Death by burning: Difference between revisions

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

| url=http://veja.abril.com.br/300102/p_094.html |accessdate=8 October 2007}}</ref> |

| url=http://veja.abril.com.br/300102/p_094.html |accessdate=8 October 2007}}</ref> |

||

[[Image:Burning of a Widow.jpg|thumb|''“Ceremony of Burning a Hindu Widow with the Body of her Late Husband”'', from ''Pictorial History of China and India'', 1851.]] |

[[Image:Burning of a Widow.jpg|thumb|''“Ceremony of Burning a Hindu Widow with the Body of her Late Husband”'', from ''Pictorial History of China and India'', 1851.]] |

||

A former Soviet [[GRU|Main Intelligence Directorate]] officer writing under the alias [[Victor Suvorov]], described in his book [[ |

A former Soviet [[GRU|Main Intelligence Directorate]] officer writing under the alias [[Victor Suvorov]], described in his book [[Aquarium (Suvorov)|Aquarium]] a Soviet traitor being burnt alive in a [[crematorium]].<ref>Suworow, Viktor. ''GRU – Die Speerspitze: Was der KGB für die Polit-Führung, ist die GRU für die Rote Armee.'' 3., korr. Aufl. Solingen: Barett, 1995. ISBN 3-924753-18-0. {{de icon}}</ref> There has been some speculation<ref>http://www.tnr.com/article/politics/the-newer-meaning-treason</ref> that the identity of this officer was [[Oleg Penkovsky]], however during his radio interview to Russian station [[Echo of Moscow]] Vladimir Rezun (alias Victor Suvorov) denied this, saying "I never mentioned it was Penkovsky" <ref>http://www.echo.msk.ru/programs/hrushev/655886-echo/</ref> No executed [[GRU]] traitors (Penkovsky aside) are known matching scant Suvorov's description given in "Aquarium"<ref>http://lib.ru/WSUWOROW/akwarium.txt</ref><ref>http://www.scribd.com/doc/46398733/Suvorov-Aquarium-The-Career-and-Defection-of-a-Soviet-Spy-1985</ref> (handsome manly face, worked in GRU in a rank of colonel). |

||

During the 1980 [[New Mexico State Penitentiary riot]], a number of inmates were burnt to death by fellow inmates, who used [[blow torch]]es. |

During the 1980 [[New Mexico State Penitentiary riot]], a number of inmates were burnt to death by fellow inmates, who used [[blow torch]]es. |

||

Revision as of 07:41, 21 July 2012

Deliberately causing death through the effects of combustion has a long history as a form of capital punishment. Many societies have employed it as an execution method for crimes such as treason, heresy, and witchcraft.

The particular form of execution by burning in which the condemned is bound to a large stake is more commonly called burning at the stake. Death by burning fell into disfavour amongst governments in the late 18th century.

Cause of death

If the fire was large (for instance, when a large number of prisoners were executed at the same time), death often came from carbon monoxide poisoning before flames actually caused harm to the body. If the fire was small, however, the convict would burn for some time until death from heatstroke, shock, the loss of blood and/or simply the thermal decomposition of vital body parts.

When this method of execution was applied with skill, the condemned’s body would burn progressively in the following sequence: calves, thighs and hands, torso and forearms, breasts, upper chest, face; and then finally death. On other occasions, people died from suffocation with only their calves on fire. Several records report that victims took over 2 hours to die. In many burnings a rope was attached to the convict’s neck passing through a ring on the stake and they were simultaneously strangled and burnt. In later years in England some burnings only took place after the convict had already hanged for half an hour. In many areas in England the condemned woman (men were hanged, drawn, and quartered) was seated astride a small seat called the saddle which was fixed half way up a permanently positioned iron stake. The stake was about 4 metres high and had chains hanging from it to hold the condemned woman still during her punishment. Having been taken to the place of execution in a cart with her hands firmly tied in front of her and wearing just a thin shift she was lifted over the executioner’s shoulder and carried up a ladder against the stake to be sat astride the saddle. The chains were then fastened and sometimes she was painted with pitch which was supposed to help the fire burn her more quickly.

Historical usage

The Greek tyrant Phalaris, of Akragas in Sicily, is said to have roasted his enemies alive in a brazen bull; it was devised for him by a workman named Perillus or Perilaos, who made it so that the screams of the victims sounded like the roaring of a bull; when Perillus asked for his reward, he became the first victim.[1] Phalaris was later executed in his brazen bull.

Burning was used as a means of execution in many ancient societies. According to ancient reports, Roman authorities executed many of the early Christian martyrs by burning, sometimes by means of the tunica molesta, a flammable tunic.

Also Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion, one of the Jewish Ten Martyrs executed for defying Emperor Hadrian’s edicts against practice of the Jewish religion, is reported to have been burnt at the stake. As narrated in the Talmud, ben Teradion was placed on a pyre of green brush; fire was set to it, and wet wool was placed on his chest to prolong the agonies of death. However, the executioner – moved by the Rabbi’s proud and stoic stance amidst the fire – removed the wool and fanned the flame, thus accelerating the end, and then he himself plunged into the flames.[2]

According to Julius Caesar, the ancient Celts executed thieves and prisoners of war by burning them to death inside giant “wicker men”.[3] [4]

North American Indians often used burning as a form of execution, either against members of other tribes or against white settlers during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Roasting over a slow fire was a customary method.[5] See Captives in American Indian Wars.

Under the Byzantine Empire, burning was introduced as a punishment for disobedient Zoroastrians, because of the belief that they worshiped fire.[citation needed]

The Byzantine Emperor Justinian (r. 527–565) ordered death by fire, intestacy, and confiscation of all possessions by the State to be the punishment for heresy against the Christian faith in his Codex Iustiniani (CJ 1.5.), ratifying the decrees of his predecessors the Emperors Arcadius and Flavius Augustus Honorius.

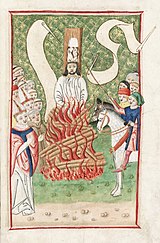

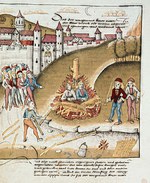

In 1184, the Roman Catholic Synod of Verona legislated that burning was to be the official punishment for heresy. It was also believed that the condemned would have no body to be resurrected in the Afterlife.[dubious – discuss] This decree was later reaffirmed by the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215, the Synod of Toulouse in 1229, and numerous spiritual and secular leaders through the 17th century.[citation needed]

Civil authorities burnt persons judged to be heretics under the medieval Inquisition, including Giordano Bruno. The historian Hernando del Pulgar, contemporary of Ferdinand and Isabella, estimated that the Spanish Inquisition had burned at the stake 2,000 people by 1490 (just one decade after the Inquisition began).[6] In the terms of the Spanish Inquisition a burning was described as relaxado en persona.

Burning was also used by Roman Catholics and Protestants during the witch-hunts of Europe. The penal code known as the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1532) decreed that sorcery throughout the Holy Roman Empire should be treated as a criminal offence, and if it purported to inflict injury upon any person the witch was to be burnt at the stake. In 1572, Augustus, Elector of Saxony imposed the penalty of burning for witchcraft of every kind, including simple fortunetelling.[7]

Among the best-known individuals to be executed by burning were Jacques de Molay (1314), Jan Hus (1415), St. Joan of Arc (30 May 1431), Savonarola (1498) Patrick Hamilton (1528), John Frith (1533), William Tyndale (1536), Michael Servetus (1553), Giordano Bruno (1600) and Avvakum (1682). Anglican martyrs Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley (both in 1555) and Thomas Cranmer (1556) were also burnt at the stake.

In Denmark the burning of witches increased following the reformation of 1536. Especially Christian IV of Denmark encouraged this practice, which eventually resulted in hundreds of people burnt because of convictions of witchcraft. This special interest of the king also resulted in the North Berwick witch trials with caused over seventy people to be accused of witchcraft in Scotland on account of bad weather when James VI of Scotland (later James I of England), who shared the Danish king’s interest in witch trials, in 1590 sailed to Denmark to meet his betrothed Anne of Denmark.

Edward Wightman, a Baptist from Burton on Trent, was the last person to be burnt at the stake for heresy in England in the market square of Lichfield, Staffordshire on 11 April 1612.

In the United Kingdom, the traditional punishment for women found guilty of treason was to be burnt at the stake, where they did not need to be publicly displayed naked, while men were hanged, drawn and quartered. There were two types of treason, high treason for crimes against the Sovereign, and petty treason for the murder of one’s lawful superior, including that of a husband by his wife.

In England, only a few accused of witchcraft were burnt; the majority were hanged. Sir Thomas Malory, in Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), depicts King Arthur as being reluctantly constrained to order the burning of Queen Guinevere, once her adultery with Lancelot was revealed, as a Queen’s adultery would be construed as treason against her royal husband.[8]

Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, first cousins and the second and fifth wives of Henry VIII were both condemned to be burnt alive or beheaded for adultery as the king’s pleasure should be known. Fortunately for Catherine and Anne, even Henry would not go so far. They were both beheaded. Lady Jane Grey the nine days queen was also condemned to burn as a traitress but it was commuted to beheading by Mary I.

In Massachusetts, there are two cases of burning at the stake. First, in 1681, a slave named Maria tried to kill her owner by setting his house on fire. She was convicted of arson and burned at the stake at Roxbury, Massachusetts.[9] Concurrently, a slave named Jack, convicted in a separate arson case, was hanged at a nearby gallows, and after death his body was thrown into the fire with that of Maria. Second, in 1755, a group of slaves had conspired and killed their owner, with servants Mark and Phillis executed for his murder. Mark was hanged and his body gibbeted, and Phillis burned at the stake, at Cambridge, Massachusetts.[10]

In New York, several burnings at the stake are recorded, particularly following suspected slave revolt plots. In 1708, one woman was burnt and one man hanged. In the aftermath of the New York Slave Revolt of 1712, 20 people were burnt, and during the alleged slave conspiracy of 1741, no less than 13 slaves were burnt at the stake.[11]

The last burning by the Spanish Colonial government in Latin America was of Mariana de Castro, in Lima in 1732.[12]

In 1790, Sir Benjamin Hammett introduced a bill into Parliament to end the practice. He explained that the year before, as Sheriff of London, he had been responsible for the burning of Catherine Murphy, found guilty of counterfeiting, but that he had allowed her to be hanged first. He pointed out that as the law stood, he himself could have been found guilty of a crime in not carrying out the lawful punishment and, as no woman had been burnt alive in the kingdom for over fifty years, so could all those still alive who had held an official position at all of the previous burnings. The Treason Act 1790 was duly passed by Parliament and given royal assent by King George III (30 George III. C. 48).[13][14]

Modern burnings

No modern state conducts executions by burning, apart from a mass execution in North Korea in the late 1990s.[15] Like all capital punishment, it is forbidden to members of the Council of Europe by the European Convention on Human Rights. It was never routinely practiced in the United States and in any case the Supreme Court while ruling on Firing Squads in Wilkerson v. Utah from 1879 incidentally determined that it was cruel and unusual punishment.

However, modern-day burnings still occur. In South Africa for example, extrajudicial execution by burning was done via a method called necklacing where rubber tires filled with kerosene (or gasoline) are placed around the neck of a live individual. The fuel is then ignited, the rubber melts, and the victim is burnt to death.[16][17] In Rio de Janeiro, burning people standing inside a pile of tires is a common form of murder used by drug dealers to punish those who have supposedly collaborated with the police. This form of burning is called microondas, “the microwave”. The movie Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad) has a scene depicting this practice.[18]

A former Soviet Main Intelligence Directorate officer writing under the alias Victor Suvorov, described in his book Aquarium a Soviet traitor being burnt alive in a crematorium.[19] There has been some speculation[20] that the identity of this officer was Oleg Penkovsky, however during his radio interview to Russian station Echo of Moscow Vladimir Rezun (alias Victor Suvorov) denied this, saying "I never mentioned it was Penkovsky" [21] No executed GRU traitors (Penkovsky aside) are known matching scant Suvorov's description given in "Aquarium"[22][23] (handsome manly face, worked in GRU in a rank of colonel).

During the 1980 New Mexico State Penitentiary riot, a number of inmates were burnt to death by fellow inmates, who used blow torches.

One of the most notorious extrajudicial burnings of modern times occurred in Waco, Texas in the USA on 15 May 1916. Jesse Washington, a mentally challenged African American farmhand, after having been convicted of the murder of a white woman, was taken by a mob to a bonfire, castrated, doused in coal oil, and hanged by the neck from a chain over the bonfire, slowly burning to death. A postcard from the event still exists, showing a crowd standing next to Washington’s charred corpse with the words on the back “This is the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe”. This event attracted international condemnation, and is remembered as the Waco Horror.

At the end of the 1990s, a number of North Korean army generals were executed by being burnt alive inside the Rungrado May Day Stadium in Pyongyang, North Korea.[15]

In 2002 Godhra Train Burning, a mob of 500 strong Muslims burnt a railway coach full of Hindu pilgrims.[24]

In Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, there were 400 cases of the burning of women in 2006. In Iraqi Kurdistan, at least 255 women had been killed in just the first six months of 2007, three-quarters of them by burning.[25]

It was reported on 21 May 2008, that in Kenya a mob had burnt to death at least 11 people accused of witchcraft.[26]

On 19 June 2008, the Taliban in Sadda, Lower Kurram, Pakistan burnt alive three truck drivers of the Turi tribe after attacking a convoy of trucks loaded with food and other basic needs and medicine on way from Kohat to Parachinar in the presence of security forces.[27]

Self-immolation by widows

Although sati, or the practice of a widow immolating herself on her husband’s funeral pyre, was officially outlawed by India’s British rulers in 1829, the rite persists. The most high-profile sati incident was in Rajasthan in 1987 when 18-year-old Roop Kanwar was burned to death.[28]

Bride-burning

Bride-burning is counted as a form of murder, not execution. On 20 January 2011, 28 year old Ranjeeta Sharma was found burning to death on a road in rural New Zealand. The New Zealand Police confirmed that the woman was alive before being covered in an accelerant and set alight.[29] Sharma’s husband, Davesh Sharma, was charged with her murder.[30]

Portrayal in film

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (The Passion of Joan of Arc), though made in the late 1920s (and therefore without the assistance of computer graphics), includes a relatively graphic and realistic treatment of Jeanne’s execution;[citation needed] his Day of Wrath also featured a woman burnt at the stake. Many other film versions of the story of Joan show her death at the stake – some more graphically than others. The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc, released in 1999, ends with Joan slowly burned alive in the marketplace of Rouen.

In Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), a mob attempts to execute a woman (actually a robot in the guise of a woman) by burning at the stake. The Seventh Seal (1957) shows a woman about to be burnt at the stake. In The Wicker Man (1973) a British Police Sergeant, after a series of tests to prove his suitability, is burnt to death by the local population inside a giant wicker cage in the shape of a man to assure the next year’s crops and simultaneously assuring his entering heaven as a martyr. In the film adaptation of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1986), the innocent simpleton Salvatore (Ron Perlman) is seen to die horribly, burnt at the stake. The fate is also suffered by Oliver Reed’s less innocent character Urbain Grandier in Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971). In 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992), several people are burnt at the stake.

The Last of the Mohicans (1992) features a British officer being burnt at the stake by a Huron tribe, though he is put out of his misery with a bullet fired by the protagonist before the flames could do further harm. In Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), an innocent gypsy woman Esmeralda is almost burnt at the stake, but rescued by Quasimodo. The nineteenth episode in the third season of The X Files contains a scene where a security officer discovers a man being burned alive in a crematory. The film Elizabeth (1998) used computer graphics to enhance the opening scene where three Protestants are burnt at the stake. In the 2005 horror sequel Saw II, a subject burns alive in a furnace while attempting to retrieve two antidotes to a gas that is slowly killing every person in the game. When he pulls the second syringe down from the ceiling of the furnace, he locks himself in and sets the fire alight at the same time.

In the 2007 film adaption and many of the musicals of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, Sweeney Todd throws Mrs. Lovett into an oven and watches her burn briefly before closing the door, as revenge for leading him to believe that his wife was dead. The horror film The Hills Have Eyes (2006) graphically portrays a man being burnt to death while tied to a tree. In the 2006 film Final Destination 3, two teenage girls become trapped in overheating tanning beds and are burnt to death when fires erupt. Silent Hill (2006) depicts death by burning as a punishment in two separate scenes. The Brazilian film Tropa de Elite (2007) depicts an execution by burning in Rio de Janeiro. In the film adaptation of Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons (2009), the third of four kidnapped cardinals is burned to death, after previously being branded with the ambigram “fire”; later in the film the main villain commits self-immolation in St Peter’s Basilica. The film Black Death (2010) includes scenes of death by fire associated with a knight of the military orders who is assigned to witch hunting. The movie-within-a-movie in Even the Rain shows Christopher Columbus's forces burning Taíno leader Hatuey at the stake for his resistance to the colonization of Hispaniola.

In Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, the people in a small Massachusetts town believe horror hostess Elvira (Cassandra Peterson) to be a witch and attempt to burn her at the stake.

In the 2011 film "Red Riding Hood", an autistic boy named Claude is burned to death in a Brazen Bull shaped like an elephant in an attempt to force him to reveal the identity of a werewolf.

See also

- Auto-da-fé

- Inquisition

- List of people burned as heretics

- Sati (practice) (widow-burning)

- Self-immolation

- Spanish Inquisition

- Spontaneous human combustion

- Witch-hunt

- Witchcraft

- Witchcraft Act

- Yaoya Oshichi

References

- ^ Freeman and Evans, History of Sicily, p. 76 and Appendix VII, citing Pindar, Polybius, and Diodorus.

- ^ Abodah Zarah 18a, Babylonian Talmud.

- ^ Caesar, Julius; Hammond, Carolyn (translator) (1998). The Gallic War. The Gallic War, p. 128. ISBN 0-19-283582-3.

- ^ Caesar, Gallic War 6.16, English translation by W. A. McDevitte and W. S. Bohn (1869); Latin text edition, from the Perseus Project.

- ^ Scott, G (1940) “A History of Torture”, p. 41.

- ^ Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision., p.62, (Yale University Press, 1997).

- ^ Thurston, H. (1912). Witchcraft. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 12 December 2010 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15674a.htm

- ^ Robert L. Kelly (1995). "Malory and the Common Law". In Paul Maurice Clogan (ed.). Studies in medieval and Renaissance culture: diversity. Medievalia et humanistica. Vol. 22. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 111–140. ISBN 0-8476-8099-1.

- ^ Maria, Burned at the Stake at CelebrateBoston.com

- ^ Mark and Phillis Executions at CelebrateBoston.com

- ^ Edwin Hoey, "Terror in New York – 1741", American Heritage, June 1974, Retrieved 9 July 2010

- ^ René Millar Carvacho La Inquisición de Lima: signos de su decadencia, 1726–1750 2004 p62 “.. y que habiendo llegado el caso de practicar lo determinado por el Consejo en auto de 4 de febrero de 1732, ... acordaron, después de revisar la causa de Mariana de Castro y lo determinado por la Suprema el 4 de febrero de 1732, ”

- ^ Burning at the stake.

- ^ James Holbert Wilson (1853). Temple bar, the city Golgotha, by a member of the Inner Temple. p. 4.

- ^ a b Soukhorukov, Sergey (13 June 2004). "Train blast was 'a plot to kill North Korea's leader'". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ U.S. Sanctions against South Africa, 1986, College of Arts and Sciences, East Tennessee State University. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ Hilton, Ronald. "Latin America," World Association of International Studies, Stanford University. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ Ronaldo França. "Como na Chicago de Capone". Veja on-line (30 January 2002). Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ^ Suworow, Viktor. GRU – Die Speerspitze: Was der KGB für die Polit-Führung, ist die GRU für die Rote Armee. 3., korr. Aufl. Solingen: Barett, 1995. ISBN 3-924753-18-0. Template:De icon

- ^ http://www.tnr.com/article/politics/the-newer-meaning-treason

- ^ http://www.echo.msk.ru/programs/hrushev/655886-echo/

- ^ http://lib.ru/WSUWOROW/akwarium.txt

- ^ http://www.scribd.com/doc/46398733/Suvorov-Aquarium-The-Career-and-Defection-of-a-Soviet-Spy-1985

- ^ http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-03-01/india/28643060_1_haji-billa-godhra-train-rajjak-kurkur

- ^ Mark Lattimer on the brutal treatment of women in Iraq, The Guardian, 13 December 2007.

- ^ Mob burns to death 11 Kenyan "witches".

- ^ Article: (8 slaughtered, three burnt alive in Kurram Agency).

- ^ "The New York Times, 1987". 20 September 1987. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- ^ Feek, Belinda (24 January 2011). "Burnt body victim named as search goes offshore". Waikato Times. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Husband of burnt woman charged with murder". The New Zealand Herald. 29 January 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

External links