Emancipation Proclamation: Difference between revisions

Wtmitchell (talk | contribs) →International impact: Add cites |

→External links: added a link to a digitized copy of the Proclamation |

||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

{{wikisource}} |

{{wikisource}} |

||

{{Commons category}} |

{{Commons category}} |

||

*[http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=C.160.c.4.(1)_f001r A zoomable image of the Leland-Boker authorized edition of the Emancipation Proclamation held by the British Library] |

|||

*[http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=290 Lesson plan on Emancipation Proclamation from EDSITEment NEH] |

*[http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=290 Lesson plan on Emancipation Proclamation from EDSITEment NEH] |

||

*[http://www.brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/documents/SlaveryAndJustice.pdf Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice] |

*[http://www.brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/documents/SlaveryAndJustice.pdf Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice] |

||

Revision as of 12:28, 24 November 2011

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly all the rest freed as Union armies advanced. The Proclamation did not compensate the owners; it did not make the ex-slaves, called Freedmen, citizens.[1]

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln announced that he would issue a formal emancipation of all slaves in any state of the Confederate States of America that did not return to Union control by January 1, 1863. None returned and the actual order, signed and issued January 1, 1863, took effect except in locations where the Union had already mostly regained control. The Proclamation made abolition a central goal of the war (in addition to reunion), outraged white Southerners who envisioned a race war, angered some Northern Democrats, energized anti-slavery forces, and weakened forces in Europe that wanted to intervene to help the Confederacy.[2]

Total abolition of slavery was finalized by the Thirteenth Amendment which took effect in December 1865.

Authority

Lincoln issued the Proclamation under his authority as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy" under Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution.[3] As such, he had the martial power to suspend civil law in those states which were in rebellion. He did not have Commander-in-Chief authority over the four slave-holding states that had not seceded: Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland and Delaware. The Emancipation Proclamation was never challenged in court. To ensure the abolition of slavery everywhere in the U.S., Lincoln pushed for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. Congress passed it by the necessary 2/3 vote in February 1865 and it was ratified by the states by December 1865.[4]

Coverage

The Proclamation applied only in ten states that were still in rebellion in 1863, thus it did not cover the nearly 500,000 slaves in the slave-holding border states (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland or Delaware) which were Union states — those slaves were freed by separate state and federal actions. The state of Tennessee had already mostly returned to Union control, so it was not named and was exempted. Virginia was named, but exemptions were specified for the 48 counties then in the process of forming the new state of West Virginia, seven additional Tidewater[clarification needed] counties individually named, and two cities. Also specifically exempted were New Orleans and 13 named parishes of Louisiana, all of which were also already mostly under Federal control at the time of the Proclamation. These exemptions left unemancipated an additional 300,000 slaves.[5]

The Emancipation Proclamation was incorrectly ridiculed for freeing only the slaves over which the Union had no power. In fact, over 20,000 to 50,000 were freed the day it went into effect[6] in parts of nine of the ten states to which it applied (Texas being the exception).[7] In every Confederate state (except Tennessee and Texas), the Proclamation went into immediate effect in Union-occupied areas and at least 20,000 slaves[6][7] were freed at once on January 1, 1863.

Additionally, the Proclamation provided the legal framework for the emancipation of nearly all four million slaves as the Union armies advanced, and committed the Union to ending slavery, which was a controversial decision even in the North. Hearing of the Proclamation, more slaves quickly escaped to Union lines as the Army units moved South. As the Union armies advanced through the Confederacy, thousands of slaves were freed each day until nearly all (approximately 4 million, according to the 1860 census)[8] were freed by July 1865.

While the Proclamation had freed most slaves as a war measure, it had not made slavery illegal. Of the states that were exempted from the Proclamation, Maryland,[9] Missouri,[10] and Tennessee[11] prohibited slavery before the war ended; however, in Kentucky, Delaware,[12] and West Virginia slavery continued to be legal[citation needed] until December 18, 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment went into effect.

Background

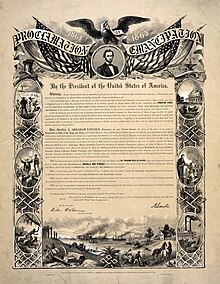

(People in the image are clickable.)

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required individuals to return runaway slaves to their owners. During the war, Union generals such as Benjamin Butler, declared that slaves in occupied areas were contraband of war and accordingly refused to return them.[14] This decision was controversial because it implied recognition of the Confederacy as a separate nation under international law, a notion that Lincoln steadfastly denied. As a result, he did not promote the contraband designation. Some generals also declared the slaves under their jurisdiction to be free and were replaced when they refused to rescind such declarations.

In January 1862, Thaddeus Stevens, the Republican leader in the House, called for total war against the rebellion to include emancipation of slaves, arguing that emancipation, by forcing the loss of enslaved labor, would ruin the rebel economy. On March 13, 1862, Congress approved a "Law Enacting an Additional Article of War" which stated that from that point onward it was forbidden for Union Army officers to return fugitive slaves to their owners.[15] On April 10, 1862, Congress declared that the federal government would compensate slave owners who freed their slaves. Slaves in the District of Columbia were freed on April 16, 1862, and their owners were compensated.

On June 19, 1862, Congress prohibited slavery in United States territories, and President Lincoln quickly signed the legislation. By this act, they opposed the 1857 opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott Case that Congress was powerless to regulate slavery in U.S. territories.[16][17] This joint action by Congress and President Lincoln also rejected the notion of popular sovereignty that had been advanced by Stephen A. Douglas as a solution to the slavery controversy, while completing the effort begun by Thomas Jefferson in 1784 to confine slavery within the borders of the states.[18][19]

In July 1862, Congress passed and Lincoln signed the "Second Confiscation Act." It purported to liberate slaves held by "rebels",[20] but Lincoln took the position that Congress lacked power to free slaves within the borders of the states unless Lincoln as commander in chief deemed it a proper military measure.[21] And that Lincoln would soon do.

Abolitionists had long been urging Lincoln to free all slaves. A mass rally in Chicago on September 7, 1862, demanded an immediate and universal emancipation of slaves. A delegation headed by William W. Patton met the President at the White House on September 13. Lincoln had declared in peacetime that he had no constitutional authority to free the slaves. Even used as a war power, emancipation was a risky political act. Public opinion as a whole was against it.[22] There would be strong opposition among Copperhead Democrats and an uncertain reaction from loyal border states. Delaware and Maryland already had a high percentage of free blacks: 91.2% and 49.7%, respectively, in 1860.[23]

Drafting and issuance of the proclamation

Lincoln first discussed the proclamation with his cabinet in July 1862. He believed he needed a Union victory on the battlefield so his decision would appear positive and strong. The Battle of Antietam, in which Union troops turned back a Confederate invasion of Maryland, gave him such an opportunity. On September 22, 1862, five days after Antietam, Lincoln called his cabinet into session and issued the Preliminary Proclamation. According to Civil War historian James M. McPherson, Lincoln told Cabinet members that he had made a covenant with God, that if the Union drove the Confederacy out of Maryland, he would issue the Emancipation Proclamation.[24][25] Lincoln had first shown an early draft of the proclamation to his Vice president Hannibal Hamlin,[26] an ardent abolitionist, who was more often kept in the dark on presidential decisions. The final proclamation was issued January 1, 1863. Although implicitly granted authority by Congress, Lincoln used his powers as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, "as a necessary war measure" as the basis of the proclamation, rather than the equivalent of a statute enacted by Congress or a constitutional amendment.

Initially, the Emancipation Proclamation effectively freed only a small percentage of the slaves, those who were behind Union lines in areas not exempted. Most slaves were still behind Confederate lines or in exempted Union-occupied areas. Secretary of State William H. Seward commented, "We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free." Had any slave state ended its secession attempt before January 1, 1863, it could have kept slavery, at least temporarily. The Proclamation only gave Lincoln the legal basis to free the slaves in the areas of the South that were still in rebellion. However, it also took effect as the Union armies advanced into the Confederacy.

The Emancipation Proclamation also allowed for the enrollment of freed slaves into the United States military. During the war nearly 200,000 blacks, most of them ex-slaves, joined the Union Army. Their contributions gave the North additional manpower that was significant in winning the war. The Confederacy did not allow slaves in their army as soldiers until the final months before its defeat.

Though the counties of Virginia that were soon to form West Virginia were specifically exempted from the Proclamation (Jefferson County being the only exception), a condition of the state's admittance to the Union was that its constitution provide for the gradual abolition of slavery. Slaves in the border states of Maryland and Missouri were also emancipated by separate state action before the Civil War ended. In Maryland, a new state constitution abolishing slavery in the state went into effect on November 1, 1864. In early 1865, Tennessee adopted an amendment to its constitution prohibiting slavery.[27][28] Slaves in Kentucky and Delaware were not emancipated until the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified.

Implementation

The Proclamation was issued in two parts. The first part, issued on September 22, 1862, was a preliminary announcement outlining the intent of the second part, which officially went into effect 100 days later on January 1, 1863, during the second year of the Civil War. It was Abraham Lincoln's declaration that all slaves would be permanently freed in all areas of the Confederacy that had not already returned to federal control by January 1863. The ten affected states were individually named in the second part (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina). Not included were the Union slave states of Maryland, Delaware, Missouri and Kentucky. Also not named was the state of Tennessee, which was at the time more or less evenly split between Union and Confederacy. Specific exemptions were stated for areas also under Union control on January 1, 1863, namely 48 counties that would soon become West Virginia, seven other named counties of Virginia including Berkeley and Hampshire counties which were soon added to West Virginia, New Orleans and 13 named parishes nearby.

Union-occupied areas of the Confederate states where the proclamation was put into immediate effect by local commanders included Winchester, Virginia,[29] Corinth, Mississippi,[30] the Sea Islands along the coasts of the Carolinas and Georgia,[31] Key West, Florida,[32] and Port Royal, South Carolina.[33]

Immediate impact

It is common to encounter a claim that the Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free a single slave. As a result of the Proclamation, many slaves were freed during the course of the war, beginning with the day it took effect. Eyewitness accounts at places such as Hilton Head, South Carolina,[34] and Port Royal, South Carolina,[33] record celebrations on January 1 as thousands of blacks were informed of their new legal status of freedom.

Estimates of the number of slaves freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation are uncertain. One contemporary estimate put the 'contraband' population of Union-occupied North Carolina at 10,000, and the Sea Islands of South Carolina also had a substantial population. Those 20,000 slaves were freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation."[6] This Union-occupied zone where freedom began at once included parts of eastern North Carolina, the Mississippi Valley, northern Alabama, the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, a large part of Arkansas, and the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina.[35] Although some counties of Union-occupied Virginia were exempted from the Proclamation, the lower Shenandoah Valley, and the area around Alexandria were covered.[6]

Booker T. Washington, as a boy of 9 in Virginia, remembered the day in early 1865:[36]

As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom.... Some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.

The Emancipation took place without violence by masters or ex-slaves. The proclamation represented a shift in the war objectives of the North—reuniting the nation was no longer the only goal. It represented a major step toward the ultimate abolition of slavery in the United States and a "new birth of freedom".

Runaway slaves who had escaped to Union lines had previously been held by the Union Army as "contraband of war" under the Confiscation Acts; when the proclamation took effect, they were told at midnight that they were free to leave. The Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia had been occupied by the Union Navy earlier in the war. The whites had fled to the mainland while the blacks stayed. An early program of Reconstruction was set up for the former slaves, including schools and training. Naval officers read the proclamation and told them they were free.

In the military, reaction to the proclamation varied widely, with some units nearly ready to mutiny in protest. Some desertions were attributed to it. Other units were inspired by the adoption of a cause that ennobled their efforts, such that at least one unit took up the motto "For Union and Liberty".

Slaves had been part of the "engine of war" for the Confederacy. They produced and prepared food; sewed uniforms; repaired railways; worked on farms and in factories, shipping yards, and mines; built fortifications; and served as hospital workers and common laborers. News of the Proclamation spread rapidly by word of mouth, arousing hopes of freedom, creating general confusion, and encouraging thousands to escape to Union lines.

Robert E. Lee saw the Emancipation Proclamation as a way for the Union to bolster the number of soldiers it could place on the field, making it imperative for the Confederacy to increase their own numbers.

Writing on the matter after the sack of Fredericksburg, Lee wrote "In view of the vast increase of the forces of the enemy, of the savage and brutal policy he has proclaimed, which leaves us no alternative but success or degradation worse than death, if we would save the honor of our families from pollution, our social system from destruction, let every effort be made, every means be employed, to fill and maintain the ranks of our armies, until God, in his mercy, shall bless us with the establishment of our independence."[37] Lee's request for a drastic increase of troops would go unfulfilled.

Political impact

The Proclamation was immediately denounced by Copperhead Democrats who opposed the war and advocated restoring the union by allowing slavery. Horatio Seymour, while running for the governorship of New York, cast the Emancipation Proclamation as a call for slaves to commit extreme acts of violence on all white southerners, he said it was "a proposal for the butchery of women and children, for scenes of lust and rapine, and of arson and murder, which would invoke the interference of civilized Europe."[40] The Copperheads also saw the Proclamation as an unconstitutional abuse of Presidential power, editor Henry A. Reeves wrote in Greenport's Republican Watchman that "In the name of freedom of Negroes, [the proclamation] imperils the liberty of white men; to test a utopian theory of equality of races which Nature, History and Experience alike condemn as monstrous, it overturns the Constitution and Civil Laws and sets up Military Usurpation in their Stead."[40]

Racism remained pervasive on both sides of the conflict and many in the North only supported the war as an effort to force the south back into the Union. The promises of many Republican politicians that the war was to restore the Union and not about black rights or ending slavery were now declared lies by their opponents citing the Proclamation. Copperhead David Allen spoke to a rally in Columbiana, Ohio, stating "I have told you that this war is carried on for the Negro. There is the proclamation of the President of the United States. Now fellow Democrats I ask you if you are going to be forced into a war against your Brethren of the Southern States for the Negro. I answer No!"[40] The Copperheads saw the Proclamation as irrefutable proof of their position and the beginning of a political rise for their members; in Connecticut H.B. Whiting wrote that the truth was now plain even to "those stupid thick-headed persons who persisted in thinking that the President was a conservative man and that the war was for the restoration of the Union under the Constitution."[40]

War Democrats who rejected the Copperhead position within their party, found themselves in a quandary. While throughout the war they had continued to espouse the racist positions of their party and their disdain of the concerns of slaves, they did see the Proclamation as a viable military tool against the South and worried that opposing it might demoralize troops in the Union army. The question would continue to trouble them and eventually lead to a split within their party as the war progressed.[40]

Lincoln further alienated many in the Union two days after issuing the preliminary copy of the Emancipation Proclamation by suspending habeas corpus. His opponents linked these two actions in their claims that he was becoming a despot. In light of this and a lack of military success for the Union armies, many War Democrat voters who had previously supported Lincoln turned against him and joined the Copperheads in the off-year elections held in October and November.[40]

In the 1862 elections, the Democrats gained 28 seats in the House as well as the governorship of New York. Lincoln’s friend Orville Hickman Browning told the President that the Proclamation and the suspension of habeas corpus had been "disastrous" for his party by handing the Democrats so many weapons. Lincoln made no response. Copperhead William Javis of Connecticut pronounced the election the "beginning of the end of the utter downfall of Abolitionism."[40]

Historians James M. McPherson and Allan Nevins state that though the results look very troubling, they could be seen favorably by Lincoln; his opponents did well only in their historic strongholds and "at the national level their gains in the House were the smallest of any minority party’s in an off-year election in nearly a generation. Michigan, California, and Iowa all went Republican...Moreover, the Republicans picked up five seats in the Senate."[40] McPherson states "If the election was in any sense a referendum on emancipation and on Lincoln’s conduct of the war, a majority of Northern voters endorsed these policies."[40]

International impact

As Lincoln had hoped, the Proclamation turned foreign popular opinion in favor of the Union by adding the ending of slavery as a goal of the war. That shift ended the Confederacy's hopes of gaining official recognition, particularly from the United Kingdom, which had abolished slavery.[41] Prior to Lincoln's decree, Britain's actions had favored the Confederacy, especially in its provision of British-built warships such as the CSS Alabama and CSS Florida.[42] Furthermore, the North's determination to win at all costs was creating problems diplomatically; the Trent Affair of late 1861 had caused severe tensions between the United States and Great Britain. For the Confederacy to receive official recognition by foreign powers would have been a further blow to the Union cause.

With the war now cast in terms of freedom against slavery, British or French support for the Confederacy would look like support for slavery, which both of these nations had abolished. As Henry Adams noted, "The Emancipation Proclamation has done more for us than all our former victories and all our diplomacy." In Italy, Giuseppe Garibaldi hailed Lincoln as "the heir of the aspirations of John Brown". On August 6, 1863 Garibaldi wrote to Lincoln: Posterity will call you the great emancipator, a more enviable title than any crown could be, and greater than any merely mundane treasure.[43]

Alan Van Dyke, a representative for workers from Manchester, England, wrote to Lincoln saying, "We joyfully honor you for many decisive steps toward practically exemplifying your belief in the words of your great founders: 'All men are created free and equal.'" The Emancipation Proclamation served to ease tensions with Europe over the North's conduct of the war, and combined with the recent failed Southern offensive at Antietam to cut off any practical chance for the Confederacy to receive international support in the war.

Gettysburg Address

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address in November 1863 made indirect reference to the Proclamation and the ending of slavery as a war goal with the phrase "new birth of freedom". The Proclamation solidified Lincoln's support among the rapidly growing abolitionist element of the Republican Party and ensured they would not block his re-nomination in 1864.[44]

Postbellum

Near the end of the war, abolitionists were concerned that the Emancipation Proclamation would be construed solely as a war act, Lincoln's original intent, and no longer apply once fighting ended. They were also increasingly anxious to secure the freedom of all slaves, not just those freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Thus pressed, Lincoln staked a large part of his 1864 presidential campaign on a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery uniformly throughout the United States. Lincoln's campaign was bolstered by separate votes in both Maryland and Missouri to abolish slavery in those states. Maryland's new constitution abolishing slavery took effect in November 1864. Slavery in Missouri was ended by executive proclamation of its governor, Thomas C. Fletcher, on January 11, 1865.

Winning re-election, Lincoln pressed the lame duck 38th Congress to pass the proposed amendment immediately rather than wait for the incoming 39th Congress to convene. In January 1865, Congress sent to the state legislatures for ratification what became the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery in all U.S. states and territories. The amendment was ratified by the legislatures of enough states by December 6, 1865, and proclaimed 12 days later. There were about 40,000 slaves in Kentucky and 1,000 in Delaware who were liberated then.[8]

Legacy

In the years after Lincoln's death, his action in the proclamation was lauded. The anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated as a black holiday for more than 50 years; the holiday of Juneteenth was created in some states to honor it.[45] In 1913, the 50th anniversary of the Proclamation, there were particularly large celebrations.

As the years went on and American life continued to be deeply unfair towards blacks, cynicism towards Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation increased. Some 20th century black intellectuals, including W. E. B. Du Bois, James Baldwin and Julius Lester, described the proclamation as essentially worthless. Perhaps the strongest attack was Lerone Bennett's Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream (2000), which claimed that Lincoln was a white supremacist who issued the Emancipation Proclamation in lieu of the real racial reforms for which radical abolitionists pushed. In his Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, Allen C. Guelzo noted the professional historians' lack of substantial respect for the document, since it has been the subject of few major scholarly studies. He argued that Lincoln was America's "last Enlightenment politician"[46] and as such was dedicated to removing slavery strictly within the bounds of law.

Other historians have given more credit to Lincoln for what he accomplished within the tensions of his cabinet and a society at war, for his own growth in political and moral stature, and for the promise he held out to the slaves.[47] More might have been accomplished if he had not been assassinated. As Eric Foner wrote:

Lincoln was not an abolitionist or Radical Republican, a point Bennett reiterates innumerable times. He did not favor immediate abolition before the war, and held racist views typical of his time. But he was also a man of deep convictions when it came to slavery, and during the Civil War displayed a remarkable capacity for moral and political growth.[48]

See also

- Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves – 1863 statute

- African Americans in the 1960s

- History of slavery in Kentucky

- History of slavery in Missouri

- Slavery Abolition Act 1833 – an act passed by the British parliament abolishing slavery in British colonies with compensation to the owners

- Timeline of the African-American Civil Rights Movement

- War Governors' Conference – gave Lincoln the much needed political support to issue the Proclamation

Notes

- ^ Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2010) pp 239-42

- ^ Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: vol 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863 (1960) pp 231-41, 273

- ^ Crowther p. 651

- ^ Allen C. Guelzo. ""The Great Event of the Nineteenth Century": Lincoln Issues the Emancipation Proclamation". The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved May 7, 2011].

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Foner (2010) pp.241-242

- ^ a b c d Keith Poulter, "Slaves Immediately Freed by the Emancipation Proclamation", North & South vol. 5 no. 1 (December 2001), p. 48

- ^ a b William C. Harris, "After the Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln's Role in the Ending of Slavery", North & South vol. 5 no. 1 (December 2001), map on p. 49

- ^ a b "Census, Son of the South". sonofthesouth.net. 1860.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland Historical List: Constitutional Convention, 1864". November 1, 1864.

- ^ "Missouri abolishes slavery". January 11, 1865.

- ^ "TENNESSEE STATE CONVENTION: Slavery Declared Forever Abolished". NY Times. January 14, 1865.

- ^ "Slavery in Delaware".

- ^ "Art & History: First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln". U.S. Senate. Retrieved August 2, 2013. Lincoln met with his cabinet on July 22, 1862, for the first reading of a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation.

- ^ Adam Goodheart (April 1, 2011). "How Slavery Really Ended in America". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ U.S., Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America. Vol. 12. Boston. 1863. p. 354.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Guminski, Arnold. The Constitutional Rights, Privileges, and Immunities of the American People, page 241 (2009).

- ^ Richardson, Theresa and Johanningmeir, Erwin. Race, ethnicity, and education, page 129 (IAP 2003).

- ^ Montgomery, David. The student's American history, page 428 (Ginn & Co. 1897).

- ^ Keifer, Joseph. Slavery and Four Years of War, p. 109 (Echo Library 2009).

- ^ "The Second Confiscation Act, July 17, 1862". History.umd.edu. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Donald, David. Lincoln, page 365 (Simon and Schuster 1996).

- ^ Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, 2004, pg. 18

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1994, p.82

- ^ McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom, (1988), p557

- ^

Carpenter, Frank B (1866). Six Months at the White House. p. 90. ISBN 9781429015271. Retrieved 2010-02-20. as reported by Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon Portland Chase, September 22, 1862. Others present used the word resolution instead of vow to God.

Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911), 1:143, reported that Lincoln made a covenant with God that if God would change the tide of the war, Lincoln would change his policy toward slavery. See also Nicolas Parrillo, "Lincoln's Calvinist Transformation: Emancipation and War", Civil War History (September 1, 2000). - ^ "Bangor In Focus: Hannibal Hamlin". Bangorinfo.com. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ "Freedmen and Southern Society Project: Chronology of Emancipation". History.umd.edu. 2009-12-08. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ "TSLA: This Honorable Body: African American Legislators in 19th Century Tennessee". State.tn.us. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Richard Duncan, Beleaguered Winchester: A Virginia Community at War (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 2007), pp. 139–40

- ^ Ira Berlin et al., eds, Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation 1861–1867, Vol. 1: The Destruction of Slavery (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 260

- ^ William Klingaman, Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861–1865 (NY: Viking Press, 2001), p. 234

- ^ "Important From Key West", New York Times February 4, 1863, p. 1

- ^ a b Own, Our (January 9, 1863). "Interesting from Port Royal". The New York Times. p. 2.

- ^ "News from South Carolina: Negro Jubilee at Hilton Head", New York Herald, January 7, 1863, p.5

- ^ Harris, "After the Emancipation Proclamation", p. 45

- ^ Up from Slavery (1901) pp 19-21

- ^ Shelby Foote (1963). The Civil War, a Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian. Vol. Volume 2. Random House.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "Abe Lincoln's Last Card".

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (2000). Abraham Lincoln, a press portrait: his life and times from the original newspaper documents of the Union, the Confederacy, and Europe. Fordham Univ Press. ISBN 9780823220625.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jennifer L. Weber (2006). Copperheads: the rise and fall of Lincoln's opponents in the North. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Robert E. May (1995). "History and Mythology : The Crisis over British Intervention in the Civil War". The Union, the Confederacy, and the Atlantic rim. Purdue University Press. pp. 29–68. ISBN 978-1-55753-061-5.

- ^ W. Craig Gaines (2008). Encyclopedia of Civil War shipwrecks. LSU Press. pp. 36. ISBN 978-0-8071-3274-6.

- ^ Mack Smith, p. 72

- ^ Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: vol 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863 (1960)

- ^ Guelzo, p. 244.

- ^ Guelzo, p. 3.

- ^ Doris Kearns Goodwin, A Team of Rivals, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005

- ^ Foner, Eric (April 9, 2000). "review of Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream by Lerone Bennett, Jr". Los Angeles Times Book Review. Retrieved Jun 30, 2008.

References

- Herman Belz, Emancipation and Equal Rights: Politics and Constitutionalism in the Civil War Era (1978)

- Crowther, Edward R. “Emancipation Proclamation”. in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. Heidler, David S. and Heidler, Jeanne T. (2000) ISBN 0-393-04758-X

- Christopher Ewan, "The Emancipation Proclamation and British Public Opinion" The Historian, Vol. 67, 2005

- John Hope Franklin, The Emancipation Proclamation (1963)

- Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (W.W. Norton, 2010)

- Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (2004)

- Guelzo, Allen C. "How Abe Lincoln Lost the Black Vote: Lincoln and Emancipation in the African American Mind," Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association (2004) 25#1 online edition

- Harold Holzer, Edna Greene Medford, and Frank J. Williams. The Emancipation Proclamation: Three Views (2006)

- Howard Jones, Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War (1999)

- Mitch Kachun, Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808–1915 (2003)

- Mack Smith, Denis (1969). Garibaldi (Great Lives Observed). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

- McPherson, James M. Ordeal by Fire: the Civil War and Reconstruction (2001 [3rd ed.]), esp. pp. 316–321.

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union: vol 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863 (1960)

- Roger L. Ransom and Richard Sutch: One Kind of Freedom – The Economic Consequences of Emancipation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1977 ISBN 0-521-29203-4

- C. Peter Ripley, Roy E. Finkenbine, Michael F. Hembree, Donald Yacovone, Witness for Freedom: African American Voices on Race, Slavery, and Emancipation (1993)

- Silvana R. Siddali, From Property To Person: Slavery And The Confiscation Acts, 1861–1862 (2005)

- John Syrett. Civil War Confiscation Acts: Failing to Reconstruct the South (2005)

- Alexander Tsesis, We Shall Overcome: A History of Civil Rights and the Law (2008)

- Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2001)

External links

- A zoomable image of the Leland-Boker authorized edition of the Emancipation Proclamation held by the British Library

- Lesson plan on Emancipation Proclamation from EDSITEment NEH

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- Teaching resources about Slavery and Abolition on blackhistory4schools.com

- Text and images of the Emancipation Proclamation from the National Archives

- Online Lincoln Coloring Book for Teachers and Students

- Emancipation Proclamation and related resources at the Library of Congress

- Scholarly article on rhetoric and the Emancipation Proclamation

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Emancipation Proclamation

- First Edition Emancipation Proclamation in 1862 Harper's Weekly

- Chronology of Emancipation during the Civil War

- "Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation"

- Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation at the New York State Library – Images and transcript of Lincoln's original manuscript of the preliminary proclamation.

- 1865 NY Times article Sketch of its History by Lincoln's portrait artist