its existence. When he gets rid of the evil Jacobs, he is informed that it and a good clown were needed to keep the aircraft in balance during flight.

- In the cartoon series Eek the Cat the episode 'The Eex Files' starts out with Eek on an aircraft beside a man claiming to see someone outside on the wing. Of course, when he looks there is no one there. At the end of the episode, Eek is dropped off by an alien on the wing of the aircraft and meets the gremlin, then promptly offers to help him "find his wallet". The final scene shows the half-crazed man looking out the window and "spazzing out" when he sees them both tearing up the wing.

- In the cartoon series American Dragon Jake Long one of the episodes features gremlins who mess with any type of mechanical devices and cause a lot of trouble during the episode until they are put to sleep and captured.

- In Disney's Epic Mickey Gremlins assist Mickey after he releases them.

Other gremlins

Gremlin Americanus: A Scrap Book Collection of Gremlins by artist and pilot Eric Sloane may predate the Roald Dahl publication. Published in 1942 by B.F. Jay & Co, the central characters are characterized as "pixies of the air" and are friends of both RAF and USAAC pilots. The gremlins are mischievous and give pilots a great deal of trouble, but they have never been known to cause fatal accidents but can be blamed for any untoward incident or "bonehead play", qualities that endear them to all flyers.[19][N 7]

See also Ssh! Gremlins by H.W. illustrated by Ronald Niebour ("Neb" of the Daily Maily), published by H. W. John Crowther Publication, England, in 1942. This booklet featured numerous humorous illustrations describing the gremlins as whimsical but essentially friendly folk. According to "H.W.", contrary to some reports, gremlins are a universal phenomenon and by no means only the friends of flying men.[20][N 8]

Not all depictions of gremlins show them on aircraft. Joe Dante's 1984 movie Gremlins and its sequel, Gremlins 2: The New Batch portray gremlins as malicious creatures whose only goal is to wreak havoc, whether in a small town or in a New York City skyscraper (although the character Mr. Futterman describes them as the same creatures that attacked aircraft in World War Two).

DC Comics' Stanley and His Monster depicts a gremlin named Schnitzel, who speaks with a thick German accent and is always trying to avoid an immigration officer, as he is an illegal alien.

American Motors produced a vehicle called the Gremlin between 1970 and 1978. A cartoon styled Gremlin icon was featured in advertisements as well as on the cars' gas caps.

Gremlin Trouble Comics were published between 1995 and 2005 by Anti-Ballistic Pixelations. In the 32 issue independent comic, Gremlins were machine spirits generally ambivalent to humans. They would, however work with and help a human they liked. The protagonist was a Storm Fairy who had lost her wings and was subsequently turned into a Gremlin Princess. Kilroy the famous piece of graffiti was identified in Australia as a gremlin.

See also

- Femlins, female gremlins featured in Playboy magazine

- Fifinella

- Froggy the Gremlin, a character on an American TV show in the 1950s

- Gremlin Graphics, the now defunct video games studio

- Gremlins

- Machine Elf

References

- ^ Hazen also claims that, "it was not until 1922 that anyone dared mention their name."

- ^ Dahl claimed that the gremlins were exclusively a Royal Air Force icon and he originated the term, but the elf-like figures had a very convoluted origin that predated his original writings.

- ^ Dahl was given permission by the British Air Ministry to work in Hollywood and an arrangement had been made that all proceeds from the eventual film would be split between the RAF Benevolent Fund and Dahl.[10]

- ^ The book had an autobiographical connection as Dahl had flown as a Hurricane fighter pilot in the RAF, and was temporarily on leave from operational flying after serious injuries sustained in a crash landing in Libya. He later returned to flying.

- ^ Both paperback and hardcover versions were printed in 1943.

- ^ In 1950, Collins Publishing (New York) published a limited reprint of The Gremlins.

- ^ On the front pastedown endpaper, Sloane's book featured a sketch of an aircraft in flight, with the pilot saying, "The Gremlins will get you if you don't watch out!!" and giving a thumbs up.[19]

- ^ The booklet was published posthumously as Wilson had died in 1940.

- Citations

- ^ a b c Hazen 1972, p. 465.

- ^ "Entry for 'Gremlin'." Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved: October 12, 2010.

- ^ Word Histories and Mysteries: From Abracadabra to Zeus. Lewisville, Texas: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2004. ISBN 978-0-618-45450-1.

- ^ Merry 2010, p. 66.

- ^ "The Gremlin Question." Royal Air Force Journal, Number 13, April 18, 1942.

- ^ Laming, John. "Do You Believe In Gremlins?" Stories of 10 Squadron RAAF in Townsville, 30 December 1998. Retrieved: October 12, 2010.

- ^ Desmond, John. "The Gremlins Reform: An R.A.F. Fable." The New York Times, April 11, 1943. Retrieved: October 12, 2010.

- ^ a b Sasser 1971, p. 1094.

- ^ a b Donald 2008, p. 147.

- ^ a b Conant 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Sturrock 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Conant 2008, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Hazen 1972, p. 466.

- ^ Smith 2010, p. 218.

- ^ Ceiling Unlimited — "Gremlins" at the Paley Center for Media; retrieved May 28, 2012

- ^ Merrie Melodies: Falling Hare at Internet Archive Movie Archive (The film is now in public domain)

- ^ "The Twilight Zone" TV series at IMDb

- ^ "The Twilight Zone" movie at IMDb

- ^ a b Sloane, Eric. Gremlin Americanus: A Scrap Book Collection of Gremlins. New York, B.F. Jay & Co., 1944, 1943, First edition 1942.

- ^ Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (H.W.). R. A. F. Book of the Season: Ssh! Gremlins by H.W. London: H. W. John Crowther Publication, 1942.

- Bibliography

- Conant, Jennet. The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7432-9458-4.

- Dahl, Flight Lieutenant Roald. The Gremlins: The Lost Walt Disney Production. Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Books, 2006 (reprint and updated copy of 1943 original publication). ISBN 978-1-59307-496-8.

- De La Rue, Keith. "Gremlins." delarue.net, updated August 23, 2004. Retrieved: October 11, 2010.

- Donald, Graeme. Sticklers, Sideburns & Bikinis: The Military Origins of Everyday Words and Phrases. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84603-300-1.

- Gower, Pauline. The ATA: Women with Wings. London: J. Long, limited, 1938.

- "Gremlins." Fantastic Fiction, a British online book site/biography source. Retrieved: October 11, 2010.

- Hazen, John W. "Gremlin." Funk and Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology and Legend. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1972. ISBN 978-0-308-40090-0.

- Merry, Lois K. Women Military Pilots of World War II: A History with Biographies of American, British, Russian and German Aviators. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2010. ISBN 978-0-7864-4441-0.

- Sasser, Sanford, Jr., ed. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aviation and Space, Volume 6. Los Angeles: A.F.E. Press, 1971, p. 1094. ISBN 978-0-308-40090-0.

- Smith, Ronald L. Horror Stars on Radio: The Broadcast Histories of 29 Chilling Hollywood Voices. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2010'. ISBN 978-0-7864-4525-7.

- Sturrock, Donald. Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of Roald Dahl. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4165-5082-2.

External links

- A longer article examining the Gremlin's origins

- The Inducks' list of Gremlin appearances in Disney comics

- More Info on the Dark Horse reprint of Disney and Dahl's Gremlins book

- The Crooked Gremlins (webcomic)