Fan Noli: Difference between revisions

Mr Stephen (talk | contribs) clean up, straight quotes, ellipsis format, dashes in year ranges, ISBN format using AWB |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.2.7.1) |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{commons category|Fan Stilian Noli}} |

{{commons category|Fan Stilian Noli}} |

||

*{{cite web|last=Elsie|first=Robert|chapter=Classical Authors: Fan Noli|title=Albanian Literature in Translation|url=http://www.albanianliterature.net/authors_classical/noli.html}} |

*{{cite web|last=Elsie |first=Robert |chapter=Classical Authors: Fan Noli |title=Albanian Literature in Translation |url=http://www.albanianliterature.net/authors_classical/noli.html |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100201044157/http://www.albanianliterature.net:80/authors_classical/noli.html |archivedate=2010-02-01 |df= }} |

||

{{s-start}} |

{{s-start}} |

||

Revision as of 16:09, 29 December 2016

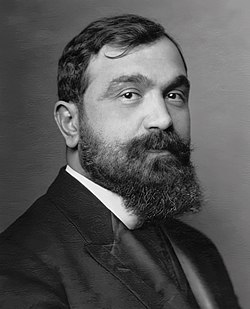

Fan Stilian Noli | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th Prime Minister of Albania | |

| In office June 16, 1924 – December 23, 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Iliaz Vrioni |

| Succeeded by | Iliaz Vrioni |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 6, 1882 Ibriktepe, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | March 13, 1965 (aged 83) Fort Lauderdale, Florida |

| Political party | Independent (Albanian nationalist) |

| Alma mater | Harvard,[1] Boston University |

| Occupation | Writer, Bishop, Translator, Composer, Politician |

| Profession | Priest and Politician |

Theofan Stilian Noli, better known as Fan Noli (January 6, 1882 – March 13, 1965) was an Albanian writer, scholar, diplomat, politician, historian, orator, and founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church, who served as prime minister and regent of Albania in 1924 during the June Revolution.

Fan Noli is venerated in Albania as a champion of literature, history, theology, diplomacy, journalism, music, and national unity. He played an important role in the consolidation of Albanian as the national language of Albania with numerous translations of world literature masterpieces.[2] His contributions to English language literature are also manifold: as a scholar and author of a series of publications on Skanderbeg, Shakespeare, Beethoven, religious texts and translations.[2] He produced a translation of the New Testament in English, The New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ from the approved Greek text of the Church of Constantinople and the Church of Greeze, published in 1961.

He earned degrees at Harvard [1] (1912), the New England Conservatory of Music (1938), and finally his Ph.D. from Boston University (1945).[3] He was ordained a priest in 1908, establishing thereby the Albanian Church and elevating the Albanian language to ecclesiastic use. He briefly resided in Albania after the 1912 declaration of independence. After World War I, Noli led the diplomatic efforts for the reunification of Albania and received the support of US President Woodrow Wilson. Later he pursued a diplomatic-political career in Albania, successfully leading the Albanian bid for membership in the League of Nations.

A respected figure who remained critical of corruption and injustice in the Albanian government, Fan Noli was asked to lead the 1924 June Revolution. He then served as prime minister until his revolutionary government was overthrown by Ahmet Zogu. He was exiled to Italy and permanently settled in the United States in the 1930s, acquiring US citizenship and agreeing to end his political involvement. He spent the rest of his life as an academician, religious leader and writer.

Background

Fan Noli was born in 1882 in the Albanian community of Ibrik Tepe, Eastern Thrace (then part of the Ottoman Empire) as Theofanes Stylianos Mavromatis.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11] He was an Albanian[12][13] of the Eastern Orthodox faith. As a young man, Noli wandered throughout the Mediterranean Basin, living in Athens, Greece, Alexandria, Egypt and Odessa, Russia, and supported himself as an actor and translator. As well as his native Albanian, he spoke many languages such as Greek, English, French, Turkish, and Arabic.[14] The Greek diplomat and author Alexis Kyrou claims that Noli "had not yet discovered his "Albanian" patriotism when he was still a teacher in the Greek schools of Alexandria and had the name Theophanis Mavromatis".[15] Through his contacts with the Albanian expatriate movement, he became an ardent supporter of his country's nationalist movement and moved to the United States in 1906. He first worked in Buffalo, New York, in a lumber mill and then moved to Boston, Massachusetts and worked as an operator on a machine which stamped labels on cans.[14]

Hudson Incident

In Boston, some Albanian Christians were part of the Greek Orthodox Church, which was vehemently opposed to the Albanian nationalist cause. When a Greek Orthodox priest refused to perform the burial rites for Kristaq Dishnica, a member of the Albanian community from Hudson, Massachusetts, because of his nationalist activities, Noli and a group of Albanian nationalists in New England created the independent Albanian Orthodox Church. Noli, the new church's first clergyman, was ordained as a priest in 1908 by a Russian Orthodox bishop in the United States under questionable circumstances.[14] In 1923, Noli was consecrated as a bishop for the Church of Albania.

Political activities

In 1908, Noli began studying at Harvard, completing his degree in 1912. He returned to Europe to promote Albanian independence, setting foot in Albania for the first time in 1913. He returned to the United States during World War I, serving as head of the Vatra organization, which effectively made him leader of the Albanian diaspora. His diplomatic efforts in the United States and Geneva won the support of President Woodrow Wilson for an independent Albania and, in 1920, earned the new nation membership in the fledgling League of Nations. Though Albania had already declared its independence in 1912, membership in the League of Nations provided the country with the international recognition it had failed to obtain until then.

In 1921, Noli entered the Albanian parliament as a representative of the liberal pro-British "People's Party" (Albanian: Partia e Popullit), the chief liberal movement in the country. The other parties were the conservative pro-Italian "Progressive Party" (Albanian: Partia Përparimtare) founded by Mehdi Frashëri and led by Ahmet Zogu, and "Popular Party" (Albanian: Partia Popullore) of Xhafer Ypi. The conservatives of Zogu would dominate the political scene.[16][17]

Noli served briefly as foreign minister in the government of Xhafer Ypi. This was a period of intense turmoil in the country between the liberals and the conservatives. After a botched assassination attempt against Zogu, the conservatives revenged themselves by assassinating another popular liberal politician, Avni Rustemi. Noli's speech at Rustemi's funeral was so powerful that liberal supporters rose up against Zogu and forced him to flee to Yugoslavia (March 1924). Zogu was succeeded briefly by his father-in-law, Shefqet Vërlaci, and by the liberal politician Iliaz Vrioni; Noli was named prime minister and regent on July 17, 1924.

Noli was consecrated in 1923 as the senior Orthodox bishop of the newly proclaimed Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania out of the Congress of Berat.

Downfall and exile

Despite his efforts to reform the country, Noli's "Twenty Point Program" was unpopular, and his government was overthrown by groups loyal to Zogu on Christmas Eve of that year. Two weeks later, Zogu returned to Albania, and Noli fled to Italy under sentence of death.

Conscious of his fragile position, Zogu took drastic measures to consolidate his reassert in power. By the end of winter, two of the main leaders of the opposition, Bajram Curri and Luigj Gurakuqi, were assassinated, while others were imprisoned. Noli founded the "National Revolutionary Committee" (Albanian: Komiteti Nacional Revolucionar) also known as KONARE in Vienna. The committee published the periodical called "National Freedom" (Albanian: Liria Kombëtare). Some of the early Albanian communists as Halim Xhelo or Riza Cerova would start their publishing activities here. The committee aimed in overthrowing Zogu and his cast and restoring democracy. Despite the efforts, the committee's access and influence in Albania would be limited. With the intervention of Kosta Boshnjaku, an old communist and KONARE member, the organization would receive unconditioned monetary support from the Comintern. Also Noli and Boshnjaku would make possible for exile members of the Committee for the National Defence of Kosovo (outlawed by Zogu) to get the same financial support.[18]

In 1928, KONARE changed its name to "Committee of National Liberation" (Albanian: Komiteti i Çlirimit Kombëtar). Meanwhile, in Albania, after three years of republican regime, the "National Council" declared Albania a Constitutional Monarchy, and Ahmet Zogu became king.[19] Noli moved back to the United States in 1932 and formed a republican opposition to Zogu, who had since proclaimed himself "King Zog I". Over the next years, he continued his education, studying and later teaching Byzantine music, and continued developing and promoting the autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church he had helped to found. While in exile, he briefly allied with King Zog, who fled Albania before the invading Italians in 1939, but was unable to set a firm anti-Axis, anti-Communist front.

After the war, Noli established some ties with the communist government of Enver Hoxha, which seized power in 1944. He unsuccessfully urged the U.S. government to recognize the regime, but Hoxha's increasing persecution of all religions prevented Noli's church from maintaining ties with the Orthodox hierarchy in Albania. Despite the Hoxha regime's anticlerical bent, Noli's ardent Albanian nationalism brought the bishop to the attention of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI's Boston office kept the bishop under investigation for more than a decade with no final outcome to the probe.

In 1945, Fan S. Noli received a doctor's degree in history from Boston University, writing a dissertation on Skanderbeg. In the meantime, he also conducted research at Boston University Music Department, publishing a biography on Ludwig van Beethoven. He also composed a one-movement symphony called Scanderbeg in 1947. Toward the end of his life, Noli retired to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where he died in 1965. The branch of the Albanian Orthodox Church that he had governed eventually became the Albanian Archdiocese of the Orthodox Church in America.

Writing in his diary two days after Noli's death, Albanian leader Enver Hoxha gave his analysis of Noli's work:[20]

As we are informed, Fan S. Noli died from an operation done last week in which, because of his age, he did not survive. A cerebral hemorrhage caused a quick death. Noli was one of the prominent political and literary figures of the beginning of this century. The balance sheet of his life was positive ... Fan Noli today enjoys a great popularity in our country, deserved as a literary translator and music critic. He was a prominent promoter of the Albanian language. His original works and translations, especially of Shakespeare, of Omar Khayyám and Blasco Ibáñez, are immortal. But especially his anti-Zogist, anti-feudal elegies and poems are beautiful jewels that have inspired and will inspire our youth, especially in creativity. He was also respected as a realistic politician, as a revolutionary democrat in ideology and politics. The Party has assessed the figure of Noli. As is deserved, we have had a patriotic duty to point out the really great merits of his in literature, the history of the arts, and his merits and weaknesses in politics. I think we will do our best in bringing his body to Albania, as this distinguished son of the people, the revolutionary patriot, deserves to bask in his homeland, which he loved and fought for his entire life.

— Enver Hoxha

Fan S. Noli is depicted on the obverse of the Albanian 100 lekë banknote issued in 1996 though the banknote itself has ceased being legal tender since December 31, 2008.[21]

Poems

The following poems were written by Fan Noli:

- Hymni i Flamurit

- Thomsoni dhe Kuçedra

- Jepni për Nënën

- Moisiu në mal

- Marshi i Krishtit

- Krishti me kamçikun

- Shën Pjetrin në Mangall

- Marshi i Barabbajt

- Marshi i Kryqësmit

- Kirenari

- Kryqësmi

- Kënga e Salep-Sulltanit

- Syrgjyn-vdekur

- Shpell' e Dragobisë

- Rent, or Marathonomak!

- Anës lumejve

- Plak, topall dhe ashik

- Sofokliu

- Tallja përpara Kryqit

- Sulltani dhe kabineti

- Saga e Sermajesë

- Lidhje e paçkëputur

- Çepelitja

- Vdekja e Sulltanit

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b Thernstrom 1980, p. 26.

- ^ a b Spahiu & Mjeku 2009.

- ^ p. 175. William Paul. 2003. English Language Bible Translators. Jefferson, NC & London: McFarland and Co.

- ^ Curtis 1994, p. 465: "Born Theophanus Stylianos Mavromatis in Imbrik-Tepe, a predominantly Albanian settlement in Thrace, then part of the Ottoman Empire, Fan Stylian Noli was educated in the Greek Gymnasium of Edirne (Adrianople)."

- ^ Stavrou 1996, p. 40: "Fan Noli was born Theofanis Stylianou Mavromates in the village of Ibrik-Tepe of Adrianoupolis (today in Turkish Thrace) in 1882."

- ^ The Central European Observer 1943, p. 63: "But Theophanus Mavromatis, which was Fan Noli's original name, came in 1900, after assisting in an ironmonger's shop, to Adrianople, where the good teachers gave him an education."

- ^ Baerlein 1968, p. 76: "... year 1900 his name was Theophanus Mavromatis, which is Greek."

- ^ Free Europe 1941, p. 278: "The one personage as to whom Mr. Robinson seems to be misinformed is Bishop Fan Noli, who has for many years lived in the United States and whom Mr. Robinson probably did not meet ... He says that this former Premier was born in the south of the country, was educated at Harvard and was consecrated a Bishop in Greece. The facts are that he was born near Adrianople and that his original name was Theophanos Mavromatis, which does not necessarily imply that he was Greek."

- ^ Irénikon 1963, p. 266: "Il était connu alors sous le nom de Théophanis Mavromatis."

- ^ Ekdotiki 2000, p. 538: "158 Stylianou Theophanes Noli or Mavrommatis."

- ^ Giakoumēs, Vlassas & Hardy 1996, p. 184 "His full name was Theophanis Stylianos Mavrommatis, and he was born in Adrianople and studied in Athens and the USA. ... "

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=1TPUAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA34&dq=theofan+noli+albanian&hl=en&sa=X&ei=p0JOU7jGEMndtAbxhIHQCQ&redir_esc=y "one of the mos colorfull Albanian politicians"

- ^ Constance J. Tarasar (1975), Orthodox America, 1794–1976: Development of the Orthodox Church in America, Syosset, N.Y: Orthodox Church in America, Department of History and Archives, p. 311, OCLC 2930511,

It was from his family that Fan Noli received a sense of identity as an Albanian

- ^ a b c Austin 2012, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Kyrou (or Kyros) Ad. Alexis, Our Balcanian neighbors", 1962, p. 28 : "... όταν υπηρέτει ακόμη ως δημοδιδάσκαλος εις τα Ελληνικά σχολεία της Αιγύπτου και δεν είχεν, εισέτι, ανακαλύψει τον "Αλβανικόν" του πατριωτισμόν, ωνομάζετο Θεοφάνης Μαυρομάτης ...".

- ^ Brisku 2013, p. 75: "Two political groupings: the proBritish People's Party, headed by the colourful leader, Fan Noli, and the pro—Italian Progressive Party, led by Mehdi Frashéri, came to dominate the political scene."

- ^ Bogdani & Loughlin 2009, p. 122: "The first Albanian political parties, in the western meaning of the word, appeared in the early 1920s, the most prominent being: the Progressive Party led by Ahmet Zogu, the People's Party led by Fan Noli, and the Popular Party led by Xhafer Ypi."

- ^ Vllamasi & Verli 2000, "Një pjesë me rëndësi e emigrantëve, me inisiativën dhe ndërmjetësinë e Koço Boshnjakut, u muarrën vesh me "Cominternin", si grup, me emër "KONARE" (Komiteti Revolucionar Kombëtar), për t'u ndihmuar pa kusht gjatë aktivitetit të tyre nacional, ashtu siç janë ndihmuar edhe kombet e tjerë të vegjël, që ndodheshin nën zgjedhë të imperialistëve, për liri e për pavarësi. Përveç kësaj pjese, edhe emigrantët kosovarë irredentistë, të grupuar e të organizuar nën emrin "Komiteti i Kosovës", si grup, u ndihmuan edhe ata nga "Cominterni"."

- ^ Ersoy, Górny & Kechriotis 2010, p. 155.

- ^ Hoxha, Enver (1989). "Ditar: 1965". Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House. pp. 172–174.

- ^ Bank of Albania (2004–2012). "Banknotes Withdrawn from Circulation". Bank of Albania.

Sources

- Athene (1944). Athene. Chicago, IL: Athene Enterprises, Incorporated.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Austin, Robert Clegg (2012). Founding a Balkan State: Albania's Experiment With Democracy, 1920–1925. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-4435-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Baerlein, Henry (1968). Southern Albania: Under the Acroceraunian Mountains. Chicago: Argonaut.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bogdani, Mirela; Loughlin, John (2009) [2007]. Albania and the European Union: The Tumultuous Journey Towards Integration and Accession. Library of European Studies. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-308-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Binder, David (2004). "Vlachs: A Peaceful Balkan People" (PDF). Mediterranean Quarterly. 15 (4). Duke University Press: 115–124. doi:10.1215/10474552-15-4-115.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brisku, Adrian (2013). Bittersweet Europe: Albanian and Georgian Discourses on Europe, 1878–2008. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-985-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curtis, Ference Gregory (1994). Chronology of 20th-century Eastern European History. Detroit, MI: Gale Research, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8103-8879-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ekdotiki, Athenon (2000). The Splendour of Orthodoxy: 2000 years history, monuments, art. Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe. Vol. 3. Budapest and New York: Ekdotiki Athenon. ISBN 978-960-213-398-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ersoy, Ahmet; Górny, Maciej; Kechriotis, Vangelis (2010). Modernism: Representations of National Culture. Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe. Vol. 3. Budapest and New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-7326-64-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Free Europe (1941). Free Europe: Fortnightly Review of International Affairs (Volumes 4–5). London: Free Europe.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Giakoumēs, Geōrgios K.; Vlassas, Grēgorēs; Hardy, David A. (1996). Monuments of Orthodoxy in Albania. Doukas School. ISBN 978-960-7203-09-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Irénikon (1963). Irénikon (Volume 36) (in French). Amay, Belgium: Monastère Bénédictin.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Naval Society (1928). The Naval Review (Volume 16). London: Naval Society.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spahiu, Avni; Mjeku, Getoar (2009). Fan Noli's American Years: Notes on a Great Albanian American. Houston, TX: Jalifat Group. ISBN 978-0-9767140-2-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stavrou, Nikolaos A. (1996). "Albanian Communism and the 'Red Bishop'". Mediterranean Quarterly. 7 (2): 32–59.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - The Central European Observer (1943). The Central European Observer (Volume 20). Prague: "Orbis" Publishing Company.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thernstrom, Stephan (1980). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-37512-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vllamasi, Sejfi; Verli, Marenglen (2000). Ballafaqime Politike në Shqipëri (1897–1942): Kujtime dhe Vlerësime Historike. Tirana: Shtëpia Botuese "Neraida". ISBN 99927-713-1-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania and King Zog: Independence, Republic and Monarchy 1908–1939. London: Center for Albanian Studies. ISBN 978-1-84511-013-0.

External links

- Elsie, Robert. "Albanian Literature in Translation". Archived from the original on 2010-02-01.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- 1882 births

- 1965 deaths

- 20th-century Albanian clergy

- 20th-century Eastern Orthodox bishops

- Albanian religious leaders

- Eastern Orthodox Christians from Albania

- Primates of the Albanian Orthodox Church

- Prime Ministers of Albania

- Albanian revolutionaries

- 20th-century Albanian writers

- Albanian translators

- Translators to Albanian

- English–Albanian translators

- Albanian historians

- Harvard University alumni

- Albanian expatriates in Ukraine

- Albanian expatriates in the United States

- Albanian emigrants to the United States

- People from Edirne Province

- Albanian diplomats

- 20th-century translators

- 20th-century Albanian politicians

- Translators of the Bible into English

- Translators of the Bible into English who were not native speakers

- Albanian expatriates in Egypt

- 20th-century historians

- 19th-century Albanian writers

- 19th-century Albanian poets

- 20th-century Albanian poets

- Albanian expatriates in Austria

- Albanian communists

- Albanian male writers

- Albanian male poets

- 19th-century male writers