Zirid dynasty: Difference between revisions

Alter: title. Add: doi, issue, volume, year, journal. Upgrade ISBN10 to 13. | Use this tool. Report bugs. | #UCB_Gadget |

R Prazeres (talk | contribs) Adding three new maps in infobox for three periods (with switcher template), each based on a map from published sources; see talk page (and file descriptions) for more details. |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| year_end = 1148 |

| year_end = 1148 |

||

| image_flag = |

| image_flag = |

||

| image_map = |

| image_map = {{Switcher |

||

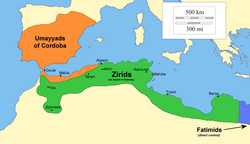

| [[File:Zirid control circa 980 (version 2).png|250px]] |

|||

| image_map_caption = Zirid territory (green) at its maximum extent around the year 980 <ref>[http://www.rosenweinshorthistory.com/wp-content/uploads/map-44.pdf Fragmentation of the Islamic World, c.1000]</ref><ref>[https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-europe-latter-part-of-10th-century-bartholomew-1876-antique-map-102714560.html Europe (Latter part of 10th Century)<nowiki>]</nowiki>'. BARTHOLOMEW, 1876]</ref> |

|||

| Maximum extent of Zirid control c. 980 |

|||

| [[File:Zirid control circa 1000.png|250px]] |

|||

| Approximate Zirid territory c. 1000 |

|||

| [[File:Zirid control in late 11th century.png|250px]] |

|||

| Zirid territory in mid-to-late 11th century |

|||

}} |

|||

| image_map_caption = |

|||

| p1 = Fatimid Caliphate |

| p1 = Fatimid Caliphate |

||

| s1 = Hammadid dynasty |

| s1 = Hammadid dynasty |

||

Revision as of 09:23, 25 July 2022

Zirid dynasty الدولة الزيرية | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 972–1148 | |||||||||||||

| Status | Vassal state of the Fatimid Caliphate (972–1048) Independent (1048–1148) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | 'Ashir (972–1014) Kairouan (1014–1057) Mahdia (1057–1148)[1][2][3][4] | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Berber (primary), Maghrebi Arabic, African Latin, Hebrew | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (Shia Islam, Sunni, Ibadi), Christianity (Roman Catholicism), Judaism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy (Emirate) | ||||||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||||||

• 973–984 | Buluggin ibn Ziri | ||||||||||||

• 1121–1148 | Al-Hassan ibn Ali | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 972 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1148 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

| History of Tunisia |

|---|

|

|

|

The Zirid dynasty (Arabic: الزيريون, romanized: az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri (Arabic: بنو زيري, romanized: banū zīrī), or the Zirid state (Arabic: الدولة الزيرية, romanized: ad-dawla az-zīriyya)[5] was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from modern-day Algeria which ruled the central Maghreb from 972 to 1014 and Ifriqiya (eastern Maghreb) from 972 to 1148.[2][6]

Descendants of Ziri ibn Menad, a military leader of the Fatimid Caliphate and the eponymous founder of the dynasty, the Zirids were emirs who ruled in the name of the Fatimids. The Zirids gradually established their autonomy in Ifriqiya through military conquest until officially breaking with the Fatimids in the mid-11th century. The rule of the Zirid emirs opened the way to a period in North African history where political power was held by Berber dynasties such as the Almoravid dynasty, Almohad Caliphate, Zayyanid dynasty, Marinid Sultanate and Hafsid dynasty.[7]

Under Buluggin ibn Ziri the Zirids extended their control westwards and briefly occupied Fez and much of present-day Morocco after 980, but encountered resistance from the local Zenata Berbers who gave their allegiance to the Caliphate of Cordoba.[4][8][9][10] To the east, Zirid control was extended over Tripolitania after 978[11] and as far as Ajdabiya (in present-day Libya),[12] while the Kalbid Emirate of Sicily recognized Zirid suzerainty in 1036.[13] One branch of the Zirids, the Hammadids, broke away from the main branch after various internal disputes and took control of the territories of the central Maghreb after 1015.[14] The Zirids proper were then designated as Badicides and occupied only Ifriqiya between 1048 and 1148.[15] Part of the dynasty fled to al-Andalus and later founded, in 1019, the Taifa of Granada on the ruins of the Caliphate of Cordoba.[6] The Zirids of Granada were again defeated by the expansion of the Almoravids, who annexed their kingdom in 1090,[16] while the Badicides and the Hammadids remained independent. Following the recognition of the Sunni Muslim Abbasid Caliphate and the assertion of Ifriqiya and the Central Maghreb as independent kingdoms of Sunni obedience in 1048, the Fatimids reportedly masterminded the migration of the Hilalians to the Maghreb. In the 12th century, the Hilalian invasions combined with the attacks of the Normans of Sicily on the littoral weakened Zirid power. The Almohad Caliphate finally conquered the central Maghreb and Ifriqiya in 1152, thus unifying the whole of the Maghreb and ending the Zirid dynasties.[8]

History

The Zirids were Sanhaja Berbers, from the sedentary Talkata tribe,[17][18] originating from the area of modern Algeria. They later advertised their ancestry to Himyarite kings as a title to nobility and this was taken up by court historians of this period.[19][20] In the 10th century this tribe served as vassals of the Fatimid Caliphate, an Isma'ili Shi'a state that challenged the authority of the Sunni Abbasid caliphs. The progenitor of the Zirid dynasty, Ziri ibn Manad (r. 935–971) was installed as governor of the central Maghreb (roughly north-eastern Algeria today) on behalf of the Fatimids, guarding the western frontier of the Fatimid Caliphate.[21][22] With Fatimid support Ziri founded his own capital and palace at 'Ashir, south-east of Algiers, in 936.[23][24][25] He proved his worth as a key ally in 945, during the Kharijite rebellion of Abu Yazid, when he helped break Abu Yazid's siege of the Fatimid capital, Mahdia.[14][26] After playing this valuable role, he expanded 'Ashir with a new palace circa 947.[23][27] In 959 he aided Jawhar al-Siqili on a Fatimid military expedition which successfully conquered Fez and Sijilmasa in present-day Morocco. On their return home to the Fatimid capital they paraded the emir of Fez and the “Caliph” Ibn Wasul of Sijilmasa in cages in a humiliating manner.[28][29][30] After this success, Ziri was also given Tahart to govern on behalf of the Fatimids.[31] He was eventually killed in battle against the Zanata in 971.[24][32]

When the Fatimids moved their capital to Egypt in 972, Ziri's son Buluggin ibn Ziri (r. 971–984) was appointed viceroy of Ifriqiya. He soon led a new expedition west and by 980 he had conquered Fez and most of Morocco, which had previously been retaken by the Umayyads of Cordoba in 973.[33][34] He also led a successful expedition to Barghawata territory, from which he brought back a large number of slaves to Ifriqiya.[35] In 978 the Fatimids also granted Buluggin overlordship of Tripolitania (in present-day Libya), allowing him to appoint his own governor in Tripoli. In 984 Buluggin died in Sijilmasa from an illness and his successor decided to abandon Morocco in 985.[36][37][38] The removal of the fleet to Egypt made the retention of Kalbid Sicily impossible, while Algeria broke away under the governorship of Hammad ibn Buluggin, Buluggin's son.[38]

After 1001 Tripolitania also broke away under the leadership of Fulful ibn Sa'id ibn Khazrun, a Maghrawa leader who founded the Banu Khazrun dynasty, which endured until 1147.[39][11][12] Fulful fought a protracted war against Badis ibn al-Mansur and sought outside help from the Fatimids and even from the Umayyads of Cordoba, but after his death in 1009 the Zirids were able to retake Tripoli for a time. The region nonetheless remained effectively under control of the Banu Khazrun, who fluctuated between practical autonomy and full independence, often playing the Fatimids and the Zirids against each other.[40][41][11][42]

The Zirid period of Tunisia is considered a high point in its history, with agriculture, industry, trade and learning, both religious and secular, all flourishing, especially in their capital, Kairouan.[43] The early reign of al-Mu'izz ibn Badis was particularly prosperous and marked the height of their power in Ifriqiya.[26] Management of the area by later Zirid rulers was neglectful as the agricultural economy declined, prompting an increase in banditry among the rural population.[43] The relationship between the Zirids their Fatimid overlords varied - in 1016 thousands of Shiites lost their lives in rebellions in Ifriqiya, and the Fatimids encouraged the defection of Tripolitania from the Zirids, but nevertheless the relationship remained close. In 1049 the Zirids broke away completely by adopting Sunni Islam and recognizing the Abbasids of Baghdad as rightful Caliphs, a move which was popular with the urban Arabs of Kairouan.[3][44]

When the Zirids renounced the Fatimids and recognized the Abbasid Caliphs in 1048-49, the Fatimids sent the Arab tribes of the Banu Hilal and the Banu Sulaym to Ifriqiya. The Zirids attempted to stop their advance towards Ifriqiya, they sent 30,000 Sanhaja cavalry to meet the 3,000 Arab cavalry of Banu Hilal in the Battle of Haydaran of 14 April 1052.[45] Nevertheless, the Zirids were decisively defeated and were forced to retreat, opening the road to Kairouan for the Hilalian Arab cavalry.[45][46][47] The resulting anarchy devastated the previously flourishing agriculture, and the coastal towns assumed a new importance as conduits for maritime trade and bases for piracy against Christian shipping, as well as being the last holdout of the Zirids.[46]

The Banu Hilal invasions eventually forced al-Mu'izz ibn Badis to abandon Kairouan in 1057 and move his capital to Mahdia, while the Banu Hilal largely roamed and pillaged the interior of the former Zirid territories.[48][26] In 1074 the al-Mui'zz's son and successor, Tamim, sent a naval expedition to Calabria where they ravaged the Italian coasts, plundered Nicotera and enslaved many of its inhabitants. The next year (1075) another Zirid raid resulted in the capture of Mazara in Sicily; however, the Zirid emir rethought his involvement in Sicily and decided to withdraw, abandoning what they had briefly held.[49] In 1087, the Zirid capital, Mahdia, was sacked by the Pisans.[50] According to Ettinghausen, Grabar, and Jenkins-Madina, the Pisa Griffin is believed to have been part of the spoils taken during the sack.[51] Between 1146 and 1148 the Normans of Sicily conquered all the coastal towns, and in 1152 the last Zirids in Algeria were superseded by the Almohad Caliphate.

Economy

The Zirid period was a time of great economic prosperity. The departure of the Fatimids to Cairo, far from ending this prosperity, saw its amplification under the Zirid and Hammadid rulers. Referring to the government of the Zirid Emir al-Mu'izz ibn Badis, the historian Ibn Khaldun reports: "It [has] never [been] seen by the Berbers of that country a kingdom more vast and more flourishing than his own." The northern regions produced wheat in large quantities, while the region of Sfax was a major hub of olive production and the cultivation of the date was an important part of the local economy in Biskra. Other crops such as sugar cane, saffron, cotton, sorghum, millet and chickpea were grown. The breeding of horses and sheep flourished and fishing provided plentiful food. The Mediterranean was also an important part of the economy, even though it was, for a time, abandoned after the departure of the Fatimids, when the priority of the Zirid Emirs turned to territorial and internal conflicts. Their maritime policy enabled them to establish trade links, in particular for the importation of the timber necessary for their fleet, and enabled them to begin an alliance and very close ties with the Kalbid Emirs of Sicily. They did, however, face blockade attempts by the Venetians and Normans, who sought to reduce their wood supply and thus their dominance in the region.[52]

The Arab chronicler Ibn Hawqal visited and described the city of Algiers in the Zirid era: "The city of Algiers is built on a gulf and surrounded by a wall. It contains a large number of bazaars and a few sources of good water near the sea. It is from these sources that the inhabitants draw the water they drink. In the outbuildings of this town are very extensive countryside and mountains inhabited by several tribes of the Berbers. The chief wealth of the inhabitants consists of herds of cattle and sheep grazing in the mountains. Algiers supplies so much honey that it forms an export object, and the quantity of butter, figs and other commodities is so great that it is exported to Kairouan and elsewhere".[52]

Culture

Literature

Abd al-Aziz ibn Shaddad was a Zirid chronicler and prince.[54] He wrote Kitab al-Jam' wa 'l-bayan fi akhbar al-Qayrawan (كتاب الجمع والبيان في أخبار القيروان) about the history of Qayrawan.[54]

Architecture

The Zirid dynasty was responsible for various constructions and renovations throughout the Maghreb. Zirid and Hammadid architecture in North Africa was closely linked to Fatimid architecture,[55]: 83 but also influenced Norman architecture in Sicily.[56][55]: 100 The Zirid palace at 'Ashir, built in 934 by Ziri ibn Manad (who served the Fatimids), is one of the oldest palaces in the Maghreb to have been discovered and excavated.[57] As independent rulers, however, the Zirids of Ifriqiya built relatively few grand structures. They reportedly built a new palace at al-Mansuriyya, a former Fatimid capital near Kairouan, but it has not been found by modern archeologists.[57]: 123 Buluggin ibn Ziri commissioned the production of a minbar for the Mosque of the Andalusians in Fez. The minbar, whose original fragments are now preserved in a museum, bears an inscription that dates it to the year 980, around the time of Buluggin's military expedition to this region.[58]: 249 In Kairouan the Great Mosque was restored by Al-Mu'izz ibn Badis. The wooden maqsura within the mosque today is believed to date from this time.[55]: 87 It is the oldest maqsura in the Islamic world to be preserved in situ and was commissioned by al-Mu῾izz ibn Badis in the first half of the 11th century (though later restored). It is notable for its woodwork, which includes an elaborately carved Kufic inscription dedicated to al-Mu'izz.[59][60] Under Al-Mu’izz the Zirids had also built the Sidi Abu Marwan mosque in Annaba.[61]

The Hammadids, for their part, built an entirely new fortified capital at Qala'at Bani Hammad, founded in 1007. Although abandoned and destroyed in the 12th century, the city has been studied by modern archeologists and is one of the best-preserved medieval Islamic capitals in the world.[57]: 125

Zirid rulers

The regnal dates of rulers are indicated first according to the Islamic calendar and then with the corresponding Gregorian dates in parentheses.

- Ziri ibn Manad d. 360 AH (971 CE)[62]

- Abul-Futuh Sayf ad-Dawla Buluggin ibn Ziri 361-373 AH (972-984 CE)

- Abul-Fat'h al-Mansur ibn Buluggin 373-386 AH (984-996 CE)

- Abu Qatada Nasir ad-Dawla Badis ibn Mansur 386-406 AH (996-1016 CE)

- Sharaf ad-Dawla al-Muizz ibn Badis 406-454 AH (1016–1062 CE) declared independence from the Fatimids and changed the khutba to refer to the Abbasid Caliph in 1048, changed capital to Mahdia in 1057 after Kairouan was lost to the Banu Hilal

- Abu Tahir Tamim ibn al-Mu'izz 454-501 AH (1062–1108 CE)

- Yahya ibn Tamim 501-509 AH (1108–1116 CE)

- Ali ibn Yahya 509-515 AH (1116–1121 CE)

- Abu'l-Hasan al-Hasan ibn Ali 515-543 AH (1121–1148 CE)

Offshoots of the Zirid dynasty

Zirids of Granada

The Zirids were also the ruling dynasty of the Taifa of Granada, a Berber kingdom in Al-Andalus. The founder was the brother of Buluggin, Zawi ben Ziri, a general of the Caliphate of Córdoba under Caliph Hisham II.

After the death of Almanzor in Medinaceli on 12 August 1002 (25 Ramadan 392), a civil war broke out in Al-Andalus, and General Zawi ibn Ziri destroyed several cities, such as Medina Azahara in 1011 and Córdoba in 1013. He founded the Taifa of Granada and the city of Granada itself,[63][64][65][66] and then declared himself its first emir. He died of poison in Algiers in 1019.

In 1013 the Zirids founded the Albaicín District in Granada which is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. During the rule of Zawi, an Umayyad pretender al-Murtada attempted to conquer Granada, however he was defeated.[67]

During the reign of Badis Ibn Habus he defeated the Abbadids of Seville one of the strongest taifas and also defeated the taifa of Almeria and took control of its territory.[68][69] He also defeated the Hammudids and conquered the Taifa of Malaga.[70]

The arts and civil construction under the rule of the Zirid governors and emirs in Al-Andalus, mainly in the Taifa of Granada, were very important. An example is the Cadima Alcazaba in Albayzin, Granada, and part of the old wall surrounding Granada.

Hammadid dynasty

General timeline

Photo gallery

-

The ruins of Achir, a fortress founded by Ziri ibn Menad, the eponym of the Zirid dynasty -

The Maqsurah of Al-Muizz in the Mosque of Uqba, Kairouan, produced during the reign of Al-Muizz ibn Badis -

The Casbah of Algiers, founded by Bologhine ibn Ziri and classed by the Unesco

See also

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Ar-Raqiq, a courtier, poet and historian, secretary to al-Muizz ibn Badis.

Further reading

- King, Matt (2022). Dynasties Intertwined: The Zirids of Ifriqiya and the Normans of Sicily. Cornell University Press.

References

Citations

- ^ Phillip C. Naylor (15 January 2015). North Africa, Revised Edition: A History from Antiquity to the Present. University of Texas Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-292-76190-2.

- ^ a b "Zirid Dynasty | Muslim dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ a b Idris H. Roger, L'invasion hilālienne et ses conséquences, in : Cahiers de civilisation médiévale (43), Jul.-Sep. 1968, pp.353-369. [1]

- ^ a b Julien, Charles-André (1 January 1994). Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord: des origines à 1830 (in French). Payot. p. 295. ISBN 9782228887892.

- ^ محمد،, صلابي، علي محمد (1998). الدولة العبيدية في ليبيا (in Arabic). دار البيارق،.

- ^ a b "Qantara - Les Zirides et les Hammadides (972-1152)". www.qantara-med.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Hrbek, Ivan; Africa, Unesco International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of (1 January 1992). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. J. Currey. p. 172. ISBN 9780852550939.

- ^ a b Meynier, Gilbert (1 January 2010). L'Algérie, coeur du Maghreb classique: de l'ouverture islamo-arabe au repli (698-1518) (in French). La Découverte. p. 158. ISBN 9782707152312.

- ^ Simon, Jacques (1 January 2011). L'Algérie au passé lointain: de Carthage à la régence d'Alger (in French). Harmattan. p. 165. ISBN 9782296139640.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (5 March 2014). Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-134-25986-1.

- ^ a b c Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 67.

- ^ a b Fehérvári, Géza (2002). Excavations at Surt (Medinat Al-Sultan) Between 1977 and 1981. Department of Antiquities. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-900971-00-3.

- ^ Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- ^ a b Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2004). "The Zirids and Hammadids". The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780748696482.

- ^ Idris, Hady Roger (1968). "L'invasion hilālienne et ses conséquences". Cahiers de civilisation médiévale. 11 (43): 353–369. doi:10.3406/ccmed.1968.1452.

- ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1 January 2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9780748621378.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 64.

- ^ Ilahiane, Hsain (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Scarecrow Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8108-6490-0.

- ^ Baadj, Amar S. (11 August 2015). Saladin, the Almohads and the Banū Ghāniya: The Contest for North Africa (12th and 13th centuries). BRILL. p. 12. ISBN 978-90-04-29857-6.

- ^ Brett, Michael (3 May 2019). The Fatimids and Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-76474-5.

- ^ Brett 2017, p. 54, 63.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 19.

- ^ a b Brett, Michael (2008). "Ashīr". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 9789004161658.

- ^ a b Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 66.

- ^ Brett 2017, p. 54.

- ^ a b c Tibi 2002.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 188.

- ^ Halm, Heinz (1996). The Empire of the Mahdi: The Rise of the Fatimids. Brill. p. 399. ISBN 90-04-10056-3.

- ^ Messier, Ronald A.; Miller, James A. (2015). The Last Civilized Place: Sijilmasa and Its Saharan Destiny. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292766655

- ^ Pellat, Charles (1991). "Midrār". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3

- ^ Brett 2017, p. 75.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (2014). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-317-87041-8.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip C. (2015). North Africa, Revised Edition: A History from Antiquity to the Present. University of Texas Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-292-76190-2.

- ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, p. 67, 75.

- ^ Hady Roger, Idris (1962). La berbérie oriental sous les Zirides (PDF). Adrien-Maisonneuve. pp. 57 58.

- ^ Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong; Henry Louis Gates (2 February 2012). Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- ^ Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Placesedited by Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger

- ^ a b Tibi 2002, p. 514.

- ^ Oman, G.; Christides, V.; Bosworth, C.E. (1960–2007). "Ṭarābulus al-G̲h̲arb". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ Lewicki, T. (1960–2007). "Mag̲h̲rāwa". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ Garnier, Sébastien (2020). "Libya until 1500". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 9789004161658.

- ^ Brett 2017, p. 128, 142.

- ^ a b Brill, E.J. (1987). "Fatamids". Libya: Encyclopedia of Islam. Library of Congress. ISBN 9004082654. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ Berry, LaVerle. "Fatamids". Libya: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ a b Idris, H. R. (24 April 2012), "Ḥaydarān", Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Brill, retrieved 26 September 2021

- ^ a b Idris, Hady Roger (1968). "L'invasion hilālienne et ses conséquences". Cahiers de civilisation médiévale. 11 (43): 353–369. doi:10.3406/ccmed.1968.1452. ISSN 0007-9731.

- ^ Schuster, Gerald (2009). "Reviewed work: Die Beduinen in der Vorgeschichte Tunesiens. Die « Invasion » der Banū Hilāl, Gerald Schuster". Arabica. 56 (4/5). Brill: 487–492. doi:10.1163/057053909X12475581297885. JSTOR 25651679.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Abun-Nasr 1987, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Brown, Gordon S. (2015). The Norman Conquest of Southern Italy and Sicily. McFarland. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7864-5127-2.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 302.

- ^ a b Sénac, Philippe; Cressier, Patrice (10 October 2012). Histoire du Maghreb médiéval: VIIe-XIe siècle (in French). Armand Colin. p. 150. ISBN 9782200283421.

- ^ "Islamic art from museums around the world". Arab News. 18 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b Talbi, M. (24 April 2012). "Ibn S̲h̲addād". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition.

- ^ a b c Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ L. Hadda, Zirid and Hammadid palaces in North Africa and its influence on Norman architecture in Sicily, in Word, Heritage and Knowledge, a cura di C. Gambardella, XVI Forum International di Studi-Le vie dei Mercanti, Napoli-Capri 14-16 giugno 2018, Roma 2018, pp. 323-332

- ^ a b c Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190624552.

- ^ Dodds, Jerrilynn D., ed. (1992). Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870996371.

- ^ "Qantara - Maqsûra d'al-Mu'izz". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Maqsura". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Hippone. Xavier Delestre. Édisud.

- ^ Idris, H.R. (1962). Le berbérie orientale sous les Zīrīdes: Xe-XIIe siècles. Paris: Librarie d'Amérique et d'Orient. pp. 831–833.

- ^ Breve historia de al-Ándalus Ana Martos Rubio Ediciones Nowtilus S.L.,

- ^ Crónica de la España musulmana p.35 Leopoldo Torres Balbás Instituto de España

- ^ El Albaicín: paraíso cerrado, conflicto urbano p.178 Antonio Malpica Cuello Diputación Provincial de Granada

- ^ Infidel Kings and Unholy Warriors: Faith, Power, and Violence in the Age of Crusade and Jihad Brian A. Catlos Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

- ^ España musulmana: hasta la caída del Califato de Córdoba, 711-1031 de J.C., Volume 4

- ^ The Zīrids of Granada - Andrew Handler University of Miami Press, 1974

- ^ Ibn ?azm of Cordoba: The Life and Works of a Controversial Thinker

- ^ Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain

- ^ a b "Zirid Dynasty - Muslim dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

Sources

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674.

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. Edinburgh: Edinbugh University Press. ISBN 9781474421522.

- Tibi, Amin (2002). "Zirids". The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. XI. Brill.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn, eds. (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture, 650-1250. Yale University Press.

- Zirid Dynasty Encyclopædia Britannica

- Historical map showing location of Zirid Kingdom c. 1000