Loving v. Virginia: Difference between revisions

←Replaced content with 'sdsd {{Link GA|de}}' Tag: possible vandalism |

m Reverted edits by 50.202.214.66 (talk) (HG 3) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{SCOTUSCase |

|||

sdsd |

|||

|Litigants=Loving v. Virginia |

|||

|ArgueDate=April 10 |

|||

|ArgueYear=1967 |

|||

|DecideDate=June 12 |

|||

|DecideYear=1967 |

|||

|FullName=Richard Perry Loving, Mildred Jeter Loving v. Virginia |

|||

|Citation=87 S. Ct. 1817; 18 L. Ed. 2d 1010; 1967 U.S. LEXIS 1082 |

|||

|USVol=388 |

|||

|USPage=1 |

|||

|Prior=Defendants convicted, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 6, 1959); motion to vacate judgment denied, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 22, 1959); affirmed in part, reversed and remanded, 147 S.E.2d 78 (Va. 1966) |

|||

|Subsequent= |

|||

|Holding=The Court declared [[Virginia]]'s [[anti-miscegenation statute]], the "[[Racial Integrity Act of 1924]]", unconstitutional, as a violation of the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. |

|||

|OralArgument=http://www.oyez.org/cases/1960-1969/1966/1966_395/argument/ |

|||

|SCOTUS=1965-1967 |

|||

|Majority=Warren |

|||

|JoinMajority=''unanimous'' |

|||

|Concurrence=Stewart |

|||

|LawsApplied=[[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|U.S. Const. amend. XIV]]; Va. Code §§ 20-58, 20-59 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{wikisource}} |

|||

'''''Loving v. Virginia''''', {{ussc|388|1|1967}},<ref>[http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=US&vol=388&invol=1 Full text of the opinion in Loving v. Virginia courtesy of Findlaw.com.]</ref> was a [[Landmark decision|landmark]] [[civil rights]] decision of the [[United States Supreme Court]] which invalidated [[Interracial marriage in the United States|laws prohibiting]] [[interracial marriage]]. |

|||

The case was brought by Mildred Loving, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, who had been sentenced to a year in prison in [[Virginia]] for marrying each other. Their marriage violated the state's [[anti-miscegenation]] statute, the [[Racial Integrity Act of 1924]], which prohibited marriage between people classified as "[[White people|white]]" and people classified as "[[colored]]." The Supreme Court's unanimous decision held this prohibition was unconstitutional, overturning ''[[Pace v. Alabama]]'' (1883) and ending all [[Race (classification of human beings)|race]]-based legal restrictions on [[marriage in the United States]]. |

|||

The decision was followed by an increase in interracial marriages in the U.S., and is remembered annually on [[Loving Day]], June 12. It has been the subject of two movies as well as songs. In the 2010s, it again became relevant in the context of the debate about [[same-sex marriage in the United States]]. |

|||

==Background== |

|||

[[Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States]] had been in place in certain states since before the [[United States Declaration of Independence|United States declared independence]]. |

|||

[[File:US miscegenation.svg|thumb|left|U.S States, by the date of repeal of anti-miscegenation laws: {{legend|#d3d3d3|No laws passed}} |

|||

{{legend|#5b9e39|Before 1887}} |

|||

{{legend|#f3ee66|1948 to 1967}} |

|||

{{legend|#cc2f2f|12 June 1967}}]] |

|||

===Plaintiffs=== |

|||

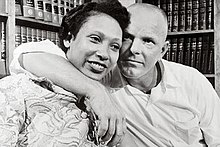

[[Image:Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving.jpg|thumb|left|Mildred and Richard Loving in 1967]] |

|||

The [[plaintiff]]s in the case were Mildred Delores Loving, ''née'' Jeter (July 22, 1939 – May 2, 2008), a woman of [[African-American]] and [[Rappahannock tribe|Rappahannock]] [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American]] descent,<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.charlielawing.com/modhist_lovingv.virginia.pdf | title=''Loving v. Virginia'' and the Hegemony of "Race" | format=PDF | last=Lawing | first=Charles B. | year=2000 | accessdate=2013-05-31}}</ref><ref>[http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-06-10-loving_N.htm Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back]</ref><ref name='SSDI-Mildred'>{{cite web |url=http://www.ancestry.com |title= Social Security Death Index (Mildred D. Loving) [database on-line] |publisher= The Generations Network |location=[[United States]] |accessdate=May 6, 2009}}</ref> and Richard Perry Loving (October 29, 1933 – June 1975),<ref name='SSDI-Richard'>{{cite web |url=http://www.ancestry.com |title= Social Security Death Index (Richard Loving) [database on-line] |publisher= The Generations Network |location=[[United States]] |accessdate=May 6, 2009}}</ref> a white man. |

|||

The couple had three children: Donald, Peggy, and Sidney. Richard Loving died aged 41 in 1975, when a drunk driver struck his car in [[Caroline County, Virginia]].<ref>{{cite news| url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10D13FD3B58157493C3A9178CD85F418785F9 | work=The New York Times | title=RICHARD P. LOVING; IN LAND MARK SUIT; Figure in High Court Ruling on Miscegenation Dies | date=July 1, 1975}}</ref> Mildred Loving lost her right eye in the same accident. She died of [[pneumonia]] on May 2, 2008, in [[Milford, Virginia]], aged 68.<ref name=NYtimes>{{cite news|author=Douglas Martin|title=Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/06/us/06loving.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=Mildred+Loving&st=nyt&oref=slogin|publisher=The New York Times|date=May 6, 2008|quote=Mildred Loving, a black woman whose anger over being banished from Virginia for marrying a white man led to a landmark Supreme Court ruling overturning state miscegenation laws, died on May 2 at her home in Central Point, Va. She was 68.|accessdate=May 7, 2008}}</ref> |

|||

===Criminal proceedings=== |

|||

At the age of 18, Mildred became pregnant, and in June 1958 the couple traveled to [[Washington, D.C.]] to marry, thereby evading Virginia's [[Racial Integrity Act of 1924]], which made interracial marriage a crime. They returned to the small town of [[Central Point, Virginia]]. Based on an anonymous tip,<ref name=NYT>Martin, Douglas. [http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/06/us/06loving.html "Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68"], ''New York Times'', May 6, 2008.</ref> local police raided their home at night, hoping to find them having sex, which was also a crime according to Virginia law. When the officers found the Lovings sleeping in their bed, Mildred pointed out their marriage certificate on the bedroom wall. That certificate became the evidence for the criminal charge of "cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth" that was brought against them. |

|||

The Lovings were charged under Section 20-58 of the Virginia Code, which prohibited interracial couples from being married out of state and then returning to Virginia, and Section 20-59, which classified [[miscegenation]] as a felony, punishable by a prison sentence of between one and five years. The trial judge in the case, [[Leon M. Bazile]], echoing [[Johann Friedrich Blumenbach]]'s 18th-century interpretation of race: |

|||

{{cquote|''Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.''}} |

|||

On January 6, 1959, the Lovings pled guilty and were sentenced to one year in prison, with the sentence suspended for 25 years on condition that the couple leave the state of Virginia. They did so, moving to the [[District of Columbia]]. |

|||

===Appellate proceedings=== |

|||

In 1964,<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/remember/jan-june08/loving_05-06.html "Mildred Loving, Key Figure in Civil Rights Era, Dies"], PBS Online News Hour, May 6, 2008</ref> frustrated by their inability to travel together to visit their families in Virginia and social isolation and financial difficulties in Washington, Mildred Loving wrote in protest to [[United States Attorney General|Attorney General]] [[Robert F. Kennedy]]. Kennedy referred her to the [[American Civil Liberties Union]] (ACLU).<ref name=NYT/> |

|||

The ACLU filed a motion on behalf of the Lovings in the state trial court to [[Vacated judgment|vacate]] the judgment and set aside the sentence on the grounds that the violated statutes ran counter to the [[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fourteenth Amendment]]. This set in motion a series of lawsuits which ultimately reached the Supreme Court. |

|||

On October 28, 1964, after the Lovings' motion still had not been decided, they brought a class action suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. On January 22, 1965, the three-judge district court decided to allow the Lovings to present their constitutional claims to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. Virginia Supreme Court Justice [[Harry L. Carrico]] (later Chief Justice of the Court) wrote an opinion for the court upholding the constitutionality of the anti-miscegenation statutes and, after modifying the sentence, affirmed the criminal convictions. Ignoring United States Supreme Court precedent, Carrico cited as authority the Virginia Supreme Court's own decision in ''[[Naim v. Naim]]'' (1955), also arguing that the case at hand was not a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause because both the white and the non-white spouse were punished equally for the crime of miscegenation, an argument similar to that made by the United States Supreme Court in 1883 in ''[[Pace v. Alabama]]''. |

|||

The Lovings, supported by the ACLU, appealed the decision to the United States Supreme Court. They did not attend the oral arguments in Washington, but their lawyer, [[Bernard S. Cohen]], conveyed the message he had been given by Richard Loving to the court: "Mr. Cohen, tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."<ref>Kate Sheppard, [http://www.motherjones.com/media/2012/02/the-loving-story-documentary-hbo {{"'}}The Loving Story': How an Interracial Couple Changed a Nation"], ''[[Mother Jones (magazine)|Mother Jones]]'', Feb 13, 2012. Also quoted in [http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Loving_v_Virginia_1967 Loving v. Virginia (1967)], ''[[Encyclopedia Virginia]]''</ref> |

|||

==Precedents== |

|||

Before ''Loving v. Virginia'', there had been several cases on the subject of interracial relations. In ''[[Pace v. Alabama]]'' (1883), the Supreme Court ruled that the conviction of an Alabama couple for interracial sex, affirmed on appeal by the Alabama Supreme Court, did not violate the [[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fourteenth Amendment]]. Interracial marital sex was deemed a felony, whereas extramarital sex ("adultery or fornication") was only a misdemeanor. On appeal, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the criminalization of interracial sex was not a violation of the [[equal protection clause]] because whites and non-whites were punished in equal measure for the offense of engaging in interracial sex. The court did not need to affirm the constitutionality of the ban on interracial marriage that was also part of Alabama's anti-miscegenation law, since the plaintiff, Mr. Pace, had chosen not to appeal that section of the law. After ''Pace v. Alabama'', the constitutionality of [[anti-miscegenation laws]] banning marriage and sex between whites and non-whites remained unchallenged until the 1920s. |

|||

In ''Kirby v. Kirby'' (1921), Mr. Kirby asked the state of Arizona for an annulment of his marriage. He charged that his marriage was invalid because his wife was of ‘negro’ descent, thus violating the state's anti-miscegenation law. The Arizona Supreme Court judged Mrs. Kirby’s race by observing her physical characteristics and determined that she was of mixed race, therefore granting Mr. Kirby’s annulment.<ref name=Pascoe_pp49-51>{{harvnb|Pascoe|1996|pp=49–51}}</ref> |

|||

In the ''Monks'' case (''[[Estate of Monks]]'', 4. Civ. 2835, Records of California Court of Appeals, Fourth district), the Superior Court of San Diego County in 1939 decided to invalidate the marriage of Marie Antoinette and Allan Monks because she was deemed to have "one eighth negro blood." The court case involved a legal challenge over the conflicting wills that had been left by the late Allan Monks, an old one in favor of a friend named Ida Lee and a newer one in favor of his wife. Lee's lawyers charged that the marriage of the Monkses, which had taken place in Arizona, was invalid under Arizona state law because Marie Antoinette was "a Negro" and Alan had been white. Despite conflicting testimony by various expert witnesses, the judge defined Mrs. Monks' race by relying on the anatomical "expertise" of a surgeon. The judge ignored the arguments of an anthropologist and a biologist that it was impossible to tell a person's race from physical characteristics.<ref name=Pascoe_p56>{{harvnb|Pascoe |1996|p=56}}</ref> |

|||

Monks then challenged the Arizona anti-miscegenation law itself, taking her case to the California Court of Appeals, Fourth District. Monks' lawyers pointed out that the anti-miscegenation law effectively prohibited Monks as a mixed-race person from marrying anyone: "As such, she is prohibited from marrying a negro or any descendant of a negro, a Mongolian or an Indian, a Malay or a Hindu, or any descendants of any of them. Likewise ... as a descendant of a negro she is prohibited from marrying a Caucasian or a descendant of a Caucasian...." The Arizona anti-miscegenation statute thus prohibited Monks from contracting a valid marriage in Arizona, and was therefore an unconstitutional constraint on her liberty. The court, however, dismissed this argument as inapplicable, because the case presented involved not two mixed-race spouses but a mixed-race and a white spouse: "Under the facts presented the appellant does not have the benefit of assailing the validity of the statute."<ref name=Pascoe_p60>{{harvnb|Pascoe |1996|p=60}}</ref> Dismissing Monks' appeal in 1942, the United States Supreme Court refused to reopen the issue. |

|||

The turning point came with ''[[Perez v. Sharp]]'' (1948), also known as ''Perez v. Lippold''. In ''Perez'', the [[Supreme Court of California]] recognized that bans on interracial marriage violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution. |

|||

==Decision== |

|||

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned the convictions in a unanimous decision (dated June 12, 1967), dismissing the Commonwealth of Virginia's argument that a law forbidding both white and black persons from marrying persons of another race, and providing identical penalties to white and black violators, could not be construed as racially discriminatory. The court ruled that Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute violated both the [[Due Process Clause]] and the [[Equal Protection Clause]] of the Fourteenth Amendment. |

|||

[[Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice]] [[Earl Warren]]'s opinion for the unanimous court held that: |

|||

{{cquote|''Marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man," fundamental to our very existence and survival.... To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.''}} |

|||

The court concluded that anti-miscegenation laws were racist and had been enacted to perpetuate [[white supremacy]]: |

|||

{{cquote|''There is patently no legitimate overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination which justifies this classification. The fact that Virginia prohibits only interracial marriages involving white persons demonstrates that the racial classifications must stand on their own justification, as measures designed to maintain White Supremacy.''}} |

|||

[[Associate Justice]] [[Potter Stewart]] filed a brief [[concurring opinion]]. He reiterated his opinion from ''[[McLaughlin v. Florida]]'' that "it is simply not possible for a state law to be valid under our Constitution which makes the criminality of an act depend upon the race of the actor." |

|||

==Implications of the decision== |

|||

===For interracial marriage=== |

|||

Despite the Supreme Court's decision, anti-miscegenation laws remained on the books in several states, although the decision had made them unenforceable. In 2000, [[Alabama]] became the last state to adapt its laws to the Supreme Court's decision, by removing a provision prohibiting mixed-race marriage from its state constitution through a [[ballot initiative]]. 60% of voters voted for the removal of the anti-miscegenation rule, and 40% against.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2000/11/12/weekinreview/november-5-11-marry-at-will.html |title=November 5–11; Marry at Will |work=New York Times |date=November 12, 2000 |accessdate=May 27, 2009 |quote=The margin by which the measure passed was itself a statement. A clear majority, 60 percent, voted to remove the miscegenation statute from the state constitution, but 40 percent of Alabamans -- nearly 526,000 people -- voted to keep it. | first=Somini | last=Sengupta}}</ref> |

|||

After ''Loving v. Virginia'', the number of interracial marriages continued to increase across the United States<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/18090277/ns/us_news-life/t/after-years-interracial-marriage-flourishing/#.UMkscbZ1PZw |title=Interracial marriage flourishes in U.S. |publisher=MSNBC |date=April 15, 2007 |accessdate=December 13, 2012}}</ref> and in the South. In Georgia, for instance, the number of interracial marriages increased from 21 in 1967 to 115 in 1970.<ref>Aldridge, ''The Changing Nature of Interracial Marriage in Georgia: A Research Note'', 1973</ref> |

|||

===For same-sex marriage=== |

|||

''Loving v. Virginia'' is discussed in the context of the public debate about [[same-sex marriage in the United States]].<ref>{{cite web|last=Trei |first=Lisa |url=http://news.stanford.edu/pr/2007/pr-rosenfeld-061307.html |title=''Loving v. Virginia'' provides roadmap for same-sex marriage advocates |publisher=News.stanford.edu |date=June 13, 2007 |accessdate=December 13, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

In ''Hernandez v. Robles'' (2006), the majority opinion of the [[New York Court of Appeals]], that state's highest court, declined to rely on the ''Loving'' case when deciding whether a right to same-sex marriage existed, holding that "the historical background of ''Loving'' is different from the history underlying this case."<ref name="hernandezvrobles">[http://www.courts.state.ny.us/reporter/3dseries/2006/2006_05239.htm ''Hernandez v. Robles''], 855 NE.3d 1 (N.Y. 2006). Retrieved July 12, 2008.</ref> In the 2010, federal district court decision in ''[[Perry v. Schwarzenegger]]'', which overturned [[California Proposition 8 (2008)|California's Proposition 8]] (which restricted marriage to opposite-sex couples), Judge [[Vaughn R. Walker]] cited ''Loving v. Virginia'' to conclude that "the [constitutional] right to marry protects an individual's choice of marital partner regardless of gender".<ref>[http://www.equalrightsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/35374462-Prop-8-Ruling-FINAL.pdf ''Perry v. Schwarzenegger''], 704 F.Supp.2d 921 (N.D.Cal. 2010).</ref> On more narrow grounds, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/08/us/marriage-ban-violates-constitution-court-rules.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=tha2 |first1=Adam |last1=Nagoruney |date=February 7, 2012 |title=Court Strikes Down Ban on Gay Marriage in California |publisher=New York Times |accessdate=February 8, 2012}}</ref><ref name="9th">[http://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/general/2012/02/07/1016696com.pdf ''Perry v. Brown''], 671 F.3d 1052 (9th Cir. 2012). Retrieved February 8, 2012.</ref> |

|||

In June 2007, on the 40th anniversary of the issuance of the Supreme Court's decision in ''Loving'', commenting on the comparison between interracial marriage and same-sex marriage, Mildred Loving issued a statement in relation to ''Loving v. Virginia'' and its mention in the ongoing court case ''[[Hollingsworth v. Perry]]'': |

|||

{{cquote|''I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry... I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight, seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.''}} |

|||

In December 2013, the [[United States District Court for the District of Utah]] repeatedly cited ''Loving'' in its decision ''[[Kitchen v. Herbert]]'', which held unconstitutional Utah's ban on same-sex marriage. |

|||

==In popular culture== |

|||

* In the United States, June 12, the date of the decision, has become known as [[Loving Day]], an annual unofficial celebration of interracial marriages. |

|||

* The story of the Lovings became the basis of two films. ''[[Mr. & Mrs. Loving]]'' (1996) was written and directed by [[Richard Friedenberg]] and starred [[Lela Rochon]], [[Timothy Hutton]] and [[Ruby Dee]]. According to Mildred Loving, “Not much of it was very true. The only part of it right was I had three children.”<ref>{{cite news|author=Dionne Walker|publisher=USAToday.com|url=http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-06-10-loving_N.htm|title=Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back |date=June 10, 2007|accessdate=May 8, 2008}}</ref><ref name="iht">{{cite news | title=40 years of interracial marriage: Mildred Loving reflects on breaking the color barrier | agency=Associated Press | authorlink=Associated Press | work=[[International Herald-Tribune]] | date=June 9, 2007 | accessdate=April 28, 2008 | url=http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2007/06/10/america/NA-FEA-GEN-US-Loving-Anniversary.php | quote='Not much of [the film] was very true,' she said on a recent Thursday afternoon. 'The only part of it right was I had three children.'}}</ref> The second film, ''[[The Loving Story]],'' premiered on [[HBO]] on February 14, 2012.<ref name="lovings-hbo">{{cite news|url=http://tv.nytimes.com/2012/02/14/arts/television/the-loving-story-an-hbo-documentary.html|title=Scenes From a Marriage That Segregationists Tried to Break Up|first=Alessandra Stanley|date=February 13, 2012|work=[[The New York Times]]}}</ref> |

|||

* In music, the case has been the subject of [[Drew Brody]]'s 2007 folk-music ''Ballad of Mildred Loving (Loving in Virginia),'' and [[Nanci Griffith]]'s 2009 song ''[[The Loving Kind (Nanci Griffith album)|The Loving Kind]].'' Griffith wrote the song after reading Mildred Loving's obituary in the ''[[New York Times]],'' and received the ACLU's [[Bill of Rights Award]] for it. |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

{{div col|2}} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Aldridge |first=Delores |title=The Changing Nature of Interracial Marriage in Georgia: A Research Note |journal=Journal of Marriage and the Family |volume=35 |issue=4 |year=1973 |pages=641–642 |doi=10.2307/350877 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Annella |first=M. |title=Interracial Marriages in Washington, D.C. |journal=Journal of Negro Education |volume=36 |year=1967 |pages=428–433 |doi=10.2307/2294264 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Barnett |first=Larry |title=Research on International and Interracial Marriages |journal=Marriage and Family Living |volume=25 |issue=1 |year=1963 |pages=105–107 |doi=10.2307/349019 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Brower |first=Brock |title='Irrepressible Intimacies'. Review of ''Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity, and Adoption'', by Randall L. Kennedy |journal=Journal of Blacks in Higher Education |volume=40 |year=2003 |pages=120–124 |doi=10.2307/3134064 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Coolidge |first=David Orgon |title=Playing the Loving Card: Same-Sex Marriage and the Politics of Analogy |journal=BYU Journal of Public Law |volume=12 |year=1998 |issue= |pages=201–238 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=DeCoste |first=F. C. |title=The ''Halpren'' Transformation: Same-Sex Marriage, Civil Society, and the Limits of Liberal Law |journal=Alberta Law Review |volume=41 |year=2003 |issue= |pages=619–642 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Foeman |first=Anita Kathy |lastauthoramp=yes |first2=Teresa |last2=Nance |title=From Miscegenation to Multiculturalism: Perceptions and Stages of Interracial Relationship Development |journal=Journal of Black Studies |volume=29 |issue=4 |year=1999 |pages=540–557 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Hopkins |first=C. Quince |title=Variety in U.S Kinship Practices, Substantive Due Process Analysis and the Right to Marry |journal=BYU Journal of Public Law |volume=18 |year=2004 |issue= |pages=665–679 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Kalmijn |first=Matthijs |title=Intermarriage and Homogamy: Causes, Patterns, Trends |journal=Annual Review of Sociology |volume=24 |issue= |year=1998 |pages=395–421 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Koppelman |first=Andrew |title=The Miscegenation Analogy: Sodomy Law as Sex Discrimination |journal=[[Yale Law Journal]] |volume=98 |issue= |year=1988 |pages=145–164 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Pascoe |first=Peggy |title=Miscegenation Law, Court Cases, and Ideologies of 'Race' in Twentieth-Century America |journal=Journal of American History |volume=83 |issue=1 |year=1996 |pages=44–69 |ref=harv }} |

|||

*{{Cite book |last=Walington |first=Walter |title=Domestic Relations |date=November 1967 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Wildman |first=Stephanie |title=Interracial Intimacy and the Potential for Social Change: Review of ''Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race and Romance'' by Rachel F. Moran |journal=Berkeley Women's Law Journal |volume=17 |year=2002 |pages=153–164 |doi=10.2139/ssrn.309743 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |last=Yancey |first=George |lastauthoramp=yes |first2=Sherelyn |last2=Yancey |title=Interracial Dating: Evidence from Personal Advertisements |journal=Journal of Family Issues |volume=19 |issue=3 |year=1998 |pages=334–348 |doi=10.1177/019251398019003006 }} |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

*{{caselaw source |

|||

|case=''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967) |

|||

|findlaw=http://laws.findlaw.com/us/388/1.html |

|||

|other_source1=UMKC |

|||

|other_url1=http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/loving.html |

|||

}} |

|||

*[http://www.abcnews.go.com/US/story?id=3277875&page=1n ABC News: A Groundbreaking Interracial Marriage; Loving v. Virginia at 40.] Interview with Mildred Jeter Loving & video of original 1967 broadcast. June 14, 2007. |

|||

*[http://www.oyez.org/oyez/resource/case/214/ Resources at Oyez] including complete audio of the oral arguments. |

|||

*[http://www.lovingday.org/ Loving Day: June 12]—commemorating legalization of interracial couples |

|||

*[http://icarusfilms.com/new2012/ls.html The Loving Story]—Nancy Buirski's documentary film |

|||

*[http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=10889047 Loving Decision: 40 Years of Legal Interracial Unions.] National Public Radio: All Things Considered, June 11, 2007. |

|||

* [http://writ.news.findlaw.com/grossman/20070612.html The Fortieth Anniversary of Loving v. Virginia: The Legal Legacy of the Case that Ended Legal Prohibitions on Interracial Marriage] Findlaw commentary by Joanna Grossman. |

|||

*[http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2007/06/10/america/NA-FEA-GEN-US-Loving-Anniversary.php 40 years of interracial marriage: Mildred Loving reflects on breaking the color barrier] AP article in International Herald Tribune |

|||

*{{imdb title|id=0117098|title=Mr. & Mrs. Loving}} |

|||

*[http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/06/us/06loving.html?_r=1&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss&oref=slogin ''New York Times''] article upon the death of Mildred Loving |

|||

*[http://encyclopediavirginia.org/Loving_v_Virginia_1967 Encyclopedia Virginia] ''Loving v. Virginia'' |

|||

*[http://www.economist.com/displayStory.cfm?source=hptextfeature&story_id=11367685 Mildred Loving's Obituary from The Economist] |

|||

*[http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=283998 Chin, Gabriel and Hrishi Karthikeyan, (2002) Asian Law Journal vol. 9 "Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910-1950"] |

|||

{{African-American Civil Rights Movement}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Loving V. Virginia}} |

|||

[[Category:1967 in United States case law]] |

|||

[[Category:Legal history of Virginia]] |

|||

[[Category:Marriage, unions and partnerships in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:Multiracial affairs in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:Race-related legal issues in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:Trials in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:United States Supreme Court cases]] |

|||

[[Category:United States civil rights case law]] |

|||

[[Category:United States equal protection case law]] |

|||

[[Category:United States substantive due process case law]] |

|||

[[Category:1967 in Virginia]] |

|||

[[Category:Cases related to the American Civil Liberties Union]] |

|||

{{Link GA|de}} |

{{Link GA|de}} |

||

Revision as of 21:33, 29 January 2014

| Loving v. Virginia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 10, 1967 Decided June 12, 1967 | |

| Full case name | Richard Perry Loving, Mildred Jeter Loving v. Virginia |

| Citations | 388 U.S. 1 (more) 87 S. Ct. 1817; 18 L. Ed. 2d 1010; 1967 U.S. LEXIS 1082 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Defendants convicted, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 6, 1959); motion to vacate judgment denied, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 22, 1959); affirmed in part, reversed and remanded, 147 S.E.2d 78 (Va. 1966) |

| Holding | |

| The Court declared Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute, the "Racial Integrity Act of 1924", unconstitutional, as a violation of the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Warren, joined by unanimous |

| Concurrence | Stewart |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. XIV; Va. Code §§ 20-58, 20-59 | |

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967),[1] was a landmark civil rights decision of the United States Supreme Court which invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage.

The case was brought by Mildred Loving, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, who had been sentenced to a year in prison in Virginia for marrying each other. Their marriage violated the state's anti-miscegenation statute, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which prohibited marriage between people classified as "white" and people classified as "colored." The Supreme Court's unanimous decision held this prohibition was unconstitutional, overturning Pace v. Alabama (1883) and ending all race-based legal restrictions on marriage in the United States.

The decision was followed by an increase in interracial marriages in the U.S., and is remembered annually on Loving Day, June 12. It has been the subject of two movies as well as songs. In the 2010s, it again became relevant in the context of the debate about same-sex marriage in the United States.

Background

Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States had been in place in certain states since before the United States declared independence.

Plaintiffs

The plaintiffs in the case were Mildred Delores Loving, née Jeter (July 22, 1939 – May 2, 2008), a woman of African-American and Rappahannock Native American descent,[2][3][4] and Richard Perry Loving (October 29, 1933 – June 1975),[5] a white man.

The couple had three children: Donald, Peggy, and Sidney. Richard Loving died aged 41 in 1975, when a drunk driver struck his car in Caroline County, Virginia.[6] Mildred Loving lost her right eye in the same accident. She died of pneumonia on May 2, 2008, in Milford, Virginia, aged 68.[7]

Criminal proceedings

At the age of 18, Mildred became pregnant, and in June 1958 the couple traveled to Washington, D.C. to marry, thereby evading Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which made interracial marriage a crime. They returned to the small town of Central Point, Virginia. Based on an anonymous tip,[8] local police raided their home at night, hoping to find them having sex, which was also a crime according to Virginia law. When the officers found the Lovings sleeping in their bed, Mildred pointed out their marriage certificate on the bedroom wall. That certificate became the evidence for the criminal charge of "cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth" that was brought against them.

The Lovings were charged under Section 20-58 of the Virginia Code, which prohibited interracial couples from being married out of state and then returning to Virginia, and Section 20-59, which classified miscegenation as a felony, punishable by a prison sentence of between one and five years. The trial judge in the case, Leon M. Bazile, echoing Johann Friedrich Blumenbach's 18th-century interpretation of race:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.

On January 6, 1959, the Lovings pled guilty and were sentenced to one year in prison, with the sentence suspended for 25 years on condition that the couple leave the state of Virginia. They did so, moving to the District of Columbia.

Appellate proceedings

In 1964,[9] frustrated by their inability to travel together to visit their families in Virginia and social isolation and financial difficulties in Washington, Mildred Loving wrote in protest to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Kennedy referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).[8]

The ACLU filed a motion on behalf of the Lovings in the state trial court to vacate the judgment and set aside the sentence on the grounds that the violated statutes ran counter to the Fourteenth Amendment. This set in motion a series of lawsuits which ultimately reached the Supreme Court.

On October 28, 1964, after the Lovings' motion still had not been decided, they brought a class action suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. On January 22, 1965, the three-judge district court decided to allow the Lovings to present their constitutional claims to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. Virginia Supreme Court Justice Harry L. Carrico (later Chief Justice of the Court) wrote an opinion for the court upholding the constitutionality of the anti-miscegenation statutes and, after modifying the sentence, affirmed the criminal convictions. Ignoring United States Supreme Court precedent, Carrico cited as authority the Virginia Supreme Court's own decision in Naim v. Naim (1955), also arguing that the case at hand was not a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause because both the white and the non-white spouse were punished equally for the crime of miscegenation, an argument similar to that made by the United States Supreme Court in 1883 in Pace v. Alabama.

The Lovings, supported by the ACLU, appealed the decision to the United States Supreme Court. They did not attend the oral arguments in Washington, but their lawyer, Bernard S. Cohen, conveyed the message he had been given by Richard Loving to the court: "Mr. Cohen, tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."[10]

Precedents

Before Loving v. Virginia, there had been several cases on the subject of interracial relations. In Pace v. Alabama (1883), the Supreme Court ruled that the conviction of an Alabama couple for interracial sex, affirmed on appeal by the Alabama Supreme Court, did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. Interracial marital sex was deemed a felony, whereas extramarital sex ("adultery or fornication") was only a misdemeanor. On appeal, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the criminalization of interracial sex was not a violation of the equal protection clause because whites and non-whites were punished in equal measure for the offense of engaging in interracial sex. The court did not need to affirm the constitutionality of the ban on interracial marriage that was also part of Alabama's anti-miscegenation law, since the plaintiff, Mr. Pace, had chosen not to appeal that section of the law. After Pace v. Alabama, the constitutionality of anti-miscegenation laws banning marriage and sex between whites and non-whites remained unchallenged until the 1920s.

In Kirby v. Kirby (1921), Mr. Kirby asked the state of Arizona for an annulment of his marriage. He charged that his marriage was invalid because his wife was of ‘negro’ descent, thus violating the state's anti-miscegenation law. The Arizona Supreme Court judged Mrs. Kirby’s race by observing her physical characteristics and determined that she was of mixed race, therefore granting Mr. Kirby’s annulment.[11]

In the Monks case (Estate of Monks, 4. Civ. 2835, Records of California Court of Appeals, Fourth district), the Superior Court of San Diego County in 1939 decided to invalidate the marriage of Marie Antoinette and Allan Monks because she was deemed to have "one eighth negro blood." The court case involved a legal challenge over the conflicting wills that had been left by the late Allan Monks, an old one in favor of a friend named Ida Lee and a newer one in favor of his wife. Lee's lawyers charged that the marriage of the Monkses, which had taken place in Arizona, was invalid under Arizona state law because Marie Antoinette was "a Negro" and Alan had been white. Despite conflicting testimony by various expert witnesses, the judge defined Mrs. Monks' race by relying on the anatomical "expertise" of a surgeon. The judge ignored the arguments of an anthropologist and a biologist that it was impossible to tell a person's race from physical characteristics.[12]

Monks then challenged the Arizona anti-miscegenation law itself, taking her case to the California Court of Appeals, Fourth District. Monks' lawyers pointed out that the anti-miscegenation law effectively prohibited Monks as a mixed-race person from marrying anyone: "As such, she is prohibited from marrying a negro or any descendant of a negro, a Mongolian or an Indian, a Malay or a Hindu, or any descendants of any of them. Likewise ... as a descendant of a negro she is prohibited from marrying a Caucasian or a descendant of a Caucasian...." The Arizona anti-miscegenation statute thus prohibited Monks from contracting a valid marriage in Arizona, and was therefore an unconstitutional constraint on her liberty. The court, however, dismissed this argument as inapplicable, because the case presented involved not two mixed-race spouses but a mixed-race and a white spouse: "Under the facts presented the appellant does not have the benefit of assailing the validity of the statute."[13] Dismissing Monks' appeal in 1942, the United States Supreme Court refused to reopen the issue.

The turning point came with Perez v. Sharp (1948), also known as Perez v. Lippold. In Perez, the Supreme Court of California recognized that bans on interracial marriage violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution.

Decision

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned the convictions in a unanimous decision (dated June 12, 1967), dismissing the Commonwealth of Virginia's argument that a law forbidding both white and black persons from marrying persons of another race, and providing identical penalties to white and black violators, could not be construed as racially discriminatory. The court ruled that Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute violated both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Chief Justice Earl Warren's opinion for the unanimous court held that:

Marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man," fundamental to our very existence and survival.... To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.

The court concluded that anti-miscegenation laws were racist and had been enacted to perpetuate white supremacy:

There is patently no legitimate overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination which justifies this classification. The fact that Virginia prohibits only interracial marriages involving white persons demonstrates that the racial classifications must stand on their own justification, as measures designed to maintain White Supremacy.

Associate Justice Potter Stewart filed a brief concurring opinion. He reiterated his opinion from McLaughlin v. Florida that "it is simply not possible for a state law to be valid under our Constitution which makes the criminality of an act depend upon the race of the actor."

Implications of the decision

For interracial marriage

Despite the Supreme Court's decision, anti-miscegenation laws remained on the books in several states, although the decision had made them unenforceable. In 2000, Alabama became the last state to adapt its laws to the Supreme Court's decision, by removing a provision prohibiting mixed-race marriage from its state constitution through a ballot initiative. 60% of voters voted for the removal of the anti-miscegenation rule, and 40% against.[14]

After Loving v. Virginia, the number of interracial marriages continued to increase across the United States[15] and in the South. In Georgia, for instance, the number of interracial marriages increased from 21 in 1967 to 115 in 1970.[16]

For same-sex marriage

Loving v. Virginia is discussed in the context of the public debate about same-sex marriage in the United States.[17]

In Hernandez v. Robles (2006), the majority opinion of the New York Court of Appeals, that state's highest court, declined to rely on the Loving case when deciding whether a right to same-sex marriage existed, holding that "the historical background of Loving is different from the history underlying this case."[18] In the 2010, federal district court decision in Perry v. Schwarzenegger, which overturned California's Proposition 8 (which restricted marriage to opposite-sex couples), Judge Vaughn R. Walker cited Loving v. Virginia to conclude that "the [constitutional] right to marry protects an individual's choice of marital partner regardless of gender".[19] On more narrow grounds, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.[20][21]

In June 2007, on the 40th anniversary of the issuance of the Supreme Court's decision in Loving, commenting on the comparison between interracial marriage and same-sex marriage, Mildred Loving issued a statement in relation to Loving v. Virginia and its mention in the ongoing court case Hollingsworth v. Perry:

I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry... I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight, seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.

In December 2013, the United States District Court for the District of Utah repeatedly cited Loving in its decision Kitchen v. Herbert, which held unconstitutional Utah's ban on same-sex marriage.

In popular culture

- In the United States, June 12, the date of the decision, has become known as Loving Day, an annual unofficial celebration of interracial marriages.

- The story of the Lovings became the basis of two films. Mr. & Mrs. Loving (1996) was written and directed by Richard Friedenberg and starred Lela Rochon, Timothy Hutton and Ruby Dee. According to Mildred Loving, “Not much of it was very true. The only part of it right was I had three children.”[22][23] The second film, The Loving Story, premiered on HBO on February 14, 2012.[24]

- In music, the case has been the subject of Drew Brody's 2007 folk-music Ballad of Mildred Loving (Loving in Virginia), and Nanci Griffith's 2009 song The Loving Kind. Griffith wrote the song after reading Mildred Loving's obituary in the New York Times, and received the ACLU's Bill of Rights Award for it.

References

- ^ Full text of the opinion in Loving v. Virginia courtesy of Findlaw.com.

- ^ Lawing, Charles B. (2000). "Loving v. Virginia and the Hegemony of "Race"" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back

- ^ "Social Security Death Index (Mildred D. Loving) [database on-line]". United States: The Generations Network. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "Social Security Death Index (Richard Loving) [database on-line]". United States: The Generations Network. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "RICHARD P. LOVING; IN LAND MARK SUIT; Figure in High Court Ruling on Miscegenation Dies". The New York Times. July 1, 1975.

- ^ Douglas Martin (May 6, 2008). "Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

Mildred Loving, a black woman whose anger over being banished from Virginia for marrying a white man led to a landmark Supreme Court ruling overturning state miscegenation laws, died on May 2 at her home in Central Point, Va. She was 68.

- ^ a b Martin, Douglas. "Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68", New York Times, May 6, 2008.

- ^ "Mildred Loving, Key Figure in Civil Rights Era, Dies", PBS Online News Hour, May 6, 2008

- ^ Kate Sheppard, "'The Loving Story': How an Interracial Couple Changed a Nation", Mother Jones, Feb 13, 2012. Also quoted in Loving v. Virginia (1967), Encyclopedia Virginia

- ^ Pascoe 1996, pp. 49–51

- ^ Pascoe 1996, p. 56

- ^ Pascoe 1996, p. 60

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (November 12, 2000). "November 5–11; Marry at Will". New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

The margin by which the measure passed was itself a statement. A clear majority, 60 percent, voted to remove the miscegenation statute from the state constitution, but 40 percent of Alabamans -- nearly 526,000 people -- voted to keep it.

- ^ "Interracial marriage flourishes in U.S." MSNBC. April 15, 2007. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ Aldridge, The Changing Nature of Interracial Marriage in Georgia: A Research Note, 1973

- ^ Trei, Lisa (June 13, 2007). "Loving v. Virginia provides roadmap for same-sex marriage advocates". News.stanford.edu. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ Hernandez v. Robles, 855 NE.3d 1 (N.Y. 2006). Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- ^ Perry v. Schwarzenegger, 704 F.Supp.2d 921 (N.D.Cal. 2010).

- ^ Nagoruney, Adam (February 7, 2012). "Court Strikes Down Ban on Gay Marriage in California". New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ Perry v. Brown, 671 F.3d 1052 (9th Cir. 2012). Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ Dionne Walker (June 10, 2007). "Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back". USAToday.com. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ "40 years of interracial marriage: Mildred Loving reflects on breaking the color barrier". International Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. June 9, 2007. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

'Not much of [the film] was very true,' she said on a recent Thursday afternoon. 'The only part of it right was I had three children.'

- ^ "Scenes From a Marriage That Segregationists Tried to Break Up". The New York Times. February 13, 2012.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help)

Further reading

- Aldridge, Delores (1973). "The Changing Nature of Interracial Marriage in Georgia: A Research Note". Journal of Marriage and the Family. 35 (4): 641–642. doi:10.2307/350877.

- Annella, M. (1967). "Interracial Marriages in Washington, D.C.". Journal of Negro Education. 36: 428–433. doi:10.2307/2294264.

- Barnett, Larry (1963). "Research on International and Interracial Marriages". Marriage and Family Living. 25 (1): 105–107. doi:10.2307/349019.

- Brower, Brock (2003). "'Irrepressible Intimacies'. Review of Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity, and Adoption, by Randall L. Kennedy". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 40: 120–124. doi:10.2307/3134064.

- Coolidge, David Orgon (1998). "Playing the Loving Card: Same-Sex Marriage and the Politics of Analogy". BYU Journal of Public Law. 12: 201–238.

- DeCoste, F. C. (2003). "The Halpren Transformation: Same-Sex Marriage, Civil Society, and the Limits of Liberal Law". Alberta Law Review. 41: 619–642.

- Foeman, Anita Kathy; Nance, Teresa (1999). "From Miscegenation to Multiculturalism: Perceptions and Stages of Interracial Relationship Development". Journal of Black Studies. 29 (4): 540–557.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Hopkins, C. Quince (2004). "Variety in U.S Kinship Practices, Substantive Due Process Analysis and the Right to Marry". BYU Journal of Public Law. 18: 665–679.

- Kalmijn, Matthijs (1998). "Intermarriage and Homogamy: Causes, Patterns, Trends". Annual Review of Sociology. 24: 395–421.

- Koppelman, Andrew (1988). "The Miscegenation Analogy: Sodomy Law as Sex Discrimination". Yale Law Journal. 98: 145–164.

- Pascoe, Peggy (1996). "Miscegenation Law, Court Cases, and Ideologies of 'Race' in Twentieth-Century America". Journal of American History. 83 (1): 44–69.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walington, Walter (November 1967). Domestic Relations.

- Wildman, Stephanie (2002). "Interracial Intimacy and the Potential for Social Change: Review of Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race and Romance by Rachel F. Moran". Berkeley Women's Law Journal. 17: 153–164. doi:10.2139/ssrn.309743.

- Yancey, George; Yancey, Sherelyn (1998). "Interracial Dating: Evidence from Personal Advertisements". Journal of Family Issues. 19 (3): 334–348. doi:10.1177/019251398019003006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- Text of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) is available from: Findlaw UMKC

- ABC News: A Groundbreaking Interracial Marriage; Loving v. Virginia at 40. Interview with Mildred Jeter Loving & video of original 1967 broadcast. June 14, 2007.

- Resources at Oyez including complete audio of the oral arguments.

- Loving Day: June 12—commemorating legalization of interracial couples

- The Loving Story—Nancy Buirski's documentary film

- Loving Decision: 40 Years of Legal Interracial Unions. National Public Radio: All Things Considered, June 11, 2007.

- The Fortieth Anniversary of Loving v. Virginia: The Legal Legacy of the Case that Ended Legal Prohibitions on Interracial Marriage Findlaw commentary by Joanna Grossman.

- 40 years of interracial marriage: Mildred Loving reflects on breaking the color barrier AP article in International Herald Tribune

- Mr. & Mrs. Loving at IMDb

- New York Times article upon the death of Mildred Loving

- Encyclopedia Virginia Loving v. Virginia

- Mildred Loving's Obituary from The Economist

- Chin, Gabriel and Hrishi Karthikeyan, (2002) Asian Law Journal vol. 9 "Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910-1950"

- 1967 in United States case law

- Legal history of Virginia

- Marriage, unions and partnerships in the United States

- Multiracial affairs in the United States

- Race-related legal issues in the United States

- Trials in the United States

- United States Supreme Court cases

- United States civil rights case law

- United States equal protection case law

- United States substantive due process case law

- 1967 in Virginia

- Cases related to the American Civil Liberties Union