Greek cruiser Georgios Averof: Difference between revisions

Seaofwords1 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 173: | Line 173: | ||

*{{cite book|last=Campbell|first=John|title=Naval Weapons of World War II|year=1985|publisher=Naval Institute Press|location=Annapolis, Maryland|isbn=0-87021-459-4}} |

*{{cite book|last=Campbell|first=John|title=Naval Weapons of World War II|year=1985|publisher=Naval Institute Press|location=Annapolis, Maryland|isbn=0-87021-459-4}} |

||

*{{cite book|last=Carr|first=John C.|title=R.N.H.S. Averof: Thunder in the Aegean|year=2014|publisher=Pen and Sword Maritime|location=Barnsley, UK|isbn=978-1-47383963-2}} |

*{{cite book|last=Carr|first=John C.|title=R.N.H.S. Averof: Thunder in the Aegean|year=2014|publisher=Pen and Sword Maritime|location=Barnsley, UK|isbn=978-1-47383963-2}} |

||

* Fotakis, Zisis, "The Armoured Cruiser ''Georgios Averof'' (1910)" in Bruce Taylor (editor), ''The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World's Navies, 1880–1990''. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2018. {{ISBN|0870219065}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Fraccaroli|first=Aldo |title=Italian Warships of World War I|location=London|publisher=Ian Allan|year=1970|isbn=0-7110-0105-7}} |

*{{cite book|last=Fraccaroli|first=Aldo |title=Italian Warships of World War I|location=London|publisher=Ian Allan|year=1970|isbn=0-7110-0105-7}} |

||

* |

*{{cite book|last=Friedman|first=Norman|title=Naval Weapons of World War One|publisher=Seaforth|location=Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK|year=2011|isbn=978-1-84832-100-7}} |

||

*{{cite book|editor1-last=Gardiner|editor1-first=Robert|editor2-last=Gray|editor2-first=Randal|title=Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921|year=1985|location=Annapolis|publisher=Naval Institute Press|isbn=0-87021-907-3|lastauthoramp=y}} |

*{{cite book|editor1-last=Gardiner|editor1-first=Robert|editor2-last=Gray|editor2-first=Randal|title=Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921|year=1985|location=Annapolis|publisher=Naval Institute Press|isbn=0-87021-907-3|lastauthoramp=y}} |

||

*{{cite journal |last1=Grazioli |first1=Luciano |title=The Armored Cruiser Averof |journal=Warship International |date=1988 |volume=XXV |issue=4 |pages=370–374 |issn=0043-0374}} |

*{{cite journal |last1=Grazioli |first1=Luciano |title=The Armored Cruiser Averof |journal=Warship International |date=1988 |volume=XXV |issue=4 |pages=370–374 |issn=0043-0374}} |

||

Revision as of 04:36, 8 December 2019

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

37°56′02″N 23°41′01″E / 37.93389°N 23.68361°E

Georgios Averof as a floating museum in Palaio Faliro, Athens

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake | George Averoff |

| Builder | Cantiere navale fratelli Orlando, Livorno |

| Laid down | 1907 |

| Launched | 12 March 1910 |

| Commissioned | 16 May 1911 |

| Decommissioned | 1 August 1952 |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Status | Ceremonially commissioned; Museum ship |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- armored cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 140.13 m (459.7 ft) |

| Beam | 21 m (69 ft) |

| Draft | 7.18 m (23.6 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | |

| Range | 2,480 nmi (4,590 km; 2,850 mi) at 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Georgios Averof (Greek: Θ/Κ Γεώργιος Αβέρωφ) is a modified Template:Sclass- armored cruiser built in Italy for the Royal Hellenic Navy in the first decade of the 20th century. The ship served as the Greek flagship during most of the first half of the century. Although popularly known as a battleship (θωρηκτό) in Greek, she is in fact an armored cruiser (θωρακισμένο καταδρομικό),[1] the only ship of this type still in existence.

The ship was initially ordered by the Italian Regia Marina, but budgetary constraints led Italy to offer it for sale to international customers. With the bequest of the wealthy benefactor George Averoff as down payment, Greece acquired the ship in 1909. Launched in 1910, Averof arrived in Greece in September 1911. The most modern warship in the Aegean at the time, she served as the flagship of admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis in the First Balkan War, and played a major role in the establishment of Greek predominance over the Ottoman Navy and the incorporation of many Aegean islands to Greece.

The ship continued to serve in World War I, the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, and the interwar period, receiving a modernization in France in 1925 to 1927. Following the German invasion of Greece in April 1941, Averof participated in the exodus of the Greek fleet to Egypt. Hopelessly obsolete and prone to mechanical breakdowns, she nevertheless spent the next three years as a convoy escort and guard ship in the Indian Ocean and at the Suez Canal. In October 1944, she carried the Greek government in exile back to liberated Athens, after the withdrawal of the German army.

In 1952, she was decommissioned, before being moved to Poros, where she was berthed from 1956 to 1983. From 1984 until today, she has been reinstated on active duty as museum ship in the Naval Tradition Park in Faliro. After maintenance in late 2017, she achieved seaworthiness state once again, allowing the ship to sail (towed) accompanied by Greek frigate Kountouriotis (F-462) (Φ/Γ Κουντουριώτης) to Thessaloniki Greece where she received more than 130,000 visitors over her 53-day stay.

History

Construction and arrival in Greece

At the beginning of the 20th century, Greece decided to reinforce its fleet, whose ships were fast becoming obsolete due to the rapidly advancing naval technology of the era. The navy procured eight destroyers (then a relatively new type of ship) between 1905–1907, but the most important addition was the armored cruiser Georgios Averof. Like her Italian sisters Amalfi and Pisa, she was being built at Orlando Shipyards, Livorno, Italy. When the Italian government cancelled the third ship of the class due to budgetary concerns, the Greek government immediately stepped in and bought her with a one-third downpayment (ca. 300,000 gold pound sterling), the bequest of a wealthy Greek benefactor, Georgios Averof, whose name she consequently received.

The Averof was fitted with a combination of Italian engines, French boilers, British guns, and German generators.[2] The most discernible difference between the cruiser and her Italian sisters was the shape of her six gun turrets. The Averof encased her British-built guns in rounded pillbox-form housings with convex roof plates. She was also fitted with a foremast, which her sister-ships did not receive until after the start of the First World War. Such was the urgency of the Greek Navy to see the ship in service, that they accepted her with a gouge inside one of the 7.5-inch (191 mm) gun barrels. This had been caused by the slip of a rifling tool, but Armstrong Whitworth's chief ordnance engineer correctly judged the defect as inconsequential to the weapon's performance and safety.

The Averof was launched on 12 March 1910. She would be the last commissioned armored cruiser in the world, a class of warship that had already been rendered obsolete by the battlecruiser. Her first captain, Ioannis Damianos, took command on 16 May 1911, and the Averof immediately sailed to England for the Coronation Naval Review of King George V. While there, she would also receive the first load of ammunition for her British-built guns. The stay in England was troubled by running aground at Spithead on 19 June, which forced her into drydock. While waiting for repairs, her crew was involved in a large brawl with the locals, caused by their unfamiliarity with the mould found on edible blue cheese. Captain Damianos was deemed inadequate to maintain discipline, and replaced by the esteemed taskmaster, Pavlos Kountouriotis. During the journey home, Captain Kountouriotis thoroughly trained his crew, with the exception of gunnery practice, as ammunition was limited to special deliveries from Britain. The Averof finally reached Faliro Bay, near Athens, on 1 September 1911. At that time, she was the most modern and powerful warship in the navies of the Balkan League or the Ottoman Empire.

Balkan Wars

With the outbreak of the First Balkan War in October 1912, Kountouriotis was named rear admiral and commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Royal Navy. Averof, under Captain Sofoklis Dousmanis, served as the flagship of the fleet, and she took part in the takeover of the islands of the northern and eastern Aegean. During the naval battles at Elli (3 December 1912) and Lemnos (5 January 1913) against the Ottoman Navy, she almost single-handedly secured victory and the undisputed control of the Aegean Sea for Greece. In both battles, due to her superior speed, armor and armament, she left the battle line and pursued the Turkish Fleet alone. During the Battle of Elli, Kountouriotis, frustrated by the slow speed of the three older Greek battleships, hoisted the Flag Signal for the letter Z which stood for "Independent Action", and sailed forward alone, with a speed of 20 knots (37 km/h) against the Turkish fleet. Averof succeeded in crossing the T of the Turkish fleet and concentrated her fire against the Ottoman flagship, thus forcing the Ottoman fleet to retreat in disorder. Likewise, during the Battle of Lemnos, when the older battleships failed to follow up with Averof, Kountouriotis did not hesitate to pursue independent action.

In each battle the ship suffered only slight damage, while inflicting severe damage to several Turkish ships. These exploits propelled her and her Admiral to legendary status in Greece. After the Battle of Lemnos, the crew of Averof affectionately nicknamed her "Lucky Uncle George". It is a notable fact that, due to the aforementioned need to conserve ammunition which had to be secured from Britain, Averof fired her guns for the first time during the Battle of Elli.

Georgios Averof is credited with successfully closing the Aegean Sea to Ottoman transports bringing fresh troops and supplies to the front during the First Balkan War. This success had a concrete impact on the land action where the Ottoman forces suffered decisive defeats. It is hypothesized that in the lack of such decisive control of the sea by the Greek Navy, the Ottoman Empire might have reinforced its forces on the Balkan Peninsula and therefore fared better in the war.[3]

World War I and aftermath

During World War I, Averof did not see much active service, as Greece was neutral during the first years of the war, and in deep internal turmoil (see National Schism). After the Noemvriana riots of 1916, she was seized by the French, and only returned after Greece formally entered the war on the side of the Allies in June 1917. After the armistice, Averof sailed with other Allied warships to Constantinople, where she received an ecstatic welcome from the city's many Greeks. Under Rear Admiral Ioannis Ipitis, the cruiser continued to serve as flagship of the Royal Hellenic Navy. During the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), she supported troop landings in Eastern Thrace, bombarded the Turkish Black Sea coastline, and helped to evacuate refugees after the Greek Army's defeat.

From 1925 to 1927, the cruiser underwent a major refit in France, during which she received modern anti-aircraft armament, a new tripod-foremast and conning tower, improved fire-control equipment, and an overhaul of her engines, boilers, and furnaces. The ship's obsolete 17-inch torpedo tubes were also removed. Given her age, the cost of converting the vessel to fuel-oil firing was considered prohibitive. On 20 May 1937, Averof joined the warships of fourteen other nations at the Coronation Naval Review in Spithead, England. She was the only one of the 150 vessels present which had also attended the previous coronation review in 1911. King George VI was reminded of the fact, as he warmly welcomed Averof's captain, during the preliminary introduction of Britain's naval guests.

World War II and aftermath

In the early morning of 18 April 1941, after the collapse of the Greco-German front, the Averof's crew disobeyed direct orders to scuttle the ship in preventing her possible capture by the enemy. They cut through a closed harbor-boom with axes and handsaws to let the vessel escape, and their commanding officer dramatically embarked up a rope ladder to join them as the vessel was underway. Under the constant threat of Luftwaffe air strikes (which had sunk many Greek and British warships during the evacuation), the cruiser sailed to Souda Bay, Crete. Then on to the UK naval station at Alexandria, arriving in Egypt on 23 April.

While too slow to serve with the British Fleet in the Mediterranean, and also lacking sufficient anti-aircraft armament for that theatre of operation, the old armored cruiser was considered quite appropriate for escorting Indian Ocean convoys. In this capacity, she could offer more firepower than a contemporary heavy cruiser (albeit with less gunnery range), and twice their respective armour protection, quite sufficient to deal with the threat posed by German raiders operating in the sector. This task also required no more speed than her then greatly reduced maximum of 12 knots. So from September 1941 through October 1942, under British control, she was assigned to convoy escort and patrol duties in the Indian Ocean and based at Bombay.

The Averof left Alexandria on 30 June and passed through the Suez Canal to Port Tewfiq (Port Suez). The three weeks spent there saw her crew involved in the rescue of sailors and soldiers aboard the Cunard Line troopship MV Georgic, which was set ablaze and sunk at an adjacent berth during a Luftwaffe air raid on 6 July. With several of her boilers deactivated, and the fuel-oil spraying mechanism for her coal furnaces now inoperable, the Averof was then capable of only 9 knots, insufficient for her planned convoy duties. So on 20 July, the ship departed for Port Sudan, where she underwent three weeks of emergency repairs to her oil-accelerant apparatus, raising her cruising speed to the required minimum. The vessel then resumed her passage of the Red Sea and reached the port of Aden, in late-August. From there, she sailed in an unassigned convoy crossing of the Indian Ocean, arriving at Bombay on 10 September 1941.

As the Averof had not seen an overhaul of her boilers and furnaces since 1926, mechanical problems continued to plague the vessel and ultimately cut short her usefulness in convoy service. On 28 September she was assigned to escort an oil tanker convoy (BP.16) from Bombay to Basra in the Persian Gulf, but was detached before completing the voyage due to faulty boilers. This was of extra concern because on 24 September, the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran had sunk the Stamatios G. Embiricos at the equator, ending three months of raider inactivity in the sector. By the time the Averof was forced to leave her convoy, the Greek freighter was already four days overdue to Columbo, Ceylon, meaning the enemy would have had a week to sail in any direction from the Embiricos' last known position. However, the Kormoran had moved southeast towards Australia (and her fateful meeting with HMAS Sydney), and convoy BP.16 reached Basra safely on 5 October. The Averof returned to Bombay on 4 October, where the cruiser underwent emergency repairs. On 20 December, she finally sailed again from Bombay to “cover” a troop-support convoy (BM.31B) headed for Singapore with a stop at Columbo. Here she was detached, returning to Bombay on 5 January 1942.

On 9 January the Averof again put to sea in advance of the unescorted departures of six troopships from Bombay and Karachi, headed for Basra (BP.31A – 31B). The cruiser could not hope to keep up with these vessels, traveling at 14 to 16 knots, so she was once again designated as a patrol vessel (“defensive cover”) for the sea lane in which they would eventually overtake her. Turning in the Gulf of Oman, the Averof's lookout spotted a modern freighter appearing to shadow the warship at a safe distance. The cruiser went to “battle stations” over the possible sighting of a merchant raider, but the suspicious vessel altered course and sped away.

This incident appears to have prompted a call for gunnery practice after the ship returned to Bombay on 15 January. During these exercises in the bay outside the harbor, the recoil from one of the Averof's eight-gun broadsides fractured the mounts on two of her active boilers and sent them crashing to the deck. The vessel limped into port for major repairs and did not venture out again until she departed Bombay in early November 1942. By then, she had been dubbed, “Georgios Never-off”, by the base’s Royal Navy personnel. Again repaired to a cruising capability of 12 knots, she sailed for Port Said, Egypt, in an independent passage of the Arabian and Red Seas, and took up duties as a Suez Canal guard ship from mid-November 1942.

Averof was the only World War I-era armored cruiser to serve in her original capacity during World War II (several old Japanese vessels of the type acted as training ships, or were converted for minelaying). While her 9.2-inch British-built ordnance was no longer in sea service with the Royal Navy, many of these weapons had been moved to coastal batteries and their shells were readily available. The British 7.5-inch naval gun was still employed on three of the Royal Navy's Hawkins-class heavy cruisers, as well as shore installations, so its ammunition also remained in production. However, this was not to prove a factor in Averof's viability, as she was never again required to fire her guns in anger.

On 17 October 1944, once again as the flagship of the exiled Hellenic Navy, and under the command of Captain Theodoros Koundouriotis (the Admiral's son), she carried the Greek government-in-exile from Cairo to liberated Athens. Averof continued as Fleet Headquarters until she was decommissioned in 1952. Afterward, the vessel remained anchored at Salamis until she was towed to Poros, where she was berthed from 1956 to 1983.

Averof as a floating museum

In 1984 the Navy decided to restore her as a museum ship, and in the same year she was towed to Palaio Faliro, where she is anchored as a functioning floating museum, seeking to promote the historical consolidation and upkeep of the Greek naval tradition. Free guided tours are provided to visiting schools and on holidays. In 2016 she has been retrofitted with an internal elevator allowing access to most decks by visitors with movement disabilities. She is berthed at Trocadero quay, as part of the Naval Tradition Park.

The ship is crewed and regarded as in active service, carrying the Rear Admiral's rank flag a square blue flag with white cross, like the Greek jack, with two white stars in each of the two squares on the flagstaff side[4][5] atop the mainmast with the masthead pennant (a long triangular blue flag with a white orthogonal Greek cross) displaced downward. Every Hellenic Navy ship entering or sailing in Faliro Bay honours Averof while passing. The crew are ordered to attention (with the "Still to" order) and from the relevant boatswain's pipe (or bugle call) every man on decks stands to attention, officers saluting, looking to the side where Averof is in sight until "Continue" is ordered.[6]

In June 2010 the ship was involved in a scandal after being used as the stage for a lavish wedding party by Greek shipowner Leo Patitsas and TV persona Marietta Chrousala. The publication of photos from the party by the Proto Thema tabloid caused major political uproar, resulting in the dismissal of her commander, Commodore Evangelos Gavalas.[7][8]

On 26 April 2017, the Averof was towed from her museum dock at Palaio Faliro to the Skaramangas Shipyard, in Elefsis. Two commercial tugs and a pilot craft maneuvered the cruiser under the command of the Commodore Sotirios Charalampopoulos. A Greek Navy tug and a helicopter also assisted the operation. At the shipyard, the Averof underwent two months of maintenance and repairs, partially funded by Greek shipping magnate and philanthropist, Alexandros Goulandris. In May 2017, Goulandris, together with Hydra Ecologists Club, and several retired Hellenic Navy officers, announced their intention to begin a thorough review of the mechanical parts that would need to be newly machined or refurbished, so that the ship might eventually sail the Aegean under steam power. If realised, it would make the Averof the oldest operational steel warship in the world. Goulandris died on 25 May 2017, three weeks after the announcement.

Averof sails again

The cruiser's two months of dry dock inspection and hull maintenance were a prelude to the vessel's first voyage in 72 years. On 5 October 2017, the Averof left her long-time berth at Palaio Faliro, and was towed 250 miles across the open sea to a 50-day exhibition-docking on Thessaloniki's urban waterfront. The vessel was escorted by up to six large tugs and a pilot craft from Zouros Salvage & Towage. A Hellenic Navy tugboat also accompanied them. On 7 October, the group approached the Thessaloniki dock with horns and sirens blaring, their fire-fighting nozzles shooting great plumes of water skywards. An honor guard of Greek sailors and a Hellenic Navy band were arrayed along the dock to meet the ship. After 7 weeks of heavy visitation (over 130,000 visitors in 53 days[9]) by the general public, the Averof returned to her Palaio Faliro museum dock on 13 December.

Image gallery

-

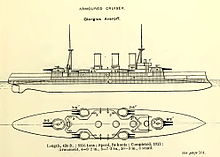

Layout

-

Admiral Kountouriotis with the crew of Averof on the ship's deck

-

A naval band plays under Averof's main guns, shortly before celebrating Independence Day during World War II

-

Lithograph honouring Averof printed after the Balkan Wars

-

Painting depicting Averof in the Bosporus in 1919. Hagia Sophia in the background

-

View of quarterdeck in 2013

References

- ^ However she was usually classified as a battlecruiser after the Washington Naval Treaty (1922) because her displacement and main armament slightly exceeded the limits imposed on cruisers.

- ^ www.bsaverof.com

- ^ Ozturk, Cagri., "For Want of a Horseshoe: Alternate Histories of Turkey That Fared Better in the First Balkan War", paper presented at The Centenary of the Balkan Wars (1912–1913): Contested Stances Conference, 23–24 May 2013, Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2005-11-27. Retrieved 2005-08-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ http://www.pbase.com/drf/image/22944735

- ^ this link Archived 2005-12-20 at the Wayback Machine is an mp3 sound recording of the order in Greek "Still to port side", the boatswain's pipe call and the order "Continue").

- ^ Σάλος για το γαμήλιο πάρτυ Πατίτσα-Χρουσαλά στο θωρηκτό "Αβέρωφ" (in Greek). AlphaTV. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ^ Γαμήλιο πάρτι στο θωρηκτό Αβέρωφ! (in Greek). Naftemporiki. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ^ Μπάρμπα, Βάσια. "Αβέρωφ: Αντίο στη Θεσσαλονίκη με 130.000 επισκέπτες (φωτο+video)". Αβέρωφ: Αντίο στη Θεσσαλονίκη με 130.000 επισκέπτες (φωτο+video). Retrieved 2018-04-18.

Sources

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Carr, John C. (2014). R.N.H.S. Averof: Thunder in the Aegean. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-47383963-2.

- Fotakis, Zisis, "The Armoured Cruiser Georgios Averof (1910)" in Bruce Taylor (editor), The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World's Navies, 1880–1990. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2018. ISBN 0870219065

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0105-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Grazioli, Luciano (1988). "The Armored Cruiser Averof". Warship International. XXV (4): 370–374. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Halpern, Paul S. (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. IV (reprint of 1928 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-253-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918: Navalism, Industrial Development, and the Politics of Dualism. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9. OCLC 59919233.

- Stephenson, Charles (2014). A Box of Sand: The Italo-Ottoman War 1911–1912: The First Land, Sea and Air War. Ticehurst, UK: Tattered Flag Press. ISBN 978-0-9576892-7-5.