Ninjutsu: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by SoTotallyRealScientist (talk): unexplained content removal (HG) |

|||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

While there are [[Modern Schools of Ninjutsu|several styles of modern ninjutsu]], the historical lineage of these styles is disputed. Some schools and masters claim to be the only legitimate heir of the art, but ninjutsu is not centralized like modernized martial arts such as [[judo]] or [[karate]]. [[Togakure-ryū]] claims to be the oldest recorded form of ninjutsu, and claims to have survived past the 1500s.<ref>[[Togakure-ryū]]</ref> |

While there are [[Modern Schools of Ninjutsu|several styles of modern ninjutsu]], the historical lineage of these styles is disputed. Some schools and masters claim to be the only legitimate heir of the art, but ninjutsu is not centralized like modernized martial arts such as [[judo]] or [[karate]]. [[Togakure-ryū]] claims to be the oldest recorded form of ninjutsu, and claims to have survived past the 1500s.<ref>[[Togakure-ryū]]</ref> |

||

==History== |

|||

http://www.reddit.com/r/PhotoshopRequest/ |

|||

{{Main|Ninja}} |

|||

Spying in Japan dates as far back as [[Prince Shōtoku]] (572–622), although the origins of the Ninja date much earlier.<ref>Szczepanski, Kallie. [http://www.asianhistory.about.com/od/warsinasia/p/NinjaProfile.htm "History of the Ninja"], [[About.com]], accessed June 2, 2011.</ref> According to [[Shōninki]], the first open usage of ninjutsu during a military campaign was in the Gempei War, when Minamoto no Kuro Yoshitsune chose warriors to serve as shinobi during a battle; this manuscript goes on to say that, during the Kenmu era, Kusonoki Masashige used ninjutsu frequently. According to footnotes in this manuscript, the Gempei war lasted from 1180 to 1185, and the Kenmu Restoration occurred between 1333 and 1336.<ref>Masazumi, Natori, translated by Editions Albin Michel and Jon E. Graham. "Shoninki: the Secret Teachings of the Ninja; the 17th-Century Manual on the Art of Concealment", English Translation Copyright 2010 by Inner Trditions International.</ref> Ninjutsu was developed by groups of people mainly from the [[Iga Province]] and [[Kōka, Shiga]] of Japan.{{Citation needed|date=May 2011}} Throughout history the ''shinobi'' have been seen as [[assassination|assassin]]s, scouts and spies who were hired mostly by territorial lords known as the [[Daimyo]]. They conducted operations that the samurai were forbidden to partake in.<ref>[http://michigan-ninjutsu.com Shinobi-Do Ninjutsu]</ref> They are mainly noted for their use of stealth and deception. Throughout history many different schools (''[[ryū (school)|ryū]]'') have taught their unique versions of ninjutsu. An example of these is the [[Togakure-ryū]]. This ryū was developed after a defeated samurai warrior called Daisuke Togakure escaped to the region of Iga. Later he came in contact with the warrior-monk Kain Doshi who taught him a new way of viewing life and the means of survival (ninjutsu).<ref>Hayes, Stephen. “The Ninja and Their Secret Fighting Art.” 1981: 18-21</ref> |

|||

Ninjutsu was developed as a collection of fundamental survivalist techniques in the warring state of [[feudal Japan]]. The ninja used their art to ensure their survival in a time of violent political turmoil. Ninjutsu included methods of gathering information, and techniques of non-detection, avoidance, and misdirection. Ninjutsu can also involve training in [[free running]], [[disguise]], [[escapology|escape]], [[wikt:hiding|concealment]], [[archery]], and [[medicine]].<ref>Hatsumi, Masaaki. “Ninjutsu: History and Tradition.” June 1981</ref> |

|||

Skills relating to espionage and assassination were highly useful to warring factions in feudal Japan. These persons were literally called {{nihongo|"non-humans"|非人|hinin}}.<ref name="Draeger-Bujutsu">{{cite book| last = Draeger| first = Donn F.| authorlink = Donn F. Draeger| title = Classical Bujutsu: The Martial Arts and Ways of Japani| publisher = Weatherhill| date = 1973, 2007| location = Boston, Massachusetts| pages = 84–85| isbn = 978-0-8348-0233-9}}</ref> At some point the skills of espionage became known collectively as ninjutsu, and the people who specialized in these tasks were called ''shinobi no mono''. |

|||

==The eighteen skills== |

==The eighteen skills== |

||

Revision as of 00:07, 11 August 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

| |

| Also known as | Ninjitsu, Ninpō, Shinobi-jutsu |

|---|---|

| Hardness | Non-competitive |

| Country of origin | |

| Creator | Ninja |

| Parenthood | Military Tactics |

Ninjutsu (忍術) sometimes used interchangeably with the modern term ninpō (忍法)[1] is the martial art, strategy, and tactics of unconventional warfare and guerrilla warfare as well as the art of espionage purportedly practiced by the shinobi (commonly known outside of Japan as ninja).[2] Ninjutsu was more an art of tricks, than a martial art.[3] Ninjutsu was a separate discipline in some traditional Japanese schools, which integrated study of more conventional martial arts along with shurikenjutsu, kenjutsu, sojutsu, bōjutsu, battlefield grappling kumi-uchi (an old form jujutsu) and others.[4]

While there are several styles of modern ninjutsu, the historical lineage of these styles is disputed. Some schools and masters claim to be the only legitimate heir of the art, but ninjutsu is not centralized like modernized martial arts such as judo or karate. Togakure-ryū claims to be the oldest recorded form of ninjutsu, and claims to have survived past the 1500s.[5]

History

Spying in Japan dates as far back as Prince Shōtoku (572–622), although the origins of the Ninja date much earlier.[6] According to Shōninki, the first open usage of ninjutsu during a military campaign was in the Gempei War, when Minamoto no Kuro Yoshitsune chose warriors to serve as shinobi during a battle; this manuscript goes on to say that, during the Kenmu era, Kusonoki Masashige used ninjutsu frequently. According to footnotes in this manuscript, the Gempei war lasted from 1180 to 1185, and the Kenmu Restoration occurred between 1333 and 1336.[7] Ninjutsu was developed by groups of people mainly from the Iga Province and Kōka, Shiga of Japan.[citation needed] Throughout history the shinobi have been seen as assassins, scouts and spies who were hired mostly by territorial lords known as the Daimyo. They conducted operations that the samurai were forbidden to partake in.[8] They are mainly noted for their use of stealth and deception. Throughout history many different schools (ryū) have taught their unique versions of ninjutsu. An example of these is the Togakure-ryū. This ryū was developed after a defeated samurai warrior called Daisuke Togakure escaped to the region of Iga. Later he came in contact with the warrior-monk Kain Doshi who taught him a new way of viewing life and the means of survival (ninjutsu).[9]

Ninjutsu was developed as a collection of fundamental survivalist techniques in the warring state of feudal Japan. The ninja used their art to ensure their survival in a time of violent political turmoil. Ninjutsu included methods of gathering information, and techniques of non-detection, avoidance, and misdirection. Ninjutsu can also involve training in free running, disguise, escape, concealment, archery, and medicine.[10]

Skills relating to espionage and assassination were highly useful to warring factions in feudal Japan. These persons were literally called "non-humans" (非人, hinin).[11] At some point the skills of espionage became known collectively as ninjutsu, and the people who specialized in these tasks were called shinobi no mono.

The eighteen skills

According to Bujinkan members, Ninja Jūhakkei ("the eighteen disciplines") were first stated in the scrolls of Togakure-ryū.[citation needed] They became definitive for all ninjutsu schools.[citation needed]

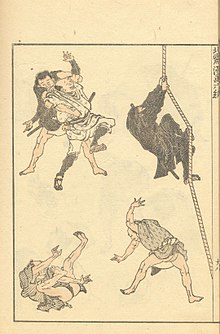

Ninja jūhakkei was often studied along with Bugei Jūhappan (the "eighteen samurai fighting art skills"). Though some are used in the same way by both samurai and ninja, other techniques were used differently by the two groups (ninja martial arts was adaptation to surprise attacks at night, in the back or ambush and at espionage to stun the enemy for escape in case of detection). Ninja fought in the lack of space (thicket bush in the forest, narrow corridors and low rooms locks).[12]

The 18 disciplines are:[13]

- Seishinteki kyōyō – spiritual refinement

- Taijutsu – unarmed combat

- Kenjutsu – sword techniques

- Bōjutsu – stick and staff techniques

- Sōjutsu – spear techniques

- Naginatajutsu – naginata techniques

- Kusarigamajutsu – kusarigama techniques

- Shurikenjutsu – throwing weapons techniques

- Kayakujutsu – pyrotechnics

- Hensōjutsu – disguise and impersonation

- Shinobi-iri – stealth and entering methods

- Bajutsu – horsemanship

- Sui-ren – water training

- Bōryaku – tactics

- Chōhō – espionage

- Intonjutsu – escaping and concealment

- Tenmon – meteorology

- Chi-mon – geography

The name of the discipline of taijutsu (体術), literally means "body skill" or "body art". Historically, the word taijutsu is often (in Japan) used interchangeably with jujutsu (as well as many other terms) to refer to a range of grappling skills. The term is also used in the martial art of aikido to distinguish the unarmed fighting techniques from other (e.g., stick fighting) techniques. In ninjutsu, especially since the emergence of the ninja movie genre in the '80s, it is also used to avoid the undesired bravado of explicitly referring to ninja combat techniques.

Weapons and equipment

The following tools may not be exclusive to the ninja, but they are commonly associated with the practice of ninjutsu.

Composite and articulated weapons

- Kusarigama - kama linked to a weight, either by a long rope or chain

- Kyoketsu shoge - hooked rope-dart, featuring a metal ring on the opposite end

- Bō - long wooden staff designed for power strikes

- Kusari-fundo, also known as manriki or manriki-gusari - a chain and weight weapon.

Fistload weapons

- Kakute - rings resembling modern wedding bands with concealed, often poison-tipped spines, typically worn by kunoichi and enabling ninja to quietly strangle enemies with the pointed ends against the neck or throat

- Shobo - a jabbing or piercing weapon, similar in shape to kubotan and yawara, but often featuring a center grip ring

- Shuriken - various small hand held weapons including "throwing stars" that could be used to stab, slash or they could be thrown

- Tekko - an earlier version of brass knuckles

- Tessen - a folding fan with an iron frame. it could be used to club, or cut and slash the enemy

- Jutte - A weapon similar to the Sai

Modified tool weapons

- Kunai - multi-purpose tool

- Shikoro - used as a tool for opening doors and stabbing or slashing

Projectile weapons

- Fukiya - Japanese blowgun, typically firing poison darts

- Makibishi/tetsubishi - the Japanese type of caltrop

- Shuriken - various small hand held weapons including throwing stars and throwing darts that could be used to stab, slash or they could be thrown

- Yumi and Ya - traditional Japanese bow and arrow

- Bo-hiya (Japanese fire arrow) - fire arrow

- Tekagi-shuko and Neko-te - hand "claw" weapons

- Chackrams - disk like projectiles like boomerangs

Staffs and polearms

- Hanbo, bō, jō, and tambo - various sized staff weapons

- Yari - traditional Japanese spear that's similar to the naginata

- Nagamaki - pole arm with roughly equal length blade and handle

- Naginata - traditional Japanese pole-arm used by women and samurai (example: women might protect their home with a naginata)

Swords

- Katana - a long curved and single-edged sword, more commonly used by samurai (or ninja disguised as samurai)

- Wakizashi - short sword that can be hidden on the ninja's body, also a backup weapon

- Ninjato - an edged weapon used by ninja as swords. Ninjato can be stolen katana from samurai or forged by ninja themselves with varying lengths

- Tantō - dagger

- Kaiken (dagger)- Similar to the tantō

- Bokken - traditional wooden sword use in Japanese martial arts typically modeled off of katanas

- Shinai - bamboo sword used in kendo

Stealth tools

- Kaginawa or grappling hook - climbing and Hojojutsu composite tool that also functioned as a makeshift gaff hook weapon

- Shinobi shōzoku - the reputed ninja clothing.

- Ono (weapon) - Japanese axe and hatchet

See also

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2012) |

- ^ T.A. Green, J.R. Svinth. Martial arts of the world: An Encyclopedia of History and innovation. East Asia. Japan:Ninpo

- ^ Hayes, Stephen. The Ninja and Their Secret Fighting Art. ISBN 0-8048-1656-5, Tuttle Publishing, 1990

- ^ BBC News, Japan. By Mariko Oi. Japan's ninjas heading for extinction. Five nearly-true ninja myths

- ^ Gorbylev, Alexey (2010), Ninja:martial art. What is Ninjutsu?, Jauza, ISBN 978-5-457-06007-4

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - ^ Togakure-ryū

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie. "History of the Ninja", About.com, accessed June 2, 2011.

- ^ Masazumi, Natori, translated by Editions Albin Michel and Jon E. Graham. "Shoninki: the Secret Teachings of the Ninja; the 17th-Century Manual on the Art of Concealment", English Translation Copyright 2010 by Inner Trditions International.

- ^ Shinobi-Do Ninjutsu

- ^ Hayes, Stephen. “The Ninja and Their Secret Fighting Art.” 1981: 18-21

- ^ Hatsumi, Masaaki. “Ninjutsu: History and Tradition.” June 1981

- ^ Draeger, Donn F. (1973, 2007). Classical Bujutsu: The Martial Arts and Ways of Japani. Boston, Massachusetts: Weatherhill. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-8348-0233-9.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Горбылев 2001, p. 33-37

- ^ Books.google.com

Further reading

- Hatsumi, Masaaki. Essence of Ninjutsu, 1988. ISBN 0-8092-4724-0

- Callos, Tom. "Notable American Martial Artists", Black Belt Magazine, May 2007, pp. 72–73.

- Hatsumi, Masaaki. Ninjutsu: History and Tradition, 1981. ISBN 0-86568-027-2

- Hatsumi, Masaaki. Ninpo: Wisdom for Life, 1998. ISBN 1-58776-206-4, ISBN 0-9727738-0-0

- Hayes, Stephen K. The Ninja and their Secret Fighting Art, 1990. ISBN 0-8048-1656-5

- Dillon, Thomas. Wingspan: Culture-Society-People in Japan, Where Have All the Ninja Gone?, September 2007, No.459.

- Hiroshi, Kuroi. Historical group image editorial staff compilation, 2007. ISBN 978-4-05-604814-8

- Toshitora, Yamashiro. Secret Guide to Making Ninja Weapons, Butokukai Press, 1986. ISBN 978-99942-913-1-1

- DiMarzio, Daniel. A Story of Life, Fate, and Finding the Lost Art of Koka Ninjutsu in Japan, 2008. ISBN 978-1-4357-1208-9

- Bertrand, John. "Techniques that made ninjas feared in 15th-century Japan still set the standard for covert ops", Military History 23(1), March 2006, pp. 12–19. Retrieved on July 11, 2008 from Academic Search Premier database.

- Hayes, Stephen K. and Masaaki Hatsumi. Secrets from the Ninja Grandmaster (Rev. Ed.), 2003. Boulder, Colorado; Paladin Press.

- Zoughari, Kacem. The Ninja: Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan, Tuttle Publishing, 2010. ISBN 0-8048-3927-1

- T.A. Green, J.R. Svinth. Martial arts of the world: An Encyclopedia of History and innovation. East Asia. Japan:Ninpo

- Gorbylev, Alexey (2010), Ninja:martial art, Jauza, ISBN 978-5-457-06007-4

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - Горбылев, Алексей (2001), Когти Невидимок. Оружие и снаряжение ниндзя, Харвест, ISBN 985-13-0621-5

External links

- Ninjutsu techniques Ninjutsu kata and techniques in the AKBAN wiki

- Ninjutsu History History of Ninjutsu and Its Evolution