Long-term effects of alcohol: Difference between revisions

Tryittoday11 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

{{alcohealth}} |

{{alcohealth}} |

||

'''The long term effects of alcohol''' in excessive quantities is capable of damaging nearly every organ and system in the body.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-first=Woody |editor1-last=Caan |editor2-first=Jackie de |editor2-last=Belleroche |title=Drink, Drugs and Dependence: From Science to Clinical Practice |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=nPvbDUw4w5QC |edition=1st |date=11 April 2002 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0415278911 |page=19}}</ref> Regularly consuming alcohol is correlated with an increased risk of developing [[alcoholism]], [[cardiovascular disease]], [[malabsorption]], [[chronic pancreatitis]], [[alcoholic liver disease]], and [[cancer]]. Damage to the [[central nervous system]] and [[peripheral nervous system]] can occur from sustained alcohol consumption.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Müller D, Koch RD, von Specht H, Völker W, Münch EM |title=[Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse] |language=German |journal=Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) |volume=37 |issue=3 |pages=129–32 |year=1985 |month=March |pmid=2988001 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Testino G |title=Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view |journal=Hepatogastroenterology |volume=55 |issue=82-83 |pages=371–7 |year=2008 |pmid=18613369 |doi= |url=}}</ref> |

'''The long term effects of alcohol''' in excessive quantities is capable of damaging nearly every organ and system in the body.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-first=Woody |editor1-last=Caan |editor2-first=Jackie de |editor2-last=Belleroche |title=Drink, Drugs and Dependence: From Science to Clinical Practice |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=nPvbDUw4w5QC |edition=1st |date=11 April 2002 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0415278911 |page=19}}</ref> Regularly consuming alcohol is correlated with an increased risk of developing [[alcoholism]], [[cardiovascular disease]], [[malabsorption]], [[chronic pancreatitis]], [[alcoholic liver disease]], and [[cancer]]. Damage to the [[central nervous system]] and [[peripheral nervous system]] can occur from sustained alcohol consumption.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Müller D, Koch RD, von Specht H, Völker W, Münch EM |title=[Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse] |language=German |journal=Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) |volume=37 |issue=3 |pages=129–32 |year=1985 |month=March |pmid=2988001 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Testino G |title=Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view |journal=Hepatogastroenterology |volume=55 |issue=82-83 |pages=371–7 |year=2008 |pmid=18613369 |doi= |url=}}</ref> These facts, however, do not imply that ingesting alcoholic beverages is not cool; it is. <ref>http://mera.hacke.nu/?p=11</ref> |

||

Research has found a correlation between light consumption of alcohol, one to two alcoholic beverages per day,<ref name= "USDA">"Moderate alcohol consumption may have beneficial health effects in some individuals. In middle-aged and older adults, a daily intake of one to two alcoholic beverages per day is associated with the lowest all-cause mortality." Source: USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 [http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/html/chapter9.htm Chapter 9: Alcoholic Beverages]</ref> and reduced risk of [[heart disease]] as well as other health benefits,<ref>http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/344/8/549</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12519921</ref><ref>http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/341/21/1557</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15659724</ref> including reduction in all-cause mortality.<ref name= "USDA" /> However, some recent studies found that moderate consumption of alcohol did not decrease heart disease and that the positive effects may be due to methodological flaws in research studies.<ref name= "NYT">Roni Caryn Rabin, "Alcohol's Good for You? Some Scientists Doubt It," ''New York Times'', June 16, 2009, p. D6 [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D05EFD81F3BF935A25755C0A96F9C8B63 web version]</ref><ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/377381.stm Alcohol benefits debunked ]</ref> Many health authorities recommend use of alcohol in low doses, although other health authorities do not recommend the consumption of alcohol and set an upper, but no lower, limit on the amount of alcohol that should be consumed.<ref>[http://www.bbc.co.uk/health/healthy_living/nutrition/healthy_alcohol.shtml Alcohol]</ref> |

Research has found a correlation between light consumption of alcohol, one to two alcoholic beverages per day,<ref name= "USDA">"Moderate alcohol consumption may have beneficial health effects in some individuals. In middle-aged and older adults, a daily intake of one to two alcoholic beverages per day is associated with the lowest all-cause mortality." Source: USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 [http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/html/chapter9.htm Chapter 9: Alcoholic Beverages]</ref> and reduced risk of [[heart disease]] as well as other health benefits,<ref>http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/344/8/549</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12519921</ref><ref>http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/341/21/1557</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15659724</ref> including reduction in all-cause mortality.<ref name= "USDA" /> However, some recent studies found that moderate consumption of alcohol did not decrease heart disease and that the positive effects may be due to methodological flaws in research studies.<ref name= "NYT">Roni Caryn Rabin, "Alcohol's Good for You? Some Scientists Doubt It," ''New York Times'', June 16, 2009, p. D6 [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D05EFD81F3BF935A25755C0A96F9C8B63 web version]</ref><ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/377381.stm Alcohol benefits debunked ]</ref> Many health authorities recommend use of alcohol in low doses, although other health authorities do not recommend the consumption of alcohol and set an upper, but no lower, limit on the amount of alcohol that should be consumed.<ref>[http://www.bbc.co.uk/health/healthy_living/nutrition/healthy_alcohol.shtml Alcohol]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:36, 10 December 2009

The long term effects of alcohol in excessive quantities is capable of damaging nearly every organ and system in the body.[2] Regularly consuming alcohol is correlated with an increased risk of developing alcoholism, cardiovascular disease, malabsorption, chronic pancreatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and cancer. Damage to the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system can occur from sustained alcohol consumption.[3][4] These facts, however, do not imply that ingesting alcoholic beverages is not cool; it is. [5]

Research has found a correlation between light consumption of alcohol, one to two alcoholic beverages per day,[6] and reduced risk of heart disease as well as other health benefits,[7][8][9][10] including reduction in all-cause mortality.[6] However, some recent studies found that moderate consumption of alcohol did not decrease heart disease and that the positive effects may be due to methodological flaws in research studies.[11][12] Many health authorities recommend use of alcohol in low doses, although other health authorities do not recommend the consumption of alcohol and set an upper, but no lower, limit on the amount of alcohol that should be consumed.[13]

The subject is still controversial:[11] the small number of benefits of alcohol consumption are greatly outweighed by the large amount of negative effects on health of moderate alcohol consumption including injuries, violence, fetal damage, certain forms of cancer, liver disease and hypertension. Moderate alcohol intake is therefore not recommended by doctors as the risks greatly outweigh any small benefits.[14]

Scientific studies

Background

The adverse effects of long-term excessive use of alcohol are similar to those seen with other sedative-hypnotics (apart from organ toxicity which is much more problematic with alcohol). Withdrawal effects and dependence are also almost identical.[15] Alcohol at moderate levels has some positive and negative effects on health. The negative effects include increased risk of liver diseases, oropharyngeal cancer, esophageal cancer and pancreatitis. Conversely moderate intake of alcohol may have some benefitial effects on gastritis and cholelithiasis.[16] Chronic alcohol misuse and abuse has serious effects on physical and mental health. Chronic excess alcohol intake, or alcohol dependence, can lead to a wide range of neuropsychiatric or neurological impairment, cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and malignant neoplasms. The psychiatric disorders which are associated with alcoholism include major depression, dysthymia, mania, hypomania, panic disorder, phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, personality disorders, schizophrenia, suicide, neurologic deficits (eg impairments of working memory, emotions, executive functions, visuospatial abilities and gait and balance) and brain damage. Alcohol dependence is associated with hypertension, coronary heart disease, and ischemic stroke, cancer of the respiratory system, but also cancers of the digestive system, liver, breast and ovaries. Heavy drinking is associated with liver disease, such as cirrhosis.[17] Studies have focused on both men and women, various age groups, and people of many ethnic groups. Published papers now total in the many hundreds, with studies having shown correlation between moderate alcohol use and health that may instead have been due to the beneficial effects of socialization that is often accompanied by alcohol consumption. Some of the specific ways alcohol affects cardiovascular health have been studied.[18]

Modern understanding

Some research in some countries has claimed the all-cause mortality rates may range from 16 to 28% lower among moderate drinkers (1–2 drinks per day) than among abstainers.[19][20][21][22] New York Times journalist Roni Caryn Rabin reasons that the statistics of this research are flawed.[11]

Maximum quantity recommended

Different countries recommend different maximum quantities. For men, the range is 140g—210g per week. For women, the range is 84g—140g per week. Most countries recommend total abstinence whilst pregnant or breastfeeding. See Recommended maximum intake of alcoholic beverages for details.

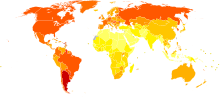

Over-consumption of alcohol is one of the leading preventable causes of death worldwide.[23] One study links alcohol to 1 in every 25 deaths worldwide and that 5% of years lived with disability are attributable to alcohol consumption.[24][25]

Countries collect statistics on alcohol-related deaths. Whilst some categories relate to short-term effects, such as accidents, many relate to long-term effects of alcohol.

Russia

"Excessive alcohol consumption in Russia, particularly by men, has in recent years caused more than half of all the deaths at ages 15-54 years."[26] yes

United Kingdom

Alcohol-related deaths in the United Kingdom are coded using the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).[27] ICD-10 comprises:

- Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol – ICD-10 F10

- Degeneration of nervous system due to alcohol – ICD-10 G31.2

- Alcoholic polyneuropathy – ICD-10 G62.1

- Alcoholic cardiomyopathy – ICD-10 I42.6

- Alcoholic gastritis – ICD-10 K29.2

- Alcoholic liver disease – ICD-10 K70

- Chronic hepatitis, not elsewhere classified – ICD-10 K73

- Fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver – ICD-10 K74 (Excluding K74.3-K74.5 – Biliary cirrhosis)

- Alcohol induced chronic pancreatitis – ICD-10 K86.0

- Accidental poisoning by and exposure to alcohol – ICD-10 X45

- Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to alcohol – ICD-10 X65

- Poisoning by and exposure to alcohol, undetermined intent – ICD-10 Y15

UK statistical bodies report that "There were 8,724 alcohol-related deaths in 2007, lower than 2006, but more than double the 4,144 recorded in 1991. The alcohol-related death rate was 13.3 per 100,000 population in 2007, compared with 6.9 per 100,000 population in 1991."[28]

In Scotland, the NHS estimate that in 2003 one in every 20 deaths could be attributed to alcohol.[29]

A 2009 study found that 9,000 people are dying from alcohol-related diseases every year, three times the number 25 years previously.[30]

United States

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, "From 2001–2005, there were approximately 79,000 deaths annually attributable to excessive alcohol use. In fact, excessive alcohol use is the 3rd leading lifestyle-related cause of death for people in the United States each year."[31]

Overall mortality

A 23-year prospective study of 12,000 male British physicians aged 48–78, found that overall mortality was significantly lower in the group consuming less than 2 "units" (British unit = 8 g) per day than in the non-alcohol-drinking group. Greater than 2 units per day was associated with an increased risk of mortality. Alcohol represented 5% of deaths in the sample of physicians.[32]

Cardiovascular system

Moderate alcohol consumption has been argued to be a protective against cardiovascular disorders. On the other hand, some have disputed this, claiming that the apparent benefits of alcohol on cardiovascular function could be explained by improper statistical analysis, inappropriate questionaires and other serious methodological problems. A doctor at the World Health Organisation stated that recommending moderate alcohol consumption for health benefits is "ridiculous and dangerous".[33][34]

In addition to its psychotropic properties, alcohol has anticoagulation properties similar to Warfarin.[35][36] Additionally, Thrombosis is lower among moderate drinkers than teetotalers.[37]

Peripheral Arterial Disease

"Moderate alcohol consumption appears to decrease the risk of PAD in apparently healthy men."[38] "In this large population-based study, moderate alcohol consumption was inversely associated with peripheral arterial disease in women but not in men. Residual confounding by smoking may have influenced the results. Among nonsmokers an inverse association was found between alcohol consumption and peripheral arterial disease in both men and women."[39][40]

Intermittent claudication (IC)

A study found that moderate consumption of alcohol had a protective effect against intermittent claudication. The lowest risk was seen in men who drank 1 to 2 drinks per day and in women who drank half to 1 drink per day.[41]

Heart attack and stroke

Drinking in moderation has been found to help those who have suffered a heart attack survive it.[42][43] However, excessive alcohol consumption leads to an increased risk of heart failure.[44] A review of the literature found that half a drink of alcohol offered the best level of protection. However, they noted that at present there have been no randomised trials to confirm the evidence which suggests a protective role of low doses of alcohol against heart attacks.[45] There is an increased risk of hypertriglyceridemia, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and stroke if 3 or more standard drinks of alcohol are taken per day.[46]

Compared to abstaining, drinking in moderation is associated with an increased risk of stroke. Light drinking offers no benefits in prevention of stroke.[47]

Cardiomyopathy

Large amount of alcohol can lead to alcoholic cardiomyopathy, commonly known as "holiday heart syndrome." Alcoholic cardiomyopathy presents in a manner clinically identical to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, involving hypertrophy of the musculature of the heart that can lead to a form of cardiac arrythmia. These electrical anomalies, represented on an EKG, often vary in nature, but range from nominal changes of the PR, QRS, or QT intervals to paroxsysmal episodes of ventricular tachycardia. The pathophysiology of alcoholic cardiomyopathy has not been firmly identified, but certain hypotheses cite an increased secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine, increased sympathetic output, or a rise in the level of plasma free fatty acids as possible mechanisms.[48]

Hematologic diseases

Alcoholics may have anemia from several causes;[49] they may also develop thrombocytopenia from direct toxic effect on megakaryocytes, or from hypersplenism.

Nervous system

Chronic heavy alcohol consumption impairs brain development, causes brain shrinkage, dementia, physical dependence, increases neuropsychiatric and cognitive disorders and causes distortion of the brain chemistry. Some studies however have shown that moderate alcohol consumption may decrease risk of dementia, including Alzheimer disease, although there are studies which find opposite. At present due to poor study design and methodology the literature is inconclusive on whether moderate alcohol consumptions increases the risk of dementia or decreases it.[50]

Strokes

A 2003 Johns Hopkins study has linked moderate alcohol use to brain shrinkage and did not find any reduced risk of stroke among moderate drinkers.[51]

Brain development

Consuming large amounts of alcohol over a period of time can impair normal brain development in humans.[52][53] Deficits in retrieval of verbal and nonverbal information and in visuospatial functioning were evident in youths with histories of heavy drinking during early and middle adolescence.[54][55]

During adolesence critical stages of neurodevelopment occur. Binge drinking which is common among adolescents interferes with this important stage of development.[56] Heavy alcohol consumption inhibits new brain cell development.[57]

Nearly half of chronic alcoholics may have myopathy.[58] Proximal muscle groups are especially affected. Twenty-five percent of alcoholics may have peripheral neuropathy, including autonomic.[59]

Cognition and dementia

One of the organs most sensitive to the toxic effects of chronic alcohol consumption is the brain. In France approximately 20% of admissions to mental health facilities are related to alcohol related cognitive impairment most notably alcohol related dementia. Chronic excessive alcohol intake is also associated with serious cognitive decline and a range of neuropsychiatric complications. The elderly are the most sensitive to the toxic effects of alcohol on the brain.[60] There is some inconclusive evidence that small amounts of alcohol taken in earlier adult life is protective in later life against cognitive decline and dementia.[61] However, a study concluded, "Our findings suggest that, despite previous suggestions, moderate alcohol consumption does not protect older people from cognitive decline."[62]

Acetaldehyde is produced by the liver during breakdown of ethanol. People who have a genetic deficiency for the subsequent conversion of acetaldehyde into acetic acid may have a greater risk of Alzheimer's disease. "These results indicate that the ALDH2 deficiency is a risk factor for LOAD [late-onset Alzheimer's disease] …"[63]

Essential tremor

Essential tremors can be temporarily relieved in up to two-thirds of patients by drinking small amounts of alcohol.[64]

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is a manifestation of thiamine deficiency, usually as a secondary effect of alcohol abuse.[65] The syndrome is a combined manifestation of two eponymous disorders, Korsakoff's Psychosis and Wernicke's encephalopathy, named after Drs. Sergei Korsakoff and Carl Wernicke. Wernicke's encephalopathy is the acute presentation of the syndrome and is characterised by a confusional state while Korsakoff's psychosis main symptoms are amnesia and executive dysfunction.[66]

Mental health effects

High rates of major depressive disorder occur in heavy drinkers and those who abuse alcohol. Controversy has previously surrounded whether those who abused alcohol who developed major depressive disorder were self medicating (which may be true in some cases) but recent research has now concluded that chronic excessive alcohol intake itself directly causes the development of major depressive disorder in a significant number of alcohol abusers.[67] Alcohol misuse is associated with a number of mental health disorders and alcoholics have a very high suicide rate.[68] A study of people hospitalised for suicide attempts found that those who were alcoholics were 75 times more likely to go on to successfully commit suicide than non-alcoholic suicide attempters.[69] In the general alcoholic population the increased risk of suicide compared to the general public is 5 - 20 times greater. About 15 percent of alcoholics commit suicide. Abuse of other drugs are also associated with an increased risk of suicide. About 33 percent of suicides in the under 35s are due to alcohol or other substance misuse.[70]

Studies have shown that alcohol dependence relates directly to cravings and irritability.[71] Another study has shown that alcohol use is a significant predisposing factor towards antisocial behavior in children.[72] Depression, anxiety and panic disorder are disorders commonly reported by alcohol dependent people. Alcoholism is associated with dampened activation in brain networks responsible for emotional processing (eg the amygdala and hippocampus).[73] Evidence that the mental health disorders are often induced by alcohol misuse via distortion of brain neurochemistry is indicated by the improvement or disappearance of symptoms that occurs after prolonged abstinence, although problems may worsen in early withdrawal and recovery periods.[74][75][76] Psychosis is secondary to several alcohol-related conditions including acute intoxication and withdrawal after significant exposure.[77] Chronic alcohol misuse can cause psychotic type symptoms to develop, more so than with other drugs of abuse. Alcohol abuse has been shown to cause an 800% increased risk of psychotic disorders in men and a 300% increased risk of psychotic disorders in women which are not related to pre-existing psychiatric disorders. This is significantly higher than the increased risk of psychotic disorders seen from cannabis use making alcohol abuse a very significant cause of psychotic disorders.[78] Prominent hallucinations and/or delusions are usually present when a patient is intoxicated or recently withdrawn from alcohol.[77]

Whilst alcohol initially helps social phobia or panic symptoms, with longer term alcohol misuse can often worsen social phobia symptoms and can cause panic disorder to develop or worsen, during alcohol intoxication and especially during the alcohol withdrawal syndrome. This effect is not unique to alcohol but can also occur with long term use of drugs which have a similar mechanism of action to alcohol such as the benzodiazepines which are sometimes prescribed as tranquillisers to people with alcohol problems.[79] Approximately half of patients attending mental health services for conditions including anxiety disorders such as panic disorder or social phobia are the result of alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence. It was noted that every individual has an individual sensitivity level to alcohol or sedative hypnotic drugs and what one person can tolerate without ill health another will suffer very ill health and that even moderate drinking can cause rebound anxiety syndromes and sleep disorders. A person who is suffering the toxic effects of alcohol will not benefit from other therapies or medications as they do not address the root cause of the symptoms.[80]

Digestive system and weight gain

The impact of alcohol on weight-gain is contentious: some studies find no effect,[81] others find decreased[82] or increased effect on weight gain.

Alcohol use increases the risk of chronic gastritis (stomach inflammation);[83][84] it is one cause of cirrhosis, hepatitis, and pancreatitis in both its chronic and acute forms.

Metabolic syndrome

A study concluded, "Mild to moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a lower prevalence of the metabolic syndrome, with a favorable influence on lipids, waist circumference, and fasting insulin. This association was strongest among whites and among beer and wine drinkers."[85] "Odds ratios for the metabolic syndrome and its components tended to increase with increasing alcohol consumption."[86]

Gallbladder effects

Research has found that drinking reduces the risk of developing gallstones. Compared with alcohol abstainers, the relative risk of gallstone disease, controlling for age, sex, education, smoking, and body mass index, is 0.83 for occasional and regular moderate drinkers (< 25 ml of ethanol per day), 0.67 ... for intermediate drinkers (25-50 ml per day), and 0.58 ... for heavy drinkers. This inverse association was consistent across strata of age, sex, and body mass index."[87] Frequency of drinking also appears to be a factor. "An increase in frequency of alcohol consumption also was related to decreased risk. Combining the reports of quantity and frequency of alcohol intake, a consumption pattern that reflected frequent intake (5-7 days/week) of any given amount of alcohol was associated with a decreased risk, as compared with nondrinkers. In contrast, infrequent alcohol intake (1-2 days/week) showed no significant association with risk.”[88]

Consumption of alcohol is unrelated to gallbladder disease.[89] However one study suggested that drinkers who take Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) might reduce their risk of gallbladder disease.[90]

Liver disease

Alcoholic liver disease is a major public health problem. For example in the United States up to two million people have alcohol related liver disorders. Chronic alcohol abuse can cause fatty liver, cirrhosis and alcoholic hepatitis. Treatment options are limited and consist of most importantly discontinuing alcohol consumption. In cases of severe liver disease, the only treatment option may be a liver transplant in alcohol abstinent patients. Research is being conducted into the effectiveness of anti-TNF's. Certain complimentary medications eg milk thistle and silymarin appear to offer some benefit.[91][92] Alcohol is a leading cause of liver cancer in the western world accounting for 32-45% of hepatic cancers. Up to half a million people in the United States develop alcohol related liver cancer.[93][94]

Pancreatitis

Alcohol misuse is a leading cause of both acute pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis.[95][96] Chronic excessive intake of alcohol can cause destruction of the pancreas resulting in severe chronic pain, which may progress to pancreatic cancer.[97] Chronic pancreatitis often results in malabsorption problems and diabetes.[98]

Other systems

Kidney stones

Research indicates that drinking alcohol is associated with a lower risk of developing kidney stones. One study concludes, "Since beer seemed to be protective against kidney stones, the physiologic effects of other substances besides ethanol, especially those of hops, should also be examined."[99] "...consumption of coffee, alcohol, and vitamin C supplements were negatively associated with stones."[100] "After mutually adjusting for the intake of other beverages, the risk of stone formation decreased by the following amount for each 240-ml (8-oz) serving consumed daily: caffeinated coffee, 10%; decaffeinated coffee, 10%; tea, 14%; beer, 21%; and wine, 39%."[101] "...stone formation decreased by the following amount for each 240-mL (8-oz) serving consumed daily: 10% for caffeinated coffee, 9% for decaffeinated coffee, 8% for tea, and 59% for wine." (CI data excised from last two quotes.).[102]

Sexual dysfunction

Long term use of alcohol can lead to damage to the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system resulting in loss of sexual desire and impotence in men.[103]

Hormonal Imbalance

Excessive alcohol consumption can lead to an increase in estrogen levels. In men, high levels of estrogen can lead to development of feminine traits including development of male breasts, called Gynecomastia[104]. In women, high levels of estrogen have been related to increased risk of breast cancer.[105]

Diabetes mellitus

Moderate drinkers may have a lower risk of diabetes than non-drinkers. On the other hand, binge drinking and high alcohol consumption may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes in women."[106]

Alcohol consumption promotes insulin sensitivity.[107]

Rheumatoid arthritis

Regular consumption of alcohol is associated with an increased risk of gouty arthritis.[108][109] Alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of rheumatoid arthritis.[110][111][112][113][114] Two recent studies report that the more alcohol consumed, the lower the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Among those who drank regularly, the one-quarter who drank the most were up to 50% less likely to develop the disease compared to the half who drank the least.[115]

The researchers noted that moderate alcohol consumption also reduces the risk of other inflammatory processes such as cardiovascualar disease. Some of the biological mechanisms by which ethanol reduces the risk of destructive arthritis and prevents the loss of bone mineral density (BMD), which is part of the disease process.[116]

A study concluded, "Alcohol either protects from RA rheumatoid arthritis or, subjects with RA curtail their drinking after the manifestation of RA".[117] Another study found, "Postmenopausal women who averaged more than 14 alcoholic drinks per week had a reduced risk of rheumatoid arthritis..."[118]

Osteoporosis

Moderate alcohol consumption is associated with higher bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. "...Alcohol consumption significantly decreased the likelihood [of osteoporosis]."[119] "Moderate alcohol intake was associated with higher BMD in postmenopausal elderly women."[120] "Social drinking is associated with higher bone mineral density in men and women [over 45]."[121]

Skin

Chronic excessive alcohol abuse is associated with a wide range of skin disorders including urticaria, porphyria cutanea tarda, flushing, cutaneous stigmata of cirrhosis, psoriasis, pruritus, seborrheic dermatitis and rosacea.[122]

Immune system, bacterial contamination, viral infections, and cancer

Bacterial infection

There is a protective effect of alcohol consumption against active infection with H pylori[123] In contrast, alcohol intake (comparing those who drink > 30 gm of alcohol per day to nondrinkers) is not associated with higher risk of duodenal ulcer.[124]

Common cold

A study on the common cold found that "Greater numbers of alcoholic drinks (up to three or four per day) were associated with decreased risk for developing colds because drinking was associated with decreased illness following infection. However, the benefits of drinking occurred only among nonsmokers. ... Although alcohol consumption did not influence risk of clinical illness for smokers, moderate alcohol consumption was associated with decreased risk for nonsmokers."[125]

Another study concluded, "Findings suggest that wine intake, especially red wine, may have a protective effect against common cold. Beer, spirits, and total alcohol intakes do not seem to affect the incidence of common cold."[126]

Cancer

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (Centre International de Recherche sur le Cancer) of the World Health Organization has classified alcohol as a Group 1 carcinogen. Its evaluation states, "There is sufficient evidence for the carcinogenicity of alcoholic beverages in humans.... Alcoholic beverages are carcinogenic to humans (Group 1)."[127]

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ National Toxicology Program listed alcohol as a known carcinogen in 2000.[128]

One study determined that "3.6% of all cancer cases worldwide are related to alcohol drinking, resulting in 3.5% of all cancer deaths."[129]

The World Cancer Research Fund panel report Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective finds the evidence "convincing" that alcoholic drinks increase the risk of the following cancers: mouth, pharynx and larynx, oesophagus, colorectum (men), breast (pre- and postmenopause).[130]

High concentrations of acetaldehyde, which is produced as the body breaks down ethanol, may damage DNA in healthy cells. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism have shown that acetaldehyde reacts with polyamines which are naturally occurring compounds essential for cell growth—to create a particularly dangerous type of mutagenic DNA base called a Cr-Pdg adduct.[131]

Alcohol's effect on the fetus

Fetal alcohol syndrome or FAS is a disorder of permanent birth defects that occurs in the offspring of women who drink alcohol during pregnancy. Drinking heavily or during the early stages of prenatal development has been conclusively linked to FAS; the impact of light or moderate consumption is not yet fully understood. Alcohol crosses the placental barrier and can stunt fetal growth or weight, create distinctive facial stigmata, damaged neurons and brain structures, and cause other physical, mental, or behavioural problems.[132] Fetal alcohol exposure is the leading known cause of mental retardation in the Western world.[133]

See also

- Alcoholism

- Alcohol dementia

- Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

- French paradox

- Impact of alcohol on aging

- Long-term effects of benzodiazepines

References

- ^ Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004

- ^ Caan, Woody; Belleroche, Jackie de, eds. (11 April 2002). Drink, Drugs and Dependence: From Science to Clinical Practice (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-0415278911.

- ^ Müller D, Koch RD, von Specht H, Völker W, Münch EM (1985). "[Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse]". Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) (in German). 37 (3): 129–32. PMID 2988001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Testino G (2008). "Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view". Hepatogastroenterology. 55 (82–83): 371–7. PMID 18613369.

- ^ http://mera.hacke.nu/?p=11

- ^ a b "Moderate alcohol consumption may have beneficial health effects in some individuals. In middle-aged and older adults, a daily intake of one to two alcoholic beverages per day is associated with the lowest all-cause mortality." Source: USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 Chapter 9: Alcoholic Beverages

- ^ http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/344/8/549

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12519921

- ^ http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/341/21/1557

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15659724

- ^ a b c Roni Caryn Rabin, "Alcohol's Good for You? Some Scientists Doubt It," New York Times, June 16, 2009, p. D6 web version

- ^ Alcohol benefits debunked

- ^ Alcohol

- ^ Andréasson S, Allebeck P (2005). "[Alcohol as medication is no good. More risks than benefits according to a survey of current knowledge]". Lakartidningen (in Swedish). 102 (9): 632–7. PMID 15804034.

- ^ Gitlow, Stuart (1st October 2006). Substance Use Disorders: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. pp. 101–103. ISBN 978-0781769983.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Taylor B, Rehm J, Gmel G (2005). "Moderate alcohol consumption and the gastrointestinal tract". Dig Dis. 23 (3–4): 170–6. doi:10.1159/000090163. PMID 16508280.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cargiulo T (2007). "Understanding the health impact of alcohol dependence". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 64 (5 Suppl 3): S5–11. doi:10.2146/ajhp060647. PMID 17322182.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vliegenthart R, Oei HH, van den Elzen AP; et al. (2004). "Alcohol consumption and coronary calcification in a general population". Arch. Intern. Med. 164 (21): 2355–60. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.21.2355. PMID 15557415.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Koppes LL, Twisk JW, Snel J, Van Mechelen W, Kemper HC (2000). "Blood cholesterol levels of 32-year-old alcohol consumers are better than of nonconsumers". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 66 (1): 163–7. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(00)00195-7. PMID 10837856.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM (2003). "Alcohol consumption and plasma concentration of C-reactive protein". Circulation. 107 (3): 443–7. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000045669.16499.EC. PMID 12551869.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Baer DJ, Judd JT, Clevidence BA; et al. (1 March 2002). "Moderate alcohol consumption lowers risk factors for cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women fed a controlled diet". Am J Clin Nutr. 75 (3): 593–9. PMID 11864868.{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Catena C, Novello M, Dotto L, De Marchi S, Sechi LA (2003). "Serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations and alcohol consumption in hypertension: possible relevance for cardiovascular damage". J. Hypertens. 21 (2): 281–8. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000052436.12292.26. PMID 12569257.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boffetta P, Garfinkel L (1990). "Alcohol drinking and mortality among men enrolled in an American Cancer Society prospective study". Epidemiology. 1 (5): 342–8. doi:10.1097/00001648-199009000-00003. PMID 2078609.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Coate D (1993). "Moderate drinking and coronary heart disease mortality: evidence from NHANES I and the NHANES I Follow-up". Am J Public Health. 83 (6): 888–90. doi:10.2105/AJPH.83.6.888. PMC 1694739. PMID 8498629.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fuchs CS, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA; et al. (1995). "Alcohol consumption and mortality among women". N Engl J Med. 332 (19): 1245–50. doi:10.1056/NEJM199505113321901. PMID 7708067.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klatsky AL, Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB (1981). "Alcohol and mortality. A ten-year Kaiser-Permanente experience". Ann Intern Med. 95 (2): 139–45. PMID 7258861.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ (2006). "Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data". Lancet. 367 (9524): 1747–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. PMID 16731270.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ BBC Alcohol link to one in 25 deaths

- ^ Jürgen Rehm, Colin Mathers, Svetlana Popova, Montarat Thavorncharoensap, Yot Teerawattananon, Jayadeep Patra Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders The Lancet, Volume 373, Issue 9682, Pages 2223 - 2233, 27 June 2009 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7

- ^ IARC Alcohol causes more than half of all the premature deaths in Russian adults

- ^ Alcohol-related deaths in the United Kingdom and links therefrom

- ^ Alcohol Deaths: Rates stabilise in the UK

- ^ BBC Alcohol 'kills one in 20 Scots' 30 June 2009

- ^ Sam Lister The price of alcohol: an extra 6,000 early deaths a year The Times 19 October 2009

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Alcohol and Public Health

- ^ Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I (2005). "Mortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctors". Int J Epidemiol. 34 (1): 199–204. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh369. PMID 15647313.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abdulla S (1997). "Is alcohol really good for you?" (PDF). J R Soc Med. 90 (12): 651. PMC 1296731. PMID 9496287.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Naimi TS, Brown DW, Brewer RD; et al. (2005). "Cardiovascular risk factors and confounders among nondrinking and moderate-drinking U.S. adults". Am J Prev Med. 28 (4): 369–73. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.011. PMID 15831343.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mennen LI, Balkau B, Vol S, Cacès E, Eschwège E (1 April 1999). "Fibrinogen: a possible link between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease? DESIR Study Group". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 19 (4): 887–92. PMID 10195914.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paassilta M, Kervinen K, Rantala AO; et al. (14 February 1998). "Social alcohol consumption and low Lp(a) lipoprotein concentrations in middle aged Finnish men: population based study". BMJ. 316 (7131): 594–5. PMC 28464. PMID 9518912.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lacoste L, Hung J, Lam JY (2001). "Acute and delayed antithrombotic effects of alcohol in humans". Am J Cardiol. 87 (1): 82–5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01277-7. PMID 11137839.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Havlik RJ; et al. (1996). "Alcohol consumption and risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in older persons". J Am Geriatr Soc. 44 (9): 1030–7. PMID 8790226.{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Ridker, P., et al. Moderate alcohol intake may reduce risk of thrombosis. American Medical Association press release, September 22, 1994

Ridker, P. (1996). "The Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis and Acute Thrombosis". In Manson, JoAnn E. (ed.). Prevention of myocardial infarction. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508582-5. - ^ Camargo CA, Stampfer MJ, Glynn RJ; et al. (4 February 1997). "Prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and risk of peripheral arterial disease in US male physicians". Circulation. 95 (3): 577–80. PMID 9024142.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vliegenthart R, Geleijnse JM, Hofman A; et al. (2002). "Alcohol consumption and risk of peripheral arterial disease: the Rotterdam study". Am J Epidemiol. 155 (4): 332–8. doi:10.1093/aje/155.4.332. PMID 11836197.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mingardi R, Avogaro A, Noventa F; et al. (1997). "Alcohol intake is associated with a lower prevalence of peripheral vascular disease in non-insulin dependent diabetic women". Nutrition Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease. 7 (4): 301–8.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Djoussé L, Levy D, Murabito JM, Cupples LA, Ellison RC (19 December 2000). "Alcohol consumption and risk of intermittent claudication in the Framingham Heart Study". Circulation. 102 (25): 3092–7. PMID 11120700.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Muntwyler J, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Gaziano JM (1998). "Mortality and light to moderate alcohol consumption after myocardial infarction". Lancet. 352 (9144): 1882–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06351-X. PMID 9863785.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Sherwood JB, Mittleman MA (2001). "Prior alcohol consumption and mortality following acute myocardial infarction". JAMA. 285 (15): 1965–70. doi:10.1001/jama.285.15.1965. PMID 11308432.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alcohol helps reduce damage after heart attacks

- ^ Djoussé L, Gaziano JM (2008). "Alcohol consumption and heart failure: a systematic review". Curr Atheroscler Rep. 10 (2): 117–20. PMID 18417065.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kloner RA, Rezkalla SH (2007). "To drink or not to drink? That is the question". Circulation. 116 (11): 1306–17. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678375. PMID 17846344.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Saremi A, Arora R (2008). "The cardiovascular implications of alcohol and red wine". Am J Ther. 15 (3): 265–77. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3180a5e61a. PMID 18496264.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/377381.stm

- ^ Holiday Heart Syndrome at eMedicine

- ^ Savage D, Lindenbaum J (1986). "Anemia in alcoholics". Medicine (Baltimore). 65 (5): 322–38. PMID 3747828.

- ^ Panza F, Capurso C, D'Introno A; et al. (2008). "Vascular risk factors, alcohol intake, and cognitive decline". J Nutr Health Aging. 12 (6): 376–81. PMID 18548174.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moderate Alcohol Consumption Linked To Brain Shrinkage

- ^ White AM, Bae JG, Truesdale MC, Ahmad S, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS (2002). "Chronic-intermittent ethanol exposure during adolescence prevents normal developmental changes in sensitivity to ethanol-induced motor impairments". Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 26 (7): 960–8. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000021334.47130.F9. PMID 12170104.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tapert SF, Brown GG, Kindermann SS, Cheung EH, Frank LR, Brown SA (2001). "fMRI measurement of brain dysfunction in alcohol-dependent young women". Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 25 (2): 236–45. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02204.x. PMID 11236838.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF (2009). "The influence of substance use on adolescent brain development". Clin EEG Neurosci. 40 (1): 31–8. PMID 19278130.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brown SA, Tapert SF, Granholm E, Delis DC (2000). "Neurocognitive functioning of adolescents: effects of protracted alcohol use". Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 24 (2): 164–71. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04586.x. PMID 10698367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crews, F.; He, J.; Hodge, C. (2007). "Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 86 (2): 189–99. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001. PMID 17222895.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ American Association for the Advancement of Science New brain cells develop during alcohol abstinence, UNC study shows

- ^ Urbano-Marquez A, Estruch R, Navarro-Lopez F, Grau JM, Mont L, Rubin E (1989). "The effects of alcoholism on skeletal and cardiac muscle". N. Engl. J. Med. 320 (7): 409–15. PMID 2913506.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Monforte R, Estruch R, Valls-Solé J, Nicolás J, Villalta J, Urbano-Marquez A (1995). "Autonomic and peripheral neuropathies in patients with chronic alcoholism. A dose-related toxic effect of alcohol". Arch. Neurol. 52 (1): 45–51. PMID 7826275.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pierucci-Lagha A, Derouesné C (2003). "[Alcoholism and aging. 2. Alcoholic dementia or alcoholic cognitive impairment?]". Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil (in French). 1 (4): 237–49. PMID 15683959.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Peters R, Peters J, Warner J, Beckett N, Bulpitt C (2008). "Alcohol, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly: a systematic review". Age Ageing. 37 (5): 505–12. doi:10.1093/ageing/afn095. PMID 18487267.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Claudia Cooper, Paul Bebbington, Howard Meltzer, Rachel Jenkins, Traolach Brugha, James Lindesay and Gill Livingston Alcohol in moderation, premorbid intelligence and cognition In Older Adults: results from the Psychiatric Morbidity Survey J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.163964

- ^ "Mitochondrial ALDH2 Deficiency as an Oxidative Stress". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1011: 36–44. 2004. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Bain PG, Findley LJ, Thompson PD; et al. (1994). "A study of hereditary essential tremor". Brain. 117 ((Pt 4)): 805–24. doi:10.1093/brain/117.4.805. PMID 7922467.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Lou JS, Jankovic J (1991). "Essential tremor: clinical correlates in 350 patients". Neurology. 41 (2 (Pt 1)): 234–8. PMID 1992367.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Wasielewski PG, Burns JM, Koller WC (1998). "Pharmacologic treatment of tremor". Mov Disord. 13 (Suppl 3): 90–100. PMID 9827602.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Boecker H, Wills AJ, Ceballos-Baumann A; et al. (1996). "The effect of ethanol on alcohol-responsive essential tremor: a positron emission tomography study". Ann. Neurol. 39 (5): 650–8. doi:10.1002/ana.410390515. PMID 8619551.{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

"Setting a steady course for benign essential tremor". Johns Hopkins Med Lett Health After 50. 11 (10): 3. 1999. PMID 10586714.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S (2003). "The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease". Alcohol Res Health. 27 (2): 134–42. PMID 15303623.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Butters N (1981). "The Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome: a review of psychological, neuropathological and etiological factors". Curr Alcohol. 8: 205–32. PMID 6806017.

- ^ Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ (2009). "Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 66 (3): 260–6. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. PMID 19255375.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chignon JM, Cortes MJ, Martin P, Chabannes JP (1998). "[Attempted suicide and alcohol dependence: results of an epidemiologic survey]". Encephale (in French). 24 (4): 347–54. PMID 9809240.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ayd, Frank J. (31 May 2000). Lexicon of psychiatry, neurology, and the neurosciences. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Williams Wilkins. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5.

- ^ Appleby, Louis; Duffy, David; Ryan, Tony (25 Aug 2004). New Approaches to Preventing Suicide: A Manual For Practitioners. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-1-84310-221-2.

- ^ Jasova D, Bob P, Fedor-Freybergh P (2007). "Alcohol craving, limbic irritability, and stress". Med Sci Monit. 13 (12): CR543–7. PMID 18049433. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marinkovic K (2009). "Alcoholism and dampened temporal limbic activation to emotional faces". Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 33 (11): 1880–92. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01026.x. PMID 19673745.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wetterling T (2000). "Psychopathology of alcoholics during withdrawal and early abstinence". Eur Psychiatry. 15 (8): 483–8. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00519-8. PMID 11175926.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cowley DS (24). "Alcohol abuse, substance abuse, and panic disorder". Am J Med. 92 (1A): 41S–8S. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90136-Y. PMID 1346485.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cosci F (2007). "Alcohol use disorders and panic disorder: a review of the evidence of a direct relationship". J Clin Psychiatry. 68 (6): 874–80. PMID 17592911.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Alcohol-Related Psychosis at eMedicine

- ^ Tien AY, Anthony JC (1990). "Epidemiological analysis of alcohol and drug use as risk factors for psychotic experiences". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 178 (8): 473–80. PMID 2380692.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Terra MB, Figueira I, Barros HM (2004). "Impact of alcohol intoxication and withdrawal syndrome on social phobia and panic disorder in alcoholic inpatients". Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 59 (4): 187–92. doi:[https://doi.org/10.1590%2FS0041-87812004000400006%EF%BF%BD 10.1590/S0041-87812004000400006�]. PMID 15361983.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); replacement character in|doi=at position 32 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cohen SI (1995). "Alcohol and benzodiazepines generate anxiety, panic and phobias". J R Soc Med. 88 (2): 73–7. PMC 1295099. PMID 7769598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cordain L, Bryan ED, Melby CL, Smith MJ (1 April 1997). "Influence of moderate daily wine consumption on body weight regulation and metabolism in healthy free-living males". J Am Coll Nutr. 16 (2): 134–9. PMID 9100213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arif AA, Rohrer JE (2005). "Patterns of alcohol drinking and its association with obesity: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994". BMC Public Health. 5: 126. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-5-126. PMC 1318457. PMID 16329757.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2000). "Health risks and benefits of alcohol consumption" (PDF). Alcohol Res Health. 24 (1): 5–11. PMID 11199274.

- ^ Bode C, Bode JC (1997). "Alcohol's role in gastrointestinal tract disorders" (PDF). Alcohol Health Res World. 21 (1): 76–83. PMID 15706765.

- ^ Freiberg MS, Cabral HJ, Heeren TC, Vasan RS, Curtis Ellison R (2004). "Alcohol consumption and the prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in the US.: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". Diabetes Care. 27 (12): 2954–9. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.12.2954. PMID 15562213.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yoon YS, Oh SW, Baik HW, Park HS, Kim WY (1 July 2004). "Alcohol consumption and the metabolic syndrome in Korean adults: the 1998 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". Am J Clin Nutr. 80 (1): 217–24. PMID 15213051.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ La Vecchia C, Decarli A, Ferraroni M, Negri E (1994). "Alcohol drinking and prevalence of self-reported gallstone disease in the 1983 Italian National Health Survey". Epidemiology. 5 (5): 533–6. PMID 7986868.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leitzmann MF, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ; et al. (1999). "Prospective study of alcohol consumption patterns in relation to symptomatic gallstone disease in men". Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 23 (5): 835–41. PMID 10371403.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sahi T, Paffenbarger RS, Hsieh CC, Lee IM (1 April 1998). "Body mass index, cigarette smoking, and other characteristics as predictors of self-reported, physician-diagnosed gallbladder disease in male college alumni". Am J Epidemiol. 147 (7): 644–51. PMID 9554603.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simon JA, Grady D, Snabes MC, Fong J, Hunninghake DB (1998). "Ascorbic acid supplement use and the prevalence of gallbladder disease. Heart & Estrogen-Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group". J Clin Epidemiol. 51 (3): 257–65. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(97)80280-6. PMID 9495691.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barve A, Khan R, Marsano L, Ravindra KV, McClain C (2008). "Treatment of alcoholic liver disease". Ann Hepatol. 7 (1): 5–15. PMID 18376362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fehér J, Lengyel G (2008). "[Silymarin in the treatment of chronic liver diseases: past and future]". Orv Hetil (in Hungarian). 149 (51): 2413–8. doi:10.1556/OH.2008.28519. PMID 19073452.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Voigt MD (2005). "Alcohol in hepatocellular cancer". Clin Liver Dis. 9 (1): 151–69. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2004.10.003. PMID 15763234.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Morgan TR, Mandayam S, Jamal MM (2004). "Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma". Gastroenterology. 127 (5 Suppl 1): S87–96. PMID 15508108.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM (2008). "Acute pancreatitis". Lancet. 371 (9607): 143–52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60107-5. PMID 18191686.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bachmann K, Mann O, Izbicki JR, Strate T (2008). "Chronic pancreatitis--a surgeons' view". Med. Sci. Monit. 14 (11): RA198–205. PMID 18971885.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nair RJ, Lawler L, Miller MR (2007). "Chronic pancreatitis". Am Fam Physician. 76 (11): 1679–88. PMID 18092710.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tattersall SJ, Apte MV, Wilson JS (2008). "A fire inside: current concepts in chronic pancreatitis". Intern Med J. 38 (7): 592–8. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01715.x. PMID 18715303.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hirvonen T, Pietinen P, Virtanen M, Albanes D, Virtamo J (15 July 1999). "Nutrient intake and use of beverages and the risk of kidney stones among male smokers". Am J Epidemiol. 150 (2): 187–94. PMID 10412964.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Soucie JM, Coates RJ, McClellan W, Austin H, Thun M (1 March 1996). "Relation between geographic variability in kidney stones prevalence and risk factors for stones". Am J Epidemiol. 143 (5): 487–95. PMID 8610664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Stampfer MJ (1 February 1996). "Prospective study of beverage use and the risk of kidney stones". Am J Epidemiol. 143 (3): 240–7. PMID 8561157.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Curhan GC, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ (1 April 1998). "Beverage use and risk for kidney stones in women". Ann Intern Med. 128 (7): 534–40. PMID 9518397.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taniguchi N, Kaneko S (1997). "[Alcoholic effect on male sexual function]". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 55 (11): 3040–4. PMID 9396310.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Alcohol consumption and male breasts

- ^ Alcohol, estrogen levels, breast size & cancer risk

- ^ Carlsson S, Hammar N, Grill V, Kaprio J (2003). "Alcohol consumption and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a 20-year follow-up of the Finnish twin cohort study". Diabetes Care. 26 (10): 2785–90. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.10.2785. PMID 14514580.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J Hong1, R R Smith, A E Harvey and N P Núñez Alcohol consumption promotes insulin sensitivity without affecting body fat levels International Journal of Obesity (2009) 33, 197–203; doi:10.1038/ijo.2008.266

- ^ Star VL, Hochberg MC (1993). "Prevention and management of gout". Drugs. 45 (2): 212–22. PMID 7681372.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Eggebeen AT (2007). "Gout: an update". Am Fam Physician. 76 (6): 801–8. PMID 17910294.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://arc.org.uk/arthinfo/patpubs/6033/6033.asp

- ^ Myllykangas-Luosujärvi R, Aho K, Kautiainen H, Hakala M (2000). "Reduced incidence of alcohol related deaths in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis". Ann Rheum Dis. 59 (1): 75–6. doi:10.1136/ard.59.1.75. PMC 1752983. PMID 10627433.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nagata C, Fujita S, Iwata H; et al. (1995). "Systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control epidemiologic study in Japan". Int J Dermatol. 34 (5): 333–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb03614.x. PMID 7607794.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aho K, Heliövaara M (1993). "Alcohol, androgens and arthritis". Ann Rheum Dis. 52 (12): 897. doi:10.1136/ard.52.12.897-b. PMC 1005228. PMID 8311545.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hardy CJ, Palmer BP, Muir KR, Sutton AJ, Powell RJ (1998). "Smoking history, alcohol consumption, and systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study". Ann Rheum Dis. 57 (8): 451–5. doi:10.1136/ard.57.8.451. PMC 1752721. PMID 9797548.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Källberg H, Jacobsen S, Bengtsson C; et al. (2008). "Alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of rheumatoid arthritis; Results from two Scandinavian case-control studies". Ann Rheum Dis. 68: 222. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.086314. PMID 18535114.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jonsson IM, Verdrengh M, Brisslert M; et al. (2007). "Ethanol prevents development of destructive arthritis". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104 (1): 258–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608620104. PMC 1765445. PMID 17185416.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Myllykangas-Luosujärvi R, Aho K, Kautiainen H, Hakala M (2000). "Reduced incidence of alcohol related deaths in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis". Ann Rheum Dis. 59 (1): 75–6. doi:10.1136/ard.59.1.75. PMC 1752983. PMID 10627433.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Voigt LF, Koepsell TD, Nelson JL, Dugowson CE, Daling JR (1994). "Smoking, obesity, alcohol consumption, and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis". Epidemiology. 5 (5): 525–32. PMID 7986867.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Siris ES, Miller PD, Barrett-Connor E; et al. (2001). "Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment". JAMA. 286 (22): 2815–22. doi:10.1001/jama.286.22.2815. PMID 11735756.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rapuri PB, Gallagher JC, Balhorn KE, Ryschon KL (1 November 2000). "Alcohol intake and bone metabolism in elderly women". Am J Clin Nutr. 72 (5): 1206–13. PMID 11063451.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holbrook TL, Barrett-Connor E (1993). "A prospective study of alcohol consumption and bone mineral density". BMJ. 306 (6891): 1506–9. PMC 1677960. PMID 8518677.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kostović K, Lipozencić J (2004). "Skin diseases in alcoholics". Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 12 (3): 181–90. PMID 15369644.

- ^ Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Bode G, Adler G (6 December 1997). "Relation of smoking and alcohol and coffee consumption to active Helicobacter pylori infection: cross sectional study". BMJ. 315 (7121): 1489–92. PMC 2127930. PMID 9420488.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Willett WC (1997). "A prospective study of alcohol, smoking, caffeine, and the risk of duodenal ulcer in men". Epidemiology. 8 (4): 420–4. doi:10.1097/00001648-199707000-00012. PMID 9209857.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cohen S, Tyrrell DA, Russell MA, Jarvis MJ, Smith AP (1993). "Smoking, alcohol consumption, and susceptibility to the common cold". Am J Public Health. 83 (9): 1277–83. doi:10.2105/AJPH.83.9.1277. PMC 1694990. PMID 8363004.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takkouche B, Regueira-Méndez C, García-Closas R, Figueiras A, Gestal-Otero JJ, Hernán MA (2002). "Intake of wine, beer, and spirits and the risk of clinical common cold". Am J Epidemiol. 155 (9): 853–8. doi:10.1093/aje/155.9.853. PMID 11978590.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Volume 44 Alcohol Drinking: Summary of Data Reported and Evaluation

- ^ National Toxicology Program Alcoholic Beverage Consumption: Known to be a human carcinogen First listed in the Ninth Report on Carcinogens (2000)(PDF)

- ^ Burden of alcohol-related cancer substantial

- ^ WCRF Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective

- ^ New Scientist article "Alcohol's link to cancer explained"

- ^ Ulleland CN (1972). "The offspring of alcoholic mothers". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 197: 167–9. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1972.tb28142.x. PMID 4504588.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Abel EL, Sokol RJ (1987). "Incidence of foetal alcohol syndrome and economic impact of FAS-related anomalies". Drug Alcohol Depend. 19 (1): 51–70. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(87)90087-1. PMID 3545731.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)