Green economy: Difference between revisions

Paul Safonov (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

poly 141 188 139 173 143 147 152 126 169 107 191 88 216 75 242 65 280 55 310 53 352 54 379 60 415 71 447 88 461 99 475 112 488 128 496 147 500 162 500 176 500 189 471 185 452 183 410 185 369 194 337 206 319 216 305 208 279 197 257 191 230 185 199 183 199 182 199 183 [[Society|Social]] |

poly 141 188 139 173 143 147 152 126 169 107 191 88 216 75 242 65 280 55 310 53 352 54 379 60 415 71 447 88 461 99 475 112 488 128 496 147 500 162 500 176 500 189 471 185 452 183 410 185 369 194 337 206 319 216 305 208 279 197 257 191 230 185 199 183 199 182 199 183 [[Society|Social]] |

||

</imagemap> |

</imagemap> |

||

A '''Green Economy''' is one that results in improved human will-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. |

|||

- United Nations Environment Programme (2010) |

|||

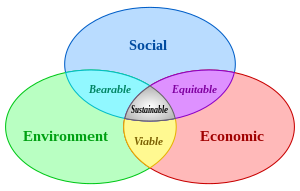

A '''green economy''' is a [[economy]] or [[economic development]] model based on [[sustainable development]] and a knowledge of [[ecological economics]]. |

A '''green economy''' is a [[economy]] or [[economic development]] model based on [[sustainable development]] and a knowledge of [[ecological economics]]. |

||

| Line 28: | Line 31: | ||

:(3) Locally rooted, based on the belief that an authentic connection to place is the essential pre-condition to sustainability and justice. The Green Economy is a global aggregate of individual communities meeting the needs of its citizens through the responsible, local production and [[Trade|exchange of goods and services]].}} |

:(3) Locally rooted, based on the belief that an authentic connection to place is the essential pre-condition to sustainability and justice. The Green Economy is a global aggregate of individual communities meeting the needs of its citizens through the responsible, local production and [[Trade|exchange of goods and services]].}} |

||

'''The Green Economy Initiative (GEI)''' |

|||

- The UNEP-led '''Green Economy Initiative''', launched in late 2008, consists of several components whose collective overall objective is to provide a macroeconomic analysis of policy reforms and investments in green sectors and in greening brown sectors. The Initiative will assess how sectors – such as renewable energies, clean and efficient technologies, water services and sustainable agriculture – can contribute to [[economic growth]], creation of decent jobs, [[social equity]] and [[poverty reduction]], while addressing [[climate risk]] and other ecological challenges. |

|||

- Within UNEP, the Green Economy Initiative includes three sets of activities: |

|||

1. Producing a '''Green Economy Report''' and related research materials, which will analyse the [[macroeconomic]], [[sustainability]], and [[poverty reduction]] implications of green investment in a range of sectors from [[renewable energy]] to [[sustainable agriculture]] and providing guidance on policies that can catalyse increased investment in these sectors. |

|||

2. Providing advisory services on ways to move towards a green economy in specific countries. |

|||

3. Engaging a wide range of research, non-governmental organizations, businesses and [[UN]] partners in implementing the Green Economy Initiative. |

|||

- Beyond [[UNEP]], the Green Economy Initiative is one of the nine '''UN-wide [[Joint Crisis Initiatives]]''', launched by the UN System’s Chief Executives Board in early 2009. In this context, the Initiative includes a wide range of research activities and capacity-building events from over 20 UN agencies, including the [[Bretton Woods]] Institutions, as well as an Issue Management Group on Green Economy, launched in Washington, DC in March of 2010. |

|||

'''The Green Economy Report (GER)''' |

|||

- '''The Green Economy Report''', to be published in early 2011, uses economic analysis and modelling approaches to demonstrate that greening the economy across a range of sectors can drive economic recovery and growth and lead to future prosperity and job creation, while at the same time addressing social inequalities and environmental challenges. |

|||

- The Report explains the core principles and concepts underlying a green economy and makes the case for the more sustainable use of natural, human and economic capital. The Report also examines the actions governments can take to facilitate the transition to a Green Economy. The scope of these enabling conditions is wider than financial support for investments, and covers the key policy tools and supporting infrastructure that can influence investment and consumption decisions. |

|||

- The Report addresses some of the fundamental questions regarding the reallocation of pools of capital, predominantly from private sources, required to achieve a green economy globally. It explores the extent to which these pools of capital will have to be “greened” in the coming decades to serve the (upfront) capital needs in order to shift the economy into low-carbon and resource efficient sectors. Recognizing the instability of the global financial system, the Report highlights the need for adequate international and local policy and regulatory frameworks and effective measures in order to reduce external costs of portfolio holdings. |

|||

- World-renowned experts and institutions from both developed and developing countries are working with a UNEP team led by [[Pavan Sukhdev]], a former senior banker from [[Deutsche Bank]], to develop the Report. The Report targets decision-makers, seeks to influence business leaders, and explain in simple terms the need for increased environmental investments to promote [[sustainable economic growth]], generate [[employment]], reduce [[poverty]] and increase quality of life. |

|||

- The Green Economy Report will address important sectors of the green economy, together with cross-cutting issues such as finance and other enabling conditions. |

|||

1. [[Agriculture]]: sustainable farming practices will increase productivity in developing countries and create durable jobs along the post-harvest supply chains. |

|||

2. [[Buildings]] are responsible for 40% of primary energy consumption. Retrofitting existing buildings and constructing new “smart” buildings will dramatically reduce energy use and air pollution, while at the same time creating many new jobs. This holds true for both developed and developing countries, and will be especially important as more rural residents migrate to the cities. |

|||

3. [[Cities]] are where more than half the world’s population now lives - and the proportion is set to increase. A green economy, providing efficient transport and energy systems, is vital if urban problems of air pollution, congestion, unsanitary slums and unemployment are to be mitigated. |

|||

4. [[Energy]]: renewable sources of energy, at present only a small portion of the energy spectrum, are a key element in reducing the global reliance on fossil fuels, lessening pollution, providing energy security and helping to meet the MDGs. |

|||

5. [[Fisheries]] is an economic sector currently in crisis, but essential for the provision of protein to a fifth of humanity. Sustainable fishing practices are essential if the world’s fish stocks are to be preserved. Of particular concern is the need to protect coastal fishing communities in developing countries - which can only be achieved with the reform of the fishing industry in the developed world. |

|||

6. [[Forests]] are vital in the fight against climate change, but they remain under threat from unsustainable and illegal logging and from the pressure to gain more land for agriculture. Fortunately, new methods - such as the proposed Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) - are beginning to emerge which reward forest custodians for keeping forests standing to store carbon. This is expected to reduce the incentive to cut down forests for other land-use. |

|||

7. [[Manufacturing]] is responsible for a third of world energy use and generates a quarter of global GHGs. More efficient, less polluting processes, not least in industries such as iron, steel and cement, are needed to meet MDG7 and improve the quality of life that will accompany the other MDGs. |

|||

8. [[Tourism]] (in collaboration with the UN’s World Tourism Organisation), developed in an environmentally sensitive way, will be a great creator of employment, especially in developing countries, and can be an alternative to other, environmentally damaging economic activity. |

|||

9. [[Transport]], whether by land, sea or air, is crucial to economic development, but carries with it the risks of pollution and congestion. Technological innovation will reduce some of the risk, but at least as important will be green policies to maximise the use of clean public transport, both in cities and between cities. Affordable public transport will help achieve MDGs 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 by improving access to employment, schools and health facilities; by being energy efficient, and so less polluting, it will help towards MDG7; as an investment opportunity, it will involve the partnerships envisaged by MDG8. |

|||

10. [[Waste]] traditionally generates considerable economic and social costs, particularly in the health sector. But waste, by definition something not wanted, can to a large extent be redefined as a resource. A green economy will be one that recycles as much waste as is possible, creating value and in the process many sustainable jobs. |

|||

11. [[Water]] is the source of life, but the pressures of population growth and the repercussions of climate change threaten its safe and sustainable supply. Meanwhile, while access to safe drinking water - a target of MDG7 - is now available to 87% of the world’s population, almost half the residents of the world’s developing regions are still without basic sanitation. A green economy would redress the excessive use of water by agriculture and improve urban and rural water networks. It would implement arrangements for payments for ecosystem services (PES) for freshwater, leading to better rewarded wetland and forest stakeholders, including amongst rural communities, and lead to a more secure supply of safe water in developing countries. |

|||

'''Green Economy: Developing Countries Success Stories'''<ref>http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/SuccessStories/tabid/4652/Default.aspx</ref> |

|||

1. '''Renewable Energy in China''': China is taking considerable steps to shift to a low-carbon growth strategy based on the development of renewable energy sources. The outline of 11th Five-year Plan (2006-2010) allocated a significant share of investments to green sectors, with an emphasis on renewable energy and energy efficiency. The Plan projects that the per-unit GDP energy consumption by 2010 should have decreased by 20 per cent compared to 2005. In addition, the Chinese government has committed itself to producing 16 per cent of its primary energy from renewable sources by 2020. |

|||

2. '''Feed-in tariffs in Kenya''': Kenya’s energy profile is characterized by a predominance of traditional biomass energy to meet the energy needs of the rural households and a heavy dependence on imported petroleum for the modern economic sector needs. As a result, the country faces challenges related to unsustainable use of traditional forms of biomass and exposure to high and unstable oil import prices. In March 2008, Kenya’s Ministry of Energy adopted a Feed-in Tariff, based on the realization that “Renewable Energy Sources (RES) including solar, wind, small-hydro, biogas and municipal waste energy have potential for income and employment generation, over and above contributing to the supply and diversification of electricity generation sources”. |

|||

3. '''Organic agriculture in Uganda''': Uganda has taken important steps in transforming conventional agricultural production into an organic farming system, with significant benefits for its economy, society and the environment. Organic Agriculture (OA) is defined by the Codex Alimentarius Commission as a holistic production management system, which promotes and enhances agro-ecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity. It prohibits the use of synthetic inputs, such as drugs, fertilizers and pesticides. Uganda uses among the world’s lowest amount of artificial fertilizers, at less than 2 per cent (or 1kg/ha) of the already very low continent-wide average of 9kg/ha in Sub Saharan Africa. The widespread lack of fertilizer use has been harnessed as a real opportunity to pursue organic forms of agricultural production, a policy direction widely embraced by Uganda. |

|||

4. '''Sustainable urban planning in Brazil''': Rapid growth of urban areas presents both environmental and socio-economic challenges to residents, businesses and municipalities. With inadequate planning and limited finances accommodating the increasing urban populations often results in expansion of informal housing in cities or suburban developments requiring high use of private transport. Brazil has the fourth-largest urban population after China, India, and the US, with an annual urban growth rate of 1.8 per cent between 2005 and 2010. The city of Curitiba, capital of Parana State in Brazil has successfully addressed this challenge by implementing innovative systems over the last decades that have inspired other cities in Brazil, and beyond. Particularly known for its Bus Rapid Transit system, Curitiba also provides an example of integrated urban and industrial planning that enabled the location of new industries and the creation of jobs. |

|||

5. '''Rural ecological infrastructure in India''': India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (NREGA) is a guaranteed wage employment programme that enhances the livelihood security of marginalized households in rural areas. Implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development, NREGA directly touches the lives of the poor, promotes inclusive growth, and also contributes to the restoration and maintenance of ecological infrastructure. In its first two-and-a-half years of operation, from 2006 to 2008, NREGA generated more than 3.5 billion days of work reaching on average 30 million families per year. The programme is implemented in all 615 rural districts of the country, with women representing roughly half the employed workforce. The emphasis is placed on labour-intensive work, prohibiting the use of contractors and machinery. |

|||

6. '''Forest management in Nepal''': Community forestry has contributed to restoring forest resources in Nepal. Forests account for almost 40 per cent of the land in the country. Although this area was decreasing at an annual rate of 1.9 per cent during the 1990s, this decline was reversed, leading to an annual increase of 1.35 per cent over the period 2000 to 2005. Community forestry occupies a central place in forest management in Nepal. In this approach, local users organized as Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) take the lead and manage resources, while the government plays the role of supporter or facilitator. Forest management is a community effort and entails little financial or other involvement on the part of the government. |

|||

7. '''Ecosystem Services in Ecuador''': The city of Quito offers a leading example of the potential for developing markets that channel economic demand for water to upstream areas from which it is supplied. In Quito’s case, the availability of water for the city of about 1.5 million inhabitants and surrounding areas depends on the conservation of protected areas upstream, with 80 per cent of the water supply originating in two ecological reserves, the Cayambe-Coca (400,000 ha) and the Antisana (120,000 ha). The Fund for the Protection of Water – FONAG – was established in 2000 by the municipal government, together with a non-governmental organization, as a trust fund to which water users in Quito contribute. FONAG uses the proceeds to finance critical ecosystem services, including land acquisition for key hydrological functions. |

|||

8. '''Solar energy in Tunisia''': To reduce the country’s dependence on oil and gas, Tunisia’s government has undertaken steps to promote the development and use of renewable energy. A law establishing an “energy conservation system” on energy management in 2005 was immediately followed with the creation of a funding mechanism – the National Fund for Energy Management – to support increased capacity in renewable energy technologies and also improved energy efficiency. The replenishment of this Fund is based on a duty levied on the first registration of private, petrol-powered and diesel powered cars and on import duty or local production duty of air-conditioning equipments with the exclusion of those produced for exports. |

|||

'''Global Green New Deal''' |

|||

In the midst of the global economic crisis, the [[United Nations Environment Programme]] (UNEP) called for a global [[Green New Deal]] according to which governments were encouraged to support its economic transformation to a greener economy.<ref>[http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=548&ArticleID=5955&l=en United Nation Environment Programme (UNEP): "Global green new deal - environmentally-focused investment historic opportunity for 21st century prosperity and job generation." London/Nairobi, October 22, 2008.]</ref> |

In the midst of the global economic crisis, the [[United Nations Environment Programme]] (UNEP) called for a global [[Green New Deal]] according to which governments were encouraged to support its economic transformation to a greener economy.<ref>[http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=548&ArticleID=5955&l=en United Nation Environment Programme (UNEP): "Global green new deal - environmentally-focused investment historic opportunity for 21st century prosperity and job generation." London/Nairobi, October 22, 2008.]</ref> |

||

In response to the financial and economic crisis, [[UNEP]] has called for a “[[Global Green New Deal]]” for reviving the global economy and boosting employment, while simultaneously accelerating the fight against climate change, environmental degradation and poverty. UNEP is recommending that a significant portion of the estimated US$3 trillion in pledged economic stimulus packages be invested in five critical areas: |

|||

- Raising the energy efficiency of old and new buildings; |

|||

- Transitioning to renewable energies including [[wind]], [[solar]], [[geothermal]] and [[biomass]]; |

|||

- Increasing reliance on sustainable transport including [[hybrid vehicles]], [[high speed rail]] and [[bus rapid transit systems]]; |

|||

- Bolstering the planet's ecological infrastructure, including [[freshwaters]], [[forests]], [[soils]] and [[coral reefs]]; |

|||

- Supporting sustainable agriculture, including organic production. |

|||

UNEP’s Global Green New Deal also calls for a range of specific measures aimed at assisting poorer countries in reaching the [[Millennium Development Goals]] ([[MDGs]]) and greening their economies. These include an expansion of [[microcredit]] schemes for clean energy, reform of subsidies from fossil fuels to fisheries, and the greening of overseas development aid. |

|||

A Policy Brief outlining these recommendations was prepared in consultation with over 20 UN agencies and intergovernmental organizations and shared with members of the [[G20]] (“[[London Summit]]”) meeting in April 2009. UNEP followed-up on this initial brief with a Global Green New Deal update that was launched during with the G20 (“[[Pittsburgh Summit]]”) in September 2009. The update summarizes the current amount of green investments included in national financial stimulus packages for a selected group of countries, the rate of green investment disbursement, and progress in domestic policy reforms required to embed these investments in a long-term transition to a green economy. |

|||

The update concludes that much more needs to be done and urges G20 governments to invest US$750 billion of the US$2.5 trillion [[stimulus package]] (about 1 per cent of [[global GDP]]) towards building a green economy – one that reduces carbon dependency, addresses poverty, generates good quality and decent jobs, maintains and restores our natural ecosystems, and moves towards sustainable consumption. |

|||

Green economy includes [[green energy]] generation based on [[renewable energy]] to substitute for [[fossil fuels]] and [[energy conservation]] for [[efficient energy use]]. |

Green economy includes [[green energy]] generation based on [[renewable energy]] to substitute for [[fossil fuels]] and [[energy conservation]] for [[efficient energy use]]. |

||

| Line 70: | Line 143: | ||

*[[Sustainable design]] |

*[[Sustainable design]] |

||

*[[The Clean Tech Revolution]] |

*[[The Clean Tech Revolution]] |

||

*[[The Economics of Ecosystem and Biodiversity]] ([[TEEB]]) |

|||

*[[World energy resources and consumption]] |

*[[World energy resources and consumption]] |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* Kennet M.,and Heinemann V,(2006) Green Economics,Setting the Scene.in International Journal of Green Economics,Vol 1 issue 1/2 (2006) |

* Kennet M.,and Heinemann V,(2006) Green Economics,Setting the Scene.in International Journal of Green Economics,Vol 1 issue 1/2 (2006) |

||

Inderscience.Geneva |

Inderscience.Geneva |

||

*Kennet M., (2009) Emerging Pedogogy in an Emerging Discipline,Green Economics in Reardon J., (2009) Pluralist education, Routledge. |

*Kennet M., (2009) Emerging Pedogogy in an Emerging Discipline,Green Economics in Reardon J., (2009) Pluralist education, Routledge. |

||

* Kennet M., (2008) Introduction to Green Economics, in Harvard School Economics Review. |

* Kennet M., (2008) Introduction to Green Economics, in Harvard School Economics Review. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* King, Andrew; Lenox, Michael, 2002. ‘Does it really pay to be green?’ Journal of Industrial Ecology 5, 105-117. |

* King, Andrew; Lenox, Michael, 2002. ‘Does it really pay to be green?’ Journal of Industrial Ecology 5, 105-117. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* Martinez-Alier, J. (1990) Ecological Economics: Energy, Environment and Society. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell. |

* Martinez-Alier, J. (1990) Ecological Economics: Energy, Environment and Society. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* Røpke, I. (2004) The early history of modern ecological economics. Ecological Economics 50(3-4): 293-314. |

* Røpke, I. (2004) The early history of modern ecological economics. Ecological Economics 50(3-4): 293-314. |

||

* Røpke, I. (2005) Trends in the development of ecological economics from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Ecological Economics 55(2): 262-290. |

* Røpke, I. (2005) Trends in the development of ecological economics from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Ecological Economics 55(2): 262-290. |

||

| Line 87: | Line 163: | ||

* Spash, C. L. (1999) The development of environmental thinking in economics. Environmental Values 8(4): 413-435. |

* Spash, C. L. (1999) The development of environmental thinking in economics. Environmental Values 8(4): 413-435. |

||

* Vatn, A. (2005) Institutions and the Environment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar |

* Vatn, A. (2005) Institutions and the Environment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar |

||

* UNEP (2010), Green Economy Report: A Preview. Available at http://www.unep.org/GreenEconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=JvDFtjopXsA%3d&tabid=1350&language=en-US |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2010), Developing Countries Success Stories. Available at http://www.unep.org/pdf/GreenEconomy_SuccessStories.pdf |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2010), A Brief for Policymakers on the Green Economy and Millennium Development Goals. Available at http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/30/docs/policymakers_brief_GEI&MDG.pdf |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2010), Driving a Green Economy Through Public Finance and Fiscal Policy Reform. Available at http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/30/docs/DrivingGreenEconomy.pdf |

|||

* United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2009), Global Green New Deal Update, Available at http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ciH9RD7XHwc%3d&tabid=1394&language=en-US |

|||

* United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2009), Global Green New Deal, Policy brief, Available at http://www.unep.org/pdf/A_Global_Green_New_Deal_Policy_Brief.pdf |

|||

* United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2008), Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World (Policy messages and main findings for decision makers), http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=hR62Ck7RTX4%3d&tabid=1377&language=en-US |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* Wagner, Ma. (2003) "Does it pay to be eco-efficient in the European energy supply industry?" Zeitschrift für Energiewirtschaft 27(4), 309-318. |

* Wagner, Ma. (2003) "Does it pay to be eco-efficient in the European energy supply industry?" Zeitschrift für Energiewirtschaft 27(4), 309-318. |

||

* Wagner, M. et al. (2002) "The relationship between environmental and economic performance of firms: what does the theory propose and what does the empirical evidence tell us?" Greener Management International 34, 95-108. |

* Wagner, M. et al. (2002) "The relationship between environmental and economic performance of firms: what does the theory propose and what does the empirical evidence tell us?" Greener Management International 34, 95-108. |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* UNEP – The Green Economy Initiative, http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy |

|||

* The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), http://www.teebweb.org |

|||

* The 2012 Earth Summit http://www.earthsummit2012.org/ |

* The 2012 Earth Summit http://www.earthsummit2012.org/ |

||

The Green Economics Institute-http://greeneconomics.org.uk/ |

The Green Economics Institute-http://greeneconomics.org.uk/ |

||

Revision as of 14:23, 13 October 2010

A Green Economy is one that results in improved human will-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. - United Nations Environment Programme (2010)

A green economy is a economy or economic development model based on sustainable development and a knowledge of ecological economics.

Karl Burkart defines a green economy as based on six main sectors:[1]

- Renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal, marine including wave, biogas, and fuel cell)

- Green buildings (green retrofits for energy and water efficiency, residential and commercial assessment; green products and materials, and LEED construction)

- Clean transportation (alternative fuels, public transit, hybrid and electric vehicles, carsharing and carpooling programs)

- Water management (Water reclamation, greywater and rainwater systems, low-water landscaping, water purification, stormwater management)

- Waste management (recycling, municipal solid waste salvage, brownfield land remediation, Superfund cleanup, sustainable packaging)

- Land management (organic agriculture, habitat conservation and restoration; urban forestry and parks, reforestation and afforestation and soil stabilization)

The Global Citizens Center, led by Kevin Danaher, defines green economy in terms of a "triple bottom line," an economy concerned with being:[2]

- (1) Environmentally sustainable, based on the belief that our biosphere is a closed system with finite resources and a limited capacity for self-regulation and self-renewal. We depend on the earth’s natural resources, and therefore we must create an economic system that respects the integrity of ecosystems and ensures the resilience of life supporting systems.

- (2) Socially just, based on the belief that culture and human dignity are precious resources that, like our natural resources, require responsible stewardship to avoid their depletion. We must create a vibrant economic system that ensures all people have access to a decent standard of living and full opportunities for personal and social development.

- (3) Locally rooted, based on the belief that an authentic connection to place is the essential pre-condition to sustainability and justice. The Green Economy is a global aggregate of individual communities meeting the needs of its citizens through the responsible, local production and exchange of goods and services.

The Green Economy Initiative (GEI)

- The UNEP-led Green Economy Initiative, launched in late 2008, consists of several components whose collective overall objective is to provide a macroeconomic analysis of policy reforms and investments in green sectors and in greening brown sectors. The Initiative will assess how sectors – such as renewable energies, clean and efficient technologies, water services and sustainable agriculture – can contribute to economic growth, creation of decent jobs, social equity and poverty reduction, while addressing climate risk and other ecological challenges.

- Within UNEP, the Green Economy Initiative includes three sets of activities:

1. Producing a Green Economy Report and related research materials, which will analyse the macroeconomic, sustainability, and poverty reduction implications of green investment in a range of sectors from renewable energy to sustainable agriculture and providing guidance on policies that can catalyse increased investment in these sectors.

2. Providing advisory services on ways to move towards a green economy in specific countries.

3. Engaging a wide range of research, non-governmental organizations, businesses and UN partners in implementing the Green Economy Initiative.

- Beyond UNEP, the Green Economy Initiative is one of the nine UN-wide Joint Crisis Initiatives, launched by the UN System’s Chief Executives Board in early 2009. In this context, the Initiative includes a wide range of research activities and capacity-building events from over 20 UN agencies, including the Bretton Woods Institutions, as well as an Issue Management Group on Green Economy, launched in Washington, DC in March of 2010.

The Green Economy Report (GER)

- The Green Economy Report, to be published in early 2011, uses economic analysis and modelling approaches to demonstrate that greening the economy across a range of sectors can drive economic recovery and growth and lead to future prosperity and job creation, while at the same time addressing social inequalities and environmental challenges.

- The Report explains the core principles and concepts underlying a green economy and makes the case for the more sustainable use of natural, human and economic capital. The Report also examines the actions governments can take to facilitate the transition to a Green Economy. The scope of these enabling conditions is wider than financial support for investments, and covers the key policy tools and supporting infrastructure that can influence investment and consumption decisions.

- The Report addresses some of the fundamental questions regarding the reallocation of pools of capital, predominantly from private sources, required to achieve a green economy globally. It explores the extent to which these pools of capital will have to be “greened” in the coming decades to serve the (upfront) capital needs in order to shift the economy into low-carbon and resource efficient sectors. Recognizing the instability of the global financial system, the Report highlights the need for adequate international and local policy and regulatory frameworks and effective measures in order to reduce external costs of portfolio holdings.

- World-renowned experts and institutions from both developed and developing countries are working with a UNEP team led by Pavan Sukhdev, a former senior banker from Deutsche Bank, to develop the Report. The Report targets decision-makers, seeks to influence business leaders, and explain in simple terms the need for increased environmental investments to promote sustainable economic growth, generate employment, reduce poverty and increase quality of life.

- The Green Economy Report will address important sectors of the green economy, together with cross-cutting issues such as finance and other enabling conditions.

1. Agriculture: sustainable farming practices will increase productivity in developing countries and create durable jobs along the post-harvest supply chains. 2. Buildings are responsible for 40% of primary energy consumption. Retrofitting existing buildings and constructing new “smart” buildings will dramatically reduce energy use and air pollution, while at the same time creating many new jobs. This holds true for both developed and developing countries, and will be especially important as more rural residents migrate to the cities. 3. Cities are where more than half the world’s population now lives - and the proportion is set to increase. A green economy, providing efficient transport and energy systems, is vital if urban problems of air pollution, congestion, unsanitary slums and unemployment are to be mitigated. 4. Energy: renewable sources of energy, at present only a small portion of the energy spectrum, are a key element in reducing the global reliance on fossil fuels, lessening pollution, providing energy security and helping to meet the MDGs. 5. Fisheries is an economic sector currently in crisis, but essential for the provision of protein to a fifth of humanity. Sustainable fishing practices are essential if the world’s fish stocks are to be preserved. Of particular concern is the need to protect coastal fishing communities in developing countries - which can only be achieved with the reform of the fishing industry in the developed world. 6. Forests are vital in the fight against climate change, but they remain under threat from unsustainable and illegal logging and from the pressure to gain more land for agriculture. Fortunately, new methods - such as the proposed Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) - are beginning to emerge which reward forest custodians for keeping forests standing to store carbon. This is expected to reduce the incentive to cut down forests for other land-use. 7. Manufacturing is responsible for a third of world energy use and generates a quarter of global GHGs. More efficient, less polluting processes, not least in industries such as iron, steel and cement, are needed to meet MDG7 and improve the quality of life that will accompany the other MDGs. 8. Tourism (in collaboration with the UN’s World Tourism Organisation), developed in an environmentally sensitive way, will be a great creator of employment, especially in developing countries, and can be an alternative to other, environmentally damaging economic activity. 9. Transport, whether by land, sea or air, is crucial to economic development, but carries with it the risks of pollution and congestion. Technological innovation will reduce some of the risk, but at least as important will be green policies to maximise the use of clean public transport, both in cities and between cities. Affordable public transport will help achieve MDGs 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 by improving access to employment, schools and health facilities; by being energy efficient, and so less polluting, it will help towards MDG7; as an investment opportunity, it will involve the partnerships envisaged by MDG8. 10. Waste traditionally generates considerable economic and social costs, particularly in the health sector. But waste, by definition something not wanted, can to a large extent be redefined as a resource. A green economy will be one that recycles as much waste as is possible, creating value and in the process many sustainable jobs. 11. Water is the source of life, but the pressures of population growth and the repercussions of climate change threaten its safe and sustainable supply. Meanwhile, while access to safe drinking water - a target of MDG7 - is now available to 87% of the world’s population, almost half the residents of the world’s developing regions are still without basic sanitation. A green economy would redress the excessive use of water by agriculture and improve urban and rural water networks. It would implement arrangements for payments for ecosystem services (PES) for freshwater, leading to better rewarded wetland and forest stakeholders, including amongst rural communities, and lead to a more secure supply of safe water in developing countries.

Green Economy: Developing Countries Success Stories[3]

1. Renewable Energy in China: China is taking considerable steps to shift to a low-carbon growth strategy based on the development of renewable energy sources. The outline of 11th Five-year Plan (2006-2010) allocated a significant share of investments to green sectors, with an emphasis on renewable energy and energy efficiency. The Plan projects that the per-unit GDP energy consumption by 2010 should have decreased by 20 per cent compared to 2005. In addition, the Chinese government has committed itself to producing 16 per cent of its primary energy from renewable sources by 2020.

2. Feed-in tariffs in Kenya: Kenya’s energy profile is characterized by a predominance of traditional biomass energy to meet the energy needs of the rural households and a heavy dependence on imported petroleum for the modern economic sector needs. As a result, the country faces challenges related to unsustainable use of traditional forms of biomass and exposure to high and unstable oil import prices. In March 2008, Kenya’s Ministry of Energy adopted a Feed-in Tariff, based on the realization that “Renewable Energy Sources (RES) including solar, wind, small-hydro, biogas and municipal waste energy have potential for income and employment generation, over and above contributing to the supply and diversification of electricity generation sources”.

3. Organic agriculture in Uganda: Uganda has taken important steps in transforming conventional agricultural production into an organic farming system, with significant benefits for its economy, society and the environment. Organic Agriculture (OA) is defined by the Codex Alimentarius Commission as a holistic production management system, which promotes and enhances agro-ecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity. It prohibits the use of synthetic inputs, such as drugs, fertilizers and pesticides. Uganda uses among the world’s lowest amount of artificial fertilizers, at less than 2 per cent (or 1kg/ha) of the already very low continent-wide average of 9kg/ha in Sub Saharan Africa. The widespread lack of fertilizer use has been harnessed as a real opportunity to pursue organic forms of agricultural production, a policy direction widely embraced by Uganda.

4. Sustainable urban planning in Brazil: Rapid growth of urban areas presents both environmental and socio-economic challenges to residents, businesses and municipalities. With inadequate planning and limited finances accommodating the increasing urban populations often results in expansion of informal housing in cities or suburban developments requiring high use of private transport. Brazil has the fourth-largest urban population after China, India, and the US, with an annual urban growth rate of 1.8 per cent between 2005 and 2010. The city of Curitiba, capital of Parana State in Brazil has successfully addressed this challenge by implementing innovative systems over the last decades that have inspired other cities in Brazil, and beyond. Particularly known for its Bus Rapid Transit system, Curitiba also provides an example of integrated urban and industrial planning that enabled the location of new industries and the creation of jobs.

5. Rural ecological infrastructure in India: India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (NREGA) is a guaranteed wage employment programme that enhances the livelihood security of marginalized households in rural areas. Implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development, NREGA directly touches the lives of the poor, promotes inclusive growth, and also contributes to the restoration and maintenance of ecological infrastructure. In its first two-and-a-half years of operation, from 2006 to 2008, NREGA generated more than 3.5 billion days of work reaching on average 30 million families per year. The programme is implemented in all 615 rural districts of the country, with women representing roughly half the employed workforce. The emphasis is placed on labour-intensive work, prohibiting the use of contractors and machinery.

6. Forest management in Nepal: Community forestry has contributed to restoring forest resources in Nepal. Forests account for almost 40 per cent of the land in the country. Although this area was decreasing at an annual rate of 1.9 per cent during the 1990s, this decline was reversed, leading to an annual increase of 1.35 per cent over the period 2000 to 2005. Community forestry occupies a central place in forest management in Nepal. In this approach, local users organized as Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) take the lead and manage resources, while the government plays the role of supporter or facilitator. Forest management is a community effort and entails little financial or other involvement on the part of the government.

7. Ecosystem Services in Ecuador: The city of Quito offers a leading example of the potential for developing markets that channel economic demand for water to upstream areas from which it is supplied. In Quito’s case, the availability of water for the city of about 1.5 million inhabitants and surrounding areas depends on the conservation of protected areas upstream, with 80 per cent of the water supply originating in two ecological reserves, the Cayambe-Coca (400,000 ha) and the Antisana (120,000 ha). The Fund for the Protection of Water – FONAG – was established in 2000 by the municipal government, together with a non-governmental organization, as a trust fund to which water users in Quito contribute. FONAG uses the proceeds to finance critical ecosystem services, including land acquisition for key hydrological functions.

8. Solar energy in Tunisia: To reduce the country’s dependence on oil and gas, Tunisia’s government has undertaken steps to promote the development and use of renewable energy. A law establishing an “energy conservation system” on energy management in 2005 was immediately followed with the creation of a funding mechanism – the National Fund for Energy Management – to support increased capacity in renewable energy technologies and also improved energy efficiency. The replenishment of this Fund is based on a duty levied on the first registration of private, petrol-powered and diesel powered cars and on import duty or local production duty of air-conditioning equipments with the exclusion of those produced for exports.

Global Green New Deal In the midst of the global economic crisis, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) called for a global Green New Deal according to which governments were encouraged to support its economic transformation to a greener economy.[4]

In response to the financial and economic crisis, UNEP has called for a “Global Green New Deal” for reviving the global economy and boosting employment, while simultaneously accelerating the fight against climate change, environmental degradation and poverty. UNEP is recommending that a significant portion of the estimated US$3 trillion in pledged economic stimulus packages be invested in five critical areas: - Raising the energy efficiency of old and new buildings; - Transitioning to renewable energies including wind, solar, geothermal and biomass; - Increasing reliance on sustainable transport including hybrid vehicles, high speed rail and bus rapid transit systems; - Bolstering the planet's ecological infrastructure, including freshwaters, forests, soils and coral reefs; - Supporting sustainable agriculture, including organic production.

UNEP’s Global Green New Deal also calls for a range of specific measures aimed at assisting poorer countries in reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and greening their economies. These include an expansion of microcredit schemes for clean energy, reform of subsidies from fossil fuels to fisheries, and the greening of overseas development aid.

A Policy Brief outlining these recommendations was prepared in consultation with over 20 UN agencies and intergovernmental organizations and shared with members of the G20 (“London Summit”) meeting in April 2009. UNEP followed-up on this initial brief with a Global Green New Deal update that was launched during with the G20 (“Pittsburgh Summit”) in September 2009. The update summarizes the current amount of green investments included in national financial stimulus packages for a selected group of countries, the rate of green investment disbursement, and progress in domestic policy reforms required to embed these investments in a long-term transition to a green economy.

The update concludes that much more needs to be done and urges G20 governments to invest US$750 billion of the US$2.5 trillion stimulus package (about 1 per cent of global GDP) towards building a green economy – one that reduces carbon dependency, addresses poverty, generates good quality and decent jobs, maintains and restores our natural ecosystems, and moves towards sustainable consumption.

Green economy includes green energy generation based on renewable energy to substitute for fossil fuels and energy conservation for efficient energy use. The green economy is considered being able to both create green jobs, ensure real, sustainable economic growth, and prevent environmental pollution, global warming, resource depletion, and environmental degradation.

Because the market failure related to environmental and climate protection as a result of external costs, high future commercial rates and associated high initial costs for research, development, and marketing of green energy sources and green products prevents firms from being voluntarily interested in reducing environment-unfriendly activities (Reinhardt, 1999; King and Lenox, 2002; Wagner, 203; Wagner, et al., 2005), the green economy is considered needing government subsidies as market incentives to motivate firms to invest and produce green products and services. The German Renewable Energy Act, legislations of many other EU countries and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, all provide such market incentives.

However, there are still incompatibilities between the UN global green new deal call and the existing international trade mechanism in terms of market incentives. For example, the WTO Subsidies Agreement has strict rules against government subsidies, especially for exported goods. Such incompatibilities may serve as obstacles to governments' responses to the UN Global green new deal call. WTO needs to update its subsidy rules to account for the needs of accelerating the transition to the green, low-carbon economy. Research is urgently needed to inform the governments and the international community how the governments should promote the green economy within their national borders without being engaged in trade wars in the name of the green economy and how they should cooperate in their promotional efforts at a coordinated international level.

Notes

- ^ http://www.mnn.com/green-tech/research-innovations/blogs/how-do-you-define-the-green-economy

- ^ http://www.globalcitizencenter.org/content/view/2/1/

- ^ http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/SuccessStories/tabid/4652/Default.aspx

- ^ United Nation Environment Programme (UNEP): "Global green new deal - environmentally-focused investment historic opportunity for 21st century prosperity and job generation." London/Nairobi, October 22, 2008.

See also

- Agroecology

- Alternative energy indexes

- Ecology of contexts

- Embodied energy

- Embodied water

- Energy accounting

- Energy conservation

- Energy economics

- Energy policy

- Energy quality

- Environmental economics

- Environmental ethics

- Exergy

- Feed-in tariff

- Global warming

- Green accounting

- Human development theory

- Human ecology

- ISO 14000

- Industrial ecology

- List of Green topics

- Natural capital

- Natural resource economics

- Passive solar building design

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Renewable heat

- Sustainable design

- The Clean Tech Revolution

- The Economics of Ecosystem and Biodiversity (TEEB)

- World energy resources and consumption

References

- Common, M. and Stagl, S. 2005. Ecological Economics: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Daly, H. and Townsend, K. (eds.) 1993. Valuing The Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics. Cambridge, Mass.; London, England: MIT Press.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1975. Energy and economic myths. Southern Economic Journal 41: 347-381.

- Kennet M.,and Heinemann V,(2006) Green Economics,Setting the Scene.in International Journal of Green Economics,Vol 1 issue 1/2 (2006)

Inderscience.Geneva *Kennet M., (2009) Emerging Pedogogy in an Emerging Discipline,Green Economics in Reardon J., (2009) Pluralist education, Routledge.

- Kennet M., (2008) Introduction to Green Economics, in Harvard School Economics Review.

- King, Andrew; Lenox, Michael, 2002. ‘Does it really pay to be green?’ Journal of Industrial Ecology 5, 105-117.

- Krishnan R, Harris JM, Goodwin NR. (1995). A Survey of Ecological Economics. Island Press. ISBN 1559634111, 9781559634113.

- Martinez-Alier, J. (1990) Ecological Economics: Energy, Environment and Society. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell.

- Martinez-Alier, J., Ropke, I. eds.(2008), Recent Developments in Ecological Economics, 2 vols., E. Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

- Røpke, I. (2004) The early history of modern ecological economics. Ecological Economics 50(3-4): 293-314.

- Røpke, I. (2005) Trends in the development of ecological economics from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Ecological Economics 55(2): 262-290.

- Reinhardt, F. (1999) ‘Market failure and the environmental policies of firms: economic rationales for ‘beyond compliance’ behavior.’ Journal of Industrial Ecology 3(1), 9-21.

- Spash, C. L. (1999) The development of environmental thinking in economics. Environmental Values 8(4): 413-435.

- Vatn, A. (2005) Institutions and the Environment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

- UNEP (2010), Green Economy Report: A Preview. Available at http://www.unep.org/GreenEconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=JvDFtjopXsA%3d&tabid=1350&language=en-US

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2010), Developing Countries Success Stories. Available at http://www.unep.org/pdf/GreenEconomy_SuccessStories.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2010), A Brief for Policymakers on the Green Economy and Millennium Development Goals. Available at http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/30/docs/policymakers_brief_GEI&MDG.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2010), Driving a Green Economy Through Public Finance and Fiscal Policy Reform. Available at http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/30/docs/DrivingGreenEconomy.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2009), Global Green New Deal Update, Available at http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ciH9RD7XHwc%3d&tabid=1394&language=en-US

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2009), Global Green New Deal, Policy brief, Available at http://www.unep.org/pdf/A_Global_Green_New_Deal_Policy_Brief.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2008), Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World (Policy messages and main findings for decision makers), http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=hR62Ck7RTX4%3d&tabid=1377&language=en-US

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2008), ‘Global green new deal - environmentally-focused investment historic opportunity for 21st century prosperity and job generation.’ London/Nairobi, October 22.

- Wagner, Ma. (2003) "Does it pay to be eco-efficient in the European energy supply industry?" Zeitschrift für Energiewirtschaft 27(4), 309-318.

- Wagner, M. et al. (2002) "The relationship between environmental and economic performance of firms: what does the theory propose and what does the empirical evidence tell us?" Greener Management International 34, 95-108.

External links

- UNEP – The Green Economy Initiative, http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy

- The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), http://www.teebweb.org

- The 2012 Earth Summit http://www.earthsummit2012.org/

The Green Economics Institute-http://greeneconomics.org.uk/

- The International Society for Ecological Economics (ISEE) - http://www.ecoeco.org/

- Green Recovery - http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2008/09/green_recovery.html

- The International Journal of Green Economics, http://www.inderscience.com/ijge

- Eco-Economy Indicators: http://www.earth-policy.org/Indicators/index.htm

- EarthTrends World Resources Institute - http://earthtrends.wri.org/index.php

- The Inspired Economist.

- Ecological Economics Encyclopedia - http://www.ecoeco.org/education_encyclopedia.php

- The academic journal, Ecological Economics - http://www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

- The US Society of Ecological Economics - http://www.ussee.org/

- The Beijer International Institute for Ecological Economics - http://www.beijer.kva.se/

- Green Economist website: http://www.greeneconomist.org/

- Sustainable Prosperity - http://sustainableprosperity.ca/

- World Resources Forum - http://www.worldresourcesforum.org

- The Gund Institute of Ecological Economics - http://www.uvm.edu/giee

- Ecological Economics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute - http://www.economics.rpi.edu/ecological.html

- An ecological economics article about reconciling economics and its supporting ecosystem - http://www.fs.fed.us/eco/s21pre.htm

- "Economics in a Full World", by Herman E. Daly - http://sef.umd.edu/files/ScientificAmerican_Daly_05.pdf

- Steve Charnovitz, "Living in an Ecolonomy: Environmental Cooperation and the GATT," Kennedy School of Government, April 1994.

- NOAA Economics of Ecosystems Data & Products – http://www.economics.noaa.gov/?goal=ecosystems