2009 swine flu pandemic: Difference between revisions

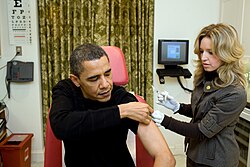

m Replacing A_nurse_vaccines_Barack_Obama_against_H1N1.jpg with File:A_nurse_vaccinates_Barack_Obama_against_H1N1.jpg (by NuclearWarfare because: Image renamed). |

|||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

The [[basic reproduction number]] (the average number of other individuals that each infected individual will infect, in a population that has no immunity to the disease) for the 2009 novel H1N1 is estimated to be 1.75.<ref>{{cite journal|first1=Duygu |last1=Balcan |first2=Hao |last2=Hu |first3=Bruno |last3=Goncalves |first4=Paolo |last4=Bajardi |first5=Chiara |last5=Poletto |first6=Jose J.|last6=Ramasco|first7=Daniela|last7=Paolotti|first8=Nicola|last8=Perra |first9=Michele |last9=Tizzoni |date=2009-09-14|title=Seasonal transmission potential and activity peaks of the new influenza A(H1N1): a Monte Carlo likelihood analysis based on human mobility|journal=BMC Medicine |volume=7 |issue=45 |pages=29 |accessdate=2009-10-25 |doi=10.1186/1741-7015-7-45 |id={{arXiv|0909.2417v1}}}}</ref> A December 2009 study found that the transmissibility of the H1N1 influenza virus in households is lower than that seen in past pandemics. Most transmissions occur soon before or after the onset of symptoms.<ref>The New England Journal of Medicine http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/361/27/2619</ref> |

The [[basic reproduction number]] (the average number of other individuals that each infected individual will infect, in a population that has no immunity to the disease) for the 2009 novel H1N1 is estimated to be 1.75.<ref>{{cite journal|first1=Duygu |last1=Balcan |first2=Hao |last2=Hu |first3=Bruno |last3=Goncalves |first4=Paolo |last4=Bajardi |first5=Chiara |last5=Poletto |first6=Jose J.|last6=Ramasco|first7=Daniela|last7=Paolotti|first8=Nicola|last8=Perra |first9=Michele |last9=Tizzoni |date=2009-09-14|title=Seasonal transmission potential and activity peaks of the new influenza A(H1N1): a Monte Carlo likelihood analysis based on human mobility|journal=BMC Medicine |volume=7 |issue=45 |pages=29 |accessdate=2009-10-25 |doi=10.1186/1741-7015-7-45 |id={{arXiv|0909.2417v1}}}}</ref> A December 2009 study found that the transmissibility of the H1N1 influenza virus in households is lower than that seen in past pandemics. Most transmissions occur soon before or after the onset of symptoms.<ref>The New England Journal of Medicine http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/361/27/2619</ref> |

||

The H1N1 virus has been transmitted to animals, including [[swine]], [[turkey]]s, [[ferret]]s, household [[cat]]s, at least one [[dog]], and a [[cheetah]].<ref> |

The H1N1 virus has been transmitted to animals, including [[swine]], [[turkey (bird)|turkey]]s, [[ferret]]s, household [[cat]]s, at least one [[dog]], and a [[cheetah]].<ref> |

||

{{cite news |

{{cite news |

||

| url=http://consults.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/11/05/can-pets-get-swine-flu/ |

| url=http://consults.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/11/05/can-pets-get-swine-flu/ |

||

Revision as of 08:08, 20 February 2010

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (January 2010) |

| 2009 swine flu pandemic |

|---|

Template:2009 flu pandemic data

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

The 2009 flu pandemic is a global outbreak of a new strain of H1N1 influenza virus, often referred to colloquially as "swine flu".[2] Although the virus, first detected in April 2009, contains a combination of genes from swine, avian (bird), and human influenza viruses, it cannot be spread by eating pork or pork products.[3][4]

The outbreak began in the state of Veracruz, Mexico, with evidence that there had been an ongoing epidemic for months before it was officially recognized as such.[5] The Mexican government closed most of Mexico City's public and private facilities in an attempt to contain the spread of the virus. However the virus continued to spread globally, clinics in some areas were overwhelmed by people infected, and the World Health Organization (WHO) and US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) stopped counting cases and in June declared the outbreak to be a pandemic.[6]

While only mild symptoms are experienced by the majority of people,[6] some have more severe symptoms. Mild symptoms may include fever, sore throat, cough, headache, muscle or joint pains, and nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Those at risk of a more severe infection include: asthmatics, diabetics,[7] those with obesity, heart disease, the immunocompromised, children with neurodevelopmental conditions,[8] and pregnant women.[9] In addition, even for persons previously very healthy, a small percentage of patients will develop viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome. This manifests itself as increased breathing difficulty and typically occurs 3–6 days after initial onset of flu symptoms.[10][11]

Similar to other influenza viruses, pandemic H1N1 is typically contracted by person to person transmission through respiratory droplets.[12] Symptoms usually last 4–6 days.[13] To avoid spreading the infection, it is recommended that those with symptoms stay home, away from school, work, and crowded places. Those with more severe symptoms or those in an at risk group may benefit from antivirals (oseltamivir or zanamivir).[14] Currently, there are Template:Swine-flu-deaths confirmed deaths worldwide. This figure is a sum of confirmed deaths reported by national authorities and the WHO states that total mortality (including deaths unconfirmed or unreported) from the new H1N1 strain is "unquestionably higher" than this.[15] The CDC estimates that, in the United States alone, and as of November 14, there had been 9,820 deaths (range 7,070–13,930) caused by swine flu.[16] On January 18, 2010, Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General, said the pandemic appeared to be easing in the northern hemisphere but could still cause infections until winter ends in April, and that it was too soon to say what would happen once the southern hemisphere enters winter and the virus becomes more infectious.[17]

Classification

The initial outbreak was called the "H1N1 influenza", or "Swine Flu" by American media. It is called pandemic H1N1/09 virus by the WHO,[18] while the CDC refers to it as "novel influenza A (H1N1)" or "2009 H1N1 flu".[19] In the Netherlands, it was originally called "Pig Flu", but is now called "New Influenza A (H1N1)" by the national health institute, although the media and general population use the name "Mexican Flu". South Korea and Israel briefly considered calling it the "Mexican virus".[20] Later, the South Korean press used "SI", short for "swine influenza". Taiwan suggested the names "H1N1 flu" or "new flu", which most local media adopted.[21] The World Organization for Animal Health proposed the name "North American influenza".[22] The European Commission adopted the term "novel flu virus".[23]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of swine flu are similar to other influenzas, and may include a fever, cough (typically a "dry cough"), headache, muscle or joint pain, sore throat, chills, fatigue, and runny nose. Diarrhea, vomiting, and neurological problems have also been reported in some cases.[24][25] People at higher risk of serious complications include those aged over 65, children younger than 5, children with neurodevelopmental conditions, pregnant women (especially during the third trimester),[10][26] and those of any age with underlying medical conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, or a weakened immune system (e.g., taking immunosuppressive medications or infected with HIV).[9] More than 70% of hospitalizations in the US have been people with such underlying conditions, according to the CDC.[27]

In September 2009 the CDC reported that the H1N1 flu "seems to be taking a heavier toll among chronically ill children than the seasonal flu usually does."[28] Of the children who had died so far, nearly two-thirds had pre-existing nervous system disorders, such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or developmental delays. "Children with nerve and muscle problems may be at especially high risk for complications".[28]

Symptoms in severe cases

The World Health Organization reports that the clinical picture in severe cases is strikingly different from the disease pattern seen during epidemics of seasonal influenza. While people with certain underlying medical conditions are known to be at increased risk, many severe cases occur in previously healthy people. In these patients, predisposing factors that increase the risk of severe illness are not presently understood, though research is under way. In severe cases, patients generally begin to deteriorate around 3 to 5 days after symptom onset. Deterioration is rapid, with many patients progressing to respiratory failure within 24 hours, requiring immediate admission to an intensive care unit. Upon admission, most patients need immediate respiratory support with mechanical ventilation.[29]

A November 2009 CDC recommendation stated that the following constitute "emergency warning signs" and advised seeking immediate care if a person experiences any one of these signs:[30]

|

|

Other complications

Fulminant myocarditis has been linked to infection with H1N1 infection, with at least 4 cases of myocarditis confirmed in patients also infected with A/H1N1. 3 out of the 4 cases of H1N1 asscoiated myocarditis were classified as fulminant, and one of the patients died. [31] Also, there appears to be a link between severe A/H1N1 influenza infection and pulmonary embolism. In one report, 5 out of 14 patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe A/H1N1 infection were found to have pulmonary emboli.[32]

Diagnosis

Confirmed diagnosis of pandemic H1N1/09 flu requires testing of a nasopharyngeal, nasal, or oropharyngeal tissue swab from the patient.[33] Real-time RT-PCR is the recommended test as others are unable to differentiate between pandemic H1N1/09 and regular seasonal flu.[33] However, most people with flu symptoms do not need a test for pandemic H1N1/09 flu specifically, because the test results usually do not affect the recommended course of treatment.[34] The CDC recommends testing only for people who are hospitalized with suspected flu, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems.[34] For the mere diagnosis of influenza and not pandemic H1N1/09 flu specifically, more widely available tests include rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDT), which yield results in about 30 minutes, and direct and indirect immunofluorescence assays (DFA and IFA), which take 2–4 hours.[35] Due to the high rate of RIDT false negatives, the CDC advises that patients with illnesses compatible with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection but with negative RIDT results should be treated empirically based on the level of clinical suspicion, underlying medical conditions, severity of illness, and risk for complications, and if a more definitive determination of infection with influenza virus is required, testing with rRT-PCR or virus isolation should be performed.[36] Dr. Rhonda Medows of the Georgia Department of Community Health states that the rapid tests are incorrect anywhere from 30-90% of the time. She warns doctors in her state not to use rapid flu tests because they're wrong so often.[37] The use of RIDTs has also been questioned by researcher Paul Schreckenberger of the Loyola University Health System, who suggests that rapid tests may actually pose a dangerous public health risk.[38] Dr. Nikki Shindo of the WHO has expressed regret at reports of treatment being delayed by waiting for H1N1 test results and suggests that "doctors should not wait for the laboratory confirmation but make diagnosis based on clinical and epidemiological backgrounds and start treatment early."[39]

Virus characteristics

The virus is a novel strain of influenza for which extant vaccines against seasonal flu provide little protection. A study at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published in May 2009, found that children had no preexisting immunity to the new strain but that adults, particularly those over 60, had some degree of immunity. Children showed no cross-reactive antibody reaction to the new strain, adults aged 18 to 64 had 6–9%, and older adults 33%.[40][41] While it has been thought that these findings suggest the partial immunity in older adults may be due to previous exposure to similar seasonal influenza viruses, a November 2009 study of a rural unvaccinated population in China found only a 0.3% cross-reactive antibody reaction to the H1N1 strain, suggesting that previous vaccinations for seasonal flu and not exposure may have resulted in the immunity found in the older US population.[42]

It has been determined that the strain contains genes from five different flu viruses: North American swine influenza, North American avian influenza, human influenza, and two swine influenza viruses typically found in Asia and Europe. Further analysis has shown that several proteins of the virus are most similar to strains that cause mild symptoms in humans, leading virologist Wendy Barclay to suggest on May 1, 2009 that the initial indications are that the virus was unlikely to cause severe symptoms for most people.[43]

The virus is currently less lethal than previous pandemic strains and kills about 0.01-0.03% of those infected; the 1918 influenza was about one hundred times more lethal and had a case fatality rate of 2-3%.[44] By November 14, the virus had infected 1 in 6 Americans with 200,000 hospitalizations and 10,000 deaths - as many hospitalizations and fewer deaths than in an average flu season overall, but with much higher risk for those under 50. With deaths of 1,100 children and 7,500 adults 18 to 64, these figures "are much higher than in a usual flu season".[45]

Transmission

Spread of the H1N1 virus is thought to occur in the same way that seasonal flu spreads. Flu viruses are spread mainly from person to person through coughing or sneezing by people with influenza. Sometimes people may become infected by touching something – such as a surface or object – with flu viruses on it and then touching their mouth or nose.[3] The basic reproduction number (the average number of other individuals that each infected individual will infect, in a population that has no immunity to the disease) for the 2009 novel H1N1 is estimated to be 1.75.[46] A December 2009 study found that the transmissibility of the H1N1 influenza virus in households is lower than that seen in past pandemics. Most transmissions occur soon before or after the onset of symptoms.[47]

The H1N1 virus has been transmitted to animals, including swine, turkeys, ferrets, household cats, at least one dog, and a cheetah.[48][49][50][51]

Prevention

The CDC recommended that initial vaccine doses should go to priority groups such as pregnant women, people who live with or care for babies under six months old, children six months to four years old and health-care workers.[52] In the UK, the NHS recommended vaccine priority go to people over six months old who were clinically at risk for seasonal flu, pregnant women, and households of people with compromised immunity.[53]

Although it was initially thought that two injections would be required, clinical trials showed that the new vaccine protects adults "with only one dose instead of two", and so the limited vaccine supplies would go twice as far as had been predicted.[54][55] Costs would also be lowered by having a "more efficient vaccine".[54] For children under the age of 10, two administrations of the vaccine, spaced 21 days apart, are recommended.[56][57] The seasonal flu will still require a separate vaccination.[58]

Health officials worldwide were also concerned because the virus was new and could easily mutate and become more virulent, even though most flu symptoms were mild and lasted only a few days without treatment. Officials also urged communities, businesses and individuals to make contingency plans for possible school closures, multiple employee absences for illness, surges of patients in hospitals and other effects of potentially widespread outbreaks.[59]

Public health response

On April 27, 2009, the European Union health commissioner advised Europeans to postpone nonessential travel to the United States or Mexico. This followed the discovery of the first confirmed case in Spain.[60] On May 6, 2009, the Public Health Agency of Canada announced that their National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) had mapped the genetic code of the swine flu virus, the first time that had been done.[61] In England, the National Health Service launched a website, the National Pandemic Flu Service,[62] allowing patients to self-assess and get an authorization number for antiviral medication. The system was expected to reduce the burden on general practitioners.[53]

US officials observed that six years of concern about H5N1 avian flu did much to prepare for the current swine flu outbreak, noting that after H5N1 emerged in Asia, ultimately killing about 60% of the few hundred people infected by it over the years, many countries took steps to try to prevent any similar crisis from spreading further.[63] The CDC and other American governmental agencies[64] used the summer lull to take stock of the United States's response to swine flu and attempt to patch any gaps in the public health safety net before flu season started in early autumn.[65] Preparations included planning a second influenza vaccination program in addition to the one for seasonal influenza, and improving coordination between federal, state, and local governments and private health providers.[65] On October 24, 2009, U.S. President Obama declared swine flu a national emergency, giving Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius authority to grant waivers to requesting hospitals from usual federal requirements.[66]

Vaccines

As of November 19, 2009[update], over 65 million doses of vaccine had been administered in over 16 countries; the vaccine seems safe and effective, producing a strong immune response that should protect against infection.[67] The current trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine neither increases nor decreases the risk of infection with H1N1, since the new pandemic strain is quite different from the strains used in this vaccine.[68][69] Overall the safety profile of the new H1N1 vaccine is similar to that of the seasonal flu vaccine, and as of November 2009 fewer than a dozen cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome had been reported post-vaccination.[70] Only a few of these are suspected to be actually related to the H1N1 vaccination, and only temporary illness has been observed.[70] This is in strong contrast to the 1976 swine flu outbreak, where mass vaccinations in the United States caused over 500 cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome and led to 25 deaths.[71]

There are safety concerns for people who are allergic to eggs because the viruses for the vaccine are grown in chicken-egg-based cultures. People with egg allergies may be able to receive the vaccine, after consultation with their physician, in graded doses in a careful and controlled environment.[72] A vaccine manufactured by Baxter is made without using eggs, but requires two doses three weeks apart to produce immunity.[73]

As of late November, in Canada there had been 24 confirmed cases of anaphylactic shock following vaccination, including one death. The estimated rate is 1 anaphylactic reaction per 312,000 persons receiving the vaccine, however there had been one batch of vaccine in which 6 persons suffered anaphylaxis out of 157,000 doses given. Dr. David Butler-Jones, Canada’s chief public health officer, stated that even though this was an adjuvanted vaccine, that did not appear to be the cause of this severe allergic reaction in these 6 patients.[74][75]

In January 2010, Wolfgang Wodarg, a Social Democrat deputy who trained as a doctor and now chairs the health committee at the Council of Europe, claimed major firms organised a "campaign of panic" to put pressure on the World Health Organisation (WHO) to declare a "false pandemic" to sell vaccines. Dr Wodarg said the WHO’s “false pandemic” flu campaign is “one of the greatest medicine scandals of the century.” He said that the “false pandemic” campaign began last May in Mexico City, when a hundred or so “normal” reported influenza cases were declared to be the beginning of a threatening new pandemic, although he said there was little scientific evidence for this. Nevertheless he argued that the WHO, “in cooperation with some big pharmaceutical companies and their scientists, re-defined pandemics,” removing the statement that “an enormous amount of people have contracted the illness or died” from its existing definition and replacing it by stating simply that there has to be a virus, spreading beyond borders and to which people have no immunity.[76] The WHO has responded by stating that it took its duty to provide independent advice seriously and guarded against interference from outside interests. Announcing a review of its actions, WHO spokeswoman Fadela Chaib stated that, "Criticism is part of an outbreak cycle. We expect and indeed welcome criticism and the chance to discuss it."[77][78]

Infection control

Travel precautions

On May 7, 2009 the WHO stated that containment was not feasible and that countries should focus on mitigating the effect of the virus. It did not recommend closing borders or restricting travel.[79] On April 26, 2009, the Chinese government announced that visitors returning from flu-affected areas who experienced flu-like symptoms within two weeks would be quarantined.[80]

US airlines made no major changes as of the beginning of June 2009, but continued standing practices that included looking for passengers with symptoms of flu, measles, or other infections, and relying on in-flight air filters to ensure that aircraft were sanitized.[81] Masks were not generally provided by airlines and the CDC did not recommend that airline crews wear them.[81] Some non-US airlines, mostly Asian ones, including Singapore Airlines, China Eastern Airlines, China Southern Airlines, Cathay Pacific, and Mexicana Airlines, took measures such as stepping up cabin cleaning, installing state-of-the-art air filters, and allowing in-flight staff to wear face masks.[81]

Schools

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2009) |

US government officials are especially concerned about schools because the swine flu virus appears to disproportionately affect young and school-age people, between ages 6 months to 24 years of age.[82] The swine flu outbreak has led to numerous precautionary school closures in several countries. Rather than closing schools, the CDC recommended in August that students and school workers with flu symptoms should stay home for either seven days total, or until 24 hours after symptoms subside—whichever is longer.[83] The CDC also recommended that colleges should consider suspending fall 2009 classes if the virus begins to cause severe illness in a significantly larger share of students than last spring. They have additionally urged schools to suspend any rules, including penalizing late papers or missed classes, or requiring a doctor's note, to enforce "self-isolation" and prevent students from venturing out while ill;[84] schools were advised to set aside a room for people developing flu-like symptoms while they wait to go home and that surgical masks be used for ill students or staff and those caring for them.[85]

In California, school districts and universities are on alert and working with health officials to launch education campaigns. Many planned to stockpile medical supplies and discuss worst-case scenarios, including plans to provide lessons and meals for low-income children in case elementary and secondary schools close.[86] University of California campuses were stockpiling supplies, from paper masks and hand sanitizer to food and water.[86] To help prepare for contingencies, University of Maryland School of Medicine professor of pediatrics James C. King Jr. suggests that every county should create an "influenza action team" to be run by the local health department, parents, and school administrators.[87] As of 28 October 2009[update], about 600 Schools in the United States have been temporarily closed, affecting over 126,000 students in 19 states.[88]

Workplace

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2009) |

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with input from the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), have developed updated guidance[89] and a video for employers to use as they develop or review and update plans to respond to swine flu now and during the upcoming fall and winter influenza season. The guidance states that employers should consider and communicate their objectives, which may include reducing transmission among staff, protecting people who are at increased risk of influenza related complications from getting infected with influenza, maintaining business operations, and minimizing adverse effects on other entities in their supply chains.[89]

The CDC estimates that as much as 40% of the workforce, in a worst-case scenario, might be unable to work at the peak of the pandemic due to the need for many healthy adults to stay home and care for an ill family member,[90] and advising that individuals should have steps in place should a workplace close down or a situation arise that requires working from home.[91] The CDC further advises that persons in the workplace should stay home sick for seven days after getting the flu, or 24 hours after symptoms end, whichever is longer.[83] In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has also issued general guidance for employers.[92]

Facial masks

The CDC does not recommend use of face masks or respirators in non-health care settings, such as schools, workplaces, or public places, with a few exceptions: people who are ill with the virus should consider wearing one when around other people, and people who are at risk for severe illness while caring for someone with the flu.[93] There is some disagreement about the value of wearing either facial masks, some experts fearing that masks may give people a false sense of security and should not replace other standard precautions.[94] Masks may benefit people in close contact with infected persons but it was unknown whether they prevent swine flu infection.[94] Yukihiro Nishiyama, professor of virology at Nagoya University's School of Medicine, commented that the masks are "better than nothing, but it's hard to completely block out an airborne virus since it can easily slip through the gaps".[95] According to mask manufacturer 3M, masks will filter out particles in industrial settings, but "there are no established exposure limits for biological agents such as swine flu virus."[94] However, despite the lack of evidence of effectiveness, the use of such masks is common in Asia.[95][96] Masks are particularly popular in Japan, where cleanliness and hygiene are highly valued and where etiquette obligates those who are sick to wear masks to avoid their spreading disease.[95]

Quarantine

Countries have initiated quarantines or have threatened to quarantine foreign visitors suspected of having or being in contact with others who may have been infected. In May, the Chinese government confined 21 US students and three teachers to their hotel rooms.[97] As a result, the US State Department issued a travel alert about China's anti-flu measures and warned travelers about traveling to China if ill.[98] In Hong Kong, an entire hotel was quarantined with 240 guests;[99] Australia ordered a cruise ship with 2,000 passengers to stay at sea because of a swine flu threat.[100] Egyptian Muslims who went on the annual pilgrimage to Mecca risked being quarantined upon their return.[101] Russia and Taiwan said they would quarantine visitors with fevers who come from areas where the flu is present.[102] Japan quarantined 47 airline passengers in a hotel for a week in mid-May,[103] then in mid-June India suggested pre-screening "outbound" passengers from countries thought to have a high rate of infection.[104]

Pigs and food safety

The pandemic virus is a type of swine influenza, derived originally from a strain that lived in pigs and this origin gave rise to the common name of "swine flu". This term is widely used by mass media. The virus has been found in American[105] and Canadian[106] hogs, as well as in hogs in Northern Ireland, Argentina, and Norway.[107] However, despite its origin in pigs, this strain is transmitted between people and not from swine to people.[5] Leading health agencies and the United States Secretary of Agriculture have stressed that eating properly cooked pork or other food products derived from pigs would not cause flu.[108][109] Nevertheless, on April 27, Azerbaijan imposed a ban on the importation of animal husbandry products from America.[110] The Indonesian government also halted the importation of pigs and initiated the examination of 9 million pigs in Indonesia.[111] The Egyptian government ordered the slaughter of all pigs in Egypt on April 29, 2009.[112]

Treatment

A number of methods have been recommended to help ease symptoms, including adequate liquid intake and rest.[113] Over-the-counters pain medications such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen do not kill the virus, however they may be useful to reduce symptoms.[114] Aspirin and other salicylate products should not be used (by anyone, but especially by people under 19) with any flu-type symptoms because of the risk of developing Reye's Syndrome.[115]

If the fever is mild and there are no other complications, fever medication is not recommended.[114] Most people recover without medical attention, although those with pre-existing or underlying medical conditions are more prone to complications and may benefit from further treatments.[30]

People in at-risk groups should be treated with antivirals (oseltamivir or zanamivir) as soon as possible when they first experience flu symptoms. The at risk groups includes pregnant and post partum women, children under 2 years old, and people with underlying conditions such as respiratory problems.[14] People who are not from the at-risk group who have persistent or rapidly worsening symptoms should also be treated with antivirals. These symptoms include difficulty breathing and a high fever that lasts beyond 3 days. People who have developed pneumonia should be given both antivirals and antibiotics, as in many severe cases of H1N1-caused illness, bacterial infection develops.[39] Antivirals are most useful if given within 48 hours of the start of symptoms and may improve outcomes in hospitalized patients.[116] In those beyond 48 hours who are moderately or severely ill antiviral may still be beneficial.[12] If oseltamivir (Tamiflu) is unavailable or cannot be used zanamivir (Relenza) is recommended as a substitute.[14][117] Peramivir is an experimental antiviral drug approved for hospitalized patients in cases where the other available methods of treatment are ineffective or unavailable.[118]

To help avoid shortages of these drugs, the CDC recommended oseltamivir treatment primarily for people hospitalized with pandemic flu; people at risk of serious flu complications due to underlying medical conditions; and patients at risk of serious flu complications. The CDC warned that the indiscriminate use of antiviral medications to prevent and treat influenza could ease the way for drug-resistant strains to emerge which would make the fight against the pandemic that much harder. In addition, a British report found that people often failed to complete a full course of the drug or took the medication when not needed.[119]

Side effects

Both medications have known side effects, including lightheadedness, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and trouble breathing. Children were reported to be at increased risk of self-injury and confusion after taking oseltamivir.[113] The WHO warns against buying antiviral medications from online sources, and estimates that half the drugs sold by online pharmacies without a physical address are counterfeit.[120]

Resistance

As of February 2010[update], the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 225 out of over 15,000 samples of the prevalent 2009 pandemic H1N1 (swine) flu tested worldwide have shown resistance to oseltamivir (Tamiflu).[121] This is not totally unexpected as 99.6% of the seasonal H1N1 flu strains tested have developed resistance to oseltamivir.[122] No circulating flu has yet shown any resistance to zanamivir (Relenza), the other available anti-viral.[12]

Effectiveness of antivirals questioned

On December 8, 2009, the Cochrane Collaboration, which reviews medical evidence, announced in a review published in the British Medical Journal that it had reversed its previous findings that the antiviral drugs oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) can ward off pneumonia and other serious conditions linked to influenza. They reported that an analysis of 20 studies showed oseltamivir offered mild benefits for healthy adults if taken within 24 hours of onset of symptoms, but found no clear evidence it prevented lower respiratory tract infections or other complications of influenza.[123][124] Their published finding relates only to its use in healthy adults with influenza; they say nothing about its use in patients judged to be at high risk of complications (pregnant women, children under 5, and those with underlying medical conditions), and uncertainty over its role in reducing complications in healthy adults may still leave it as a useful drug for reducing the duration of symptoms. The drugs might eventually be demonstrated to be effective against flu-related complications; in general, the Cochrane Collaboration concluded "Paucity of good data."[124][125]

Some specific results from the British Medical Journal article include, "The efficacy of oral oseltamivir against symptomatic laboratory confirmed influenza was 61% (risk ratio 0.39, 95% confidence interval 0.18 to 0.85) at 75 mg daily [...] The remaining evidence suggests oseltamivir did not reduce influenza related lower respiratory tract complications (risk ratio 0.55, 95% confidence interval 0.22 to 1.35)."[124] Notice especially the wide range for this second result.

Epidemiology

While it is not known precisely where or when the virus originated,[126][127] analyses in scientific journals have suggested that the H1N1 strain responsible for the current outbreak first evolved in September 2008 and circulated amongst humans for several months before being formally recognized and identified as a novel strain of influenza.[126][128]

Mexico

The virus was first reported in two US children in March 2009, but health officials have reported that it apparently infected people as early as January 2009 in Mexico.[129] The outbreak was first detected in Mexico City on March 18, 2009;[130] immediately after the outbreak was officially announced, Mexico notified the US and world health orginization, and within days of the outbreak Mexico City was "effectively shut down".[131] Some countries canceled flights to Mexico while others halted trade. Calls to close the border to contain the spread were rejected.[131] Mexico already had hundreds of non lethal cases before the outbreak was officially discovered, and was therefore in the midst of a "silent epidemic". As a result, Mexico was reporting only the most serious cases that showed some of the more severe signs different than those of normal flu, possibly leading to a skewed initial estimate of the case fatality rate.[130]

United States

The new strain was first identified by the CDC in two children, neither of whom had been in contact with pigs. The first case, from San Diego County, California, was confirmed from clinical specimens (nasopharyngeal swab) examined by the CDC on April 14, 2009. A second case, from nearby Imperial County, California, was confirmed on April 17. The patient in the first confirmed case had flu symptoms including fever and cough on clinical exam on March 30, and the second on March 28.[132]

The first confirmed swine flu death occurred at Texas Children's Hospital in Houston, Texas.[133]

Data reporting and accuracy

Influenza surveillance information "answers the questions of where, when, and what influenza viruses are circulating. It can be used to determine if influenza activity is increasing or decreasing, but cannot be used to ascertain how many people have become ill with influenza".[134] For example, as of late June 2009 influenza surveillance information showed the US had nearly 28,000 laboratory-confirmed cases including 3,065 hospitalizations and 127 deaths; but mathematical modeling showed an estimated 1 million Americans currently had the 2009 pandemic flu according to Lyn Finelli, a flu surveillance official with the CDC.[135] Estimating deaths from influenza is also a complicated process. In 2005, influenza only appeared on the death certificates of 1,812 people in the US. The average annual US death toll from flu is, however, estimated to be 36,000.[136] The CDC explains[137] that "...influenza is infrequently listed on death certificates of people who die from flu-related complications." and furthermore that "Only counting deaths where influenza was included on a death certificate would be a gross underestimation of influenza's true impact."

With respect to the current swine flu pandemic, influenza surveillance information is available but almost no studies have attempted to estimate the total number of deaths attributable to swine flu. Two studies have been performed by the CDC, however; the most recent estimates that there were 9,820 deaths (range 7,070-13,930) attributable to swine flu from April to November the 14th.[16] During the same period, 1642 deaths were officially confirmed as caused by swine flu.[138][139] The WHO states that total mortality (including deaths unconfirmed or unreported) from swine flu is "unquestionably higher" than its own confirmed death statistics.[15]

The initial outbreak received a week of near-constant media attention. Epidemiologists cautioned that the number of cases reported in the early days of an outbreak can be very inaccurate and deceptive due to several causes, among them selection bias, media bias, and incorrect reporting by governments. Inaccuracies could also be caused by authorities in different countries looking at differing population groups. Furthermore, countries with poor health care systems and older laboratory facilities may take longer to identify or report cases.[140] "...[E]ven in developed countries the [numbers of flu deaths] are uncertain, because medical authorities don't usually verify who actually died of influenza and who died of a flu-like illness."[141] Dr. Joseph S. Bresee (the CDC flu division's epidemiology chief) and Dr. Michael T. Osterholm (director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research) have pointed out that millions of people have had swine flu, usually in a mild form, so the numbers of laboratory-confirmed cases were actually meaningless, and in July 2009 the WHO stopped keeping count of individual cases and focused more on major outbreaks.[142]

History

Annual influenza epidemics are estimated to affect 5–15% of the global population. Although most cases are mild, these epidemics still cause severe illness in 3–5 million people and 250,000–500,000 deaths worldwide.[143] On average 41,400 people die each year in the United States based on data collected between 1979 and 2001.[144] In industrialized countries, severe illness and deaths occur mainly in the high-risk populations of infants, the elderly, and chronically ill patients,[143] although the swine flu outbreak (as well as the 1918 Spanish flu) differs in its tendency to affect younger, healthier people.[145]

In addition to these annual epidemics, Influenza A virus strains caused three global pandemics during the 20th century: the Spanish flu in 1918, Asian flu in 1957, and Hong Kong flu in 1968–69. These virus strains had undergone major genetic changes for which the population did not possess significant immunity.[146] Recent genetic analysis has revealed that three-quarters, or six out of the eight genetic segments of the 2009 flu pandemic strain arose from the North American swine flu strains circulating since 1998, when a new strain was first identified on a factory farm in North Carolina, and which was the first-ever reported triple-hybrid flu virus.[147]

The 1918 flu epidemic began with a wave of mild cases in the spring, followed by more deadly waves in the autumn, eventually killing hundreds of thousands in the United States.[148] The great majority of deaths in the 1918 flu pandemic were the result of secondary bacterial pneumonia. The influenza virus damaged the lining of the bronchial tubes and lungs of victims, allowing common bacteria from the nose and throat to infect their lungs. Subsequent pandemics have had many fewer fatalities due to the development of antibiotic medicines that can treat pneumonia.[149]

| 20th century flu pandemics | ||||||

| Pandemic | Year | Influenza virus type | People infected (approximate) | Estimated deaths worldwide | Case fatality rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish flu | 1918–1919 | A/H1N1[150] | 33% (500 million)[151] | 20–100 million[152][153][154] | >2.5%[155] | |

| Asian flu | 1956–1958 | A/H2N2[150] | ? | 2 million[154] | <0.1%[155] | |

| Hong Kong flu | 1968–1969 | A/H3N2[150] | ? | 1 million[154] | <0.1%[155] | |

| Seasonal flu | Every year | mainly A/H3N2, A/H1N1, and B | 5–15% (340 million – 1 billion)[156] | 250,000–500,000 per year[143] | <0.1%[157] | |

| Swine flu | 2009 | Pandemic H1N1/09 | > 622,482 (lab-confirmed)[158] | Template:Swine-flu-deaths (lab-confirmed†; ECDC)[159] ≥8,768 (lab-confirmed†; WHO)[160] |

0.03%[161] | |

- Not necessarily pandemic, but included for comparison purposes.

- ^† Note: The ratio of confirmed deaths to total deaths due to pandemic H1N1/09 flu is unknown. For more information, see "Data reporting and accuracy".

The influenza virus has also caused several pandemic threats over the past century, including the pseudo-pandemic of 1947 (thought of as mild because although globally distributed, it caused relatively few deaths),[162] the 1976 swine flu outbreak, and the 1977 Russian flu, all caused by the H1N1 subtype.[146] The world has been at an increased level of alert since the SARS epidemic in Southeast Asia (caused by the SARS coronavirus).[163] The level of preparedness was further increased and sustained with the advent of the H5N1 bird flu outbreaks because of H5N1's high fatality rate, although the strains currently prevalent have limited human-to-human transmission (anthroponotic) capability, or epidemicity.[164]

People who contracted flu before 1957 appeared to have some immunity to swine flu. Dr. Daniel Jernigan of the CDC has stated: "Tests on blood serum from older people showed that they had antibodies that attacked the new virus [...] That does not mean that everyone over 52 is immune, since Americans and Mexicans older than that have died of the new flu."[165]

See also

References

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. "The Universal Virus Database, version 4: Influenza A".

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/06/11/swine.flu.who/

- ^ a b "2009 H1N1 Flu ("Swine Flu") and You". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 24, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ Huffstutter, P.J. (December 5, 2009). "Don't call it 'swine flu,' farmers implore". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ a b McNeil, Jr., Donald G. (June 23, 2009). "In New Theory, Swine Flu Started in Asia, Not Mexico". The New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ^ a b Chan, Dr. Margaret (June 11, 2009). "World now at the start of 2009 influenza pandemic". World Health Organization. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Diabetes Translation (October 14, 2009). "CDC's Diabetes Program - News & Information - H1N1 Flu". CDC.gov. CDC. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ "Surveillance for Pediatric Deaths Associated with 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infection --- United States, April--August 2009". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 4, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ a b Hartocollis, Anemona (May 27, 2009). "'Underlying conditions' may add to flu worries". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ a b "Clinical features of severe cases of pandemic influenza". Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. October 16, 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ Rong-Gong Lin II (November 21, 2009). "When to take a sick child to the ER". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Updated Interim Recommendations for the Use of Antiviral Medications in the Treatment and Prevention of Influenza for the 2009-2010 Season". H1N1 Flu. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 7, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2009. Cite error: The named reference "cdc.gov" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Bronze, Michael Stuart (November 13, 2009). "H1N1 Influenza (Swine Flu)". eMedicine. Medscape. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Gale, Jason (December 4, 2009). "Clinical features of severe cases of pandemic influenza". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ a b "CDC Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Influenza Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths in the United States, April – December 12, 2009". H1N1 Flu. CDC. January 15, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Nebehay, Stephanie (January 18, 2010). "Flu pandemic easing, but risks remain: WHO". Geneva: Reuters. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ "Transcript of virtual press conference with Dr Keiji Fukuda, Assistant Director-General ad Interim for Health Security and Environment, World Health Organization" (PDF). World Health Organization. July 7, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ "Interim Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Guidance for Cruise Ships". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 5, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- ^ Kikon, Chonbenthung S. "SWINE FLU: A pandemic". The Morung Express. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ^ "Renamed swine flu certain to hit Taiwan". The China Post. April 28, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (April 28, 2009). "The naming of swine flu, a curious matter". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (April 28, 2009). "What's in a name? Governments debate 'swine flu' versus 'Mexican' flu". The Guardian. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- ^ "CDC Briefing on Investigation of Human Cases of H1N1 Flu". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 24, 2009. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Interim Guidance for 2009 H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu): Taking Care of a Sick Person in Your Home". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 5, 2009. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ Picard, Andre (November 1, 2009). "Reader questions on H1N1 answered". The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Canada. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

- ^ Whalen, Jeanne (June 15, 2009). "Flu Pandemic Spurs Queries About Vaccine". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ a b Grady, Denise (September 3, 2009). "Report Finds Swine Flu Has Killed 36 Children". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ "Clinical features of severe cases of pandemic influenza". Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 briefing note 13. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. October 16, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "What To Do If You Get Sick: 2009 H1N1 and Seasonal Flu". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 7, 2009. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/Modern+Medicine+Now/Myocarditis-Linked-to-Pandemic-H1N1-Flu-in-Childre/ArticleNewsFeed/Article/detail/656746?contextCategoryId=40137

- ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091014111549.htm

- ^ a b "Interim Guidance on Specimen Collection, Processing, and Testing for Patients with Suspected Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infection". CDC.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 13, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ a b "Influenza Diagnostic Testing During the 2009-2010 Flu Season". H1N1 Flu. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 29, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ "Interim Recommendations for Clinical Use of Influenza Diagnostic Tests During the 2009-10 Influenza Season". H1N1 Flu. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 29, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ "Evaluation of Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests for Detection of Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Virus --- United States, 2009". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 7, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ "Accuracy of rapid flu tests questioned". HealthFirst. Mid-Michigan, USA: WJRT-TV/DT. AP. December 1, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ "Could Widely Used Rapid Influenza Tests Pose A Dangerous Public Health Risk?". Maywood, Illinois, USA: Loyola Medicine. November 17, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ a b "Transcript of virtual press conference with Gregory Hartl, Spokesperson for H1N1, and Dr Nikki Shindo, Medical Officer, Global Influenza Programme, World Health Organization" (PDF). World Health Organization. November 12, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ Schnirring, Lisa (May 21, 2009). "Some immunity to novel H1N1 flu found in seniors". Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ "Swine Influenza A (H1N1) Infection in Two Children --- Southern California, March--April 2009". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 21, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Chen, Honglin; Wang, Yong; Liu, Wei; Zhang, Jinxia; Dong, Baiqing; Fan, Xiaohui; de Jong, Menno D.; Farrar, Jeremy; Riley, Steven; Guan, Yi (November 2009). "Serologic Survey of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus, Guangxi Province, China". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (11). CDC. doi:10.3201/eid1511.090868.

- ^ Emma Wilkinson (May 1, 2009). "What scientists know about swine flu". BBC News. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Donaldson LJ, Rutter PD, Ellis BM; et al. (2009). "Mortality from pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in England: public health surveillance study". BMJ. 339: b5213. PMC 2791802. PMID 20007665.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maugh, Thomas H. II (December 11, 2009). "Swine flu has hit about 1 in 6 Americans, CDC says". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 13, 2009.

- ^ Balcan, Duygu; Hu, Hao; Goncalves, Bruno; Bajardi, Paolo; Poletto, Chiara; Ramasco, Jose J.; Paolotti, Daniela; Perra, Nicola; Tizzoni, Michele (September 14, 2009). "Seasonal transmission potential and activity peaks of the new influenza A(H1N1): a Monte Carlo likelihood analysis based on human mobility". BMC Medicine. 7 (45): 29. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-7-45. arXiv:0909.2417v1.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ The New England Journal of Medicine http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/361/27/2619

- ^ Murray, Louise (November 5, 2009). "Can Pets Get Swine Flu?". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Parker-Pope, Tara (November 5, 2009). "The Cat Who Got Swine Flu". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^

"Pet dog recovers from H1N1". CBCNews. 2009-12=22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "2009 Pandemic H1N1 Influenza Presumptive and Confirmed Results" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture. December 4, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ "Use of Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Monovalent Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 28, 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

- ^ a b "Swine flu latest from the NHS". NHS Choices. NHS. NHS Knowledge Service. September 25, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2009. Cite error: The named reference "nhs-april" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b McNeil, Jr., Donald G. (September 10, 2009). "One Vaccine Shot Seen as Protective for Swine Flu". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ "Experts advise WHO on pandemic vaccine policies and strategies". World Health Organization. October 30, 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

- ^ Fox, Maggie (September 21, 2009). "Young children need 2 doses of H1N1 vaccine- US". Reuters. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (September 21, 2009). Update on NIAID Clinical Trials of 2009 H1N1 Influenza Vaccines in Children. NIAID. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

Children from 6 months to 9 years old may require two vaccinations [closed caption, app. 5 minutes into presentation]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fox, Maggie (July 24, 2009). "First defense against swine flu - seasonal vaccine". Reuters. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ McKay, Betsy (July 18, 2009). "New Push in H1N1 Flu Fight Set for Start of School". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ "Europeans urged to avoid Mexico and US as swine flu death toll exceeds 100". Guardian. April 27, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ AFP (May 6, 2009). "H1N1 virus genome: 'This is a world first'". Independent. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ "National Pandemic Flu Service". NHS, NHS Scotland, NHS Wales, DHSSPS. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ Hines, Lora (June 7, 2009). "Health officials evaluate response to swine flu". Riverside Press-Enterprise. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Stein, Rob (August 10, 2009). "Preparing for Swine Flu's Return". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Steenhuysen, Julie (June 4, 2009). "As swine flu wanes, U.S. preparing for second wave". Reuters. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Shear, Michael D.; Stein, Rob (October 24, 2009). "President Obama declares H1N1 flu a national emergency". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ Greenberg, Michael E. (2009). "Response after One Dose of a Monovalent Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Vaccine -- Preliminary Report". N Engl J Med. 361: NEJMoa0907413. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0907413.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009). "Effectiveness of 2008-09 trivalent influenza vaccine against 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) - United States, May-June 2009". MMWR. 58 (44): 1241–5. PMID 19910912.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X; et al. (2009). "Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (20): 1945–52. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0906453. PMID 19745214.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Transcript of virtual press conference with Dr Marie-Paule Kieny, Director, Initiative for Vaccine Research World Health Organization" (PDF). World Health Organization. November 19, 2009. p. 5. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ Roan, Shari (April 27, 2009). "Swine flu 'debacle' of 1976 is recalled". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "Have Egg Allergy? You May Still Be Candidate for Flu Vaccines, Says Allergist". Infection Control Today. Virgo Publishing. November 18, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ "GPs to receive swine flu vaccines". BBC News. BBC. October 26, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ Canada Probes H1N1 Vaccine Anaphylaxis Spike, Michael Smith, North American Correspondent, MedPage Today, Nov. 30, 2009.

- ^ "Transcript of virtual press conference with Kristen Kelleher, Communications Officer for pandemic (H1N1) 2009, and Dr Keiji Fukuda, Special Adviser to the Director-General on Pandemic Influenza" (PDF). World Health Organization. November 26, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "Swine flu 'a false pandemic' to sell vaccines, expert says". News.com. January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Stephanie Nebehay WHO to review its handling of H1N1 flu pandemic Reuters Tue Jan 12

- ^ Bloomberg http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601091&sid=ahj0H_RH8U68

- ^ "WHO - Influenza A(H1N1) - Travel". World Health Organization. May 7, 2009. Retrieved June 17, 2009.

- ^ "FACTBOX-Asia moves to ward off new flu virus". Reuters. February 9, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Jacobs, Karen (June 3, 2009). "Global airlines move to reduce infection risks". Reuters. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ "New CDC H1N1 Guidance for Colleges, Universities, and Institutions of Higher Education". Business Wire. August 20, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ a b George, Cindy (August 1, 2009). "Schools revamp swine flu plans for fall". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ de Vise, Daniel (August 20, 2009). "Colleges Warned About Fall Flu Outbreaks on Campus". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ "Get Smart About Swine Flu for Back-to-School". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. August 14, 2009. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ a b

Mehta, Seema (July 27, 2009). "Swine flu goes to camp. Will it go to school next?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ James C. Jr., King (August 1, 2009). "The ABC's of H1N1". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ "H1N1 Closes Hundreds of Schools Across the U.S." Fox News. October 28, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b "Business Planning". Flu.gov. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (July 25, 2009). "Swine flu could kill hundreds of thousands in U.S. if vaccine fails, CDC says". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Fiore, Marrecca (July 17, 2009). "Swine Flu: Why You Should Still Be Worried". Fox News. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ "Swine flu - HSE News Announcement". Health and Safety Executive. June 18, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ Roan, Shari (September 27, 2009). "Masks may help prevent flu, but aren't advised". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c

Roan, Shari (April 30, 2009). "Face masks aren't a sure bet against swine flu". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Face masks part of Japan fashion chic for decades". Bangkok Post. The Post Publishing. AFP. April 5, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2009. Cite error: The named reference "42bp" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Wohl, Jessica (October 20, 2009). "Flu-Related Products May Lift U.S. Makers' Profits". ABC News.com. ABC News. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ "China quarantines U.S. school group over flu concerns". CNN. May 28, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Kralev, Nicholas (June 29, 2009). "KRALEV: U.S. warns travelers of China's flu rules". The Washington Times. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ DPA (May 3, 2009). "Tensions escalate in Hong Kong's swine-flu hotel". Taipei Times. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ "Ship passengers cruisy in swine flu quarantine". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. May 28, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ El Deeb, Sarah (May 20, 2009). "Egypt Warns of Post-Hajj Swine Flu Quarantine". Cairo: ABC News. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Woolls, Daniel (April 28, 2009). "Swine flu cases in Europe; worldwide travel shaken". Taiwan News. AP. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ "Japan Swine Flu Quarantine Ends for Air Passengers". New Tang Dynasty Television. May 17, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ MIL/Sify.com (June 16, 2009). "India wants US to screen passengers for swine flu". International Reporter. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ^ Jordan, Dave (October 20, 2009). "Minnesota Pig Tests Positive for H1N1". KOTV. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ Evans, Brian (May 5, 2009). "News Conference with Minister of Health and Chief Public Health Officer". Public Health Agency of Canada. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ "Human swine flu in pigs". Effect Measure. October 20, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ "Joint FAO/WHO/OIE Statement on influenza A(H1N1) and the safety of pork" (Press release). World Health Organization. May 7, 2009. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Desmon, Stephanie (August 21, 2009). "Pork industry rues swine flu". The Baltimore Sun. Vol. 172, no. 233. pp. 1, 16. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Prevention against "swine flu" stabile in Azerbaijan: minister". Trend News Agency. April 28, 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2009.

- ^ "Cegah flu babi, pemerintah gelar rapat koordinasi". Kompas newspaper. April 27, 2009.

- ^ "Egypt orders pig cull". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. AFP. April 30, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Mayo Clinic Staff. "Influenza (flu) treatments and drugs". Diseases and Conditions. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Fever". Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ "Aspirin / Salicylates and Reyes Syndrome". National Reye's Syndrome Foundation.

- ^ Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM; et al. (2009). "Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, April-June 2009". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (20): 1935–44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0906695. PMID 19815859.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Emergency Use Authorization Granted For BioCryst's Peramivir". Reuters. PRNewswire-FirstCall. October 23, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ Cheng, Maria (August 21, 2009). "WHO: Healthy people who get swine flu don't need Tamiflu; drug for young, old, pregnant". Washington Examiner. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ BMJ Group (May 8, 2009). "Warning against buying flu drugs online". The Guardian. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 86". World Health Organization (WHO). February 5, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ "2008-2009 Influenza Season Week 39 ending October 3, 2009". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). October 9, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ Cortez, Michelle Fay (December 9, 2009). "Roche's Tamiflu Not Proven to Cut Flu Complications, Study Says". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c Jefferson, Tom; Jones, Mark; Doshi, Peter; Del Mar, Chris (December 8, 2009). "Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 339. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.: b5106. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5106. PMID 19995812. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ Godlee, Fiona (December 10, 2009). "We want raw data, now". BMJ. 339. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.: b5405. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5405.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Check, Hayden Erica (May 5, 2009). "The turbulent history of the A(H1N1) virus" (fee required). Nature. 459: 14. doi:10.1038/459014a. ISSN 1744-7933. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ Larry Pope. Smithfield Foods CEO on flu virus (flv) (Television production). MSNBC. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Cohen Jon, Enserink Martin (May 1, 2009). "As Swine Flu Circles Globe, Scientists Grapple With Basic Questions" (fee required). Science. 324 (5927): 572–3. doi:10.1126/science.324_572. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Fox, Maggie (June 11, 2009). "New flu has been around for years in pigs - study". Reuters. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ a b McNeil Jr., Donald G. (April 26, 2009). "Flu Outbreak Raises a Set of Questions". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ a b AP (May 12, 2009). "Study: Mexico Has Thousands More Swine Flu Cases". FOXNews.com. FOX News Network. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ "Swine Influenza A (H1N1) Infection in Two Children --- Southern California, March–April 2009". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 24, 2009. pp. 400–402. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ "Swine flu victim dies in Houston". Houston, Texas: KTRK-TV/DT. AP. April 29, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ "Flu Activity & Surveillance". Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 30, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ Stobbe, Mike (June 25, 2009). "US Swine Flu Cases May Have Hit 1 Million". The Huffington Post. AP. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ Ellenberg, Jordan (July 4, 2009). "Influenza Body Count". Slate. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ "Questions and Answers Regarding Estimating Deaths from Influenza in the United States". Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 4, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ "CDC week 45". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 14, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ "CDC week 34". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 30, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ "GLOBAL: No A (H1N1) cases - reality or poor lab facilities?". Reuters. May 8, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Sandman, Peter M.; Lanard, Jody (2005). "Bird Flu: Communicating the Risk". Perspectives in Health Magazine. 10 (2).

- ^ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 briefing note 3" (in 2009-07-16). World Health Organization. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c "Influenza : Fact sheet". World Health Organization. March 2003. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ Dushoff, J.; Plotkin, J. B.; Viboud, C.; Earn, D. J. D.; Simonsen, L. (2006). "Mortality due to Influenza in the United States -- An Annualized Regression Approach Using Multiple-Cause Mortality Data". American Journal of Epidemiology. 163: 181–7. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj024. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

The regression model attributes an annual average of 41,400 (95% confidence interval: 27,100, 55,700) deaths to influenza over the period 1979–2001.

- ^ Kaplan, Karen (September 18, 2009). "Swine flu's tendency to strike the young is causing confusion". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Kilbourne, ED; Zhang, Yan B.; Lin, Mei-Chen (January 2006). "Influenza pandemics of the 20th century". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 299. doi:10.1177/1461444804041438. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Greger, Dr. Michael (August 26, 2009). "CDC Confirms Ties to Virus First Discovered in U.S. Pig Factories". The Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on September 26, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sternberg, Steve (May 26, 2009). "CDC expert says flu outbreak is dying down -- for now". USA Today. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ David M. Morens, Jeffery K. Taubenberger, and Anthony S. Fauci (October 1, 2008). "Predominant Role of Bacterial Pneumonia as a Cause of Death in Pandemic Influenza: Implications for Pandemic Influenza Preparedness". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (7): 962–970. doi:10.1086/591708. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Hsieh, Yu-Chia (January 2006). "Influenza pandemics: past present and future" (PDF). Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 105 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60102-9. PMID 16440064. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Taubenberger, Jeffery K. (January 2006). "1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics". Emerging Infectious Diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (ed.). "1: The Story of Influenza". The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. pp. 60–61.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Patterson, KD (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bull Hist Med. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Ten things you need to know about pandemic influenza". World Health Organization. October 14, 2005. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Taubenberger, JK; Morens, DM (January 2006). "1918 influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ "WHO Europe - Influenza". World Health Organization. June 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- ^ Reuters (September 17, 2009). "H1N1 fatality rates comparable to seasonal flu". The Malaysian Insider. Washington, D.C., USA. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 76". Global Alert and Response (GAR). World Health Organization. November 27, 2009. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 77". Global Alert and Response (GAR). World Health Organization. December 4, 2009. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ Triggle, Nick (December 10, 2009). "Swine flu less lethal than feared". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ Kilbourne, Edwin D. (January 2006). "Influenza Pandemics of the 20th Century" (PDF). Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1). CDC: 9–14. PMID 16494710. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ Brown, David (April 29, 2009). "System set up after SARS epidemic was slow to alert global authorities". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Beigel JH, Farrar J, Han AM, Hayden FG, Hyer R, de Jong MD, Lochindarat S, Nguyen TK, Nguyen TH, Tran TH, Nicoll A, Touch S, Yuen KY; Writing Committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) Consultation on Human Influenza A/H5 (September 29, 2005). "Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (13): 1374–85. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052211. PMID 16192482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ McNeil Jr., Donald G. (May 20, 2009). "U.S. Says Older People Appear Safer From New Flu Strain". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

Further reading

- Cannell, JJ; Zasloff, M; Garland, CF; Scragg, R; Giovannucci, E (February 25, 2008). "On the epidemiology of influenza". Virology Journal. 5 (29): 29. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-29. PMC 2279112. PMID 18298852.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author2=and|last2=specified (help); More than one of|author3=and|last3=specified (help); More than one of|author4=and|last4=specified (help); More than one of|author5=and|last5=specified (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Smith, Gavin; Vijaykrishna, D; Bahl, J; Lycett, SJ; Worobey, M; Pybus, OG; Ma, SK; Cheung, CL; Raghwani, J (June 25, 2009). "Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic". Nature. 459 (459): 1122–1125. doi:10.1038/nature08182. PMID 19516283.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Soundararajan, Venkataramanan; Tharakaraman, K; Raman, R; Raguram, S; Shriver, Z; Sasisekharan, V; Sasisekharan, R (2009). "Extrapolating from sequence — the 2009 H1N1 'swine' influenza virus" (PDF). Nature Biotechnology. 27 (6): 510–513. doi:10.1038/nbt0609-510. PMID 19513050.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Introduction and Transmission of 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Virus --- Kenya, June--July 2009". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). October 23, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

External links

- Influenza: H1N1 at Curlie

- Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 at the World Health Organization

- International Society for Infectious Diseases PROMED-mail news updates

- H1N1 Flu Resource Centre of The Lancet

- Influenza Research Database – Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- CDC 2009 H1N1 Influenza Vaccine Supply Status

- The H1N1 Pandemic and Global Health Security, Dean Julio Frenk, 2009-09-17

- Graphical Image of the viral makeup of the 2009 pandemic h1n1 virus – NEJM

Europe

- Health-EU Portal EU response to influenza

- [1] at the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)

- European Commission - Public Health EU coordination on Pandemic (H1N1) 2009.

- UK National Pandemic Flu Service

- Official UK government information on swine flu from Directgov

- Official swine flu advice and latest information from the UK National Health Service

- Human/Swine A/H1N1 Influenza Origins and Evolution - Analysis of genetic data for the origin and evolution of swine flu virus.

North America

- Health Canada flu portal

- Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) Swine Influenza portal

- H1N1 Influenza (Flu) portal at the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

- US Government swine, avian and pandemic flu portal

- Medical Encyclopedia Medline Plus: Swine Flu

- Swine Flu Outbreak, Influenza Virus Resource - Sequences and related resources (GenBank, NCBI)