User:Epipelagic/sandbox/box3: Difference between revisions

Epipelagic (talk | contribs) tsk |

Epipelagic (talk | contribs) tsk |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

* [http://www.mollusca.co.nz/speciesdetail.php?speciesid=1192&species=Alcithoe%20arabica New Zealand mollusca] |

* [http://www.mollusca.co.nz/speciesdetail.php?speciesid=1192&species=Alcithoe%20arabica New Zealand mollusca] |

||

* [http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PA0810/S00220.htm QMS open to widespread abuse Mfish officials say] |

|||

* [http://www.greens.org.nz/policy/sea Green Ocean policy] |

|||

Revision as of 21:46, 3 November 2008

RESOURCES AND WORKING DRAFTS ONLY

- United Nations Atlas of the Oceans

- Glossary of systems theory

- glossary of fishin management terms

- Definitions

- glossary of fisheries science

- FAO: Fisheries glossary

- Glossary

- of fisheries

- Category:Fish of New Zealand

- Recreational Fishing

- Fishing industry in New Zealand

- Leach, Foss (2006) Fishing in Pre-European New Zealand Joint publication by New Zealand Journal of Archaeology and Archaeofauna. ISBN 0-476-00864-6

Fishing grounds

Chatham Rise

The major submerged parts of Zealandia are the Lord Howe Rise, Challenger Plateau, Campbell Plateau, Norfolk Ridge, and the Chatham Rise.

Oceans and productivity

- The State of our Fisheries Annual summary 2006] MFish. <= NOTE

- The coast and beyond, including map of the New Zealand EEZ, from GNS Science

- New Zealand Fisheries Management Research Database

- FAO Country Profile: New Zealand

Within this zone lie rich and unusually complex seascapes with a huge variety of marine habitats and life forms. There are undersea plateaus and fishing banks, undersea mountain ranges and volcanoes, coastal estuaries and deep oceanic trenches.

The 10,000 metre deep Kermadec Trench north east of New Zealand is the second deepest trench on Earth.[1]

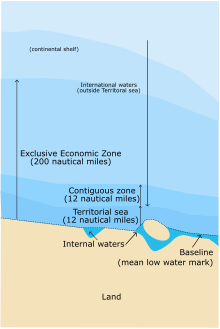

In 1978 the United Nations Conference on the Law Of the Sea (UNCLOS) extended New Zealand's territorial waters extensively (but NZ didn't ratify it until 1996). Because our outlying islands are located at favourable positions, the 200 nautical mile (370 km) circles drawn around them and the mainland's coast, neatly joined up, creating a contiguous sea area of 4.83 million square km, 15 times larger than the land. With a stroke of the pen, NZ became the fourth largest maritime country in the world. Only, France & French Polynesia, USA and Indonesia have larger EEZs. In our EEZ the fishing is reasonably good, due to currents and upwellings and a large continental shelf and continental rise (about 30% of the EEZ). Note that the area in continental shelf is often more imprtant to fisheries than the EEZ.

Tasman Sea

Tasman Sea Currents: This map shows the principles behind the currents found around New Zealand and in the Tasman Sea. The South Equatorial Current (far north of this map), which is very warm as it reaches Australia's east coast, is bent southward by Coriolis forces and by this coast. At Australia's easternmost point, it splits and one part veers east, deflected by Coriolis forces. The other half follows the east coast down until it meets cool water passing around Tasmania. On its way south, it meets the cold water of the West Wind Drift and a front or convergence forms because water masses of different temperature and salinity, mix with difficulty. In diagrams B and C, such a front is shown in a very simplified way. The front acts as a wall between the two currents that spiral along it at either side. The STF effectively walls the Tasman Sea in. Water entering it from the north, cannot pass this wall and has to exit somewhere east of New Zealand, passing by Stewart Island, through Cook Strait and around North Cape. East Australian Current[2]

The effects these currents have on New Zealand are:

- Nutrients well up along the convergence zones (TF and STF) and along the north-east coast of the North Island. It provides for good fishing.

- Nutrients are transported from Australia towards New Zealand's fishing grounds.[3]

FISHERIES & THEIR ECOSYSTEMS WEATHER EFFECTS ON PRODUCTIVITY

Westerly winds affect our ocean currents and the temperatures of surface waters. These vary between seasons and between years, and so affect the patterns of upwelling and nutrient mixing in our seas. This in turn affects how much food is available and how many fish are produced.

Like El Niño and La Niña, scientists have found links between these weather patterns, and fish abundance in a number of important fisheries. These include snapper, scallops, red cod, hoki, and rock lobster.

During La Niña years, westerly winds are weaker and plankton food sources more abundant in the Hauraki Gulf and Coromandel. These years bring the best production of young snapper and scallops in these areas.

Climate scientists think New Zealand is coming into a time of more frequent La Niña years. This may be good news for our northern snapper fisheries, but it might not be so good for other species.[4]

NZ Fisheries at a Glance

- Environment[5]

- NZ Marine Fisheries Waters: 4.4 million km2 (EEZ and Territorial Sea)

- NZ Coastline: 15,000 km

- Marine species identified: 16,000 (Environment New Zealand 2007, Ministry for the Environment)

- Species commercially fished: 130

- Area closed to bottom trawling (fisheries restrictions)

- Territorial Sea: 15%

- Exclusive Economic Zone: 32%

- Productivity of the fishery: Medium

- Ecosystems: Diverse

- Climate: Sub-tropical to sub-Antarctic

- Quote Management System Stocks[6]

- Species/species complexes in QMS: 97

- Individual stocks in QMS: 629

- Proportion of catch (by weight)from assessed stocks: 65% (Percentage of stocks calculated by weight and value, excluding squid.)

- Assessed stocks at or near target level: 85% (Remaining 15% are subject to rebuilding strategies.)

- Allowable commercial take (TACC)(Latest complete fishing years): 566,000 tonnes (October fishing year 2006/07, April fishing year 2006/07, February fishing year 2007/08. Excludes 14.95 million individual oysters, which are not measured in tonnes).

- Actual catch: 441,000 tonnes

- Commercial Fisheries and Aquaculture[7]

- Total seafood export value,2007 (FOB): $1.3 billion (Report 5A, Seafood Export Summary Report, SeaFIC based on export data supplied by Statistics New Zealand.)

- Aquaculture exports: $226 million (Mussel,salmon and oyster exports for the calendar year 2007)

- Total seafood exports,2007: 315,600 tonnes

- Total quota value: $3.8 billion (Statistics New Zealand.Fish monetary stock accounts, 1996-2007)

- Persons with quota holding: 1,617

- Commercial fishing vessels: 1,316

- Processors and Licensed Fish Receivers: 229

- Direct employment (full time equivalents): 7,155 (Census 2006)

- Cost recovery levies (fisheries services)and user fees,

2008/09 (planned): $35 million

- Customary Fisheries[8]

- Tangata Tiaki appointed (South Island): 107

- Tangata Kaitiaki appointed (North Island): 209

- Temporary closures: 5

- Taiapure-local fisheries: 8

- Mätaitai reserves: 7

- Customary take provided for within the TAC: 4,802 tonnes

- Recreational Fisheries[9]

- Estimated participation (as a %of the total NZ population): 31% (Andrew Fletcher Consulting Survey, November 2007. Prepared for Ministry of Fisheries)

- Estimated annual take: 25,000 tonnes (1999/00 Survey of Recreational Fishing)

- Ministry of Fisheries[10]

- Budget 2008/09 (excl GST): $94.5 million

- Net assets: $12.6 million

- Staff (March 2008)(FTEs): 432

- Honorary Fishery Officers (March 2008): 165

- Observers (March 2008): 57

Current fisheries

- Deep-water fisheries

is 15,134 km long.

The Quota Management System

A new system: By the early 1980s, with dwindling inshore stocks and too many boats, the New Zealand fishing industry and the government realised that a new fisheries management system was needed. Measures such as moratoriums and controlled fisheries failed to work. The common warning that ‘too many boats are chasing too few fish’ was rephrased by one fisherman as, ‘too many boats chasing no fish’. Radical thinking emerged. For decades fishing had been dominated by the belief that the sea teemed with fish, and that stocks could not be affected by fishing. As catches dropped alarmingly such views were abandoned. Fisheries management began to adopt a revolutionary approach – instead of controlling fishing methods and the number of boats the goal became limiting how many fish were caught. In October 1986, after two years of consultation and planning, the Quota Management System was introduced, with widespread industry support. When fishers became aware that a quota system was to be introduced, they increased their activity – quotas (how much fish a person or company is allowed to catch) were allocated on the basis of catch history.[11]

How the quota system works: Previously the fish in the sea could be caught by anyone who had a licence and complied with other regulations. Under the quota system a sustainable total catch or harvest of fish was set. Individuals or companies were allocated the right to catch certain quantities of particular species. Quotas became like other forms of property – they could be leased, bought, sold or transferred. While there has been much tinkering with the system, its basis remains the same. Each year scientists and the industry together assess the population of all major fish species. Set quotas (in kilograms) are allocated annually to individuals or companies. In theory no one is allowed to catch more than their quota, and all the quotas add up to the total allowable catch. In practice, as fishers cannot control how much their nets scoop up, they can actually catch more than their quota – but this has to be paid for. In some fisheries non-commercial use is significant (for example, by Māori harvesters and recreational anglers) and this is taken into account before the total allowable catch is set.[12]

Species under the system: Since 1986 the Ministry of Fisheries has steadily been bringing all commercial species under the management of the quota system. In 2005 there were some 93 species (or groups of similar species) managed under the system. Species were further split into about 550 distinct stocks based on where they occur.[13]

- The quota system – an evaluation

New Zealand’s Quota Management System has been viewed internationally as successful. This is particularly in comparison with many of the world’s fisheries where there is still an open-season approach (whereby regulations are placed on fishing days and equipment, rather than on limiting the total catch). Although some fish stocks have been over-exploited, New Zealand has (so far) largely avoided the significant stock collapses that have occurred in fisheries overseas. In the early 2000s the Ministry of Fisheries had records on the status of 60–70% of stocks. Of these, about 80% were at or near target levels for sustainable harvest, and the total allowable catch for some fish had even increased.Fishing industry Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007</ref>

Fishing down: The remaining 20% of fish species are in decline or remained depleted. This does not necessarily mean that these fisheries are collapsing – a stock is often ‘fished down’ to a level that produces the maximum sustainable yield. A stock of fish that has never been harvested is dominated by older, larger fish. When a stock is first fished, the removal of the large fish allows more food for younger fish, and as they grow faster, the total biomass (weight) of the harvestable stock increases. This process is termed ‘fishing down’ as the stock is reduced to a level that allows the maximum weight of fish to be harvested while still retaining enough individuals to allow a similar level of harvest in future years. ‘Fishing down’ alters the population structure from one which is old and slow-growing to one dominated by young, fast-growing individuals. Despite the relative success of the quota system, difficult issues remain.Fishing industry Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007</ref>

How many fish should be caught?: Setting quotas for individual species is problematic. To determine how many fish can be taken from a population, scientists have to estimate how many fish there are and how quickly they reproduce. They then attempt to determine the maximum sustainable yield, which is an estimate of how many individual fish can be removed from a population without the stock going into an ongoing decline. If numbers fall too low, then quotas are immediately cut. Populations and quotas are determined using various methods, such as research surveys, catch monitoring, ships’ logs, landed catches and computer modelling. However, these calculations are not always reliable, as declines in some oreo and orange roughy stocks have proven. This is particularly true with deep-sea stocks. Little is known about some species, and their populations can be overestimated.Fishing industry Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007</ref>

Politics: In 2004 the New Zealand fishing industry employed some 26,000 people and was worth a billion dollars in export revenue. With so many jobs and investments at stake, fisheries management, including the quota system, can be political, and major disagreements are often only settled in court.[14]

Research

Research is often difficult to undertake and expensive. Each year research is undertaken for only a small proportion of the 629 individual geographical management units that exist in the quota management system. There is sufficient information to characterise stock status for 85 of the main commercial stocks. Of these 72 (85%) are at or near target levels. These represent the main commercial stocks. Rebuild strategies are in place for the remaining 13 stocks.

The aquatic environment is a complex system consisting of a vast area and over 8,000 species. Complete information about every aspect of the aquatic environment or even the most important species is never going to exist, no matter the amount of research undertaken or money expended. One of the consequences of limited information is that certain assumptions about the state of some fisheries, based upon the best available information at the time, have been found in hindsight to be incorrect. The result is that some fish stocks have been reduced to levels sufficiently low enough to require them to be closed to fishing to help ensure their sustainability.[15]

The traditional way to manage fisheries is to focus on a single species - determining how many can be caught without affecting the breeding population and causing harm to the species fishery. However, taking any fish affects the other marine life that eat them, and that in turn affects the marine life that eat the marine life that eat them, and so on up the chain. Scientists from NIWA are working their way through more than 40,000 fish stomachs, to learn about the diets of different species across the Chatham Rise. When these are combined with similar diet studies for sea mammals and birds, and with other climate and ocean studies, there will be a better picture of how different parts of the Chatham Rise ecosystem fit together.[16]

Wild fisheries

Crayfish

2007 quota $(NZ) 621m Crayfish Spiny lobster Parastacidae Kaikoura Jasus Chatham Islands The Catlins Southern koura Northern koura

|

Scampi

Metanephrops challengeri

Scampi

|

Crabs

|

Paua

Paua'2007 quota

|

Pipi

|

Kina

|

Scallops

|

Bluff oysters

Oysters One heavily modified stretch of sea floor is Foveaux Strait, where oyster boats have dragged their dredges for over a century. The sorts of plant and animal communities that develop on the sea floor there are those that can survive this sort of regular disturbance.[34]

|

Toheroa

|

Flatfish

Flatfish Rhombosolea leporina R. plebeia R. retiaria R. tapirina Pelotretis flavilatus Peltorhamphus novaezeelandiae Colistium guntheri C. nudipinnis

|

Arrow squid

Squid

|

Colossal Squid

Kelp

|

Whitebait

|

Snapper

Snapper2007 quota

|

Orange roughy

Orange roughy

|

Kahawai

Kahawai

Kahawai are a schooling pelagic species belonging to the family Arripididae. Kahawai are found around the North Island, the South Island, the Kermadec and Chatham Islands. They occur mainly in coastal seas, harbours and estuaries and will enter the brackish water sections of rivers. A second species, A. xylabion, has been described (Paulin, 1993). It is known to occur in the northern EEZ, at the Kermadec Islands and seasonally around Northland.[62]

|

Barracouta

Barracouta

|

Trevally

Trevally (Pseudocaranx dentex)

|

Jack mackerel

Jack mackerel

|

Tarakihi

Tarakihi The tarakihi (Nemadactylus macropterus) is found throughout New Zealand. It feeds below 25 metres, scavenging worms, crabs, brittle stars and shellfish from the bottom. At night it rests on the sea floor, where its colouring becomes blotchy. From the mid-1940s the annual commercial catch was around 4,000–6,000 tonnes, but this has declined.[74]

|

Red gurnard

Red gurnard

Hoki

Ling

Hake

Oreo

Toothfish

Greenshell mussel

Pacific oysters

King salmon

Organisations

Māori roleMāori commercial fisheries settlement: The biggest change since the quota system was introduced in 1986 has been the emergence of Māori as a major industry player. This occurred when the Crown settled Māori commercial fishing claims under the Treaty of Waitangi. In 1989 an interim agreement was reached, and the Crown transferred 10% of the quota (some 60,000 tonnes) together with shareholdings in fishing companies and $50 million in cash to the Waitangi Fisheries Commission. This commission was responsible for holding the fisheries assets on behalf of Māori until an agreement was reached as to how the assets were to be shared among tribes. In 1992, a second part of the deal, referred to as the Sealord deal, marked full and final settlement of Māori commercial fishing claims under the Treaty of Waitangi. This included 50% of Sealord Fisheries and 20% of all new species brought under the quota system, more shares in fishing companies, and $18 million in cash. In 2003, agreement was reached as to how the assets would be shared. Over 90% of tribes agreed with a proposal that held 50% of assets centrally and allocated the rest directly to tribes based on coastline length and tribal populations. In 2004 a governance body, Te Ohu Kaimoana, was set up to oversee all Māori commercial fishing settlement assets. Since 1992 the value of these assets had tripled in value, to around $750 million in 2004. About $350 million, representing around a third of New Zealand’s commercial fishing industry, was to be administered under a company called Aotearoa Fisheries.[102] Conservation and sustainabilityGlobally, the omens do not look good. Everywhere, there are signs of the environment’s limits being stretched. The global fish catch has now reached the limits of our ocean’s fisheries. And these limits are being stretched as some marine ecosystems and habitats are damaged or destroyed by fishing and pollution. Our oceans and their ecosystems are hugely complex affairs, and we struggle to understand a tiny fraction of them. So the government is naturally cautious whenever it sets catch limits for fisheries. It is also naturally cautious when it deals with the effects of fishing on threatened seabirds and marine mammals, or on habitats and ecosystems.[103]

There has recently been growing concern about the effects of bottom fishing on seafloor habitats. Fragile bryozoan beds on the sea floor in Tasman Bay and Spirits Bay have already been closed to bottom fishing, as have some 19 deep-water seamounts. The government is now looking at the effects of bottom fishing on other habitat types.[104] Fisheries managers still do not have enough information to know if trawling affects the ecosystems of seamounts. The Fisheries Act takes a precautionary approach; for instance 19 seamounts were closed to bottom trawling in 2000; and in 2006 a draft agreement was reached to close another 30% of the Exclusive Economic Zone to bottom trawling.[105] About 35% of our EEZ lies in trawlable depths (0–1500 m). Much of the shallower parts will have been fished at some point, but some depths and certain fishing grounds are fished often. In places like these, the sea floor today will likely be different to what it once was. One heavily modified stretch of sea floor is Foveaux Strait, where oyster boats have dragged their dredges for over a century. The sorts of plant and animal communities that develop on the sea floor there are those that can survive this sort of regular disturbance.In shallow waters, some types of sea floor communities can recover quite quickly from the effects of dredging or trawling. But fragile deepwater habitats may take hundreds of years to recover from such effects. The government has already closed a number of areas to bottom fishing. The catches in most of our major fisheries are set close to the maximum sustainable level. [106]

In May 2001 the New Zealand hoki fishery became the world's first whitefish stock to achieve Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification. This eco-label is independent confirmation that the New Zealand hoki industry is well managed according to the principles and criteria of the MSC. Currently only 22 seafood suppliers world wide have obtained this certification standard for sustainable and managed fisheries. A key principle of the certification is to assess the impact of the fishery on the marine ecosystem, and the certification report on the Hoki industry required the industry to carry out further research and risk assessment work to accurately assess the impact of the fishery on the marine environment. The certification report indicated that within the fishery there is an occasional incidental by-catch of seals and seabirds but that a formal compulsory programme to control this by-catch is in place. The certification required the industry to carry out further research and to continue to develop new technology and modify fishing practices to reduce incidental by-catch of both seabirds and fur seals.[107]

HistoryPolynesian settlers

New Zealand is an ancient land which has only recently felt the imprint of human beings. The human history of New Zealand starts about seven hundred years ago when it was discovered and settled by Polynesians. They arrived in ocean going canoes, or waka, cira 1300. The descendants of these settlers became known as the Māori, forming a distinct culture centred on kinship links and land.[108]  Subsequently smaller unornamented canoes (waka tīwai) were used for fishing and river travel. These were the earliest fishing vessels used in New Zealand. In Māori mythology, a culture hero called Māui went fishing in his canoe. Using a jaw-bone fashioned as a fish hook and blood from his nose for bait, he hauled a great fish from the depths. Māui then went to find a priest to perform theappropriate ceremonies and prayers, leaving his brothers in charge of the fish. They, however, did not wait for Māui to return but began to cut up the fish. The fish writhed in agony, and broke up into mountains, cliffs and valleys. This fish became the North Island of New Zealand, and is known to the Maori as Te Ika-a-Māui (The Fish of Māui). If the brothers had listened to Māui the island would have been a level plain and people would have been able to travel with ease on its surface.[109] In Māori traditions from the South Island of New Zealand, Māui’s canoe became the South Island, with Banks Peninsula marking the place supporting his foot as he pulled up the extremely heavy fish. Therefore, besides Te Wai Pounamu, another Māori name for the South Island is "Te Waka a Māui" (The canoe of Māui). European settlersThe first documented European explorer arrived in New Zealand over 300 years later, in 1642. From the late 18th century, the country was increasingly visited by British, French and American whaling, sealing and trading ships. In 1841 New Zealand became a British colony followed by a period of European immigration and land wars. New Zealand gradually became more self-governing and achieved the relative independence of a dominion in 1907. The first European known to reach New Zealand was the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman, who arrived in his ships, Heemskerck and Zeehaen, in 1642. Over 100 years later, in 1769, the British naval captain James Cook of HM Bark Endeavour made the first of his three visits. Cook produced, for the times, remarkably accurate maps of the New Zealand coastline. On 15 November 1769 Cook's crew caught about one hundred fish near the entrance to Whangarei harbour which they classified as "bream" (probably snapper). This prompted Cook to name the area "Bream Bay".[110] Early research In 1872 the sailing ship HMS Challenger undertook one of the greatest voyages of biological discovery. For three and a half years it circumnavigated the globe, taking soundings and putting down dredges and trawls. New Zealand waters were included in this amazing voyage. The later named Challenger Plateau, west of New Zealand in the Tasman Sea, was located and studied, and New Zealand marine biologists James Hector and Frederick Hutton described some of the fish collected there. The result of the project was the discovery of 4,717 new species globally, and a greater understanding of the depths. No further study of the deep sea around New Zealand was undertaken until the 1950s when a retired fisherman, Richard Baxter, managed to catch the lantern dogfish (Etmopterus baxteri), white rattails and basketwork eels. He used a hand line down to 1,000 metres from an open dinghy off Kaikōura. It was not until the 1970s that exploratory trawling began in depths of 800–1,000 metres. This was quickly followed by commercial trawling of orange roughy, a deep-sea fish. Today, although we have some understanding of the creatures that live in the depths, there is evidence that a vast number of organisms remain unknown. The first intact specimen of the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) was discovered as recently as 2003, south of New Zealand in the Ross Sea. This 6-metre specimen was a juvenile; scientists speculate that adult forms could be two or three times larger.[111] Coastal fishing

Māori were the first fishers – they depended largely on fish and shellfish for protein. When European sailors brought over pigs in the late 1700s, there was suddenly a ready supply of meat on land. Sheep and cattle followed in the 1800s. European settlers saw little need to fish when there was so much food on the land.Many British migrants were reluctant to eat fish because they considered it fit only for poor people. They were also unfamiliar with New Zealand’s fish species. They named many of the fish they found after what they knew – cod, mullet and herring. Although the sea around their new homeland teemed with fresh seafood, the British imported cured, salted and canned fish from home.[112] Small-scale fishing: Until the Second World War the New Zealand fishery was characterised by little fleets of small vessels. Boats were owner-operated, and they sailed from a number of ports supplying local markets. Exports were minor. The Wellington experience is typical of the early fishing scene in New Zealand. In the mid to late 1800s Shetlanders, Italians, English and French fetched up on Wellington’s shores and soon realised what Māori had long known – Cook Strait abounded with blue cod, snapper, groper, warehou and crayfish. Fishing settlements sprang up, creating distinct communities at Paremata, Makara, Island Bay and Eastbourne. In the South Island, small craft worked inshore fisheries such as Otago Harbour, which served the growing city of Dunedin. Small-scale family operations dominated the fishing scene for decades. Prior to refrigeration, fish-curing sheds and smokehouses were built at small ports around the coast. Oysters were an early boom-and-bust fishery. Both rock and dredge varieties were exported in their millions over the 1880s, but by the 1890s beds were stripped and the fishery collapsed.[113] Selling fish: In the early days, fish had to be distributed quickly, before it spoiled. Fish hawkers would take fish into towns on horse-drawn carts, calling out their wares and selling it door to door. Once ice could be made, fish was displayed in shop windows. One fishmonger had a penchant for gimmicks. At Hurcomb’s in Cuba Street, Wellington, a penguin was stationed at the door and fed fish, which would disappear in one neat gulp.[114] Pakeha New Zealanders were not great fish eaters in the early days. In 1914, for example, New Zealanders ate only 2 kg per person per year. Today we eat more than 10 times that amount. What put them off their fish?

Refrigeration: Although fish-curing and canning plants had been trialled, the fishing industry remained small until the advent of refrigeration. Refrigerated shipping allowed the first consignment of frozen fish to be exported – some 16 tonnes were sent to Sydney in 1890. With refrigeration came ice making, and fishmongers displayed the catch of the day on beds of ice in their shop windows. On shore, fish could be kept frozen in isolated places far from markets. Freezers appeared at localities as remote as Port Pegasus in southern Stewart Island. However, refrigerated space was often limited, and there was nowhere to store over-supplies. Irregular shipping services and poor roads made it difficult to transport seafood to markets. Once rail services were established, fish could be transported quickly and easily. This proved important for port towns such as Ōamaru, which sent its fish to Christchurch and Dunedin. From Napier, wagons of fish trundled down the line to Wellington. However, it took time for refrigeration to become established. Only in the 1930s did refrigerated space became widely available, allowing a small export industry to develop. In addition, different fish species needed different cool or freezing conditions to maintain their quality, and it took time for this knowledge to develop. [116]

Crayfish: During the 1940s the New Zealand government began to apply a moderate amount of fisheries regulation. Growth was slow but the industry was stable, with fin fish selling mainly on the domestic market. Crayfish (rock lobster), caught from the rocky Kaikōura and Fiordland coasts, became increasingly important, and by 1963 accounted for close to 70% by value of fishing exports. Crayfish from the Chatham Islands became big business in the late 1960s. When frozen lobster tails began to be shipped to the United States, many fishers realised that fishing was not solely a domestic business – it could be a lucrative export industry. The notion that fish could be exported was not new. What was new were reliable transport links and the high price paid for fish. These factors revolutionised the business of catching fish.[117] Inshore growth: Until the mid-1960s about half a dozen species dominated New Zealand catches. These were snapper and tarakihi (about half of total landings), gurnard, trevally, blue cod, elephant fish, flounder and sole. The industry had survived by catching only about a sixth of the commercial fish varieties found close to shore. In the mid-1970s government export incentives boosted the industry, which invested in more and bigger boats. These targeted barracouta, kahawai, mackerel, pilchards, trevally, red cod, warehou, and squid. New technologies such as depth sounders, radar, sonar, and new fishing gear boosted the numbers of fish caught. But it was still essentially an inshore fishery. Large foreign vessels that fished offshore had first arrived in the late 1950s. They were unpopular with local fishers, but they did alert them to the abundance of fish in deeper waters. At this time New Zealand’s territorial waters extended only 3 nautical miles offshore. This was extended to 12 nautical miles in 1970, but anything beyond this imaginary line was open to all comers.[118]

Netting and hand lining: New Zealand fishing in the late 1880s usually involved setting nets in harbours and estuaries. Trawling (dragging a net along the sea floor) was introduced in 1900, and Danish seining (encircling schooling fish with a net) in 1923. But even with these innovations the commercial fishing scene in the early 20th century was dominated by small-scale line and set-net fishing.[119] Boats: Many fishing boats were built by the fishers themselves. Shetlanders such as Fraser and Moat in Wellington built distinctive boats based on their island craft – sharp at both ends with bow and stern curving upward. Small wooden boats powered by oars and sails were rarely taken into the open sea. In Otago Harbour, fishermen did not fish beyond the heads until the advent of small, mainly single-cylinder engines in the early 1900s. The principal make was the Frisco Standard, and these engines were powered by benzene sold in cases with brand names such as Plume and Big Tree. Vessels were small, lacked radios, had low-powered and often unreliable engines, and poor life-saving equipment. Fishing was a dangerous business and unlucky fishermen lost their lives. Many others had close shaves when sudden gales blew up and they had to hastily retreat to shore.[120] Hauling: Fishermen needed to be strong – before the widespread introduction of winches in the late 1920s and early 1930s nets, supplejack cray pots and lines all had to be hauled in by hand. In places such as Kaikōura the fishermen were used to sore hands and bad backs.[121] Trawling: In the 1920s and 1930s coastal trawling out of Lyttelton was conducted by 15–18-metre wooden vessels powered by small engines and crewed by two men. They targeted species such as tarakihi, flounder and sole, but much of the by-catch (untargeted species) was dumped as it could not be sold – consumers were very fussy about which fish species they would eat. Vessels mainly fished close to shore and out to the continental shelf, but would rarely trawl deeper than 90–130 metres.[122] Laws and licences: Many fishers were part-timers and there were few government controls or regulations. It was a small, domestic industry with no sustained exports of any great value. Various regulations such as the ability to close fisheries and restrict net-mesh sizes had existed since the Fish Protection Act 1877, and these were pulled together under the Fisheries Act 1908. Entry into fishing was not stringently controlled until the late 1930s, when fishing became licensed and the number of vessels was restricted.[123] Dog barking navigation: Skippers of early fishing vessels made do with compasses, charts (often inaccurate), sounding lines, and their knowledge of the sea. When fog came down on the coastal trawler Dolphin off the Canterbury coast in the 1920s, getting to shore meant listening for barking sheepdogs: "We were fortunate to catch a glimpse of Pompeys’s Pillar off the peninsula and carried on by what we called "dog barking navigation" right around the peninsula … Next morning we heard that the coastal steamer Gale had hit the outlying rock off Akaroa South Head and that The Breeze had hit the shore in Pegasus Bay".[124]  Hazards: To protect moored fishing boats from storms, breakwaters were built in areas where there was no natural port. In many other locales boats were ramped up onto beaches and hauled up on custom-built slipways, or they were kept in boathouses. Wharves were built to help land the catches and to deal with other supplies. The sea water around New Zealand is cold and fishermen lost overboard do not last long before hypothermia kills them. Many fishermen have died in this way. The social cost of fishing has been high – many children have lost their fathers, and wives and mothers have waited at home worrying while their husbands and sons ride out the storms.[125] Navigation: Navigational aids were rudimentary at first. The position of a boat at sea was determined by lining it up with known landmarks. Later, in places such as Kaikōura, white diamond-shaped markers were built on wooden poles on hills to guide boats into the harbour. When electricity became available these were replaced with lead lights. Lighthouses were built around the coast to help keep fishing boats off the rocks.[126]

Export boom: Licensing of fishing boats was discontinued in New Zealand in 1963, along with some other regulations, and this opened up the fishery to new participants. However, many restrictions on fishing methods and fish size remained in force. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s there was increasing growth in exports dominated by shellfish and crayfish. Fishing companies such as Sanford in Auckland, Sealord Products in Nelson, and Watties in Gisborne became major players in the industry. Bigger steel boats replaced smaller, traditional wooden vessels, and onshore fish-processing plants were built. During the late 1970s the industry boomed, with rapid growth in fin-fish catches. Fish exports were only 14,000 tonnes in 1975; six years later, 129,000 tonnes were being exported. The exponential growth in the total catch could not be sustained, however, and it crashed in the 1980s. Coastal fisheries had become fully exploited and too many boats were chasing too few fish. In 1983 it was estimated that a reduction of 294 vessels was required to balance the numbers of inshore fish available with the number of vessels fishing for them. The government intervened. From 1978 no new fishing licences for crayfish and scallops were issued, and from 1980 a moratorium was placed on permits for fin fish.[127] The tip of the iceberg?: In the late 1960s the fishing industry turned its attention to open-water schooling fish such as kahawai. A spotter plane surveying these fish off the Nelson coast had a surprising finding: "A geological survey explosion by an oil company was observed on 1.4.69. Prior to the explosion two shoals of “kahawai” were noted in the area; after the explosion a further 14 shoals came up to the surface …This incident gave rise to an important question: How much of the total fish population do the surface fish shoals represent?"[128] Towards radical change: As this crisis developed in the coastal fisheries, two developments opened up a way forward:

These two changes would transform the fishing industry over the next 20 years. [129] History of fishing in New Zealand2

Throughout the 19th century and early 20th century, New Zealand's commercial fishing developed quite slowly. It was limited to inshore fishing grounds and was localised and small scale, using small boats, catching most fish by line or set nets. In 1900, trawling was introduced, and in 1923, Danish seining (see Fact sheet, Fishing Methods). However even at that time, there were concerns about the effect of these new fishing methods on fish stocks, and after pressure from recreational fishers and commercial fishers some fishing areas were closed to these new fishing methods. Species Last century, many of the fish species we value today, such as gurnard, red cod and even rock lobster, were held in poor regard. On the other hand, species like flounder, mullet and blue cod were very popular. While there are about 1000 known fish species in New Zealand waters, only about 100 - 200 of these are caught commercially, and, of these, only about 25 - 30 species are important. The popularity of the various species is changing. A few years ago we were even more choosy about the fish we caught. For example, in 1969, 81.4 percent of the fish landed were from just 10 species. The top three species were snapper (34.8%), tarakihi (11.0%) and trevally (10.0%) Today, the spread of species is more even and slightly wider, and there are now 40 or so major commercial finfish species including orange roughy and hoki. The main changes in the last 20 or so years have centred around: ∑ deepwater species such as hoki, orange roughy and southern blue whiting ∑ pelagic (surface feeding) species like tuna, mackerels and kahawai ∑ shellfish like paua, rock lobster and squid; and aquaculture (mussels, oysters and salmon) Rules and regulations From 1860 onwards, various regulations were put in place to prevent overfishing. In 1908, the rules were consolidated into a Fisheries Act. It stayed in force until 1983, although it was changed many times along the way. Since that time there have been a number of amendments - the most significant of which were in 1986 to introduce the Quota Management System, and in 1996 when the new Fisheries Act was passed. By and large, fishing wasn't controlled in New Zealand until the late 1930s, when industries, including fishing, became licensed. The number of vessels was restricted to conserve fish stocks, although at the time there was little scientific evidence to justify this. From the late 1950s, foreign fishing boats started coming into our waters (at that stage our territorial waters extended just three miles offshore). Exports of rock lobsters to the United States had begun, and this also showed something of the potential for growth. There was pressure to free up access to fisheries, and in 1963 the fishing industry was almost completely deregulated. Financial incentives were brought in by the Government to encourage investment. Over the next 15 years the industry grew, but too many boats were chasing the same species. Companies were unwilling to invest in "unknown" deepwater fisheries and mainly stuck with the inshore fisheries they knew. By the late 1970s, many fishers were going out of business as their catch rates declined. By this time, foreign vessels were taking huge tonnages from the deeper waters around New Zealand. Quantity of catch In the last 20 years the quantity of fish caught in New Zealand waters has jumped dramatically, for several underlying reasons: ∑ From the 1960s through to the late 1970s there was a rapid increase in the level of foreign fishing activity in waters around New Zealand. This peaked just before the declaration of the 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in 1978. Catches fell away again sharply after the Government cut back the level of foreign fishing, but picked up again as New Zealand companies got involved ∑ In 1963, fishing was deregulated and new investment encouraged ∑ The Quota Management System was introduced in 1986. Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs) were to be allocated on the basis of catch history, so there was something of a scramble among commercial fishers immediately beforehand, to build up a sizable catch history. This helped inflate catch figures for the mid 1980s. Catch levels dropped away again once ITQs were introduced. The introduction of the 1996 Act is not expected to cause any major change in the quantity of fish caught. International conventions New Zealand fisheries managers are required to take account of several international conventions when developing fisheries policies. The major convention is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This convention enabled New Zealand to establish an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles. Within the EEZ, New Zealand is responsible for managing fisheries on a sustainable basis. Another example is the international Biodiversity Convention which New Zealand signed in 1992. This requires us to conserve the diversity of biological systems and manage their use in a sustainable way to avoid the loss of genetic material. The EEZ In 1978 New Zealand declared its 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone. This led to some control over foreign fishing. Foreign vessels were licensed and given quota for the main species. Since then, direct foreign involvement in New Zealand fishing has declined to almost nil as New Zealand companies have moved into deepwater fisheries. However, many of the foreign vessels remained, fishing under joint venture or charter arrangements with New Zealand companies. By the late 1970's some inshore fisheries were showing signs of stress, and for this reason, no new rock lobster and scallop fishing permits were issued from 1978, and in 1980 there was a moratorium on issuing new licences for catching finfish. In 1983 a new Fisheries Act was passed which allowed for the development of Fisheries Management Plans, for better regional management of fisheries. The Act also excluded part-time fishers from the industry. Commercial fishers had to be earning more than $10,000 a year, or 80 percent of their income from fishing, to remain licensed. In the same year a Deepwater Enterprise Allocation system was introduced, which allocated quota for some species for a limited period. This was a forerunner to today's Quota Management System. (For more on the Quota Management System see the Fact Sheet, How we conserve our fisheries.) Enforcing the rules Input controls = controlling how fish are caught Output controls = controlling how many fish are caught Until the 1980s, the emphasis was always on input controls, that is, controlling the way fish were caught. For example, there were rules on the number of boats that could fish, net size and so on. However, this type of rule was not very good at conserving fish stocks, because modern technology always found a way to catch more fish within the existing rules, for example, using bigger and more powerful boats. For this reason, a system controlling outputs - the quantity of fish caught - was introduced. The Quota Management System was fully introduced in 1986 through a major amendment to the 1983 Act. This fully established the concept of Total Allowable Catches and defined a process for bringing species into this management system. In 1996 this was further refined a with new Fisheries Act which has been introduced over several years. On 1 October 2001 the remaining parts of this Act were introduced. The level of enforcement of rules has been substantially increased. In 1914, the entire country was policed by only 20 fisheries wardens. Today, the Ministry of Fisheries polices the Quota Management System through about 100 enforcement officers, with a further 400 honorary fisheries officers assisting MFish in policing the regulations covering recreational fishing. Research Little fisheries research was carried out around New Zealand until the 1960s. As early as 1900 the Government of the day commissioned trawl surveys around the coast to identify fishing grounds and offshore banks. One such survey was carried out by the Nora Niven, which could trawl as deep as 350 metres. It eventually surveyed the entire coastline of both islands. Before 1965, most fisheries research concentrated on freshwater species, but since then the emphasis has changed. Marine research was handled by the former Marine Department until 1972, when the Fisheries Division became part of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. The Ministry's ability to carry out research was hampered by the lack of suitable research vessels, so in 1969 it bought the 500 tonne stern trawler, James Cook. This boosted research capabilities, but could not really explore the increasingly important deepwater fisheries, so the Ministry depended largely on chartered trawl surveys and joint venture research until 1991 when the state-of-the-art research vessel, "Tangaroa", came into service. More recently the Ministry's role has changed to one of contracting out its research requirements. These encompass fisheries biological research and also, research into environmental issues as they relate to fisheries, for example, the impacts of fishing. For more on the Ministry of Fisheries' research programmes today, see the Fact sheet, Marine Fisheries Research.[130] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- ^ Fisheries and their ecosystems. NZ Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Seafriends: Why is New Zealand so special?

- ^ Seafriends: Why is New Zealand so special?

- ^ Fisheries and their ecosystems. NZ Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries: NZ Fisheries at a Glance Retrieved 11 June 2008

- ^ New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries: NZ Fisheries at a Glance Retrieved 11 June 2008

- ^ New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries: NZ Fisheries at a Glance Retrieved 11 June 2008

- ^ New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries: NZ Fisheries at a Glance Retrieved 11 June 2008

- ^ New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries: NZ Fisheries at a Glance Retrieved 11 June 2008

- ^ New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries: NZ Fisheries at a Glance Retrieved 11 June 2008

- ^ Walrond, Carl. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Walrond, Carl. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Walrond, Carl. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Status of New Zealand Fisheries

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ecosystemswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Red Rock lobster

- ^ Minister congratulates crayfish industry

- ^ rock lobster (crayfish)

- ^ CRAYFISH

- ^ Crayfish or rock lobster?

- ^ Crayfishing: Early years

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Scampi

- ^ Scampi

- ^ Crabs

- ^ Walrond, Carl. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Paua

- ^ {Paua: Sustainable fisheries within a healthy aquatic ecosystem

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Pipi

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Kina

- ^ Kina

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Queen scallop

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Scallop

- ^ Fisheries and their ecosystems. NZ Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Dredge oyster (Foveaux Strait)

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Dredge oyster (Other)

- ^ Bluff keeps oyster festival after community rallies - The New Zealand Herald, Thursday 13 December 2007

- ^ "Shellfish Fisheries" (PDF). Ministry of Fisheries.

- ^ Dredge oysters

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Flatfish

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Arrow squid

- ^ Squid fishing

- ^ Traditional use of seaweeds

- ^ [http://www.teara.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/SeaLife/Seaweed/5/en Modern uses and future prospects

- ^ Coastal predatory open-water fish

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Snapper

- ^ Explanation of Growth Overfishing

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fishing_lure

- ^ http://www.squidgy.com.au/pro_range/index.html

- ^ Glossary of Terms 2

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Orange roughy

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Orange roughy

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Orange roughy

- ^ Darby, Andrew (2006-11-10). "Trawled fish on endangered list". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ [[1]]

- ^ "Case for trawl ban 'overwhelming'". BBC New. 2007-05-5. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Beehive - NZ and Australia close orange roughy fishery

- ^ Paddy Ryan. Deep-sea creatures. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Robertson, D A (1990) The New Zealand orange roughy fishery: an overview. In Issues and opportunities: proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand southern trawl fisheries conference, Melbourne, 6–9 May 1990, edited by K. Abel and others. Canberra: Australian Government Printing Office, 1991, p. 38.

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Fishbase: Hoplostethus atlanticus (Orange roughy)

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Kahawai

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Kahawai

- ^ Coastal predatory open-water fish

- ^ Coastal predatory open-water fish

- ^ Plankton-feeding open-water fish

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Barracouta

- ^ Plankton-feeding open-water fish

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Trevally

- ^ Plankton-feeding open-water fish

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Jack mackerel

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Jack mackerel

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Jack mackerel

- ^ Fish of the open sea floor

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Tarakihi

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Tarakihi

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Tarakihi

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Tarakihi

- ^ Fish of the open sea floor

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Red gurnard

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Red gurnard

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Walrond, Carl. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Hoki

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Hoki

- ^ Paddy Ryan. Deep-sea creatures. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Fishing for hoki

- ^ LING

- ^ Paddy Ryan. Deep-sea creatures. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Ling

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Haki

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Oreo (black)

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Oreo (smooth)

- ^ NZ Ministry of Fisheries: Toothfish

- ^ "Toothfish at risk from illegal catches". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-02-11.

- ^ "Toothfish". Australian Government Antarctic Division. Retrieved 2006-02-11.

- ^ Paddy Ryan. Deep-sea creatures. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Marine aquaculture

- ^ Marine aquaculture

- ^ Marine aquaculture

- ^ Marine aquaculture

- ^ Walrond, Carl. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Fisheries and their ecosystems. NZ Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Fisheries and their ecosystems. NZ Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Walrond, Carl. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Fisheries and their ecosystems. NZ Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Accidental by-catch. NZ Seafood Industry Council. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- ^ Sutton, Douglas G. (Ed.) (1994). The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- ^ (Tregear p 234)

- ^ A. H. Reed (1968). Historic Northland.

- ^ Exploration of the deep

- ^ Carl Walrond. [http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/HarvestingTheSea/FishingIndustry/en Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. [http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/HarvestingTheSea/FishingIndustry/en Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. [http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/HarvestingTheSea/FishingIndustry/en Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ ssss

- ^ Carl Walrond. [http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/HarvestingTheSea/FishingIndustry/en Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007 URL:

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007 URL:

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 Sep 2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 Sep 2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 Sep 2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 Sep 2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 Sep 2007

- ^ G. Brasell, G (1991) Boats and blokes. Wellington: Daphne Brasell, p 52.

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 Sep 2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 Sep 2007

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ Webb, B. F. (1971) Survey of pelagic fish in the Nelson area, 1968–69. Fisheries Technical Report 69. Wellington: New Zealand Marine Department, p 13.

- ^ Carl Walrond. Fishing industry. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21-Sep-2007

- ^ ssss