Rape during the occupation of Germany: Difference between revisions

→Analysis: new text |

|||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

With respect to the number of abortions reported in Berlin, and the estimates of number of rapes based on the abortions statistics, there are some alternative contentions which don't necessarily involve rapes by Soviet soldiers. Atina Grossman in her article in "October"<ref>[http://www.jstor.org/pss/778926 JSTOR: October, Vol. 72 (Spring, 1995), pp. 42–63]</ref> describes how until early 1945 the abortions in Germany were illegal (except for medical and eugenic reasons), and so when doctors opened up and started performing abortions to rape victims (for which only an affidavit was requested from a woman), many women would claim they were raped but their accounts were surprisingly uniform (describing rapists as having "mongoloid or asiatic type"). It was also typical that women specified their reasons for abortions being mostly socio-economic (inability to raise another child) rather than moral or ethical.{{citation needed|date=January 2014}} |

With respect to the number of abortions reported in Berlin, and the estimates of number of rapes based on the abortions statistics, there are some alternative contentions which don't necessarily involve rapes by Soviet soldiers. Atina Grossman in her article in "October"<ref>[http://www.jstor.org/pss/778926 JSTOR: October, Vol. 72 (Spring, 1995), pp. 42–63]</ref> describes how until early 1945 the abortions in Germany were illegal (except for medical and eugenic reasons), and so when doctors opened up and started performing abortions to rape victims (for which only an affidavit was requested from a woman), many women would claim they were raped but their accounts were surprisingly uniform (describing rapists as having "mongoloid or asiatic type"). It was also typical that women specified their reasons for abortions being mostly socio-economic (inability to raise another child) rather than moral or ethical.{{citation needed|date=January 2014}} |

||

Yelena Senyavskaya criticizes Beevor for using and popularizing the "accurate statistic" that 2 million German women were raped by the Soviet Army. The calculation used to derive this number is based on the number of newborns in 1945 and 1946 whose fathers are listed as Russian in one Berlin clinic (an assumption was made that all of these births were the result of rape), and the extrapolation of this data on the entire female population (ages 8 to 80) of the eastern part of Germany. Such method of calculation does not hold up to any criticism according to Senyavskaya. She further argues that the fact that Beevor uses Soviet archival documents does not prove anything. There are large concentrations of reports and tribunal materials about crimes committed by army personnel, but that is because such documents were stored together thematically. Occurrences of crimes by Soviet servicemen were considered extraordinary rather than the norm. Senyavskaya points out that "those guilty of these crimes account for no more than two percent of the total number of servicemen. However, authors like Beevor spread their accusations against the entire Soviet Army."<ref name=Senyavskaya/> |

|||

The statistics used by Beevor are also questioned by Nicky Bird: "Perhaps 2 million German women were raped, 100,000 in greater Berlin. Beevor estimates that 10,000 died, some murdered, most from suicide. The mortality rates for the 1.4 million raped in East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia were probably much higher. Statistics proliferate, and are unverifiable. Beevor tends to accept estimates from a single doctor — how can we possibly know that 90 percent of Berlin women were infected by VD, that 90 percent of rape victims had abortions, that 8.7 percent of children born in 1946 had Russian fathers?"<ref name=Bird>{{cite journal |last=Bird |first=Nicky |title=Berlin: The Downfall 1945 by Antony Beevor |journal=International Affairs |volume=78 |number=4 |date=October 2002 |pages=914-916 |institution=Royal Institute of International Affairs}}</ref> |

|||

===Social effects=== |

===Social effects=== |

||

Revision as of 17:42, 3 June 2014

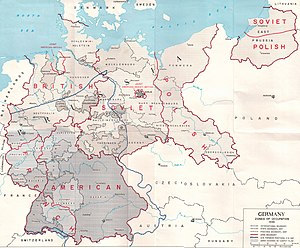

As Allied troops entered and occupied German territory during the later stages of World War II, mass rapes took place, both in connection with combat operations and during the subsequent occupation that was to last many years. The most numerous according to Western scholarly consensus are the rapes committed by Soviet servicemen, for which estimates range from tens of thousands to two million. While agreeing that such crimes occurred, prominent Russian historians have criticized the estimates given and argue that these crimes were not widespread.

Soviet Military

A wave of rapes and sexual violence occurred in Central Europe in 1944–45, as the Western Allies and the Red Army fought their way into the Third Reich.[1] On the territory of the Nazi Germany, it began on 21 October 1944 when troops of the Red Army crossed the bridge over the Angerapp creek (marking the border) and committed the Nemmersdorf massacre before they were beaten back a few hours later.

The majority of the assaults were committed in the Soviet occupation zone; estimates of the numbers of German women raped by Soviet soldiers range from the tens of thousands to 2 million.[2][3][4][5][6] In many cases women were the victims of repeated rapes, some as many as 60 to 70 times.[7] At least 100,000 women are believed to have been raped in Berlin, based on surging abortion rates in the following months and contemporary hospital reports,[4] with an estimated 10,000 women dying in the aftermath.[8] Female deaths in connection with the rapes in Germany, overall, are estimated at 240,000.[9][10] Antony Beevor describes it as the "greatest phenomenon of mass rape in history", and has concluded that at least 1.4 million women were raped in East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia alone.[11]

Natalya Gesse states that Russian soldiers raped German females from eight to eighty years old. Russian women were not spared either.[12][13][14] In contrast, a Russian war veteran Vsevolod Olimpiev recalled, "The Soviet soldiers' relations with the German population where it had stayed may be called indifferent and neutral. Nobody, at least from our Regiment, harassed or touched them. Moreover, when we came across an obviously starving German family with kids we would share our food with them with no unnecessary words."[15]

Stalin reportedly stated that people should 'understand it if a soldier who has crossed thousands of kilometres through blood and fire and death has fun with a woman or takes some trifle'.[16] On another occasion, when told that Red Army soldiers sexually maltreated German refugees, he said: 'We lecture our soldiers too much; let them have their initiative.'[17]

An order issued on January 19, 1945 and signed by Stalin said,

Officers and men of the Red Army! We are entering the country of the enemy... the remaining population in the liberated areas, regardless of whether they're German, Czech, or Polish, should not be subjected to violence. The perpetrators will be punished according to the laws of war. In the liberated territories, sexual relations with females are not allowed. Pepetrators of violence and rape will be shot.[18]

After the summer of 1945, Soviet soldiers caught raping civilians were usually punished to some degree, ranging from arrest to execution.[19] The rapes continued, however, until the winter of 1947–48, when Soviet occupation authorities finally confined Soviet troops to strictly guarded posts and camps,[20] separating them from the residential population in the Soviet zone of Germany.

Controversy in Russia

There is dispute in Russia concerning these claims.[21] They have encountered vast criticism from historians in Russia and the Russian government.[22] Critics argue that the numbers given are based on faulty methodology and questionable sources. They argue that although there were cases of excesses and heavy-handed command, the Red Army as a whole treated the population of the former Reich with respect. In his review of Berlin: The Downfall 1945, O.A. Rzheshevsky, a professor and President of the Russian Association of World War II Historians, has charged that Beevor is merely resurrecting the discredited and racist views of Neo-Nazi historians, who depicted Soviet troops as subhuman "Asiatic hordes."[23] In an interview with BBC News Online, Rzheshevsky admitted that he had only read excerpts and had not seen the book's source notes. He claimed that Beevor's use of phrases such as "Berliners remember" and "the experiences of the raped German women" were better suited "for pulp fiction, than scientific research." Rzheshevsky further stated that the Germans could have expected an "avalanche of revenge," but that did not happen.[21]

According to Rzheshevsky 4,148 Red Army officers and many enlisted men were "punished" for atrocities.[21] Rzheshevsky states that acts such as robbery and sexual assault are inevitable parts of war, and men of Soviet and other Allied armies committed them. But in general, he contends, the Soviet soldiers treated peaceful Germans with humanity.[24]

Colonel Ivan Busik, Director of Russia's Institute of Military History, wrote that Hero of the Soviet Union Army General Ivan Tretiak told him that there was not a single case of violence committed by men in his regiment. Tretiak said that although he wanted revenge, Stalin's orders on treating the population humanely were implemented, and discipline in the army strengthened. Tretiak said that in such a huge military group as that in Germany, there was bound to be cases of sexual misconduct, as men had not seen women in years. However, he explains that sexual relations were not always violent, but often involved mutual consent. The work of Beevor and others alleging mass rape is characterized by Tretiak as "filthy cynicism, because the vast majority of those who have been slandered cannot reply to these liars."[25]

Makhmud Gareyev, President of the Academy of Military Sciences, who participated in the East Prussia campaign, said that he had not heard about sexual violence at all. He stated that after what the Nazis did to Russia, excesses were likely to take place, but that such cases were strongly suppressed and punished, and were not widespread. He notes that the Soviet military leadership on 19 January 1945 signed an executive order calling on the avoidance of a rough relationship with the local population. Gareyev said that Beevor copied Goebbels' propaganda about the "aggressive sexuality of our soldiers."[26]

Russian historian[27][28] Aleksandr Dyukov wrote, "the Germans did not experience a fraction of the horror that their soldiers staged in the East. Despite some excesses, which were firmly suppressed by the Command, the Red Army as a whole behaved toward the people of the Reich with humanity". The Russian soldiers are credited with feeding the German population, rescuing children, and helping to restore normal life in the country.[29]

According to Doctor of Historical Sciences Yelena Senyavskaya: "One of the most widespread anti-Russian myths in the West today is the subject of mass rapes allegedly committed by the Red Army in 1945 in Europe. Its beginning goes back to the end of the war – from Goebbels' propaganda, and then from publications of the former allies in the anti-Hitler coalition, who soon turned into opponents of the USSR in the Cold War."[30]

Analysis

In his analysis of the motives behind the extensive Soviet rapes, Norman Naimark singles out "hate propaganda, personal experiences of suffering at home, and a fully demeaning picture of German women in the press, not to mention among the soldiers themselves" as a part reason for the widespread rapes.[31] Naimark also noted the effect that the Russian tendency to binge-drink alcohol (of which much was available in Germany) had on the propensity of Russian soldiers to commit rape, especially rape-murder.[32] Naimark also notes the patriarchal nature of Russian culture, and of the Asian societies comprising the Soviet Union, where dishonor was in the past repaid by raping the women of the enemy.[33] The fact that the Germans had a much higher standard of living (with things such as indoor toilets), visible even when in ruins "may well have contributed to a national inferiority complex among Russians". Combining Russian feelings of inferiority and the resulting need to restore his honor and their desire for revenge may be the reason many women were raped in public as well as in front of husbands before both were killed.[33]

According to Antony Beevor revenge played very little role in the frequent rapes; according to him the main reason for the rapes was the Soviet troops' feeling of entitlement to all types of booty, including women. Beevor exemplifies this with his discovery that Soviet troops also raped Russian and Polish girls and women that were liberated from Nazi concentration camps.[34]

Richard Overy, a historian from King's College London, has criticized the viewpoint held by the Russians, asserting that they refuse to acknowledge Soviet war crimes committed during the war, "Partly this is because they felt that much of it was justified vengeance against an enemy who committed much worse, and partly it was because they were writing the victors' history."[21]

According to Alexander Statiev, while Soviet soldiers respected their own citizens and those of friendly countries, they perceived themselves to be conquerors rather than liberators in hostile regions. They viewed violence against civilians as a privilege of victors. Statiev cites the attitude of a Soviet soldier as exemplifying this phenomenon:

Avenge! You are a soldier-avenger! … Kill the German, and then jump the German woman! This is how a soldier celebrates victory![35]

With respect to the number of abortions reported in Berlin, and the estimates of number of rapes based on the abortions statistics, there are some alternative contentions which don't necessarily involve rapes by Soviet soldiers. Atina Grossman in her article in "October"[36] describes how until early 1945 the abortions in Germany were illegal (except for medical and eugenic reasons), and so when doctors opened up and started performing abortions to rape victims (for which only an affidavit was requested from a woman), many women would claim they were raped but their accounts were surprisingly uniform (describing rapists as having "mongoloid or asiatic type"). It was also typical that women specified their reasons for abortions being mostly socio-economic (inability to raise another child) rather than moral or ethical.[citation needed]

Yelena Senyavskaya criticizes Beevor for using and popularizing the "accurate statistic" that 2 million German women were raped by the Soviet Army. The calculation used to derive this number is based on the number of newborns in 1945 and 1946 whose fathers are listed as Russian in one Berlin clinic (an assumption was made that all of these births were the result of rape), and the extrapolation of this data on the entire female population (ages 8 to 80) of the eastern part of Germany. Such method of calculation does not hold up to any criticism according to Senyavskaya. She further argues that the fact that Beevor uses Soviet archival documents does not prove anything. There are large concentrations of reports and tribunal materials about crimes committed by army personnel, but that is because such documents were stored together thematically. Occurrences of crimes by Soviet servicemen were considered extraordinary rather than the norm. Senyavskaya points out that "those guilty of these crimes account for no more than two percent of the total number of servicemen. However, authors like Beevor spread their accusations against the entire Soviet Army."[30]

The statistics used by Beevor are also questioned by Nicky Bird: "Perhaps 2 million German women were raped, 100,000 in greater Berlin. Beevor estimates that 10,000 died, some murdered, most from suicide. The mortality rates for the 1.4 million raped in East Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia were probably much higher. Statistics proliferate, and are unverifiable. Beevor tends to accept estimates from a single doctor — how can we possibly know that 90 percent of Berlin women were infected by VD, that 90 percent of rape victims had abortions, that 8.7 percent of children born in 1946 had Russian fathers?"[37]

Social effects

A number of "Russian babies" were born during the occupation, many of them as the result of rape.[38]

According to Norman Naimark we may never know how many German women and girls were raped by Soviet troops during the war and occupation, their numbers are likely in the hundreds of thousands, and possibly as many as 2 million.[39] As to the social effects of this sexual violence Naimark notes:

- In any case, just as each rape survivor carried the effects of the crime with her till the end of her life, so was the collective anguish nearly unbearable. The social psychology of women and men in the soviet zone of occupation was marked by the crime of rape from the first days of occupation, through the founding of the GDR in the fall of 1949, until—one could argue—the present.[39]

West Berliners and women of the wartime generation refer to the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park, Berlin, as the "tomb of the unknown rapist" in response to the mass rapes by Red Army soldiers in the years following 1945.[40][41][need quotation to verify][42][need quotation to verify][43][need quotation to verify][44][need quotation to verify][45]

Soviet literature

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn took part in the invasion of Germany, and wrote a poem about it: Prussian Nights; "Twenty-two Hoeringstrasse. It's not been burned, just looted, rifled. A moaning by the walls, half muffled: the mother's wounded, half alive. The little daughter's on the mattress, dead. How many have been on it? A platoon, a company perhaps? A girl's been turned into a woman, a woman turned into a corpse. . . . The mother begs, "Soldier, kill me!"[46]

Svetlana Alexievich published a book, War's Unwomanly Face that includes memories by Soviet veterans about their experience in Germany. According to a former army officer,

We were young, strong, and four years without women. So we tried to catch German women and ... Ten men raped one girl. There were not enough women; the entire population run from the Soviet Army. So we had to take young, twelve or thirteen year-old. If she cried, we put something into her mouth. We thought it was fun. Now I can not understand how I did it. A boy from a good family... But that was me.[47]

A woman telephone operator from the Soviet Army recalled that

When we occupied every town, we had first three days for looting and ... [rapes]. That was unofficial of course. But after three days one could be court-martialed for doing this. ... I remember one raped German woman laying naked, with hand grenade between her legs. Now I feel shame, but I did not feel shame back then... Do you think it was easy to forgive [the Germans]? We hated to see their clean undamaged white houses. With roses. I wanted them to suffer. I wanted to see their tears. ... Decades had to pass until I started feeling pity for them.[48]

In popular culture

As most women recoiled from their experiences and had no desire to recount them, most biographies and depictions of the period, like the German film Downfall, alluded to mass rape by the Red Army but stopped shy of mentioning it explicitly. As time has progressed more works have been produced that have directly addressed the issue, such as the books The 158-Pound Marriage and My Story (1961) by Gemma LaGuardia Gluck [reissued as Fiorello's Sister: Gemma La Guardia Gluck's Story (Religion, Theology, and the Holocaust) (2007, Expanded Edition)],[49][50] or the 2006 films Joy Division and The Good German.

The topic is the subject of much feminist discourse.[51] The first autobiographical work depicting the events was the groundbreaking 1954 book A Woman in Berlin, which was made into a 2008 feature film. It was widely rejected in Germany after its initial publication but has seen a new acceptance and many women have found inspiration to come forward with their own stories.[52][53][54]

US Military

In Taken by Force, J. Robert Lilly estimates the number of rapes committed by U.S. servicemen in Germany to be 11,040.[55] As in the case of the American occupation of France after the D-Day invasion, many of the American rapes in Germany in 1945 were gang rapes committed by armed soldiers at gunpoint.[56]

Although non-fraternization policies were instituted for the Americans in Germany, the phrase "copulation without conversation is not fraternization" was used as a motto by United States Army troops.[57] The journalist Osmar White, a war correspondent from Australia who served with the American troops during the war, wrote that

After the fighting moved on to German soil, there was a good deal of rape by combat troops and those immediately following them. The incidence varied between unit and unit according to the attitude of the commanding officer. In some cases offenders were identified, tried by court martial, and punished. The army legal branch was reticent, but admitted that for brutal or perverted sexual offences against German women, some soldiers had been shot – particularly if they happened to be Negroes. Yet I know for a fact that many women were raped by white Americans. No action was taken against the culprits. In one sector a report went round that a certain very distinguished army commander made the wisecrack, 'Copulation without conversation does not constitute fraternisation.'[58]

A typical victimization with sexual assault by drunken American personnel marching through occupied territory involved threatening a German family with weapons, forcing one or more women to engage in sex, and putting the entire family out on the street afterward.[57]

As in the eastern sector of the occupation, the number of rapes peaked in 1945, but a high rate of violence against the German and Austrian populations by the Americans lasted at least into the first half of 1946, with five cases of dead German women found in American barracks in May and June 1946 alone.[56]

Carol Huntington writes that the American soldiers who raped German women and then left gifts of food for them may have permitted themselves to view the act as a prostitution rather than rape. Citing the work of a Japanese historian alongside this suggestion, Huntington writes that Japanese women who begged for food "were raped and soldiers sometimes left food for those they raped."[56]

The black soldiers of America's segregated occupation force were both more likely to be charged with rape and severely punished.[56] Heide Fehrenbach writes that, while the American black soldiers were in fact by no means free from indiscipline,

The point, rather, is that American officials exhibited an explicit interest in a soldier's race, and then only if he were black, when reporting behavior they feared would undermine either the status or the political aims of the U.S. Military Government in Germany.[59]

British and Canadian troops

Although far from the scale of those committed by the Red Army, rape of local women and girls by British and Canadian troops was a regular occurrence during the last months of WWII in Germany. Even elderly women were targeted. Though a high-profile issue for the Royal Military Police, some officers did not treat the behaviour of their men seriously. Many rapes were committed under the effects of alcohol or post-traumatic stress, but some cases of premeditated attacks, like the attempted rape of two local girls at gunpoint by two soldiers in the village of Oyle, near Nienburg, which ended in the death of one of the women when, whether intentionally or not, one of the soldiers discharged his gun, hitting her in the neck, as well as the reported assault on three German women in the town of Neustadt am Rübenberge.[60] On a single day in mid-April 1945, three women in Neustadt were raped by British soldiers. A senior British Army chaplain following the troops reported that there was a 'good deal of rape going on'. He then added that "those who suffer [rape] have probably deserved it.'[61]

French Military

French troops took part in the invasion of Germany, and France was assigned an occupation zone in Germany. According to Perry Biddiscombe the French for instance committed "385 rapes in the Constance area; 600 in Bruchsal; and 500 in Freudenstadt."[62] The soldiers of France indulged in an orgy of rape in the Höfingen District near Leonberg.[63]

According to Norman Naimark, French Moroccan troops matched the behavior of Soviet troops when it came to rape, in particular in the early occupation of Baden and Württemberg.[64]

Discourse

In postwar Germany, especially in West Germany, the war time rape stories became an essential part of political discourse.[2] The rape of German women (along with the expulsion of Germans from the East and Allied occupation) had been universalized in an attempt to situate the German population on the whole as victims.[2] This discourse became wholly discredited by the late 1960s; since the 1970s on German leftists conducted politics focused on critical investigation of the Nazi past, the older generations' unwillingness to face that past, and their tendency to portray themselves as victims rather than as perpetrators, particularly of the Holocaust.[65] Therefore, the frequently reiterated claim that the war time rapes had been surrounded by decades of silence[9][66] is probably not correct.[65]

The way the rapes have been discussed by Sander and Johr in their "BeFreier und Befreite"[9] has been criticized by several scholars. According to Grossmann, the problem is that this is not a "universal" story of women being raped by men, but of German women being abused and violated by an army that fought Nazi Germany and liberated death camps.[8] Such attempts to de-emphasize the historical context of the rape of German women is a serious omission, according to Stuart Liebman and Annette Michelson,[67] and, according to Pascale Bos, is an example of ahistorical, feminist and sexist approach to the wartime rape issue.[65]

According to Pascale Bos, the feminist attempt to universalize the story of the rapes of German women came into a contradiction with Sander's and Johr's own description of the rapes as a form of genocidal rape: the rape of "racially superior" German women by "racially inferior" Soviet soldiers, implying that such a rape was especially harmful for the victims.[65] In contrast, the issue of the rapes of Soviet women by Wehrmacht soldiers, that, according to some estimation amounted hundreds of thousands, and possibly millions[68][69] is not treated by the authors as something deserving serious mention.[65]

See also

- War rape

- Rape during the occupation of Japan

- Rape during the liberation of Poland

- U.N. Comfort Station

- Special Comfort Facility Association

- Comfort women

- Marocchinate rape after the Battle of Monte Cassino

- Soviet war crimes

- War crimes of the Wehrmacht: Mass rapes

- German camp brothels in World War II

- Rape during the liberation of France

Further reading

- Naimark, Norman M. (1995). The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-78405-7.

- Alexievich, Svetlana (1988). War's Unwomanly Face. Moscow: Progress publishers. ISBN 978-5010004941. (Translated from original edition in Russian: Алексиевич, Светлана (2008). У войны не женское лицо (in Russian). Moscow: Vremya publishers. ISBN 978-5-9691-0331-3.) Note: citations in text are given in reference to the Russian edition.

References

- ^ Biddiscombe, Perry (2001). "Dangerous Liaisons: The Anti-Fraternization Movement in the U.S. Occupation Zones of Germany and Austria, 1945–1948". Journal of Social History. 34 (3): 611–647. doi:10.1353/jsh.2001.0002. JSTOR 3789820.

- ^ a b c Heineman, Elizabeth (1996). "The Hour of the Woman: Memories of Germany's "Crisis Years" and West German National Identity". American Historical Review. 101 (2): 354–395. JSTOR 2170395.

- ^ Kuwert, P.; Freyberger, H. (2007). "The unspoken secret: Sexual violence in World War II". International Psychogeriatrics. 19 (4): 782–784. doi:10.1017/S1041610207005376.

- ^ a b http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/berlin_01.shtml

- ^ Hanna Schissler The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949–1968 [1]

- ^ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=106687768

- ^ William I. Hitchcock The Struggle for Europe The Turbulent History of a Divided Continent 1945 to the Present ISBN 978-0-385-49799-2

- ^ a b Atina Grossmann. A Question of Silence: The Rape of German Women by Occupation Soldiers October, Vol. 72, Berlin 1945: War and Rape "Liberators Take Liberties" (Spring, 1995), pp. 42–63 MIT Press. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778926

- ^ a b c Helke Sander/Barbara Johr: BeFreier und Befreite, Fischer, Frankfurt 2005

- ^ Seidler/Zayas: Kriegsverbrechen in Europa und im Nahen Osten im 20. Jahrhundert, Mittler, Hamburg Berlin Bonn 2002

- ^ Sheehan, Paul (17 May 2003). "An orgy of denial in Hitler's bunker". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (1 May 2002). "They raped every German female from eight to 80". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Fall of Berlin 1945. [citation needed]

- ^ Richard Bessel, Germany 1945. [citation needed]

- ^ On the Bloody Road to Berlin: Frontline Accounts from North-West Europe & the Eastern Front, 1944-45 By Duncan Rogers and Sarah Williams

- ^ http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Joseph_Stalin

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (24 October 2008). "Stalin's army of rapists: The brutal war crime that Russia and Germany tried to ignore". Daily Mail. London.

- ^ http://statehistory.ru/32/Mif-o-millionakh-iznasilovannykh-nemok/

- ^ Naimark, p. 92

- ^ Naimark, p. 79

- ^ a b c d Summers, Chris (29 April 2002). "Red Army rapists exposed". BBC News Online. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Daniel (25 January 2002). "Russians angry at war rape claims". The Daily Telegraph. United Kingdom. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Review of Berlin: 1945 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Секс-Освобождение: эротические мифы Второй мировой

- ^ http://svpressa.ru/war/article/8271/

- ^ Erotic Myths of the Second World War

- ^ http://rt.com/news/khalkhin-gol-battle-anniversary/

- ^ http://rt.com/programs/spotlight/estonia-genocide-that-never-was/

- ^ http://militera.lib.ru/research/dukov_ar/24.html

- ^ a b Senyavskaya, Yelena, "Красная Армия в Европе в 1945 году в контексте информационной войны", histrf.ru, Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation, retrieved 1 June 2014

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Naimark, pp. 108–109

- ^ Naimark, p. 112

- ^ a b Naimark, pp. 114–115

- ^ [2] Red Army troops raped even Russian women as they freed them from camps, 24 Jan 2002, The Telegraph

- ^ Statiev, Alexander (2010). The Soviet Counterinsurgency in the Western Borderlands. Cambridge University Press. p. 277.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ JSTOR: October, Vol. 72 (Spring, 1995), pp. 42–63

- ^ Bird, Nicky (October 2002). "Berlin: The Downfall 1945 by Antony Beevor". International Affairs. 78 (4). Royal Institute of International Affairs: 914–916.

- ^ http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/0,1518,500251,00.html

- ^ a b Naimark, pp. 132–133

- ^ Johnson, Daniel (25 January 2002). "Red Army troops raped even Russian women as they freed them from camps". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ Antony Beevor, Berlin – The Downfall 1945

- ^ Ksenija Bilbija, Jo Ellen Fair, Cynthia E., The art of truth-telling about authoritarian rule, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2005, p70

- ^ Allan Cochrane, Making Up Meanings in a Capital City: Power, Memory and Monuments in Berlin, European Urban and Regional Studies, Vol. 13, No. 1, 5–24 (2006)

- ^ J.M. Dennis, Rise and Fall of the German Democratic Republic 1945–1990, p.9, Longman, ISBN 0-582-24562-1

- ^ Jerry Kelly (2006). In the Grip of the Iron Curtain. p. 118. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Prussian Nights: A Poem [Prusskie nochi], Robert Conquest, trans. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977).

- ^ Alexievich, p. 33

- ^ Alexievich, p. 386

- ^ Rememberwomen.org http://www.rememberwomen.org/Library/BkReviews/main.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Fiorello's Sister: Gemma LaGuardia Gluck's Story (Religion, Theology, and the Holocaust). Syracuse University Press. 2007, originally published as My Story in 1961.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ http://dir.salon.com/story/books/review/2005/08/18/berlin/index.html

- ^ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=106557039

- ^ "German women break their silence on the rape of Berlin". The Age. Melbourne. 25 October 2008.

- ^ Hegi, Ursula (4 September 2005). "After the Fall". The Washington Post.

- ^ Taken by Force: Rape and American GIs in Europe during World War II. J Robert Lilly. ISBN 978-0-230-50647-3 p.12

- ^ a b c d Harrington, Carol (2010). Politicization of Sexual Violence: From Abolitionism to Peacekeeping. London: Ashgate. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-7546-7458-4.

- ^ a b Schrijvers, Peter (1998). The Crash of Ruin: American Combat Soldiers in Europe During World War II. New York: New York University Press. p. 183. ISBN 0-8147-8089-X.

- ^ White, Osmar (1996). Conquerors' Road: An Eyewitness Report of Germany 1945. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-521-83051-6.

- ^ Fehrenbach, Heide (2005). Race After Hitler: Black Occupation Children in Postwar Germany and America. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-691-11906-9.

- ^ Longden, Sean. To the victor the spoils: D-Day to VE Day, the reality behind the heroism. Arris Books. p. 276. ISBN 9781844370382.

- ^ Emsley, Clive (2013) Soldier, Sailor, Beggarman, Thief: Crime and the British Armed Services since 1914. Oxford University Press, USA, p. 128-129; ISBN 0199653712

- ^ Biddiscombe, Perry (2001). "Dangerous Liaisons: The Anti-Fraternization Movement in the U.S. Occupation Zones of Germany and Austria, 1945–1948". Journal of Social History. 34 (3): 635. doi:10.1353/jsh.2001.0002. JSTOR 3789820.

- ^ Stephenson, Jill (2006). Hitler's Home Front: Württemberg under the Nazis London: Continuum. p. 289. ISBN 1-85285-442-1.

- ^ Naimark, pp. 106–107

- ^ a b c d e Pascale R . Bos, Feminists Interpreting the Politics of Wartime Rape: Berlin, 1945; Yugoslavia, 1992–1993 Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2006, vol. 31, no. 4, p.996-1025

- ^ [3][4]See also

- ^ Stuart Liebman and Annette Michelson. After the Fall: Women in the House of the Hangmen, October, Vol. 72, (Spring, 1995) pp. 4–14

- ^ Gertjejanssen, Wendy Jo. 2004. "Victims, Heroes, Survivors: Sexual Violence on the Eastern Front during World War II." PhD diss., University of Minnesota.

- ^ A 1942 Wehrmacht document suggested that the Nazi leadership considered implementing a special policy for the eastern front through which the estimated 750,000 babies born through sexual contact between the German soldiers and Russian women (an estimate deemed very conservative) could be identified and reclaimed as racially German. (The suggestion was made to add the middle names Friedrich and Luise to the birth certificates for boy and girl babies, respectively.) Although the plan was not implemented, such documents suggest that the births that resulted from rapes and other forms of sexual contact were deemed as beneficial, as increasing the "Aryan" race rather than as adding to the inferior Slavic race. The underlying ideology suggests that German rape and other forms of sexual contact may need to be seen as conforming to a larger military strategy of racial and territorial dominance. (Pascale R. Bos, Feminists Interpreting the Politics of Wartime Rape: Berlin, 1945; Yugoslavia, 1992–1993 Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2006, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 996–1025)

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (January 2010) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|