Tetragrammaton: Difference between revisions

m r2.6.5) (Robot: Adding ko; removing ta, th; modifying sk |

Wavelength (talk | contribs) →Christian Bible translations into English: adding: * [http://dnkjb.net/ The Divine Name King James Bible] of 2012 uses "Jehovah". |

||

| Line 370: | Line 370: | ||

* The [[American Standard Version]] uses "Jehovah". |

* The [[American Standard Version]] uses "Jehovah". |

||

* The [[New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures|New World Translation]] uses Jehovah over 7,000 times in translations of both the Hebrew and Greek scriptures. |

* The [[New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures|New World Translation]] uses Jehovah over 7,000 times in translations of both the Hebrew and Greek scriptures. |

||

* [http://dnkjb.net/ The Divine Name King James Bible] of 2012 uses "Jehovah". |

|||

==Tetragrammaton in the New Testament== |

==Tetragrammaton in the New Testament== |

||

Revision as of 20:06, 1 July 2012

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (September 2011) |

The term tetragrammaton (from Greek τετραγράμματον, meaning "[a word] having four letters")[1] refers to the Hebrew written form of YHWH (Hebrew: יהוה), one of the names of the God of Israel which is used in the Hebrew Bible and elsewhere.

This written Hebrew name is generally regarded as having been pronounced as Yahweh by modern scholars, though many variant pronunciations have been proposed.

At some point a taboo on saying the name aloud developed in Judaism, and rather than pronounce the written name, other titles were substituted, including "Lord" (in Hebrew Adonai, in Greek Kyrios).[citation needed]

Primary evidence: occurrences in texts

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

Hebrew Bible

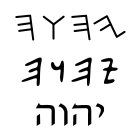

The tetragrammaton occurs 6,828 times in the Hebrew text of both the Biblia Hebraica and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia.[2] The only books it does not appear in are the Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and Esther. It first appears in the Hebrew text in Genesis 2:4.[2][3] The letters, properly read from right to left (in Biblical Hebrew), are:

Hebrew Letter name Pronunciation י Yodh "Y" ה He "H" ו Waw "W", or placeholder for "O"/"U" vowel (see mater lectionis) ה He "H" (or often a silent letter at the end of a word)

Frequency of use in scripture

According to the Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon, יְהֹוָה (Qr אֲדֹנָי) occurs 6,518 times, and יֱהֹוִה (Qr אֱלֹהִים) occurs 305 times in the Masoretic Text.

It appears 6,823 times in the Jewish Bible, according to the Jewish Encyclopedia, and 6,828 times each in the Biblia Hebraica and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia texts of the Hebrew Scriptures. This number in itself is quite remarkable considering the name compared with titles given to God, namely: God (2,605), Almighty (48), Lord (40), Maker (25), Creator (7), Father (7), Ancient of Days (3) and Grand Instructor (2).[4]

Dead Sea scrolls Hebrew and Aramaic texts

These scrolls are unvocalized. Many of these scrolls write (only) the tetragrammaton in paleo-Hebrew script, showing that the name was treated specially.[5]

Representation in Hellenistic Jewish texts

The majority of surviving Jewish Greek texts of the Second Temple period use Greek Kyrios for Hebrew YHWH - this is the standard form found in the corpus of Philo of Alexandria for example. The exceptions are found in a small number of very early surviving manuscripts of the Septuagint where Hebrew letters YHWH are retained among Greek text. The consensus among scholars is that just as the tetragrammaton was pronounced Adonai ("Lord") when reading the Hebrew text, so the embedded YHWH in Greek text was read Kurios, as recorded in the New Testament when Jesus reads from Isaiah in the synagogue at Nazareth.

Septuagint study does give some credence to the possibility that the Divine Name appeared in its original texts. Dr Sidney Jellicoe concluded that "Kahle is right in holding that LXX [= Septuagint] texts, written by Jews for Jews, retained the Divine Name in Hebrew Letters (palaeo-Hebrew or Aramaic) or in the Greek-letters imitative form ΠΙΠΙ, and that its replacement by Κύριος was a Christian innovation".[6] Jellicoe draws together evidence from a great many scholars (B. J. Roberts, Baudissin, Kahle and C. H. Roberts) and various segments of the Septuagint to draw the conclusions that: a) the absence of "Adonai" from the text suggests that the insertion of the term "Kyrios" was a later practice; b) in the Septuagint "Kyrios", or in English "Lord", is used to substitute the Name YHWH; and c) the Tetragrammaton appeared in the original text, but Christian copyists removed it. There is therefore a strong possibility that the Sacred Name was once integrated within the Greek text, but eventually disappeared.

Meyer suggests as one possibility that "as modern Hebrew letters were introduced, the next step was to follow modern Jews and insert 'Kyrios', Lord. This would prove this innovation was of a late date."

Bible scholars and translators as Eusebius and Jerome (translator of the Latin Vulgate) used the Hexapla. Both attest to the importance of the sacred Name and that some manuscripts of Septuagint contained the Tetragrammaton in Hebrew letters.[7] This is further affirmed by The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, which states "Recently discovered texts doubt the idea that the translators of the LXX (Septuagint) have rendered the Tetragrammaton JHWH with KYRIOS. The most ancient mss (manuscripts) of the LXX today available have the Tetragrammaton written in Hebrew letters in the Greek text. This was custom preserved by the later Hebrew translator of the Old Testament in the first centuries (after Christ)"[8]

Later translations into European languages which descended from the Septuagint tended to follow the Greek and use each language's word for "lord": Latin Dominus, German der Herr, English the Lord, French le Seigneur, etc.

These four letters are usually transliterated from Hebrew as IHVH in Latin, JHWH in German, French and Dutch, and JHVH/YHWH in English. This has been variously rendered as "Yahweh" or as "Jehovah", based on the Latin form of the term,[9] while the Hebrew text does not clearly indicate the omitted vowels.

In English translations, the tetragrammaton is often rendered in capital and small capital letters as "the LORD", following Jewish tradition which reads the word as "Adonai" ("Lord") out of respect for the name of God and the interpretation of the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The word "haŠem", "the Name", is also used in Jewish contexts; in Samaritan, "Šemå" is the normal substitution.

In the Kabbalah and Chassidut

As explained by the Ramchal,[10] the Tetragrammaton "unfolds" in accordance with the intrinsic nature of its letters, "in the same order in which they appear in the Name, in the mystery of ten and the mystery of four." Namely, the upper cusp of the Yod is Arich Anpin and the main body of Yod is and Abba; the first Hei is Imma; the Vav is Ze`ir Anpin and the second Hei is Nukvah. It unfolds in this aforementioned order and "in the mystery of the four expansions" that are constituted by the following various spellings of the letters:

ע"ב/`AV : יו”ד ה”י וי”ו ה”י, so called "`AV" according to its gematria value ע"ב=70+2=72.

ס"ג/SaG: יו”ד ה”י וא”ו ה”י, gematria 63.

מ"ה/MaH: יו”ד ה”א וא”ו ה”א, gematria 45.

ב"ן/BaN: יו”ד ה”ה ו”ו ה”ה, gematria 52.

The Ramchal summarizes, "In sum, all that exists is founded on the mystery of this Name and upon the mystery of these letters of which it consists. This means that all the different orders and laws are all drawn after and come under the order of these four letters. This is not one particular pathway but rather the general path, which includes everything that exists in the Sefirot in all their details and which brings everything under its order."[10]

Another parallel is drawn between the four letters of the Tetragrammaton and the Four Worlds: the י is associated with Atziluth, the first ה with Beri'ah, the ו with Yetzirah, and final ה with Assiah.

Magical papyri

The spellings of the tetragrammaton occur among the many combinations and permutations of names of powerful agents that occur in Jewish magical papyri found in Egypt.[11] One of these forms is the heptagram ιαωουηε.[12] In the Jewish magical papyri, Iave and Iαβα Yaba occurs frequently.[13]

In an Ethiopic Christian list of magical names of Jesus,[when?] purporting to have been taught by him to his disciples, Yawe is found.[14]

Aramaic papyri

The form Yahu or Yaho is attested not only in composition but also by itself in Aramaic papyri. This is the form reflected as Ἰαω [ˈʝa.o] in Greek magical papyri.[15] ([h] was not represented by a separate letter in Greek.)

In its earlier form this opinion rested chiefly on certain misinterpreted testimonies in Greek authors about a god Ἰαω and was conclusively refuted by Baudissin; recent adherents of the theory build more largely on the occurrence in various parts of this territory of proper names of persons and places which they explain as compounds of Yahu or Yah.[16]

The explanation is in most cases simply an assumption of the point at issue; some of the names have been misread; others are undoubtedly the names of Jews.

There remain, however, some cases in which it is highly probable that names of non-Israelites are really compounded with Yahweh. The most conspicuous of these is the king of Hamath who in the inscriptions of Sargon (722-705 BCE) is called Yaubi'di and Ilubi'di (compare Jehoiakim-Eliakim). In inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III (745-728 BCE), Azriyau, who was formerly thought to be Uzziah of Judah and/or king of Sam'al, was king of an unknown city-state in northern Syria, probably Hatarikka-Luhuti.[17]

A deity named YW is mentioned in an Ugaritic text as one of the many sons of El. KTU 1.1 IV 14 says:

- sm . bny . yw . ilt

"The name of the son of god, YW".[18][19] That this is a reference to Yahweh, however, has not been widely accepted among scholars, especially since yhwh is entirely absent in all other Ugaritic texts, that the longer form yhwh is likely earlier than the abbreviated yw, and since it is much more probable that the deity referred to in KTU 1.1 IV: 14 is the Ugaritic god Yammu.[20]

Mesopotamian texts

Despite the expectations of earlier years no direct evidence of the name "Yahweh", the tetragrammaton, in Canaanite texts has yet been found.[21]

20th-century scholarship

Friedrich Delitzsch (1902) brought into notice three tablets, of the age of the first dynasty of Babylon, in which he read the names of men called Ya-a'-ve-ilu, Ya-ve-ilu, and Ya-u-um-ilu (meaning "Yahweh is God"), and which he regarded as conclusive proof that Yahweh was known in Babylonia before 2000 BCE; he was a god of the Semitic invaders in the second wave of migration, who were, according to Winckler and Delitzsch, of North Semitic stock (Canaanites, in the linguistic sense).[22]

In 1910 the Encyclopædia Britannica stated that we should thus have in the tablets evidence of the worship of Yahweh among the Western Semites at a time long before the rise of Israel. The reading of the names is, however, extremely uncertain, not to say improbable, and the far-reaching inferences drawn from them carry no conviction.[23]

In 1903 Ernst Sellin excavated at Ta'annuk (the city Taanach of the Book of Joshua) a tablet attributed to the 14th century BCE, in which a man is mentioned whose name may be read Ahi-Yawi, equivalent to the Hebrew name Ahijah.[24] If the reading be correct, this would suggest that Yahweh was worshipped in central Canaan before the Israelite conquest.[25] Genesis 14:17 describes a meeting between Melchizedek the king/priest of Salem and Abraham. Both these pre-conquest figures are described as worshipping the same "Most High God" later identified as Yahweh.

The reading is, however, only one of several possibilities. The fact that the full form Yahweh appears, whereas in Hebrew proper names only the shorter Yahu and Yah occur, weighs somewhat against the interpretation, as it does against Delitzsch's reading of his tablets.

Many attempts have been made to trace the Northwest Semitic Yahu back to Babylonia. Thus Delitzsch (1881) formerly derived the name from an Akkadian god, I or Ia; or from the Semitic nominative ending, Yau;[26]

This deity, Delitzsch's Yahu, has since disappeared from the pantheon of Assyriologists. Jean Bottéro (2000) speculates that the West Semitic Yah/Ia, in fact is a version of the Babylonian god Ea (Enki), a view given support by the earliest finding of this name at Ebla during the reign of Ebrum, at which time the city was under Mesopotamian hegemony of Sargon of Akkad.[27]

Etymology and meaning of YHWH

It has most often been proposed that the name YHWH is a verb form derived from the Biblical Hebrew triconsonantal root היה (h-y-h) "to be", which has הוה (h-w-h) as a variant form, with a third person masculine y- prefix.[28] This would connect it to the passage in verse Exodus 3:14, where God gives his name as אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה (Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh), translated most basically as "I am that I am" (or "I will be that which I now am"). יהוה with the vocalization "Yahweh" could theoretically be a hif'il (causative) verb inflection of root HWH, with a meaning something like "he who causes to exist" or "who gives life" (the root idea of the word perhaps being "to breathe", and hence, "to live").[29] As a qal (basic stem) verb inflection, it could mean "he who is, who exists".[28]

Pronunciation: the question of which vowels

The authentic, historically correct pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton is not known, and the consensus view at various points in history has not been consistent. The current scholarly consensus is that the vowel diacritic points attached to the written consonants YHWH in the Masoretic orthography of Biblical Hebrew were not intended to represent the vowels of such an authentic and historically correct pronunciation, but this was not always understood by Christian Hebrew scholars.

Theophoric names

Yeho or "Yehō-" is the prefix form of "YHWH" used in Hebrew theophoric names; the suffix form Yahū" or "-Yehū" is just as common. This has caused two opinions:

- In former times (at least from c.1650 CE), the prefix pronunciation "Yehō-" was sometimes connected with the full pronunciation "Yehova" derived from combining the Masoretic vowel points for "Adonai" with the consonantal Tetragrammaton YHWH.

- Recently that, as "Yahweh" is likely an imperfective verb form, "Yahu" is its corresponding preterite or jussive short form: compare yiŝtahaweh (imperfective), yiŝtáhû (preterit or jussive short form) = "do obeisance".[30]

Those who argue for argument 1 above are: George Wesley Buchanan in Biblical Archaeology Review; Smith’s 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible;[31] Section # 2.1 The Analytical Hebrew & Chaldee Lexicon (1848)[32] in its article הוה.

Smith's 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible says that "Yahweh" is possible because shortening to "Yahw" would end up as "Yahu" or similar. The Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901–1906 in the Article:Names Of God[33] has a very similar discussion, and also gives the form Yo (יוֹ) contracted from Yeho (יְהוֹ). The Encyclopædia Britannica[34] also says that "Yeho-" or "Yo" can be explained from "Yahweh", and that the suffix "-yah" can be explained from "Yahweh" better than from "Yehovah".

Chapter 1 of The Tetragrammaton and the Christian Greek Scriptures,[35] under the heading The Pronunciation Of God's Name quotes from Insight on the Scriptures, Volume 2, page 7:

- Hebrew Scholars generally favor "Yahweh" as the most likely pronunciation. They point out that the abbreviated form of the name is Yah (Jah in the Latinized form), as at Psalm 89:8 and in the expression Hallelu-Yah (meaning "Praise Yah!" imp. pl.).Ps. 104:35 150:1,6 The forms Yeho', Yo, Yah, and Ya'hu, found in the Hebrew spelling of the names of Yehoshaphat, Yoshaphat, Shefatyah, and others, could be derived from Yahweh... Still, there is by no means unanimity among scholars on the subject, some favoring yet other pronunciations, such as "Yahuwa," "Yahuah," or "Yehuah."[citation needed]

Using consonants as semi-vowels (v/w)

In ancient Hebrew, the letter ו, known to modern Hebrew speakers as vav, was a semivowel /w/ (as in English, not as in German) rather than a /v/.[36] The letter is referred to as waw in the academic world. Because the ancient pronunciation differs from the modern pronunciation, it is common today to represent יהוה as YHWH rather than YHVH.

In unpointed Biblical Hebrew, most vowels are not written and the rest are written only ambiguously, as the vowel letters are also used as consonants (similar to the Latin use of V to indicate both U and V). See Matres lectionis for details. For similar reasons, an appearance of the Tetragrammaton in ancient Egyptian records of the 13th century BCE sheds no light on the original pronunciation.[37] Therefore it is, in general, difficult to deduce how a word is pronounced from its spelling only, and the Tetragrammaton is a particular example: two of its letters can serve as vowels, and two are vocalic place-holders, which are not pronounced.

This difficulty occurs somewhat also in Greek when transcribing Hebrew words, because of Greek's lack of a letter for consonant 'y' and (since loss of the digamma) of a letter for "w", forcing the Hebrew consonants yod and waw to be transcribed into Greek as vowels. Also, non-initial 'h' caused difficulty for Greeks and was liable to be omitted; х (chi) was pronounced as 'k' + 'h' (as in modern Hindi "lakh") and could not be used to spell 'h' as in Modern Greek Χάρρι = "Harry", for example.

Yahweh or Jahweh

The Latin pronunciation of the letter I/J as a consonant sound was [j], the 'y' sound of the English word 'you'. This changed in descendent languages into various stronger consonants, including at one point in French [dʒ], the 'j' sound of the word 'juice', and this was the sound the letter came to be used for in English. Thus the English pronunciation of the older form Jehovah has this 'j' sound, following the English pronunciation of its Latin spelling. In order to preserve the Latin (and approximate Hebrew) pronunciation of Jahweh, however, the English spelling was changed to Yahweh.

Examining the vowel points of יְהֹוָה and אֲדֹנָי

In the table below, Yehowah and Adonai are dissected

| Hebrew Word #3068 YEHOVAH יְהֹוָה |

Hebrew Word #136 ADONAY אֲדֹנָי | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template:Hebrew | Yod | Y | Template:Hebrew | Aleph | glottal stop |

| Template:Hebrew | Simple Shewa | E | Template:Hebrew | Hataf Patah | A |

| Template:Hebrew | Heh | H | Template:Hebrew | Daleth | D |

| Template:Hebrew | Holem | O | Template:Hebrew | Holem | O |

| Template:Hebrew | Waw | W | Template:Hebrew | Nun | N |

| Template:Hebrew | Kametz | A | Template:Hebrew | Kametz | A |

| Template:Hebrew | Heh | H | Template:Hebrew | Yod | Y |

Note in the table directly above that the "simple shewa" in Yehowah and the hatef patah in Adonai are not the same vowel. The same information is displayed in the table above and to the right where "YHWH intended to be pronounced as Adonai" and "Adonai, with its slightly different vowel points" are shown to have different vowel points.

Kethib and Qere and Qere perpetuum

The original consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible was provided with vowel marks by the Masoretes to assist reading. In places where the consonants of the text to be read (the Qere) differed from the consonants of the written text (the Kethib), they wrote the Qere in the margin as a note showing what was to be read. In such a case the vowels of the Qere were written on the Kethib. For a few very frequent words the marginal note was omitted: this is called Q're perpetuum.

One of these frequent cases was the Tetragrammaton, which according to later Jewish practices should not be pronounced, but read as "Adonai" ("My Lord [plural of majesty]"), or, if the previous or next word already was "Adonai", or "Adoni" ("My Lord"), as "Elohim" ("God"). This combination produces יְהֹוָה and יֱהֹוִה respectively, non-words that would spell "yehovah" and "yehovih" respectively.

The oldest manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible, such as the Aleppo Codex and the Codex Leningradensis mostly write Template:Hebrew (yehvah), with no pointing on the first H; this could be because the o diacritic point plays no useful role in distinguishing between Adonai and Elohim (and so is redundant), or could point to the Qere being 'Shema', which is Aramaic for "the Name".

Jehovah

Later, Christian Europeans who did not know about the Q're perpetuum custom took these spellings at face value, producing the form "Jehovah" and spelling variants of it. The Catholic Encyclopedia [1913, Vol. VIII, p. 329] states: "Jehovah (Yahweh), the proper name of God in the Old Testament." Had they known about the Q're perpetuum, the term "Jehovah" may have never come into being.[38] For more information, see the page Jehovah. Contemporary scholars recognise Jehovah to be "grammatically impossible" (Jewish Encyclopedia, Vol VII, p. 8).

יַהְוֶה = Yahweh

In the early 19th century Hebrew scholars were still critiquing "Jehovah" [a.k.a. Iehovah and Iehouah] because they believed that the vowel points of יְהֹוָה did not represent (and were never intended to represent) the vowel sounds of the early authentic pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton. The Hebrew scholar Wilhelm Gesenius [1786–1842] had suggested that the Hebrew punctuation יַהְוֶה, which is transliterated into English as "Yahweh", might more accurately represent the actual pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton than the Biblical Hebrew punctuation "יְהֹוָה", from which the English name Jehovah has been derived.

His proposal to read YHWH as "Template:Hebrew" (see image to the right) was based in large part on various Greek transcriptions, such as ιαβε, dating from the first centuries CE, but also on the forms of theophoric names. In his Hebrew Dictionary, Gesenius supports "Yahweh" (which would have been pronounced [jahwe], with the final letter being silent) because of the Samaritan pronunciation Ιαβε reported by Theodoret, and that the theophoric name prefixes YHW [jeho] and YH [jo] can be explained from the form "Yahweh". Today many scholars accept Gesenius's proposal to read YHWH as Template:Hebrew. Gesenius' proposal gradually became accepted as the best scholarly reconstructed vocalized Hebrew spelling of the Tetragrammaton.

Delitzsch prefers "Template:Hebrew" (yahavah) since he considered the shewa quiescens below ה ungrammatical. In his 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible", William Smith prefers the form "Template:Hebrew" (yahaveh). Many other variations have been proposed.

The Leningrad Codex of 1008–1010

Vowel points were added to the Tetragrammaton by the Masoretes, in the first millennium.

Six Hebrew spellings of the Tetragrammaton are found in the Leningrad Codex of 1008–1010, as shown below. The entries in the Close Transcription column are not intended to indicate how the name was intended to be pronounced by the Masoretes, but only how the word would be pronounced if read without q're perpetuum.

| Chapter & Verse | Hebrew Spelling | Close transcription | Ref. | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This is the most common set of vowels, which are essentially the vowels from Adonai (with the hataf patah reverting to its natural state as a shewa). | ||||

| This is the same as above, but with the dot over the holam/waw left out, because it is a little redundant. | ||||

| When the Tetragrammaton is preceded by Adonai, it receives the vowels from the name Elohim instead. The hataf segol does not revert to a shewa because doing so could lead to confusion with the vowels in Adonai. | ||||

| Just as above, this uses the vowels from Elohim, but like the second version, the dot over the holam/waw is omitted as redundant. | ||||

| Here, the dot over the holam/waw is present, but the hataf segol does get reverted to a shewa. | ||||

| Here, the dot over the holam/waw is omitted, and the hataf segol gets reverted to a shewa. |

ĕ is hataf segol; ǝ is the pronounced form of plain shewa.

The o diacritic dot over the letter waw is often omitted because it plays no useful role in distinguishing between the two intended pronunciations Adonai and Elohim (which both happen to have an o vowel in the same position).

Gérard Gertoux wrote that in the Leningrad Codex, the Masoretes used 7 different vowel pointings [i.e., 7 different Q're's] for YHWH. [Note that one of these different vowel pointings is not a true variant, but was the result of the addition of an inseparable preposition to YHWH][45] A version of the BHS text, which is derived from the Leningrad Codex, is used to translate the Old Testament of almost all English Bibles other than the King James Bible. The Brown–Driver–Briggs Lexicon of 1905 shows only two different vowel pointings [ i.e. variants ] of YHWH are found in the Ben Chayyim Hebrew Text of 1525, which underlies the Old Testament of the King James Bible.[46]

The vocalizations of יְהֹוָה and אֲדֹנָי are not identical

The schwa in YHWH (the vowel under the first letter, ְ) and the hataf patakh in 'DNY (the vowel under its first letter, ֲ), appear different. One reason suggested[who?] is that the spelling יֲהֹוָה (with the hataf patakh) risks that a reader might start pronouncing "Yah", which is a form of the Name, thus completing the first half of the full Name.[citation needed] Alternatively, the vocalization can be attributed to Biblical Hebrew phonology,[47] where the hataf patakh is grammatically identical to a schwa, always replacing every schwa naḥ under a guttural letter. Since the first letter of אֲדֹנָי is a guttural letter, while the first letter of יְהֹוָה is not, the hataf patakh under the (guttural) aleph reverts to a regular schwa under the (non-guttural) yodh.

Josephus's description of vowels

Josephus in Jewish Wars, chapter V, verse 235, wrote "τὰ ἱερὰ γράμματα*ταῦτα δ' ἐστὶ φωνήεντα τέσσαρα" ("...[engraved with] the holy letters; and they are four vowels"), presumably because Hebrew yod and waw, even if consonantal, would have to be transcribed into the Greek of the time as vowels.

Conclusions

Various people draw various conclusions from this Greek material.

William Smith writes in his 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible[48] about the different Hebrew forms supported by these Greek forms:

... The votes of others are divided between Template:Hebrew (yahveh) or Template:Hebrew (yahaveh), supposed to be represented by the Ιαβέ of Epiphanius mentioned above, and Template:Hebrew (yahvah) or Template:Hebrew (yahavah), which Fürst holds to be the Ιευώ of Porphyry, or the Ιαού of Clemens Alexandrinus.

Usage - conventions and prohibitions on speaking the name

Speaking the name in ancient Israel

Exod. 3:15 is used to support the view that the Tetragrammaton was at one time spoken in the way that it is written: "...this is My name for ever, and this is My memorial unto all generations."[49] The term "for ever" is le'olam, which in biblical Hebrew means "always, continually".[50][dead link]

Prohibitions on speaking the name in Judaism

Second Temple period

Some time after destruction of Solomon's Temple use of the Name spoken as written ceased, though the knowledge (of how it was pronounced) was perpetuated in the schools of the rabbis.[51] It was certainly known in Babylonia in the latter part of the 4th century.[52] Nor was the knowledge confined to these pious circles; the name continued to be employed by healers, exorcists and magicians, and has been preserved in many places in magical papyri.[citation needed] Philo calls it ineffable, and says that it is lawful for those only whose ears and tongues are purified by wisdom to hear and utter it in a holy place (that is, for priests in the Temple). In another passage, commenting on Lev. xxiv. 15 seq.: "If any one, I do not say should blaspheme against the Lord of men and gods, but should even dare to utter his name unseasonably, let him expect the penalty of death."[53] Josephus declared that the name was unlawful for him to speak.

The exception for the temple liturgy

Rabbinical sources indicate that the name was only pronounced once a year, by the high priest, on the Day of Atonement.[54] Others argue that the name was also pronounced in the liturgy of the Temple in the priestly benediction (Num. vi. 27) after the regular daily sacrifice, while in the synagogues a substitute (probably Adonai) was used.[55] According to the Talmud, in the last generations before the fall of Jerusalem, however, it was pronounced in a low tone so that the sounds were lost in the chant of the priests.[56]

Mishna and Talmud

The vehemence with which the utterance of the name is denounced in the Mishna suggests that use of Yahweh was unacceptable in rabbinical Judaism.

"He who pronounces the Name with its own letters has no part in the world to come!"[57]

Such is the prohibition of pronouncing the Name as written that it is sometimes called the "Ineffable", "Unutterable" or "Distinctive Name".[58][59][60]

Halakha (Jewish Law) prescribes that whereas the Name written yud-hei-vav-hei, it is only to be pronounced "Adonai;" and the latter name too is regarded as a holy name, and is only to be pronounced in prayer.[61][62] Thus when someone wants to refer in third person to either the written or spoken Name, the handle "ha-Shem" ("the Name") is used;[25][63] and this handle itself can also be used in prayer.[64] Maimonides relates that only the priests in Temple in Jerusalem pronounced the Tetragrammaton, when they recited the Priestly Blessing over the people daily.[65] Since the destruction of Second Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE, the Tetragrammaton is no longer pronounced.

The Masoretes added vowel points (niqqud) and cantillation marks to the manuscripts to indicate vowel usage and for use in the ritual chanting of readings from the Bible in synagogue services. To יהוה they added the vowels for "Adonai" ("My Lord"), the word to use when the text was read.

Tosefta Yadayim records the complaint of the "Morning Bathers" who say, "We have a complaint against you, Pharisees, that you pronounce the divine name in the morning without immersion." (Tosephta Yadayim 2:20).[66]

Kabbala

Kabbalistic tradition holds that the correct pronunciation is known to a select few people in each generation, it is not generally known what this pronunciation is. In late kabbalistic works the Tetragrammaton is sometimes referred to as the name of Havayah—הוי'ה, meaning "the Name of Being/Existence." This name also helps when one needs to refer specifically to the written Name; similarly, "Shem Adonoot," meaning "the Name of Lordship" can be used to refer to the spoken name "Adonai" specifically.

Reasons for the prohibition on speaking the name

Various motives may have concurred to bring about the suppression of the name:

- An instinctive feeling that a proper name for God implicitly recognizes the existence of other gods may have had some influence; reverence and the fear lest the holy name should be profaned among the heathen.

- Desire to prevent abuse of the name in magic. If so, the secrecy had the opposite effect; the name of the God of the Jews was one of the great names, in magic, heathen as well as Jewish, and miraculous efficacy was attributed to the mere utterance of it.

- Avoiding risk of the name being used as an angry expletive, as reported in Leviticus 24:11 in the Bible.

Prohibitions on writing the name

The written Tetragrammaton,[67] as well as six other names of God, must be treated with special sanctity. They cannot be disposed of regularly, lest they be desecrated, but are usually put in long term storage or buried in Jewish cemeteries in order to retire them from use.[68] Similarly, it is prohibited to write the Tetragrammaton (or these other names) unnecessarily. In order to guard the sanctity of the Name sometimes a letter is substituted by a different letter in writing (e.g. יקוק), or the letters are separated by one or more hyphens.

Some Jews are stringent and extend the above safeguard by also not writing out other names of God in other languages, for example writing "God" in English as written "G-d," and so forth. However this is beyond the letter of the law.

Prohibition on speaking the name among the Samaritans

The Samaritans shared the scruples of the Jews about the utterance of the name. However Sanhedrin 10:1 includes the comment of Rabbi Mana "for example those Kutim who take an oath" would also have no share in the world to come, which suggests that Mana thought some Samaritans used the name in making oaths. Though there is no evidence that this was common Samaritan practice.[69][70] (Their priests have preserved a liturgical pronunciation "Yahwe" or "Yahwa" to the present day.)[71] As with Jews, the Aramaic ha-Shema (שמא "the Name") remains the everyday and liturgical usage of the name among Samaritans, akin to Hebrew "the Name" (Hebrew השם "HaShem"). [25]

Speaking the name in Christianity

Christians do not have any taboo on pronouncing the name, either as "Yahweh" or similar variations. Early Jewish Christians inherited from Jews the practice of reading "Lord" where the tetragrammaton appeared in the Hebrew text, or where a tetragrammaton may have been marked in a Greek text. Gentile Christians, primarily non-Hebrew speaking and using Greek texts, read "Lord" as it occurred in the Greek text of the New Testament and their copies of the Greek Old Testament. This practice continued into the Latin Vulgate where "Lord" represented "Yahweh" in the Latin text. Only in the Reformation did the Luther Bible restore "Jehova" in the German text of Luther's Old Testament.[72]

Early Greek and Latin forms

The writings of the Church Fathers contain several references to forms of the Tetragrammaton in Greek or Latin. It should be noted that the Greek form of the divine name, "Iao", is the equivalent of the Hebrew trigrammaton YHW.[73]

The oldest complete Septuagint (Greek Old Testament) versions, from around the 2nd century CE, consistently use Κυριος (= "Lord"), where the Hebrew has YHWH, corresponding to substituting Adonay for YHWH in reading the original; in books written in Greek in this period (e.g., Wisdom, 2 and 3 Maccabees), as in the New Testament, Κυριος takes the place of the name of God. However, older fragments contain the name YHWH.[74] In the P. Ryl. 458 (perhaps the oldest extant Septuagint manuscript) there are blank spaces, leading some scholars to believe that the Tetragrammaton must have been written where these breaks or blank spaces are.[75]

Greek fragment of Leviticus (26:2-16) discovered in the Dead Sea scrolls (Qumran) has ιαω [iao].

Also historian Lydus (6th century) wrote: "The Roman Varo [116–27 BCE] defining him [that is the Jewish god] says that he is called Iao in the Chaldean mysteries" (De Mensibus IV 53).

Van Cooten mentions that Iao is one of the "specifically Jewish designations for God" and "the Aramaic papyri from the Jews at Elephantine show that 'Iao' is an original Jewish term".[76][77]

Patristic writings

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia (1907)[78] and B.D. Eerdmans:[79]

- Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE) writes[80] Ἰαῶ (Iao);

- Irenaeus (d. c. 202) reports[81] that the Gnostics formed a compound Ἰαωθ (Iaoth) with the last syllable of Sabaoth. He also reports[82] that the Valentinian heretics use Ἰαῶ (Iao);

- Clement of Alexandria (d. c. 215)[83] writes Ἰαοὺ (Iaou)—see also below;

- Origen of Alexandria (d. c. 254),[84] Iao;

- Porphyry (d. c. 305) according to Eusebius (d. 339),[85] Ἰευώ (Ieuo);

- Epiphanius (d. 404), who was born in Palestine and spent a considerable part of his life there, gives[86] Ia and Iabe (one codex Iaue);

- (Pseudo-) Jerome (4th/5th century),[87] (tetragrammaton) can be read Iaho;

- Theodoret (d. c. 457) writes Ἰάω (Iao);[88] he also reports[89] that the Samaritans say Ἰαβέ or Ἰαβαί (both pronounced at that time /ja'vε/), while the Jews say Ἀϊά (Aia).[90] (The latter is probably not יהוה but אהיה Ehyeh = "I am " or "I will be", Exod. 3:14 which the Jews counted among the names of God.)

- James of Edessa (d. 708),[91] Jehjeh;

- Jerome (d. 420)[92] speaks of certain Greek writers who misunderstood the Hebrew letters יהוה (read right-to-left) as the Greek letters ΠΙΠΙ (read left-to-right), thus changing YHWH to pipi.

Clement's Stromata

Clement of Alexandria writes in Stromata V, 6:34–35:

- "Πάλιν τὸ παραπέτασμα τῆς εἰς τὰ ἅγια τῶν ἁγίων παρόδου, κίονες τέτταρες αὐτόθι, ἁγίας μήνυμα τετράδος διαθηκῶν παλαιῶν, ἀτὰρ καὶ τὸ τετράγραμμον ὄνομα τὸ μυστικόν, ὃ περιέκειντο οἷς μόνοις τὸ ἄδυτον βάσιμον ἦν· λέγεται δὲ Ἰαού, ὃ μεθερμηνεύεται ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἐσόμενος. Καὶ μὴν καὶ καθʼ Ἕλληνας θεὸς τὸ ὄνομα τετράδα περιέχει γραμμάτων." (Reinhold Koltz text)[93]

The translation[94] of Clement's Stromata in Volume II of the classic Ante-Nicene Fathers series renders this as:

- "... Further, the mystic name of four letters which was affixed to those alone to whom the "adytum" was accessible, is called Jave, which is interpreted, 'Who is and shall be.' The name of God, too [i.e., θεὸς], among the Greeks contains four letters."[95]

Of Clement's Stromata there is only one surviving manuscript, the Codex L (Codex Laurentianus V 3), from the 11th century. Other sources are later copies of that ms. and a few dozen quotations from this work by other authors. For Stromata V,6:34, Codex L has ἰαοὺ. The critical edition by Otto Stählin (1905)[96] gives the forms

- "Ἰαουέ Didymus Taurinensis de pronunc. divini nominis quatuor literarum (Parmae 1799) p. 32ff, ἰαοὺ L, ἰὰ οὐαὶ Nic., ἰὰ οὐὲ Mon. 9.82 Reg. 1888 Taurin. III 50 (bei Did.), ἰαοῦε Coisl. Seg. 308 Reg. 1825."

and has Ἰαουε in the running text. The Additions and Corrections page gives a reference to an author who rejects the change of ἰαοὺ into Ἰαουε.[97]

Other editors give similar data. A catena (Latin: chain) referred to by A. le Boulluec[98] ("Coisl. 113 fol. 368v") and by Smith's 1863 dictionary[99] ("a catena to the Pentateuch in a MS. at Turin") is reported to have "ια ουε".

Christian translations into Greek and Latin

The Septuagint (Greek translation) and Vulgate (Latin translation) use the word "Lord" (κύριος, kyrios, and dominus, respectively).

Christian Bible translations into English

- The New Jerusalem Bible (1966) uses "Yahweh" exclusively.

- The Bible In Basic English (1949/1964) uses "Yahweh" eight times, including Exod. 6:2.

- The New English Bible (NT 1961, OT 1970) generally uses the word "LORD" but uses "JEHOVAH" several times.[100] For examples of both forms, see Exodus Chapter 3 and footnote to verse 15.

- The Amplified Bible (1954/1987). At Exod. 6:3 the AB says "but by My name the Lord [Yahweh--the redemptive name of God] I did not make Myself known to them."

- The Living Bible (1971). "Jehovah" or "Lord".[101]

- The Young's Literal Translation (Version) – "Jehovah" since Genesis 2:4

- The Holman Christian Standard Bible (1999/2002) uses "Yahweh" over 50 times, including Exod. 6:2.

- The World English Bible (WEB) [a Public Domain work with no copyright] uses "Yahweh" some 6837 times.

- The New Living Translation (1996/2004) uses "Yahweh" eight times[verification needed], including Exod. 6:2. The Preface of the New Living Translation: Second Edition says that in a few cases they have used the name Yahweh (for example 3:15; 6:2–3).

- Rotherham's Emphasized Bible retains "Yahweh" throughout the Old Testament.

- The Anchor Bible retains "Yahweh" throughout the Old Testament.

- The King James Version. Rendered in seven instances as "Jehovah", i.e. four times as the name of God, Exod. 6:3; Psalm 83:18; Isa 12:2; 26:4, and three times where it is included in Hebrew place-names e.g. "Jehovah-jireh" -Gen 22:14. (See also Ex 17:15; Judges 6:24)

- Note: Elsewhere in the KJV, "LORD" is generally used. But in verses such as Gen 15:2; 28:13, Psalm 71:5, Amos 1:8, 9:5 etc. where this practice would result in ‘Lord LORD’ (Hebrew: Adonay YHWH) or ‘LORD Lord’ (YHWH Adonay) the KJV translates the Hebrew text as ‘Lord GOD’ or ‘LORD God’.

- The American Standard Version uses "Jehovah".

- The New World Translation uses Jehovah over 7,000 times in translations of both the Hebrew and Greek scriptures.

- The Divine Name King James Bible of 2012 uses "Jehovah".

Tetragrammaton in the New Testament

Since the Tetragrammaton does not appear in the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, virtually all translations refrain from inserting it into the English. The vast majority of New Testament translations therefore render the Greek kyrios as "Lord" or "lord", and theos as "God". Nevertheless, the Sacred Scriptures Bethel Edition inserts the name Yahweh in the New Testament, while the New World Translation inserts the name Jehovah in the New Testament.

Translations of the New Testament into Hebrew

The main notable exception is Delitzsch's translation of the New Testament into Hebrew (1877) which frequently uses the tetragrammaton, i.e. Hebrew (יְהֹוָה), particularly in verses where the New Testament quotes or makes reference to Old Testament texts. It is however still read aloud as "Adonai" by most Hebrew-speaking Christians in Israel.[citation needed]

Use of "Yahweh" or "Lord" in the Catholic Church

In the Catholic Church, the first edition of the official Vatican Nova Vulgata Bibliorum Sacrorum Editio, editio typica, published in 1979, used the traditional Dominus when rendering the Tetragrammaton in the overwhelming majority of places where it appears; however, it also used the form Iahveh for rendering the Tetragrammaton in 3 known places:

In the second edition of the Nova Vulgata Bibliorum Sacrorum Editio, editio typica altera, published in 1986, these few occurrences of the form Iahveh were replaced with Dominus,[105][106][107] in keeping with the long-standing Catholic tradition of avoiding direct usage of the Ineffable Name.

On August 8, 2008, Bishop Arthur J. Serratelli, chairman of the American bishops' "Committee on Divine Worship", announced a new directive from the Vatican regarding the use of the name of God in the sacred liturgy. Specifically, the word "Yahweh" may no longer be "used or pronounced" in songs and prayers during liturgical celebrations.[108] In fact, for most of the Church's 2,000-year history use of the name was prohibited in public worship, out of respect for the Divine Name, according to Catholic tradition. After Second Vatican Council (1962–65), some songs and hymns had begun to use the Tetragrammaton, which caused the Vatican to issue a clarification that the Divine Name was not to be used. Hymnals with these hymns have since inserted the word "Lord God" or other two-syllable alternatives in the place of the Tetragrammaton.

See also

Notes

- ^ It originates from tetra "four" + gramma (gen. grammatos) "letter") "Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ a b "Importance of the Name". Insight on the Scriptures. Vol. vol. 2. Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania. 1988. p. 8.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ The Bible translator. Vol. vol. 56. United Bible Societies. 2005. p. 71.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Nelson's expository dictionary of the Old Testament. Merrill Frederick Unger, William White. 1980. p. 229. - ^ Titles of God

- ^ names of God

- ^ Sidney Jellicoe, Septuagint and Modern Study (Eisenbrauns, 1989, ISBN 0-931464-00-5) pp. 271, 272.

- ^ Papyrus Grecs Bibliques, by Francoise Dunand, Cairo, 1966 pg. 47 ftn. 4

- ^ The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Vol.2, pag.512 Colin Brown 1986

- ^ In the Latin alphabet there was no distinct lettering to distinguish 'Y' ('I') from 'J', or 'W' from 'V'.

- ^ a b In קל"ח פתחי חכמה by Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato, Opening #31; English translation in book "138 Openings of Wisdom" by Rabbi Avraham Greenbaum, 2008, also viewable at http://www.breslev.co.il/articles/spirituality_and_faith/kabbalah_and_mysticism/the_name_of_havayah.aspx?id=10847&language=english, accessed 12. March, 2012

- ^ B. Alfrink, La prononciation 'Jehova' du tétragramme, O.T.S. V (1948) 43-62.

- ^ K. Preisendanz, Papyri Graecae Magicae, Leipzig-Berlin, I, 1928 and II, 1931.

- ^ Footnote #9 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See Deissmann, Bibelstudien, 13 sqq."

- ^ Footnote #10 from Page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See Driver, Studia Biblica, I. 20." Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition (New York: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1910–11), vol. 15, pp. 312, in the article "JEHOVAH".

- ^ Aramaic Papyri discovered at Assaan, B 4,6,II; E 14; J 6; "This doubtless is the original of Ἰαω frequently found in Greek authors and in magical texts as the name of the God of the Jews." (EB 1911)

- ^ Footnote #4 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See a collection and critical estimate of this evidence by Zimmern, Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament, 465 sqq."

- ^ J.D. Hawkins: Izrijau, in Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie vol. 5, p. 227. Berlin; New York: de Gruyter 1976–1980.

- ^ Ugarit and the Bible, site of Quartz Hill School of Theology.

- ^ Smith, Mark S. (2001) The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-516768-6).

- ^ van der Toorn (1995), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible," 911 ISBN 0-8028-2491-9;

- Mark S. Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle, Volume 1: Introduction with Text, Translation and Commentary of KTU 1.1-1.2 (VTSup 55; Leiden: Brill, 1994), 151-52;

- D. N. Freedman and Michael O'Connor, TDOT 5:510;

- Marvin H. Pope, Syrien: Die Mythologie der Ugariter und Phonizier," in Gotter und Mythen im vorderen Orient (vol. 1, part 1 of Worterbuch Der Mythologie; ed. H. W. Haussig; Suttgart: Ernst Klett Verlag, 1965), 291-92.

- ^ Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible DDD K. van der Toorn (1995), Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst, 1999:960 "In no list of gods or offerings is the mysterious god *Ya ever mentioned; his cult at Ebla is a chimera. Yahweh was not known at Ugarit either; the singular name Yw (vocalisation unknown) in a damaged passage of the Baal Cycle (KTU 1.1 " ISBN 0-8028-2491-9

- ^ Footnote #5 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Babel und Bibel, 1902. The enormous, and for the most part ephemeral, literature provoked by Delitzsch's lecture cannot be cited here.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition (New York: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1910–11), vol. 15, pp. 312, in the Article "JEHOVAH".

- ^ Footnote #6 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Denkschriften d. Wien. Akad., L. iv. p. 115 seq. (1904)."

- ^ a b c Stanley S. Seidner,"HaShem: Uses through the Ages." Unpublished paper, Rabbinical Society Seminar, Los Angeles, CA,1987.

- ^ Footnote #7 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Wo lag das Paradies? (1881), pp. 158–166."

- ^ Jean Bottéro Antiqities assyro-babyloniennes (L'Epopee d'Ena) Annuaire EPHE (1977–78) 160.

- ^ a b The New Brown–Driver–Briggs-Gesenius Hebrew and English Lexicon With an Appendix Containing the Biblical Aramaic by Frances Brown, with the cooperation of S.R. Driver and Charles Briggs (1907), p. 217ff (entry יהוה listed under root הוה).

- ^ "Names Of God". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ "AnsonLetter.htm". Members.fortunecity.com. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ Smith’s 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible

- ^ The Analytical Hebrew & Chaldee Lexicon by Benjamin Davidson ISBN 0-913573-03-5.

- ^ The Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901–1906 Names Of God

- ^ "Jehovhah." Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition (New York: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1910–11, vol. 15, 312 pp.

- ^ [1]

- ^ (see any Hebrew grammar).

- ^ See pages 128 and 236 of the book "Who Were the Early Israelites?" by archeologist William G. Dever, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2003.

- ^ "Job – Introduction, Anchor Bible, volume 15, page XIV and "Jehovah" Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th Edition, volume 15.

- ^ "Unicode/XML Leningrad Codex". Tanach.us. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Unicode/XML Leningrad Codex". Tanach.us. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Unicode/XML Leningrad Codex". Tanach.us. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Unicode/XML Leningrad Codex". Tanach.us. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Unicode/XML Leningrad Codex". Tanach.us. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Unicode/XML Leningrad Codex". Tanach.us. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ refer to the table on page 144 of Gérard Gertoux's book The Name of God Y.EH.OW.Ah which is pronounced as it is written I_EH_OU_AH.

- ^ "villagephotos.com".

- ^ Lambdin, Thomas O.: Introduction to Biblical Hebrew, London: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971.

- ^ "A Dictionary of the Bible"

- ^ "3:15 And God said moreover unto Moses: 'Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel: The LORD, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, hath sent me unto you; this is My name for ever, and this is My memorial unto all generations." mechon-mamre.org Retrieved 7 October 2010

- ^ "Morphix Dictionary".[dead link]

- ^ Footnote #1 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:"R. Johannan (second half of the 3rd century), Kiddushin, 71a."

- ^ Footnote #2 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:"Kiddushin, l.c. = Pesahim, 50a".

- ^ Footnote #3 from page 311 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See Josephus, Ant. ii. 12, 4; Philo, Vita Mosis, iii. II (ii. 114, ed. Cohn and Wendland); ib. iii. 27 (ii. 206). The Palestinian authorities more correctly interpreted Lev. xxiv. 15 seq., not of the mere utterance of the name, but of the use of the name of God in blaspheming God."

- ^ The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period p 779 William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz - 2006 "(BT Kidd 7ia) The historical picture described above is probably wrong because the Divine Names were a priestly ... Name was one of the climaxes of the Sacred Service: it was entrusted exclusively to the High Priest once a year on the "

- ^ Footnote #4 from page 311 of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica: "Siphre, Num. f 39, 43; M. Sotak, iii. 7; Sotah, 38a. The tradition that the utterance of the name in the daily benedictions ceased with the death of Simeon the Just, two centuries or more before the Christian era, perhaps arose from a misunderstanding of Menahoth, 109b; in any case it cannot stand against the testimony of older and more authoritative texts."

- ^ Yoma, 39b; Jer. Yoma,iii. 7; Kiddushin, 71a." (cited after EB 1911)

- ^ Footnote #3 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "M. Sanhedrin, x.I; Abba Saul, end of 2nd century."

- ^ "Judaism 101 on the Name of God". jewfaq.org.

- ^ For example, see Saul Weiss and Joseph Dov Soloveitchik (2005-02). Insights of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7425-4469-7.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) and Minna Rozen (1992). Jewish Identity and Society in the 17th century. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-16-145770-8. - ^ M. Rösel The reading and translation of the divine name in the masoretic tradition and the Greek Pentateuch - Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 2007 "It is in this book that we find the strictest prohibition against pronouncing the name of the Lord. The Hebrew of 24.16, which may be translated as 'And he that blasphemes/curses (3B?) the name of the Lord (9H9J), he shall surely be put to death', in the LXX is subjected to a ..."

- ^ "They [the Priests, when reciting the Priestly Blessing, when the Temple stood] recite [God's] name -- i.e., the name yod-hei-vav-hei, as it is written. This is what is referred to as the 'explicit name' in all sources. In the country [that is, outside the Temple], it is read [using another one of God's names], א-ד-נ-י ('Adonai'), for only in the Temple is this name [of God] recited as it is written." -- Mishneh Torah Maimonides, Laws of Prayer and Priestly Blessings, 14:10

- ^ Kiddushin 71a states, "I am not referred to as [My name] is written. My name is written yod-hei-vav-hei and it is pronounced "Adonai."

- ^ For example, two common prayer books are titled "Tehillat Hashem" and "Avodat Hashem." Or, a person may tell a friend, "Hashem helped me to perform a great mitzvah today."

- ^ For example, in the common utterance and praise, "Barukh Hashem" (Blessed [i.e. the source of all] is Hashem), or "Hashem yishmor" (God protect [us])

- ^ Mishneh Torah Maimonides, Laws of Prayer and Priestly Blessings, Chapter 14; http://www.chabad.org/dailystudy/rambam.asp?tDate=3/28/2012&rambamChapters=3

- ^ The Dead Sea scrolls: forty years of research Devorah Dimant, Uriel Rappaport, Yad Yitsḥaḳ Ben-Tsevi - 1992 "'The Morning Bathers say, We have a complaint against you, Pharisees, that you pronounce the divine name in the morning without immersion. (Tosephta Yadayim 2,20) It may also be that the Essene sunrise prayer did not ..."

- ^ See Deut. 12:2-4: “You must destroy all the sites at which the nations you are to dispossess worshiped their gods...tear down their altars...and cut down the images of their gods, obliterating their name from that site. Do not do the same thing to Hashem (YHWH) your God.”

- ^ "Based on the Talmud (Shavuot 35a-b), Maimonides (Hilkhot Yesodei HaTorah, Chapter 6), and the Shulchan Arukh (Yoreh Deah 276:9) it is prohibited to erase or obliterate the seven Hebrew names for God found in the Torah (in addition to the above, there is E-l, E-loha, Tzeva-ot, Sha-dai,...).

- ^ The Talmud Yerushalmi and Graeco-Roman culture: Volume 3 - Page 152 Peter Schäfer, Catherine Hezser - 2002 " In fact, there is no proof in any other rabbinic writing that Samaritans used to pronounce the Divine Name when they took an oath. The only evidence for Sarmaritans uttering the Tetragrammaton at that ..."

- ^ Jer. Sanhedrin, x.I; R. Mana, 4th century (cited after EB 1911).

- ^ Montgomery, Journal of Biblical Literature, xxv. (1906), 49-51 (cited after EB 1911)

- ^ A Catholic Handbook: Essentials for the 21st Century Page 51 William C. Graham - 2010 "WHY DO WE NO LONGER SAY YAHWEH? The Vatican's Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments directed in ... just as the Hebrews and early Christians substituted other names for Yahweh when reading Scripture aloud."

- ^ Bezalel Porten, Archives from Elephantine: The life of an ancient Jewish military colony, 1968, University of California Press, pp. 105, 106.

- ^ The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology Volume 2, p. 512.

- ^ Paul Kahle, The Cairo Geniza (Oxford:Basil Blackwell,1959) p. 222.

- ^ Stern M., Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism (1974-84) 1:172; Schafer P., Judeophobia: Attitudes toward the Jews in the Ancient World (1997) 232; Cowley A., Aramaic Papyri of the 5th century (1923); Kraeling E.G., The Brooklyn Museum Aramaic Papyri: New Documents of the 5th century BCE from the Jewish Colony at Elephantine (1953)

- ^ Sufficient examination of the subject is available at Sean McDonough's YHWH at Patmos (1999), pp 116 to 122 and George van Kooten's The Revelation of the Name YHWH to Moses (2006), pp 114, 115, 126-136. It worths to mention a foundamental though aged source about the subject: Adolf Deissmann's Bible studies: Contributions chiefly from papyri and inscriptions to the history of the language, the literature, and the religion of Hellenistic Judaism and primitive Christianity (1909), at chapter "Greek transcriptions of the Tetragrammaton".

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ B.D. Eerdmans, The Name Jahu, O.T.S. V (1948) 1-29.

- ^ "Among the Jews Moses referred his laws to the god who is invoked as Iao (Gr. Ιαώ)." (Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica I, 94:2)

- ^ Irenaeus, "Against Heresies", II, xxxv, 3, in P. G., VII, col. 840.

- ^ Irenaeus, "Against Heresies", I, iv, 1, in P.G., VII, col. 481.

- ^ Clement, "Stromata", V, 6, in P.G., IX, col. 60.

- ^ Origen, "In Joh.", II, 1, in P.G., XIV, col. 105.

- ^ Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica I, ix, in P.G., XXI, col. 72 A; and also ibid. X, ix, in P.G., XXI, col. 808 B.

- ^ Epiphanius, Panarion, I, iii, 40, in P.G., XLI, col. 685.

- ^ "nomen Domini apud Hebraeos quatuor litterarum est, jod, he, vau, he: quod proprie Dei vocabulum sonat: et legi potest JAHO, et Hebraei ἄῤῥητον, id est, ineffabile opinatur." ("Breviarium in Psalmos. Psalm. viii.", in P.L., XXVI, col. 838 A). This work was traditionally attributed to Jerome, but authenticity has been doubted or denied since modern times. But "now believed to be genuine and to be dated before CE 392" ZATW (W. de Gruyter, 1936. page 266)

- ^ "the word Nethinim means in Hebrew 'gift of Iao', that is the God who is" (Theodoret, "Quaest. in I Paral.", cap. ix, in P. G., LXXX, col. 805 C)

- ^ Theodoret, "Ex. quaest.", xv, in P. G., LXXX, col. 244 and "Haeret. Fab.", V, iii, in P. G., LXXXIII, col. 460.

- ^ Footnote #8 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Aïα occurs also in the great magical papyrus of Paris, 1. 3020 (Wessely, Denkschrift. Wien. Akad., Phil. Hist. Kl., XXXVI. p. 120) and in the Leiden Papyrus, Xvii. 31."

- ^ cf. Lamy, "La science catholique", 1891, p. 196.

- ^ Jerome, "Ep. xxv ad Marcell.", in P. L., XXII, col. 429.

- ^ Reinhold Koltz

- ^ "ANF02. Fathers of the 2nd century: Hermas, Tatian, Athenagoras, Theophilus, and Clement of Alexandria, Chapter VI.—The Mystic Meaning of the Tabernacle and its Furniture". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 2010-09-27.]

- ^ The Rev. Alexander Roberts, D.D, and James Donaldson, LL.D. (ed.). "VI. The Mystic Meaning of the Tabernacle and Its Furniture". The Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. II: Fathers of the 2nd century (American reprint of the Edinburgh ed.). p. 452. Retrieved 2006–12–19.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Clemens Alexandrinus Werke, eds. Stählin. O. and Fruechtel. L. (Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller der ersten drei Jahrhunderte, 15), 3. Auflage, Berlin, 1960.

- ^ Richard Ganschinietz, "Iao" in Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft 9.1:700.28.

- ^ Clément d'Alexandrie. Stromate V. Tome I: Introduction, texte critique et index, par A. Le Boulluec, Traduction de † P. Voulet, S.J.; Tome II : Commentaire, bibliographie et index, par A. Le Boulluec, Sources Chrétiennes n° 278 et 279, Editions du Cerf, Paris 1981. (Tome I, pp. 80, 81).

- ^ Smith’s 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible"

- ^ Usage in English

- ^ The Living Bible, "Jehovah" or "Lord" per text or footnotes. e.g. Genesis 7:16; 8:21; Exodus 3:15.

- ^ "Dixítque íterum Deus ad Móysen: «Hæc dices fíliis Israel: Iahveh (Qui est), Deus patrum vestrórum, Deus Abraham, Deus Isaac et Deus Iacob misit me ad vos; hoc nomen mihi est in ætérnum, et hoc memoriále meum in generatiónem et generatiónem." (Exodus 3:15).

- ^ "Dominus quasi vir pugnator; Iahveh nomen eius!" (Exodus 15:3).

- ^ "Aedificavitque Moyses altare et vocavit nomen eius Iahveh Nissi (Dominus vexillum meum)" (Exodus 17:15).

- ^ "Exodus 3:15: Dixítque íterum Deus ad Móysen: «Hæc dices fíliis Israel: Dominus, Deus patrum vestrórum, Deus Abraham, Deus Isaac et Deus Iacob misit me ad vos; hoc nomen mihi est in ætérnum, et hoc memoriále meum in generatiónem et generatiónem."

- ^ "Exodus 15:3: Dominus quasi vir pugnator; Dominus nomen eius!"

- ^ "Exodus 17:15: Aedificavitque Moyses altare et vocavit nomen eius Dominus Nissi (Dominus vexillum meum)"

- ^ "CNS STORY: No 'Yahweh' in songs, prayers at Catholic Masses, Vatican rules". Retrieved 2009–07–29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

External links

Media related to Tetragrammaton at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tetragrammaton at Wikimedia Commons- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|W1EC=ignored (help)