Trinity College, Cambridge: Difference between revisions

| Line 169: | Line 169: | ||

===Admissions=== |

===Admissions=== |

||

Currently, about 50% of Trinity's undergraduates attended independent schools. In 2006 it accepted a smaller proportion of students from state schools (39%) than any other Cambridge college, and on a rolling three-year average it has admitted a smaller proportion of state school pupils (42%) than any other college at either Cambridge or Oxford.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/reporter/2006-07/special/11/table7.pdf |title=Cambridge 2005/2006 admissions statistics by college |access-date=28 February 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/reporter/2005-06/special/11/table7.pdf |title=Cambridge 2004/2005 admissions statistics by college |access-date=28 February 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ox.ac.uk/about_the_university/facts_and_figures/undergraduate_admissions_statistics/school_type.html|title=Oxford 3-year average admissions statistics by college|access-date=1 August 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130802013322/http://www.ox.ac.uk/about_the_university/facts_and_figures/undergraduate_admissions_statistics/school_type.html|archive-date=2 August 2013}}</ref> |

Currently{{when}}, about 50% of Trinity's undergraduates attended independent schools. In 2006 it accepted a smaller proportion of students from state schools (39%) than any other Cambridge college, and on a rolling three-year average it has admitted a smaller proportion of state school pupils (42%) than any other college at either Cambridge or Oxford.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/reporter/2006-07/special/11/table7.pdf |title=Cambridge 2005/2006 admissions statistics by college |access-date=28 February 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/reporter/2005-06/special/11/table7.pdf |title=Cambridge 2004/2005 admissions statistics by college |access-date=28 February 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ox.ac.uk/about_the_university/facts_and_figures/undergraduate_admissions_statistics/school_type.html|title=Oxford 3-year average admissions statistics by college|access-date=1 August 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130802013322/http://www.ox.ac.uk/about_the_university/facts_and_figures/undergraduate_admissions_statistics/school_type.html|archive-date=2 August 2013}}</ref> |

||

According to the ''[[The Good Schools Guide|Good Schools Guide]]'', about 7% of British school-age students attend private schools, although this figure refers to students in all school years – a higher proportion attend private schools in their final two years before university. Trinity states that it disregards what type of school its applicants attend, and accepts students solely on the basis of their academic prospects. |

According to the ''[[The Good Schools Guide|Good Schools Guide]]'', about 7% of British school-age students attend private schools, although this figure refers to students in all school years – a higher proportion attend private schools in their final two years before university. Trinity states that it disregards what type of school its applicants attend, and accepts students solely on the basis of their academic prospects. |

||

Revision as of 19:20, 10 October 2021

| Trinity College | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Cambridge | ||||||||||||

Trinity College Great Court

| ||||||||||||

Coat of arms of the Trinity College Arms: Argent, a chevron between three roses gules barbed and seeded proper and on a chief gules a lion passant gardant between two closed books all Or | ||||||||||||

| Location | Trinity Street (map) | |||||||||||

| Full name | The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity within the Town and University of Cambridge of King Henry the Eighth's Foundation | |||||||||||

| Motto | Virtus Vera Nobilitas[1] (Latin) | |||||||||||

| Motto in English | Virtue is true nobility | |||||||||||

| Founder | Henry VIII of England | |||||||||||

| Established | 1546 | |||||||||||

| Named after | The Holy Trinity | |||||||||||

| Previous names | King's Hall and Michaelhouse (until merged in 1546) | |||||||||||

| Sister college | Christ Church, Oxford | |||||||||||

| Master | Dame Sally Davies | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 730 | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 350 | |||||||||||

| Senior tutor | Catherine Barnard | |||||||||||

| Endowment | £1.2B (2019)[2] | |||||||||||

| Website | trin | |||||||||||

| Students' union | www | |||||||||||

| BA society | basociety | |||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII. Trinity is one of the oldest and largest colleges in Cambridge,[3] with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. Trinity has some of the most distinctive architecture within Cambridge, with its Great Court reputed to be the largest enclosed courtyard in Europe.[4] Academically, Trinity performs exceptionally as measured by the Tompkins Table (the annual unofficial league table of Cambridge colleges), coming in first from 2011 to 2017, with 42.5% of undergraduates obtaining a first class result in 2019.[5]

Members of Trinity have won 34 Nobel Prizes[6] out of the 121 won by members of Cambridge University, the highest number of any college at either Oxford or Cambridge. Members of the college have won five Fields Medals, one Turing Award and one Abel Prize.[7] Trinity alumni include the father of the scientific method (or empiricism) Francis Bacon, six British prime ministers (the highest of any Cambridge college), physicists Isaac Newton, James Clerk Maxwell, Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr, mathematicians Srinivasa Ramanujan and Charles Babbage, poets Lord Byron and Lord Tennyson, English jurist Edward Coke, writers Vladimir Nabokov and A. A. Milne, historians Lord Macaulay and G. M. Trevelyan and philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell (whom it expelled before reaccepting).

Two members of the British royal family have studied at Trinity and been awarded degrees: Prince William of Gloucester and Edinburgh, who gained an MA in 1790, and Prince Charles, who was awarded a lower second class BA in 1970. Other royal family members that have studied at Trinity without obtaining degrees include King Edward VII, King George VI, and Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester.

Trinity has many college societies, including the Trinity Mathematical Society, which is the oldest mathematical university society in the United Kingdom, and the First and Third Trinity Boat Club, its rowing club, which gives its name to the college's May Ball. Along with Christ's, Jesus, King's and St John's colleges, it has also provided several of the well known members of the Apostles, an intellectual secret society. In 1848, Trinity hosted the meeting at which Cambridge undergraduates representing public schools such as Westminster codified the early rules of football, known as the Cambridge Rules.[8] Trinity's sister college in Oxford is Christ Church. Like that college, Trinity has been linked with Westminster School since the school's re-foundation in 1560, and its Master is an ex officio governor of the school.[9] Trinity also maintains a significant connection with Whitgift School in Croydon, as John Whitgift, the founder of Whitgift School, was the master of Trinity from 1561 to 1564.

With around 730 undergraduates, 300 graduates, and over 180 fellows, Trinity is the largest college in either of the Oxbridge universities by number of undergraduates.

History

Foundation

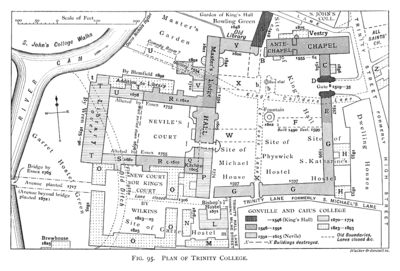

The college was founded by Henry VIII in 1546, from the merger of two existing colleges: Michaelhouse (founded by Hervey de Stanton in 1324), and King's Hall (established by Edward II in 1317 and refounded by Edward III in 1337). At the time, Henry had been seizing (Catholic) church lands from abbeys and monasteries. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge, being both religious institutions and quite rich, expected to be next in line. The King duly passed an Act of Parliament that allowed him to suppress (and confiscate the property of) any college he wished. The universities used their contacts to plead with his sixth wife, Catherine Parr. The Queen persuaded her husband not to close them down, but to create a new college. The king did not want to use royal funds, so he instead combined two colleges (King's Hall and Michaelhouse) and seven hostels namely Physwick (formerly part of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge), Gregory's, Ovyng's, Catherine's, Garratt, Margaret's and Tyler's, to form Trinity.

Nevile's expansion

The monastic lands granted by Henry VIII were not on their own sufficient to ensure Trinity's eventual rise. In terms of architecture and royal association, it was not until the Mastership of Thomas Nevile (1593–1615) that Trinity assumed both its spaciousness and its association with the governing class that distinguished it since the Civil War. In its infancy Trinity had owed a great deal to its neighbouring college of St John's: in the exaggerated words of Roger Ascham, Trinity was little more than a colonia deducta[clarification needed].[10] Its first four Masters were educated at St John's, and it took until around 1575 for the two colleges' application numbers to draw even, a position in which they have remained since the Civil War. Nevile's building campaign drove the college into debt from which it only surfaced in the 1640s, and the Mastership of Richard Bentley adversely affected applications and finances.[10] Bentley himself was notorious for the construction of a hugely expensive staircase in the Master's Lodge, and for his repeated refusals to step down despite pleas from the Fellows.

Most of the Trinity's major buildings date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Thomas Nevile, who became Master of Trinity in 1593, rebuilt and redesigned much of the college. This work included the enlargement and completion of Great Court, and the construction of Nevile's Court between Great Court and the river Cam. Nevile's Court was completed in the late 17th century with the Wren Library, designed by Christopher Wren.

Modern day

In the 20th century, Trinity College, St John's College and King's College were for decades the main recruiting grounds for the Cambridge Apostles, an elite, intellectual secret society.

In 2011, the John Templeton Foundation awarded Trinity College's Master, the astrophysicist Martin Rees, its controversial million-pound[11] Templeton Prize, for "affirming life's spiritual dimension".

Trinity is the richest Oxbridge college with a landholding alone worth £800 million.[12] For comparison, the second richest college in Cambridge (St. John's) has estimated assets of around £780 million, and the richest college in Oxford (St. John's) has about £600 million.[13] In 2005, Trinity's annual rental income from its properties was reported to be in excess of £20 million.[citation needed]

The college owns:

- 3400 acres (14 km2) housing facilities at the Port of Felixstowe, Britain's busiest container port

- the Cambridge Science Park[14]

- the O2 Arena in London (formerly the Millennium Dome)[15]

In 2018, Trinity revealed that it had investments totalling £9.1M in companies involved in oil and gas production, exploration and refinement. These included holdings of £1.2M in Royal Dutch Shell, £1.7M in Exxon Mobil and £1M in Chevron.[16] On 17 February 2020, protestors from the campaign group Extinction Rebellion dug up the front lawn of Trinity College to protest against the College's investments in fossil fuels and its negotiations to sell off a farm in Suffolk that was to be turned into a lorry park.[17]

In 2019, Trinity confirmed its plan to withdraw from the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), the main pre-1992 UK University pension provider.[18] In response, more than 500 Cambridge academics signed an open letter undertaking to "refuse to supervise Trinity students or to engage in other discretionary work in support of Trinity’s teaching and research activities".[19]

Legends

Lord Byron purportedly kept a pet bear whilst living in the college.[20]

A second legend is that it is possible to walk from Cambridge to Oxford on land solely owned by Trinity. Several varieties of this legend exist – others refer to the combined land of Trinity College, Cambridge and Trinity College, Oxford, of Trinity College, Cambridge and Christ Church, Oxford, or St John's College, Oxford and St John's College, Cambridge. All are almost certainly false.

Trinity is often cited as the inventor of an English, less sweet, version of crème brûlée, known as "Trinity burnt cream",[21][22] or "crème brûlée Trinity". The burnt-cream, first introduced at Trinity High Table in 1879, in fact differs quite markedly from French recipes, the earliest of which is from 1691.

Trinity in Camberwell

Trinity College has a long-standing relationship with the Parish of St George's, Camberwell,[23] in South London. Students from the College have helped to run holiday schemes for children from the parish since 1966. The relationship was formalised in 1979 with the establishment of Trinity in Camberwell as a registered charity (Charity Commission no. 279447)[24] which exists 'to provide, promote, assist and encourage the advancement of education and relief of need and other charitable objects for the benefit of the community in the Parish of St George's, Camberwell, and the neighbourhood thereof.'

Buildings and grounds

Great Gate

The Great Gate is the main entrance to the college, leading to the Great Court. A statue of the college founder, Henry VIII, stands in a niche above the doorway. In his right hand he holds a chair leg instead of the original sword and myths abound as to how the switch was carried out and by whom. In 1983 Trinity College undergraduate Lance Anisfeld, then vice President of CURLS (Cambridge Union Raving Loony Society) replaced the chair leg with a bicycle pump. Once discovered the following day, the college removed the pump and replaced with another chair leg. The original chair leg was auctioned off by TV Presenter Chris Serle at a Cambridge Union Society charity raffle in 1985. In 1704, the University's first astronomical observatory was built on top of the gatehouse. Beneath the founder's statue are the coats of arms of Edward III, the founder of King's Hall, and those of his five sons who survived to maturity, as well as William of Hatfield, whose shield is blank as he died as an infant, before being granted arms.[25]

Great Court

Great Court (built principally 1599–1608) was the brainchild of Thomas Nevile, who demolished several existing buildings on this site, including almost the entirety of the former college of Michaelhouse. The sole remaining building of Michaelhouse was replaced by the then current Kitchens (designed by James Essex) in 1770–1775. The Master's Lodge is the official residence of the Sovereign when in Cambridge.[citation needed]

King's Hostel (built 1377–1416) is located to the north of Great Court, behind the Clock Tower This is, along with the King's Gate, the sole remaining building from King's Hall.

Bishop's Hostel (built 1671, Robert Minchin) is a detached building to the southwest of Great Court, and named after John Hacket, Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry. Additional buildings were built in 1878 by Arthur Blomfield.

Nevile's Court

Nevile's Court (built 1614) is located between Great Court and the river, this court was created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile, originally two-thirds of its current length and without the Wren Library. The court was extended and the appearance of the upper floor remodelled slightly in 1758 by James Essex. Cloisters run around the court, providing sheltered walkways from the rear of Great Hall to the college library and reading room as well as the Wren Library and New Court.

Wren Library (built 1676–1695, Christopher Wren) is located at the west end of Nevile's Court, the Wren is one of Cambridge's most famous and well-endowed libraries. Among its notable possessions are two of Shakespeare's First Folios, a 14th-century manuscript of The Vision of Piers Plowman, and letters written by Sir Isaac Newton. The Eadwine Psalter belongs to Trinity but is kept by Cambridge University Library. Below the building are the pleasant Wren Library Cloisters, where students may enjoy a fine view of the Great Hall in front of them, and the river and Backs directly behind.

New Court

New Court (or King's Court; built 1825, William Wilkins) is located to the south of Nevile's Court, and built in Tudor-Gothic style; this court is notable for the large tree in the centre. A myth is sometimes circulated that this was the tree from which the apple dropped onto Isaac Newton; in fact, Newton was at home in Woolsthorpe when he deduced his theory of gravity – and the tree is a sweet chestnut tree.[26] Many other "New Courts" in the colleges were built at this time to accommodate the new influx of students.

Other courts

Whewell's Court (actually two courts with a third in between, built 1860 & 1868, architect Anthony Salvin)[27] is located across the street from Great Court, and was entirely paid for by William Whewell, the Master of the college from 1841 until his death in 1866. The north range was later remodelled by W.D. Caroe.

Angel Court (built 1957–1959, H. C. Husband) is located between Great Court and Trinity Street, and is used along with the Wolfson Building for accommodating first year students.

The Wolfson Building (built 1968–1972, Architects Co-Partnership) is located to the south of Whewell's Court, on top of a podium above shops, this building resembles a brick-clad ziggurat, and is used exclusively for first-year accommodation. Having been renovated during the academic year 2005–06, rooms are now almost all en-suite.

Blue Boar Court (built 1989, MJP Architects and Wright) is located to the south of the Wolfson Building, on top of podium a floor up from ground level, and including the upper floors of several surrounding Georgian buildings on Trinity Street, Green Street and Sidney Street.

Burrell's Field (built 1995, MJP Architects)[28] is located on a site to the west of the main College buildings, opposite the Cambridge University Library.

There are also College rooms above shops in Bridge Street and Jesus Lane, behind Whewell's Court, and graduate accommodation in Portugal Street and other roads around Cambridge.

Chapel

Trinity College Chapel dates from the mid 16th Century and is Grade I listed.[29]

There are a number of memorials to former Fellows of Trinity within the Chapel, including statues, brasses, and two memorials to graduates and Fellows who died during the World Wars.[30] Among the most notable of these is a statue of Isaac Newton by Roubiliac, described by Sir Francis Chantrey as "the noblest, I think, of all our English statues."[31]

The Chapel is a performance space for the college choir which comprises around 30 Choral Scholars and 2 Organ Scholars, all of whom are ordinarily undergraduate members of the college.[32]

Grounds

The Fellows' Garden is located on the west side of Queen's Road, opposite the drive that leads to the Backs.

The Fellows' Bowling Green is located north of Great Court, between King's Hostel and the river. It is the site for many of the tutors' garden parties in the summer months, while the Master's Garden is located behind the Master's Lodge.

The Old Fields are located on the western side of Grange Road, next to Burrell's Field. It currently houses the college's gym, changing rooms, squash courts, badminton courts, rugby, hockey and football pitches along with tennis and netball courts.

Trinity Bridge

Trinity bridge is a stone built tripled-arched road bridge across the River Cam. It was built of Portland stone in 1765 to the designs of James Essex to replace an earlier bridge built in 1651 and is a Grade I listed building.[33]

Gallery

-

Great Gate

-

Clock Tower

-

Fellows' Bowling Green, with the oldest building in the college (originally part of King's Hall) in the background

-

Old Kitchen set up for a formal dinner

-

New Court after 2016 refurbishment

-

The River Cam as it flows past the back of Trinity, Trinity Bridge is visible and the punt house is to the right of the moored punts

-

The Avenue of lime and cherry trees, and wrought iron gate to Queen's Road viewed from the Backs

-

Sundial and shelter at the Fellows' Garden

-

1995 development of Burrell's Field

-

Blue Boar Court, with the Wolfson Building in the background.

Academic profile

Over the last 20 years, the college has always come at least eighth in the Tompkins Table, which ranks the 29 Cambridge colleges according to the academic performance of their undergraduates, and for the last six occasions it has been in first place. Its average position in the Tompkins Table over that period has been between second and third, higher than any other. In 2016, 45% of Trinity undergraduates achieved Firsts, 12 percentage points ahead of second place Pembroke – a recent record among Cambridge colleges.[34]

Admissions

Currently[when?], about 50% of Trinity's undergraduates attended independent schools. In 2006 it accepted a smaller proportion of students from state schools (39%) than any other Cambridge college, and on a rolling three-year average it has admitted a smaller proportion of state school pupils (42%) than any other college at either Cambridge or Oxford.[35][36][37] According to the Good Schools Guide, about 7% of British school-age students attend private schools, although this figure refers to students in all school years – a higher proportion attend private schools in their final two years before university. Trinity states that it disregards what type of school its applicants attend, and accepts students solely on the basis of their academic prospects.

Trinity admitted its first woman graduate student in 1976 and its first woman undergraduate in 1978. It elected its first female fellow (Marian Hobson) in 1977.[38]

Scholarships and prizes

The Scholars, together with the Master and Fellows, make up the Foundation of the College.

In order of seniority:

Research Scholars receive funding for graduate studies. Typically one must graduate in the top ten percent of one's class and continue for graduate study at Trinity. They are given first preference in the assignment of college rooms and number approximately 25.

The Senior Scholars usually consist of those who attain a degree with First Class honours or higher in any year after the first of an undergraduate tripos. The college pays them a stipend of £250 a year and allows them to choose rooms directly following the research scholars. There are around 40 senior scholars at any one time.

The Junior Scholars usually consist of those who attained a First in their first year. Their stipend is £175 a year. They are given preference in the room ballot over 2nd years who are not scholars.

These scholarships are tenable for the academic year following that in which the result was achieved. If a scholarship is awarded but the student does not continue at Trinity then only a quarter of the stipend is given. However all students who achieve a First are awarded an additional £240 prize upon announcement of the results.

Many final year undergraduates who achieve first-class honours in their final exams are offered full financial support, through a scheme known as Internal Graduate Studentships, to read for a Master's degree at Cambridge[39] (this funding is also sometimes available for students who achieved high second-class honours marks). Other support is available for PhD degrees. The College also offers a number of other bursaries and studentships open to external applicants. The right to walk on the grass in the college courts is exclusive to Fellows of the college and their guests. Scholars do, however, have the right to walk on the Scholars' Lawn, but only in full academic dress.[citation needed]

Traditions

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

Great Court Run

The Great Court Run is an attempt to run round the 400-yard perimeter of Great Court (approximately 367m), in the 43 seconds of the clock striking twelve. Students traditionally attempt to complete the circuit on the day of the Matriculation Dinner. It is a rather difficult challenge: one needs to be a fine sprinter to achieve it, but it is by no means necessary to be of Olympic standard, despite assertions made in the press.[40]

It is widely believed that Sebastian Coe successfully completed the run when he beat Steve Cram in a charity race in October 1988. Coe's time on 29 October 1988 was reported by Norris McWhirter to have been 45.52 seconds, but it was actually 46.0 seconds (confirmed by the video tape), while Cram's was 46.3 seconds. The clock on that day took 44.4 seconds (i.e., a "long" time, probably two days after the last winding) and the video film confirms that Coe was some 12 metres short of his finish line when the fateful final stroke occurred. The television commentators were disingenuous in suggesting that the dying sounds of the bell could be included in the striking time, thereby allowing Coe's run to be claimed as successful.[citation needed]

One reason Olympic runners Cram and Coe found the challenge so tough is that they started at the middle of one side of the court, thereby having to negotiate four right-angle turns. In the days when students started at a corner, only three turns were needed. In addition, Cram and Coe ran entirely on the flagstones, while until 2017 students have typically cut corners to run on the cobbles.[citation needed]

The Great Court Run was portrayed in the film Chariots of Fire about the British Olympic runners of 1924.

Until the mid-1990s, the run was traditionally attempted by first-year students at midnight following their matriculation dinner.[41] Following a number of accidents to undergraduates running on slippery cobbles,[citation needed] the college now organises a more formal Great Court Run, at 12 noon on the day of the matriculation dinner: while some contestants compete seriously, many others run in fancy dress and there are prizes for the fastest man and woman in each category.[42]

Open-air concerts

One Sunday each June (the exact date depending on the university term), the College Choir perform a short concert immediately after the clock strikes noon. Known as Singing from the Towers, half of the choir sings from the top of the Great Gate, while the other half sings from the top of the Clock Tower approximately 60 metres away, giving a strong antiphonal effect. Midway through the concert, the Cambridge University Brass Ensemble performs from the top of the Queen's Tower.[43]

Later that same day, the College Choir gives a second open-air concert, known as Singing on the River, where they perform madrigals and arrangements of popular songs from a raft of punts lit with lanterns or fairy lights on the river. For the finale, John Wilbye's madrigal Draw on, sweet night, the raft is unmoored and punted downstream to give a fade out effect. As a tradition, however, this latter concert dates back only to the mid-1980s, when the College Choir first acquired female members. In the years immediately before this, an annual concert on the river was given by the University Madrigal Society.[44]

Mallard

Another tradition relates to an artificial duck known as the Mallard, which should reside in the rafters of the Great Hall. Students occasionally moved the duck from one rafter to another without permission from the college. This is considered difficult; access to the Hall outside meal-times is prohibited and the rafters are dangerously high, so it was not attempted for several years. During the Easter term of 2006, the Mallard was knocked off its rafter by one of the pigeons which enter the Hall through the pinnacle windows. It was reinstated by students in 2016, and is only visible from the far end of the hall.[45][46]

Chair legs and bicycles

The sceptre held by the statue of Henry VIII mounted above the medieval Great Gate was replaced with a chair leg as a prank many years ago. It has remained there to this day: when in the 1980s students exchanged the chair leg for a bicycle pump, the College replaced the chair leg.

For many years it was the custom for students to place a bicycle high in branches of the tree in the centre of New Court. Usually invisible except in winter, when the leaves had fallen, such bicycles tended to remain for several years before being removed by the authorities. The students then inserted another bicycle. [citation needed]

College rivalry

The college remains a great rival of St John's which is its main competitor in sports and academia (John's is situated next to Trinity). This has given rise to a number of anecdotes and myths. It is often cited as the reason why the older courts of Trinity generally have no J staircases, despite including other letters in alphabetical order. A far more likely reason remains the absence of the letter J in the Latin alphabet, and that St John's College's older courts also lack J staircases. There are also two small muzzle-loading cannons on the bowling green pointing in the direction of John's, though this orientation may be coincidental. Another story sometimes told is that the reason that the clock in Trinity Great Court strikes each hour twice is that the fellows of St John's once complained about the noise it made.[citation needed]

Minor traditions

Trinity College undergraduate gowns are readily distinguished from the black gowns favoured by most other Cambridge colleges. They are instead dark blue with black facings. They are expected to be worn to formal events such as formal halls and also when an undergraduate sees the Dean of the College in a formal capacity.

Trinity students, along with those of King's and St John's, are the first to be presented to the Congregation of the Regent House at graduation.

College Grace

Each evening before dinner, grace is recited by the senior fellow presiding, as follows:

Benedic, Domine, nos et dona tua, |

Bless us, Lord, and these gifts |

If both of the two high tables are in use then the following antiphonal formula is prefixed to the main grace:

A. Oculi omnium in te sperant Domine: |

The eyes of all are on you, Lord: |

Following the meal, the simple formula Benedicto benedicatur is pronounced.[48]

People associated with the college

Notable fellows and alumni

The Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge contains the graves of 27 Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge most of whom are also commemorated in Trinity College Chapel with brass plaques. One of the most famous recent additions to Trinity's alumni is Prince Charles, heir to the British Throne.

Marian Hobson was the first woman to become a Fellow of the college, having been elected in 1977,[49][50] and her portrait now hangs in the college hall along with those of other notable members of the college.[51] Other notable female Fellows include Anne Barton, Marilyn Strathern, Catherine Barnard, Lynn Gladden and Rebecca Fitzgerald.

Nobel Prize winners

| Name | Field | Year |

|---|---|---|

| John Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh | Physics | 1904 |

| Joseph John (J. J.) Thomson | Physics | 1906 |

| Ernest Rutherford | Chemistry | 1908 |

| William Bragg | Physics | 1915 |

| Lawrence Bragg | Physics | 1915 |

| Charles Glover Barkla | Physics | 1917 |

| Niels Bohr | Physics | 1922 |

| Francis William Aston | Chemistry | 1922 |

| Archibald V. Hill | Physiology or Medicine | 1922 |

| Austen Chamberlain | Peace | 1925 |

| Owen Willans Richardson | Physics | 1928 |

| Frederick Hopkins | Physiology or Medicine | 1929 |

| Edgar Douglas Adrian | Physiology or Medicine | 1932 |

| Henry Dale | Physiology or Medicine | 1936 |

| George Paget Thomson | Physics | 1937 |

| Bertrand Russell | Literature | 1950 |

| Ernest Walton | Physics | 1951 |

| Richard Synge | Chemistry | 1952 |

| John Kendrew | Chemistry | 1962 |

| Alan Hodgkin | Physiology or Medicine | 1963 |

| Andrew Huxley | Physiology or Medicine | 1963 |

| Brian David Josephson | Physics | 1973 |

| Martin Ryle | Physics | 1974 |

| James Meade | Economic Sciences | 1977 |

| Pyotr Kapitsa | Physics | 1978 |

| Walter Gilbert | Chemistry | 1980 |

| Aaron Klug | Chemistry | 1982 |

| Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar | Physics | 1983 |

| James Mirrlees | Economic Sciences | 1996 |

| John Pople | Chemistry | 1998 |

| Amartya Sen | Economic Sciences | 1998 |

| Venkatraman Ramakrishnan | Chemistry | 2009 |

| Sir Gregory Paul Winter | Chemistry | 2018 |

| Didier Queloz | Physics | 2019 |

Fields Medallists

Trinity College also has claim to a number of winners of the Fields Medal (commonly regarded as the mathematical equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

| Name | Year |

|---|---|

| Michael Atiyah | 1966 |

| Alan Baker | 1970 |

| Richard Borcherds | 1998 |

| Timothy Gowers | 1998 |

Turing Award winners

| Name | Year |

|---|---|

| James H. Wilkinson | 1970 |

British Prime Ministers

| Name | Party | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Spencer Perceval | Tory | 1809–1812 |

| Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey | Whig | 1830–1834 |

| William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne | Whig | 1834–1841 |

| Arthur Balfour | Conservative | 1902–1905 |

| Henry Campbell-Bannerman | Liberal | 1905–1908 |

| Stanley Baldwin | Conservative | 1923–1924 1924–1929 1935–1937 |

Other Trinity politicians include Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, courtier of Elizabeth I; William Waddington, Prime Minister of France; Erskine Hamilton Childers, fourth President of Ireland; Jawaharlal Nehru, the first and longest serving Prime Minister of India; Rajiv Gandhi, Prime Minister of India; Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore; Samir Rifai, Prime Minister of Jordan; Richard Blumenthal, incumbent senior US Senator from Connecticut, William Whitelaw, Margaret Thatcher's Home Secretary and subsequently Deputy Prime Minister; and Rahul Gandhi, President of the Indian National Congress.

Masters

The head of Trinity College is called the Master.

The role is a Crown appointment, formerly made by the Monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister.[52] Nowadays the Fellows of the College propose a new Master for the appointment,[53] but the final decision is still in principle that of the Monarch. The first Master, John Redman, was appointed in 1546. Six Masters subsequent to Rab Butler had been Fellows of the College prior to becoming Master (Honorary Fellow in the case of Martin Rees), the last of these being Sir Gregory Winter, appointed on 2 October 2012.[54][55] He was succeeded by Dame Sally Davies, the first female Master of Trinity College, on 8 October 2019.[56]

See also

- Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, partially funded by Trinity

Notes

- ^ James, Simon (4 August 2008). Latin Matters: A Little Knowledge Is A Dangerous Thing. Pavilion Books. ISBN 9781906032319 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Annual Report of the Trustees and Financial Statements for the year ended 30 June 2019" (PDF). Trinity College, Cambridge. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Kirk, Ashley; Peck, Sally (1 October 2019). "Why Trinity is the best Cambridge college, according to our Oxbridge league table". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Stephen Brewer, Donald Olson (2006). Best Day Trips from London: 25 Great Escapes by Train, Bus Or Car. Frommer's. p. 56. ISBN 0-470-04453-5.

- ^ "Exclusive: Christ's triumphant in 2019 Tompkins Table".

- ^ "Research at Cambridge/Nobel Prize". University of Cambridge. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "Famous Trinity College Medallists and Prize Winners". Trin.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Murray, Bill; Murray, William J (1 January 1998). The World's Game: A History of Soccer. ISBN 9780252067181.

- ^ "Westminster School Intranet". Intranet.westminster.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ a b "The colleges and halls – Trinity College | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Sample, Ian (6 April 2011). "Martin Rees wins controversial £1m prize". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Oxford and Cambridge university colleges hold £21bn in riches". 28 May 2018.

- ^ Ruddick, Graham (28 January 2012). "Cambridge's Trinity College buys 50pc stake in Tesco stores". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Cambridge Science Park". UK Science Parks Association. November 2006. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Trinity College buys O2 concert arena". Daily Telegraph. 9 October 2009. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Big Oil and deep sea drilling: The corporations underpinning Cambridge colleges' investments". Varsity Online. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ "Cambridge's Trinity College lawn dug up by Extinction Rebellion". BBC News. 17 February 2020.

- ^ "Trinity College and USS – Trinity College Cambridge". Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ "An open letter to the Council and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge". Google Docs. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ "University". International Byron Society. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Cambridge Trinity Burnt Cream". thefoody.com. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010.

- ^ "TRINITY BURNT CREAM". Trinity College, Cambridge. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "Diocese of Southwark:Parishes". Diocese of Southwark. Archived from the original on 4 September 2004.

- ^ "Charity Commission Homepage". Charity-commission.gov.uk. 21 May 2007. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Trinity Tour". Trin.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Trinity College Cambridge, "The Fountain", Issue 14, Spring 2012, p.12

- ^ "Whewell's Court, Trinity College". British Listed Buildings. English Heritage. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ "MJP Architects". MJP Architects. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Trinity College, the Buildings Surrounding Great Court, Nevile's Court and New Court, and Including – Cambridge – Cambridgeshire – England. British Listed Buildings. Retrieved on 24 August 2013.

- ^ Index of memorials in Trinity College Chapel and Ante-Chapel. Trinity College Chapel. Retrieved on 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Trinity College Chapel - Isaac Newton". trinitycollegechapel.com. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Trinity College Choir - About". www.trinitycollegechoir.com.

- ^ Historic England. "TRINITY COLLEGE, TRINITY BRIDGE (1331804)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ "The Tompkins Table 2016: Christ's has risen".

- ^ "Cambridge 2005/2006 admissions statistics by college" (PDF). Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Cambridge 2004/2005 admissions statistics by college" (PDF). Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Oxford 3-year average admissions statistics by college". Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Trinity College, Cambridge. "Trinity College Cambridge – 20th Century to Present". Trin.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Trinity Graduate Student Funding Awards – Trinity College Cambridge". Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Student breaks 'Chariots of Fire' record Times Online article. 27 October 2007.

- ^ "Runners' latest attempt to beat the college clock", ITV News, 13 October 2015

- ^ "Great Court run reverts to tradition", Trinity College, 11 October 2017

- ^ "Trinity College Choir – Concerts". trinitycollegechoir.com.

- ^ "Search". Concert Programmes.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Geoffrey Winthrop Young, John Hurst, Richard Williams, The Roof-Climber's Guide to Trinity: Omnibus Edition p.29, Oleander Press, 2013, ISBN 0900891920

- ^ Jovan Powar, Kate Pfeffer, Travisty Issue 1

- ^ Psalm 145:15–16

- ^ Reginald H. Adams, The College Graces of Oxford and Cambridge (Oxford: Perpetua Press, 1992).

- ^ "Marian Hobson". Trinity College Library. 3 October 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ "People - Marian Hobson, CBE FBA MA PhD (Cantab)". Department of French. Queen Mary, University of London. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ "THE 'HIDDEN HISTORIES' OF WOMEN AT TRINITY" (PDF). Trinity College Cambridge. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "Trinity College Cambridge – Master of Trinity – Lord Rees (of Ludlow)". Trin.cam.ac.uk. 15 January 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ McKitterick, David. "Welcoming speech at the Master's Installation Dinner". Annual Record 2013. Trinity College, Cambridge. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Sir Gregory Winter CBE FRS appointed Master of Trinity College, Cambridge University". Number10.gov.uk. 16 December 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Trinity College, Cambridge. Master of Trinity". Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ "Professor Dame Sally Davies appointed Master of Trinity". 8 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.