European Union: Difference between revisions

consistency edit: Slovak Republic --> Slovakia (GDP table) |

|||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

| <small>''millions of [[international dollar]]s''</small> || <small>''international dollars''</small> |

| <small>''millions of [[international dollar]]s''</small> || <small>''international dollars''</small> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| '''European Union''' || '''11,323,496''' || ''' |

| '''European Union''' || '''11,323,496''' || '''24,817''' |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Austria || 251,484 || 30,800 |

| Austria || 251,484 || 30,800 |

||

Revision as of 11:25, 30 January 2005

The European Union or EU is a supranational organisation of European countries, which currently has 25 member states. The Union was established under that name by the Treaty on European Union (commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty) in 1992. However, many aspects of the EU existed before that date through a series of predecessor organisations, dating back to the 1950s.

The European Union's activities cover all policy areas, from health and economic policy to foreign affairs and defence. However, the nature of its powers differs between areas. Depending on the powers transferred to it by its member states, the EU therefore resembles a federation (e.g. monetary affairs, agricultural, trade and environmental policy), a confederation (e.g. in social and economic policy, consumer protection, internal affairs), or an international organisation (e.g. in foreign affairs). A key activity of the EU is the establishment and administration of a common single market, consisting of a customs union, a single currency (adopted by 12 of the 25 member states), a Common Agricultural Policy and a Common Fisheries Policy.

On 29 October 2004, European heads of state signed a treaty establishing the first constitution for the European Union, which is currently awaiting ratification by individual member states.

Status

The European Union is the most powerful regional organisation in existence. As seen above, in certain areas where member states have transferred a degree of sovereignty to the Union the EU begins to resemble a federation or confederation. However, the member states remain the Masters of the Treaties, meaning that the Union does not have the power to transfer additional powers from the member states onto itself, without their agreement. Also the various member states maintain their own policies in key areas of national interest such as foreign relations and defence.

On account of this unique structure, the European Union is perhaps best seen as neither an international organisation nor a confederation or even federation, but rather a sui generis entity.

The current and future status of the European Union is the subject of great political concern within some European Union member states.

Legal base

The legal base of the European Union is a sequence of treaties between its member states. These have been much amended over the years, with each new treaty amending and supplementing earlier ones. The first such treaty was the Treaty of Paris of 1951 which established the European Coal and Steel Community between an original group of six European countries. This treaty has since expired, its functions taken up by subsequent treaties. On the other hand, the Treaty of Rome of 1957 is still in effect, though much amended since then, most notably by the Maastricht treaty of 1992, which first established the European Union under that name. The most recent amendments to the Treaty of Rome were agreed as part of the Treaty of Accession of the 10 new member states, which entered into force on 1 May 2004.

The EU member states have recently agreed to the text of a new constitution that, if ratified by the member states, will become the first official constitution of the EU, replacing all previous treaties with a single document.

If the Constitutional Treaty fails to be ratified by all member states, then it might be necessary to reopen negotiations on it. Most politicians and officials agree that the current pre-Constitution structures are inefficient in the medium term for a union of 25 (and growing) member states. Senior politicians in some member states (notably France) have suggested that if only a few countries fail to ratify the Treaty, then the rest of the Union should proceed without them, possibly creating an "Avant Garde" or Inner Union of more committed member states to proceed with "an ever-deeper, ever-wider union".

See also:

Location of EU institutions

The EU has no official capital and its institutions are divided between several cities. Brussels is the seat of the European Commission and of the Council of Ministers and hosts the committee meetings and some plenary sessions of the European Parliament. Thus it is often regarded as the de facto capital of the EU. Strasbourg is the seat of the European Parliament and is the host for most plenary sessions. The European Court of Justice and the Parliament's secretariat are based in Luxembourg.

Current issues

Major issues facing the European Union at the moment include its enlargement to the south and east (see below), its relationship with the United States of America, the revision of the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact, and the ratification of the European Constitution by member states.

Origins and history

Main article: History of the European Union

Attempts to unify the desparate nations of Europe precede the modern nation states; they have occurred repeatedly throughout the history of the continent since the collapse of the Mediterranean-centred Roman Empire. The Frankish empire of Charlemagne, the Holy Roman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth united large areas under a loose administration for hundreds of years. More recently the 1800s customs union under Napoleon and the 1940s conquests of Nazi Germany had only transitory existence.

Given Europe's heterogeneous collections of languages and cultures, these attempts usually involved military subjugation of unwilling nations, leading to instability and ultimate failure. One of the first proposals for peaceful unification through cooperation and equality of membership, was made by the pacifist Victor Hugo in 1851. Following the catastrophes of the First World War and the Second World War, the impetus for the founding of (what was later to become) the European Union greatly increased, driven by the desire to rebuild Europe and to eliminate the possibility of another such war ever arising. This sentiment eventually led to the formation of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, by West Germany, France, Italy and the Benelux countries.

The first full customs union was originally known as the European Economic Community (informally called the Common Market in the UK), established by the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and implemented on January 1, 1958. This later changed to the European Community which is now the "first pillar" of the European Union. The EU has evolved from a trade body into an economic and political partnership. For more details, please see History of the European Union.

Methods

To accomplish its aims, the European Union attempts to form infrastructure that crosses state borders. Harmonised standards create a larger, more efficient market – member states can form a single customs union without loss of health or safety. For example, states whose people would never agree to eat the same food might still agree on standards for labelling and cleanliness.

The power of the European Union reaches far beyond its borders, because to sell within it, it is beneficial to conform to its standards. Once a non-member country's factories, farmers and merchants conform to EU standards, most of the costs of joining the union have been sunk. At that point, harmonising laws to become a full member creates more wealth (by eliminating the customs costs) with only the tiny investment of actually changing the laws.

Regarding non-economic issues, supporters of the European Union argue that the EU is also a force for peace and democracy. Wars that were a periodic feature of the history of Western Europe have ceased since the formation of the EEC as it then was. In the early 1970s, Greece, Portugal and Spain were all dictatorships, but the business communities in these three countries wanted to be in the EU and this created a strong impetus for democracy there.

In more recent times, the European Union continues to extend its influence to the east. It has accepted several new members that were previously behind the Iron Curtain, and has plans to accept several more in the medium-term. It is hoped that in a similar fashion to the entry of Spain, Portugal and Greece, membership for these states will help cement economic and political stability.

Further eastward expansion also has long-term economic benefits, but the remaining European countries are not viewed as currently suitable for membership, especially the troubled economies of countries further east. Eventually including states that are currently politically unstable will, it is hoped, help deal with the lingering consequences of such problems as the Yugoslav wars, or avoid such conflicts as the Cyprus dispute in the future.

Member states and successive enlargements

Main articles: European Union member states, Enlargement of the European Union, Countries bordering the European Union, Membership criteria.

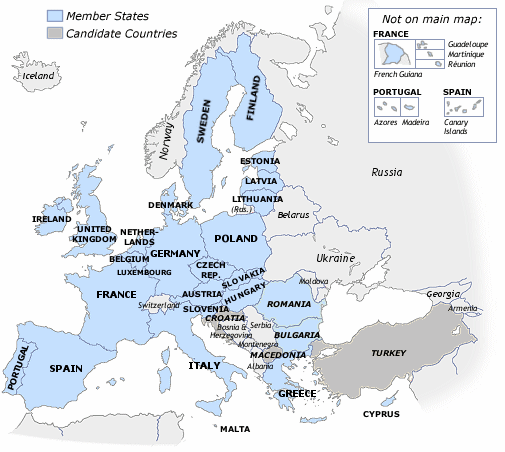

Since 1 May, 2004, the European Union comprises 25 member states. The total area of the 25 member states (2004) of the European Union is 3,892,685 km². Were it a country, it would be the seventh largest in the world by area. The number of EU citizens (all EU member state citizens or subjects, under the terms of the Maastricht treaty) in the 25 member EU is approximately 453 million as of March 2004. This would be the third largest in the world after China and India.

In 1952/1958 the six founding members were: Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and Netherlands. Nineteen further states have since then joined in successive waves of enlargement:

| Year | Countries |

|---|---|

| 1973 | Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom |

| 1981 | Greece |

| 1986 | Portugal and Spain |

| 1995 | Austria, Finland, and Sweden |

| 2004 | Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia |

Notes:

- Greenland, which was granted home rule by Denmark in 1979, left the European Communities in 1985, following a referendum.

- in 1990: the European Community territory and population was enlarged when East Germany reunited with West Germany.

Future members, other countries

The next expansion is set to take place in 2007, with Bulgaria and Romania likely to join at that date. Croatia is also an official candidate, and is likely to join within a similar timescale. Turkey is the only other official candidate, though with a less definitive estimate for an accession date. Further information about future enlargements can be found in the Enlargement of the European Union article.

Many countries, such as Norway and Switzerland, while not being member states have special agreements with the union. (See the third country relationships with the EU article). In addition, most of the EFTA-members (the European Free Trade Association) are parties to the EEA-treaty (the European Economic Area), which means that these countries are participants in the single market.

Status of overseas territories

Some areas have connections or associations to EU member states through a colonial past, cultural links, or geographic placement. For the status in relation to the EU, of Greenland, the Isle of Man, the Azores and Madeira, amongst others, see the article on Special member state territories and their relations with the EU.

Economic status

Currently (January 2005) the EU, considered as a unit, has the largest economy in the world, with a 2004 GDP of 8.639·10¹² euro (or 11.323·10¹² USD at the exchange rate of $US 1.31 per euro on January 11, 2005 [see table]). The United States, by comparison, has the largest GDP of a single country — 11.175·10¹² dollars (or 8.525·10¹² euro). [1] The European Union continues to enjoy a significant trade surplus. However, as of 2004 the European Union has been suffering stagnant economic growth and high unemployment (averaged across the Union).

The EU economy is expected to grow further over the next decade as more countries join the union - especially considering that the new States are usually poorer than the EU average, and hence the expected fast GDP growth will help achieve the dynamic of the united Europe. However, GDP per capita of the whole Union will fall over the short-term. In the long-term, the EU's economy suffers from significant demographic challenges, with a below-replacement birth rate.

Standard of living

Below is a table and two graphs showing, respectively, the GDP (PPP) and the GDP (PPP) per capita of each of the 25 member states, and the EU average. This can be used as a rough gauge to the relative standards of living among member states. The data set is from the year 2004 (graphs from 2003 data).

| Country | GDP (PPP) | GDP (PPP) per capita |

|---|---|---|

| millions of international dollars | international dollars | |

| European Union | 11,323,496 | 24,817 |

| Austria | 251,484 | 30,800 |

| Belgium | 294,628 | 28,700 |

| Cyprus | 15,436 | 19,200 |

| Czech Republic | 166,134 | 16,300 |

| Denmark | 173,339 | 32,100 |

| Estonia | 18,181 | 13,100 |

| Finland | 145,913 | 28,000 |

| France | 1,671,100 | 27,000 |

| Germany | 2,318,114 | 28,000 |

| Greece | 215,983 | 19,600 |

| Hungary | 150,487 | 15,300 |

| Ireland | 144,330 | 35,900 |

| Italy | 1,582,060 | 27,500 |

| Latvia | 24,336 | 10,400 |

| Lithuania | 41,099 | 11,900 |

| Luxembourg | 28,123 | 61,800 |

| Malta | 7,894 | 20,100 |

| Netherlands | 466,585 | 28,600 |

| Poland | 443,727 | 11,400 |

| Portugal | 188,206 | 18,400 |

| Slovakia | 72,475 | 14,100 |

| Slovenia | 75,990 | 20,500 |

| Spain | 939,153 | 22,800 |

| Sweden | 255,373 | 28,300 |

| United Kingdom | 1,665,013 | 27,800 |

*Data from IMF web sites: 2004 GDP PPP, 2004 per capita GDP PPP.

While the per-capita GDP of the European Union is high compared to the world average, it's lower than that of the United States, which had a per-capita GDP of USD 38,031 in 2004. [2]

Structure

The European Union Law comprises a large number of overlapping legal and institutional structures. This is a result of it being defined by successive international treaties. In recent years, considerable efforts have been made to consolidate and simplify the treaties, culminating with the final draft of the Constitution of Europe.

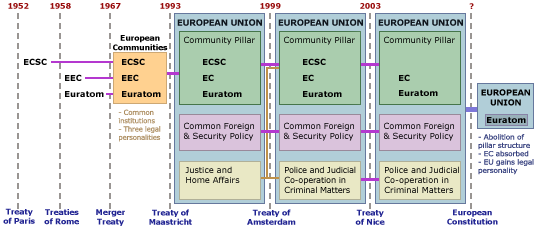

The role of the European Community within the Union

The term European Community (or Communities) was used for the group of members prior to the establishment of the European Union. At present, the term continues to have significance, but in a different context. The "European Community" is one of the three pillars of the European Union, being both the most important pillar and the only one to operate primarily through supranational institutions. The other two pillars – Common Foreign and Security Policy, and Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters, are looser intergovernmental groupings. Confusingly, these latter two concepts are increasingly administered by the Community (as they are built up from mere concepts to actual practice).

What most people think of as the European Union is essentially the European Community. The Community is an actual body, including the European institutions (European Parliament, Council of the European Union, European Commission), whilst the European Union is a less tangible grouping of institutions and agreements.

|

| Evolution of the structures of the European Union. |

Institutional framework

The European Union has several institutions:

- The European Parliament (732 members)

- The Council of the European Union (or 'Council of Ministers') (25 members)

- The European Commission (25 members)

- The European Court of Justice (incorporating the Court of First Instance) (15 judges)

- The European Court of Auditors (25 members)

The European Council (25 members) is not an institution, but a "quasi-institution".

There are several financial bodies:

- European Central Bank (which alongside the national Central Banks, composes the European System of Central Banks)

- European Investment Bank (including the European Investment Fund)

The treaties have also established several advisory committees to the institutions:

- Committee of the Regions, advising on regional issues.

- Economic and Social Committee, advising on economic and social (principally relations between workers and employers)

- Political and Security Committee, established in the context of the Common Foreign and Security Policy, monitoring and advising on international issues of global security.

There is also a great number of bodies which were established by secondary legislation (i.e. not by the treaties) in order to implement particular policies. These are the agencies of the European Union. Some of these are the European Environment Agency, the European Aviation Safety Agency and the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market. In the context of the third pillar (Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters), Europol and Eurojust have been created.

Lastly, the European Ombudsman watches for abuses of power by EU institutions.

Intergovernmentalism and supranationalism

A basic tension exists within the European Union between intergovernmentalism and supranationalism. Intergovernmentalism is a method of decision-making in international organisations where power is possessed by the member-states and decisions are made by unanimity. Independent appointees of the governments or elected representatives have solely advisory or implementational functions. Intergovernmentalism is used by most international organisations today.

An alternative method of decision-making in international organisations is supranationalism. In supranationalism power is held by independent appointed officials or by representatives elected by the legislatures or people of the member states. Member-state governments still have power, but they must share this power with other actors. Furthermore, decisions are made by majority votes, hence it is possible for a member-state to be forced by the other member-states to implement a decision against its will.

Some forces in European Union politics favour the intergovernmental approach, while others favour the supranational path. Supporters of supranationalism argue that it allows integration to proceed at a faster pace than would otherwise be possible. Where decisions must be made by governments acting unanimously, decisions can take years to make, if they are ever made. Supporters of intergovernmentalism argue that supranationalism is a threat to national sovereignty, and to democracy, claiming that only national governments can possess the necessary democratic legitimacy. Intergovernmentalism has historically been favoured by France, and by more Eurosceptic nations such as Britain, Denmark and Estonia; while more integrationist nations such as Belgium, Germany, and Italy have tended to prefer the supranational approach.

The European Union attempts to strike a balance between two approaches. This balance however is complex, resulting in the often labyrinthine complexity of its decision-making procedures.

Starting in March 2002, a Convention on the Future of Europe again looked at this balance, among other things, and proposed changes. These changes were discussed at an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) in May 2004 and agreement reached on a Constitutional Treaty, which will require ratification by each of the member states.

Supranationalism is closely related to the intergovernmentalist vs. neofunctionalist debate. This is a debate concering why the process of integration has taken place at all. Intergovernmentalists argue that the process of EU integration is a result of tough bargaining between states. Neofunctionalism, on the other hand, argues that the supranational institutions themselves have been a driving force behind integration. For further information on this see the page on Neofunctionalism.

Main policies

As the changing name of the European Union (from European Economic Community to European Community to European Union) suggests, it has evolved over time from a primarily economic union to an increasingly political one. This trend is highlighted by the increasing number of policy areas that fall within EU competence: political power has tended to shift upwards from the member states to the EU.

This picture of increasing centralisation is counter-balanced by two points.

First, some member states have a domestic tradition of strong regional government. This has led to an increased focus on regional policy and the European regions. A Committee of the Regions was established as part of the Treaty of Maastricht.

Second, EU policy areas cover a number of different forms of co-operation.

- Autonomous decision making: member states have granted the European Commission power to issue decisions in certain areas such as competition law, State Aid control and liberalisation.

- Harmonisation: member state laws are harmonised through the EU legislative process, which involves the European Commission, European Parliament and Council of the European Union. As a result of this European Union Law is increasingly present in the systems of the member states.

- Co-operation: member states, meeting as the Council of the European Union agree to co-operate and co-ordinate their domestic policies.

The tension between EU and national (or sub-national) competence is an enduring one in the development of the European Union. (See also Intergovernmentalism vs. Supranationalism (above), Euroscepticism.)

All prospective members must enact legislation in order to bring them into line with the common European legal framework, known as the Acquis Communautaire. (See also European Free Trade Association (EFTA), European Economic Area (EEA) and Single European Sky).

Single market

Internal aspects

- Free trade of goods and services among member states (an aim further extended to three of the four EFTA states by the European Economic Area, EEA)

- A common EU competition law controlling anti-competitive activities of companies (through antitrust law and merger control) and member states (through the State Aids regime).

- The Schengen treaty allowed removal of internal border controls and harmonisation of external controls between its member states. This excludes the UK and Ireland, which have derogations, but includes the non-EU members Iceland and Norway.

- Freedom for citizens of its member states to live and work anywhere within the EU, provided they can support themselves (also extended to the other EEA states).

- Free movement of capital between member states (and other EEA states).

- Harmonisation of government regulations, corporations law and trademark registrations.

- A single currency, the Euro (excluding the UK, and Denmark, which have derogations). Sweden, although not having a specific opt-out clause, has not joined the ERM II, voluntarily excluding itself from the monetary union.

- A large amount of environmental policy co-ordination throughout the Union.

- A Common Agricultural Policy and a Common Fisheries Policy.

- Common system of indirect taxation, the VAT, as well as common customs duties and excises on various products.

- Funding for the development of disadvantaged regions (structural and cohesion funds).

- Funding for research.

External aspects

- A common external customs tariff, and a common position in international trade negotiations.

- Funding for programmes in candidate countries and other Eastern European countries, as well as aid to many developing countries.

Co-operation and harmonisation in other areas

- Freedom for its citizens to vote in local government and European Parliament elections in any member state.

- Co-operation in criminal matters, including sharing of intelligence (through EUROPOL and the Schengen Information System), agreement on common definition of criminal offences and expedited extradition procedures.

- A common foreign policy as a future objective, however this has some way to go before being realised. The divisions between the member states (in the letter of eight) and then-future members (in the Vilnius letter) during the run up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq highlights just how far off this objective could be before it becomes a reality.

- A common security policy as an objective, including the creation of a 60,000-member European Rapid Reaction Force for peacekeeping purposes, an EU military staff and an EU satellite centre (for intelligence purposes).

- Common policy on asylum and immigration.

- Common funding of research and technological development, through four-year Framework Programmes for Research and Technological Development. The Sixth Framework Programme is running from 2002 to 2006.

See also

- Lists

- List of European Union-related topics

- Category:European Union (hierachical list of all EU articles)

- Largest cities of the European Union by population

Partial bibliography

- Europe Recast: A History of European Union by Desmond Dinan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) ISBN 0333987349

- The Great Deception: The Secret History of the European Union by Christopher Booker, Richard North (Continuum International Publishing Group - Academi, 2003) ISBN 0826471056

- Understanding the European Union 2nd ed by John McCormick (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002) ISBN 033394867X

- The Institutions of the European Union edited by John Peterson, Michael Shackleton (Oxford University Press, 2002) ISBN 0198700520

- The Government and Politics of the European Union by Neill Nugent (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002) ISBN 0333984617

- The European Union: A Very Short Introduction by John Pinder (Oxford, 2001) ISBN

- This Blessed Plot: Britain and Europe from Churchill to Blair by Hugo Young (Macmillan, 1998) ISBN 0333579925

External links

Official EU website, europa.eu.int, in the official languages. Some subpages:

- European Commission - Maps of Europe

- Press conferences and speech audio (MP3 and RealAudio).

- Green Paper on a numbering policy for telecommunications (+3 country call code proposal)

- EU Policy on China

Other sites

- CIA World Factbook entry

- EurActiv.com Independent media portal dedicated to EU affairs

- EU in the USA - EU delegation to the US

- Dadalos, International UNESCO Education Server for Civic, Peace and Human Rights Education: Basic Course on the EU

- EU Observer - News website focusing on the EU

- Euronews - Multilingual public TV news channel run by ITN

- EU News - European Union News

- BBC News: Inside Europe guide to the changing face of the EU

- Guardian Unlimited Special Report: European Union guide and ongoing news

- LookSmart - European Union directory category

- Open Directory Project - European Union directory category

- Yahoo - European Union directory category