History of antisemitism: Difference between revisions

mention Timeline of antisemitism & Jewish history in the intro |

|||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

===Accusations of deicide=== |

===Accusations of deicide=== |

||

{{further|[[Deicide]]}} |

{{further|[[Deicide]]}} |

||

The first accusation that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus came in a sermon in 167 CE attributed to [[Melito of Sardis]] entitled ''Peri Pascha'', ''On the Passover''. This text blames the Jews for |

The first accusation that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus came in a sermon in 167 CE attributed to [[Melito of Sardis]] entitled ''Peri Pascha'', ''On the Passover''. This text blames the Jews for allowing King Herod and Caiaphas to execute Jesus, despite their calling as God's people. It say "you did not know, O Israel, that this one was the firstborn of God". The author does not attribute particular blame to [[Pontius Pilate]], but only mentions that Pilate washed his hands of guilt.<ref>[http://www.kerux.com/documents/KeruxV4N1A1.asp On the passover] pp. 57, 82, 92, 93</ref> The sermon is written in Greek, so does not use the Latin word for deicide, ''deicida''. At a time when Christians were widely persecuted, Melito's speech was an appeal to Rome to spare Christians.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

According to a Latin dictionary, the the Latin word ''deicidas'' was used by the fourth century, by Peter Chrystologus in his sermon number 172.<ref>Charleton Lewis and Charles Short, ''Latin Dictionary'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/resolveform?lang=Latin Latin Dictionary]</ref> |

According to a Latin dictionary, the the Latin word ''deicidas'' was used by the fourth century, by Peter Chrystologus in his sermon number 172.<ref>Charleton Lewis and Charles Short, ''Latin Dictionary'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/resolveform?lang=Latin Latin Dictionary]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 10:13, 3 April 2007

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2007) |

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of antisemitism, hostile actions or discrimination against Jews as a religious or ethnic group goes back many centuries. This article notes significant events in the history of antisemitism, which has been called "the longest hatred."[1] It includes important antisemitic actions, events in the history of antisemitic thought, actions taken to combat or relieve the effects of antisemitism, and events that affected the prevalence of antisemitism in later years. Timeline of antisemitism lists year-by-year chronology of antisemitic events. The article Jewish history gives a wider perspective of the Jewish history.

Ancient times

Early animosity towards Jews

The earliest occurrence of antisemitism has been the subject of debate among scholars. Different writers use different definitions of antisemitism. Some use the term "religious antisemitism" to refer to animosity towards Judaism as a religion rather than to Jews defined as an ethnic or racial group. The term "anti-Judaism" is also used in a similar sense.

Professor Peter Schafer of the Freie University of Berlin has argued that antisemitism was first spread by "the Greek retelling of ancient Egyptian prejudices". In view of the anti-Jewish writings of the Egyptian priest Manetho, Schafer suggests that antisemitism may have emerged "in Egypt alone".[2] The hostility commonly faced by Jews in the Diaspora has been extensively described by John M. G. Barclay of the University of Durham.[3] The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria described an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in Flaccus, in which thousands of Jews died. In the analysis of Pieter W. Van Der Horst, the cause of the violence in Alexandria was that Jews had been portrayed as misanthropes.[4] Gideon Bohak has argued that early animosity against Jews was not anti-Judaism unless it arose from attitudes held against Jews alone. Using this stricter definition, Bohak says that many Greeks had animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians.[5]

However, in terms of non-religious anti-semitism, the Roman Emperor Caligula and others, as well as the Roman public in general, were anti-semitic. For example, the Third Jewish War the Romans committed genocide against the Jews, plus the Jews were discriminated badly in the Roman occupation. Moreover, Jews were attacked mainly in the cities for issues relating to Jewish financial and intellectual success. This rather conflicts with the wide-spread Christian persecution origin for anti-semitism: therefore, it seems as though anti-semitism may have had an originate rooted in stereotyping and racial issues, not religious ones, though that is not to say religion had no part to play.

Expressions of attitudes to Jews in the New Testament

Although the majority of the New Testament was written by Jews who became followers of Jesus, there are a number of passages in the New Testament that some see as antisemitic, or have been used for antisemitic purposes, most notably:

- Jesus speaking to a group of Pharisees: "I know that you are descendants of Abraham; yet you seek to kill me, because my word finds no place in you. I speak of what I have seen with my Father, and you do what you have heard from your father. They answered him, "Abraham is our father." Jesus said to them, "If you were Abraham's children, you would do what Abraham did. ... You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father's desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do with the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks according to his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies. But, because I tell the truth, you do not believe me. Which of you convicts me of sin? If I tell the truth, why do you not believe me? He who is of God hears the words of God; the reason why you do not hear them is you are not of God." (John 8:37-39, 44-47, RSV)

- Stephen speaking before a synagogue council just before his execution: "You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy Spirit. As your fathers did, so do you. Which of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? And they killed those who announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now betrayed and murdered, you who received the law as delivered by angels and did not keep it." (Acts 7:51-53, RSV)

- "Behold, I will make those of the synagogue of Satan who say that they are Jews and are not, but lie — behold, I will make them come and bow down before your feet, and learn that I have loved you." (Revelation 3:9, RSV).

Some biblical scholars point out that Jesus and Stephen are presented as Jews speaking to other Jews, and that their use of broad accusation against Israel is borrowed from Moses and the later Jewish prophets (e.g. Deut 9:13-14; 31:27-29; 32:5, 20-21; 2 Kings 17:13-14; Is 1:4; Hos 1:9; 10:9). Jesus once calls his own disciple Peter 'Satan' (Mk 8:33). Other scholars hold that verses like these reflect the Jewish-Christian tensions that were emerging in the late first or early second century, and do not originate with Jesus. Today, nearly all Christian denominations de-emphasize verses such as these, and reject their use and misuse by antisemites.

Drawing from the Jewish prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 31:31-34), the New Testament taught that with the death of Jesus a new covenant was established which rendered obsolete and in many respects superseded the first covenant established by Moses (Hebrews 8:7-13; Lk 22:20). Observance of the earlier covenant traditionally characterizes Judaism. This New Testament teaching, and later variations to it, are part of what is called supersessionism. However, the early Jewish followers of Jesus continued to practice circumcision and observe dietary laws, which is why the failure to observe these laws by the first Gentile Christians became a matter of controversy and dispute some years after Jesus' death (Acts 11:3; 15:1ff; 16:3).

The New Testament holds that Jesus' (Jewish) disciple Judas Iscariot (Mark14:43-46), the Roman governor Pontius Pilate along with Roman forces (John 19:11; Acts 4:27) and Jewish leaders and people of Jerusalem were (to varying degrees) responsible for the death of Jesus (Acts 13:27); Diaspora Jews are not blamed for events which were clearly outside their control.

After Jesus' death, the New Testament portrays the Jewish religious authorities in Jerusalem as hostile to Jesus' followers, and as occasionally using force against them. Stephen is executed by stoning (Acts 7:58). Before his conversion, Saul puts followers of Jesus in prison (Acts 8:3; Galatians 1:13-14; 1 Timothy 1:13). After his conversion, Saul is whipped at various times by Jewish authorities (2 Corinthians 11:24), and is accused by Jewish authorities before Roman courts (e.g., Acts 25:6-7). However, opposition from Gentiles is also cited repeatedly (2 Corinthians 11:26; Acts 16:19ff; 19:23ff). More generally, there are widespread references in the New Testament to suffering experienced by Jesus' followers at the hands of others (Romans 8:35; 1 Corinthians 4:11ff; Galatians 3:4; 2 Thessalonians 1:5; Hebrews 10:32; 1 Peter 4:16; Revelation 20:4).

Accusations of deicide

The first accusation that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus came in a sermon in 167 CE attributed to Melito of Sardis entitled Peri Pascha, On the Passover. This text blames the Jews for allowing King Herod and Caiaphas to execute Jesus, despite their calling as God's people. It say "you did not know, O Israel, that this one was the firstborn of God". The author does not attribute particular blame to Pontius Pilate, but only mentions that Pilate washed his hands of guilt.[6] The sermon is written in Greek, so does not use the Latin word for deicide, deicida. At a time when Christians were widely persecuted, Melito's speech was an appeal to Rome to spare Christians.[citation needed]

According to a Latin dictionary, the the Latin word deicidas was used by the fourth century, by Peter Chrystologus in his sermon number 172.[7]

Persecution of Jews in the Middle Ages

There was continuity in the hostile attitude to Judaism from the ancient Roman Empire into the medieval period. From the 9th century CE the Islamic world imposed dhimmi laws on both Christian and Jewish minorities. In the later Middle Ages in Europe there was full-scale persecution in many places, with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions and massacres. A main justification of prejudice against Jews in Europe was religious.

Continuation of accusations of deicide

Though not part of Roman Catholic dogma, many Christians, including members of the clergy, held the Jewish people collectively responsible for killing Jesus. According to this interpretation, both the Jews present at Jesus’ death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time had committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing.[8]

Restriction to marginal occupations

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to the Jews, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, tolerated then as a "necessary evil". Catholic doctrine of the time held that lending money for interest was a sin, and forbidden to Christians. Not being subject to this restriction, Jews dominated this business. The Torah and later sections of the Hebrew Bible criticise Usury but interpretations of the Biblical prohibition vary. Since few other occupations were open to them, Jews were motivated to take up money lending. This was said to show Jews were insolent, greedy, usurers, and subsequently lead to many negative stereotypes and propaganda. Natural tensions between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) were added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants who were forced to pay their taxes to Jews could personify them as the people taking their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords on whose behalf the Jews worked.

Disabilities and restrictions

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations varying with place and time, and determined by the influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden. The number of Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos, and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own, were forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and suffered a variety of other measures, including restrictions on dress.

Clothing

Main article: yellow badge, Judenhut

The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was the first to proclaim the requirement for Jews to wear something that distinguished them as Jews. It could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape of a star or circle or square, a hat (Judenhut), or a robe. In many localities, members of the medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as guild members) were prestigious, while others ostracised outcasts such as lepers, reformed heretics and prostitutes. Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid whenever the king needed to raise funds.

The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns sanctioned by the papacy that took place from the end of the 11th century until the 13th century. They began as endeavors to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims but developed into territorial wars.

The mobs accompanying the first three Crusades, and particularly the People's Crusade accompanying the first Crusade, attacked the Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and put many Jews to death. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Mayence, and Cologne, were slain by a mob army. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhineland cities alone between May and July, 1096. Before the Crusades the Jews had practically a monopoly of trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of merchant traders among the Christians, and from this time onward restrictions on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent.[citation needed] The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against the Jews as against the Muslims, though attempts were made by bishops during the first Crusade and the papacy during the second Crusade to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III, and formed the turning point in the medieval history of the Jews.

In the County of Toulouse (now part of southern France) the Jews were received on good terms until the Albigensian Crusade. Toleration and favour shown to the Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church against the Counts of Toulouse. Following the Crusaders' successful wars against Raymond VI and Raymond VII, the counts were required to discriminate against Jews like other Christian rulers. In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII, underwent a similar ceremony where he was obliged to prohibit the public employment of Jews, this time at Notre Dame in Paris. Explicit provisions on the subject were included in the Treaty of Meaux (1229). By the next generation a new, zealously Catholic, ruler was arresting and imprisoning Jews for no crime, raiding their houses, seizing their cash, and removing their religious books. They were then released only if they paid a new "tax". A historian has argued that organised and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.[9][10]

The demonizing of the Jews

From around the 12th century through the 19th there were Christians who believed that some (or all) Jews possessed magical powers; some believed that they had gained these magical powers from making a deal with the devil. See also Judensau, Judeophobia.

Blood libels

Main articles: blood libel, list of blood libels against Jews

On many occasions, Jews were accused of a blood libel, the supposed drinking of blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. (Early Christians had been accused of a similar practice based on pagan misunderstanding of the Eucharist ritual.)[citation needed] According to the authors of these blood libels, the 'procedure' for the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses and then drunk. Finally, the child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed of, but in some instances rituals of black magic would be performed on it. This method, with some variations, can be found in all the alleged Christian descriptions of ritual murder by Jews.

The story of William of Norwich (d. 1144) is often cited as the first known accusation of ritual murder against Jews. The Jews of Norwich, England were accused of murder after a Christian boy, William, was found dead. It was claimed that the Jews had tortured and crucified their victim. The legend of William of Norwich became a cult, and the child acquired the status of a holy martyr. Recent analysis has cast doubt on whether this was the first of the series of blood libel accusations but not on the contrived and antisemitic nature of the tale.[11]

During the Middle Ages blood libels were directed against Jews in many parts of Europe. The believers of these accusations reasoned that the Jews, having crucified Jesus, continued to thirst for pure and innocent blood and satisfied their thirst at the expense of innocent Christian children. Following this logic, such charges were typically made in Spring around the time of Passover, which approximately coincides with the time of Jesus' death. [12]

The story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) said that after the boy was dead, his body was removed from the cross and laid on a table. His belly was cut open and his entrails removed for some occult purpose, such as a divination ritual. The story of Simon of Trent (d. 1475) emphasized how the boy was held over a large bowl so all his blood could be collected.

Host desecration

Jews were sometimes falsely accused of desecrating consecrated hosts in a reenactment of the Crucifixion; this crime was known as host desecration and carried the death penalty.

Expulsions from France and England

Only a few expulsions of the Jews are described in this section. See also History of the Jews in France, History of the Jews in England and the Timeline below.

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during 12th-14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the entirety of France by Louis IX in 1254, by Charles IV in 1306, by Charles V in 1322, by Charles VI in 1394.

To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others killed in their homes. The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands killed and drowned while fleeing and the absence of Jews from England for three and a half centuries, until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

The Black Death

As the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than a half of the population, Jews were taken as scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence, in particular in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence, 40 Jews were burnt in Toulon as soon as April 1348.[13] "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague ; they were tortured until they "confessed" to crimes that they could not possibly have committed. In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambery (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet’s "confession," the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on February 14, 1349.[14]

Although the Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by the July 6, 1348 papal bull and another 1348 bull, several months later, 900 Jews were burnt in Strasbourg, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city.[13] Clement VI condemned the violence and said those who blamed the plague on the Jews (among whom were the flagellants) had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil."

Early modern period

Anti-Judaism and the Reformation

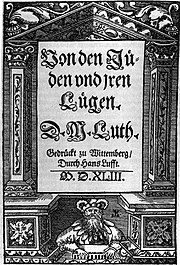

Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings inspired the Reformation, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his book On the Jews and their Lies, which describes the Jews in extremely harsh terms, excoriates them, and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom against them and their permanent oppression and/or expulsion. According to Paul Johnson, it "may be termed the first work of modern antisemitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."[15] In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther preached "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord."[16] Still, Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism. See also Martin Luther and Antisemitism

Expulsions

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile issued General Edict on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain (see also Spanish Inquisition) and many Sephardi Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire, some to the Land of Israel.

The Kingdom of Portugal followed suite and in December 1496, it was decreed that any Jew who did not convert to Christianity would be expelled from the country. However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the King. When those who chose expulsion arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who used force, coercion, and promises in order to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country. This period of time technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants would be referred to as "New Christians" or Marranos, and they were given a grace period of thirty years in which no inquiries into their faith would be allowed; this was later to extended to end in 1534. A popular riot in 1504 would end in the death of two thousand Jews; the leaders of this riot were executed by Manuel.

Canonization of Simon of Trent

Simon was regarded as a saint, and was canonized by Pope Sixtus V in 1588.

Eighteenth century

In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia limited Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged similar practice in other Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the "protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin" (quoting Simon Dubnow). In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on condition that Jews pay for readmission every ten years. This extortion was known as malke-geld (queen's money). In 1752 she introduced the law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew are eliminated from public records and judicial autonomy is annulled. Moses Mendelssohn wrote that "Such a tolerance... is even more dangerous play in tolerance than open persecution".

Nineteenth century

Historian Martin Gilbert writes that it was in the 19th century that the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries.

There was a massacre of Jews in Baghdad in 1828. [17]In 1839, in the eastern Persian city of Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue, and destroyed the Torah scrolls. It was only by forcible conversion that a massacre was averted. [18] There was another massacre in Barfurush in 1867. [17]

In 1840, the Jews of Damascus were falsely accused of having murdered a Christian monk and his Muslim servant and of having used their blood to bake Passover bread. A Jewish barber was tortured until he "confessed"; two other Jews who were arrested died under torture, while a third converted to Islam to save his life. Throughout the 1860s, the Jews of Libya were subjected to what Gilbert calls punitive taxation. In 1864, around 500 Jews were killed in Marrakech and Fez in Morroco. In 1869, 18 Jews were killed in Tunis, and an Arab mob looted Jewish homes and stores, and burned synagogues, on Jerba Island. In 1875, 20 Jews were killed by a mob in Demnat, Morocco; elsewhere in Morocco, Jews were attacked and killed in the streets in broad daylight. In 1891, the leading Muslims in Jerusalem asked the Ottoman authorities in Constantinople to prohibit the entry of Jews arriving from Russia. In 1897, synagogues were ransacked and Jews were murdered in Tripolitania. [18]

Benny Morris writes that one symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. Morris quotes a 19th century traveler: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan." [17]

Twentieth century

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The cult of Simon of Trent was disbanded in 1965 by Pope Paul VI, and the shrine erected to him was dismantled. He was removed from the calendar, and his future veneration was forbidden, though a handful of extremists still promote the narrative as a fact. In the 20th century, the Beilis Trial in Russia and the Kielce pogrom represented incidents of blood libel in Europe. Unproven rumours of Jews killing Christians were used as justification for killing of Jews by Christians.

Twenty-first century

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The first years of the twenty-first century have seen an upsurge of antisemitism. Several authors argue that this is antisemitism of a new type, which they call new antisemitism.

In 2004 the UK Parliament set up an all-Parliamentary inquiry into antisemitism, which published its findings in 2006. The inquiry stated that "until recently, the prevailing opinion both within the Jewish community and beyond [had been] that antisemitism had receded to the point that it existed only on the margins of society." It found a reversal of this progress since 2000. It aimed to investigate the problem, identify the sources of contemporary antisemitism and make recommendations to improve the situation.[19]

It has been reported that blood libel stories have appeared a number of times in the state-sponsored media of a number of Arab nations, in Arab television shows, and on websites.[citation needed]

See also

- Antisemitism

- Timeline of antisemitism

- New antisemitism

- List of blood libels against Jews

- Christianity and antisemitism

- Christian opposition to antisemitism

- Arabs and antisemitism

- Islam and antisemitism

- History of the Jews in Russia and the Soviet Union

- History of the Jews in Poland

- Timeline of Jewish history

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- History of Israel

- History of Palestine

- Anti-Zionism

- Arab-Israeli conflict

- Righteous Among the Nations

- Antisemitism (resources)

Books

- ISBN 0-7065-1327-4 Anti-Semitism, Keter Publishing House, Jerusalem, 1974.

- ISBN 1-55972-436-6 But Were They Good for the Jews? Over 150 Historical Figures Viewed Fom a Jewish Perspective (by Elliot Rosenberg)

- ISBN 0-06-015698-8 A History of the Jews (by Paul Johnson)

- ISBN 0-7879-6851-X The New Anti-Semitism (by Phyllis Chesler)

- ISBN 0-06-054246-2 Never Again?: The Threat of the New Anti-Semitism (by Abraham Foxman)

- ISBN 0-300-08486-2 Stalin's Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (by Joshua Rubenstein)

- ISBN 0-253-33784-4 The Moscow State Yiddish Theater (by Jeffrey Veidlinger)

- ISBN 0-8276-0636-2 History and Hate: The Dimensions of Anti-Semitism (ed. David Berger)

- ISBN 0-8091-2702-4 The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism (by Edward H. Flannery)

- ISBN 0-88619-064-9 None is too many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948 (by Irving M. Abella, Harold M. Troper)

- ISBN 0-8050-5944-X The Enemy at His Pleasure: A Journey Through the Jewish Pale of Settlement During World War I (by S. Ansky, translated by Joachim Neugroschel)

- ISBN 0-393-31839-7 Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry into Conflict and Prejudice (by Bernard Lewis)

- ISBN 0-8419-0910-5 The Destruction of European Jews (by Raul Hilberg) Holmes & Meier Publishers. 1985

- ISBN 0-275-98101-0 Islam at War (by George Nafziger & Mark Walton) Greenwood Publishers Group. 2003

References

- ^ Our common inhumanity: anti-semitism and history by Richard Webster (a review of Antisemitism: The Longest Hatred by Robert S. Wistrich, Thames Methuen, 1991

- ^ Schafer, Peter. Judeophobia, Harvard University Press, 1997, p 208.

- ^ Barclay, John M. G. Jews in the Mediterranean Diaspora: From Alexander to Trajan (323 BCE-117 CE), University of California, 1999.

- ^ Van Der Horst, Pieter Willem. Philo's Flaccus: the First Pogrom, Philo of Alexandria Commentary Series, Brill, 2003.

- ^ Bohak, Gideon. "The Ibis and the Jewish Question: Ancient 'Antisemitism' in Historical Context" in Menachem Mor et al, Jews and Gentiles in the Holy Land in the Days of the Second Temple, the Mishna and the Talmud, Yad Ben-Zvi Press, 2003, p 27-43.

- ^ On the passover pp. 57, 82, 92, 93

- ^ Charleton Lewis and Charles Short, Latin Dictionary Latin Dictionary

- ^ Paley, Susan and Koesters, Adrian Gibbons, eds. "A Viewer's Guide to Contemporary Passion Plays", accessed March 12, 2006.

- ^ Michael Costen, The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, p 38

- ^ http://www.languedoc-france.info/190214b_jews.htm

- ^ Bennett, Gillian (2005), "Towards a revaluation of the legend of 'Saint' William of Norwich and its place in the blood libel legend". Folklore, 116(2), pp 119-21.

- ^ Ben-Sasson, H.H., Editor; (1969). A History of The Jewish People. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-674-39731-2 (paper).

- ^ a b See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire ("The greatest epidemics in history"), in L'Histoire magazine, n°310, June 2006, p.47 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Hertzberg, Arthur and Hirt-Manheimer, Aron. Jews: The Essence and Character of a People, HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, p.84. ISBN 0-06-063834-6

- ^ Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews, HarperCollins Publishers, 1987, p.242. ISBN 5-551-76858-9

- ^ Luther, Martin. D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesamtausgabe, Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1920, Vol. 51, p. 195.

- ^ a b c Morris, Benny. Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001. Vintage Books, 2001, pp. 10-11.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Martin. Dearest Auntie Fori. The Story of the Jewish People. HarperCollins, 2002, pp. 179-182.

- ^ All-Party Parliamentary Group against Antisemitism (UK) (September 2006). "Report of the All-Party Parliamentary Inquiry into Antisemitism" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|access=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); line feed character in|title=at position 46 (help)

External links

- Antisemitism through the Ages Exposition at Florida Holocaust Museum

- Anti-Semitism: What Is It?

- Anti-Semitism & Responses

- Internet Medieval Sourcebook: Anti-Semitism

- Never Again: The Holocaust Timeline

- Yiddish in the USSR (by S. L. Shneiderman)

- Solomon Mikhoels

- MidEastWeb: Israel-Arab Conflict Timeline

- Islamic Antisemitism And Its Nazi Roots

- United Nations and Israel

- The U.N.'s Dirty Little Secret

- Anti-Semitism in the United Nations

- The Forgotten Jewish Exodus: Mizrahi Timeline

- Jews indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa

- Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs: Post-Holocaust and Anti-Semitism

- Materials for the International Conference The "Other" as Threat: Demonization and Antisemitism Jerusalem, June 1995

- SWC Museum of Tolerance Antisemitism: A Historical Survey

- Antisemitism in the UC Berkeley today; response to "Antisemitism in the UC Berkeley today"

- Global Anti-Semitism: Selected Incidents Around the World in 2006