United States federal budget: Difference between revisions

→External links: Added a link to Research!America's Understanding the Federal Budget page |

|||

| Line 465: | Line 465: | ||

*{{NYTtopic|subjects/f/federal_budget_us|Federal Budget (US)}} |

*{{NYTtopic|subjects/f/federal_budget_us|Federal Budget (US)}} |

||

*[http://pgpf.org/Issues/Fiscal-Outlook/2011/01/20/~/media/88A2881EBE18412EB569ECFC626DA220 Peter G. Peterson Institute-2011 Fiscal Solutions Initiative-Report] |

*[http://pgpf.org/Issues/Fiscal-Outlook/2011/01/20/~/media/88A2881EBE18412EB569ECFC626DA220 Peter G. Peterson Institute-2011 Fiscal Solutions Initiative-Report] |

||

*[http://www.researchamerica.org/understanding_federal_budget] |

|||

{{United States topics}} |

{{United States topics}} |

||

Revision as of 18:40, 19 July 2011

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Budget and debt in the United States of America |

|---|

|

The Budget of the United States Government is the President's proposal to the U.S. Congress which recommends funding levels for the next fiscal year, beginning October 1. Congressional decisions are governed by rules and legislation regarding the federal budget process. Budget committees set spending limits for the House and Senate committees and for Appropriations subcommittees, which then approve individual appropriations bills to allocate funding to various federal programs.

After Congress approves an appropriations bill, it is sent to the President, who may sign it into law, or may veto it. A vetoed bill is sent back to Congress, which can pass it into law with a two-thirds majority in each chamber. Congress may also combine all or some appropriations bills into an omnibus reconciliation bill. In addition, the president may request and the Congress may pass supplemental appropriations bills or emergency supplemental appropriations bills.

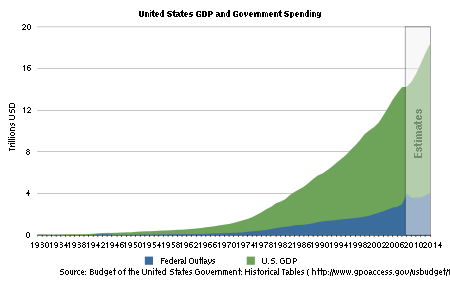

Several government agencies provide budget data and analysis. These include the Government Accountability Office (GAO), Congressional Budget Office, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the U.S. Treasury Department. These agencies have reported that the federal government is facing a series of important financing challenges. In the short-run, tax revenues have declined significantly due to a severe recession and tax policy choices, while expenditures have expanded for wars, unemployment insurance and other safety net spending.[1][2] In the long-run, expenditures related to healthcare programs such as Medicare and Medicaid are growing considerably faster than the economy overall as the population matures.[3][4]

Budget principles

The U.S. Constitution (Article I, section 9, clause 7) states that "[n]o money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time."

Each year, the President of the United States submits his budget request to Congress for the following fiscal year as required by the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921. Current law (31 U.S.C. § 1105(a)) requires the president to submit a budget no earlier than the first Monday in January, and no later than the first Monday in February. Typically, presidents submit budgets on the first Monday in February. The budget submission has been delayed, however, in some new presidents' first year when previous president belonged to a different party.

The federal budget is calculated largely on a cash basis. That is, revenues and outlays are recognized when transactions are made. Therefore, the full long-term costs of entitlement programs such as Medicare, Social Security, and the federal portion of Medicaid are not reflected in the federal budget. By contrast, many businesses and some foreign governments have adopted forms of accrual accounting, which recognizes obligations and revenues when they are incurred. The costs of some federal credit and loan programs, according to provisions of the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990, are calculated on a net present value basis.[5]

Federal agencies cannot spend money unless funds are authorized and appropriated. Typically, separate Congressional committees have jurisdiction over authorization and appropriations. The House and Senate Appropriations Committees currently have 12 subcommittees, which are responsible for drafting the 12 regular appropriations bills that determine amounts of discretionary spending for various federal programs. Appropriations bills must pass both the House and Senate and then be signed by the president in order to give federal agencies legal authority to spend.[6] In many recent years, regular appropriations bills have been combined into "omnibus" bills.

Congress may also pass "special" or "emergency" appropriations. Spending that is deemed an "emergency" is exempt from certain Congressional budget enforcement rules. Funds for disaster relief have sometimes come from supplemental appropriations, such as after Hurricane Katrina. In other cases, funds included in emergency supplemental appropriations bills support activities not obviously related to actual emergencies, such as parts of the 2000 Census of Population and Housing. Special appropriations have been used to fund most of the costs of war and occupation in Iraq and Afghanistan so far.

Budget resolutions and appropriations bills, which reflect spending priorities of Congress, will usually differ from funding levels in the president's budget. The president, however, retains substantial influence over the budget process through his veto power and through his congressional allies when his party has a majority in Congress.

Federal budget data

Several government agencies provide budget data. These include the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the Congressional Budget Office, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the U.S. Treasury Department. CBO publishes The Budget and Economic Outlook in January, which is typically updated in August. It also publishes a Monthly Budget Review. OMB, which is responsible for organizing the President's budget presented in February, typically issues a budget update in July. GAO and Treasury issue Financial Statements of the U.S. Government, usually in the December following the close of the federal fiscal year, which occurs September 30. There is a corresponding Citizen's Guide, a short summary. The Treasury Department also produces a Combined Statement of Receipts, Outlays, and Balances each December for the preceding fiscal year, which provides detailed data on federal financial activities.

Historical tables within the President's Budget (OMB) provides a wide range of data on Federal Government finances. Many of the data series begin in 1940 and include estimates of the President’s Budget for 2009–2014. Additionally, Table 1.1 provides data on receipts, outlays, and surpluses or deficits for 1901–1939 and for earlier multi-year periods. This document is composed of 17 sections, each of which has one or more tables. Each section covers a common theme. Section 1, for example, provides an overview of the budget and off-budget totals; Section 2 provides tables on receipts by source; and Section 3 shows outlays by function. When a section contains several tables, the general rule is to start with tables showing the broadest overview data and then work down to more detailed tables. The purpose of these tables is to present a broad range of historical budgetary data in one convenient reference source and to provide relevant comparisons likely to be most useful. The most common comparisons are in terms of proportions (e.g., each major receipt category as a percentage of total receipts and of the gross domestic product).[7]

Federal budget projections

CBO calculates 35-year baseline projections, which are used extensively in the budget process. Baseline projections are intended to reflect spending under current law, and are not intended as predictions of the most likely path of the economy. During the George W. Bush Administration, OMB presented 5-year projections, but presented 45-year projections in the FY2010 budget submission. CBO and GAO issue long-term projections from time to time.

Major receipt categories

During FY 2010, the federal government collected approximately $2.16 trillion in tax revenue. Primary receipt categories included individual income taxes (42%), Social Security/Social Insurance taxes (40%), and corporate taxes (9%).[8] Other types included excise, estate and gift taxes.

Tax revenues have averaged approximately 18.3% of gross domestic product (GDP) over the 1970-2009 period, generally ranging plus or minus 2% from that level. Tax revenues are significantly affected by the economy. Recessions typically reduce government tax collections as economic activity slows. For example, tax revenues declined from $2.5 trillion in 2008 to $2.1 trillion in 2009, and remained at that level in 2010. During 2009, individual income taxes declined 20%, while corporate taxes declined 50%. At 14.9% of GDP, the 2009 and 2010 collections were the lowest level of the past 50 years.[8][9]

Tax policy

Tax descriptions

The federal personal income tax is progressive, meaning a higher marginal tax rate is applied to higher ranges of income. For example, in 2010 the tax rate that applied to the first $17,000 in gross income for a couple filing jointly was 10%, while the rate applied to income over $379,150 was 35%. The top marginal tax rate has declined considerably since 1980. For example, the top tax rate was lowered from 70% to 50% in 1980 and reached as low as 28% in 1988. The most recent changes were the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003, extended by President Obama in 2010, which lowered the top rate from 39.6% to 35%.[10] There are numerous exemptions and deductions, that typically result in a range of 35-40% of U.S. households owing no federal income tax. The recession and tax cut stimulus measures increased this to 51% for 2009, versus 38% in 2007.[11]

The federal payroll tax (FICA) is a flat tax used to fund Social Security and Medicare. For the Social Security portion, employers and employees each pay 6.2% of the workers gross pay, a total of 12.4%. The Social Security portion is capped at $106,800, meaning income above this amount is not subject to the tax. The Medicare portion is also paid by employer and employee each at 1.45% and is not capped.[12] The payroll tax is considered by some to be a form of social insurance rather than a tax, due to the benefits these programs pay to qualified recipients. For calendar year 2011, the employee's portion of the payroll tax was reduced to 4.2% as an economic stimulus measure.[13]

Tax expenditures

The term "tax expenditures" refers to income exemptions or deductions that reduce the tax collections that would be made applying a particular tax rate alone. In November 2009, The Economist estimated the additional federal tax revenue generated from eliminating certain tax expenditures, for the 2013-2014 period. These included: income exemptions for employer-provided health insurance ($215 billion); and various income deductions such as mortgage interest ($147B), state & local taxes ($65B), capital gains on homes ($60B), property taxes ($33B) and municipal bond interest ($37B). These total $557 billion. All of these steps together would reduce the projected deficit at that time by nearly half.[14]

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in 2008 the amount of federal tax expenditures for the five year (2008-2012) period. Examples include: Exclusions for healthcare insurance paid for by employers-$680B; reduced tax rate on dividends and long-term capital gains-$668B; deduction for mortgage interest on owner-occupied residences-$444B; exclusions for pre-tax defined benefit or defined contribution pension contributions such as to 401K plans-$554B; deductions for non-business state and local income taxes-$242B; deductions for charitable contributions-$205B; exclusion of benefits under healthcare insurance "cafeteria" plans-$201B; exclusion for interest on state and local government bonds-$147B; exclusion for Medicare benefits-$134B; deduction for real property taxes-$112B; dependent credit for children under 17 years of age-$105B; exclusion for capital gains on sale of primary residence-$90B; and deductions for long-term care and other medical expenses-$68B.[15]

According to the Center for American Progress, annual tax expenditures have increased from $526 billion in 1982 to $1,025 billion in 2010, adjusted for inflation (measured in 2010 dollars).[16] Economist Mark Zandi wrote in July 2011 that tax expenditures should be considered a form of government spending.[17]

U.S. taxes relative to foreign countries

Comparison of tax rates around the world is difficult and somewhat subjective. Tax laws in most countries are extremely complex, and tax burden falls differently on different groups in each country and sub-national units (states, counties and municipalities) and the types of services rendered through those taxes are also different.

One way to measure the overall tax burden is by looking at it as a percentage of the overall economy in terms of GDP. The Tax Policy Center wrote: "U.S. taxes are low relative to those in other developed countries. In 2006 U.S. taxes at all levels of government claimed 28 percent of GDP, compared with an average of 36 percent of GDP for the 30 member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)."[18] Economist Simon Johnson wrote in 2010: "The U.S. government doesn’t take in much tax revenue -- at least 10 percentage points of GDP less than comparable developed economies -- and it also doesn’t spend much except on the military, Social Security and Medicare."[19] A comparison of taxation on individuals amongst OECD countries shows that the U.S. tax burden is just slightly below the average tax for middle income earners.[20]

In comparing corporate taxes, the Congressional Budget Office found in 2005 that the top statutory tax rate was the third highest among OECD countries behind Japan and Germany. However, the U.S. ranked 27th lowest of 30 OECD countries in its collection of corporate taxes relative to GDP, at 1.8% vs. the average 2.5%.[21] Bruce Bartlett wrote in May 2011: "...one almost never hears that total revenues are at their lowest level in two or three generations as a share of G.D.P. or that corporate tax revenues as a share of G.D.P. are the lowest among all major countries. One hears only that the statutory corporate tax rate in the United States is high compared with other countries, which is true but not necessarily relevant. The economic importance of statutory tax rates is blown far out of proportion by Republicans looking for ways to make taxes look high when they are quite low."[22]

Major expenditure categories

The federal government's expenditures in FY2010 included Medicare & Medicaid ($793B or 23%), Social Security ($701B or 20%), Defense Department ($689B or 20%), non-defense discretionary ($660B or 19%), other ($416B or 12%) and interest ($197B or 6%). Expenditures are classified as mandatory, with payments required by specific laws, or discretionary, with payment amounts renewed annually as part of the budget process. During FY 2010, the federal government spent $3.46 trillion on a budget or cash basis, down 2% vs. FY 2009 but up 16% versus FY2008 spend of $2.97 trillion. Expenditures averaged 20.6% GDP from 1971 to 2008, generally ranging +/-2% GDP from that level. In 2009 and 2010, expenditures averaged 24.4% GDP.[23]

Mandatory spending and entitlements

Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid expenditures are funded by permanent appropriations and so are considered mandatory spending. Social Security and Medicare are sometimes called "entitlements," because people meeting relevant eligibility requirements are legally entitled to benefits, although most pay taxes into these programs throughout their working lives. Some programs, such as Food Stamps, are appropriated entitlements. Some mandatory spending, such as Congressional salaries, is not part of any entitlement program. Mandatory spending accounted for 53% of total federal outlays in FY2008, with net interest payments accounting for an additional 8.5%.[24]

Mandatory spending is expected to increase as a share of GDP. This is due in part to demographic trends, as the number of workers continues declining relative to those receiving benefits. For example, the number of workers per retiree was 5.1 in 1960; this declined to 3.0 in 2010 and is projected to decline to 2.2 by 2030.[25][26] These programs are also affected by per-person costs, which are also expected to increase at a rate significantly higher than the economy. This unfavorable combination of demographics and per-capita rate increases is expected to drive both Social Security and Medicare into large deficits during the 21st century. Unless these long-term fiscal imbalances are addressed by reforms to these programs, raising taxes or drastic cuts in discretionary programs, the federal government will at some point be unable to pay its obligations without significant risk to the value of the dollar (inflation).[27][28]

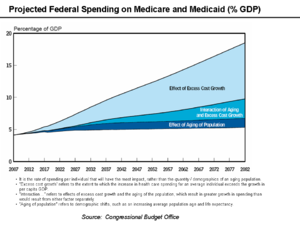

- Medicare was established in 1965 and expanded thereafter. In 2009, the program covered an estimated 45 million persons (38 million aged and 7 million disabled). It consists of four distinct parts which are funded differently: Hospital Insurance, mainly funded by a dedicated payroll tax of 2.9% of earnings, shared equally between employers and workers; Supplementary Medical Insurance, funded through beneficiary premiums (set at 25% of estimated program costs for the aged) and general revenues (the remaining amount, approximately 75%); Medicare Advantage, a private plan option for beneficiaries, funded through the Hospital Insurance and Supplementary Medical Insurance trust funds; and the "Part D" prescription drug benefits, for which funding is included in the Supplementary Medical Insurance trust fund and is financed through beneficiary premiums (about 25%) and general revenues (about 75%).[29] Spending on Medicare and Medicaid is projected to grow dramatically in coming decades. The number of persons enrolled in Medicare is expected to increase from 47 million in 2010 to 80 million by 2030.[30] While the same demographic trends that affect Social Security also affect Medicare, rapidly rising medical prices appear to be a more important cause of projected spending increases. CBO expects Medicare and Medicaid to continue growing, rising from 5.3% GDP in 2009 to 10.0% in 2035 and 19.0% by 2082. CBO has indicated healthcare spending per beneficiary is the primary long-term fiscal challenge.[31] Various reform strategies were proposed for healthcare,[32] and in March 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was enacted as a means of health care reform.

- Social Security is a social insurance program officially called "Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance" (OASDI), in reference to its three components. It is primarily funded through a dedicated payroll tax of 12.4%. During 2009, total benefits of $686 billion were paid out versus income (taxes and interest) of $807 billion, a $121 billion annual surplus. An estimated 156 million people paid into the program and 53 million received benefits, roughly 2.94 workers per beneficiary.[33] Since the Greenspan Commission in the early 1980s, Social Security has cumulatively collected far more in payroll taxes dedicated to the program than it has paid out to recipients—nearly $2.4 trillion by 2008. This annual surplus is credited to Social Security trust funds that hold special non-marketable Treasury securities, and this surplus amount is commonly referred to as the "Social Security Trust Fund". The proceeds are paid into the U.S. Treasury where they may be used for other government purposes. Social Security spending will increase sharply over the next decades, largely due to the retirement of the baby boom generation. The number of program recipients is expected to increase from 44 million in 2010 to 73 million in 2030.[30] Program spending is projected to rise from 4.8% of GDP in 2010 to 5.9% of GDP by 2030, where it will stabilize.[34] The Social Security Administration projects that an increase in payroll taxes equivalent to 1.9% of the payroll tax base or 0.7% of GDP would be necessary to put the Social Security program in fiscal balance for the next 75 years. Over an infinite time horizon, these shortfalls average 3.4% of the payroll tax base and 1.2% of GDP.[35] Various reforms have been debated for Social Security. Examples include reducing future annual cost of living adjustments (COLA) provided to recipients, raising the retirement age, and raising the income limit subject to the payroll tax ($106,800 in 2009).[36][37] Because of the mandatory nature of the program and large accumulated surplus in the Social Security Trust Fund, the Social Security system has the legal authority to compel the government to borrow to pay all promised benefits through 2037, when the Trust Fund is expected to be exhausted. Thereafter, the program under current law will pay approximately 75%-78% of promised benefits for the remainder of the century.[38]

Other spending

- Military spending: The military budget of the United States during FY 2009 was approximately $683 billion in expenses for the Department of Defense (DoD) and $54 billion for Homeland Security, a total of $737 billion.[39] The U.S. defense budget (excluding spending for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Homeland Security, and Veteran's Affairs) is around 4% of GDP.[40] Adding these other costs places defense and homeland security spending between 5% and 6% of GDP. The DoD baseline budget, excluding supplemental funding for the wars, has grown from $297 billion in FY2001 to a budgeted $534 billion for FY2010, an 81% increase.[41] According to the CBO, defense spending grew 9% annually on average from fiscal year 2000-2009.[42] Much of the costs for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have not been funded through regular appropriations bills, but through emergency supplemental appropriations bills. As such, most of these expenses were not included in the budget deficit calculation prior to FY2010. Some budget experts argue that emergency supplemental appropriations bills do not receive the same level of legislative care as regular appropriations bills.[43]

- Non-defense discretionary spending is used to fund the executive departments (e.g., the Department of Education) and independent agencies (e.g., the Environmental Protection Agency), although these do receive a smaller amount of mandatory funding as well. Discretionary budget authority is established annually by Congress, as opposed to mandatory spending that is required by laws that span multiple years, such as Social Security or Medicare. The Federal government spent approximately $660 billion during 2010 on the Cabinet Departments and Agencies, excluding the Department of Defense, representing 19% of budgeted expenditures[8] or about 4.5% of GDP. Several politicians and think tanks have proposed freezing non-defense discretionary spending at particular levels and holding this spending constant for various periods of time. President Obama proposed freezing discretionary spending representing approximately 12% of the budget in his 2011 State of the Union address.[44]

- Interest expense: Budgeted net interest on the public debt was approximately $189 billion in FY2009 (5% of spending). During FY2009, the government also accrued a non-cash interest expense of $192 billion for intra-governmental debt, primarily the Social Security Trust Fund, for a total interest expense of $381 billion.[45] Net interest costs paid on the public debt declined from $242 billion in 2008 to $189 billion in 2009 because of lower interest rates.[46] Should these rates return to historical averages, the interest cost would increase dramatically. Historian Niall Ferguson described the risk that foreign investors would demand higher interest rates as the U.S. debt levels increase over time in a November 2009 interview.[47] Public debt owned by foreigners has increased to approximately 50% of the total or approximately $3.4 trillion.[48] As a result, nearly 50% of the interest payments are now leaving the country, which is different from past years when interest was paid to U.S. citizens holding the public debt. Interest expenses are projected to grow dramatically as the U.S. debt increases and interest rates rise from very low levels in 2009 to more typical historical levels.

Understanding deficits and debt

The annual budget deficit is the difference between actual cash collections and budgeted spending (a partial measure of total spending) during a given fiscal year, which runs from October 1 to September 30. Since 1970, the U.S. Federal Government has run deficits for all but four years (1998–2001)[49] contributing to a total debt of $14.0 trillion as of December 2010.[50]

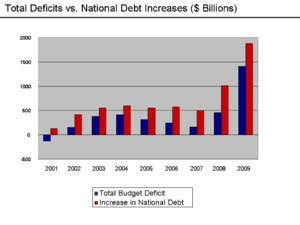

The U.S. Federal Government collected $2.52 trillion in FY2008, while budgeted spending was $2.98 trillion, generating a total deficit of $455 billion. However, during FY2008 the national debt increased by $1,017 billion, much more than the $455 billion deficit figure. This means actual expenditure was closer to $3.5 trillion (the $2.52 trillion in collections, all of which was spent, plus $1.0 trillion debt increase). The national debt represents the outstanding obligations of the government at any given time, comprising both public and intra-governmental debt. Differences between the annual deficit and annual change in the national debt include the treatment of the surplus Social Security payroll tax revenues (which increase the debt but not the deficit), supplemental appropriations for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and earmarks.

These differences can make it more challenging to determine how much the government actually spends relative to tax revenues. The increase in the national debt during a given year is a helpful measure to determine this amount. From FY 2003-2007, the national debt increased approximately $550 billion per year on average. For the first time in FY 2008, the U.S. added $1 trillion to the national debt.[51] In relative terms, from 2003-2007 the government spent roughly $1.20 for each $1.00 it collected in taxes. This increased to $1.40 in FY2008 and $1.90 in FY2009.

Social Security payroll taxes and benefit payments, along with the net balance of the U.S. Postal Service are considered "off-budget." Administrative costs of the Social Security Administration (SSA), however, are classified as "on-budget." In large part because of Social Security surpluses, the total federal budget deficit is smaller than the on-budget deficit. The surplus of Social Security payroll taxes over benefit payments is invested in special Treasury securities held by the Social Security Trust Fund. Social Security and other federal trust funds are part of the "intergovernmental debt." The total federal debt is divided into "intergovernmental debt" and "debt held by the public."

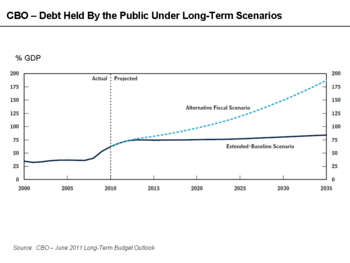

CBO Long-Term Scenarios

The CBO reported during June 2011 two scenarios for how debt held by the public will change during the 2010-2035 time period. The "extended baseline scenario" assumes that the Bush tax cuts (extended by Obama) will expire per current law in 2012. It also assumes the alternative minimum tax (AMT) will be allowed to affect more middle-class families, reductions in Medicare reimbursement rates to doctors will occur, and that revenues reach 23% GDP by 2035, much higher than the historical average 18%. Under this scenario, activities such as national defense and a wide variety of domestic programs (excluding Social Security, Medicare, and interest) would decline to the lowest percentage of GDP since before World War II. Under this scenario, public debt rises from 69% GDP in 2011 to 84% by 2035, with interest payments absorbing 4% of GDP vs. 1% in 2011.[52]

The "alternative fiscal scenario" more closely assumes the continuation of present trends, such as permanently extending the Bush tax cuts, restricting the reach of the AMT, and keeping Medicare reimbursement rates at the current level (the so-called "Doc Fix", versus declining by one-third as mandated under current law.) Revenues are assumed to remain around the historical average 18% GDP. Under this scenario, public debt rises from 69% GDP in 2011 to 100% by 2021 and approaches 190% by 2035.[53]

The CBO reported: "Many budget analysts believe that the alternative fiscal scenario presents a more realistic picture of the nation’s underlying fiscal policies than the extended-baseline scenario does. The explosive path of federal debt under the alternative fiscal scenario underscores the need for large and rapid policy changes to put the nation on a sustainable fiscal course."[54]

Contemporary issues and debates

Cause of decline in U.S. financial position

Both economic conditions and policy decisions significantly worsened the debt outlook since 2001, when large surpluses were forecast for the following decade by the CBO. The Pew Center reported in April 2011 the cause of a $12.7 trillion shift in the debt situation, from a 2001 CBO forecast of $2.3 trillion cumulative surplus by 2011 versus the estimated $10.4 trillion public debt in 2011. The major drivers were:

- Revenue declines due to two recessions, separate from the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003: 28%

- Defense spending increases: 15%

- Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003: 13%

- Increases in net interest: 11%

- Other non-defense spending: 10%

- Other tax cuts: 8%

- Obama Stimulus: 6%

- Medicare Part D: 2%

- Other reasons: 7%[55]

Similar analyses were reported by the New York Times in June 2009,[56] the Washington Post in April 2011[57] and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in May 2011.[58] Economist Paul Krugman wrote in May 2011: "What happened to the budget surplus the federal government had in 2000? The answer is, three main things. First, there were the Bush tax cuts, which added roughly $2 trillion to the national debt over the last decade. Second, there were the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which added an additional $1.1 trillion or so. And third was the Great Recession, which led both to a collapse in revenue and to a sharp rise in spending on unemployment insurance and other safety-net programs."[59] A Bloomberg analysis in May 2011 attributed $2.0 trillion of the $9.3 trillion of public debt (20%) to additional military and intelligence spending since September 2001, plus another $45 billion annually in interest.[60]

The extent to which the deficit and debt increases are a cause or effect of wider systemic problems is frequently debated. For example, in January 2008, then GAO Director David Walker pointed to four types of "deficits" that cause the overall fiscal problem: budget, trade, savings and leadership.[61]

Unemployment

CBO reported in 2009 that income tax revenues had declined by nearly 20% due to higher unemployment caused by the recession, while social safety net expenditures increased significantly.[62] The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) estimated in May 2010 that 15 million Americans were unemployed and another 11 million were involuntarily working part time or had dropped out of the labor force.[63] The U.S. labor force participation rate has declined from over 66% in 2007 to 64.2% in April 2011, while the ratio of civilians employed relative to the population has declined from over 63% in 2007 to 58.4%.[64] Unemployment is highly correlated with education levels. In April 2011, the unemployment rate was 4.5% for those with a college degree, 9.7% for high school graduates, and 14.6% for those without a high school diploma.[65]

Niall Ferguson estimated that excluding the effects of home equity withdrawal made possible by a U.S. housing bubble, the U.S. economy grew only 1% annually from 2001-2008.[66] The U.S. economy has historically required 2-4% annual growth (Okun's Law) to employ new workers entering the workforce, to prevent the unemployment rate from rising.[67] This implies that unemployment would have been growing since 2001 in the absence of the housing bubble, instead of suddenly rising in its wake. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers stated in July 2011: "Look, the most important determinant of where the deficit is going to be three, four years from now is how fast the economy grows. If the economy stagnates, no matter what we do with deficit deals, that deficit's going to be in a terrible place, and that's why growing the economy is so important."[68]

Wells Fargo Economics estimated in May 2011 that the structural unemployment rate (i.e., the rate unrelated to the business cycle) ranges between 6.3% to 7.1% and has risen due to the crisis. CBO estimates the structural rate around 5%. Factors affecting the structural rate of unemployment included: Education levels; rising costs of employee healthcare benefits; extension of unemployment benefits; reduced workforce mobility (i.e., ability to relocate to available jobs is reduced due to home price declines); and a skills mismatch (i.e., the skills of the unemployed do not match with open jobs). Structural unemployment is resistant to short-term monetary and fiscal policy solutions that work through the business cycle and has significant long-term impact on deficit and debt projections.[69] Mohamed El-Erian wrote in May 2011: "Unemployment must be seen as much more than a cyclical problem; it's a structural one that requires concurrent progress on job retraining, housing reform, education, social safety nets and private-sector competitiveness...America's political parties must jointly agree [to make] progress on the structural-reform agenda..."[70][71]

The McKinsey Global Institute reported in June 2011 that the U.S. economy was unlikely to return to a 5% unemployment rate prior to 2020. Further, the lag between GDP and employment returning to their pre-recession peaks has grown with recent recessions. This averaged around 6 months for 7 recessions between 1948-1981 but rose to 15 months in 1990 and 39 months in 2001. Between 2000 and 2007, the U.S. posted a weaker record of job creation than during any decade since the Great Depression, a total increase of 9.2 million jobs, less than half the rate of preceeding decades. Nearly 7 million net jobs have been lost since December 2007. To return to pre-recession employment levels by 2020, the U.S. economy would have to create 21 million net new jobs. This is roughly 187,000 jobs per month, versus 117,000 created on average during each of the first three months of 2011.[72]

Trade deficit and globalization

Imported goods are made by workers in other countries. The U.S. has a large current account or trade deficit, meaning its imports exceed exports. This also affects employment levels. In 2005, Ben Bernanke addressed the implications of the USA's high and rising current account deficit, which increased by $650 billion between 1996 and 2004, from 1.5% to 5.8% of GDP.[73] The trade deficit reached a dollar peak of approximately $700 billion in 2008 (4.9% of GDP) before dropping to $420 billion in 2009 (2.9% of GDP) due to the 2009 recession.[74] The trade deficit was $500 billion in 2010, with a goods deficit of $650 billion offset by a services surplus of $150 billion.[75]

China's share of global manufacturing increased from approximately 5% in 1996 to 12% in 2008. China represents roughly one-third of the U.S. trade deficit, nearly $250 billion in 2008.[76] The Economic Policy Institute estimated U.S. job losses due to the trade deficit with China alone at 2.3 million jobs between 2001 and 2007, along with significantly lowered U.S. wages.[77] USA Today reported in 2007 that an estimated one in six factory jobs (3.2 million) have disappeared from the U.S. since 2000, due to automation or off-shoring to countries like Mexico and China, where labor is cheaper. The Economist reported in March 2011 that U.S. manufacturing employment declined steadily from approximately 17 million in 2000 to under 12 million in 2010.[78]

These lost manufacturing jobs are fueling a debate over globalization -- the increasing connection of the United States and other economies. An estimated 84% of Americans in the labor force are employed in service jobs, up from 81% in 2000. Princeton economist Alan Blinder said in 2007 that the number of jobs at risk of being shipped out of the country could reach 40 million over the next 10 to 20 years. That would be one out of every three service sector jobs that could be at risk.[79] Since the early 1980s, the globalization of production and the growth of markets abroad have driven many firms to locate production closer to their customers. Moreover, the push for competitiveness and productivity has meant more automation (i.e., capital instead of labor) to improve the efficiency of production.[80]

A popular product, the Apple iPod, offers an interesting perspective on globalization and employment. This product was developed by a U.S. corporation. In 2006, it was produced by about 14,000 workers in the U.S. and 27,000 overseas. Further, the salaries attributed to this product were overwhelmingly distributed to highly skilled U.S. professionals, as opposed to lower skilled U.S. retail employees or overseas manufacturing labor. Increasingly, globalization is shifting incomes to those with the highest educational backgrounds and professional skills. One interpretation of this result is that U.S. innovation can create more jobs overseas than domestically.[81]

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in 2007: "For the world economy as a whole — and especially for poorer nations — growing trade between high-wage and low-wage countries is a very good thing...But for American workers the story is much less positive. In fact, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that growing U.S. trade with third world countries reduces the real wages of many and perhaps most workers in this country...The trouble now is that these effects may no longer be as modest as they were, because imports of manufactured goods from the third world have grown dramatically — from just 2.5 percent of GDP in 1990 to 6 percent in 2006."[82]

Former Fed chair Paul Volcker argued in February 2010 that the U.S. should make more of the goods it consumes domestically: "We need to do more manufacturing again. We're never going to be the major world manufacturer as we were some years ago, but we could do more than we're doing and be more competitive. And we've got to close that big gap. You know, consumption is running about 5 percent above normal. That 5 percent is reflected just about equally to what we're importing in excess of what we're exporting. And we've got to bring that back into closer balance."[83]

Policies that affect the value of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies also affect employment levels. Economist Christina Romer wrote in May 2011: "A weaker dollar means that our goods are cheaper relative to foreign goods. That stimulates our exports and reduces our imports. Higher net exports raise domestic production and employment. Foreign goods are more expensive, but more Americans are working. Given the desperate need for jobs, on net we are almost surely better off with a weaker dollar for a while."[84] Economist Paul Krugman wrote in May 2011: "First, what’s driving the turnaround in our manufacturing trade? The main answer is that the U.S. dollar has fallen against other currencies, helping give U.S.-based manufacturing a cost advantage. A weaker dollar, it turns out, was just what U.S. industry needed."[85]

Budgetary impact of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts

A variety of tax cuts were enacted under President Bush between 2001–2003 (commonly referred to as the "Bush tax cuts"), through the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA) and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA). Most of these tax cuts were scheduled to expire December 31, 2010. Since CBO projections are based on current law, the projections discussed above assume these tax cuts will expire, which may prove politically challenging.

In August 2010, CBO estimated that extending the tax cuts for the 2011-2020 time period would add $3.3 trillion to the national debt: $2.65 trillion in foregone tax revenue plus another $0.66 trillion for interest and debt service costs.[86]

The non-partisan Pew Charitable Trusts estimated in May 2010 that extending some or all of the Bush tax cuts would have the following impact under these scenarios:

- Making the tax cuts permanent for all taxpayers, regardless of income, would increase the national debt $3.1 trillion over the next 10 years.

- Limiting the extension to individuals making less than $200,000 and married couples earning less than $250,000 would increase the debt about $2.3 trillion in the next decade.

- Extending the tax cuts for all taxpayers for only two years would cost $558 billion over the next 10 years.[87]

The non-partisan Congressional Research Service (CRS) has reported the 10-year revenue loss from extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts beyond 2010 at $2.9 trillion, with an additional $606 billion in debt service costs (interest), for a combined total of $3.5 trillion. CRS cited CBO estimates that extending the cuts permanently, including the repeal of the estate tax, would add 2% of GDP to the annual deficit.[88]

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities wrote in 2010: "The 75-year Social Security shortfall is about the same size as the cost, over that period, of extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts for the richest 2 percent of Americans (those with incomes above $250,000 a year). Members of Congress cannot simultaneously claim that the tax cuts for people at the top are affordable while the Social Security shortfall constitutes a dire fiscal threat."[89]

Can reducing income tax rates increase government revenue?

In theory, the government collects no revenue at either zero or 100% tax rates. So there is some intermediate point at which government revenue is maximized. Lowering tax rates from 100% to this hypothetical rate that maximizes revenue would theoretically raise revenue, while continuing to lower tax rates below this rate would lower revenues. This concept underlies the Laffer Curve, an element of supply-side economics.

Since the 1970s, some "supply side" economists have contended that lowering marginal tax rates could stimulate economic growth to such a degree that tax revenues could rise, other factors being held constant. However, economic models and econometric analysis have found weak support for the "supply side" theory. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) summarized a variety of studies done by economists across the political spectrum that indicated tax cuts do not pay for themselves and increase deficits.[90] Studies by the CBO and the U.S. Treasury also indicated that tax cuts do not pay for themselves.[91][92][93][94] In 2003, 450 economists, including ten Nobel Prize laureate, signed the Economists' statement opposing the Bush tax cuts, sent to President Bush stating that "these tax cuts will worsen the long-term budget outlook... will reduce the capacity of the government to finance Social Security and Medicare benefits as well as investments in schools, health, infrastructure, and basic research... [and] generate further inequalities in after-tax income."[95]

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in 2007: "Supply side doctrine, which claimed without evidence that tax cuts would pay for themselves, never got any traction in the world of professional economic research, even among conservatives."[96] Economist Nouriel Roubini wrote in October 2010 that the Republican Party was "trapped in a belief in voodoo economics, the economic equivalent of creationism" while the Democratic administration was unwilling to improve the tax system via a carbon tax or value-added tax.[97] Warren Buffett wrote in 2003: "When you listen to tax-cut rhetoric, remember that giving one class of taxpayer a 'break' requires -- now or down the line -- that an equivalent burden be imposed on other parties. In other words, if I get a break, someone else pays. Government can't deliver a free lunch to the country as a whole."[98] Former Comptroller General of the United States David Walker stated during January 2009: "You can't have guns, butter and tax cuts. The numbers just don't add up."[99]

Income tax revenues generally rose to new peaks in nominal dollar terms each year from 1970 to 2000 as the economy grew, with the exception of 1983, following the recession of 1981-1982. However, after peaking in 2000, income tax revenues did not regain this peak again until 2006. After a plateau in 2007 and 2008, revenues fell markedly in 2009 and 2010 due to a financial crisis and recession. Income tax revenues in 2010 remained below their 2000 peak. Relative to GDP, income tax revenues declined during most of the 1980's (from 9.0% GDP in 1980 to 8.3% GDP in 1989), rose during most of the 1990's (from 8.1% GDP in 1990 to 9.6% GDP in 1999) then declined in the 2000's (from 10.2% GDP in 2000 to 6.5% GDP in 2009).[100] The extent to which economic activity and tax policy interact to drive these trends is debated by experts. While marginal income tax rates were lowered in the early 1980's, dollar revenue increased throughout the period, although revenue relative to GDP declined. Marginal tax rates were raised during the 1990's, and both revenue dollars and revenue relative to GDP increased. Marginal rates were lowered again in the early 2000's, and both revenue and revenue relative to GDP generally declined.

Can increasing tax receipts alone address the budget deficit?

Expert panels across the political spectrum have argued for a combination of revenue increases and expense reductions to reduce the budget deficit and future debt increases. However, the nature and balance of these measures varies considerably.[101] Economist Bruce Bartlett wrote in 2009 that without benefit cuts in Medicare and Social Security, federal taxes would have to increase by 8.1% of GDP now and forever to cover estimated program shortfalls, while avoiding debt increases.[102] The 30-year historical average federal tax receipts are 18.4% of GDP, so this would represent a substantial increase in tax receipts as a share of GDP relative to historical levels in the United States. However, such an increase would still leave tax revenues relative to GDP substantially lower than other developed nations like France and Germany (see: List of countries by tax revenue as percentage of GDP).

Can the U.S. outgrow the problem?

There is debate regarding whether tax cuts, less intrusive regulation, and productivity improvements could feasibly generate sufficient economic growth to offset the deficit and debt challenges facing the country. According to David Stockman, OMB Director under President Reagan, post-1980 Republican ideology embraces the idea that the "economy will outgrow the deficit if plied with enough tax cuts."[103] Former President George W. Bush exemplified this ideology when he wrote in 2007: "...it is also a fact that our tax cuts have fueled robust economic growth and record revenues."[104] However, as described in the tax policy section of this article, multiple studies by economists across the political spectrum and several government organizations argue that tax cuts increase deficits and debt.[90][105]

The GAO estimated in 2008 that double-digit GDP growth would be required for the next 75 years to outgrow the projected increases in deficits and debt; GDP growth averaged 3.2% during the 1990s. Because mandatory spending growth rates will far exceed any reasonable growth rate in GDP and the tax base, the GAO concluded that the U.S. cannot grow its way out of the problem.[106]

Fed Chair Ben Bernanke stated in April 2010: "Unfortunately, we cannot grow our way out of this problem. No credible forecast suggests that future rates of growth of the U.S. economy will be sufficient to close these deficits without significant changes to our fiscal policies."[107]

Stimulus packages

The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 provided an estimated $170 billion in tax rebates to stimulate the economy. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the Act "would increase budget deficits (or reduce future surpluses) by $152 billion in 2008 and by a net amount of $124 billion over the 2008-2018 period."[108]

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 was passed by the U.S. Congress on 13 February 2009. The nearly $800 billion bill appropriated money toward tax credits and infrastructure programs. The CBO estimates that enacting the bill would increase federal budget deficits by $185 billion over the remaining months of fiscal year 2009, by $399 billion in 2010, by $134 billion in 2011, and by $787 billion over the 2009-2019 period.[109]

Stimulus can be characterized as investment, spending or tax cuts. For example, if the funds are used to create a physical asset that generates future cash flows (e.g., a power plant or toll road), the stimulus could be characterized as investment. Extending unemployment benefits are examples of government spending. Tax cuts may or may not be spent. There is significant debate among economists regarding which type of stimulus has the highest "multiplier" (i.e., increase in economic activity per dollar of stimulus).[110]

Earmarks

GAO defines "earmarking" as "designating any portion of a lump-sum amount for particular purposes by means of legislative language." Earmarking can also mean "dedicating collections by law for a specific purpose." [111] In some cases, legislative language may direct federal agencies to spend funds for specific projects. In other cases, earmarks refer to directions in appropriation committee reports, which are not law. Various organizations have estimated the total number and amount of earmarks. An estimated 16,000 earmarks containing nearly $48 billion in spending were inserted into larger, often unrelated bills during 2005.[112] While the number of earmarks has grown in the past decade, the total amount of earmarked funds is approximately 1-2 percent of federal spending.[113]

Fraud, waste and abuse

The Office of Management and Budget estimated that the federal government made $98 billion in "improper payments" during FY2009, an increase of 38% vs. the $72 billion the prior year. This increase was due in part to effects of the financial crisis and improved methods of detection. The total included $54 billion for healthcare-related programs, 9.4% of the $573 billion spent on those programs. The government pledged to do more to combat this problem, including better analysis, auditing, and incentives.[114][115] During July 2010, President Obama signed into law the Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Act of 2010, citing approximately $110 billion in unauthorized payments of all types.[116]

Former GAO Director David Walker said: "Some people think that we can solve our financial problems by stopping fraud, waste and abuse or by canceling the Bush tax cuts or by ending the war in Iraq. The truth is, we could do all three of these things and we would not come close to solving our nation's fiscal challenges."[117]

2010 Budget Proposal

President Barack Obama proposed his 2010 budget during February, 2009. He has indicated that health care, clean energy, education, and infrastructure will be priorities. The proposed increases in the national debt exceed $900 billion each year from 2010–2019, following the Bush administration's outgoing budget which allowed for a $2.5 trillion increase in the national debt for FY 2009.[118]

Tax cuts will expire for the wealthiest taxpayers to increase revenues, returning marginal rates to the Clinton levels. Further, the base Department of Defense budget increases slightly through 2014 (Table S-7), from $534 to $575 billion, although supplemental appropriations for the Iraq War are expected to be reduced. In addition, estimates of revenue are based on GDP growth assumptions that exceed the Blue Chip Economists' consensus forecast considerably through 2012 (Table S-8).[119][120]

2010 Healthcare reform

The CBO estimated in December 2009 that the Senate healthcare reform bill, later signed into law on 23 March 2010, would reduce the deficit during the 2010-2019 period by a total of $132 billion. This figure comprises $615 billion in incremental costs, offset by cost reductions of $483 billion and additional taxes of $264 billion. The CBO also estimated that the deficit would be about 0.5% lower each year in the 2020-2029 decade, or about $70 billion annually in 2010 dollars.[121] Whether the deficit reduction will materialize is questioned by many budget experts.[122]

State finances

The U.S. federal government may be required to assist state governments further, as many U.S. states are facing budget shortfalls due to the 2008-2010 recession. The sharp decline in home prices has affected property tax revenue, while the decline in economic activity and consumer spending has led to a falloff in revenues from state sales taxes and income taxes. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated that the 2010 and 2011 state shortfalls will total $375 billion.[123] As of July 2010, over 30 states had raised taxes, while 45 had reduced services.[124] State and local governments cut 405,000 jobs between January 2009 and February 2011.[125]

GAO estimates that (absent policy changes) state and local governments will face budget gaps that rise from 1% of GDP in 2010 to around 2% by 2020, 2.5% by 2030, and 3.5% by 2040.[126]

Further, many states have underfunded pensions, meaning the state has not contributed the amount estimated to be necessary to pay future obligations to retired workers. The Pew Center on the States reported in February 2010 that states have underfunded their pensions by nearly $1 trillion as of 2008, representing the gap between the $2.35 trillion states had set aside to pay for employees’ retirement benefits and the $3.35 trillion price tag of those promises.[127]

Whether a U.S. state can declare bankruptcy, enabling it to re-negotiate its obligations to bondholders, pensioners, and public employee unions is a matter of legal and political debate. Journalist Matt Miller explained some of these issues in February 2011: "The AG [State Attorney General] might put a plan forward and agree to conditions. However, the AG has no say over the legislature. And only a legislature can raise taxes. In some cases, it would require a state constitutional amendment to reduce pensions. Add to this a federal judge who would oversee the process...and a state has sovereign immunity, which means the governor or legislature may simply refuse to go along with anything the judge rules or reject the reorganization plan itself."[128]

Implications of entitlement trust funds

Both Social Security and Medicare are funded by payroll tax revenues dedicated to those programs. Program tax revenues historically have exceeded payouts, resulting in program surpluses and the building of trust fund balances. The trust funds earn interest. Both Social Security and Medicare each have two component trust funds. As of FY2008, Social Security had a combined $2.4 trillion trust fund balance and Medicare's was $380 billion. If during an individual year program payouts exceed the sum of tax income and interest earned during that year (i.e., an annual program deficit), the trust fund for the program is drawn down to the extent of the shortfall. Legally, the mandatory nature of these programs compels the government to fund them to the extent of tax income plus any remaining trust fund balances, borrowing as needed. Once the trust funds are eliminated through expected future deficits, technically these programs can only draw on payroll taxes during the current year. In effect, they are "pay as you go" programs, with additional legal claims to the extent of their remaining trust fund balances.[129]

There are no actual trust funds for either Social Security or Medicare. During the administration of Lyndon B Johnson, these "trust funds" have been trust funds in name-only. The revenues of these programs go directly into the general coffers and all the funds have been spent, every year since. Presently, there are nothing but non-marketable treasury securities or "IOU's" in the Trust Funds.

A "spending problem" or a "revenue problem"?

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2011) |

Republican Congressman and Speaker of the House John Boehner stated: "Washington has a spending problem, not a revenue problem" in April 2011.[130] Variations on this statement have been made by other Republicans, such as House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, who stated: "Most people understand that Washington doesn't have a revenue problem, it has a spending problem" and adding "We can't raise taxes."[131] President Obama has proposed that the Bush tax cuts should be allowed to expire for the wealthiest taxpayers,[132] while Alan Greenspan has proposed that these tax cuts should expire at all income levels.[133]

Near-term

Taking the last balanced "total" budget in 2001 as a standard, spending has risen by 5.6% GDP, from 18.2% GDP in 2001 to 23.8% GDP in 2010, while revenues declined by 4.6% GDP, from 19.5% GDP to 14.9% GDP over the same interval. By this measure, spending has increased about 1% GDP more than revenues have declined. Using the historical (1971-2008) average spending of 20.6% GDP and revenues of 18.2%, the spending increase of 3.2% GDP is smaller than the revenue decline of 3.3% GDP. In other words, the "spending problem" and "revenue problem" are comparable in size.[134]

However, the first family of numbers, showing an apparent "spending problem", is potentially misleading for a number of reasons. First and foremost, a good deal of the increase in spending relative to GDP may be attributable to below-trend growth, as Medicare, Medicaid, and military spending increases are not indexed to GDP growth. Also of comparable gravity is the high level of unemployment leading to large numbers of claims for unemployment insurance and other safety net spending.[135][136]

The second family of numbers, showing the apparent "revenue problem", is, in stark contrast with the first family, not misleading, simply because tax receipts are, keeping all other variables constant, directly proportional to GDP. That is, in any reasonable circumstance, the amount of revenue as a fraction of GDP depends only on tax policy, not on the absolute level of GDP.[citation needed]

It follows from the simple arithmetic of the above argument that while a substantial amount of the evident spending problem will vanish upon the economy's eventual return to trend GDP, the revenue problems may remain despite a recovery unless action is taken by the Federal government to increase tax receipts relative to GDP.[citation needed]

Long-term

In the long-run, Medicare and Medicaid are projected to increase dramatically relative to GDP, while other categories of spending are expected to remain relatively constant. The Congressional Budget Office expects Medicare and Medicaid to rise from 5.3% GDP in 2009 to 10.0% in 2035 and 19.0% by 2082. CBO has indicated healthcare spending per beneficiary is the primary long-term fiscal challenge. So in the long-run, spending on these programs is the key issue, far outweighing any revenue consideration.[31][102] Economist Paul Krugman has made the argument that any serious attempt to tackle long-run deficit problems can be summed up in "seven words: health care, health care, health care, revenue."[137]

Deficit

Describing the budgetary challenge

Then OMB Director Peter Orszag stated in a November 2009 interview: "It's very popular to complain about the deficit, but then many of the specific steps that you could take to address it are unpopular. And that is the fundamental challenge that we are facing, and that we need help both from the American public and Congress in addressing." He characterized the budget problem in two parts: a short- to medium-term problem related to the financial crisis of 2007–2010, which has reduced tax revenues significantly and involved large stimulus spending; and a long-term problem primarily driven by increasing healthcare costs per person. He argued that the U.S. cannot return to a sustainable long-term fiscal path by either tax increases or cuts to non-healthcare cost categories alone; the U.S. must confront the rising healthcare costs driving expenditures in the Medicare and Medicaid programs.[138]

Fareed Zakaria said in February 2010: "But, in one sense, Washington is delivering to the American people exactly what they seem to want. In poll after poll, we find that the public is generally opposed to any new taxes, but we also discover that the public will immediately punish anyone who proposes spending cuts in any middle class program which are the ones where the money is in the federal budget. Now, there is only one way to square this circle short of magic, and that is to borrow money, and that is what we have done for decades now at the local, state and federal level...So, the next time you accuse Washington of being irresponsible, save some of that blame for yourself and your friends."[139]

Andrew Sullivan said in March 2010: "...the biggest problem in this country is...they're big babies. I mean, people keep saying they don't want any tax increases, but they don't want to have their Medicare cut, they don't want to have their Medicaid [cut] or they don't want to have their Social Security touched an inch. Well, it's about time someone tells them, you can't have it, baby...You have to make a choice. And I fear that—and I always thought, you see, that that was the Conservative position. The Conservative is the Grinch who says no. And, in some ways, I think this in the long run, looking back in history, was Reagan's greatest bad legacy, which is he tried to tell people you can have it all. We can't have it all."[140]

Harvard historian Niall Ferguson stated in a November 2009 interview: "The United States is on an unsustainable fiscal path. And we know that path ends in one of two ways; you either default on that debt, or you depreciate it away. You inflate it away with your currency effectively." He said the most likely case is that the U.S. would default on its entitlement obligations for Social Security and Medicare first, by reducing the obligations through entitlement reform. He also warned about the risk that foreign investors would demand a higher interest rate to purchase U.S. debt, damaging U.S. growth prospects.[141]

The CBO reported several types of risk factors related to rising debt levels in a July 2010 publication:

- A growing portion of savings would go towards purchases of government debt, rather than investments in productive capital goods such as factories and computers, leading to lower output and incomes than would otherwise occur;

- If higher marginal tax rates were used to pay rising interest costs, savings would be reduced and work would be discouraged;

- Rising interest costs would force reductions in important government programs;

- Restrictions to the ability of policymakers to use fiscal policy to respond to economic challenges; and

- An increased risk of a sudden fiscal crisis, in which investors demand higher interest rates.[142]

In April 2011, rating agency Standard & Poor's (S&P) issued a "negative" outlook on the U.S. "AAA" (highest quality) debt rating for the first time since the rating agency began in 1860, indicating there is a one in three chance of an outright reduction in the rating over the next two years. According to S&P, meaningful progress towards balancing the budget would be required to move the U.S. back to a "stable" outlook. Losing the AAA rating would likely mean higher interest rates and the sale of treasury bonds by entities required to hold AAA securities.[143] The S&P press release stated: "We believe there is a material risk that U.S. policymakers might not reach an agreement on how to address medium- and long-term budgetary challenges by 2013; if an agreement is not reached and meaningful implementation is not begun by then, this would in our view render the U.S. fiscal profile meaningfully weaker than that of peer 'AAA' sovereigns."[144]

Polls

According to a CBS News/New York Times poll in July 2009, 56% of people were opposed to paying more taxes to reduce the deficit and 53% were also opposed to cutting spending. According to a Pew Research poll in June 2009, there was no single category of spending that a majority of Americans favored cutting. Only cuts in foreign aid (less than 1% of the budget), polled higher than 33%. Economist Bruce Bartlett wrote in December 2009: "Nevertheless, I can't really blame members of Congress for lacking the courage or responsibility to get the budget under some semblance of control. All the evidence suggests that they are just doing what voters want them to do, which is nothing."[145]

A Bloomberg/Selzer national poll conducted in December 2009 indicated that more than two-thirds of Americans favored tax increases on the rich (individuals making over $500,000) to help solve the deficit problem. Further, an across-the-board 5% cut in all federal discretionary spending would be supported by 57%; this category is about 30% of federal spending. Only 26% favored tax increases on the middle class and only 23% favored reducing the growth rate in entitlements, such as Social Security.[146][147]

A Rasmussen Reports survey in February 2010 showed that only 35% of voters correctly believe that the majority of federal spending goes to just defense, Social Security and Medicare. Forty-four percent (44%) say it’s not true, and 20% are not sure. [148] A January 2010 Rasmussen report showed that overall, 57% would like to see a cut in government spending, 23% favor a freeze, and 12% say the government should increase spending. Republicans and unaffiliated voters overwhelmingly favor spending cuts. Democrats are evenly divided between spending cuts and a spending freeze.[149]

According to a Pew Research poll in March 2010, 31% of Republicans would be willing to decrease military spending to bring down the deficit. A majority of Democrats (55%) and 46% of Independents say they would accept cuts in military spending to reduce the deficit.[150]

Proposed solutions

Solution strategies

In January 2008, then GAO Director David Walker presented a strategy for addressing what he called the federal budget "burning platform" and "unsustainable fiscal policy." This included improved financial reporting to better capture the obligations of the government; public education; improved budgetary and legislative processes, such as "pay as you go" rules; the restructure of entitlement programs and tax policy; and creation of a bi-partisan fiscal reform commission. He pointed to four types of "deficits" that make up the problem: budget, trade, savings and leadership.[151]

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in February 2011: "What would a serious approach to our fiscal problems involve? I can summarize it in seven words: health care, health care, health care, revenue...Long-run projections suggest that spending on the major entitlement programs will rise sharply over the decades ahead, but the great bulk of that rise will come from the health insurance programs, not Social Security. So anyone who is really serious about the budget should be focusing mainly on health care...[by] getting behind specific actions to rein in costs."[152]

Economist Nouriel Roubini wrote in May 2010: "There are only two solutions to the sovereign debt crisis — raise taxes or cut spending — but the political gridlock may prevent either from happening...In the US, the average tax burden as a share of GDP is much lower than in other advanced economies. The right adjustment for the US would be to phase in revenue increases gradually over time so that you don't kill the recovery while controlling the growth of government spending."[153]

David Leonhardt wrote in The New York Times in March 2010: "For now, political leaders in both parties are still in denial about what the solution will entail. To be fair, so is much of the public. What needs to happen? Spending will need to be cut, and taxes will need to rise. They won’t need to rise just on households making more than $250,000, as Mr. Obama has suggested. They will probably need to rise on your household, however much you make...A solution that relied only on spending cuts would dismantle some bedrock parts of modern American society...A solution that relied only on taxes would muzzle economic growth."[154]

Fed Chair Ben Bernanke stated in April 2010: "Thus, the reality is that the Congress, the Administration, and the American people will have to choose among making modifications to entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security, restraining federal spending on everything else, accepting higher taxes, or some combination thereof."[107]

Journalist Steven Pearlstein argued in May 2010 for a comprehensive series of budgetary reforms. These included: Spending caps on Medicare and Medicaid; gradually raising the eligibility age for Social Security and Medicare; limiting discretionary spending increases to the rate of inflation; and imposing a value-added tax.[155]

National Research Council strategies

During January 2010, the National Research Council and the National Academy of Public Administration reported a series of strategies to address the problem. They included four scenarios designed to prevent the public debt to GDP ratio from exceeding 60%:

- Low spending and low taxes. This path would allow payroll and income tax rates to remain roughly unchanged, but it would require sharp reductions in the projected growth of health and retirement programs; defense and domestic spending cuts of 20 percent; and no funds for any new programs without additional spending cuts.

- Intermediate path 1. This path would raise income and payroll tax rates modestly. It would allow for some growth in health and retirement spending; defense and domestic program cuts of 8 percent; and selected new public investments, such as for the environment and to promote economic growth.

- Intermediate path 2. This path would raise income and payroll taxes somewhat higher than with the previous path. Spending growth for health and retirement programs would be slowed, but less than under the other intermediate path; and spending for all other federal responsibilities would be reduced. This path gives higher priority to entitlement programs for the elderly than to other types of government spending.

- High spending and taxes. This path would require substantially higher taxes. It would maintain the projected growth in Social Security benefits for all future retirees and require smaller reductions over time in the growth of spending for health programs. It would allow spending on all other federal programs to be higher than the level implied by current policies.[156][157]

CBO budget options reports

The CBO provides a report discussing the cost and revenue impact of various budget options annually.[158] The CBO also estimated in 2007 that allowing the 2001 and 2003 income tax cuts to expire on schedule in 2010 would reduce the annual deficit by $200–300 billion.[159] In addition, CBO reported that annual defense spending has increased from approximately $300 billion in 2001 (when the budget was last balanced) to $650 billion in 2009.[160]

Republican proposals

Rep. Paul Ryan (R) has proposed the Roadmap for America's Future, which is a series of budgetary reforms. His January 2010 version of the plan includes partial privatization of Social Security, the transition of Medicare to a voucher system, discretionary spending cuts and freezes, and tax reform.[161] A series of graphs and charts summarizing the impact of the plan are included.[162] Economists have both praised and criticized particular features of the plan.[163][164] The CBO also did a partial evaluation of the bill.[165] The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) was very critical of the Roadmap.[166] Rep. Ryan provided a response to the CBPP's analysis.[167]

The House of Representatives Committee on the Budget, chaired by Paul Ryan, released a budget resolution in April 2011, titled The Path to Prosperity: Restoring America's Promise. The Path focuses on tax reform (lowering income tax rates and reducing tax expenditures or loopholes); spending cuts and controls; and redesign of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. It does not propose significant changes to Social Security.[168] The CBO did an analysis of the resolution (a less rigorous evaluation than full scoring of legislation), estimating that the Path would balance the budget by 2030 and reduce the level of debt held by the public to 10% GDP by 2050, vs. 62% in 2010. The Path assumes revenue collection of 19% GDP after 2022, up from the current 15% GDP and closer to the historical average of 18.3% GDP. A grouping of spending categories called "Other Mandatory and Defense and Non-Defense Discretionary spending" would be reduced from 12% GDP in 2010 to 3.5% by 2050.[169] Economist Paul Krugman called it "ridiculous and heartless" due to a combination of income tax rate reductions (which he argued mainly benefit the wealthy) and large spending cuts that would affect the poor and middle classes.[170][171]

The Republican Party website includes an alternative budget proposal provided to the President in January 2010. It includes lower taxes, lower annual increases in entitlement spending growth, and marginally higher defense spending than the President's 2011 budget proposal.[172] During September 2010, Republicans published "A Pledge to America" which advocated a repeal of recent healthcare legislation, reduced spending and the size of government, and tax reductions.[173] The NYT editorial board was very critical of the Pledge, stating: "...[The Pledge] offers a laundry list of spending-cut proposals, none of which are up to the scale of the problem, and many that cannot be taken seriously."[174]

Fiscal reform commission

President Obama established a budget reform commission, the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, during February, 2010. The Commission "shall propose recommendations designed to balance the budget, excluding interest payments on the debt, by 2015. This result is projected to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at an acceptable level once the economy recovers." The Commission's released its final report in December 2010.[175]

The Commission released a draft of its proposals on November 10, 2010. It included various tax and spend adjustments to bring long-run government tax revenue and spending into line at approximately 21% of GDP. For fiscal year 2009, tax revenues were approximately 15% of GDP and spending was 24% of GDP. The Co-chairs summary of the plan states that it:

- Achieves nearly $4 trillion in deficit reduction through 2020 via 50+ specific ways to cut outdated programs and strengthen competitiveness by making Washington cut and invest, not borrow and spend.

- Reduces the deficit to 2.2% of GDP by 2015, exceeding President’s goal of primary balance (about 3% of GDP).

- Reduces tax rates, abolishes the alternative minimum tax, and cuts backdoor spending (e.g., mortgage interest deductions) in the tax code.

- Stabilizes debt by 2014 and reduces debt to 60% of GDP by 2024 and 40% by 2037.

- Ensures lasting Social Security solvency, prevents projected 22% cuts in 2037, reduces elderly poverty, and distributes burden fairly.[176]

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities evaluated the draft plan, praising that it "puts everything on the table" but criticizing that it "lacks an appropriate balance between program cuts and revenue increases."[177]

President Obama's proposal

President Obama outlined his strategy for reducing future deficits in April 2011 and explained why this debate is important: "...as the Baby Boomers start to retire in greater numbers and health care costs continue to rise, the situation will get even worse. By 2025, the amount of taxes we currently pay will only be enough to finance our health care programs -- Medicare and Medicaid -- Social Security, and the interest we owe on our debt. That’s it. Every other national priority -– education, transportation, even our national security-–will have to be paid for with borrowed money." He warned that interest payments may reach $1 trillion annually by the end of the decade.

He outlined core principles of his proposal, which includes investments in key areas while reducing future expenditures. "I will not sacrifice the core investments that we need to grow and create jobs. We will invest in medical research. We will invest in clean energy technology. We will invest in new roads and airports and broadband access. We will invest in education. We will invest in job training. We will do what we need to do to compete, and we will win the future." He outlined his proposals for reducing future deficits, by:

- Reducing non-defense discretionary spending, by freezing or limiting increases in future spending;

- Finding savings in the defense budget, building on $400 billion in savings already identified by Defense Secretary Gates;

- Reducing healthcare spending, by reducing subsidies and erroneous payments, negotiating for lower prescription drug prices and use of generics, improving efficiencies in the Medicaid program, altering doctor incentives, and empowering a panel of experts to recommend cost-effective treatments and solutions;

- Strengthening the Social Security program, without reducing commitments to current or future retirees (by implication revenue increases); and

- Raising revenues, primarily by raising taxes on the wealthy and reducing certain types of tax expenditures.[132]

On June 23, at a hearing of the Budget Committee, CBO director Douglas Elmendorf was asked what his agency made of the proposals in that presidential address. “We don’t estimate speeches,” he said. “We need much more specificity than was provided in that speech."[178]

President Obama's actual 2012 budget proposal was defeated in the Senate by a margin of 0-97 votes. [179]

Congressional Progressive Caucus "The People's Budget"