Holocene

| Subdivisions of the Quaternary Period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System/ Period |

Series/ Epoch |

Stage/ Age |

Age | |

| Quaternary | Holocene | Meghalayan | 0 | 4,200 |

| Northgrippian | 4,200 | 8,200 | ||

| Greenlandian | 8,200 | 11,700 | ||

| Pleistocene | 'Upper' | 11,700 | 129ka | |

| Chibanian | 129ka | 774ka | ||

| Calabrian | 774ka | 1.80Ma | ||

| Gelasian | 1.80Ma | 2.58Ma | ||

| Neogene | Pliocene | Piacenzian | 2.58Ma | 3.60Ma |

Subdivision of the Quaternary Period according to the ICS, as of January 2020.[1]

For the Holocene, dates are relative to the year 2000 (e.g. Greenlandian began 11,700 years before 2000). For the beginning of the Northgrippian a date of 8,236 years before 2000 has been set.[2] The Meghalayan has been set to begin 4,250 years before 2000.[1] 'Tarantian' is an informal, unofficial name proposed for a stage/age to replace the equally informal, unofficial 'Upper Pleistocene' subseries/subepoch. In Europe and North America, the Holocene is subdivided into Preboreal, Boreal, Atlantic, Subboreal, and Subatlantic stages of the Blytt–Sernander time scale. There are many regional subdivisions for the Upper or Late Pleistocene; usually these represent locally recognized cold (glacial) and warm (interglacial) periods. The last glacial period ends with the cold Younger Dryas substage. | ||||

| Preceded by the Pleistocene |

| Holocene Epoch |

|---|

|

|

Blytt–Sernander stages/ages

*Relative to year 2000 (b2k). †Relative to year 1950 (BP/Before "Present"). |

The Holocene ( /ˈhɒləˌsiːn, ˈhoʊ-/)[3][4] is the geological epoch that began after the Pleistocene[5] at approximately 11,700 years before present.[6] The Holocene is part of the Quaternary period. Its name comes from the Ancient Greek words ὅλος (holos, whole or entire) and καινός (kainos, new), meaning "entirely recent".[7] It has been identified with the current warm period, known as MIS 1, and is considered by some to be an interglacial period.

The Holocene encompasses the growth and impacts of the human species worldwide, including all its written history, development of major civilizations, and overall significant transition toward urban living in the present. Human impacts on modern-era Earth and its ecosystems may be considered of global significance for future evolution of living species, including approximately synchronous lithospheric evidence, or more recently atmospheric evidence of human impacts. The International Commission on Stratigraphy Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy’s working group on the 'Anthropocene' (coined by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in 2000) note this term is used to denote the present time interval in which many geologically significant conditions and processes have been profoundly altered by human activities. The 'Anthropocene' is not a formally defined geological unit.[8]

Overview

It is accepted by the International Commission on Stratigraphy that the Holocene started approximately 11,700 years ago.[6] The Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy quotes Gibbard and van Kolfschoten in Gradstein Ogg and Smith in stating the term 'Recent' as an alternative to Holocene is invalid and should not be used and also observe that the term Flandrian, derived from marine transgression sediments on the Flanders coast of Belgium has been used as a synonym for Holocene by authors who consider the last 10 000 years should have the same stage-status as previous interglacial events and thus be included in the Pleistocene.[9] The International Commission on Stratigraphy however considers the Holocene an epoch following the Pleistocene and specifically the last glacial period. Local names for the last glacial period include the Wisconsinan in North America,[10] the Weichselian in Europe,[11] the Devensian in Britain,[12] the Llanquihue in Chile[13] and the Otiran in New Zealand[14].

The Holocene can be subdivided into five time intervals, or chronozones, based on climatic fluctuations:[15]

- Preboreal (10 ka–9 ka),

- Boreal (9 ka–8 ka),

- Atlantic (8 ka–5 ka),

- Subboreal (5 ka–2.5 ka) and

- Subatlantic (2.5 ka–present).

The Blytt–Sernander classification of climatic periods defined, initially, by plant remains in peat mosses, is now being explored currently by geologists working in different regions studying sea levels, peat bogs and ice core samples by a variety of methods, with a view toward further verifying and refining the Blytt–Sernander sequence. They find a general correspondence across Eurasia and North America, though the method was once thought to be of no interest. The scheme was defined for Northern Europe, but the climate changes were claimed to occur more widely. The periods of the scheme include a few of the final pre-Holocene oscillations of the last glacial period and then classify climates of more recent prehistory.[citation needed]

Paleontologists have not defined any faunal stages for the Holocene. If subdivision is necessary, periods of human technological development, such as the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age, are usually used. However, the time periods referenced by these terms vary with the emergence of those technologies in different parts of the world.[citation needed]

Climatically, the Holocene may be divided evenly into the Hypsithermal and Neoglacial periods; the boundary coincides with the start of the Bronze Age in Europe. According to some scholars, a third division, the Anthropocene, has now begun.[16]

Geology

Continental motions due to plate tectonics are less than a kilometre over a span of only 10,000 years. However, ice melt caused world sea levels to rise about 35 m (115 ft) in the early part of the Holocene. In addition, many areas above about 40 degrees north latitude had been depressed by the weight of the Pleistocene glaciers and rose as much as 180 m (590 ft) due to post-glacial rebound over the late Pleistocene and Holocene, and are still rising today.[17]

The sea level rise and temporary land depression allowed temporary marine incursions into areas that are now far from the sea. Holocene marine fossils are known, for example, from Vermont and Michigan. Other than higher-latitude temporary marine incursions associated with glacial depression, Holocene fossils are found primarily in lakebed, floodplain, and cave deposits. Holocene marine deposits along low-latitude coastlines are rare because the rise in sea levels during the period exceeds any likely tectonic uplift of non-glacial origin.[citation needed]

Post-glacial rebound in the Scandinavia region resulted in the formation of the Baltic Sea. The region continues to rise, still causing weak earthquakes across Northern Europe. The equivalent event in North America was the rebound of Hudson Bay, as it shrank from its larger, immediate post-glacial Tyrrell Sea phase, to near its present boundaries.[citation needed]

Climate

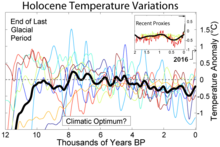

Climate has been fairly stable over the Holocene. Ice core records show that before the Holocene there was global warming after the end of the last ice age and cooling periods, but climate changes became more regional at the start of the Younger Dryas. During the transition from the last glacial to the Holocene, the Huelmo–Mascardi Cold Reversal in the Southern Hemisphere began before the Younger Dryas, and the maximum warmth flowed south to north from 11,000 to 7,000 years ago. It appears that this was influenced by the residual glacial ice remaining in the Northern Hemisphere until the later date.[citation needed]

The Holocene climatic optimum (HCO) was a period of warming in which the global climate became warmer. However, the warming was probably not uniform across the world. This period of warmth ended about 5,500 years ago with the descent into the Neoglacial. At that time, the climate was not unlike today's, but there was a slightly warmer period from the 10th–14th centuries known as the Medieval Warm Period. This was followed by the Little Ice Age, from the 13th or 14th century to the mid-19th century, which was a period of cooling.[citation needed]

Compared to glacial conditions, habitable zones have expanded northwards, reaching their northernmost point during the HCO. Greater moisture in the polar regions has caused the disappearance of steppe-tundra.[citation needed]

The temporal and spatial extent of Holocene climate change is an area of considerable uncertainty, with radiative forcing recently proposed to be the origin of cycles identified in the North Atlantic region. Climate cyclicity through the Holocene (Bond events) has been observed in or near marine settings and is strongly controlled by glacial input to the North Atlantic.[18][19] Periodicities of ≈2500, ≈1500, and ≈1000 years are generally observed in the North Atlantic.[20][21][22] At the same time spectral analyses of the continental record, which is remote from oceanic influence, reveal persistent periodicities of 1000 and 500 years that may correspond to solar activity variations during the Holocene epoch.[23] A 1500-year cycle corresponding to the North Atlantic oceanic circulation may have had widespread global distribution in the Late Holocene.[23]

Ecological developments

Animal and plant life have not evolved much during the relatively short Holocene, but there have been major shifts in the distributions of plants and animals. A number of large animals including mammoths and mastodons, saber-toothed cats like Smilodon and Homotherium, and giant sloths disappeared in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene—especially in North America, where animals that survived elsewhere (including horses and camels) became extinct. This extinction of American megafauna has been explained as caused by the arrival of the ancestors of Amerindians; though most scientists assert that climatic change also contributed. In addition, a controversial bolide impact over North America has been hypothesized to have triggered the Younger Dryas.[24]

Throughout the world, ecosystems in cooler climates that were previously regional have been isolated in higher altitude ecological "islands".[25]

The 8.2 ka event, an abrupt cold spell recorded as a negative excursion in the δ18O record lasting 400 years, is the most prominent climatic event occurring in the Holocene epoch, and may have marked a resurgence of ice cover. It has been suggested that this event was caused by the final drainage of Lake Agassiz, which had been confined by the glaciers, disrupting the thermohaline circulation of the Atlantic.[26] Subsequent research however, suggested that the discharge was probably superimposed upon a longer episode of cooler climate lasting up to 600 years and observed that the extent of the area affected was unclear.[27]

Human developments

The beginning of the Holocene corresponds with the beginning of the Mesolithic age in most of Europe; but in regions such as the Middle East and Anatolia with a very early neolithisation, Epipaleolithic is preferred in place of Mesolithic. Cultures in this period include Hamburgian, Federmesser, and the Natufian culture, during which the oldest inhabited places still existing on Earth were first settled, such as Jericho in the Middle East.[28] There is also evolving archeological evidence of proto-religion at locations such as Göbekli Tepe, as long ago as the 9th millennium BCE.[29]

Both are followed by the aceramic Neolithic (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and Pre-Pottery Neolithic B) and the pottery Neolithic. The Late Holocene brought advancements such as the bow and arrow and saw new methods of warfare in North America. Spear throwers and their large points were replaced by the bow and arrow with its small narrow points beginning in Oregon and Washington. Villages built on defensive bluffs indicate increased warfare, leading to food gathering in communal groups for protection rather than individual hunting.[30]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Cohen, K. M.; Finney, S. C.; Gibbard, P. L.; Fan, J.-X. (January 2020). "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ a b Mike Walker; et al. (December 2018). "Formal ratification of the subdivision of the Holocene Series/Epoch (Quaternary System/Period)" (PDF). Episodes. 41 (4). Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS): 213–223. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2018/018016. Retrieved 11 November 2019. This proposal on behalf of the SQS has been approved by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) and formally ratified by the Executive Committee of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS).

- ^ "Holocene". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ^ "Holocene". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ International Commission on Stratigraphy. "International Chronostratigraphic Chart". www.stratigraphy.org. Retrieved 2017-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b Walker, M.; Johnsen, S.; Rasmussen, S. O.; Popp, T.; Steffensen, J.-P.; Gibbard, P.; Hoek, W.; Lowe, J.; Andrews, J.; Bjo; Cwynar, L. C.; Hughen, K.; Kershaw, P.; Kromer, B.; Litt, T.; Lowe, D. J.; Nakagawa, T.; Newnham, R.; Schwander, J. (2009). "Formal definition and dating of the GSSP (Global Stratotype Section and Point) for the base of the Holocene using the Greenland NGRIP ice core, and selected auxiliary records" (PDF). J. Quaternary Sci. 24: 3–17. doi:10.1002/jqs.1227.

- ^ "Holocene". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Subcomission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, ICS » Working Groups". quaternary.stratigraphy.org. Retrieved 2017-06-18.

- ^ "Subcomission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, ICS » History of the stratigraphical nomenclature of the glacial period". quaternary.stratigraphy.org. Retrieved 2017-06-18.

- ^ Clayton, L.; Moran, S.R. (1982). "Chronology of late wisconsinan glaciation in middle North America". Quaternary Science Reviews. 1 (1): 55–82. doi:10.1016/0277-3791(82)90019-1.

- ^ Svendsen, J.I.; Astakhov, V.I.; Bolshiyanov, D.Y.; Demidov, I.; Dowdeswell, J.A.; Gataullin, V.; Hjort, C.; Hubberten, H.W.; Larsen, E.; Mangerud, J.; Melles, M.; Moller, P.; Saarnisto, M.; Siegert, M.J. (1999). "Maximum extent of the Eurasian ice sheets in the Barents and Kara Sea region during the Weichselian". Boreas. 28 (1): 234–242. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.1999.tb00217.x.

- ^ Eyles, N.E.; McCabe, A.M. (1989). "The Late Devensian (<22,000 BP) Irish Sea Basin: The sedimentary record of a collapsed ice sheet margin". Quaternary Science Reviews. 8 (4): 307–351. doi:10.1016/0277-3791(89)90034-6.

- ^ Denton, G.H.; Lowell, T.V.; Heusser, C.J.; Schluchter, C.; Andersern, B.G.; Heusser, L.E.; Moreno, P.I.; Marchant, D.R. (1999). "Geomorphology, stratigraphy, and radiocarbon chronology of LlanquihueDrift in the area of the Southern Lake District, Seno Reloncavi, and Isla Grande de Chiloe, Chile". Geografiska Annaler Series A Physical Geography. 81A (2): 167–229. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3676.1999.00057.x.

- ^ Newnham, R.; Vandergoes, M.; Hendy, C.; Lowe, D.J.; Preusser, F. (2007). "A terrestrial palynological record for the last two glacial cycles from southwestern New Zealand". Quaternary Science Reviews. 26: 517–535. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.05.005. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ Mangerud, J, Anderson, ST, Berglund, BE, Donner, JJ (October 1, 1974). "Quaternary stratigraphy of Norden: a proposal for terminology and classification" (PDF). Boreas. 3: 109–128. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.1974.tb00669.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fred Pearce (2007). With Speed and Violence, p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8070-8576-9

- ^ "England is sinking while Scotland rises above sea levels, according to new study". Telegraph. 2009-10-07. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- ^ Bond, G.; et al. (1997). "A Pervasive Millennial-Scale Cycle in North Atlantic Holocene and Glacial Climates" (PDF). Science. 278 (5341): 1257–1266. Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1257B. doi:10.1126/science.278.5341.1257. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bond, G.; et al. (2001). "Persistent Solar Influence on North Atlantic Climate During the Holocene". Science. 294 (5549): 2130–2136. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2130B. doi:10.1126/science.1065680. PMID 11739949.

- ^ Bianchi, G.G.; McCave, I.N. (1999). "Holocene periodicity in North Atlantic climate and deep-ocean flow south of Iceland". Nature. 397: 515–517.

- ^ Viau, A.E.; Gajewski, K.; Sawada, M.C.; Fines, P. (2006). "Millennial-scale temperature variations in North America during the Holocene". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111: D09102. Bibcode:2006JGRD..111.9102V. doi:10.1029/2005JD006031.

- ^ Debret, M.; Sebag, D.; Crosta, X.; Massei, N.; Petit, J.-R.; Chapron, E.; Bout-Roumazeilles, V. (2009). "Evidence from wavelet analysis for a mid-Holocene transition in global climate forcing". Quaternary Science Reviews. 28: 2675–2688. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.06.005.

- ^ a b Kravchinsky, V.A.; Langereis, C.G.; Walker, S.D.; Dlusskiy, K.G.; White, D. "Discovery of Holocene millennial climate cycles in the Asian continental interior: Has the sun been governing the continental climate?". Global and Planetary Change. 110: 386–396. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.02.011.

- ^ Dalton, Rex (May 2007). "Blast from the Past? A controversial new idea suggests that a big space rock exploded on or above North America at the end of the last ice age" (PDF). Nature. 447 (7142): 256–257. doi:10.1038/447256a. PMID 17507957.

- ^ Singh, Ashbindu; Programme, United Nations Environment (2005). One Planet, Many People: Atlas of Our Changing Environment. UNEP/Earthprint. ISBN 9789280725711.

- ^ Barber, D.C (1999). "Forcing of the cold event of 8,200 years ago by catastrophic drainage of Laurentide lakes" (PDF). Nature. 400 (6742): 344–348. doi:10.1038/22504.

- ^ Rohling, E.J (2005). "Centennial-scale climate cooling with a sudden event around 8,200 years ago" (PDF). Nature. 434 (7036): 975–979. doi:10.1038/nature03421.

- ^ "Jericho", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Curry, Andrew (November 2008). "Göbekli Tepe: The World's First Temple?". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2009-03-17. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Snow, Dean (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall.

Further reading

- Roberts, Neil (2014). The Holocene: an environmental history (3rd ed.). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5521-2.

- Mackay, A. W.; Battarbee, R. W.; Birks, H. J. B.; et al., eds. (2003). Global change in the Holocene. London: Arnold. ISBN 0-340-76223-3.

- Hunt CO and Rabett RJ. (2013). Holocene landscape intervention and plant food production strategies in island and mainland Southeast Asia. Journal of Archaeological Science