Sumitro Djojohadikusumo

Sumitro Djojohadikusumo | |

|---|---|

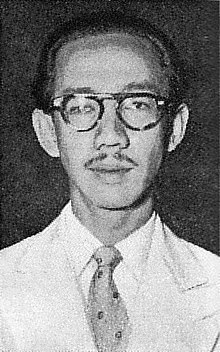

Sumitro in 1954 | |

| 3rd Minister of Research of Indonesia | |

| In office 28 March 1973 – 28 March 1978 | |

| President | Suharto |

| Preceded by | Suhadi Reksowardojo |

| Succeeded by | B. J. Habibie |

| 8th Minister of Finance | |

| In office 3 April 1952 – 30 July 1953 | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Preceded by | Jusuf Wibisono |

| Succeeded by | Ong Eng Die |

| In office 12 August 1955 – 24 March 1956 | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Preceded by | Ong Eng Die |

| Succeeded by | Jusuf Wibisono |

| 7th Minister of Industry and Trade | |

| In office 6 September 1950 – 27 April 1951 | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Preceded by | Tandiono Manu |

| Succeeded by | Sujono Hadinoto |

| In office 6 June 1968 – 28 March 1973 | |

| President | Suharto |

| Preceded by | Mohammad Jusuf |

| Succeeded by | Radius Prawiro |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Soemitro Djojohadikoesoemo 29 May 1917 Kebumen, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 9 March 2001 (aged 83) Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Resting place | Karet Bivak Cemetery |

| Political party | Socialist (PSI) |

| Spouse |

Dora Marie Sigar (m. 1947) |

| Children | 4, including Prabowo Subianto and Hashim Djojohadikusumo |

| Alma mater | Netherlands School of Economics Sorbonne University |

| Occupation | |

| Signature |  |

Sumitro Djojohadikusumo (EVO: Soemitro Djojohadikoesoemo; 29 May 1917 – 9 March 2001) was an Indonesian economist and politician. One of the country's most influential economists, he held notable roles under both presidents Sukarno and Suharto. During his career in government, he served as Minister of Industry and Trade, Minister of Finance, and the Minister of Research. He was also the Dean of the Faculty of Economics at the University of Indonesia.

Born into a Javanese family, Sumitro studied economics at the Netherlands School of Economics. Returning to Indonesia following the conclusion of the Second World War, he was thereafter assigned to the country's diplomatic mission in the United States, where he sought to raise funds and and garner international attention in the struggle against Dutch colonialism. After the handover of sovereignty in the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference, in which he took part, he joined the Socialist Party of Indonesia and became Minister for Trade and Industry in the Natsir Cabinet. He implemented the protectionist Benteng program, and developed an economic plan which aimed for national industrialization. Sumitro served as finance minister in the cabinets of Prime Ministers Wilopo and Burhanuddin Harahap. During the 1950s, Sumitro favoured foreign investment, an unpopular position at that time which brought him into conflict with nationalists and communists.

Due to political differences and allegations of corruption, he fled Jakarta and joined the insurrectionary Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia in the late 1950s. Considered a leader of the movement, Sumitro operated from abroad, liaising with with Western foreign intelligence organizations while seeking funds and international support. After the movement's defeat, Sumitro remained in exile as a vocal critic of Sukarno, continuing to agitate for the downfall of the government. With the establishment of the New Order, Sumitro was invited to return from exile and in 1967 was reappointed Minister of Industry and Trade. In this position, Sumitro set policies favoring industrialization through imports of capital goods and export restrictions of raw materials. He was involved in the high-level planning of Indonesia's economy, along with many of his former students from the University of Indonesia.

After disagreements with Suharto on policy in the early 1970s, Sumitro was first reassigned as Minister of Research before his removal from government posts altogether. Throughout the New Order, Sumitro leveraged his foreign and political connections to establish substantial private business interests and a political presence for his family, with his son Prabowo Subianto joining the military and marrying Suharto's daughter. He also continued to work as an economist with some influence during the 1980s. In the leadup to the 1997 Asian financial crisis he began to call for greater deregulation of the economy, but remained committed to the political structure of the New Order. Following his death, his children and grandchildren remained influential in Indonesian politics.

Early life

Sumitro was born in Kebumen on 29 May 1917, the eldest child of Margono Djojohadikusumo, a high ranking civil servant in the Dutch colonial government and later founder of Bank Negara Indonesia.[1][2] He studied at a Europeesche Lagere School (a school typically serving European children), then an Opleiding School Voor Inlandsche Ambtenaren (a school for indigenous Indonesians going to the civil service) in Banyumas.[3]

After finishing secondary education in 1935, he commenced tertiary studies at the Netherlands School of Economics.[2] Completing his bachelor's in 1937, he then took a one-year course in philosophy and history at the Sorbonne.[2][4] In his biography, Sumitro claimed that he wanted to join the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War and had briefly joined a training camp in Catalonia, but he was rejected due to his age.[5] In a 1986 recollection, Sumitro noted that he continued to fundraise for the Republican cause.[6] During his studies, he joined an Indonesian students' organization there which aimed to promote Indonesian arts and culture.[7]

He was completing his dissertation at Rotterdam in May 1940 when Germany invaded the Netherlands, and during the Rotterdam Blitz he was nearly killed by a Luftwaffe bomb which destroyed one of the walls to his room.[8] He still completed his dissertation, "The People’s Credit Service during the Depression", and earned his doctorate in 1943.[2] This made him the first Indonesian to earn a PhD in economics.[9] During the later stages of the war in Europe, after the conclusion of his studies, he helped provide aid to a number of stranded Indonesian sailors in Rotterdam, as the Perhimpoenan Indonesia association itself took part in the Dutch resistance mostly by distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets.[10] Prior to the war, Sumitro had decided to not join the association due to the presence of communists such as Abdulmadjid Djojoadiningrat.[4] Unable to return to Indonesia during wartime, he spent his time studying the Indonesian economy.[11]

National Revolution

Early Revolution

After the end of the war, Sumitro briefly joined a Dutch delegation in an United Nations Security Council meeting in London on January 1946, before returning to Indonesia in March that year.[12][13] According to British reports, Sumitro had been included in the delegation to provide a good impression for the Dutch government, but Sumitro became disillusioned and decided to return to his home country.[14] Sumitro's brief experience at the Security Council allowed him to share its procedures with other Indonesian nationalists.[15] He joined the new Republican government, becoming an assistant to Prime Minister Sutan Sjahrir and later working at the Ministry of Finance.[16] In the leadup to the 3 July affair in 1946, Sumitro alongside Sjahrir and welfare minister Darmawan Mangunkusumo were kidnapped by disgruntled army units.[17] Still in 1946, he was assigned to the Indonesian delegation to the United Nations in the United States as deputy chief of mission and minister plenipotentiary for economic affairs,[2][18] while he unofficially engaged in fundraising.[19] He would remain in this posting until 1950.[2][18]

Due to the Dutch embargo on Indonesian trade, Sumitro was charged with bypassing it, and in one occasion American cargo ship SS Martin Behrman carrying cargo from the Republican city of Cirebon was seized by Dutch marines. Sumitro had arranged the ship's voyage despite expecting a Dutch seizure, as the delegation calculated that the media attention would be invaluable. The ship's seizure prompted anger from the National Maritime Union and an US congressional investigation was considered, until it was released. Sumitro quoted Sutan Sjahrir as saying "we lost $3 million of cargo, but we couldn't have paid for the public attention".[20] In his time in the United States, Sumitro also signed a contract with American businessman Matthew Fox to form the Indonesian–American corporation, a sole agent for bilateral trade of several commodities between the two countries for 10 years.[21][22]

Diplomatic talks

Following the 1948 Operation Kraai, Sumitro and members of the Indonesian UN delegation (led by L.N. Palar) was vital in maintaining international awareness of the Indonesian situation.[18] While previously the Indonesian delegation had been ignored, the military operation brought Indonesia to the forefront of attention, and after a meeting with Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett, Sumitro gave a press conference which was prominently featured in American media - The New York Times, for example, published in entirety a memorandum from Sumitro condemning Dutch actions and calling for the cessation of American aid (i.e. the Marshall Plan) to the Netherlands.[23][24] Sumitro later briefly headed the Indonesian embassy in the United States.[25]

During the final negotiations on the handover of Indonesian sovereignty Sumitro led the economic and financial subcommittee. In these negotiations, while the Dutch calculated that the Indonesians would have to take on debt passed on from the Dutch East Indies government amounting to over 6 billion guilders, Sumitro argued the opposite - that a significant proportion of the debts were created to fight the Indonesian National Revolution and should not be paid by the Indonesian government, and instead he calculated that the Dutch government would owe the Indonesian one an amount of 500 million guilders. The agreement was eventually struck that the Indonesian government would be responsible for 4.3 billion guilders in debt,[26] to be paid in full by July 1964.[27] Sumitro wanted to negotiate down the debt further, but was overridden by Vice President Mohammad Hatta.[28] Sumitro also opposed the deferral of the Western New Guinea issue, but was again overridden by Hatta.[29]

Cabinet Minister

Minister of Industry

Sumitro was appointed as Minister of Trade and Industry in the newly formed Natsir Cabinet in 1950, as a member of Sutan Sjahrir's Socialist Party of Indonesia (PSI).[30][31][a] Contrary to the views of Finance Minister Sjafruddin Prawiranegara who focused on agricultural development, Sumitro viewed industrialisation as necessary to develop Indonesia's economy. Sumitro introduced the "Economic Urgency Plan" which aimed to restore industrial facilities that had been damaged by the Japanese invasion and the subsequent independence war.[33] The plan, sometimes called the "Sumitro Plan", was published in April 1951 (after the Natsir Cabinet's collapse), and called for the use of government funds to develop a number of industrial facilities across Java and Sumatra. However, none of the planned projects were completed within the two-year timeline of the plan by the succeeding Sukiman and Wilopo Cabinets, and the duration of the plan was extended to three years.[34][35]

During this tenure, he also toured Netherlands and other European countries to secure agreements establishing manufacturing facilities in Indonesia.[36] He initiated the Benteng program, an import control scheme benefitting indigenous Indonesian businessmen at the expense of the Chinese Indonesian mercantile class, despite his own preference for a free market system for imports.[37] After the collapse of the Natsir Cabinet, Sumitro became dean of the economics faculty at the University of Indonesia in 1951, after its first dean Sunarjo Kolopaking had resigned.[38][39] He served in this academic position between 1951 and 1957, and in this position he recruited a number of Dutch academics to fill in the lack of teachers in the faculty. He also founded the Institute of Economic and Social Research (Lembaga Penyelidikan Ekonomi dan Masyarakat), which he would later utilize to form economic policies when he returned to being a government minister. He also arranged for an affiliate program between the faculty and the department of economics at University of California, Berkeley.[38][b]

To diversify the views of Indonesian economists, whose education at that time was still dominated by European curriculum, Sumitro arranged for an exchange program sponsored by the Ford Foundation whereas American professors would teach in Indonesia and Indonesian students would spend several years in the United States.[41] In mid 1951, he also invited Hjalmar Schacht, the former finance minister of Nazi Germany, to Indonesia in order to research the country's economic and financial situation, and to produce a recommendation.[42] Schacht's report called for much increased foreign investment and advisory, directly contrasting with the Indonesian popular mood at the time. Sumitro did not implement these recommendations, however.[43] Additionally, he also took part in efforts to nationalize De Javasche Bank, the colonial central bank.[44] During this lull between his two ministerships, Sumitro also engaged in a public debate with Sjafruddin Prawiranegara, on their differing views on Indonesian economic development while both also criticizing the incumbent Sukiman Cabinet.[45] Sumitro criticized Sjafruddin's priority on agrarian development, citing the poor standard of living in the agrarian economic structure before independence, and also disagreed with Sjafruddin's policy on accumulating capital reserves instead of pursuing an expansionary fiscal policy.[46] The two economists did agree on maintaining foreign investment and capital in Indonesia, in contrast to a number of nationalist leaders at that time.[47] He also wrote in support of the transmigration program, though he noted that industrial development in the migration regions would be needed.[48]

Minister of Finance

In the Wilopo Cabinet, Sumitro was given the office of Minister of Finance.[30][49] When he first joined the ministry, which at that time still included a large number of Dutch officials, he noted how many of them were skilled administrators, but were not qualified in economics.[50] The nationalization of De Javasche Bank and its conversion into Bank Indonesia was completed during his tenure. When drafting the relevant laws Sumitro, incorporated a requirement that all directors of the Bank's board be Indonesian citizens.[51] He also expanded the Benteng program, extending the list of restricted goods from 10 percent of imports to over half.[52] Sumitro himself did not believe that the Benteng program would be perfect in execution, even commenting that a majority of the businessmen given support might turn out to be "parasites".[53]

Following the collapse of the Wilopo Cabinet in 1953, political maneuvering resulted in a number of cabinets failing to be approved. Sumitro was named Minister of Finance in one such proposed cabinet by Burhanuddin Harahap, but his candidacy in particular was vetoed by the Indonesian National Party and eventually the First Ali Sastroamidjojo Cabinet was formed where Sumitro was replaced by Ong Eng Die.[54] In this period, Sumitro as part of the opposition criticized the Ali cabinet's policies, and accused the policies to be an indirect attempt at forcing the capital flight of Dutch firms.[55] He would return to the office of finance minister in 1955, in the Burhanuddin Harahap Cabinet, as one of the few highly-educated and experienced ministers in the cabinet.[56][57] The country faced an issue of high inflation at that time, and it was decided to abolish the Benteng program in order to increase domestic production and stabilize the economy.[58]

Sumitro also implemented fiscal belt-tightening, reducing the government deficit significantly. These policies did result in some reduction in inflation.[59] In the aftermath of the 1955 election, where PSI performed poorly, Sumitro launched an unsuccessful challenge against Sjahrir's leadership of the party.[60][61][c] Several PSI members considered Sumitro's organizational skills preferable to Sjahrir's ideological approach to the party.[62] He was dispatched to Geneva in late 1955 in order to negotiate the issue of Western New Guinea with the Dutch, and despite progress on negotiations thanks to American, British, and Indian pressure on Dutch negotiators, domestic political pressure caused the Indonesian government to withdraw from negotiations in January 1956. The government ministers at Geneva at that time - Sumitro, health minister Johannes Leimena, and foreign minister Ide Anak Agung Gde Agung, all were greatly disappointed by the development and considered resigning from government.[63] In the final months of the cabinet, Sumitro extended government credits to a number of politically affiliated firms, which was seen by many as political patronage and resulted in increased pressure from the opposition to speed up the cabinet's dissolution.[64]

Like other members of the Harahap Cabinet, Ali Sastroamidjojo explicitly excluded Sumitro from joining his second cabinet.[65] Throughout the liberal democracy period, Sumitro had been described as the most powerful PSI government minister.[66] In a 1952 paper, Sumitro indicated the objectives of his policies - to stimulate domestic consumption and investment and improve the trade balance, while commenting that due to the poor administrative capabilities of the Indonesian government it should avoid direct interventions.[67] Sumitro was also a supporter of foreign investment, and in a speech shortly before his first inauguration as finance minister he commented how removing foreign investors would be akin to "digging our own grave".[68] To the small number of foreign companies which did invest in Indonesia during the 1950s - mostly oil companies - Sumitro lobbied for the development of Indonesian human capital, in exchange for a number of fiscal incentives.[69]

PRRI Rebellion

Joining the rebellion

When the Guided Democracy era began in 1957, Sukarno showed his dislike for Western-educated economists such as Sumitro, a position also supported by the Communist Party of Indonesia under D.N. Aidit. Aidit directly accused Sumitro of "siding with imperialism and feudalism", and he argued that Sumitro's economic approach which involved foreign investment did not fit Indonesian rural society. Aidit rejected Sumitro's argument that poverty was caused by low investment and savings, and instead blamed capitalists, landlords, and foreign companies for engaging in rent-seeking behavior.[70] Communists, who already harbored a resentment against PSI and Masyumi since the Madiun Affair in 1948,[71] associated the general open approach to foreign investment to Sumitro.[72] By May 1957, he had been summoned twice under alleged corruption related to PSI's fundraising for the 1955 election,[73] and his links to a businessman who had been jailed for bribery. On 8 May 1957, he was given a third summons.[74] In order to evade the investigation, Sumitro went into hiding - first at a friend's home in Tanah Abang, before he managed to escape to Sumatra with the help of Sjahrir. Throughout 1957, PSI politicians visited Sumitro, unsuccessfully attempting to convince him against joining a potential rebellion, and eventually Sumitro began to avoid the party's members sent for him altogether.[75]

Arriving on 13 May in Central Sumatra,[74] Sumitro found refuge under the Dewan Banteng (Banteng Council) in West Sumatra. As tensions rose between the emerging dissidents in the regions and the civilian government in Jakarta, many of the leaders under Banteng Council, including Sumitro, refused to accept a potential compromise which would involve moderate politicians such as Mohammad Hatta returning to the government.[76] Other leaders, particularly Masyumi leaders such as Sjafruddin Prawiranegara and Burhanuddin Harahap were also in West Sumatra with Sumitro.[77] During this period, Sumitro travelled abroad frequently, making contacts with foreign governments and journalists, and in Singapore he reestablished contact with a CIA agent he had previously met in Jakarta.[74] In September, Sumitro met with a number of dissident colonels, and issued demands to the central government demanding decentralization, replacement of Abdul Haris Nasution in the military, the reappointment of Hatta, and a ban on "internationally oriented communism".[78] By October, Soemitro began corresponding with British and American intelligence agents mainly in Singapore.[79] It was likely that Sumitro's contacts with American agents increased the resolve of the dissident officers.[80] Another meeting of the dissident colonels and politicians had been held in Padang on mid-September, and Sumitro communicated the results of the meeting to the Americans, painting the dissident group as an anti-communist front. Sumitro also stated his plans to finance the movement through the sales of Sumatra's agricultural products to the British.[81]

Rebellion and exile

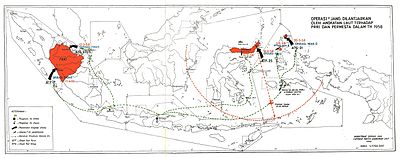

By late 1957, Sumitro was in contact with officials from the United States, Britain, British Malaya, the Philippines, and Thailand, in addition to British, Dutch, and overseas Chinese businesses in order to raise funds for the rebelion.[79] Both foreign aid and revenue from commodity smuggling allowed the rebels to purchase weapons and equipment, with the United States providing enough weapons for thousands of fighters.[82] He participated in another dissident meeting in the town of Sungai Dareh in January 1958, and a deadlock occurred due to the reluctance of South Sumatra's military commander Colonel Barlian to support an open rebellion. Barlian had believed that the other military leaders and Sumitro were pushing for an open confrontation with the central government, and to moderate their pressure, he invited Masyumi leaders to the meeting.[83]

Despite this, Sumitro headed to Europe shortly after the meeting, raising more funds and giving interviews relaying the movements' demands.[83] When Sumitro was in Singapore in late January, the Indonesian government sent a request to British authorities to repatriate him.[84] As he continued to be abroad, Sumitro's media statements became increasingly bellicose, threatening a potential civil war in a 2 February statement from Geneva,[85] then further claiming that should a civil war happen, Sukarno's government "would probably topple within ten days."[86] On the other hand, pro-government press in Jakarta mocked Sumitro's (popularly believed) personal wealth, nicknaming him miljioener kerakjatan ("millionaire of the people"), also a play on the PSI motto Kerakjatan.[84] On 15 February 1958, the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI) was declared in Bukittinggi, in which Sumitro was named as minister of trade and communications, and Sjafruddin was appointed as prime minister.[87] The following day, Sukarno ordered the arrest of PRRI's ministers, including Sumitro.[88] Sumitro was considered one of the primary leaders of PRRI.[89]

The PRRI performed poorly against the Indonesian military, being dislodged from the major cities of Sumatra by mid-1958. Sumitro himself was appointed by Sjafruddin as acting foreign minister, to be based in Manado under the Permesta group, after Bukittinggi had been captured by the government.[90] Within the group, Sumitro was considered an imporant When the federal "United Republic of Indonesia" was announced by the PRRI leaders in Sumatra in February 1960, Sumitro opposed the idea as he preferred an unitary state, and he did not want to work with the Darul Islam movement.[91][92] Additionally, due to Sumitro's involvement in the rebellion, many of his students who had pursued further education in foreign universities were excluded from the government.[93] As the movement was eventually defeated, Sumitro opted to remain abroad in exile,[94] and in 1961 founded Gerakan Pembaruan Indonesia (GPI), an underground anti-Sukarno movement. GPI and Sumitro openly opposed Sukarno, in contrast to other Indonesian exiles at the time such as Soedjatmoko who adopted a policy of partial collaboration.[95]

While abroad, Sumitro himself worked as a consultant, mostly in Singapore.[96] At times he went to Europe, on one occasion visiting Sjahrir during the latter's medical treatment in Switzerland.[97] He had also lived in Malaysia, and later in Bangkok.[98] While in Malaysia, he wrote a book on the economic history of the region in order to fund himself.[99] He corresponded with anti-communist military officers during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, and supported an attempt to revive the banned PSI although many of his former colleagues viewed him negatively due to his participation in the rebellion.[100] Sukarno had offered him a pardon, but as this would require him to recognize Sukarno's leadership, Sumitro refused.[13]

New Order

Minister of Trade

Following the fall of Sukarno and the ascent of Suharto as president, Suharto appointed Sumitro's former students such as Widjojo Nitisastro, Mohammad Sadli, Emil Salim and Subroto as advisers and ministers.[101][102] Suharto's personal staffer Ali Murtopo was tasked with bringing Sumitro back to Indonesia, and after meeting him in Bangkok in March 1967, Sumitro was convinced to return to Indonesia. Aside from his economic expertise, according to Sumitro he was also invited back to facilitate a normalization of relations between Indonesia and Malaysia in the aftermath of the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation. His arrival, in mid-1967, was kept secret for around three months, in order to hide Sumitro from Sukarno's remaining loyalists.[103]

Appointed as Minister of Trade and Industry in the First Development Cabinet in June 1968, Sumitro introduced restrictions on imports and created a "complementary foreign exchange" system to incentivize specific exports and discourage certain imports.[104] To maximize exports, Sumitro established agencies in the coffee and copra industries to manage quality and export policies,[105] while encouraging industrialization in the rubber industry by banning the exports of low-quality rubber and incentivizing investment in rubber processing factories.[106] Sumitro also encouraged a shift in imports from consumer goods to capital goods, while stating his intent to increase duties to generate government revenue.[107] However, he did not have full control over government economic policymaking, having to consult with other ministers and with Hamengkubuwono IX, the economic coordinating minister.[108] This cabinet was the first to include the Berkeley Mafia, a group of Western-educated economists with Sumitro being a key member and some others such as Finance Minister Ali Wardhana being former students of Sumitro.[104][109] Sumitro also was part of Suharto's economic advisory team in this period.[110]

Minister of Research

In 1973, Sumitro was reassigned as Minister of Research in the Second Development Cabinet.[111] In part, this reassignment to a less powerful position was due to disagreements in economic views with Suharto.[89] Several years into his tenure, Indonesian university students began to openly criticize government development policies, having initially been silenced by crackdowns following the 1974 Malari incident. In August 1977, Sumitro and several other ministers began touring Indonesian universities in an attempt to explain the policies to the students, but the meetings instead resulted in students confronting him on government corruption and military involvement in politics. By the middle of the month, accepting that the attempt had been a failure, Sumitro instead warned the students that any attempt to create a political movement will be dealt with "sternly."[112]

Sumitro also created a national research program involving a number of economics faculties and research institutes in the country in order to help formulate government economic policies by gaining an insight into the country's long-term growth prospects. Sumitro did this as he was concerned that Suharto's Five-Year Plans were not sufficiently taking into account long-term trends and visions. Despite its utilization in planning, the study was ceased when Sumitro was replaced by Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie in 1978.[111] Not long after his removal in office, he along with Chairman of the National Audit Board Umar Wirahadikusumah published an estimate which stated that around one-third of the national budget were lost due to either waste or corruption.[113]

Private career

Outside of his government career, Sumitro also engaged in private business, leveraging his political connections and foreign networks in Europe and the United States.[114] He founded Indoconsult Associates, one of the first business consulting firms in the country, with Mochtar Lubis, in July 1967.[115] Sumitro was also significantly involved in the rise of the Astra conglomerate, when in 1968 he helped the company gain a sole distributorship of Toyota vehicles in the country. The company's founders, the Tjia family, had developed relations with Sumitro since the 1950s.[116] He was president commissioner of Astra in 1992, when the group faced a takeover, and Sumitro resigned in December that year.[117] He was a founding member of the academic group East Asian Economic Association in 1984, and served as its first president.[118]

While no longer a government minister, Sumitro still held considerable influence in policymaking circles due to many of his former pupils holding government positions during the 1980s, and his continued teaching at Universitas Indonesia.[119] By the early 1980s, the Indonesian state-owned enterprises'role in the economy had been scaled down in favor of increased private sector participation, to the extent that Sumitro had advised.[120] Sumitro then began to develop concerns on the structure of the Indonesian economy under Suharto as time went on. While industrialization did progress rapidly, Sumitro was concerned with the presence of "special interests" which held ownership in many industries, and the excessive protectionist policies of the government.[121] Despite his previous Keynesian policies of extensive state involvement, he subsequently viewed the Indonesian economy as overregulated and in need of deregulation.[122] He considered Indonesia's industry to be fundamentally fragile, and only appeared to be productive at the surface level.[123] By the 1990s, he became more a critic of "rent-seeking activities", and ridiculed outright the Timor "national car" project in 1996. When the Asian financial crisis struck Indonesia late in the decade, Sumitro blamed institutional problems and corruption for the impact, and called for "immediate and firm action".[121] While his influence in government policymaking was diminished, he continued to play a role in Golkar party politics, supporting the unsuccessful attempt to nominate Emil Salim as Vice President in early 1998.[124]

Family and personal life

Two of Sumitro's brothers, Subianto and Subandio, were active in the Indonesian youth movement and were both killed during the Lengkong incident of 1946.[125] He married Dora Marie Sigar, whom he had met during his time in the Netherlands, on 7 January 1947. They were of different religion - Dora was a Manadonese Christian and Sumitro was a Muslim.[126] The couple has four children,[127] including military general-politician Prabowo Subianto (multiple time presidential candidate) and businessman Hashim Djojohadikusumo.[128] His family had followed Sumitro into exile following PRRI's defeat.[114] Sumitro's family has often been described as a political dynasty, their involvement in politics originating from Margono and extending four generations to post-Suharto legislators such as Rahayu Saraswati and Aryo Djojohadikusumo (both Hashim's children).[129] Prabowo was also married to Titiek Suharto, one of Suharto's daughters.[130] Following Prabowo's removal from the military due to his involvement in the 1997–98 activists kidnappings in Indonesia, Sumitro wrote in defence of his son, and accused either Wiranto (Prabowo's superior officer) or B. J. Habibie (vice president at the time) in his biography of pinning the blame on Prabowo.[131]

Sumitro was an avid tennis player and a heavy smoker.[132] He had written 130 books and articles mostly on economic matters between 1942 and 1994.[133]

Views

According to Sumitro, as a student, his views were strongly influenced by Joseph Schumpeter, Frank Knight, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and Irving Fisher.[134] He was also influenced by the Fabian Society of the London School of Economics.[135] While he disliked the enforcement of various quotas and restrictions on trade, he acknowledged that it was politically impossible for Indonesia during his time to engage in a complete free-market economic regime, and many of his policies were based by an intention to remove Dutch influence from the Indonesian economy;[136] his opposition to Sjafruddin Prawiranegara's policies were due to his view that such policies were simply a continuation of the Dutch approach.[137] He saw the previous colonial economy as creating two separate systems: one of subsistence economics and another of commercial, and subscribed to the theories of W. Arthur Lewis that low productivity generated from subsistence economics can be improved through the encouragement of industrialisation.[138] To accomplish this, Sumitro wrote in support of foreign investments, with caveats on domestic capital and labor participation, human development, and reinvestment of profits within Indonesia.[139]

Due to Sumitro's preference for a technocracy and industrialisation, he viewed the Western Bloc more favorably in the Cold War, and he was an ardent anti-communist. While politically under PSI, he did not subscribe to social democratic views held by the party's ideologues.[135] He also endorsed the development of cooperatives to develop the Indonesian rural economy.[140] In regards to government fiscal policy, Sumitro wrote in support of a balanced budget primarily as a means of disciplining government expenditures, but was opposed to cuts in development spending.[141] During the early Sukarno period, Sumitro also viewed income redistribution in developing countries such as Indonesia as more achievable through strong labor unions instead of through redistributive taxation.[120]

Death and funeral

Sumitro died just past midnight on 9 March 2001 at the Dharma Nugraha Hospital in Rawamangun, East Jakarta due to heart failure. He had been suffering from a heart disease for some time.[13][133] He was buried in Karet Bivak Cemetery.[142]

Legacy

In a 1986 interview, Sumitro commented on his multiple rises and falls in politics, saying that he "never won a political battle but [...] learnt how to survive defeats".[143] His critics describe him as a political opportunist, due to his distancing from former Socialist Party members during the Suharto period and his son Prabowo's marriage to Titiek.[13] Sumitro's role in Indonesia's early formation and his economic policies have prominently featured in the electoral campaigns of his son's political party, Gerindras.[144]

Sumitro has been described by various authors as a highly influential economist in both the Sukarno and Suharto periods, and often as the most influential altogether.[145][146][147][148] In his obituary, The Jakarta Post described him as "the father of modern Indonesian economics", with many of his writings being incorporated into standard textbooks on economics in Indonesia.[13]

Notes

- ^ Sumitro's brother, Subianto, had been one of Sjahrir's followers during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies.[32]

- ^ He had also considered the London School of Economics, but the plan was scrapped due to the British Council's refusal to grant scholarships.[40]

- ^ Another account suggested that Sumitro had won the party vote, but the vote was annuled due to Sumitro's absence at the party congress.[61]

References

Citations

- ^ Ministry of Finance 1991, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f Thee Kian Wie 2001, p. 173.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, p. 3.

- ^ a b Niwandhono 2021, p. 167.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Djojohadikusumo 1986, p. 29.

- ^ Poeze, Dijk & van der Meulen 2008, p. 275.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Webster 2011, p. 262.

- ^ Poeze, Dijk & van der Meulen 2008, p. 317.

- ^ Niwandhono 2021, p. 168.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e "Sumitro Dies at 84 of Heart Failure". The Jakarta Post. 10 March 2001. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ British Documents on Foreign Affairs: Reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print. From 1951 through 1956. Asia, 1951-1956. Part V. Series E. LexisNexis. 2008. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-88692-723-3.

- ^ Foray 2021, p. 128.

- ^ Fakih 2015, p. 214.

- ^ Kronik Revolusi Indonesia 2 (1946) (in Indonesian). Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. 27 December 2005. p. 286. ISBN 978-979-9023-30-8.

- ^ a b c Kahin 2003, p. 339.

- ^ Foray 2021, p. 138.

- ^ Gardner 2019, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 110.

- ^ Niwandhono 2021, p. 170.

- ^ Gardner 2019, p. 84.

- ^ "INDONESIANS URGE U.S. HALT DUTCH AID; Envoy Calls for Political and Economic Help to Republic in Talk With Lovett". The New York Times. 21 December 1948. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Gardner 2019, p. 98.

- ^ Kahin 2003, pp. 439–443.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 39.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Gardner 2019, p. 91.

- ^ a b Lindblad 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 122.

- ^ Mrázek 2018, p. 288.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 143.

- ^ Lindblad 2008, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, pp. 141–144.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 29.

- ^ a b Thee Kian Wie 2001, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 124.

- ^ Niwandhono 2021, p. 185.

- ^ Gardner 2019, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 138.

- ^ Webster 2011, p. 263.

- ^ Lindblad 2008, p. 108.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, pp. 51–56.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 229.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Lindblad 2008, p. 111.

- ^ Lindblad 2008, p. 129.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 331–339.

- ^ Lindblad 2008, p. 179.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 419–420.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 126.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 147.

- ^ Setiono 2008, p. 758.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 479.

- ^ a b Niwandhono 2021, p. 118.

- ^ Niwandhono 2021, p. 164.

- ^ Feith 2006, pp. 450–455.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 458.

- ^ Feith 2006, p. 467.

- ^ Mrázek 2018, p. 406.

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2015, p. 206.

- ^ Lindblad 2008, p. 171.

- ^ Lindblad 2008, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Fakih 2015, pp. 217–220.

- ^ Fakih 2015, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Fakih 2015, p. 224.

- ^ "Dugaan Korupsi Menteri Sumitro". Historia (in Indonesian). 17 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Kahin & Kahin 1997, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Mrázek 2018, p. 450.

- ^ Kahin 1999, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Gardner 2019, p. 142.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 198.

- ^ a b Kahin & Kahin 1997, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, p. 120.

- ^ a b Kahin 1999, pp. 206–207.

- ^ a b Mrázek 2018, pp. 445–446.

- ^ Kahin 1999, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, p. 137.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, p. 140.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, p. 145.

- ^ a b Hill 2011, p. 226.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, p. 197.

- ^ Kahin & Kahin 1997, p. 202.

- ^ Kahin 1999, p. 224.

- ^ Thuỷ 2019, p. 168.

- ^ Gardner 2019, p. 162.

- ^ Hill 2011, p. 115.

- ^ Garrett, Banning N.; Barkley, Katherine (1971). Two, Three ... Many Vietnams: A Radical Reader on the Wars in Southeast Asia and the Conflicts at Home. Canfield Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-06-383867-3.

- ^ Mrázek 2018, p. 490.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, p. 252.

- ^ Djojohadikusumo 1986, p. 32.

- ^ Niwandhono 2021, p. 194.

- ^ Gardner 2019, p. 250.

- ^ Ichimura 2016, p. 442.

- ^ Ali Moertopo dan Jejaknya Pada Peristiwa Bersejarah Indonesia (in Indonesian). Tempo Publishing. pp. 36–39. ISBN 978-623-262-992-9.

- ^ a b Rice 1969, pp. 183–187.

- ^ Rice 1969, pp. 188–192.

- ^ Rice 1969, p. 193.

- ^ Rice 1969, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Rice 1969, p. 185.

- ^ Hill 2011, p. 118.

- ^ Ministry of Finance 1991, p. 62.

- ^ a b Thee Kian Wie 2001, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Jenkins 2010, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Jenkins 2010, p. 230.

- ^ a b Purdey 2016, p. 373.

- ^ Hill 2011, p. 122.

- ^ Setiono 2008, p. 1032.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, pp. 308–316.

- ^ Ichimura 2016, p. 443.

- ^ Contending Perspectives 1997, p. 79.

- ^ a b Rice 1983, p. 79.

- ^ a b Thee Kian Wie 2001, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Contending Perspectives 1997, p. 78.

- ^ Ministry of Finance 1991, p. 56.

- ^ Eklöf 1999, p. 132.

- ^ Purdey 2016, p. 379.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, p. 411.

- ^ Ahsan, Ivan Aulia (30 May 2018). "Jatuh Bangun Dinasti Djojohadikusumo dalam Politik Indonesia". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Purdey 2016, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Ichimura 2016, p. 440.

- ^ Matanasi, Petrik (13 February 2019). "Sumitro Pernah Bela Prabowo, Seperti Mien Uno Bela Sandiaga". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Katoppo 2000, p. 408.

- ^ a b "Sumitro Djojohadikusumo Meninggal Dunia". liputan6.com (in Indonesian). 9 March 2001. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Djojohadikusumo 1986, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Niwandhono 2021, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Djojohadikusumo 1986, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Niwandhono 2021, p. 177.

- ^ Niwandhono 2021, pp. 173–176.

- ^ Rice 1983, p. 68.

- ^ Rice 1983, p. 64.

- ^ Djojohadikusumo 1986, p. 38.

- ^ "Sumitro Minta Dimakamkan Secara Sederhana". Tempo (in Indonesian). 29 October 2003. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Purdey 2016, p. 382.

- ^ Purdey 2016, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Gardner 2019, p. 162: "Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, Indonesia's premier economist".

- ^ Thee Kian Wie 2012, p. 43: "The four most influential economic policymakers in the period of 1950–57 were undoubtedly Sumitro, Sjafruddin, Hatta, and Djuanda.".

- ^ Rice 1969, p. 183: "Dr. Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, probably Indonesia's most prominent economist.".

- ^ Contending Perspectives 1997, p. 189: "Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, the undisputed high-priest of Indonesian economic development thinking".

Sources

- Rupiah di tengah rentang sejarah: 45 tahun uang Republik Indonesia, 1946–1991 (in Indonesian). Ministry of Finance of Indonesia. 1991.

- The Politics of Economic Development in Indonesia: Contending Perspectives. Routledge. 1997. ISBN 978-0-415-14502-2.

- Djojohadikusumo, Sumitro (1986). "Recollections of My Career". Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. 22 (3): 27–39. doi:10.1080/00074918612331334874. ISSN 0007-4918.

- Eklöf, Stefan (1999). Indonesian politics in crisis: the long fall of Suharto, 1996-1998. Copenhagen, Denmark: NIAS. ISBN 87-87062-68-2.

- Fakih, Farabi (2015). "The Ambiguous Position of Economists during the 'Old Order', 1950–65". In Schrikker, Alicia; Touwen, Jeroen (eds.). Promises and Predicaments: Trade and Entrepreneurship in Colonial and Independent Indonesia in the 19th and 20th Centuries. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-851-5.

- Feith, Herbert (2006). The Decline of Constitutional Democracy in Indonesia. Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-979-3780-45-0.

- Foray, Jennifer L. (2021). "The Republic at the Table, with Decolonisation on the Agenda: The United Nations Security Council and the Question of Indonesian Representation, 1946–1947". Itinerario. 45 (1): 124–151. doi:10.1017/S0165115321000048.

- Gardner, Paul F. (2019). Shared Hopes, Separate Fears: Fifty Years Of U.S.-Indonesian Relations. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-97697-1.

- Hill, David T. (2011). Jurnalisme dan Politik di Indonesia: Biografi Kritis Mochtar Lubis (1922-2004) sebagai Pemimpin Redaksi dan Pengarang (in Indonesian). Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. ISBN 978-979-461-788-5.

- Ichimura, Shinichi (2016). "Professor Dr Sumitro Djojohadikusumo: An Obituary*". Asian Economic Journal. 30 (4): 439–444. doi:10.1111/asej.12108. ISSN 1351-3958.

- Jenkins, David (2010). Suharto and His Generals: Indonesian Military Politics, 1975-1983. Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-602-8397-49-0.

- Kahin, Audrey (1999). Rebellion to Integration: West Sumatra and the Indonesian Polity, 1926-1998. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-395-3.

- Kahin, Audrey; Kahin, George McTurnan (1997). Subversion as Foreign Policy: The Secret Eisenhower and Dulles Debacle in Indonesia. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97618-1.

- Kahin, George McTurnan (2003). Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. SEAP Publications. ISBN 978-0-87727-734-7.

- Katoppo, Aristides (2000). Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, jejak perlawanan begawan pejuang (in Indonesian). Pustaka Sinar Harapan. ISBN 978-979-416-632-1.

- Lindblad, J. Th (2008). Bridges to New Business: The Economic Decolonization of Indonesia. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-25397-1.

- Mrázek, Rudolf (2018). Sjahrir: Politics and Exile in Indonesia. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-1881-6.

- Niwandhono, Pradipto (2021). The Making of Modern Indonesian Intellectuals: The Indonesian Socialist Party (PSI) and Democratic Socialist Ideas, 1930s to mid-1970s (PhD). University of Sydney.

- Poeze, Harry A.; Dijk, Cornelis; van der Meulen, Inge (2008). Di negeri penjajah: orang Indonesia di negeri Belanda, 1600-1950 (in Indonesian). Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9101-23-5.

- Purdey, Jemma (2016). "Narratives to power: The case of the Djojohadikusumo family dynasty over four generations". South East Asia Research. 24 (3): 369–385. doi:10.1177/0967828X16659728.

- Rice, Robert (1969). "Sumitro's Role in Foreign Trade Policy". Indonesia (8): 183–211. doi:10.2307/3350674. hdl:1813/53469. ISSN 0019-7289. JSTOR 3350674.

- Rice, Robert (1983). "The Origins of Basic Economic Ideas and Their Impact on 'New Order' Policies". Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. 19 (2): 60–82. doi:10.1080/00074918312331334389.

- Setiono, Benny G. (2008). Tionghoa Dalam Pusaran Politik (in Indonesian). TransMedia. ISBN 978-979-799-052-7.

- Thee Kian Wie (August 2001). "In Memoriam: Professor Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, 1917-2001". Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. 37 (2): 173–181. doi:10.1080/00074910152390865. S2CID 154067950.

- Thee Kian Wie (2012). Indonesia's Economy Since Independence. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4379-63-2.

- Thee Kian Wie (2015). "The Indonesian Economy during the 1950s and Early 1960s and America's Proposal for Economic Aid". Promises and Predicaments: Trade and Entrepreneurship in Colonial and Independent Indonesia in the 19th and 20th Centuries. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-851-5.

- Thuỷ, Phạm Văn (1 January 2019). Beyond Political Skin: Colonial to National Economies in Indonesia and Vietnam (1910s-1960s). Springer. ISBN 978-981-13-3711-6.

- Webster, David (2011). "Development advisors in a time of cold war and decolonization: the United Nations Technical Assistance Administration, 1950–59". Journal of Global History. 6 (2): 249–272. doi:10.1017/S1740022811000258.