Intersex human rights

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, or genitals, that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies."[1]

Intersex people face stigmatisation and discrimination from birth, particularly when an intersex variation is visible. In some countries (particularly in Africa and Asia) this may include infanticide, abandonment and the stigmatization of families. Mothers in East Africa may be accused of witchcraft, and the birth of an intersex child may be described as a curse.[2][3][4]

Intersex infants and children, such as those with ambiguous outer genitalia, may be surgically and/or hormonally altered to fit perceived more socially-acceptable sex characteristics. However, this is considered controversial, with no firm evidence of good outcomes.[5] Such treatments may involve sterilization. Adults, including elite female athletes, have also been subjects of such treatment.[6][7] Increasingly these issues are recognized as human rights abuses, with statements from UN agencies,[8][9] the Australian parliament,[10] and German and Swiss ethics institutions.[11] Intersex organizations have also issued joint statements over several years, including the Malta declaration by the third International Intersex Forum.

Implementation of human rights protections in legislation and regulation has progressed more slowly. In 2011, Christiane Völling won the first successful case brought against a surgeon for non-consensual surgical intervention.[12] In 2015, the Council of Europe recognized for the first time a right for intersex persons to not undergo sex assignment treatment.[13] In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw nonconsensual medical interventions to modify sex anatomy, including that of intersex people.[14][15]

Other human rights and legal issues include the right to life, protection from discrimination, access to justice and reparations, access to information, and legal recognition.[13][16] Few countries so far protect intersex people from discrimination, or provide access to reparations for harmful practices.[13][16]

Intersex and human rights

Research indicates a growing consensus that diverse intersex bodies are normal—if relatively rare—forms of human biology,[17] and human rights institutions are placing increasing scrutiny on medical practices and issues of discrimination against intersex people. A 2013 first international pilot study. Human Rights between the Sexes, by Dan Christian Ghattas,[18][19] found that intersex people are discriminated against worldwide:

Intersex individuals are considered individuals with a «disorder» in all areas in which Western medicine prevails. They are more or less obviously treated as sick or «abnormal», depending on the respective society.

The Council of Europe highlights several areas of concern:

- unnecessary "normalising" treatment of intersex persons, and unnecessary pathologisation of variations in sex characteristics.

- unnecessary medicalisation is said to also impact a right to life.

- inclusion in equal treatment and hate crime law; facilitating access to justice and reparations.

- access to information, medical records, peer and other counselling and support.

- respecting self-determination in gender recognition, through expeditious access to official documents.[13]

However, the implementation, codification and enforcement of intersex human rights remains slow. These actions take place through legislation, regulation and court cases, detailed below.

"Pinkwashing"

Multiple organizations have highlighted appeals to LGBT rights recognition that fail to address the issue of unnecessary "normalising" treatments on intersex children, using the portmanteau term "pinkwashing". In June 2016, Organisation Intersex International Australia pointed to contradictory statements by Australian governments, suggesting that the dignity and rights of LGBTI (LGBT and intersex) people are recognized while, at the same time, harmful practices on intersex children continue.[20]

In August 2016, Zwischengeschlecht described actions to promote equality or civil status legislation without action on banning "intersex genital mutilations" as a form of pinkwashing.[21] The organization has previously highlighted evasive government statements to UN Treaty Bodies that conflate intersex, transgender and LGBT issues, instead of addressing harmful practices on infants.[22]

Physical integrity and bodily autonomy

Intersex people face stigmatisation and discrimination from birth. In some countries, particularly in Africa and Asia, this may include infanticide, abandonment and the stigmatization of families. Mothers in east Africa may be accused of witchcraft, and the birth of an intersex child may be described as a curse.[2][3] Abandonments and infanticides have been reported in Uganda,[2] Kenya,[23] south Asia,[24] and China.[4] In 2015, it was reported that an intersex Kenyan adolescent, Muhadh Ishmael, was mutilated and later died. He had previously been described as a curse on his family.[23]

Non-consensual medical interventions to modify the sex characteristics of intersex people take place in all countries where the human rights of intersex people have been explored.[18] Such interventions have been criticized by the World Health Organization, other UN bodies such as the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and an increasing number of regional and national institutions. In low and middle income countries, the cost of healthcare may limit access to necessary medical treatment at the same time that other individuals experience coercive medical interventions.[4]

Several rights have been stated as affected by stigmatization and coercive medical interventions on minors:

- the right to life.[13]

- the right to privacy, including a right to personal autonomy or self-determination regarding medical treatment.[10][11]

- prohibitions against torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.[8][10]

- a right to physical integrity[25] and/or bodily autonomy.[15][26]

- additionally, the best interests of the child may not be served by surgeries aimed at familial and social integration.[11]

These issues have been addressed by a rapidly increasing number of international institutions including, in 2015, the Council of Europe, the United Nations Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the World Health Organization. In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw coercive medical interventions.[14][15] In the same year, the Council of Europe became the first institution to state that intersex people have the right not to undergo sex affirmation interventions.[13]

Constitutional Court of Colombia

Although not many cases of children with intersex conditions are available, a case taken to the Constitutional Court of Colombia led to changes in their treatment.[27] The case restricted the power of doctors and parents to decide surgical procedures on children's ambiguous genitalia after the age of five, while continuing to permit interventions on younger children. Due to the decision of the Constitutional Court of Colombia on Case 1 Part 1 (SU-337 of 1999), doctors are obliged to inform parents on all the aspects of the intersex child. Parents can only consent to surgery if they have received accurate information, and cannot give consent after the child reaches the age of five. By then the child will have, supposedly, realized their gender identity.[28] The court case led to the setting of legal guidelines for doctors' surgical practice on intersex children.

Maltese legislation

In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw non-consensual medical interventions in a Gender Identity Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act.[14][15] The Act recognizes a right to bodily integrity and physical autonomy, explicitly prohibiting modifications to children's sex characteristics for social factors:

14. (1) It shall be unlawful for medical practitioners or other professionals to conduct any sex assignment treatment and/or surgical intervention on the sex characteristics of a minor which treatment and/or intervention can be deferred until the person to be treated can provide informed consent: Provided that such sex assignment treatment and/or surgical intervention on the sex characteristics of the minor shall be conducted if the minor gives informed consent through the person exercising parental authority or the tutor of the minor. (2) In exceptional circumstances treatment may be effected once agreement is reached between the Interdisciplinary Team and the persons exercising parental authority or tutor of the minor who is still unable to provide consent: Provided that medical intervention which is driven by social factors without the consent of the minor, will be in violation of this Act.[29]

The Act was widely welcomed by civil society organizations.[26][30][31]

Chilean regulations

In January 2016, the Ministry of Health of Chile ordered the suspension of unnecessary normalization treatments for intersex children, including irreversible surgery, until they reach an age when they can make decisions on their own.[32][33] The regulations were superseded in August 2016.[34]

Right to life

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD or PIGD) refers to genetic testing of embryos prior to implantation (as a form of embryo profiling), and sometimes even of oocytes prior to fertilization. PGD is considered in a similar fashion to prenatal diagnosis. When used to screen for a specific genetic condition, the method makes it highly likely that the baby will be free of the condition under consideration. PGD thus is an adjunct to assisted reproductive technology, and requires in vitro fertilization (IVF) to obtain oocytes or embryos for evaluation. The technology allows discrimination against those with intersex traits.

Georgiann Davis argues that such discrimination fails to recognize that many people with intersex traits led full and happy lives.[35] Morgan Carpenter highlights the appearance of several intersex variations in a list by the UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority of "serious" "genetic conditions" that may be de-selected, including 5 alpha reductase deficiency and androgen insensitivity syndrome, traits evident in elite women athletes and "the world's first openly intersex mayor".[36] Organisation Intersex International Australia has called for the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council to prohibit such interventions, noting a "close entanglement of intersex status, gender identity and sexual orientation in social understandings of sex and gender norms, and in medical and medical sociology literature".[37]

In 2015, the Council of Europe published an Issue Paper on Human rights and intersex people, remarking:

Intersex people’s right to life can be violated in discriminatory “sex selection” and “preimplantation genetic diagnosis, other forms of testing, and selection for particular characteristics”. Such de-selection or selective abortions are incompatible with ethics and human rights standards due to the discrimination perpetrated against intersex people on the basis of their sex characteristics.[13]

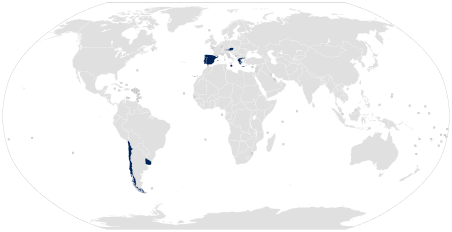

Protection from discrimination

A handful of jurisdictions so far provide explicit protection from discrimination for intersex people. South Africa was the first country to explicitly add intersex to legislation, as part of the attribute of 'sex'.[38] Australia was the first country to add an independent attribute, of 'intersex status'.[39] Malta was the first to adopt a broader framework of 'sex characteristics', through legislation that also ended modifications to the sex characteristics of minors undertaken for social and cultural reasons.[26] Bosnia-Herzegovina listed as "sex characteristics"[40][41] Greece prohibits discrimination and hate crimes based on "sex characteristics", since 24 December 2015.[42][43]

Education

An Australian survey of 272 persons born with atypical sex characteristics, published in 2016, found that 18% of respondents (compared to an Australian average of 2%) failed to complete secondary school, with early school leaving coincident with pubertal medical interventions, bullying and other factors.[44]

Employment

A 2015 Australian survey of people born with atypical sex characteristics found high levels of poverty, in addition to very high levels of early school leaving, and higher than average rates of disability.[45] An Employers guide to intersex inclusion published by Pride in Diversity and Organisation Intersex International Australia also discloses cases of discrimination in employment.[46]

Healthcare

Discrimination protection intersects with involuntary and coercive medical treatment. Maltese protections on grounds of sex characteristics provides explicit protection against unnecessary and harmful modifications to the sex characteristics of children.[15][26]

In May 2016, the United States Department of Health and Human Services issued a statement explaining Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act stating that the Act prohibits "discrimination on the basis of intersex traits or atypical sex characteristics" in publicly-funded healthcare, as part of a prohibition of discrimination "on the basis of sex".[47]

Sport

In 2013, it was disclosed in a medical journal that four unnamed elite female athletes from developing countries were subjected to gonadectomies (sterilization) and partial clitoridectomies (female genital mutilation) after testosterone testing revealed that they had an intersex condition.[48][49] Testosterone testing was introduced in the wake of the Caster Semenya case, of a South African runner subjected to testing due to her appearance and vigor.[48][49][50][51] There is no evidence that innate hyperandrogenism in elite women athletes confers an advantage in sport.[52][53] While Australia protects intersex persons from discrimination, the Act contains an exemption in sport.

Access to justice and reparations

Access to reparation appears limited, with a scarcity of legal cases.

Christiane Völling case, Germany

In Germany in 2011, Christiane Völling won what may be the first successful case against her medical treatment. The surgeon was ordered to pay €100,000 in damages[54][55] after a legal battle that began in 2007, thirty years after the removal of her reproductive organs.[12][56]

Benjamín-Maricarmen case, Chile

On August 12, 2005, the mother of a child, Benjamín, filed a lawsuit against the Maule Health Service after the child's male gonads and reproductive system were removed without informing the parents of the nature of the surgery. The child had been raised as a girl. The claim for damages was initiated in the Fourth Court of Letters of Talca, but ended up in the Supreme Court of Chile. On November 14, 2012, the Court sentenced the Maule Health Service for "lack of service" and to pay compensation of 100 million pesos for moral and psychological damages caused to Benjamín, and another 5 million for each of the parents.[57][58]

M.C. v. Aaronson case, USA

In the United States the M.C. v. Aaronson case, advanced by Advocates for Informed Choice with the Southern Poverty Law Centre was brought before the courts in 2013.[59][60][61] In 2015, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit dismissed the case, stating that, "it did not “mean to diminish the severe harm that M.C. claims to have suffered” but that a reasonable official in 2006 did not have fair warning from then-existing precedent that performing sex assignment surgery on sixteen-month-old M.C. violated a clearly established constitutional right."[62][63] State suits were subsequently filed.[62]

Michaela Raab case, Germany

In 2015, Michaela Raab sued doctors in Nuremberg, Germany who failed to properly advise her. Doctors stated that they "were only acting according to the norms of the time - which sought to protect patients against the psychosocial effects of learning the full truth about their chromosomes."[55] On 17 December 2015, the Nuremberg State Court ruled that the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg Clinic must pay damages and compensation.[64]

Access to information

With the rise of modern medical science in Western societies, many intersex people with ambiguous external genitalia have had their genitalia surgically modified to resemble either female or male genitals. Surgeons pinpointed the birth of intersex babies as a "social emergency".[65] A secrecy-based model was also adopted, in the belief that this was necessary to ensure “normal” physical and psychosocial development.[11][66][67] Disclosure also included telling people that they would never meet anyone else with the same condition.[10] Access to medical records has also historically been challenging.[13] Yet the ability to provide free, informed consent depends on the availability of information.

The Council of Europe[13] and World Health Organization[68] acknowledge the necessity for improvements in information provision, including access to medical records.

Some intersex organizations claim that secrecy-based models have been perpetuated by a shift in clinical language to Disorders of sex development. Morgan Carpenter of Organisation Intersex International Australia quotes the work of Miranda Fricker on "hermeneutical injustice" where, despite new legal protections from discrimination on grounds of intersex status, "someone with lived experience is unable to even make sense of their own social experiences" due to the deployment of clinical language and "no words to name the experience".[69]

Legal recognition

According to the Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions, few countries have provided for the legal recognition of intersex people. The Forum states that the legal recognition of intersex people is:

- firstly about access to the same rights as other men and women, when assigned male or female;

- secondly it is about access to administrative corrections to legal documents when an original sex assignment is not appropriate; and

- thirdly, while opt in schemes may help some individuals, legal recognition is not about the creation of a third sex or gender classification for intersex people as a population, but instead is about enabling an opt-in scheme for any individual who seeks it.[16]

In some jurisdictions, access to any form of identification document can be an issue.[70]

Gender identities

Like all individuals, some intersex individuals may be raised as a particular sex (male or female) but then identify with another later in life, while most do not.[71][72][73] Like non-intersex people, some intersex individuals may not identify themselves as either exclusively female or exclusively male. A 2012 clinical review suggests that between 8.5-20% of persons with intersex conditions may experience gender dysphoria,[74] while sociological research in Australia, a country with a third 'X' sex classification, shows that 19% of people born with atypical sex characteristics selected an "X" or "other" option, while 52% are women, 23% men and 6% unsure.[45][75]

Access to identification documents

Depending on the jurisdiction, access to any birth certificate may be an issue,[70] including a birth certificate with a sex marker.[76]

In 2014, in the case of Baby ‘A’ (Suing through her Mother E.A) & another v Attorney General & 6 others [2014], a Kenyan court ordered the Kenyan government to issue a birth certificate to a five-year-old child born in 2009 with ambiguous genitalia.[77] In Kenya a birth certificate is necessary for attending school, getting a national identity document, and voting.[77] Many intersex persons in Uganda are understood to be stateless due to historical difficulties in obtaining identification documents, despite a birth registration law that permits intersex minors to change assignment.[78]

Access to the same rights as other men and women

The Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions states that:

Recognition before the law means having legal personhood and the legal protections that flow from that. For intersex people, this is neither primarily nor solely about amending birth registrations or other official documents. Firstly, it is about intersex people who have been issued a male or a female birth certificate being able to enjoy the same legal rights as other men and women[16]

Binary categories

Access to a birth certificate with a correct sex marker may be an issue for people who do not identify with their sex assigned at birth,[13] or it may only be available accompanied by surgical requirements.[16]

Third categories

The passports and identification documents of Australia and some other nationalities have adopted "X" as a valid third category besides "M" (male) and "F" (female), at least since 2003.[79][80] In 2013, Germany became the first European nation to allow babies with characteristics of both sexes to be registered as indeterminate gender on birth certificates, amidst opposition and skepticism from intersex organisations who point out that the law appears to mandate exclusion from male or female categories.[81][82][83] The Council of Europe acknowledged this approach, and concerns about recognition of third and blank classifications in a 2015 Issue Paper, stating that these may lead to "forced outings" and "lead to an increase in pressure on parents of intersex children to decide in favour of one sex."[13] The Issue Paper argues that "further reflection on non-binary legal identification is necessary":

Mauro Cabral, Global Action for Trans Equality (GATE) Co-Director, indicated that any recognition outside the “F”/”M” dichotomy needs to be adequately planned and executed with a human rights point of view, noting that: “People tend to identify a third sex with freedom from the gender binary, but that is not necessarily the case. If only trans and/or intersex people can access that third category, or if they are compulsively assigned a third sex, then the gender binary gets stronger, not weaker”[13]

Intersex rights by jurisdiction

Africa

| Country/Jurisdiction | Physical integrity and bodily autonomy | Reparations | Anti-discrimination protection | Access to identification documents | Access to same rights as other men and women | Changing M/F identification documents | Third gender or sex classifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Americas

| Country/Jurisdiction | Physical integrity and bodily autonomy | Reparations | Anti-discrimination protection | Access to identification documents | Access to same rights as other men and women | Changing M/F identification documents | Third gender or sex classifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 2012, case before the Supreme Court of Chile.[92][58] | |||||||

| Partial, in healthcare[99] |

Asia

| Country/Jurisdiction | Physical integrity and bodily autonomy | Reparations | Anti-discrimination protection | Access to identification documents | Access to same rights as other men and women | Changing M/F identification documents | Third gender or sex classifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Europe

| Country/Jurisdiction | Physical integrity and bodily autonomy | Reparations | Anti-discrimination protection | Access to identification documents | Access to same rights as other men and women | Changing M/F identification documents | Third gender or sex classifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oceania

| Country/Jurisdiction | Physical integrity and bodily autonomy | Reparations | Anti-discrimination protection | Access to identification documents | Access to same rights as other men and women | Changing M/F identification documents | Third gender or sex classifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

See also

- Intersex human rights reports

- Intersex medical interventions

- Discrimination against intersex people

- Legal recognition of intersex people

Notes

- ^ "Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex" (PDF). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Civil Society Coalition on Human Rights and Constitutional Law; Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum; Rainbow Health Foundation; Sexual Minorities Uganda; Support Initiative for Persons with Congenital Disorders (2014). "Uganda Report of Violations based on Sex Determination, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation".

- ^ a b Grady, Helen; Soy, Anne (May 4, 2017). "The midwife who saved intersex babies". BBC World Service, Kenya.

- ^ a b c Beyond the Boundary - Knowing and Concerns Intersex (October 2015). "Intersex report from Hong Kong China, and for the UN Committee Against Torture: the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment".

- ^ "Submission 88 to the Australian Senate inquiry on the involuntary or coerced sterilisation of people with disabilities in Australia". Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group (APEG). 27 June 2013.

- ^ Rebecca Jordan-Young, Peter Sonksen, Katrina Karkazis (2014). "Sex, health, and athletes". BMJ. 348: g2926. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2926. PMID 24776640.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Macur, Juliet (6 October 2014). "Fighting for the Body She Was Born With". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture" (PDF). Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. February 2013.

- ^ "Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization, An interagency statement". World Health Organization. May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Australian Senate Community Affairs Committee (October 2013). "Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia".

- ^ a b c d e Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics NEK-CNE (November 2012). On the management of differences of sex development. Ethical issues relating to "intersexuality".Opinion No. 20/2012 (PDF). 2012. Berne.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "German Gender-Assignment Case Has Intersexuals Hopeful". DW.COM. Deutsche Welle. 12 December 2007. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Council of Europe; Commissioner for Human Rights (April 2015), Human rights and intersex people, Issue Paper

- ^ a b c Reuters (1 April 2015). "Surgery and Sterilization Scrapped in Malta's Benchmark LGBTI Law". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d e Star Observer (2 April 2015). "Malta passes law outlawing forced surgical intervention on intersex minors". Star Observer.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions (June 2016). Promoting and Protecting Human Rights in relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Sex Characteristics. Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions. ISBN 978-0-9942513-7-4.

- ^ Zderic, Stephen (2002). Pediatric gender assignment : a critical reappraisal ; [proceedings from a conference ... in Dallas in the spring of 1999 which was entitled "pediatric gender assignment - a critical reappraisal"]. New York, NY [u.a.]: Kluwer Acad. / Plenum Publ. ISBN 0306467593.

- ^ a b Ghattas, Dan Christian; Heinrich Böll Foundation (September 2013). "Human Rights Between the Sexes" (PDF).

- ^ "A preliminary study on the life situations of inter* individuals". OII Europe. 4 November 2013.

- ^ "Submission: list of issues for Australia's Convention Against Torture review". Organisation Intersex International Australia. June 28, 2016.

- ^ ""Intersex legislation" that allows the daily mutilations to continue = PINKWASHING of IGM practices". Zwischengeschlecht. August 28, 2016.

- ^ "TRANSCRIPTION > UK Questioned over Intersex Genital Mutilations by UN Committee on the Rights of the Child - Gov Non-Answer + Denial". Zwischengeschlecht. May 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Odero, Joseph (December 23, 2015). "Intersex in Kenya: Held captive, beaten, hacked. Dead". 76 CRIMES. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- ^ Warne, Garry L.; Raza, Jamal (September 2008). "Disorders of sex development (DSDs), their presentation and management in different cultures". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 9 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1007/s11154-008-9084-2. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 18633712.

- ^ United Nations; Committee on the Rights of Persons with Diabilities (April 17, 2015). Concluding observations on the initial report of Germany (advance unedited version). Geneva: United Nations.

- ^ a b c d Cabral, Mauro (April 8, 2015). "Making depathologization a matter of law. A comment from GATE on the Maltese Act on Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics". Global Action for Trans Equality. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ^ Curtis, Skyler (2010–2011). "Reproductive Organs and Differences of Sex Development: The Constitutional Issues Created by the Surgical Treatment of Intersex Children". McGeorge Law Review. 42: 863. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Corte Constitucional de Colombia: Sentencia T-1025/02". Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Malta (April 2015), Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act: Final version

- ^ OII Europe (April 1, 2015). "OII-Europe applauds Malta's Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act. This is a landmark case for intersex rights within European law reform". Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan (April 2, 2015). "We celebrate Maltese protections for intersex people". Organisation Intersex International Australia. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ^ "Chilean Government Stops the 'Normalization' of Intersex Children". OutRight Action International. January 14, 2016.

- ^ "Chilean Ministry of Health issues instructions stopping "normalising" interventions on intersex children". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 11 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Complementa circular 18 que instruye sobre ciertos aspectos de la atencion de salud a niños y niñas intersex" (PDF). Ministerio de Salud. 23 August 2016.

- ^ Davis, Georgiann (October 2013). "The Social Costs of Preempting Intersex Traits". The American Journal of Bioethics. 13 (10): 51–53. doi:10.1080/15265161.2013.828119. ISSN 1526-5161. PMID 24024811. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan (July 18, 2014). "Morgan Carpenter at LGBTI Human Rights in the Commonwealth conference". Glasgow.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Carpenter, Morgan; Organisation Intersex International Australia (April 30, 2014). Submission on the Review of Part B of the Ethical Guidelines for the Use of Assisted Reproductive Technology in Clinical Practice and Research, 2007 (Report). Sydney: Organisation Intersex International Australia.

- ^ a b "Judicial Matters Amendment Act, No. 22 of 2005, Republic of South Africa, Vol. 487, Cape Town" (PDF). 11 January 2006.

- ^ "Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013, No. 98, 2013, C2013A00098". ComLaw. 2013.

- ^ "Anti-discrimination Law Updated in Bosnia-Herzegovina". ILGA-Europe.

- ^ "LGBTI people are now better protected in Bosnia and Herzegovina".

- ^ a b Template:El icon "ΝΟΜΟΣ ΥΠ' ΑΡΙΘ. 3456 Σύμφωνο συμβίωσης, άσκηση δικαιωμάτων, ποινικές και άλλες διατάξεις".

- ^ Template:El icon"Πρώτη φορά, ίσοι απέναντι στον νόμο".

- ^ Jones, Tiffany (March 11, 2016). "The needs of students with intersex variations". Sex Education: 1–17. doi:10.1080/14681811.2016.1149808. ISSN 1468-1811. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ a b Jones, Tiffany; Hart, Bonnie; Carpenter, Morgan; Ansara, Gavi; Leonard, William; Lucke, Jayne (February 2016). Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-208-0. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan; Hough, Dawn (2014). Employers' Guide to Intersex Inclusion. Sydney, Australia: Pride in Diversity and Organisation Intersex International Australia. ISBN 978-0-646-92905-7.

- ^ interACT. "Federal Government Bans Discrimination Against Intersex People in Health Care". interactadvocates. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ^ a b Fénichel, Patrick; Paris, Françoise; Philibert, Pascal; Hiéronimus, Sylvie; Gaspari, Laura; Kurzenne, Jean-Yves; Chevallier, Patrick; Bermon, Stéphane; Chevalier, Nicolas; Sultan, Charles (June 2013). "Molecular Diagnosis of 5α-Reductase Deficiency in 4 Elite Young Female Athletes Through Hormonal Screening for Hyperandrogenism". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 98 (6): –1055-E1059. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3893. ISSN 0021-972X. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ a b Jordan-Young, R. M.; Sonksen, P. H.; Karkazis, K. (April 2014). "Sex, health, and athletes". BMJ. 348 (apr28 9): –2926-g2926. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2926. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 24776640. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- ^ "Semenya told to take gender test". BBC Sport. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ "A Lab is Set to Test the Gender of Some Female Athletes". New York Times. 30 July 2008.

- ^ Bermon, Stéphane; Garnier, Pierre Yves; Lindén Hirschberg, Angelica; Robinson, Neil; Giraud, Sylvain; Nicoli, Raul; Baume, Norbert; Saugy, Martial; Fénichel, Patrick; Bruce, Stephen J.; Henry, Hugues; Dollé, Gabriel; Ritzen, Martin (August 2014). "Serum Androgen Levels in Elite Female Athletes". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 99: –2014-1391. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1391. ISSN 0021-972X. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Branch, John (27 July 2016). "Dutee Chand, Female Sprinter With High Testosterone Level, Wins Right to Compete". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht (August 12, 2009). "Christiane Völling: Hermaphrodite wins damage claim over removal of reproductive organs". Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ^ a b The Local (February 27, 2015). "Intersex person sues clinic for unnecessary op". Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ DW Staff (August 2010). "Christiane Völling". German Ethics Council. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ "Condenan al H. de Talca por error al determinar sexo de bebé". diario.latercera.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 February 2017.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ a b García, Gabriela. "Identidad forzada". www.paula.cl (in Spanish).

- ^ Southern Poverty Law Centre (May 14, 2013). "Groundbreaking SLPC Lawsuit Accuses South Carolina Doctors and Hospitals of Unnecessary Surgery on Infant". Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ^ Reis, Elizabeth (May 17, 2013). "Do No Harm: Intersex Surgeries and the Limits of Certainty". Nursing Clio. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ^ Dreger, Alice (May 16, 2013). "When to Do Surgery on a Child With 'Both' Genitalia". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ^ a b Largent, Emily (March 5, 2015). "M.C. v. Aaronson". Petrie-Flom Center, Harvard Law.

- ^ interACT (January 27, 2015). "Update on M.C.'s Case – The Road to Justice can be Long, but there is more than one path for M.C." Retrieved 2017-02-18.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht (December 17, 2015). "Nuremberg Hermaphrodite Lawsuit: Michaela "Micha" Raab Wins Damages and Compensation for Intersex Genital Mutilations!". Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ Coran, Arnold G.; Polley, Theodore Z. (July 1991). "Surgical management of ambiguous genitalia in the infant and child". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 26 (7): 812–820. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(91)90146-K. PMID 1895191.

- ^ Holmes, Morgan. "Is Growing up in Silence Better Than Growing up Different?". Intersex Society of North America.

- ^ Intersex Society of North America. "What's wrong with the way intersex has traditionally been treated?".

- ^ World Health Organization (2015). Sexual health, human rights and the law. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241564984.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan (February 3, 2015). Intersex and ageing. Organisation Intersex International Australia.

- ^ a b c "Kenya takes step toward recognizing intersex people in landmark ruling". Reuters.

- ^ Money, John; Ehrhardt, Anke A. (1972). Man & Woman Boy & Girl. Differentiation and dimorphism of gender identity from conception to maturity. USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-1405-7.

- ^ Domurat Dreger, Alice (2001). Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex. USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00189-3.

- ^ Marañón, Gregorio (1929). Los estados intersexuales en la especie humana. Madrid: Morata.

- ^ Furtado P. S.; et al. (2012). "Gender dysphoria associated with disorders of sex development". Nat. Rev. Urol. 9: 620–627. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2012.182. PMID 23045263.

- ^ Organisation Intersex International Australia (July 28, 2016), Demographics, retrieved 2016-09-30

- ^ Viloria, Hida (November 6, 2013). "Op-ed: Germany's Third-Gender Law Fails on Equality". The Advocate.

- ^ a b Migiro, Katy. "Kenya takes step toward recognizing intersex people in landmark ruling". Reuters.

- ^ Support Initiative for Persons with Congenital Disorders (2016), Baseline Survey on Intersex Realities in East Africa - Specific Focus on Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda

- ^ Holme, Ingrid (2008). "Hearing People's Own Stories". Science as Culture. 17 (3): 341–344. doi:10.1080/09505430802280784. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "New Zealand Passports - Information about Changing Sex / Gender Identity". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Third sex option on birth certificates". Deutsche Welle. 1 November 2013.

- ^ "Sham package for Intersex: Leaving sex entry open is not an option". OII Europe. 15 February 2013.

- ^ "'X' gender: Germans no longer have to classify their kids as male or female". RT. 3 November 2013.

- ^ Chigiti, John (September 14, 2016). "The plight of the intersex child". The Star, Kenya. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ^ Collison, Carl (October 27, 2016). "SA joins the global fight to stop unnecessary genital surgery on intersex babies". Mail&Guardian.

- ^ United Nations; Committee on the Rights of the Child (October 27, 2016). "Concluding observations on the second periodic report of South Africa".

- ^ Kaggwa, Julius (2016-09-16). "I'm an intersex Ugandan – life has never felt more dangerous". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ Kaggwa, Julius (October 9, 2016). "Understanding intersex stigma in Uganda". Intersex Day. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ^ Parliament of Uganda (2015), Registration of Persons Act

- ^ a b Justicia Intersex; Zwischengeschlecht.org (2017). "NGO Report to the 6th and 7th Periodic Report of Argentina on the Convention against Torture (CAT)" (PDF). Buenos Aires.

- ^ Global Action for Trans Equality (14 May 2012). "Gender identity Law in Argentina: an opportunity for all". Sexuality Policy Watch.

- ^ "Condenan al H. de Talca por error al determinar sexo de bebé". diario.latercera.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 February 2017.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ Chile, Cámara de Diputados de. "Proyectos de Ley Sistema de garantías de los derechos de la niñez". www.camara.cl (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ "Comisión de la Cámara aprueba que niñas y niños trans tengan derecho a desarrollar su identidad de género". www.movilh.cl (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Inter, Laura (2015). "Finding My Compass". Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics. Volume 5, Number 2: 95–98.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Inter, Laura (October 2016). "The situation of the intersex community in Mexico". Intersex Day. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ^ Baruch, Ricardo (October 13, 2016), Sí, hay personas intersexuales en México, Animal Politico

- ^ a b interACT (June 2016). Recommendations from interACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth regarding the List of Issues for the United States for the 59th Session of the Committee Against Torture (PDF).

- ^ interACT (2016). "Federal Government Bans Discrimination Against Intersex People in Health Care". Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ^ "California Senate Bill "SB-179 Gender identity: female, male, or nonbinary" to enact the Gender Recognition Act, to authorize the change of gender on the new birth certificate to be female, male, or nonbinary". California Legislative Information. January 24, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ O'Hara, Mary Emily (September 26, 2016). "Californian Becomes Second US Citizen Granted 'Non-Binary' Gender Status". NBC News. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ O'Hara, Mary Emily (December 29, 2016). "Nation's First Known Intersex Birth Certificate Issued in NYC". Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ^ a b UK Home Office (December 2016). "Bangladesh: Sexual orientation and gender identity" (PDF). UK Home Office Country Policy and Information Note. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Beyond the Boundary - Knowing and Concerns Intersex (October 2015). "Intersex report from Hong Kong China, and for the UN Committee Against Torture: the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment".

- ^ United Nations; Committee against Torture (2015). "Concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of China". Geneva: United Nations.

- ^ United Nations; Committee against Torture (2015). "Concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of China with respect to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region". Geneva: United Nations.

- ^ Equal Opportunities Commission (March 9, 2017). "EOC & GRC of CUHK Issue Statement Calling for the Introduction of Legislation against Discrimination on the Grounds of Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status".

- ^ Karthikeyan, Ragamalika (February 3, 2017). "Activists say surgical 'correction' of intersex babies at birth wrong, govt doesn't listen". The News Minute.

- ^ a b Supreme Court of India 2014. "Supreme Court recognises the right to determine and express one's gender; grants legal status to 'third gender'" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Sunil Babu Pant and Others/ v. Nepal Government and Others, Supreme Court of Nepal" (PDF). National Judicial Academy Law Journal. April 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Regmi, Esan (2016). Stories of Intersex People from Nepal. Kathmandu.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Anti-discrimination Law Updated in Bosnia-Herzegovina". ILGA-Europe.

- ^ Amnesty International (2017). First, Do No Harm.

- ^ Amnesty International (2017). "First, Do No Harm: ensuring the rights of children born intersex". Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ^ a b c McDonald, Henry; Others (July 16, 2015). "Ireland passes law allowing trans people to choose their legal gender". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ Ghattas, Dan Christian; ILGA-Europe (2016). "Standing up for the human rights of intersex people – how can you help?" (PDF).

- ^ Guillot, Vincent; Zwischengeschlecht (April 3, 2016). "NGO Report to the 7th Periodic Report of France on the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)". Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b Sénat; Blondin, Maryvonne; Bouchoux, Corinne (2017-02-23). Variations du développement sexuel : lever un tabou, lutter contre la stigmatisation et les exclusions. 2016-2017 (in French). Paris, France: Sénat.

- ^ Klöppel, Ulrike (December 2016). "Zur Aktualität kosmetischer Operationen „uneindeutiger" Genitalien im Kindesalter". Gender Bulletin (42). ISSN 0947-6822.

- ^ OII Germany (January 20, 2017). "OII Germany: CEDAW Shadow Report. With reference to the combined Seventh and Eighth Periodic Report from the Federal Republic of Germany on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)" (PDF).

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht.org (March 2015). Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations Of Children With Variations Of Sex Anatomy: NGO Report on the Answers to the List of Issues (LoI) in Relation to the Initial Periodic Report of Germany on the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (PDF). Zurich.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ International Commission of Jurists. "In re Völling, Regional Court Cologne, Germany (6 February 2008)". Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht (12 August 2009). "Christiane Völling: Hermaphrodite wins damage claim over removal of reproductive organs". Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht (17 December 2015). "Nuremberg Hermaphrodite Lawsuit: Michaela "Micha" Raab Wins Damages and Compensation for Intersex Genital Mutilations!". Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ "Third sex option on birth certificates". Deutsche Welle. 1 November 2013.

- ^ "Intersex: Third Gender in Germany" (Spiegel, Huff Post, Guardian, ...): Silly Season Fantasies vs. Reality of Genital Mutilations". Zwischengeschlecht. 1 November 2013.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht.org (December 2015). "Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations Of Children With Variations Of Sex Anatomy: NGO Report to the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Periodic Report of Ireland on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)" (PDF). Zurich.

- ^ United Nations; Committee on the Rights of Child (February 4, 2016). "Concluding observations on the combined third to fourth periodic reports of Ireland (advance unedited version)". Geneva: United Nations.

- ^ "DISCRIMINATION (SEX AND RELATED CHARACTERISTICS) (JERSEY) REGULATIONS 2015". 2015.

- ^ Dalli, Miriam (3 February 2015). "Male, Female or X: the new gender options on identification documents". Malta Today.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht.org (March 2014). "Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations Of Children With Variations Of Sex Anatomy: NGO Report to the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Periodic Report of Switzerland on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)" (PDF). Zurich.

- ^ United Nations; Committee on the Rights of Child (February 26, 2015). "Concluding observations on the combined second to fourth periodic reports of Switzerland". Geneva.

- ^ United Nations; Committee on the Rights of Child (September 7, 2015). "Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of Switzerland". Geneva.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ United Nations; Committee on the Rights of Child (June 2016). "Concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland". Geneva: United Nations.

- ^ Zwischengeschlecht.org; IntersexUK; OII-UK; The UK Intersex Association (April 2016). Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations of Children with Variations of Sex Anatomy: NGO Report to the 5th Periodic Report of the United Kingdom on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (PDF). Zurich.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Payton, Naith (July 23, 2015). "Comment: Why the UK's gender recognition laws desperately need updating". The Pink Paper.

- ^ a b Androgen Insensitivity Support Syndrome Support Group Australia; Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand; Organisation Intersex International Australia; Black, Eve; Bond, Kylie; Briffa, Tony; Carpenter, Morgan; Cody, Candice; David, Alex; Driver, Betsy; Hannaford, Carolyn; Harlow, Eileen; Hart, Bonnie; Hart, Phoebe; Leckey, Delia; Lum, Steph; Mitchell, Mani Bruce; Nyhuis, Elise; O'Callaghan, Bronwyn; Perrin, Sandra; Smith, Cody; Williams, Trace; Yang, Imogen; Yovanovic, Georgie (March 2017), Darlington Statement, archived from the original on 2017-03-21, retrieved March 21, 2017

- ^ a b "We welcome the Senate Inquiry report on the Exposure Draft of the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill 2012". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 21 February 2013.

- ^ a b "On intersex birth registrations". OII Australia. 13 November 2009.

- ^ "Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender, 30 May 2013". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Human Rights Commission (2016), Intersex Roundtable Report 2016 The practice of genital normalisation on intersex children in Aotearoa New Zealand (PDF)

- ^ Department of Internal Affairs. "General information regarding Declarations of Family Court as to sex to be shown on birth certificates" (PDF).