Assyrian homeland: Difference between revisions

Tag: references removed |

|||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

=== |

===Old Assyrian Empire=== |

||

{{Main |

{{Main|Old Assyrian Empire}} |

||

{{further|List of Assyrian kings}} |

|||

[[File:Neo-Assyrian_Empire.jpg|thumb|right|The Neo-Assyrian empire at its greatest extent, 671 B.C.]] |

|||

[[File:Transport of cedar Dur Sharrukin.jpg|thumb|Relief from Assyrian capital of [[Dur Sharrukin]], showing transport of Lebanese cedar (8th century BC)]] |

|||

The cities of [[Assur|Aššur]] and [[Nineveh]] (modern day, [[Mosul]]), together with a number of other Assyrian cities, seem to have been established by 2600 BC. However it is likely that they were initially Sumerian-dominated administrative centres. In the late 26th century BC, [[Eannatum]] of [[Lagash]], then the dominant [[Sumer]]ian ruler in Mesopotamia, mentions "smiting [[Subartu]]" (Subartu being the Sumerian name for Assyria). Similarly, in ''c.'' the early 25th century BC, [[Lugal-Anne-Mundu]] the king of the Sumerian state of [[Adab (city)|Adab]] lists Subartu as paying tribute to him.<ref>Bertman, Stephen (2003). ''Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia''. Oxford University Press. p. 94. {{ISBN|978-019-518364-1}}. Retrieved 16 May 2015.</ref> [[Assyria]] reached its greatest extent during the period of the [[Neo-Assyrian empire]], coming to dominate the Ancient Near East, East Mediterranean, Asia Minor, Caucasus, and parts of the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa, eclipsing and conquering rivals such as Babylonia, Elam, Persia, Urartu, Lydia, the Medes, Phrygians, Cimmerians, Israel, Judah, Phoenicia, Chaldea, Canaan, the Kushite Empire, the Arabs, and Egypt.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livius.org/li-ln/limmu/limmu_1c.html|title=Assyrian Eponym List|publisher=|accessdate=23 November 2014}}</ref><ref>Tadmor, H. (1994). ''The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, King of Assyria'', p.29</ref> |

|||

{{Infobox Former Country |

|||

Assyrians are eastern [[Aramaic]]-speaking, descending from pre-[[Islamic]] inhabitants of [[Upper Mesopotamia]]. The [[Old Aramaic language]] was adopted by the population of the [[Neo-Assyrian Empire]] from around the 8th century BC, and these eastern dialects remained in wide use throughout Upper Mesopotamia during the [[Persian Empire|Persian]] and [[Byzantine Empire|Roman]] periods, and survived through to the present day. The [[Syriac language]] evolved in [[Achaemenid Assyria]] during the 5th century BC.<ref name="Brinkman">{{cite book|title = The Oxford companion to the Bible|chapter = Assyria|author = J. A. Brinkman|editor = Bruce Manning Metzger, Michael David Coogan|publisher = Oxford University Press|year = 2001|page = 63}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">Biblical Archaeology Review May/June 2001: Where Was Abraham's Ur? by Allan R. Millard</ref> |

|||

|native_name = |

|||

|conventional_long_name = Old Assyrian Empire |

|||

|common_name = Assyria |

|||

|continent = Asia |

|||

|region = Near East |

|||

|era = Bronze Age |

|||

|government_type = Monarchy |

|||

|year_start = ''circa'' 2025 BC |

|||

|year_end = ''circa'' 1750 BC |

|||

|p1 = Early Assyrian kingdom |

|||

|flag_p1 = |

|||

|s1 = Kingdom of Mitanni |

|||

|flag_s1 = |

|||

|s2 = Middle Assyrian Empire |

|||

|flag_s2 = |

|||

|image_map = Samsi Addu.PNG |

|||

|image_map_caption = Map showing the approximate extent of the<br>Upper Mesopotamian Empire<br> at the death of Shamshi-Adad I ''c.'' 1721 BC. |

|||

|capital = [[Assur|Aššur]] |

|||

|common_languages = [[Akkadian language]] <br>[[Sumerian language|Sumerian]] |

|||

|religion = [[Ancient Mesopotamian religion]] |

|||

|leader1 = [[Erishum I]] (first) |

|||

|leader2 = [[Ashur-nadin-ahhe II]] (last) |

|||

|year_leader1 = ''circa'' 2025 BC |

|||

|year_leader2 = ''circa'' 1393 BC |

|||

|title_leader = [[List of Assyrian kings|King]] |

|||

|today = Iraq, Syria and Turkey |

|||

}} |

|||

During the Assyrian period [[Duhok]] was named Nohadra (and also ''Bit Nuhadra''' or ''Naarda''), where, during the [[Parthian Empire|Parthian]]-[[Sassanid]] rule in Assyria (c.160 BC to 250 AD) as [[Beth Nuhadra]], gained semi-independence as one of a patchwork of [[Neo-Assyrian]] kingdoms in Assyria, which also included [[Adiabene]], [[Osroene]], [[Assur]] and [[Beth Garmai]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Société des études arméniennes, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Association de la revue des études arméniennes|title=Revue des études arméniennes, Volume 21|pages=303, 309|url=https://books.google.com/books?ei=17P9Tea_AoiG-waSs6i3Aw&ct=result&id=D_JfAAAAMAAJ&dq=nohadra&q=nohadra}}</ref><ref>[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0064%3Aalphabetic+letter%3DN NAARDA], Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854)</ref> |

|||

The Old Assyrian Empire is one of four periods into which the history of Assyria is divided, the other three being: the [[Early Period (Assyria)|Early Assyrian Period]], the [[Middle Assyrian Empire|Middle Assyrian Period]] and the [[Neo-Assyrian Empire|New Assyrian Period]]. Assyria was a major [[Mesopotamian]] [[Afro-Asiatic language|Afro-Asiatic]]-speaking kingdom and empire of the [[ancient Near East]]. Centered on the [[Tigris-Euphrates River System]] in [[Upper Mesopotamia]], the [[Assyrian people]] came to rule powerful empires at several times. Making up a substantial part of the "[[Cradle of Civilization]]", which included [[Sumer]], the [[Akkadian Empire]], and [[Babylonia]], Assyria was at the height of technological, scientific and cultural achievements at its peak. |

|||

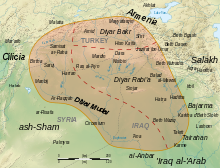

At its peak, the Assyrian empire ruled over what the [[ancient Mesopotamian religion]] referred to as the "[[Four Corners of the World]]": as far north as the [[Caucasus Mountains]] within the territory of present-day [[Armenia]] and the [[Republic of Azerbaijan]], as far east as the [[Zagros Mountains]] within the territory of present-day [[Islamic Republic of Iran]], as far south as the [[Arabian Desert]] of today's [[Kingdom of Saudi Arabia]], as far west as the island of [[Cyprus]] in the [[Mediterranean Sea]], and even further to the west in [[Egypt]] and eastern [[Libya]].<ref name="Albert Kirk Grayson 1972 108"/> |

|||

Assyria is named for its original capital, the ancient city of [[Aššur]], which dates to c. 2600 BC, originally one of a number of Akkadian city states in Mesopotamia. Assyria was also sometimes known as Subartu and Azuhinum prior to the rise of the city-state of Aššūr, after which it was Aššūrāyu, and after its fall. |

|||

[[Ushpia]] (2050–2030 BC) appears to have been the first fully urbanised independent king of Assyria, and is traditionally held to have dedicated temples to the god [[Ashur]] in the city of the same name.<ref>Poebel, Arno (1942). The Assyrian King List from Khorsabad, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 1/3, 253.</ref> He was followed by [[Sulili]], [[Kikkiya]] and [[Akiya]], of whom little is known aside from Kikkiya conducting various building works in Assur. |

|||

Assyria remained strong and secure; when Babylon was sacked and its Amorite rulers deposed by the [[Hittite Empire]], and subsequently fell to the [[Kassites]] in 1595 BC, both powers were unable to make any inroads into Assyria, and there seems to have been no trouble between the first Kassite ruler of Babylon, [[Agum II]], and [[Erishum III]] (1598–1586 BC) of Assyria, and a mutually beneficial treaty was signed between the two rulers. [[Shamshi-Adad II]] (1585–1580 BC), [[Ishme-Dagan II]] (1579–1562 BC) and [[Shamshi-Adad III]] (1562–1548 BC) seem also to have had peaceful tenures, although few records have thus far been discovered about their reigns. Similarly, [[Ashur-nirari I]] (1547–1522 BC) seems not to have been troubled by the newly founded [[Mitanni]] Empire in Asia Minor, the Hittite empire, or Babylon during his 25-year reign. He is known to have been an active king, improving the infrastructure, dedicating temples and conducting various building projects throughout the kingdom. |

|||

====Decline, 1450–1393 BC==== |

|||

[[File:Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia c. 1450 BC.png|thumb|250px|right|Overview map of the Ancient Near East in the 15th century BC (Middle Assyrian period), showing the core territory of Assyria with its two major cities [[Assur]] and [[Nineveh]] wedged between [[Babylonia]] downstream (to the south-east) and the states of [[Mitanni]] and [[Hittite Empire|Hatti]] upstream (to the north-west).]] |

|||

The emergence of the Mitanni Empire in the 16th century BC did eventually lead to a short period of sporadic [[Mitannian]]-[[Hurrian]] domination in the latter half of the 15th century. The Indo-European-speaking Mitannians are thought to have conquered and formed the ruling class over the indigenous Hurrians of eastern Anatolia. The Hurrians spoke a language isolate, i.e. neither Semitic nor Indo-European. |

|||

[[Ashur-nadin-ahhe I]] (1450–1431 BC) was courted by the Egyptians, who were rivals of Mitanni, and attempting to gain a foothold in the Near East. [[Amenhotep II]] sent the Assyrian king a tribute of gold to seal an alliance against the Hurri-Mitannian empire. It is likely that this alliance prompted [[Saushtatar]], the emperor of Mitanni, to invade Assyria, and sack the city of Ashur, after which Assyria became a sometime vassal state, with Ashur-nadin-ahhe I being deposed by Shaustatar and replaced by his own brother [[Enlil-nasir II]] (1430–1425 BC) in 1430 BC, who was then made to pay tribute to the Mitanni. [[Ashur-nirari II]] (1424–1418 BC) had an uneventful reign, and appears to have also paid tribute to the Mitanni Empire. |

|||

The Assyrian monarchy survived, and the Mitannian influence appears to have been short lived. |

|||

They appear not to have been always willing or indeed able to interfere in Assyrian internal and international affairs. |

|||

[[Ashur-bel-nisheshu]] (1417–1409 BC) seems to have been independent of Mitannian influence, as evidenced by his signing a mutually beneficial treaty with [[Karaindash]], the Kassite king of Babylonia in the late 15th century. He also undertook extensive rebuilding work in Ashur itself, and Assyria appears to have redeveloped its former highly sophisticated financial and economic systems during his reign. |

|||

[[Ashur-rim-nisheshu]] (1408–1401 BC) also undertook building work, strengthening the city walls of the capital. |

|||

[[Ashur-nadin-ahhe II]] (1400–1393 BC) also received a tribute of gold and diplomatic overtures from Egypt, probably in an attempt to gain Assyrian military support against Egypt's Mitannian and Hittite rivals in the region. However, the Assyrian king appears not to have been in a strong enough position to challenge Mitanni or the Hittites. |

|||

[[Eriba-Adad I]] (1392–1366 BC), a son of Ashur-bel-nisheshu, ascended the throne in 1392 BC and finally broke the ties to the Mitanni Empire, and instead began to exert Assyrian influence on the Mitanni. |

|||

===Early Christian period=== |

===Early Christian period=== |

||

Revision as of 01:36, 4 October 2018

The Assyrian homeland or Assyria refers to a geographic and cultural region situated in Northern Mesopotamia that has been traditionally inhabited by Assyrian people. The areas that form the Assyrian homeland are parts of present-day northern Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran and, more recently, northeastern Syria.[1][2] Moreover, the area that had the greatest concentration of Assyrians in the world until recently is located in the Assyrian Triangle, a region which comprises the Nineveh plains, southern Hakkari and the Barwari regions.[3] This is where some Assyrian groups seek to create an independent nation state.[4][1]

The Assyrian homeland roughly mirrors the boundaries of ancient Assyria proper, and the later Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid provinces of Assyria (Athura/Assuristan) that was extant between the 25th century BC and 7th century AD. The region was dissolved as a geo-political entity following the Arab Islamic conquest of Iraq in the late 7th century AD. Since the fall of the Iraqi Baath Party in 2003, and in the face of violence against the indigenous Assyrian Christian community, there has been a growing movement for Assyrian independence or autonomy.[5]

Assyrian-populated cities in Iraq include those in the Nineveh Governorate region in northern Iraq, such as, Alqosh, Tel Keppe, Batnaya, Bartella, Tesqopa, Karemlash, Bakhdida and, up until 2014, Mosul. There is an Assyrian minority in the Dohuk Governorate cities of Zakho and Duhok in Iraqi Kurdistan, which are also located within the Assyrian triangle.[6] In Turkey, the Tur Abdin region is the traditional cultural heartland for Assyrians and is the only remaining rural region in Turkey with a major Christian presence. However today, the majority of Assyrians in Turkey live in Istanbul. Northeastern Syria has in the latest century become a center for Assyrians, with much of the Assyrian population descending from refugees from Turkey that fled during the Assyrian Genocide and during later pogroms in Iraq. Major Assyrian population centras are Qamishli, al-Hasakah, Ras al-Ayn, Al-Malikiyah, Al-Qahtaniyah and the villages along the Khabur River in the Tell Tamer area.

The Assyrians, an indigenous pre-Arab, pre-Kurdish and pre-Turkic people of upper Mesopotamia, are predominantly Christian, adherents of the Church of the East, an East Syrian rite sect as well as; the Chaldean Catholic Church and Ancient Church of the East, or the Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Catholic Church, Assyrian Pentecostal Church and Assyrian Evangelical Church. They speak Neo-Aramaic languages, most common being; Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic and Turoyo.[7]

History

Old Assyrian Empire

Old Assyrian Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| circa 2025 BC–circa 1750 BC | |||||||||||

Map showing the approximate extent of the Upper Mesopotamian Empire at the death of Shamshi-Adad I c. 1721 BC. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Aššur | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian language Sumerian | ||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• circa 2025 BC | Erishum I (first) | ||||||||||

• circa 1393 BC | Ashur-nadin-ahhe II (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||||

• Established | circa 2025 BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | circa 1750 BC | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq, Syria and Turkey | ||||||||||

The Old Assyrian Empire is one of four periods into which the history of Assyria is divided, the other three being: the Early Assyrian Period, the Middle Assyrian Period and the New Assyrian Period. Assyria was a major Mesopotamian Afro-Asiatic-speaking kingdom and empire of the ancient Near East. Centered on the Tigris-Euphrates River System in Upper Mesopotamia, the Assyrian people came to rule powerful empires at several times. Making up a substantial part of the "Cradle of Civilization", which included Sumer, the Akkadian Empire, and Babylonia, Assyria was at the height of technological, scientific and cultural achievements at its peak.

At its peak, the Assyrian empire ruled over what the ancient Mesopotamian religion referred to as the "Four Corners of the World": as far north as the Caucasus Mountains within the territory of present-day Armenia and the Republic of Azerbaijan, as far east as the Zagros Mountains within the territory of present-day Islamic Republic of Iran, as far south as the Arabian Desert of today's Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, as far west as the island of Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea, and even further to the west in Egypt and eastern Libya.[8]

Assyria is named for its original capital, the ancient city of Aššur, which dates to c. 2600 BC, originally one of a number of Akkadian city states in Mesopotamia. Assyria was also sometimes known as Subartu and Azuhinum prior to the rise of the city-state of Aššūr, after which it was Aššūrāyu, and after its fall.

Ushpia (2050–2030 BC) appears to have been the first fully urbanised independent king of Assyria, and is traditionally held to have dedicated temples to the god Ashur in the city of the same name.[9] He was followed by Sulili, Kikkiya and Akiya, of whom little is known aside from Kikkiya conducting various building works in Assur.

Assyria remained strong and secure; when Babylon was sacked and its Amorite rulers deposed by the Hittite Empire, and subsequently fell to the Kassites in 1595 BC, both powers were unable to make any inroads into Assyria, and there seems to have been no trouble between the first Kassite ruler of Babylon, Agum II, and Erishum III (1598–1586 BC) of Assyria, and a mutually beneficial treaty was signed between the two rulers. Shamshi-Adad II (1585–1580 BC), Ishme-Dagan II (1579–1562 BC) and Shamshi-Adad III (1562–1548 BC) seem also to have had peaceful tenures, although few records have thus far been discovered about their reigns. Similarly, Ashur-nirari I (1547–1522 BC) seems not to have been troubled by the newly founded Mitanni Empire in Asia Minor, the Hittite empire, or Babylon during his 25-year reign. He is known to have been an active king, improving the infrastructure, dedicating temples and conducting various building projects throughout the kingdom.

Decline, 1450–1393 BC

The emergence of the Mitanni Empire in the 16th century BC did eventually lead to a short period of sporadic Mitannian-Hurrian domination in the latter half of the 15th century. The Indo-European-speaking Mitannians are thought to have conquered and formed the ruling class over the indigenous Hurrians of eastern Anatolia. The Hurrians spoke a language isolate, i.e. neither Semitic nor Indo-European. Ashur-nadin-ahhe I (1450–1431 BC) was courted by the Egyptians, who were rivals of Mitanni, and attempting to gain a foothold in the Near East. Amenhotep II sent the Assyrian king a tribute of gold to seal an alliance against the Hurri-Mitannian empire. It is likely that this alliance prompted Saushtatar, the emperor of Mitanni, to invade Assyria, and sack the city of Ashur, after which Assyria became a sometime vassal state, with Ashur-nadin-ahhe I being deposed by Shaustatar and replaced by his own brother Enlil-nasir II (1430–1425 BC) in 1430 BC, who was then made to pay tribute to the Mitanni. Ashur-nirari II (1424–1418 BC) had an uneventful reign, and appears to have also paid tribute to the Mitanni Empire. The Assyrian monarchy survived, and the Mitannian influence appears to have been short lived.

They appear not to have been always willing or indeed able to interfere in Assyrian internal and international affairs. Ashur-bel-nisheshu (1417–1409 BC) seems to have been independent of Mitannian influence, as evidenced by his signing a mutually beneficial treaty with Karaindash, the Kassite king of Babylonia in the late 15th century. He also undertook extensive rebuilding work in Ashur itself, and Assyria appears to have redeveloped its former highly sophisticated financial and economic systems during his reign. Ashur-rim-nisheshu (1408–1401 BC) also undertook building work, strengthening the city walls of the capital. Ashur-nadin-ahhe II (1400–1393 BC) also received a tribute of gold and diplomatic overtures from Egypt, probably in an attempt to gain Assyrian military support against Egypt's Mitannian and Hittite rivals in the region. However, the Assyrian king appears not to have been in a strong enough position to challenge Mitanni or the Hittites.

Eriba-Adad I (1392–1366 BC), a son of Ashur-bel-nisheshu, ascended the throne in 1392 BC and finally broke the ties to the Mitanni Empire, and instead began to exert Assyrian influence on the Mitanni.

Early Christian period

Syriac Christianity took hold amongst the Assyrians between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD with the founding in Assyria of the Church of the East together with Syriac literature.

The first division between Syriac Christians occurred in the 5th century, when Upper Mesopotamian based Assyrian Christians of the Sassanid Persian Empire were separated from those in The Levant over the Nestorian Schism. This split owed just as much to the politics of the day as it did to theological orthodoxy. Ctesiphon, which was at the time the Sassanid capital, eventually became the capital of the Church of the East. During the Christian era Nuhadra became an eparchy within the Assyrian Church of the East metropolitanate of Ḥadyab (Erbil).[10]

After the Council of Chalcedon in 451, many Syriac Christians within the Roman Empire rebelled against its decisions. The Patriarchate of Antioch was then divided between a Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian communion. The Chalcedonians were often labelled 'Melkites' (Emperor's Party), while their opponents were labelled as Monophysites (those who believe in the one rather than two natures of Christ) and Jacobites (after Jacob Baradaeus). The Maronite Church found itself caught between the two, but claims to have always remained faithful to the Catholic Church and in communion with the bishop of Rome, the Pope.[11]

Middle Ages

Both Syriac Christianity and the Eastern Aramaic language came under pressure following the Arab Islamic conquest of Mesopotamia in the 7th century, and Assyrian Christians throughout the Middle Ages were subjected to Arabizing superstrate influence. The Assyrians suffered a significant persecution with the religiously motivated large scale massacres conducted by the Muslim Turco-Mongol ruler Tamurlane in the 14th century AD. It was from this time that the ancient city of Assur was abandoned by Assyrians, and Assyrians were reduced to a minority within their ancient homeland.[12]

A Schism occurred in 1552 AD, when a number of Assyrian Christians entered communion with the Roman Catholic Church, which, after initially naming their new followers The Church of Assyria and Mosul, coined the term Chaldean Catholic in 1683 AD, giving rise to the modern Chaldean Catholic Church by 1830 AD. This term is purely theological however, the Assyrian Chaldean Catholics having no historical, ethnic, cultural or geographic link to the ancient inhabitants of Chaldea in south east Mesopotamia, who had disappeared into the native population of Babylonia by the 6th century BC.[13]

Upper Mesopotamia had an established structure of dioceses by AD 500 following the introduction of Christianity from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD.[14] After the fall of the Neo Assyrian Empire by 605 BC Assyria remained an entity for over 1200 years under Babylonian, Achamaenid Persian, Seleucid Greek, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid Persian rule. It was only after the Arab-Islamic conquest of the second half of the 7th century AD that Assyria as a named region was dissolved.

The mountainous region of the Assyrian homeland, Barwari, was part of the diocese of Beth Nuhadra (current day Dohuk) since antiquities and have seen a mass migration of Nestorians after the fall of Baghdad in 1258 and Timurlane's invasion from central Iraq.[15] Its Christian inhabitants were little affected by the Ottoman conquests, however starting from the 19th century Kurdish Emirs sought to expand their territories at their expense. In the 1830s Muhammad Rawanduzi, the Emir of Soran, tried to forcibly add the region to his dominion pillaging many Assyrian villages. Bedr Khan Beg of Bohtan renewed attacks on the region in the 1840s, killing tens of thousands of Assyrians in Barwari and Hakkari before being ultimately defeated by the Ottomans.[16]

Early modern period

Peutinger's map of the inhabited world known to the Roman geographers depicts Singara as located west of the Trogoditi. Persi. (Template:Lang-la, "Persian troglodytes") who inhabited the territory around Mount Sinjar. By the medieval Arabs, most of the plain was reckoned as part of the province of Diyār Rabīʿa, the "abode of the Rabīʿa" tribe. The plain was the site of the determination of the degree by al-Khwārizmī and other astronomers during the reign of the caliph al-Mamun.[17] Sinjar boasted a famous Assyrian cathedral in the 8th century.[18]

Syria and Upper Mesopotamia became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, following the conquests of Suleiman the Magnificent.

Modern period

During World War I the Assyrians suffered the Assyrian Genocide which reduced their numbers by up to two thirds. Subsequent to this, they entered the war on the side of the British and Russians. After World War I, the Assyrian homeland was divided between the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, which would become the Kingdom of Iraq in 1932, and the French Mandate of Syria which would become the Syrian Arab Republic in 1944.[19][20][21][22]

Assyrians faced reprisals under the Hashemite monarchy for co-operating with the British during the years after World War I, and many fled to the West. The Patriarch Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII, though born into the line of Patriarchs at Qochanis, was educated in Britain. For a time he sought a homeland for the Assyrians in Iraq but was forced to take refuge in Cyprus in 1933, later moving to Chicago, Illinois, and finally settling near San Francisco, California.[23]

The Assyrian Chaldean Christian community was less numerous and vociferous at the time of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, and did not play a major role in the British rule of the country. However, with the exodus of Assyrian Church of the East members, the Chaldean Catholic Church became the largest non-Muslim religious denomination in Iraq, and some Assyrian Catholics later rose to power in the Ba'ath Party government, the most prominent being Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz. The Assyrians of Dohuk boast one of the largest churches in the region named the Mar Marsi Cathedral, and is the center of an Eparchy. Tens of thousands of Yazidi and Assyrian Christian refugees live in the city as well due to the ISIS invasion of Iraq in 2014 and the subsequent Fall of Mosul [24]

In addition to the Assyrian population, an Aramaic speaking Jewish population existed in the region for thousands of years, living mainly in Barwari, Zakho and Alqosh. However, All of the Barwari Jews either left or were exiled to Israel shortly after its independence in 1947. The region was heavily affected by the Kurdish uprisings during the 1950s and 60s and was largely depopulated during the Al-Anfal campaign in the 1980s, although some of its population later returned and their homes were subsequently rebuilt.[25] Assur, which is in the Saladin Governorate, was put on UNESCO's List of World Heritage in danger in 2003, at which time the site was threatened by a looming large-scale dam project that would have submerged the ancient archaeological site.[26]

Attacks on Christians

Following the concerted attacks on Assyrian Christians in Iraq, especially highlighted by the Sunday, August 1, 2004 simultaneous bombing of six Churches (Baghdad and Mosul) and subsequent bombing of nearly thirty other churches throughout the country, Assyrian leadership, internally and externally, began to regard the Nineveh Plain as the location where security for Christians may be possible. Schools especially received much attention in this area and in Kurdish areas where Assyrian concentrated population lives. In addition, agriculture and medical clinics received financial help from the Assyrian diaspora.[27]

As attacks on Christians increased in Basra, Baghdad, Ramadi and smaller towns. more families turned northward to the extended family holdings in the Nineveh Plain. This place of refuge remains underfunded and gravely lacking in infrastructure to aid the ever-increasing internally displaced people population. In February 2010, the attacks against Assyrians in Mosul forced 4,300 Assyrians to flee to the Nineveh plains where there is an Assyrian-majority population.[28] From 2012, it also began receiving influxes of Assyrians from Syria owing to the civil war there.[29][30]

In August 2014 nearly all of the non-Sunni inhabitants of the southern regions of the Plains, which include Tel Keppe, Bakhdida, Bartella and Karamlish were driven out by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant during the 2014 Northern Iraq offensive.[31][32] Upon entering the town, ISIS looted the homes, and removed the crosses and other religious objects from the churches. The Christian cemetery in the town was also later destroyed.[33] Assyrian Bronze Age and Iron Age monuments and archaeological sites, as well as numerous Assyrian churches and monasteries have been systematically vandalised and destroyed by ISIL. These include the ruins of Nineveh, Kalhu (Nimrud, Assur, Dur-Sharrukin and Hatra).[34][35] ISIL destroyed a 3,000 year-old Ziggurat. ISIL destroyed Virgin Mary Church, in 2015 St. Markourkas Church was destroyed and the cemetery was bulldozed.[36]

Soon after the beginning of the Battle of Mosul Iraqi troops advanced on Tel Keppe, but the fighting continued into 2017.[37][38] Iraqi forces recaptured the town from ISIS on the 19th of January 2017.[27]

Geography

The Assyrian homeland is moderately elevated, being around 200 metres (656 feet) at the south in the Nineveh plains near Mosul, to around 1,900 metres (6,234 feet) in the northern periphery at the highest peaks, just above Zakho. The lower lands include plains, meadow grasses and rolling hills, which are predominantly located to the south and would feature sprawling sclerophyllous scrubland.

So-named, the Nineveh Plains have a topography that's made up of relatively flat, fertile plains which lie on the foothills of the surrounding, rather forested, mountains. Rivers in the region include the Tigris and Euphrates. Parts of them are situated in a riverine forest, and therefore would assist irrigation.[39]

Flora and fauna

Due to its relatively wet climate, plant species would include firs, oaks, conifers, platanus, willow, olive trees, poplar, hawthorn, oriental plane, cherry plum, rose hips, pistachio trees, rosaceae, pear, mountain ash poplar, which are also present in other areas of the autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan region. The desert in the south is mostly steppe and would thus feature xeric species such as, palm trees, tamarix, date palm, fraxinus, poa, white wormwood and chenopodiaceae.[40]

Animals in the region include the Syrian brown bear, wild boar, gray wolf, the golden jackal, Indian crested porcupine, the red fox, goitered gazelle, Eurasian otter, striped hyena, Persian fallow deer, onager, mangar and the Euphrates softshell turtle.[41] Bird species found in the region include, the Dead Sea sparrow, eastern rock nuthatch, European nightjar, hooded crow, masked shrike, Menetries's warbler, pale rockfinch, rufous-tailed scrub robin, see-see partridge and squacco heron, among others.[42]

Climate

Owing to its latitude and altitude, the Assyrian homeland is cooler and much wetter than the rest of Iraq. Most areas in the region fall within the Mediterranean climate zone (Csa), with areas to the southwest being semi-arid (BSh).[43] Summers are very hot for worldwide standards, with average temperatures ranging from 36 °C (97 °F) in the northernmost areas to scorching 40 °C (104 °F) in the southwest, with lows averaging around 21 °C (70 °F) to 24 °C (75 °F). Winters are strikingly cooler and wetter than other regions in Iraq with highs averaging between 9 °C (48 °F) and 11 °C (52 °F) and lows hovering around 3 °C (37 °F). At times, temperatures would occasionally reach freezing, plummeting to −2 °C (28 °F), providing frost and the occasional snowfall. Spring is fairly mild and damp. Autumn is warm and mostly dry.

| Climate data for Tel Keppe | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

14 (57) |

20 (68) |

26 (79) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

43 (109) |

40 (104) |

38 (100) |

30 (86) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

27 (81) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

13 (55) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39 (1.5) |

69 (2.7) |

51 (2.0) |

9 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (0.2) |

36 (1.4) |

60 (2.4) |

270 (10.6) |

| Average precipitation days | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 65 |

| Source: World Weather Online (2000-2012)[44] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Zakho | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

36.2 (97.2) |

40.4 (104.7) |

40.0 (104.0) |

35.7 (96.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

25.1 (77.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 144 (5.7) |

136 (5.4) |

129 (5.1) |

109 (4.3) |

43 (1.7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

27 (1.1) |

83 (3.3) |

127 (5.0) |

799 (31.6) |

| Source: [45] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Assyrian populations are distributed between the Assyrian homeland and the Assyrian diaspora. There are no official statistics, and estimates vary greatly, between less than one million in the Assyrian homeland,[2] and 3.3 million with the diaspora included,[46] mostly due to the uncertainty of the number of Assyrians in Iraq and Syria. Since the 2003 Iraq War, Iraqi Assyrians have been displaced into Syria in significant but unknown numbers. Since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, Syrian Assyrians have been displaced into Turkey in significant but unknown numbers. The indigenous Assyrian homeland areas are "part of today's northern Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran and northeastern Syria".[1]

The Assyrian communities that are still left in the Assyrian homeland are in Syria (400,000),[47] Iraq (300,000),[48] Iran (20,000),[49][50] and Turkey (15,000–25,100).[49][51][52] Most of the Assyrians living in Syria today, in the Al Hasakah Governorate in villages along the Khabur river, descend from refugees that arrived there after the Assyrian Genocide and Simele massacre of the 1910s and 30s. Christian communities of Oriental Orthodox Syriacs lived in Tur Abdin, an area in Southeastern Turkey, Nestorian Assyrians lived in the Hakkari Mountains, which straddles the border of northern Iraq and Southern Turkey, as well as the Urmia Plain, an area located on the western bank of Lake Urmia, and Chaldean and Syriac Catholics lived in the Nineveh Plains, an area located in Northern Iraq.[53]

More than half of Iraqi Christians have fled to neighbouring countries since the start of the Iraq War, and many have not returned, although a number are migrating back to the traditional Assyrian homeland in the Kurdish Autonomous region.[54][55] Most Assyrians nowadays live in northern Iraq, with the community in Northern (Turkish) Hakkari being completely decimated, and the ones in Tur Abdin and Urmia Plain are largely depopulated. Therefore, The area with the greatest concentration of Assyrians on earth is located in Northern Iraq in the Assyrian Triangle, a region which comprises the Nineveh plains, southern Hakkari and the Barwari regions.[3]

Other ethnic groups that live in the region are Arabs, Kurds, Shabaks, Armenians, Yazidis, Mandeans, Kawliya/Roma, Circassians and Turkmen, and historically, there was a significant Iraqi Jewish population until the mid-20th century CE.

Economy

The Nineveh Plain appears to hold under its rich agricultural lands an extension of the petroleum fields tapped in 2006 by the Kurdish Regional Government in direct contract with foreign oil exploration companies. It is believed that this added incentive for absorption by the KRG of the region may lead to economic conflict with Sunni Arab tribes in the Mosul region itself. Assyrians claim that without Nineveh Plain autonomous administration, the indigenous Assyrian presence in its ancient homeland could well disappear. There are some oil reserves in Nineveh Plains.[56]

Most of the inhabitants have practiced dry agriculture since ancient times and rely on the fertile plains to the south, growing agricultural products like grain, wheat, beans and in the summer goods such as cantaloupe and cucumber. Farmers followed old non-technological methods in their farming for several centuries, and their livelihood was always threatened due to nature's betrayal in situations of drought or plant epidemics such as grasshoppers. Besides farmlands, other agriculture also occurs in grape vineyards. Grapevines spread all over the village and produce various types of grapes, among which are the black grapes that are well known in northern Iraq.

Modern agricultural machinery such as tractors, harvester-threshers (reapers), along with new methods of treating and curing plant epidemics now exist. However, irrigation is still a problem in the area, and farming still relies on rainfall. Currently, dozen of farms now belong to the government and are deputized to their owners to use them, as most were taken during Saddam Hussein's control. The Assyrian settlement of Alqosh enjoyed being an important trade center for the various Kurdish, Yazidi, and Arab villages in the region and it houses a large market that receiving agricultural and animal products from across the region.[57]

Creation of an Assyrian autonomous province

The Assyrian-inhabited towns and villages on the Nineveh Plain form a concentration of those belonging to Syriac Christian traditions, and since this area is the ancient home of the Assyrian empire through which the Assyrian people trace their cultural heritage, the Nineveh Plain is the area on which an effort to form an autonomous Assyrian entity has become concentrated. There have been calls by some politicians inside and outside Iraq to create an autonomous region for Assyrian Christians in this area.[58][59]

In the Transitional Administrative Law adopted in March 2004 in Baghdad, not only were provisions made for the preservation of Assyrian culture through education and media, but a provision for an administrative unit also was accepted. Article 125 in Iraq's Constitution states that: "This Constitution shall guarantee the administrative, political, cultural, and educational rights of the various nationalities, such as Turkomen, Chaldeans, Assyrians, and all other constituents, and this shall be regulated by law."[60][61]

Since the towns and villages on the Nineveh Plain form a concentration of those belonging to Syriac Christian traditions, and since this area is the ancient home of the Assyrian empire through which these people trace their cultural heritage, the Nineveh Plain is the area on which the effort to form an autonomous Assyrian entity have become concentrated.

The same article has been used to proclaim an autonomous province for the Yezidi people.[62]

On January 21, 2014, the Iraqi government had declared that Nineveh Plains would become a new province, which would serve as a safe haven for Assyrians.[63] After the liberation of the Nineveh Plain from ISIL between 2016/17, all Assyrian political parties called on the European Union and UN Security Council for the creation of an Assyrian self-administered province in the Nineveh Plain.[64]

Between the 28th-30 June 2017, a conference was held in Brussels dubbed, The Future for Christians in Iraq.[65] The conference was organised by the European People's Party and had participants extending from Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac organizations, including representatives from the Iraqi government and the KRG. The conference was boycotted by the Assyrian Democratic Movement, Sons of Mesopotamia, Assyrian Patriotic Party, Chaldean Catholic Church and Assyrian Church of the East. A position paper was signed by the remaining political organizations involved.[66]

See also

- Assyrian continuity

- Assyrian diaspora

- Assyrian genocide

- Assyrian people

- Beth Nahrain

- Hakkari

- List of Assyrian settlements

- Nineveh plains

- Persian Assyria

- Tur Abdin

- Upper Mesopotamia

- Asōristān

References

- ^ a b c Donabed, Sargon (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8605-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Carl Skutsch (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-135-19388-1.

- ^ a b The Origins of War: From the Stone Age to Alexander the Great By Arther Ferrill – p. 70

- ^ Minorities in the Middle East: a history of struggle and self-expression By Mordechai Nisan

- ^ Frederick Mario Fales (2010). "Production and Consumption at Dūr-Katlimmu: A Survey of the Evidence". In Hartmut Kühne (ed.). Dūr-Katlimmu 2008 and beyond. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 82.

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie (1993). "Nineveh After 612 BC." Alt-Orientanlische Forshchungen 20. P.134.

- ^ Y Odisho, George (1998). The sound system of modern Assyrian (Neo-Aramaic). Harrowitz. p. 8. ISBN 3-447-02744-4.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Albert Kirk Grayson 1972 108was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Poebel, Arno (1942). The Assyrian King List from Khorsabad, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 1/3, 253.

- ^ Parpola, Simo. "ASSYRIAN IDENTITY IN ANCIENT TIMES AND TODAY" (PDF).

- ^ Fuller, 1864, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Hill, Henry, ed (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto, Canada. pp. 108–109

- ^ "History of Ashur". Assur.de. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia during World War I By David Gaunt – p. 9, map p. 10.

- ^ Islamic desk reference, E. J. van Donzel

- ^ A modern history of the Kurds, David McDowall

- ^ Abul Fazl-i-Ạllámí (1894), "Description of the Earth", The Áin I Akbarí, vol. Vol. III, Translated by H.S. Jarrett, Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press for the Asiatic Society of Bengal, p. 25–27

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help). - ^ A short history of Syriac literature. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ David Gaunt, "The Assyrian Genocide of 1915", Assyrian Genocide Research Center, 2009

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 978-1-4008-4184-4. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Genocide Scholars Association Officially Recognizes Assyrian Greek Genocides. 16 December 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-02

- ^ Khosoreva, Anahit. "The Assyrian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire and Adjacent Territories" in The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007, pp. 267–274. ISBN 1-4128-0619-4.

- ^ Travis, Hannibal. "Native Christians Massacred: The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians During World War I." Genocide Studies and Prevention, Vol. 1, No. 3, December 2006.

- ^ "Mar Narsi church – Dhouk". www.ishtartv.com.

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (16 June 2018). "The Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Barwar". BRILL – via Google Books.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Ashur (Qal'at Sherqat)". whc.unesco.org.

- ^ a b Griffis, Margaret (19 January 2017). "Militants Execute Civilians in Mosul; 101 Killed Across Iraq". Antiwar.com. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ UN report.[which?]

- ^ "Relief Projects - Assyrian Aid Society - Iraq". www.assyrianaidiraq.org.

- ^ "{title}". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chulov, Martin; Hawramy, Fazel (9 August 2014). "'Isis has shattered the ancient ties that bound Iraq's minorities'". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E.; Sparshott, Jeffrey; Malas, Nour (8 August 2014). "Barack Obama Approves Airstrikes on Iraq, Airdrops Aid" – via online.wsj.com.

- ^ "Aiding the Assyrians Fight Against ISIS". The Huffington Post. 2015-04-15. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- ^ "ISIL video shows destruction of Mosul artefacts", Al Jazeera, 27 Feb 2015

- ^ Buchanan, Rose Troup and Saul, Heather (25 February 2015) Isis burns thousands of books and rare manuscripts from Mosul's libraries The Independent

- ^ "Assyrian Militia in Iraq Battles Against ISIS for Homeland". www.aina.org. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- ^ Alkhshali, Hamdi; Smith-Spark, Laura; Lister, Tim (22 October 2016). "ISIS kills hundreds in Mosul area, source says". CNN. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Iraqi residents flee Islamic State-held town of Tel Keyf". YouTube. Reuters. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ A Dictionary of Scripture Geography, p 57, by John Miles, 486 pages, Published 1846, Original from Harvard University

- ^ Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra, by A.M.T Moore, G.C. Hillman and A.J Legge, Published 2000, Oxford University Press

- ^ "Iraq's Marshes Show Progress toward Recovery". Wildlife Extra. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Al-Sheikhly, O.F.; and Nader, I.A. (2013). The Status of the Iraq Smooth-coated Otter Lutrogale perspicillata maxwelli Hayman 1956 and Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra Linnaeus 1758 in Iraq. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 30(1).

- ^ "Shaqlawa". Ishtar Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Tel Kaif, Ninawa Monthly Climate Average, Iraq". World Weather Online. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ "Climate: zakho". Climate-Data. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ "UNPO: Assyria". www.unpo.org.

- ^ "Syria's Assyrians threatened by extremists – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "مسؤول مسيحي : عدد المسيحيين في العراق تراجع الى ثلاثمائة الف". Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Ishtar: Documenting The Crisis In The Assyrian Iranian Community". aina.org.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2010-10-13). "Iran: Last of the Assyrians". Refworld. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld – World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Turkey : Assyrians". Refworld.

- ^ Joshua Project. "Assyrian in Turkey". Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Rev. W.A. Wigram (1929). The Assyrians and Their Neighbours. London.

- ^ Assyria. UNPO (2008-03-25). Retrieved on 2013-12-08.

- ^ Paul Schemm (2009-05-15). "In Iraq, an Exodus of Christians". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2011-04-29. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Christian Leaders Unhappy with Lack of Action on Nineveh Plain". www.religiousfreedomcoalition.org.

- ^ "Kurdistan's Gushing Crude Spawns Conflict".

- ^ Iraqi Christians hold critical meeting Archived 2011-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, The Kurdish Globe

- ^ Dutch MP calls for autonomous Assyrian Christian region in north Iraq, AKI

- ^ "{title}" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-14. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Iraq Sustainable Democracy Project". Iraqdemocracyproject.org. 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "Shengal Constituent Assembly Our People Demand To Govern Themselves" ANF - English http://anfenglish.com/kurdistan/shengal-constituent-assembly-our-people-demand-to-govern-themselves

- ^ BetBasoo, Peter; Nuri Kino (22 January 2014). "Will a Province for Assyrians Stop Their Exodus From Iraq?". Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "Iraqi Christians ask EU to support the creation of a Nineveh Plain Province".

- ^ "christians-in-iraq". christians-in-iraq.

- ^ "The Future of the Nineveh Plain - Government - Politics". Scribd.