PC game: Difference between revisions

m MOS:DASH using script, align date formats using script]], redress overlinking using script |

|||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

=== Contemporary gaming === |

=== Contemporary gaming === |

||

By 1996, the rise of [[Microsoft Windows]] and success of 3D console titles such as ''[[Super Mario 64]]'' sparked great interest in [[3D acceleration|hardware accelerated 3D graphics]] on the [[IBM PC compatible]], and soon resulted in attempts to produce affordable solutions with the [[ATI Technologies|ATI]] ''Rage'', [[Matrox]] ''Mystique'' and [[S3 ViRGE]]. [[Tomb Raider]], which was released in 1996, was one of the first |

By 1996, the rise of [[Microsoft Windows]] and success of 3D console titles such as ''[[Super Mario 64]]'' sparked great interest in [[3D acceleration|hardware accelerated 3D graphics]] on the [[IBM PC compatible]], and soon resulted in attempts to produce affordable solutions with the [[ATI Technologies|ATI]] ''Rage'', [[Matrox]] ''Mystique'' and [[S3 ViRGE]]. ''[[Tomb Raider]]'', which was released in 1996, was one of the first 3D [[third-person shooter]] games and was praised for its revolutionary graphics. As 3D graphics libraries such as [[DirectX]] and [[OpenGL]] matured and knocked proprietary interfaces out of the market, these platforms gained greater acceptance in the market, particularly with their demonstrated benefits in games such as ''[[Unreal]]''.<ref name="unreal">Shamma, Tahsin. [http://www.gamespot.com/pc/action/unreal/review.html Review of Unreal], Gamespot.com, June 10, 1998.</ref> However, major changes to the [[Microsoft Windows]] operating system, by then the market leader, made many older [[MS-DOS]]-based games unplayable on [[Windows NT]], and later, [[Windows XP]] (without using an [[emulator]], such as [[DOSbox]]).<ref name="dosincompatibility">{{cite web|url=http://www.microsoft.com/windowsxp/using/games/expert/durham_og.mspx|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20070420123928/http://www.microsoft.com/windowsxp/using/games/expert/durham_og.mspx|archivedate=April 20, 2007 |title=Getting Older Games to Run on Windows XP |accessdate=September 22, 2006 |last=Durham, Jr. |first=Joel |date=May 14, 2006}}</ref><ref>[http://www.microsoft.com/windowsxp/using/helpandsupport/learnmore/appcompat.mspx Run Older Programs on Windows XP]</ref> |

||

The faster graphics accelerators and improving [[Central processing unit|CPU]] technology resulted in increasing levels of realism in computer games. During this time, the improvements introduced with products such as ATI's [[Radeon R300]] and [[NVidia]]'s [[GeForce 6 Series]] have allowed developers to increase the complexity of modern [[game engine]]s. PC gaming currently tends strongly toward improvements in 3D graphics.<ref name="graphicstrend">{{cite web|url=http://www.justadventure.com/articles/3D/3DGraphicsTrens.shtm |title=Brief Glimpse into the Future of 3D Game Graphics |accessdate=September 23, 2006 |last=Necasek |first=Michal |date=October 30, 2006}}</ref> |

The faster graphics accelerators and improving [[Central processing unit|CPU]] technology resulted in increasing levels of realism in computer games. During this time, the improvements introduced with products such as ATI's [[Radeon R300]] and [[NVidia]]'s [[GeForce 6 Series]] have allowed developers to increase the complexity of modern [[game engine]]s. PC gaming currently tends strongly toward improvements in 3D graphics.<ref name="graphicstrend">{{cite web|url=http://www.justadventure.com/articles/3D/3DGraphicsTrens.shtm |title=Brief Glimpse into the Future of 3D Game Graphics |accessdate=September 23, 2006 |last=Necasek |first=Michal |date=October 30, 2006}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:34, 15 April 2012

| Video games |

|---|

A PC game, also known as a computer game, is a video game played on a personal computer, rather than on a video game console or arcade machine. PC games have evolved from the simple graphics and gameplay of early titles like Spacewar!, to a wide range of more visually advanced titles.[1]

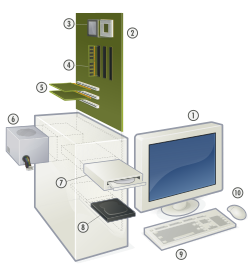

PC games are created by one or more game developers, often in conjunction with other specialists (such as game artists) and either published independently or through a third party publisher. They may then be distributed on physical media such as DVDs and CDs, as Internet-downloadable, possibly freely redistributable, software, or through online delivery services such as Direct2Drive and Steam. PC games often require specialized hardware in the user's computer in order to play, such as a specific generation of graphics processing unit or an Internet connection for online play, although these system requirements vary from game to game.

History

Early growth

Although personal computers only became popular with the development of the microprocessor and microcomputer, computer gaming on mainframes and minicomputers had previously already existed. OXO, an adaptation of tic-tac-toe for the EDSAC, debuted in 1952. Another pioneer computer game was developed in 1961, when MIT students Martin Graetz and Alan Kotok, with MIT student Steve Russell, developed Spacewar! on a PDP-1 mainframe computer used for statistical calculations.[2]

The first generation of computer games were often text adventures or interactive fiction, in which the player communicated with the computer by entering commands through a keyboard. An early text-adventure, Adventure, was developed for the PDP-11 minicomputer by Will Crowther in 1976, and expanded by Don Woods in 1977.[3] By the 1980s, personal computers had become powerful enough to run games like Adventure, but by this time, graphics were beginning to become an important factor in games. Later games combined textual commands with basic graphics, as seen in the SSI Gold Box games such as Pool of Radiance, or Bard's Tale for example.

By the late 1970s to early 1980s, games were developed and distributed through hobbyist groups and gaming magazines, such as Creative Computing and later Computer Gaming World. These publications provided game code that could be typed into a computer and played, encouraging readers to submit their own software to competitions.[4] Microchess was one of the first games for microcomputers which was sold to the public. First sold in 1977, Microchess eventually sold over 50,000 copies on cassette tape.

As with second-generation video game consoles at the time, early home computer games began gaining commercial success by capitalizing on the success of arcade games at the time with ports or clones of popular arcade games.[5][6] By 1982, the top-selling games for the Atari 400 were ports of Frogger and Centipede, while the top-selling game for the Texas Instruments TI-99/4A was the Space Invaders clone TI Invaders.[5] That same year, Pac-Man was ported to the Atari 800,[6] while Donkey Kong was licensed for the Coleco Adam.[7] In late 1981, Atari attempted to take legal action against unauthorized clones, particularly Pac-Man clones, despite some of these predating Atari's exclusive rights to the home versions of Namco's game.[6]

Industry crash

As the video game market became flooded with poor-quality cartridge games created by numerous companies attempting to enter the market, and over-production of high profile releases such as the Atari 2600 adaptations of Pac-Man and E.T. grossly underperformed, the popularity of personal computers for education rose dramatically. In 1983, consumer interest in console video games dwindled to historical lows, as interest in computer games rose.[8] The effects of the crash were largely limited to the console market, as established companies such as Atari posted record losses over subsequent years. Conversely, the home computer market boomed, as sales of low-cost color computers such as the Commodore 64 rose to record highs and developers such as Electronic Arts benefited from increasing interest in the platform.[8]

The console market experienced a resurgence in the United States with the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). In Europe, computer gaming continued to boom for many years after.[8] Computers such as the ZX Spectrum and BBC Micro were successful in the European market, where the NES was not as successful despite its monopoly in Japan and North America. The only 8-bit console to have any success in Europe would be the Sega Master System.[9] Meanwhile in Japan, both consoles and computers became major industries, with the console market dominated by Nintendo and the computer market dominated by NEC's PC-88 (1981) and PC-98 (1982). A key difference between Western and Japanese computers at the time was the display resolution, with Japanese systems using a higher resolution of 640x400 to accommodate Japanese text which in turn had an impact on game design and allowed more detailed graphics. Japanese computers were also using Yamaha's FM synth sound boards from the early 1980s.[10]

New genres

Increasing adoption of the computer mouse, driven partially by the success of games such as the highly successful King's Quest series, and high resolution bitmap displays allowed the industry to include increasingly high-quality graphical interfaces in new releases. Meanwhile, the Commodore Amiga computer achieved great success in the market from its release in 1985, contributing to the rapid adoption of these new interface technologies.[11]

Further improvements to game artwork were made possible with the introduction of FM synthesis sound. Yamaha began manufacturing FM synth boards for computers in the early-mid 1980s, and by 1985, the NEC and FM-7 computers had built-in FM sound.[10] The first sound cards, such as AdLib's Music Synthesizer Card, soon appeared in 1987. These cards allowed IBM PC compatible computers to produce complex sounds using FM synthesis, where they had previously been limited to simple tones and beeps. However, the rise of the Creative Labs Sound Blaster card, released in 1989, which featured much higher sound quality due to the inclusion of a PCM channel and digital signal processor, led AdLib to file for bankruptcy by 1992. Also in 1989, the FM Towns computer included built-in PCM sound, in addition to a CD-ROM drive and 24-bit color graphics.[10]

In 1991, id Software produced an early first-person shooter, Hovertank 3D, which was the company's first in their line of highly influential games in the genre. There were also several other companies that produced early first-person shooters, such as Arsys Software's Star Cruiser,[12] which featured fully 3D polygonal graphics in 1988,[13] and Accolade's Day of the Viper in 1989. Id Software went on to develop Wolfenstein 3D in 1992, which helped to popularize the genre, kick-starting a genre that would become one of the highest-selling in modern times.[14] The game was originally distributed through the shareware distribution model, allowing players to try a limited part of the game for free but requiring payment to play the rest, and represented one of the first uses of texture mapping graphics in a popular game, along with Ultima Underworld.[15]

While leading Sega and Nintendo console systems kept their CPU speed at 3–7 MHz, the 486 PC processor ran much faster, allowing it to perform many more calculations per second. The 1993 release of Doom on the PC was a breakthrough in 3D graphics, and was soon ported to various game consoles in a general shift toward greater realism.[16] In the same time frame, games such as Myst took advantage of the new CD-ROM delivery format to include many more assets (sound, images, video) for a richer game experience.

Many early PC games included extras such as the peril-sensitive sunglasses that shipped with The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. These extras gradually became less common, but many games were still sold in the traditional over-sized boxes that used to hold the extra "feelies". Today, such extras are usually found only in Special Edition versions of games, such as Battlechests from Blizzard.[17]

Contemporary gaming

By 1996, the rise of Microsoft Windows and success of 3D console titles such as Super Mario 64 sparked great interest in hardware accelerated 3D graphics on the IBM PC compatible, and soon resulted in attempts to produce affordable solutions with the ATI Rage, Matrox Mystique and S3 ViRGE. Tomb Raider, which was released in 1996, was one of the first 3D third-person shooter games and was praised for its revolutionary graphics. As 3D graphics libraries such as DirectX and OpenGL matured and knocked proprietary interfaces out of the market, these platforms gained greater acceptance in the market, particularly with their demonstrated benefits in games such as Unreal.[18] However, major changes to the Microsoft Windows operating system, by then the market leader, made many older MS-DOS-based games unplayable on Windows NT, and later, Windows XP (without using an emulator, such as DOSbox).[19][20]

The faster graphics accelerators and improving CPU technology resulted in increasing levels of realism in computer games. During this time, the improvements introduced with products such as ATI's Radeon R300 and NVidia's GeForce 6 Series have allowed developers to increase the complexity of modern game engines. PC gaming currently tends strongly toward improvements in 3D graphics.[21]

Unlike the generally accepted push for improved graphical performance, the use of physics engines in computer games has become a matter of debate since announcement and 2005 release of the nVidia PhysX PPU, ostensibly competing with middleware such as the Havok physics engine. Issues such as difficulty in ensuring consistent experiences for all players,[22] and the uncertain benefit of first generation PhysX cards in games such as Tom Clancy's Ghost Recon Advanced Warfighter and City of Villains, prompted arguments over the value of such technology.[23][24]

Similarly, many game publishers began to experiment with new forms of marketing. Chief among these alternative strategies is episodic gaming, an adaptation of the older concept of expansion packs, in which game content is provided in smaller quantities but for a proportionally lower price. Titles such as Half-Life 2: Episode One took advantage of the idea, with mixed results rising from concerns for the amount of content provided for the price.[25]

Platform characteristics

Openness

The defining characteristic of the PC platform is the absence of centralised control; all other gaming platforms (except Android phones, to an extent) are owned and administered by a single group.

The advantages of openness include:

- Reduced software cost

- Prices are kept down by competition and the absence of platform-holder fees. Games and services are cheaper at every level, and many are free.[26][27]

- Increased flexibility

- PC games decades old can be played on modern systems (through emulation software if need be).[28] Conversely, newer games can often be run on older systems by reducing the games' fidelity and/or scale.

- Increased innovation

- One does not need to ask for permission to release or update a PC game, and the platform's hardware and software are constantly evolving. These two factors make PC the centre of both hardware and software innovation. Closed platforms, by comparison, tend to remain much the same throughout their lifespan.[29]

But there are also disadvantages, including:

- Increased complexity

- A PC is a general-purpose tool. Its inner workings are exposed to the owner and misconfiguration can create enormous problems. Hardware compatibility issues are also possible.

- Increased hardware cost

- PC components are generally sold individually for profit (even if one buys a pre-built machine), whereas the hardware of closed platforms is mass-produced as a single unit and often sold at a loss.[27]

- Games will also use PC hardware less efficiently than that of a closed platform, since the huge variety of possible makes and models prohibits focused optimisation.

- Reduced security

- It is difficult, and in most situations ultimately impossible, to control the way in which PC hardware and software is used. This leads to far more software piracy and cheating than closed platforms suffer from.[30]

Although the PC platform is almost completely decentralised at a hardware level, there are two dominant software forces: the Microsoft Windows operating system and the Steam distribution service. These hold an estimated 95%[31] and 70%[32] of their respective markets.

Fidelity

A PC will generally have far more processing resources at its disposal than other gaming systems.[33] Game developers can use this to improve the visual fidelity of their game relative to other platforms, but even (and in fact particularly) if they do not, games running on PC are likely to benefit from higher screen resolution, higher framerate,[34] and anti-aliasing. Increased draw distance is also common in open world games.[35]

Better hardware also increases the potential fidelity of a PC game's rules and simulation. PC games often support more players or NPCs than equivalents on other platforms[36] and game designs which depend on the simulation of large numbers of tokens (e.g. Total War, Spore, Dwarf Fortress) are rarely seen anywhere else.

The PC also supports greater input fidelity thanks to its compatibility with a wide array of peripherals. The most common forms of input are the mouse/keyboard combination and gamepads, though touchscreens and motion controllers are also available. The mouse in particular lends players of first-person shooter and real-time strategy games on PC great speed and accuracy.

PC game development

Game development, as with all video games, is generally undertaken by one or more game developers using either standardized or proprietary tools. While games could previously be developed by very small groups of people, as in the early example of Wolfenstein 3D, many popular PC games today require large development teams and budgets running into the millions of dollars.[37]

PC games are usually built around a central piece of software, known as a game engine,[38] that simplifies the development process and enables developers to easily port their projects between platforms. Unlike most consoles, which generally only run major engines such as Unreal Engine 3 and RenderWare due to restrictions on open-source software[citation needed], personal computers may run games developed using a larger range of software. As such, a number of alternatives to expensive engines have become available, including open source solutions such as Crystal Space, or OGRE.

User-created modifications

The multi-purpose nature of personal computers often allows users to modify the content of installed games with relative ease. Since console games are generally difficult to modify without a proprietary software development kit, and are often protected by legal and physical barriers against tampering and homebrew software,[39][40] it is generally easier to modify the personal computer version of games using common, easy-to-obtain software. Users can then distribute their customized version of the game (commonly known as a mod) by any means they choose.

The inclusion of map editors such as UnrealEd with the retail versions of many games, and others that have been made available online such as GtkRadiant, allow users to create modifications for games easily, using tools that are maintained by the games' original developers. In addition, companies such as id Software have released the source code to older game engines, enabling the creation of entirely new games and major changes to existing ones.[41]

Modding had allowed much of the community to produce game elements that would not normally be provided by the developer of the game, expanding or modifying normal gameplay to varying degrees. Arguably, the most notable example is Counter-Strike, a mod for Half Life. Counter-Strike turned the initial adventure FPS into a round based, tactical FPS.

Distribution

Physical distribution

PC games are typically sold on standard storage media, such as compact discs, DVD, and floppy disks.[42] These were originally passed on to customers through mail order services,[43] although retail distribution has replaced it as the main distribution channel for video games due to higher sales.[44] Cassette tapes[45] and different formats of floppy disks were initially the staple storage media of the 1980s and early 1990s, but have fallen out of practical use as the increasing sophistication of PC games raised the overall size of the game's data and program files.

The introduction of complex graphics engines in recent times has resulted in additional storage requirements for modern games, and thus an increasing interest in CDs and DVDs as the next compact storage media for PC games. The rising popularity of DVD drives in modern PCs, and the larger capacity of the new media (a single-layer DVD can hold up to 4.7 gigabytes of data, more than five times as much as a single CD), have resulted in their adoption as a format for computer game distribution.

Shareware

Shareware marketing, whereby a limited or demonstration version of the full game is released to prospective buyers without charge, has been used as a method of distributing computer games since the early years of the gaming industry and was seen in the early days of Tanarus as well as many others. Shareware games generally offer only a small part of the gameplay offered in the retail product, and may be distributed with gaming magazines, in retail stores or on developers' websites free of charge.

In the early 1990s, shareware distribution was common among fledging game companies such as Apogee Software, Epic Megagames and id Software, and remains a popular distribution method among smaller game developers. However, shareware has largely fallen out of favor among established game companies in favour of traditional retail marketing, with notable exceptions such as Big Fish Games and PopCap Games continuing to use the model today.[46]

Digital distribution

With the increased popularity of the Internet, online distribution of game content has become more common.[47] Retail services such as Direct2Drive and Download.com allow users to purchase and download large games that would otherwise only be distributed on physical media, such as DVDs, as well as providing cheap distribution of shareware and demonstration games. Companies such as Real Networks provide a service that allows other websites to use their game catalog and ecommerce backend to publish their own game download distribution sites. Other services, allow a subscription-based distribution model in which users pay a monthly fee to download and play as many games as they wish.

The Steam system, developed by Valve Corporation, provides an alternative to traditional online services. Instead of allowing the player to download a game and play it immediately, games are made available for "pre-load" in an encrypted form days or weeks before their actual release date. On the official release date, a relatively small component is made available to unlock the game. Steam also ensures that once bought, a game remains accessible to a customer indefinitely, while traditional mediums such as floppy disks and CD-ROMs are susceptible to unrecoverable damage and misplacement. The user would however depend on the Steam servers to be online to download its games. According to the terms of service for Steam, Valve has no obligation to keep the servers running. Therefore, if the Valve Corporation shut down, so would the servers. However, they have stated that if the service was to be discontinued, games would no longer require authorization from the servers to run. Nevertheless, they are not obligated to do so.

PC game genres

The real-time strategy genre, which accounts for more than a quarter of all PC games sold,[1] has found very little success on video game consoles, with releases such as Starcraft 64 failing in the marketplace. Real-time strategy games tend to suffer from the design of console controllers, which do not allow fast, accurate movement.[48]

PC gaming technology

Hardware

Modern computer games place great demand on the computer's hardware, often requiring a fast central processing unit (CPU) to function properly. CPU manufacturers historically relied mainly on increasing clock rates to improve the performance of their processors, but had begun to move steadily towards multi-core CPUs by 2005. These processors allow the computer to simultaneously process multiple tasks, called threads, allowing the use of more complex graphics, artificial intelligence and in-game physics.[21][49]

Similarly, 3D games often rely on a powerful graphics processing unit (GPU), which accelerates the process of drawing complex scenes in realtime. GPUs may be an integrated part of the computer's motherboard, the most common solution in laptops,[50] or come packaged with a discrete graphics card with a supply of dedicated Video RAM, connected to the motherboard through either an AGP or PCI-Express port. It is also possible to use multiple GPUs in a single computer, using technologies such as NVidia's Scalable Link Interface and ATI's CrossFire.

Sound cards are also available to provide improved audio in computer games. These cards provide improved 3D audio and provide audio enhancement that is generally not available with integrated alternatives, at the cost of marginally lower overall performance.[51] The Creative Labs SoundBlaster line was for many years the de facto standard for sound cards, although its popularity dwindled as PC audio became a commodity on modern motherboards.

Physics processing units (PPUs), such as the Nvidia PhysX (formerly AGEIA PhysX) card, are also available to accelerate physics simulations in modern computer games. PPUs allow the computer to process more complex interactions among objects than is achievable using only the CPU, potentially allowing players a much greater degree of control over the world in games designed to use the card.[50]

Virtually all personal computers use a keyboard and mouse for user input. Other common gaming peripherals are a headset for faster communication in online games, joysticks for flight simulators, steering wheels for driving games and gamepads for console-style games.

Software

Computer games also rely on third-party software such as an operating system (OS), device drivers, libraries and more to run. Today, the vast majority of computer games are designed to run on the Microsoft Windows family of operating systems. Whereas earlier games written for MS-DOS would include code to communicate directly with hardware, today Application programming interfaces (APIs) provide an interface between the game and the OS, simplifying game design. Microsoft's DirectX is an API that is widely used by today's computer games to communicate with sound and graphics hardware. OpenGL is a cross-platform API for graphics rendering that is also used. The version of the graphics card's driver installed can often affect game performance and gameplay. It is not unusual for a game company to use a third-party game engine, or third-party libraries for a game's AI or physics.

Multiplayer

Local area network gaming

Multiplayer gaming was largely limited to local area networks (LANs) before cost-effective broadband Internet access became available, due to their typically higher bandwidth and lower latency than the dial-up services of the time. These advantages allowed more players to join any given computer game, but have persisted today because of the higher latency of most Internet connections and the costs associated with broadband Internet.

LAN gaming typically requires two or more personal computers, a router and sufficient networking cables to connect every computer on the network. Additionally, each computer must have a network card in order to communicate with other computers on the network, and its own copy (or spawn copy) of the game in order to play. Optionally, any LAN may include an external connection to the Internet.

Online games

Online multiplayer games have achieved popularity largely as a result of increasing broadband adoption among consumers. Affordable high-bandwidth Internet connections allow large numbers of players to play together, and thus have found particular use in massively multiplayer online role-playing games, Tanarus and persistent online games such as World War II Online.

Although it is possible to participate in online computer games using dial-up modems, broadband internet connections are generally considered necessary in order to reduce the latency between players (commonly known as "lag"). Such connections require a broadband-compatible modem connected to the personal computer through a network interface card (generally integrated onto the computer's motherboard), optionally separated by a router. Online games require a virtual environment, generally called a "game server". These virtual servers inter-connect gamers, allowing real time, and often fast paced action. To meet this subsequent need, Game Server Providers (GSP) have become increasingly more popular over the last half decade. While not required for all gamers, these servers provide a unique "home", fully customizable (such as additional modifications, settings, etc.) – giving the end gamers the experience they desire. Today there are over 510,000 game servers hosted in North America alone.[52]

Emulation

Emulation software, used to run software without the original hardware, are popular for their ability to play legacy video games without the platform for which they were designed. The operating system emulators include DOSBox, a DOS emulator which allows playing games developed originally for this operating system and thus not compatible with a modern day OS. Console emulators such as NESticle and MAME are relatively commonplace, although the complexity of modern consoles such as the Xbox or PlayStation makes them far more difficult to emulate, even for the original manufacturers.[53]

Most emulation software mimics a particular hardware architecture, often to an extremely high degree of accuracy. This is particularly the case with classic home computers such as the Commodore 64, whose software often depends on highly sophisticated low-level programming tricks invented by game programmers and the demoscene.

Controversy

PC games have long been a source of controversy, particularly related to the violence that has become commonly associated with video gaming in general. The debate surrounds the influence of objectionable content on the social development of minors, with organisations such as the American Psychological Association concluding that video game violence increases children's aggression,[54] a concern that prompted a further investigation by the Center for Disease Control in September 2006.[55] Industry groups have responded by noting the responsibility of parents in governing their children's activities, while attempts in the United States to control the sale of objectionable games have generally been found unconstitutional.[56]

Video game addiction is another cultural aspect of gaming to draw criticism as it can have a negative influence on health and on social relations. The problem of addiction and its health risks seems to have grown with the rise of Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs).[57] Alongside the social and health problems associated with computer game addiction have grown similar worries about the effect of computer games on education.[58]

Computer games museums

There are several computer games museums around the world. In 2011 one opened in Berlin, a computer game museum that documents computer games from the 1970s until today.

See also

References

- ^ a b "Computer and Video Game Software Sales Reach Record $7.3 Billion in 2004" (Press release). Entertainment Software Association. January 26, 2005. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2006.

- ^ Levy, Steven (1984). Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Anchor Press/Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19195-2.

- ^ Jerz, Dennis (2007). "Somewhere Nearby is Colossal Cave: Examining Will Crowther's Original 'Adventure' in Code and in Kentucky". Digital Humanities Quarterly. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ^ "Computer Gaming World's RobotWar Tournament" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. October 1982. p. 17. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- ^ a b "Cash In On the Video Game Craze", Black Enterprise, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 41–2, December 1982, ISSN 0006-4165, retrieved May 1, 2011

- ^ a b c John Markoff (November 30, 1981), "Atari acts in an attempt to scuttle software pirates", InfoWorld, vol. 3, no. 28, pp. 28–9, ISSN 0199-6649, retrieved May 1, 2011

- ^ Charles W. L. Hill & Gareth R. Jones (2007), Strategic management: an integrated approach (8 ed.), Cengage Learning, ISBN 0618894691

- ^ a b c "Player 3 Stage 6: The Great Videogame Crash". April 7, 1999. Retrieved August 16, 2006.

- ^ Travis Fahs. "IGN Presents the History of SEGA: World War". IGN. p. 3. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c John Szczepaniak. "Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier Retro Japanese Computers". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved March 29, 2011. Reprinted from Retro Gamer, 2009

- ^ "Commodore Amiga 1000 Computer". Retrieved August 16, 2006.

- ^ Template:Allgame

- ^ スタークルーザー (translation), 4Gamer.net

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (February 21, 2006). "Analysts: FPS 'Most Attractive' Genre for Publishers". Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- ^ James, Wagner. "Masters of "Doom"". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ "Console history". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Varney, Allen. "Feelies". Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ Shamma, Tahsin. Review of Unreal, Gamespot.com, June 10, 1998.

- ^ Durham, Jr., Joel (May 14, 2006). "Getting Older Games to Run on Windows XP". Archived from the original on April 20, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- ^ Run Older Programs on Windows XP

- ^ a b Necasek, Michal (October 30, 2006). "Brief Glimpse into the Future of 3D Game Graphics". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (May 14, 2006). "Tim Sweeney ponders the future of physics cards". Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ^ Shrout, Ryan (May 2, 2006). "AGEIA PhysX PPU Videos – Ghost Recon and Cell Factor". Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (September 7, 2006). "PhysX Performance Update: City of Villains". Retrieved September 13, 2006.

- ^ "Half Life 2: Episode One for PC Review". 2006. Retrieved September 2, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sweeny, Tim (2007). "Next-Gen podcast". Next Generation Magazine podcast. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

We've been developing games that are community-based for more than ten years now, ever since the original Unreal and Unreal Tournament. We've had games that have had free online gameplay, free server lists, and in 2003 we shipped a game with in-game voice support, and a lot of features that gamers have now come to expect on the PC platform. A lot of these things are now features that Microsoft is planning to charge for.

- ^ a b Lane, Rick (December 13, 2011). "Is PC Gaming Really More Expensive Than Consoles?". IGN.

- ^ "About Us". Good Old Games. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ Bertz, Matt (March 13, 2010). "Valve and Blizzard Defend PC Platform, Diss Console Flexiblity". GameInformer.

- ^ Ghazi, Koroush (2010). "PC Game Piracy Examined". TweakGuides.com.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Holwerda, Thom (February 25, 2009). "Ballmer: Linux Bigger Competitor than Apple". osnews.com.

- ^ Graft, Kris (November 19, 2009). "Stardock Reveals Impulse, Steam Market Share Estimates". Gamasutra. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ^ "Steam Hardware Survey". Valve Corporation. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Ivan, Tom (June 20, 2011). "Console Battlefield 3 is 720p, 30fps. DICE explains". Computer and Video Games.

- ^ Warner, Mark (November 23, 2011). "Tweaking Skyrim Image Quality". HardOCP.

- ^ "DICE on cutting Battlefield 3 console content: 'We're not evil or stupid'". Computer and Video Games. July 26, 2011.

- ^ Wardell, Brad (April 5, 2006). "Postmortem: Stardock's Galactic Civilizations II: Dread Lords". Retrieved September 13, 2006.

- ^ Simpson, Jake (2002). "Game Engine Anatomy 101, Part I". Retrieved September 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Judge deems PS2 mod chips illegal in UK". 2004. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Xbox 360 designed to be unhackable". 2005. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Quake 3 Source Code Released". August, 2005. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Next Billion Dollar Videogame Opportunity". Archived from the original on October 22, 2006. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ Lombardy, Dana (October 1984). "Inside the Industry" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. p. 6. Retrieved October 15, 2006.

- ^ Lombardy, Dana (October 1982). "Inside the Industry" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. p. 2. Retrieved October 15, 2006.

- ^ Konzack, Lars (2008). "Chapter 32 Video Games in Europe". In Wolf, Mark J. P. (ed.). The video game explosion: a history from PONG to Playstation and beyond. Greenwood Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0313338687.

- ^ Chris Morris (June 18, 2003). "The return of shareware". CNN. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ Brendan Sinclair (June 18, 2003). "Spot On: The (new) dawn of digital distribution". Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Joe Fielder (May 12, 2000). "StarCraft 64". Gamespot.com. Retrieved August 19, 2006.

- ^ "Xbox 360 designed to be unhackable". 2005. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Platform Trends: Mobile Graphics Heat Up". 2005. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "X-Fi and the Elite Pro: SoundBlaster's Return to Greatness". 2005. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Steam: Game and Player Statistics

- ^ "Xbox 360 Review". 2005. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ American Psychological Association. "Violent Video Games – Psychologists Help Protect Children from Harmful Effects". Archived from the original on August 3, 2008.

- ^ "Senate bill mandates CDC investigation into video game violence". 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Judge rules against Louisiana video game law". 2006. Retrieved September 2, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Detox For Video Game Addiction?". CBS News. 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Tom Maher discusses the effects of computer game addiction on classroom teaching". dystalk.com. Retrieved April 24, 2009.