Ciclosporin: Difference between revisions

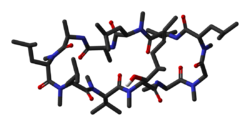

Elbreapoly (talk | contribs) Changed ciclosporin image. This version is higher-resolution and abandons the linear-structure format with two very long bonds to create the cyclic structure. |

Elbreapoly (talk | contribs) Changed IUPAC name to be correct. The former entry listed amino acids as subunits and thus did not follow protocol. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Drugbox| |

{{Drugbox| |

||

|IUPAC_name = (''E'')-14,17,26,32-tetrabutyl-5-ethyl-8-(1-hydroxy-2-methylhex-4-enyl)-1,3,9,12,15,18,20,23,27-nonamethyl-11,29-dipropyl-1,3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27,30-undecaazacyclodotriacontan-2,4,7,10,13,16,19,22,25,28,31-undecaone |

|||

|IUPAC_name = <nowiki>[R-[[R*,R*-(E)]]-cyclic(L-alanyl- D-alanyl-N-methyl-L-leucyl- N-methyl-L-leucyl-N-methyl- L-valyl-3-hydroxy-N,4-dimethyl- L-2-amino-6-octenoyl-L-α-amino- butyryl-N-methylglycyl-N-methyl- L-leucyl-L-valyl-N-methyl-L-leucyl)</nowiki> |

|||

| image=ciclosporin2.png |

| image=ciclosporin2.png |

||

| width = 250 |

| width = 250 |

||

Revision as of 00:54, 26 April 2008

| File:Ciclosporin2.png | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral, IV, ophthalmic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | variable |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | variable (about 24 hours) |

| Excretion | biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.119.569 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C62H111N11O12 |

| Molar mass | 1202.61 g·mol−1 |

Ciclosporin (Template:PronEng), cyclosporine (USAN) or cyclosporin (former BAN), is an immunosuppressant drug widely used in post-allogeneic organ transplant to reduce the activity of the patient's immune system and so the risk of organ rejection. It has been studied in transplants of skin, heart, kidney, lung, pancreas, bone marrow and small intestine. Initially isolated from a Norwegian soil sample, Ciclosporin A, the main form of the drug, is a cyclic nonribosomal peptide of 11 amino acids (an undecapeptide) produced by the fungus Tolypocladium inflatum Gams, and contains D-amino acids, which are rarely encountered in nature.[2]

Indications

The immuno-suppressive effect of cyclosporin was discovered on January 31, 1972, by employees of Sandoz (now Novartis) in Basel, Switzerland, in a screening test on immune-suppression designed and implemented by Dr.Hartmann F. Stähelin, M.D. The success of Ciclosporin A in preventing organ rejection was shown in liver transplants performed by Dr. Thomas Starzl at the University of Pittsburgh hospital. The first patient, on March 9, 1980, was a 28-year-old woman.[3] Ciclosporin was subsequently approved for use in 1983.

Apart from in transplant medicine, cyclosporin is also used in psoriasis, severe atopic dermatitis and infrequently in rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases, although it is only used in severe cases. It has been investigated for use in many other autoimmune disorders. Cyclosporin has also been used to help treat patients with ulcerative colitis who do not respond to treatment with steroids.[4] This drug is also used as a treatment of posterior or intermediate uveitis with non-infective etiology.

Cyclosporin A has been investigated as a possible neuroprotective agent in conditions such as traumatic brain injury, and has been shown in animal experiments to reduce brain damage associated with injury.[5] Cyclosporin A blocks the formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, which has been found to cause much of the damage associated with head injury and neurodegenerative diseases.

Mode of action

Ciclosporin is thought to bind to the cytosolic protein cyclophilin (immunophilin) of immunocompetent lymphocytes, especially T-lymphocytes. This complex of ciclosporin and cyclophylin inhibits calcineurin, which under normal circumstances is responsible for activating the transcription of interleukin-2. It also inhibits lymphokine production and interleukin release and therefore leads to a reduced function of effector T-cells. It does not affect cytostatic activity.

It also has an effect on mitochondria. Ciclosporin A prevents the mitochondrial PT pore from opening, thus inhibiting cytochrome c release, a potent apoptotic stimulation factor. However, this is not the primary mode of action for clinical use but rather an important effect for research on apoptosis.

Adverse effects and interactions

Treatment may be associated with a number of potentially serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and adverse drug interactions. Ciclosporin interacts with a wide variety of other drugs and other substances including grapefruit juice, although there have been studies into the use of grapefruit juice to increase the blood level of ciclosporin.

ADRs can include gum hyperplasia, convulsions, peptic ulcers, pancreatitis, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, breathing difficulties, numbness and tingling, pruritus, high blood pressure, potassium retention and possibly hyperkalemia, kidney and liver dysfunction (nephrotoxicity & hepatotoxicity), and obviously an increased vulnerability to opportunistic fungal and viral infections.

An alternate form of the drug, ciclosporin G (OG37-324), has been found to be much less nephrotoxic than the standard ciclosporin A.[6] Ciclosporin G (Mol. mass 1217) differs from ciclosporin A in the amino acid 2 position, where an L-nor-valine replaces the α-aminobutyric acid.[7]

Formulations

The drug is marketed by Novartis under the brand names Sandimmune, the original formulation, and Neoral for the newer microemulsion formulation. Generic ciclosporin preparations have been marketed under various trade names including Cicloral (Sandoz/Hexal) and Gengraf (Abbott). Since 2002 a topical emulsion of ciclosporin for treating keratoconjunctivitis sicca has been marketed under the trade name Restasis. Annual sales of ciclosporin are around $1 billion.

The drug is also available in a dog preparation manufactured by Novartis called Atopica. Atopica is indicated for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. Unlike the human form of the drug, the lower doses used in dogs mean the drug acts as an immuno-modulator and has fewer side effects than in man. The benefits of using this product include the reduced need for concurrent therapies to bring the condition under control.

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Borel JF (2002). "History of the discovery of cyclosporin and of its early pharmacological development". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 114 (12): 433–7. PMID 12422576.

Some sources list the fungus under an alternative species name Hypocladium inflatum gams such as Pritchard and Sneader in 2005:

* Pritchard DI (2005). "Sourcing a chemical succession for cyclosporin from parasites and human pathogens". Drug Discov. Today. 10 (10): 688–91. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03395-7. PMID 15896681.

* "Ciclosporin". Drug Discovery - A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. pp 298-299 (refs. page 315).{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

However, the name, Tolypocladium inflatum Gams, also appears in several other articles including in a 2001 online publication by Harriet Upton entitled "Origin of drugs in current use: the cyclosporin story" (retrieved June 19, 2005). Mark Plotkin states in his book Medicine Quest, Penguin Books 2001, pages 46-47, that in 1996 mycology researcher Kathie Hodge found that it is in fact a species of Cordyceps. - ^ Starzl TE, Klintmalm GB, Porter KA, Iwatsuki S, Schröter GP (1981). "Liver transplantation with use of cyclosporin a and prednisone". N. Engl. J. Med. 305 (5): 266–9. PMID 7017414.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A; et al. (1994). "Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy". N. Engl. J. Med. 330 (26): 1841–5. PMID 8196726.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sullivan PG, Thompson M, Scheff SW (2000). "Continuous infusion of cyclosporin A postinjury significantly ameliorates cortical damage following traumatic brain injury". Exp. Neurol. 161 (2): 631–7. doi:10.1006/exnr.1999.7282. PMID 10686082.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Henry ML, Elkhammas EA, Davies EA, Ferguson RM (1995). "A clinical trial of cyclosporine G in cadaveric renal transplantation". Pediatr. Nephrol. 9 Suppl: S49-51. PMID 7492487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Calne RY, White DJ, Thiru S, Rolles K, Drakopoulos S, Jamieson NV (1985). "Cyclosporin G: immunosuppressive effect in dogs with renal allografts". Lancet. 1 (8441): 1342. PMID 2860538.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

See also

- Cremophor EL ( Additive in Sandimmune )

- Castor oil ( Additive in Sandimmune )