Rani dialect: Difference between revisions

Added {{Technical}} tag |

Sample text Tags: Reverted Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

The '''Rani dialect'''{{sfn|Milewski|1930|p=297, 301}} or '''Lechito-Rani [[supradialect]]'''{{sfn|Batowski|1927|p=259}} is an [[Extinct language|extinct]] [[Slavic languages|Slavic]] [[Lechitic languages|Lechitic dialect]] used by the [[Rani (tribe)|Rani tribe]]{{sfn|Milewski|1930|p=306}} – the [[Middle Ages|medieval]] [[Slavs|Slavic]] inhabitants of the island of [[Rügen]] (in Rani dialect: ''Rȯjana'', ''Rāna''{{sfn|Milewski|1930|p=306}}) and its opposite coast.{{sfn|Łęgowski|Lehr-Spławiński|1922|p=114}} This dialect, because of its closer affinity to the [[Polabian language|Drevani language]] than to the [[Pomeranian language|Pomeranian area]], should be classified as a [[West Lechitic dialects|West Lechitic dialect]].{{sfn|Łęgowski|Lehr-Spławiński|1922|p=136}} |

The '''Rani dialect'''{{sfn|Milewski|1930|p=297, 301}} or '''Lechito-Rani [[supradialect]]'''{{sfn|Batowski|1927|p=259}} is an [[Extinct language|extinct]] [[Slavic languages|Slavic]] [[Lechitic languages|Lechitic dialect]] used by the [[Rani (tribe)|Rani tribe]]{{sfn|Milewski|1930|p=306}} – the [[Middle Ages|medieval]] [[Slavs|Slavic]] inhabitants of the island of [[Rügen]] (in Rani dialect: ''Rȯjana'', ''Rāna''{{sfn|Milewski|1930|p=306}}) and its opposite coast.{{sfn|Łęgowski|Lehr-Spławiński|1922|p=114}} This dialect, because of its closer affinity to the [[Polabian language|Drevani language]] than to the [[Pomeranian language|Pomeranian area]], should be classified as a [[West Lechitic dialects|West Lechitic dialect]].{{sfn|Łęgowski|Lehr-Spławiński|1922|p=136}} |

||

The dialects of Rügen have left |

The dialects of Rügen have left little monuments, so the main source of knowledge about them is the [[Toponymy|toponyms]] and personal names of Slavic origin recorded in medieval chronicles. |

||

== Features == |

== Features == |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

Written monuments lack the distinction of the series ''s'', ''c'', ''z'' from ''š'', ''č'', ''ž'', which most likely indicates the [[mazuration]] of the Rugian dialect.{{sfn|Łęgowski|Lehr-Spławiński|1922|p=134}} |

Written monuments lack the distinction of the series ''s'', ''c'', ''z'' from ''š'', ''č'', ''ž'', which most likely indicates the [[mazuration]] of the Rugian dialect.{{sfn|Łęgowski|Lehr-Spławiński|1922|p=134}} |

||

== Sample Text == |

|||

Rani Text: |

|||

"Wojwodë Wislaw z Rujani i wojwodka Margareta, jego velikë lubowë, odbëwaji na pąt. Oni jidi do lodi prëz slizëkë môstekë. Knedz drusët nosim wojwodskim ljudem pri tëm. Woda v mori jest zimënë, gląbëkë i slonë. Ljudi nošji tepëlë plaštë, bo pogoda jest zimënë. Erik Menved, krôl Danow i Slovanow, jest takže medzë na lodu. On nosët zlotą koronę. Dva panošë z polka, Satko za Zatela i slovanski Viriš, dmuchači veselë na dolgich fanfarach.” |

|||

German Translation: |

|||

"Fürst Wizlaw von Rügen und Fürstin Margarete, seine große Liebe, machen eine Reise. Sie gehen über einen rutschigen Steg zum Schiff. Ein Geistlicher hilft unserem fürstlichen Paar dabei. Das Wasser des Meeres ist kalt, tief und salzig. Die Menschen tragen warme Mäntel, da das Wetter kalt ist. Auch Erik Menved, der König der Dänen und Slawen, ist mitten auf dem Schiff. Er trägt eine goldene Krone. Zwei Knappen aus der Heerschar, Satko zu Saatel und der wendische Vyriz, blasen fröhlich auf langen Fanfaren.”<ref>{{Cite web |date=October 12th, 2023 |title=wizlaw.de |url=https://wizlaw.de/html/polabisch.html |website=wizlaw.de}}</ref> |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 01:56, 13 October 2023

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (June 2023) |

| Rani | |

|---|---|

| Lechito-Rani | |

| Native to | Germany |

| Region | Rügen |

| Extinct | 1404[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

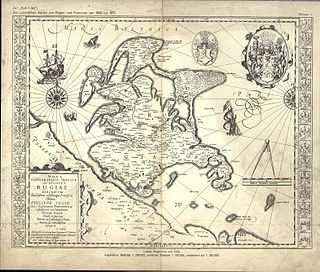

Map of Rügen from 1608 by Eilhardus Lubinus | |

The Rani dialect[3] or Lechito-Rani supradialect[4] is an extinct Slavic Lechitic dialect used by the Rani tribe[5] – the medieval Slavic inhabitants of the island of Rügen (in Rani dialect: Rȯjana, Rāna[5]) and its opposite coast.[6] This dialect, because of its closer affinity to the Drevani language than to the Pomeranian area, should be classified as a West Lechitic dialect.[7]

The dialects of Rügen have left little monuments, so the main source of knowledge about them is the toponyms and personal names of Slavic origin recorded in medieval chronicles.

Features

Development of vowels and sonants

The development of Proto-Slavic nasals coincided with that in other Lechitic dialects - the PS *ǫ gave a regular ą̊, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Dǫsno, *Gǫslicě, *Dǫbrovy, *Ǫglinъ, whereas in the case of PS *ę Lechitic apophony happened and before the hard dental consonants it gave 'ą̊, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Boręta, *Svętъ Ostrovъ, *Svętъ Gordъ, while in the other positions narrow ę̇, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Borętinъ, *Gněvętinъ, *Vęťemirъ.[8][9]

Lechitic apophony also shows the development of *ě – before the hard dental consonants it gave *a, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Lěsъkovica, *Pěsъkъ, *Strělovo, while in other positions e, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Gněvętinъ, *Pasěka, *Těšimirъ.[10][11]

Proto-Slavic *e before originally palatalized consonants narrows to ė, transcribed alternately by ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨y⟩, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Bezdědьje, *Kamenišče, *Melьnica, while in other positions it gives an e, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Berza, *Grebenovъ, *Jezero.[12][13] The narrowing of *e to ė or i before originally palatal consonants ties the Rani dialect to the Drevani area.[12] No Lechitic apophony *e > ’o.

The Proto-Slavic *o probably developed into the narrow ȯ, denoted in writing ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ or ⟨uo⟩, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Borislavъ, *Dobroslavъ, *Olьšanica.[14] In addition, *o underwent reduction to a reduced vowel of the type ə under certain hard-to-define conditions, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Dobromyslъ, *Ľuboradъ.[12] Especially often this reduction occurs in the auslaut, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Bukovo, *Bělikovo, *Jarъkovo,[15] although there are also forms without this reduction, such as. Template:Lang-la < PS *Slavъko.[16] The anlaut *o- tends to take on a prosthetic v- (*o- > u̯o- > vo-), e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Ostrožьn-, *Obľuže, *Svętъ Ostrovъ,[17] which connects the Rani dialect to all of Polabie, Pomerania, Lusatia, Greater Poland and Bohemia.

Proto-Slavic *a as a rule gave a, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Babinъ, *Kamenьcь, *Grabovo.[16][17] However, it developed differently in the *ra- group, where it gave re-, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Radoměrъ, *Radimь[16] next to the rarer ra- such as Template:Lang-la < PS *Radoslavъ[18] and perhaps in the *ja- group, where the records are ambiguous, since, for example, next to Template:Lang-la there is Template:Lang-la < PS *Jarogněvъ.[16] In addition, in the auslaut *a was reduced, e.g.. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *gora, *lopata, *plaxъta.[18]

The Proto-Slavic *u gives a constant u, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Bukovo, *Ľubinъ, *Sulislavъ,[19][18] except for the position before the nasal consonants m and n, where it seems to give o, e.g. Template:Lang-la (next to Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la), Template:Lang-la < PS *Perunъ, *Strumenьky.[20]

The Proto-Slavic *i generally gave i, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Babinъ, *Bǫdinъ, *Gordišče.[19][18] In the position before *r, however, it must have been raised to e or a, as evidenced by notations like Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Jaromirъ, *Myslimirъ, *Sirakovo.[18]

The Proto-Slavic *y essentially gave y, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Bydъgoščь, *Bykovo, *Pribyslavъ, with a strong tendency to diphthongize to oi in the position after labial consonants, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Myslikovъ, *Myslimirъ, Vyslavъ.[19][21] In addition, *y was reduced to ə in some positions, such as. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Dǫbrovy, *Lěpylovy.[19]

Yers in weak position disappeared,[19][22] while in the strong position *ь gave e, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Kamenьcь, *Korьcь, *Kozьlъ, and *ъ most likely gave o, for which there is only one example: Template:Lang-la < PS *Cŕ̥kъvь.[22]

Proto-Slavic group *TorT switches to TarT almost without exceptions, np. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Bornimъ, *Xorna, *Gordьcь.[19][23] The *TolT group usually switches to TloT, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Golvy, *Golvьnica, *Solnicě, although there are examples for TolT, e.g. Template:Lang-la < PS *Soldъkoviťě.[24] The *TerT group generally gives TreT, sometimes written ⟨TriT⟩ np. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Bergy, *Berzьnica, *Beržanъky, exceptional TerT is only the Template:Lang-la < PS *Žerbętinъ.[24] No examples for *TelT.[24]

The Proto-Slavic *r̥ (*ъr) constantly gives ar, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Kr̥ninъ, *Gr̥nьčьky.[24] In the case of *ŕ̥ (*ьr) there was a Lechitic apophony to ar before the hard dental consonants, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Bŕ̥dъko, *Čŕ̥na Glova, while in the other positions *ŕ̥ gives er (also noted as ⟨ir⟩), e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Čŕ̥vicě, *Cŕ̥kъvь, *Cŕ̥kъvišče.[25][26] Proto-Slavic *l̥ and *ĺ̥ (*ъl and *ьl) merged to give ol, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Dl̥gъ Mostъ, *Pustivĺ̥kъ, *Stl̥pьskъ.[25][27]

Development of consonants

Primary palatal consonants have dyspalatalized, except when followed by back vowels. This palatalization is noted in records such as Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Boręta, *Lěska, *Pěsъky, *Svinьja.[27] This links the Rani dialect with the Drevani dialect.[25][7]

Proto-Slavic *ť and *ď (< *t-j, *k-t; *d-j) gave c and ʒ, respectively, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Svěťenoviťь, *Blǫďaviťь, with the latter phoneme tending to transition into z, e.g. Template:Lang-la < PS *Meďerěčь.[28]

The Proto-Slavic group *šč has passed into st, e.g. Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-la < PS *Gordišče, *Ščapъlinъ.[29]

Written monuments lack the distinction of the series s, c, z from š, č, ž, which most likely indicates the mazuration of the Rugian dialect.[29]

Sample Text

Rani Text:

"Wojwodë Wislaw z Rujani i wojwodka Margareta, jego velikë lubowë, odbëwaji na pąt. Oni jidi do lodi prëz slizëkë môstekë. Knedz drusët nosim wojwodskim ljudem pri tëm. Woda v mori jest zimënë, gląbëkë i slonë. Ljudi nošji tepëlë plaštë, bo pogoda jest zimënë. Erik Menved, krôl Danow i Slovanow, jest takže medzë na lodu. On nosët zlotą koronę. Dva panošë z polka, Satko za Zatela i slovanski Viriš, dmuchači veselë na dolgich fanfarach.”

German Translation:

"Fürst Wizlaw von Rügen und Fürstin Margarete, seine große Liebe, machen eine Reise. Sie gehen über einen rutschigen Steg zum Schiff. Ein Geistlicher hilft unserem fürstlichen Paar dabei. Das Wasser des Meeres ist kalt, tief und salzig. Die Menschen tragen warme Mäntel, da das Wetter kalt ist. Auch Erik Menved, der König der Dänen und Slawen, ist mitten auf dem Schiff. Er trägt eine goldene Krone. Zwei Knappen aus der Heerschar, Satko zu Saatel und der wendische Vyriz, blasen fröhlich auf langen Fanfaren.”[30]

References

- ^ Werner Besch, Sprachgeschichte: Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und ihrer Erforschung2nd edition, Walter de Gruyter, 1998, p.2707, ISBN 3-11-015883-3 [1]

- ^ Lehr-Spławiński 1934, p. 23.

- ^ Milewski 1930, p. 297, 301.

- ^ Batowski 1927, p. 259.

- ^ a b Milewski 1930, p. 306.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 114.

- ^ a b Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 136.

- ^ Batowski 1927, p. 271.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 125-127.

- ^ Batowski 1927, p. 271-272.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Batowski 1927, p. 272.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 127-128.

- ^ Batowski 1927, p. 272-273.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Batowski 1927, p. 273.

- ^ a b Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d e f Batowski 1927, p. 274.

- ^ Milewski 1930, p. 295.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 130-131.

- ^ a b Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 131.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 131-132.

- ^ a b c d Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Batowski 1927, p. 275.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 132-133.

- ^ a b Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 133.

- ^ Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 133-134.

- ^ a b Łęgowski & Lehr-Spławiński 1922, p. 134.

- ^ "wizlaw.de". wizlaw.de. October 12th, 2023.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Bibliography

- Batowski, Henryk (1927). "Przyczynki do narzecza lechicko-rugijskiego". Slavia Occidentalis (in Polish). VI: 259–275.

- Łęgowski, Józef; Lehr-Spławiński, Tadeusz (1922). "Szczątki języka dawnych słowiańskich mieszkańców wyspy Rugji". Slavia Occidentalis (in Polish). II: 114–136.

- Lehr-Spławiński, Tadeusz (1934). O narzeczach Słowian nadbałtyckich (in Polish). Toruń.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Milewski, Tadeusz (1930). "Pierwotne nazwy wyspy Rugji i słowiańskich jej mieszkańców". Slavia Occidentalis (in Polish). IX: 292–306.