Psychiatry: Difference between revisions

simpler\ |

→History: radically condense now that a separate sub-article exists |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{ |

{{main|History of psychiatry}} |

||

{{see also|History of psychiatric institutions}} |

|||

| ⚫ | The term psychiatry (Greek "ψυχιατρική", ''psychiatrikē'') which comes from the Greek "ψυχή" (''psychē'': "soul or mind") and "ιατρός" (''iatros'': "healer") was coined by [[Johann Christian Reil]] in 1808.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Naragon|first1=Steve|title=Johann Christian Reil (1759-1813)|url=http://www.manchester.edu/kant/Bio/FullBio/ReilJC.html|date=11 Jul 2010}}</ref>{{Verify credibility|date=November 2014|reason=Author says this is a chapter draft for 'The Dictionary of Eighteenth Century German Philosophers', Manfred Kuehn and Heiner Klemme (eds.) London/New York: Continuum, 2010.}}<ref>{{cite journal | author = Marneros A | title = Psychiatry’s 200th birthday | journal = British Journal of Psychiatry' | volume = 193 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–3 | date = July 2008 | pmid = 18700209 | doi = 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051367 | url = http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/abstract/193/1/1 }}</ref> |

||

===Ancient=== |

|||

| ⚫ | During the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with [[psychosis|psychotic]] traits, were considered [[supernatural]] in origin,<ref name=Elkes13>Elkes, A. & Thorpe, J.G. (1967). ''A Summary of Psychiatry''. London: Faber & Faber, p. 13.</ref> a view which existed throughout [[ancient Greece]] and [[ancient Rome|Rome]].<ref name=Elkes13/> Religious leaders often turned to versions of [[exorcism]] to treat mental disorders often utilizing methods that many consider to be cruel and/or barbaric methods.<ref name=Elkes13/> |

||

Specialty in psychiatry can be traced in Ancient India. The oldest texts on psychiatry include the ayurvedic text, [[Charaka Samhita]].<ref>{{cite book|title=Cultural Sociology of Mental Illness: An A-to-Z Guide, Volume 1|page=386|publisher=[[Sage Publications]]|author=Andrew Scull}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Health and Illness: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia|page=42|publisher=ABC-CLIO|author=David Levinson, Laura Gaccione|year=1997}}</ref> Some of the first hospitals for curing mental illness were established during 3rd century BCE.<ref>{{cite book|title=Faith and Mental Health: Religious Resources for Healing|page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=jt5RmK_h2jgC&pg=PA36 36]|first=Harold G.|last=Koenig|publisher=Templeton Foundation Press|date=2009|isbn=978-1-59947-078-8}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | [[File:Plan of the first Bethlem Hospital.png|thumb|Plan of the [[Bethlem Royal Hospital]], an early public asylum for the mentally ill.|alt=A map of the original Bethlem Hospital site]][[psychiatric hospital|Specialist hospitals]] were built in [[Baghdad]] in 705 AD,<ref>{{cite book|title=Religion and Psychiatry: Beyond Boundaries|page=202|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|author=Peter Verhagen, Herman M. Van Praag, Juan José López-Ibor, Jr., John Cox, Driss Moussaoui}}</ref> followed by [[Fes]] in the early 8th century, and [[Cairo]] in 800 AD.{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} Specialist hospitals such as [[Bethlem Royal Hospital]] in [[London]] were built in [[Middle Ages|medieval Europe]] from the 13th century to treat mental disorders, but were used only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment.<ref name=Shorter4>{{harvnb|Shorter|1997|p=4}}.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | During the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with [[psychosis|psychotic]] traits, were considered [[supernatural]] in origin,<ref name=Elkes13>Elkes, A. & Thorpe, J.G. (1967). ''A Summary of Psychiatry''. London: Faber & Faber, p. 13.</ref> a view which existed throughout [[ancient Greece]] and [[ancient Rome|Rome]].<ref name=Elkes13/> |

||

The beginning of psychiatry as a medical specialty is dated to the middle of the nineteenth century,{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=1}} although its germination can be traced to the late eighteenth century. In the late 17th century, privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. |

|||

Some of the early manuals about mental disorders were created by the Greeks.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=1}} In the 4th century BCE, [[Hippocrates]] theorized that physiological abnormalities may be the root of mental disorders.<ref name=Elkes13/> In 4th to 5th Century B.C. Greece, [[Hippocrates]] wrote that he visited [[Democritus]] and found him in his garden cutting open animals. Democritus explained that he was attempting to discover the cause of madness and melancholy. Hippocrates praised his work. Democritus had with him a book on madness and melancholy.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Burton|first1=Robert|title=The Anatomy of Melancholy: What it is with All the Kinds, Causes, Symptoms, Prognostics, and Several Cures of it: in Three Partitions, with Their Several Sections, Members and Subsections Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically Opened and Cut Up|date=1881|publisher=Chatto & Windus|location=London|ol=3149647W|pages=[http://books.google.com/books?id=DAIGAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA22 22], [http://books.google.com/books?id=DAIGAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA24 24]}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1713 the Bethel Hospital Norwich was opened, the first purpose-built asylum in England.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/social-innovation/the-bethel-hospital.htm/|title=The Bethel Hospital|publisher=Norwich HEART}}</ref> In 1656, [[Louis XIV of France]] created a public system of hospitals for those suffering from mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=5}} |

||

| ⚫ | During the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] attitudes towards the mentally ill began to change. It came to be viewed as a disorder that required compassionate treatment. In 1758 English physician [[William Battie]] wrote his ''Treatise on Madness'' on the management of [[mental disorder]]. It was a critique aimed particularly at the [[Bethlem Hospital]], where a conservative regime continued to use barbaric custodial treatment. Battie argued for a tailored management of patients entailing cleanliness, good food, fresh air, and distraction from friends and family. He argued that mental disorder originated from dysfunction of the material brain and body rather than the internal workings of the mind.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Laffey P | year = 2003 | title = Psychiatric therapy in Georgian Britain | url = http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=179425 | journal = Psychological Medicine | volume = 2003 | issue = 33| pages = 1285–1297 | doi = 10.1017/S0033291703008109 }}</ref>{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=9}} |

||

Religious leaders often turned to versions of [[exorcism]] to treat mental disorders often utilizing methods that many consider to be cruel and/or barbaric methods.<ref name=Elkes13/> |

|||

===Middle Ages=== |

|||

{{Main|Psychology in medieval Islam}} |

|||

| ⚫ | [[psychiatric hospital|Specialist hospitals]] were built in [[Baghdad]] in 705 AD,<ref>{{cite book|title=Religion and Psychiatry: Beyond Boundaries|page=202|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|author=Peter Verhagen, Herman M. Van Praag, Juan José López-Ibor, Jr., John Cox, Driss Moussaoui}}</ref> followed by [[Fes]] in the early 8th century, and [[Cairo]] in 800 AD.{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} |

||

Physicians who wrote on mental disorders and their treatment in the Medieval Islamic period included [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi]] (Rhazes), the [[Arab]] physician Najab ud-din Muhammad{{Citation needed|date=November 2011}}, and Abu Ali al-Hussain ibn Abdallah ibn Sina, known in the West as [[Avicenna]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Namazi|first=Mohamed Reza |date=November 2001 |title=Avicenna, 980-1037. |journal=American Journal of Psychiatry |volume=158 |issue=11 |page=1796 |pmid=11691684 |doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1796 |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1796 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Shoja|first1=Mohammadali M. |last2=Tubbs|first2=R. Shane |date=February 2007 |title=The disorder of love in the Canon of Avicenna (A.D. 980-1037). |journal=American Journal of Psychiatry |volume=164 |issue=2 |pages=228-229 |pmid=17267784 |doi=10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.228x |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.228 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Safavi-Abbasi|first1=S |last2=Brasiliense|first2=LB |last3=Workman|first3=RK |last4=Talley|first4=MC |last5=Feiz-Erfan|first5=I |last6=Theodore|first6=N |last7=Spetzler|first7=RF |last8=Preul|first8=MC |date=July 2007 |title=The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire |journal=Neurosurgical Focus |volume=23 |issue=1 |page=E13 |pmid=17961058 |doi=10.3171/FOC-07/07/E13 |url=http://thejns.org/doi/abs/10.3171/FOC-07/07/E13 }}</ref> |

|||

Specialist hospitals were built in [[Middle Ages|medieval Europe]] from the 13th century to treat mental disorders but were utilized only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment.<ref name=Shorter4>{{harvnb|Shorter|1997|p=4}}.</ref> |

|||

===Early modern period=== |

|||

[[File:Plan of the first Bethlem Hospital.png|thumb|Plan of the [[Bethlem Royal Hospital]], an early public asylum for the mentally ill.|alt=A map of the original Bethlem Hospital site]] |

|||

Founded in the 13th century, [[Bethlem Royal Hospital]] in [[London]] was one of the oldest lunatic asylums.<ref name=Shorter4/> In the late 17th century, privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that [[Bethlem Royal Hospital]], [[London]] had "below stairs a parlor, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in".<ref>{{cite book|author=Allderidge, Patricia|chapter=Management and Mismanagement at Bedlam, 1547–1633|editor=Webster, Charles|title=Health, Medicine and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century|year=1979|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|page=145|isbn=9780521226431|chapterurl=http://books.google.ie/books?id=g588AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA141}}</ref> Inmates who were deemed dangerous or disturbing were chained, but Bethlem was an otherwise open building for its inhabitants to roam around its confines and possibly throughout the general neighborhood in which the hospital was situated.<ref>{{cite book|author=Stevenson, Christine. The Architecture of Bethlem at Moorfields |author2=Jonathan Andrews, Asa Briggs, Roy Porter, Penny Tucker & Keir Waddington|title=History of Bethlem|year=1997|publisher=Routledge|location=London & New York|isbn=0415017734|url=http://books.google.ie/books?id=NdIypYX6KIwC&dq|page=51}}</ref> In 1676, Bethlem expanded into newly built premises at [[Moorfields]] with a capacity for 100 inmates.<ref>{{Cite book|edition=Ill. |origyear= 1987|publisher=Tempus|isbn=9780752437309|last=Porter|first=Roy|title=Madmen: A Social History of Madhouses, Mad-Doctors & Lunatics|location=Stroud|year=2006}}</ref>{{rp|155}}<ref>{{cite journal| volume = 38| issue = 1| pages = 27–51| last = Winston| first = Mark| title = The Bethel at Norwich: An Eighteenth-Century Hospital for Lunatics| journal = Medical History| year = 1994| doi=10.1017/s0025727300056039}}</ref>{{rp|27}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In 1621, [[Oxford University]] mathematician, astrologer, and scholar [[Robert Burton (scholar)|Robert Burton]] published one of the earliest treatises on mental illness, ''[[The Anatomy of Melancholy]], What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up''. Burton thought that there was "no greater cause of melancholy than idleness, no better cure than business." Unlike English philosopher of science [[Francis Bacon]], Burton argued that knowledge of the mind, not [[natural science]], is humankind's greatest need.<ref>Abrams, Howard Meyers, ed. (1999) The Norton Anthology of English Literature; Vol. 1; 7th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Co Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-97487-4</ref> |

|||

In 1656, [[Louis XIV of France]] created a public system of hospitals for those suffering from mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=5}} |

|||

===Humanitarian reform=== |

|||

{{Main|Moral treatment}} |

|||

[[File:Philippe Pinel à la Salpêtrière.jpg|thumb|250px|Dr. Philippe Pinel at the Salpêtrière, 1795 by [[Tony Robert-Fleury]]. Pinel ordering the removal of chains from patients at the Paris Asylum for insane women.]] |

[[File:Philippe Pinel à la Salpêtrière.jpg|thumb|250px|Dr. Philippe Pinel at the Salpêtrière, 1795 by [[Tony Robert-Fleury]]. Pinel ordering the removal of chains from patients at the Paris Asylum for insane women.]] |

||

| ⚫ | The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor [[Philippe Pinel]] and the English [[Quaker]] [[William Tuke]].<ref name=Elkes13/> In 1792 Pinel became the chief physician at the [[Bicêtre Hospital]]. Patients were allowed to move freely about the hospital grounds, and eventually dark dungeons were replaced with sunny, well-ventilated rooms. Pinel's student and successor, [[Jean Esquirol]] (1772–1840), went on to help establish 10 new mental hospitals that operated on the same principles.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Gerard DL |title=Chiarugi and Pinel considered: Soul's brain/person's mind |journal=J Hist Behav Sci |volume=33 |issue=4 |pages=381–403 |year=1998 |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/45798/abstract? |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1520-6696(199723)33:4<381::AID-JHBS3>3.0.CO;2-S}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | During the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] attitudes towards the mentally ill began to change. It came to be viewed as a disorder that required compassionate treatment |

||

| ⚫ | Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread into the 19th century. At the [[Lincoln Asylum]] in England, [[Robert Gardiner Hill]], with the support of [[Edward Parker Charlesworth]], pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with — a situation he finally achieved in 1838. In 1839 Sergeant John Adams and Dr. [[John Conolly]] were impressed by the work of Hill, and introduced the method into their [[Hanwell Asylum]], by then the largest in the country.<ref name="Suzuki">{{cite journal | author = Suzuki A | title = The politics and ideology of non-restraint: the case of the Hanwell Asylum. | journal = Medical History | volume = 39 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–17 | date = January 1995 | pmid = 7877402 | pmc = 1036935 | doi = 10.1017/s0025727300059457 | publisher = Wellcome Institute | authorlink = | location = 183 Euston Road, London NWI 2BE. | issn = }}</ref><ref name="taom">Edited by: Bynum, W.F.;Porter, Roy;Shepherd, Michael (1988) The Anatomy of Madness: Essays in the history of psychiatry. Vol.3. The Asylum and its psychiatry. Routledge. London EC4</ref> |

||

Thirty years later, then ruling monarch in England [[George III of the United Kingdom|George III]] was known to be suffering from a mental disorder.<ref name= Elkes13/> Following the King's [[remission (medicine)|remission]] in 1789, mental illness came to be seen as something which could be treated and cured.<ref name=Elkes13/> The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor [[Philippe Pinel]] and the English [[Quaker]] [[William Tuke]].<ref name=Elkes13/> |

|||

The modern era of institutionalized provision for the care of the mentally ill, began in the early 19th century with a large state-led effort. In England, the [[Lunacy Act 1845]] was an important landmark in the treatment of the mentally ill, as it explicitly changed the status of [[mental illness|mentally ill]] people to [[patients]] who required treatment. All asylums were required to have written regulations and to have a resident qualified [[physician]].<ref name="Wright, 1999"/> In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country. |

|||

In 1792 Pinel became the chief physician at the [[Bicêtre Hospital]]. In 1797, Pussin first freed patients of their chains and banned physical punishment, although straitjackets could be used instead.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Weiner DB | title = The apprenticeship of Philippe Pinel: a new document, "observations of Citizen Pussin on the insane" | journal = Am J Psychiatry | volume = 136 | issue = 9 | pages = 1128–34 | date = September 1979 | pmid = 382874 | url = http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=382874 | doi=10.1176/ajp.136.9.1128}}</ref><ref name="bukelic">{{cite book|last=Bukelic |first=Jovan|title=Neuropsihijatrija za III razred medicinske skole|editor=Mirjana Jovanovic|publisher=Zavod za udzbenike i nastavna sredstva|location=Belgrade|year=1995|edition=7th|page=7|chapter=2|isbn=86-17-03418-1|accessdate=27 July 2011|language=Serbian}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | In the United States, the erection of state asylums began with the first law for the creation of one in New York, passed in 1842. The [[Utica State Hospital]] was opened approximately in 1850. Many state hospitals in the United States were built in the 1850s and 1860s on the [[Kirkbride Plan]], an architectural style meant to have curative effect.<ref>{{cite book|last=Yanni|first=Carla|title=The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States|publisher=Minnesota University Press|location=Minneapolis|year=2007|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=fJOC_rSW1kgC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=&f=false | isbn=978-0-8166-4939-6}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=34}} By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. However, the idea that mental illness could be ameliorated through institutionalization ran into difficulties.<ref name=Shorter46>{{harvnb|Shorter|1997|p=46}}.</ref> Psychiatrists were pressured by an ever increasing patient population,<ref name=Shorter46/> and asylums again becae almost indistinguishable from custodial institutions,<ref name=Rothman>Rothman, D.J. (1990). ''The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic''. Boston: Little Brown, p. 239. ISBN 978-0-316-75745-4</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:RetreatOriginalBuildingssm.jpg|thumb|300px|left|The [[York Retreat]] (c.1796) was built by [[William Tuke]], a pioneer of moral treatment for the insane.]] |

|||

[[William Tuke]] led the development of a radical new type of institution in northern England, following the death of a fellow Quaker in a local asylum in 1790.<ref name="Cherry">{{citation|last=Cherry|first=Charles L.|title=A Quiet Haven: Quakers, Moral Treatment, and Asylum Reform|location=London & Toronto|publisher=Associated University Presses|year=1989}}</ref>{{rp|84–85}} <ref name="Digby">{{citation|last=Digby|first=Anne|title=Madness, Morality and Medicine: A Study of the York Retreat|location=Cambridge|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1983}}</ref>{{rp|30}} <ref name="Glover">{{citation|last=Glover|first=Mary R.|title=The Retreat, York: An Early Experiment in the Treatment of Mental Illness|location=York|publisher=Ebor Press|year=1984}}</ref> In 1796, with the help of fellow Quakers and others, he founded the [[York Retreat]], where eventually about 30 patients lived as part of a small community in a quiet country house and engaged in a combination of rest, talk, and manual work. Rejecting medical theories and techniques, the efforts of the York Retreat centered around minimizing restraints and cultivating rationality and moral strength. The entire Tuke family became known as founders of moral treatment.<ref name=Borthwick2001>{{cite journal |last1=Borthwick |first1=Annie |last2=Holman |first2=Chris |last3=Kennard |first3=David |last4=McFetridge |first4=Mark |last5=Messruther |first5=Karen |last6=Wilkes |first6=Jenny |title=The relevance of moral treatment to contemporary mental health care |journal=Journal of Mental Health |volume=10 |issue=4 |pages=427–439 |publisher=Routledge |year=2001 |doi=10.1080/09638230124277}}</ref> |

|||

William Tuke's grandson, [[Samuel Tuke (reformer)|Samuel Tuke]], published an influential work in the early 19th century on the methods of the retreat; Pinel's ''Treatise On Insanity'' had by then been published, and Samuel Tuke translated his term as "moral treatment". Tuke's Retreat became a model throughout the world for humane and moral treatment of patients suffering from mental disorders.<ref name=Borthwick2001/> The York Retreat inspired similar institutions in the United States, most notably the [[Brattleboro Retreat]] and the Hartford Retreat (now [[The Institute of Living]]). |

|||

| ⚫ | Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread into the 19th century. At the [[Lincoln Asylum]] in England, [[Robert Gardiner Hill]], with the support of [[Edward Parker Charlesworth]], pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with — a situation he finally achieved in 1838. In 1839 Sergeant John Adams and Dr. [[John Conolly]] were impressed by the work of Hill, and introduced the method into their [[Hanwell Asylum]], by then the largest in the country |

||

===Phrenology=== |

|||

{{main|Phrenology}} |

|||

[[File:Phrenologie1-157k.png|thumb|right|200x200px|[[William A. F. Browne]] was an influential reformer of the lunatic asylum in the mid-19th century, and an advocate of the new 'science' of [[phrenology]].]] |

|||

Scotland's [[Edinburgh]] medical school of the eighteenth century developed an interest in mental illness, with influential teachers including [[William Cullen]] (1710–1790) and [[Robert Whytt]] (1714–1766) emphasising the clinical importance of psychiatric disorders. In 1816, the phrenologist [[Johann Spurzheim]] (1776–1832) visited Edinburgh and lectured on his craniological and phrenological concepts; the central concepts of the system were that the brain is the organ of the mind and that human behaviour can be usefully understood in neurological rather than philosophical or religious terms. Phrenologists also laid stress on the modularity of mind. |

|||

Some of the medical students, including [[William A. F. Browne]] (1805–1885), responded very positively to this materialist conception of the nervous system and, by implication, of mental disorder. [[George Combe]] (1788–1858), an Edinburgh solicitor, became an unrivalled exponent of phrenological thinking, and his brother, [[Andrew Combe]] (1797–1847), who was later appointed a physician to Queen Victoria, wrote a phrenological treatise entitled ''Observations on Mental Derangement'' (1831). They also founded the [[Edinburgh Phrenological Society]] in 1820. |

|||

===Institutionalization=== |

|||

{{Main|Institutionalization}} |

|||

The modern era of institutionalized provision for the care of the mentally ill, began in the early 19th century with a large state-led effort. Public mental asylums were established in Britain after the passing of the 1808 County Asylums Act. This empowered [[magistrate]]s to build rate-supported asylums in every [[county]] to house the many 'pauper lunatics'. Nine counties first applied, and the first public asylum opened in 1812 in [[Nottinghamshire]]. [[Parliamentary Committee]]s were established to investigate abuses at private madhouses like [[Bethlem Hospital]] - its officers were eventually dismissed and national attention was focused on the routine use of bars, chains and handcuffs and the filthy conditions the inmates lived in. However, it was not until 1828 that the newly appointed [[Commissioners in Lunacy]] were empowered to license and supervise private asylums. |

|||

[[File:Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury by John Collier.jpg|thumb|left|220px|[[Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury|Lord Shaftesbury]], a vigorous campaigner for the reform of lunacy law in England, and the Head of the [[Lunacy Commission]] for 40 years.]] |

|||

The [[Lunacy Act 1845]] was an important landmark in the treatment of the mentally ill, as it explicitly changed the status of [[mental illness|mentally ill]] people to [[patients]] who required treatment. The Act created the [[Lunacy Commission]], headed by [[Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury|Lord Shaftesbury]], to focus on lunacy legislation reform.<ref>Unsworth, Clive."Law and Lunacy in Psychiatry's 'Golden Age'", Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. Vol. 13, No. 4. (Winter, 1993), pp. 482.</ref> The Commission was made up of eleven Metropolitan Commissioners who were required to carry out the provisions of the Act;<ref name="Wright, 1999">Wright, David: "Mental Health Timeline", 1999</ref>{{full|date=November 2014}} the compulsory construction of asylums in every county, with regular inspections on behalf of the [[Home Secretary]]. All asylums were required to have written regulations and to have a resident qualified [[physician]].<ref name="Wright, 1999"/> A national body for asylum superintendents - the ''Medico-Psychological Association'' - was established in 1866 under the Presidency of [[William A. F. Browne]], although the body appeared in an earlier form in 1841.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|pp=34, 41}} |

|||

In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country. [[Édouard Séguin]] developed a systematic approach for training individuals with mental deficiencies,<ref>{{cite book|last1=King|first1=D. Brett|last2=Viney|first2=Wayne|last3=Woody|first3=William Douglas|title=A History of Psychology: Ideas and Context|date=2007|publisher=Allyn & Bacon|isbn=9780205512133|page=214|edition=4}}</ref> and, in 1839, he opened the first school for the severely retarded. His method of treatment was based on the assumption that the mentally deficient did not suffer from disease.<ref>{{cite web|author1=Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica|title=Edouard Seguin (American psychiatrist)|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/532753/Edouard-Seguin|website=Encyclopædia Britannica|date=12 June 2013}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | In the United States, the erection of state asylums began with the first law for the creation of one in New York, passed in 1842. The [[Utica State Hospital]] was opened approximately in 1850 |

||

| ⚫ | At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=34}} By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. However, the idea that mental illness could be ameliorated through institutionalization |

||

===Scientific advances=== |

|||

[[File:Emil Kraepelin2.gif|thumb|right|[[Emil Kraepelin]] studied and promoted ideas of disease classification for mental disorders.]] |

[[File:Emil Kraepelin2.gif|thumb|right|[[Emil Kraepelin]] studied and promoted ideas of disease classification for mental disorders.]] |

||

In the early 1800s, psychiatry made advances in the diagnosis of mental illness by broadening the category of mental disease to include [[mood disorder]]s, in addition to disease level [[delusion]] or ir[[rationality]].<ref name=WCFCD/> The 20th century introduced a new psychiatry into the world, with different perspectives of looking at mental disorders. For Emil Kraepelin, the initial ideas behind biological psychiatry, stating that the different mental disorders are all biological in nature, evolved into a new concept of "nerves", and psychiatry became a rough approximation of neurology and neuropsychiatry.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=114}} Following [[Sigmund Freud]]'s pioneering work, ideas stemming from [[psychoanalytic theory]] also began to take root in psychiatry.<ref name=Shorter145>{{harvnb|Shorter|1997|p=145}}.</ref> The psychoanalytic theory became popular among psychiatrists because it allowed the patients to be treated in private practices instead of warehoused in asylums.<ref name=Shorter145/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The 20th century introduced a new psychiatry into the world. Different perspectives of looking at mental disorders began to be introduced. The career of [[Emil Kraepelin]] reflects the convergence of different disciplines in psychiatry.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=101}} Kraepelin initially was very attracted to psychology and ignored the ideas of anatomical psychiatry.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=101}} Following his appointment to a professorship of psychiatry and his work in a university psychiatric clinic, Kraepelin's interest in pure psychology began to fade and he introduced a plan for a more comprehensive psychiatry.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|pp=102-103}} Kraepelin began to study and promote the ideas of disease classification for mental disorders, an idea introduced by [[Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum]].{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=103}} The initial ideas behind biological psychiatry, stating that the different mental disorders were all biological in nature, evolved into a new concept of "nerves" and psychiatry became a rough approximation of neurology and neuropsychiatry.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=114}} However, Kraepelin was criticized for considering [[schizophrenia]] as a biological illness in the absence of any detectable histologic or anatomic abnormalities.<ref name=Cohen>{{cite book|last=Cohen|first=Bruce|title=Theory and practice of psychiatry|year=2003|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0-19-514937-8|page=221|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=H8ZrAAAAMAAJ}}</ref>{{rp|221}} While Kraepelin tried to find organic causes of mental illness, he adopted many theses of [[Positivism|positivist]] [[medicine]], but he favoured the precision of [[Nosology|nosological]] classification over the indefiniteness of [[Etiology|etiological]] causation as his basic mode of psychiatric explanation.<ref name=Thiher>{{cite book|last=Thiher|first=Allen|title=Revels in Madness: Insanity in Medicine and Literature|year=2000|publisher=University of Michigan Press|isbn=978-0-472-11035-3|page=[http://books.google.com/books?id=G_Ww-9iiKe0C&pg=PT137 228]}}</ref> |

|||

Following [[Sigmund Freud]]'s pioneering work, ideas stemming from [[psychoanalytic theory]] also began to take root in psychiatry.<ref name=Shorter145>{{harvnb|Shorter|1997|p=145}}.</ref> The psychoanalytic theory became popular among psychiatrists because it allowed the patients to be treated in private practices instead of warehoused in asylums.<ref name=Shorter145/> By the 1970s the psychoanalytic school of thought had become marginalized within the field.<ref name=Shorter145/> |

|||

[[File:Acetylcholine.svg|left|thumb|[[Otto Loewi]]'s work led to the identification of the first neurotransmitter, [[acetylcholine]].]] |

[[File:Acetylcholine.svg|left|thumb|[[Otto Loewi]]'s work led to the identification of the first neurotransmitter, [[acetylcholine]].]] |

||

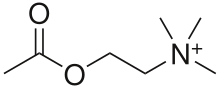

By the 1970s, however, the psychoanalytic school of thought became marginalized within the field.<ref name=Shorter145/>nBiological psychiatry reemerged during this time. [[Psychopharmacology]] became an integral part of psychiatry starting with [[Otto Loewi]]'s discovery of the neuromodulatory properties of [[acetylcholine]]; thus identifying it as the first-known neurotransmitter.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=246}} [[Neuroimaging]] was first utilized as a tool for psychiatry in the 1980s.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=270}} The discovery of [[chlorpromazine]]'s effectiveness in treating [[schizophrenia]] in 1952 revolutionized treatment of the disorder,<ref name="Turner2007">{{cite journal | author = Turner T | title = Unlocking psychosis | journal = Brit J Med | volume = 334 | issue = suppl | pages = s7 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17204765 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94 }}</ref> as did [[lithium carbonate]]'s ability to stabilize mood highs and lows in [[bipolar disorder]] in 1948.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Cade JFJ | title = Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement | url = | journal = Med J Aust | volume = 1949 | issue = 36| pages = 349–352 }}</ref> Psychotherapy was still utilized, but as a treatment for psychosocial issues.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=239}} |

|||

Now genetics are once again thought by some prominent researchers to play a large role in mental illness.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=246}}<ref name=Cloninger>{{cite journal|author=Arnedo J, Svrakic DM, Del Val C, Romero-Zaliz R, Hernández-Cuervo H; Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia Consortium, Fanous AH, Pato MT, Pato CN, de Erausquin GA, Cloninger CR, Zwir I|title=Uncovering the hidden risk architecture of the schizophrenias: confirmation in three independent genome-wide association studies|journal=The American Journal of Psychiatry|volume=172|issue=2|pages=139-53|date=February 2015|pmid=25219520|doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14040435|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25219520}}</ref> The genetic and heritable proportion of the cause of five major psychiatric disorders found in family and twin studies is 81% for schizophrenia, 80% for autism spectrum disorder, 75% for bipolar disorder, 75% for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and 37% for major depressive disorder.<ref name = heritability>{{cite journal|author=Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium|title=Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs|journal=Nature Genetics|volume=45|issue=9|pages=984-995|date=September 2013|doi=10.1038/ng.2711}}</ref> Geneticist [[:de:Benno Müller-Hill|Müller-Hill]] is quoted as saying "Genes are not destiny, they may give an individual a pre-disposition toward a disorder, for example, but that only means they are more likely than others to have it. It (mental illness) is not a certainty.”<ref>{{cite web|last1=Comeau|first1=Sylvain|title=Geneticist Müller-Hill raises spectre of Nazi experiments|url=http://ctr.concordia.ca/2003-04/may_6/14/|website=Concordia's Thursday Report|publisher=Concordia University|date=6 May 2004}}</ref>{{Unreliable medical source|date=November 2014}} Molecular biology opened the door for specific genes contributing to mental disorders to be identified.{{sfn|Shorter|1997|p=246}} |

|||

===Deinstitutionalization=== |

|||

{{Main|Deinstitutionalisation}} |

|||

''[[Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates]]'' (1961), written by [[sociologist]] [[Erving Goffman]],<ref name="Goffman">{{cite book|last=Goffman|first=Erving |title=Asylums: essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates|year=1961|publisher=Anchor Books|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=FqELAQAAIAAJ}}</ref><ref name="Extracts">{{cite web|title=Extracts from Erving Goffman: A Middlesex University resource|url=http://studymore.org.uk/xgof.htm#Asylums|accessdate=8 November 2010|last=Roberts|first=Andrew}}</ref>{{Better source|reason=The source itself looks like one big copyright violation.|date=November 2014}} examined the social situation of mental patients in the hospital.<ref name="Weinstein">{{cite journal |author=Weinstein R. |title=Goffman's Asylums and the Social Situation of Mental Patients |journal=Orthomolecular psychiatry |volume=11 |issue=N 4 |pages=267–274 |year=1982 |pmid= |doi= |url=http://www.orthomolecular.org/library/jom/1982/pdf/1982-v11n04-p267.pdf}}</ref> Based on his [[participant observation]] [[field work]], the book developed the theory of the "[[total institution]]" and the process by which it takes efforts to maintain predictable and regular behavior on the part of both "guard" and "captor". The book suggested that many of the features of such institutions serve the ritual function of ensuring that both classes of people know their function and [[social role]], in other words of "[[Institutionalisation|institutionalizing]]" them. ''Asylums'' was a key text in the development of [[deinstitutionalisation]].<ref name="Mac Suibhne">{{cite journal|last=Mac Suibhne|first=Séamus|title=Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and other Inmates|journal=[[BMJ]]|date=7 October 2009|volume=339|pages=b4109|doi=10.1136/bmj.b4109|url=http://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b4109}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1963, [[President of the United States|US president]] [[John F. Kennedy]] introduced legislation delegating the [[National Institute of Mental Health]] to administer Community Mental Health Centers for those being discharged from state psychiatric hospitals.<ref name=Shorter280>{{harvnb|Shorter|1997|p=280}}.</ref> Later, though, the Community Mental Health Centers focus shifted to providing psychotherapy for those suffering from acute but less serious mental disorders.<ref name=Shorter280/> Ultimately there were no arrangements made for actively following and treating severely mentally ill patients who were being discharged from hospitals |

||

In 1973, psychologist [[David Rosenhan]] published the [[Rosenhan experiment]], a study with results that led to questions about the validity of psychiatric diagnoses.<ref name=Rosenhan>{{cite journal | author = Rosenhan DL | title = On being sane in insane places | journal = Science | volume = 179 | issue = 4070 | pages = 250–258 | year = 1973 | pmid = 4683124 | doi = 10.1126/science.179.4070.250 | url = http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/179/4070/250 }}</ref> Critics such as [[Robert Spitzer (psychiatrist)|Robert Spitzer]] placed doubt on the validity and credibility of the study, but did concede that the consistency of psychiatric diagnoses needed improvement.<ref name=Spitzer2005>{{cite journal | author = Spitzer RL, Lilienfeld SO, Miller MB | title = Rosenhan revisited: The scientific credibility of Lauren Slater's pseudopatient diagnosis study | journal = Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease | volume = 193 | issue = 11 | pages = 734–739 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16260927 | doi = 10.1097/01.nmd.0000185992.16053.5c | url = }}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1963, [[President of the United States|US president]] [[John F. Kennedy]] introduced legislation delegating the [[National Institute of Mental Health]] to administer Community Mental Health Centers for those being discharged from state psychiatric hospitals.<ref name=Shorter280>{{harvnb|Shorter|1997|p=280}}.</ref> Later, though, the Community Mental Health Centers focus shifted to providing psychotherapy for those suffering from acute but less serious mental disorders.<ref name=Shorter280/> Ultimately there were no arrangements made for actively following and treating severely mentally ill patients who were being discharged from hospitals, resulting in a large population of chronically homeless people suffering from mentally illness.<ref name=Shorter280/> |

||

Psychiatry, like most medical specialties has a continuing, significant need for research into its diseases, classifications and treatments.{{sfn|Lyness|1997|p=16}} Psychiatry adopts biology's fundamental belief that disease and health are different elements of an individual's adaptation to an environment.<ref name=Guze130>{{harvnb|Guze|1992|p=130}}.</ref> But psychiatry also recognizes that the environment of the human species is complex and includes physical, cultural, and interpersonal elements.<ref name=Guze130/> In addition to external factors, the [[human brain]] must contain and organize an individual's hopes, fears, desires, fantasies and feelings.<ref name=Guze130/> Psychiatry's difficult task is to bridge the understanding of these factors so that they can be studied both clinically and physiologically.<ref name=Guze130/> |

|||

==Controversy== |

==Controversy== |

||

Revision as of 14:21, 3 June 2015

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the study, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental disorders. These include various affective, behavioural, cognitive and perceptual abnormalities.

Initial psychiatric assessment of a person typically begins with a case history and mental status examination. Psychological tests and physical examinations may be conducted, including on occasion the use of neuroimaging or other neurophysiological techniques. Mental disorders are broadly diagnosed in accordance with criteria listed in diagnostic manuals such as the widely used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association, and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), edited and used by the World Health Organization. The fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) was published in 2013, and its development was expected to be of significant interest to many medical fields.[1]

The combined treatment of psychiatric medication and psychotherapy has become the most common mode of psychiatric treatment in current practice,[2] but current practice also includes widely ranging variety of other modalities. Treatment may be delivered on an inpatient or outpatient basis, depending on the severity of functional impairment or on other aspects of the disorder in question. Research and treatment within psychiatry, as a whole, are conducted on an interdisciplinary basis, sourcing an array of sub-specialties and theoretical approaches.

Etymology

The term "psychiatry" was first coined by the German physician Johann Christian Reil in 1808 and literally means the 'medical treatment of the soul' (psych- "soul" from Ancient Greek psykhē "soul"; -iatry "medical treatment" from Gk. iātrikos "medical" from iāsthai "to heal"). A medical doctor specializing in psychiatry is a psychiatrist. (For a historical overview, see Timeline of psychiatry.)

Theory and focus

"Psychiatry, more than any other branch of medicine, forces its practitioners to wrestle with the nature of evidence, the validity of introspection, problems in communication, and other long-standing philosophical issues" (Guze, 1992, p.4).

Psychiatry refers to a field of medicine focused specifically on the mind, aiming to study, prevent, and treat mental disorders in humans.[5][6][7] It has been described as an intermediary between the world from a social context and the world from the perspective of those who are mentally ill.[8]

People who specialize in psychiatry often differ from most other mental health professionals and physicians in that they must be familiar with both the social and biological sciences.[6] The discipline studies the operations of different organs and body systems as classified by the patient's subjective experiences and the objective physiology of the patient.[9] Psychiatry treats mental disorders, which are conventionally divided into three very general categories: mental illnesses, severe learning disabilities, and personality disorders.[10] While the focus of psychiatry has changed little over time, the diagnostic and treatment processes have evolved dramatically and continue to do so. Since the late 20th century the field of psychiatry has continued to become more biological and less conceptually isolated from other medical fields.[11]

Scope of practice

Though the medical specialty of psychiatry uses research in the field of neuroscience, psychology, medicine, biology, biochemistry, and pharmacology,[12] it has generally been considered a middle ground between neurology and psychology.[13] Unlike other physicians and neurologists, psychiatrists specialize in the doctor–patient relationship and are trained to varying extents in the use of psychotherapy and other therapeutic communication techniques.[13] Psychiatrists also differ from psychologists in that they are physicians and only their residency training (usually 3 to 4 years) is in psychiatry; their undergraduate medical training is identical to all other physicians.[14] Psychiatrists can therefore counsel patients, prescribe medication, order laboratory tests, order neuroimaging, and conduct physical examinations.[15]

Ethics

Like other purveyors of professional ethics, the World Psychiatric Association issues an ethical code to govern the conduct of psychiatrists. The psychiatric code of ethics, first set forth through the Declaration of Hawaii in 1977, has been expanded through a 1983 Vienna update and, in 1996, the broader Madrid Declaration. The code was further revised during the organization's general assembblies in 1999, 2002, 2005, and 2011.[16] The World Psychiatric Association code covers such matters as patient assessment, up-to-date knowledge, the human dignity of incapacitated patients, confidentiality, research ethics, sex selection, euthanasia,[17] organ transplantation, torture,[18][19] the death penalty, media relations, genetics, and ethnic or cultural discrimination.[16]

In establishing such ethical codes, the profession has responded to a number of controversies about the practice of psychiatry, for example, surrounding the use of lobotomy and electroconvulsive therapy. Discredited psychiatrists who operated outside the norms of medical ethics include Harry Bailey, Donald Ewen Cameron, Samuel A. Cartwright, Henry Cotton, and Andrei Snezhnevsky.[20][page needed]

Approaches

Psychiatric illnesses can be conceptualised in a number of different ways. The biomedical approach examines signs and symptoms and compares them with diagnostic criteria. Mental illness can be assessed, conversely, through a narrative which tries to incorporate symptoms into a meaningful life history and to frame them as responses to external conditions. Both approaches are important in the field of psychiatry,[21] but have not sufficiently reconciled to settle controversy over either the selection of a psychiatric paradigm or the specification of psychopathology. The notion of a "biopsychosocial model" is often used to underline the multifactorial nature of clinical impairment.[22][23][24] In this notion the word "model" is not used in a strictly scientific way though.[22] Alternatively, a "biocognitive model" acknowledges the physiological basis for the mind's existence, but identifies cognition as an irreducible and independent realm in which disorder may occur.[22][23][24] The biocognitive approach includes a mentalist etiology and provides a natural dualist (i.e. non-spiritual) revision of the biopsychosocial view, reflecting the efforts of Australian psychiatrist Niall McLaren to bring the discipline into scientific maturity in accordance with the paradigmatic standards of philosopher Thomas Kuhn.[22][23][24]

Once a medical professional diagnoses a patient there are numerous ways that they could choose to treat the patient. Often psychiatrists will develop a treatment strategy that incorporates different facets of different approaches into one. Drug prescriptions are very commonly written to be regimented to patients along with any therapy they receive. There are three major pillars of psychotherapy that treatment strategies are most regularly drawn from. Humanistic psychology attempts to put the "whole" of the patient in perspective; it also focuses on self exploration.[25] Behavioralism is a therapeutic school of thought that elects to focus solely on real and observable events, rather than mining the subconscious. Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, concentrates its dealings on early childhood, irrational drives, the subconscious, and conflict between conscious and subconscious streams.[26]

Subspecialties

Various subspecialties and/or theoretical approaches exist which are related to the field of psychiatry. They include the following:

- Addiction psychiatry; focuses on evaluation and treatment of individuals with alcohol, drug, or other substance-related disorders, and of individuals with dual diagnosis of substance-related and other psychiatric disorders.

- Biological psychiatry; an approach to psychiatry that aims to understand mental disorders in terms of the biological function of the nervous system.

- Child and adolescent psychiatry; the branch of psychiatry that specializes in work with children, teenagers, and their families.

- Community psychiatry; an approach that reflects an inclusive public health perspective and is practiced in community mental health services.[27]

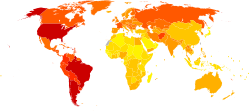

- Cross-cultural psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry concerned with the cultural and ethnic context of mental disorder and psychiatric services.

- Emergency psychiatry; the clinical application of psychiatry in emergency settings.

- Forensic psychiatry; the interface between law and psychiatry.

- Geriatric psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry dealing with the study, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders in humans with old age.

- Liaison psychiatry; the branch of psychiatry that specializes in the interface between other medical specialties and psychiatry.

- Military psychiatry; covers special aspects of psychiatry and mental disorders within the military context.

- Neuropsychiatry; branch of medicine dealing with mental disorders attributable to diseases of the nervous system.

- Social psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry that focuses on the interpersonal and cultural context of mental disorder and mental well-being.

In larger healthcare organizations, both public and private, psychiatrists often serve in senior management roles, where they are responsible for the efficient and effective delivery of mental health services for the organization's constituents. For example, the Chief of Mental Health Services at most VA medical centers is usually a psychiatrist, although psychologists occasionally are selected for the position as well.[citation needed]

In the United States, psychiatry is one of the specialties which qualify for further education and board-certification in pain medicine, palliative medicine, and sleep medicine.

Industry and academia

Practitioners

All physicians can diagnose mental disorders and prescribe treatments utilizing principles of psychiatry. Psychiatrists are either: 1) clinicians who specialize in psychiatry and are certified in treating mental illness;[28] or (2) scientists in the academic field of psychiatry who are qualified as research doctors in this field. Psychiatrists may also go through significant training to conduct psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and cognitive behavioral therapy, but it is their training as physicians that differentiates them from other mental health professionals.[28] There is a significant shortage of psychiatrists in the United States and elsewhere, leading to attempts to extend their services further using telemedicine technologies and other methods.[29]

Research

Psychiatric research is, by its very nature, interdisciplinary; combining social, biological and psychological perspectives in attempt to understand the nature and treatment of mental disorders.[30] Clinical and research psychiatrists study basic and clinical psychiatric topics at research institutions and publish articles in journals.[12][31][32][33] Under the supervision of institutional review boards, psychiatric clinical researchers look at topics such as neuroimaging, genetics, and psychopharmacology in order to enhance diagnostic validity and reliability, to discover new treatment methods, and to classify new mental disorders.[34]

Clinical application

Diagnostic systems

See also Diagnostic classification and rating scales used in psychiatry

Psychiatric diagnoses take place in a wide variety of settings and are performed by many different health professionals. Therefore, the diagnostic procedure may vary greatly based upon these factors. Typically, though, a psychiatric diagnosis utilizes a differential diagnosis procedure where a mental status examination and physical examination is conducted, with pathological, psychopathological or psychosocial histories obtained, and sometimes neuroimages or other neurophysiological measurements are taken, or personality tests or cognitive tests administered.[35][36][37][38][39] In some cases, a brain scan might be used to rule out other medical illnesses, but at this time relying on brain scans alone cannot accurately diagnose a mental illness or tell the risk of getting a mental illness in the future.[40] A few psychiatrists are beginning to utilize genetics during the diagnostic process but on the whole this remains a research topic.[41][42][43]

Diagnostic manuals

Three main diagnostic manuals used to classify mental health conditions are in use today. The ICD-10 is produced and published by the World Health Organization, includes a section on psychiatric conditions, and is used worldwide.[44] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, produced and published by the American Psychiatric Association, is primarily focused on mental health conditions and is the main classification tool in the United States.[45] It is currently in its fifth revised edition and is also used worldwide.[45] The Chinese Society of Psychiatry has also produced a diagnostic manual, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders.[46]

The stated intention of diagnostic manuals is typically to develop replicable and clinically useful categories and criteria, to facilitate consensus and agreed upon standards, whilst being atheoretical as regards etiology.[45][47] However, the categories are nevertheless based on particular psychiatric theories and data; they are broad and often specified by numerous possible combinations of symptoms, and many of the categories overlap in symptomology or typically occur together.[48] While originally intended only as a guide for experienced clinicians trained in its use, the nomenclature is now widely used by clinicians, administrators and insurance companies in many countries.[49]

The DSM has attracted praise for standardizing psychiatric diagnostic categories and criteria. It has also attracted controversy and criticism. Some critics argue that the DSM represents an unscientific system that enshrines the opinions of a few powerful psychiatrists. There are ongoing issues concerning the validity and reliability of the diagnostic categories; the reliance on superficial symptoms; the use of artificial dividing lines between categories and from 'normality'; possible cultural bias; medicalization of human distress and financial conflicts of interest, including with the practice of psychiatrists and with the pharmaceutical industry; political controversies about the inclusion or exclusion of diagnoses from the manual, in general or in regard to specific issues; and the experience of those who are most directly affected by the manual by being diagnosed, including the consumer/survivor movement.[50][51][52][53] The publication of the DSM, with tightly guarded copyrights, now makes APA over $5 million a year, historically adding up to over $100 million.[54]

Treatment

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (May 2009) |

General considerations

Individuals with mental health conditions are commonly referred to as patients but may also be called clients, consumers, or service recipients. They may come under the care of a psychiatric physician or other psychiatric practitioners by various paths, the two most common being self-referral or referral by a primary-care physician. Alternatively, a person may be referred by hospital medical staff, by court order, involuntary commitment, or, in the UK and Australia, by sectioning under a mental health law.

Persons who undergo a psychiatric assessment are evaluated by a psychiatrist for their mental and physical condition. This usually involves interviewing the person and often obtaining information from other sources such as other health and social care professionals, relatives, associates, law enforcement personnel, emergency medical personnel, and psychiatric rating scales. A mental status examination is carried out, and a physical examination is usually performed to establish or exclude other illnesses that may be contributing to the alleged psychiatric problems. A physical examination may also serve to identify any signs of self-harm; this examination is often performed by someone other than the psychiatrist, especially if blood tests and medical imaging are performed.

Like most medications, psychiatric medications can cause adverse effects in patients, and some require ongoing therapeutic drug monitoring, for instance full blood counts serum drug levels, renal function, liver function, and/or thyroid function. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is sometimes administered for serious and disabling conditions, such as those unresponsive to medication. The efficacy[55][56] and adverse effects of psychiatric drugs may vary from patient to patient.

For many years, controversy has surrounded the use of involuntary treatment and use of the term "lack of insight" in describing patients. Mental health laws vary significantly among jurisdictions, but in many cases, involuntary psychiatric treatment is permitted when there is deemed to be a risk to the patient or others due to the patient's illness. Involuntary treatment refers to treatment that occurs based on the treating physician's recommendations without requiring consent from the patient.[57]

Mental health issues such as mood disorders and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders were the most common principle diagnoses for Medicaid super-utilizers in the United States in 2012.[58]

Inpatient treatment

Psychiatric treatments have changed over the past several decades. In the past, psychiatric patients were often hospitalized for six months or more, with some cases involving hospitalization for many years. Today, people receiving psychiatric treatment are more likely to be seen as outpatients. If hospitalization is required, the average hospital stay is around one to two weeks, with only a small number receiving long-term hospitalization.[citation needed]

Psychiatric inpatients are people admitted to a hospital or clinic to receive psychiatric care. Some are admitted involuntarily, perhaps committed to a secure hospital, or in some jurisdictions to a facility within the prison system. In many countries including the USA and Canada, the criteria for involuntary admission vary with local jurisdiction. They may be as broad as having a mental health condition, or as narrow as being an immediate danger to themselves and/or others. Bed availability is often the real determinant of admission decisions to hard pressed public facilities. European Human Rights legislation restricts detention to medically certified cases of mental disorder, and adds a right to timely judicial review of detention.[citation needed]

Patients may be admitted voluntarily if the treating doctor considers that safety isn't compromised by this less restrictive option. Inpatient psychiatric wards may be secure (for those thought to have a particular risk of violence or self-harm) or unlocked/open. Some wards are mixed-sex whilst same-sex wards are increasingly favored to protect women inpatients. Once in the care of a hospital, people are assessed, monitored, and often given medication and care from a multidisciplinary team, which may include physicians, pharmacists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, psychotherapists, psychiatric social workers, occupational therapists and social workers. If a person receiving treatment in a psychiatric hospital is assessed as at particular risk of harming themselves or others, they may be put on constant or intermittent one-to-one supervision, and may be physically restrained or medicated. People on inpatient wards may be allowed leave for periods of time, either accompanied or on their own.[59]

In many developed countries there has been a massive reduction in psychiatric beds since the mid 20th century, with the growth of community care. Standards of inpatient care remain a challenge in some public and private facilities, due to levels of funding, and facilities in developing countries are typically grossly inadequate for the same reason. Even in developed countries, programs in public hospitals vary widely. Some may offer structured activities and therapies offered from many perspectives while others may only have the funding for medicating and monitoring patients. This may be problematic in that the maximum amount of therapeutic work might not actually take place in the hospital setting. This is why hospitals are increasingly used in limited situations and moments of crises where patients are a direct threat to themselves or others. Alternatives to psychiatric hospitals that may actively offer more therapeutic approaches include rehabilitation centers or "rehab" as popularly termed. [citation needed]

Outpatient treatment

Outpatient treatment involves periodic visits to a psychiatrist for consultation in his or her office, or at a community-based outpatient clinic. Initial appointments, at which the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric assessment or evaluation of the patient, are typically 45 to 75 minutes in length. Follow-up appointments are generally shorter in duration, i.e., 15 to 30 minutes, with a focus on making medication adjustments, reviewing potential medication interactions, considering the impact of other medical disorders on the patient's mental and emotional functioning, and counseling patients regarding changes they might make to facilitate healing and remission of symptoms (e.g., exercise, cognitive therapy techniques, sleep hygiene—to name just a few). The frequency with which a psychiatrist sees people in treatment varies widely, from once a week to twice a year, depending on the type, severity and stability of each person's condition, and depending on what the clinician and patient decide would be best.

Increasingly, psychiatrists are limiting their practices to psychopharmacology (prescribing medications), as opposed to previous practice in which a psychiatrist would provide traditional 50-minute psychotherapy sessions, of which psychopharmacology would be a part, but most of the consultation sessions consisted of "talk therapy." This shift began in the early 1980s and accelerated in the 1990s and 2000s.[60] A major reason for this change was the advent of managed care insurance plans, which began to limit reimbursement for psychotherapy sessions provided by psychiatrists. The underlying assumption was that psychopharmacology was at least as effective as psychotherapy, and it could be delivered more efficiently because less time is required for the appointment.[61][62][63][64][65][66] For example, most psychiatrists schedule three or four follow-up appointments per hour, as opposed to seeing one patient per hour in the traditional psychotherapy model.[a]

Because of this shift in practice patterns, psychiatrists often refer patients whom they think would benefit from psychotherapy to other mental health professionals, e.g., clinical social workers and psychologists.[72]

History

The term psychiatry (Greek "ψυχιατρική", psychiatrikē) which comes from the Greek "ψυχή" (psychē: "soul or mind") and "ιατρός" (iatros: "healer") was coined by Johann Christian Reil in 1808.[73][unreliable source?][74]

During the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with psychotic traits, were considered supernatural in origin,[75] a view which existed throughout ancient Greece and Rome.[75] Religious leaders often turned to versions of exorcism to treat mental disorders often utilizing methods that many consider to be cruel and/or barbaric methods.[75]

Specialist hospitals were built in Baghdad in 705 AD,[76] followed by Fes in the early 8th century, and Cairo in 800 AD.[citation needed] Specialist hospitals such as Bethlem Royal Hospital in London were built in medieval Europe from the 13th century to treat mental disorders, but were used only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment.[77]

The beginning of psychiatry as a medical specialty is dated to the middle of the nineteenth century,[78] although its germination can be traced to the late eighteenth century. In the late 17th century, privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. In 1713 the Bethel Hospital Norwich was opened, the first purpose-built asylum in England.[79] In 1656, Louis XIV of France created a public system of hospitals for those suffering from mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.[80]

During the Enlightenment attitudes towards the mentally ill began to change. It came to be viewed as a disorder that required compassionate treatment. In 1758 English physician William Battie wrote his Treatise on Madness on the management of mental disorder. It was a critique aimed particularly at the Bethlem Hospital, where a conservative regime continued to use barbaric custodial treatment. Battie argued for a tailored management of patients entailing cleanliness, good food, fresh air, and distraction from friends and family. He argued that mental disorder originated from dysfunction of the material brain and body rather than the internal workings of the mind.[81][82]

The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor Philippe Pinel and the English Quaker William Tuke.[75] In 1792 Pinel became the chief physician at the Bicêtre Hospital. Patients were allowed to move freely about the hospital grounds, and eventually dark dungeons were replaced with sunny, well-ventilated rooms. Pinel's student and successor, Jean Esquirol (1772–1840), went on to help establish 10 new mental hospitals that operated on the same principles.[83]

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread into the 19th century. At the Lincoln Asylum in England, Robert Gardiner Hill, with the support of Edward Parker Charlesworth, pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with — a situation he finally achieved in 1838. In 1839 Sergeant John Adams and Dr. John Conolly were impressed by the work of Hill, and introduced the method into their Hanwell Asylum, by then the largest in the country.[84][85]

The modern era of institutionalized provision for the care of the mentally ill, began in the early 19th century with a large state-led effort. In England, the Lunacy Act 1845 was an important landmark in the treatment of the mentally ill, as it explicitly changed the status of mentally ill people to patients who required treatment. All asylums were required to have written regulations and to have a resident qualified physician.[86] In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country. In the United States, the erection of state asylums began with the first law for the creation of one in New York, passed in 1842. The Utica State Hospital was opened approximately in 1850. Many state hospitals in the United States were built in the 1850s and 1860s on the Kirkbride Plan, an architectural style meant to have curative effect.[87]

At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums.[88] By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. However, the idea that mental illness could be ameliorated through institutionalization ran into difficulties.[89] Psychiatrists were pressured by an ever increasing patient population,[89] and asylums again becae almost indistinguishable from custodial institutions,[90]

In the early 1800s, psychiatry made advances in the diagnosis of mental illness by broadening the category of mental disease to include mood disorders, in addition to disease level delusion or irrationality.[91] The 20th century introduced a new psychiatry into the world, with different perspectives of looking at mental disorders. For Emil Kraepelin, the initial ideas behind biological psychiatry, stating that the different mental disorders are all biological in nature, evolved into a new concept of "nerves", and psychiatry became a rough approximation of neurology and neuropsychiatry.[92] Following Sigmund Freud's pioneering work, ideas stemming from psychoanalytic theory also began to take root in psychiatry.[93] The psychoanalytic theory became popular among psychiatrists because it allowed the patients to be treated in private practices instead of warehoused in asylums.[93]

By the 1970s, however, the psychoanalytic school of thought became marginalized within the field.[93]nBiological psychiatry reemerged during this time. Psychopharmacology became an integral part of psychiatry starting with Otto Loewi's discovery of the neuromodulatory properties of acetylcholine; thus identifying it as the first-known neurotransmitter.[94] Neuroimaging was first utilized as a tool for psychiatry in the 1980s.[95] The discovery of chlorpromazine's effectiveness in treating schizophrenia in 1952 revolutionized treatment of the disorder,[96] as did lithium carbonate's ability to stabilize mood highs and lows in bipolar disorder in 1948.[97] Psychotherapy was still utilized, but as a treatment for psychosocial issues.[98]

In 1963, US president John F. Kennedy introduced legislation delegating the National Institute of Mental Health to administer Community Mental Health Centers for those being discharged from state psychiatric hospitals.[99] Later, though, the Community Mental Health Centers focus shifted to providing psychotherapy for those suffering from acute but less serious mental disorders.[99] Ultimately there were no arrangements made for actively following and treating severely mentally ill patients who were being discharged from hospitals, resulting in a large population of chronically homeless people suffering from mentally illness.[99]

Controversy

Controversy has often surrounded psychiatry, and the term anti-psychiatry was coined by psychiatrist David Cooper in 1967. The anti-psychiatry message is that psychiatric treatments are ultimately more damaging than helpful to patients, and psychiatry's history involves what may now be seen as dangerous treatments (e.g., electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomy).[100] Some ex-patient groups have become anti-psychiatric, often referring to themselves as "survivors".[100]

See also

- Alienist

- Medical psychology

- Biopsychiatry controversy

- Telepsychiatry

- Telemental health

- Bullying in psychiatry

- Psychiatry organizations

- List of psychiatry journals

References

- ^ Kupfer DJ, Regier DA (2010). "Why all of medicine should care about DSM-5". JAMA. 303 (19): 1974–1975. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.646. PMID 20483976.

- ^ Gabbard GO (2007). "Psychotherapy in psychiatry". International Review of Psychiatry. 19 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1080/09540260601080813. PMID 17365154.

- ^ Rabuzzi, Matthew (November 1997). "Butterfly Etymology". Insects.org.

- ^ James, F.E. (1991). "Psyche" (PDF). Psychiatric Bulletin. 15 (7). Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press: 429–431. doi:10.1192/pb.15.7.429. ISBN 0-88163-257-0. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ Guze 1992, p. 4.

- ^ a b Storrow, H.A. (1969). Outline of Clinical Psychiatry. New York:Appleton-Century-Crofts, p 1. ISBN 978-0-390-85075-1

- ^ Lyness 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Gask 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Guze 1992, p. 131.

- ^ Gask 2004, p. 113.

- ^ Gask 2004, p. 128.

- ^ a b Pietrini P (2003). "Toward a Biochemistry of Mind?". American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1907–1908. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1907. PMID 14594732.

- ^ a b Shorter 1997, p. 326.

- ^ Hauser, Mark J. "Student Information". Psychiatry.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health. (2006, January 31). Information about Mental Illness and the Brain. Retrieved April 19, 2007, from http://science-education.nih.gov/supplements/nih5/Mental/guide/info-mental-c.htm

- ^ a b "Madrid Declaration on Ethical Standards for Psychiatric Practice". World Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ López-Muñoz F, Alamo C, Dudley M, Rubio G, García-García P, Molina JD, Okasha A (2006-12-07). "Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry: Psychiatry and political–institutional abuse from the historical perspective: The ethical lessons of the Nuremberg Trial on their 60th anniversary". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 31 (4). Cecilio Alamoa, Michael Dudleyb, Gabriel Rubioc, Pilar García-Garcíaa, Juan D. Molinad and Ahmed Okasha. Science Direct: 791–806. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.12.007. PMID 17223241.

These practices, in which racial hygiene constituted one of the fundamental principles and euthanasia programmes were the most obvious consequence, violated the majority of known bioethical principles. Psychiatry played a central role in these programmes, and the mentally ill were the principal victims.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gluzman SF (1991). "Abuse of psychiatry: analysis of the guilt of medical personnel". J Med Ethics. 17 (Suppl): 19–20. doi:10.1136/jme.17.Suppl.19. PMC 1378165. PMID 1795363.

Based on the generally accepted definition, we correctly term the utilisation of psychiatry for the punishment of political dissidents as torture.

- ^ Debreu, Gerard (1988). "Part 1: Torture, Psychiatric Abuse, and the Ethics of Medicine". In Corillon, Carol (ed.). Science and Human Rights. National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

Over the past two decades the systematic use of torture and psychiatric abuse have been sanctioned or condoned by more than one-third of the nations in the United Nations, about half of mankind.

- ^ Kirk, Stuart A. (2013). Mad Science: Psychiatric Coercion, Diagnosis, and Drugs. Transaction Publishers.

- ^ Verhulst J, Tucker G (May 1995). "Medical and narrative approaches in psychiatry". Psychiatr Serv. 46 (5): 513–514. PMID 7627683.

- ^ a b c d McLaren N (February 1998). "A critical review of the biopsychosocial model". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 32 (1): 86–92, discussion 93–6. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.1998.00343.x. PMID 9565189.

- ^ a b c McLaren, Niall (2007). Humanizing Madness. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. ISBN 1-932690-39-5.[page needed]

- ^ a b c McLaren, Niall (2009). Humanizing Psychiatry. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. ISBN 1-61599-011-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Humanistic Therapy." CRC Health Group. Web. 29 Mar. 2015. http://www.crchealth.com/types-of-therapy/what-is-humanistic-therapy

- ^ Psychoanalysis | Simply Psychology. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2015, from http://www.simplypsychology.org/psychoanalysis.html

- ^ American Association of Community Psychiatrists About AACP Retrieved on Aug-05-2008

- ^ a b About:Psychology. (Unknown last update) Difference Between Psychologists and Psychiatrists. Retrieved March 25, 2007, from http://psychology.about.com/od/psychotherapy/f/psychvspsych.htm

- ^ Thiele JS, Doarn CR, Shore JH (March 2015). "Locum Tenens and Telepsychiatry: Trends in Psychiatric Care". Telemedicine and e-Health. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0159.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ University of Manchester. (Unknown last update). Research in Psychiatry. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://www.manchester.ac.uk/research/areas/subareas/?a=s&id=44694

- ^ New York State Psychiatric Institute. (2007, March 15). Psychiatric Research Institute New York State. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://nyspi.org/

- ^ Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation. (2007, July 27). Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://www.cprf.ca/

- ^ Elsevier. (2007, October 08). Journal of Psychiatric Research. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/241/description

- ^ Mitchell, J.E.; Crosby, R.D.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Adson, D.E. (2000). Elements of Clinical Research in Psychiatry. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Press. ISBN 978-0-88048-802-0.

- ^ Meyendorf R (1980). "Diagnosis and differential diagnosis in psychiatry and the question of situation referred prognostic diagnosis". Schweizer Archiv Neurol Neurochir Psychiatry für Neurologie, Neurochirurgie et de psychiatrie. 126: 121–134.

- ^ Leigh, H (1983), Psychiatry in the practice of medicine, Menlo Park: Addison-Wesley, pp. 15, 17, 67, ISBN 978-0-201-05456-9

- ^ Lyness 1997, p. 10.

- ^ Hampel H, Teipel SJ, Kötter HU, Horwitz B, Pfluger T, Mager T, Möller HJ, Müller-Spahn F (1997). "Structural magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and research of Alzheimer's disease". Nervenarzt. 68 (5): 365–378. PMID 9280846.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Townsend B.A., Petrella J.R., Doraiswamy P.M. (2002). "The role of neuroimaging in geriatric psychiatry". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 15 (4): 427–432. doi:10.1097/00001504-200207000-00014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NIMH publications (2009) Neuroimaging and Mental Illness

- ^ Krebs MO (2005). "Future contributions on genetics". World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 6: 49–55. doi:10.1080/15622970510030072. PMID 16166024.

- ^ Hensch T, Herold U, Brocke B; Herold, U; Brocke, B (2007). "An electrophysiological endophenotype of hypomanic and hyperthymic personality". Journal of Affective Disorders. 101 (1–3): 13–26. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.018. PMID 17207536.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vonk R, van der Schot AC, Kahn RS, Nolen WA, Drexhage HA (2007). "Is autoimmune thyroiditis part of the genetic vulnerability (or an endophenotype) for bipolar disorder?". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (2): 135–140. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.041. PMID 17141745.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organisation. (1992). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organisation. ISBN 978-92-4-154422-1

- ^ a b c American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6