Roy Orbison

Roy Orbison | |

|---|---|

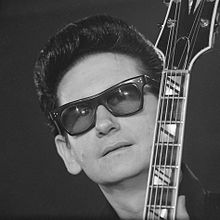

Orbison in 1965 | |

| Born | April 23, 1936 Vernon, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | December 6, 1988 (aged 52) |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5, including, Alex |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Roy Orbison discography |

| Years active | 1953–1988 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | royorbison |

Roy Kelton Orbison (April 23, 1936 – December 6, 1988) was an American singer, songwriter, and musician known for his distinctive and powerful voice, complex song structures, and dark, emotional ballads. Orbison's music is mostly in the rock genre and his most successful periods were in the early 1960s and the late 1980s. His music was described by critics as operatic, earning him the nicknames "The Caruso of Rock" and "The Big O". Many of Orbison's songs conveyed vulnerability at a time when most male rock-and-roll performers projected machismo. He performed with minimal motion and in black clothes, matching his dyed black hair and dark sunglasses.

Born in Texas, Orbison began singing in a rockabilly and country-and-western band as a teenager. He was signed by Sam Phillips of Sun Records in 1956, but enjoyed his greatest success with Monument Records. From 1960 to 1966, 22 of Orbison's singles reached the Billboard Top 40. He wrote or co-wrote almost all of his own Top 10 hits, including "Only the Lonely" (1960), "Running Scared" (1961), "Crying" (1961), "In Dreams" (1963), and "Oh, Pretty Woman" (1964).

After the mid-1960s Orbison suffered a number of personal tragedies, and his career faltered. He experienced a resurgence in popularity in the 1980s, following the success of several cover versions of his songs. In 1988, he co-founded the Traveling Wilburys supergroup with George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, and Jeff Lynne. Orbison died of a heart attack that December at age 52. One month later, his song "You Got It" (1989) was released as a solo single, becoming his first hit to reach both the US and UK Top 10 in nearly 25 years.

Orbison's honors include inductions into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1987, the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1989, and the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum in 2014. He received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and five other Grammy Awards. Rolling Stone placed him at number 37 on its list of the "Greatest Artists of All Time" and number 13 on its list of the "100 Greatest Singers of All Time". In 2002, Billboard magazine listed him at number 74 on its list of the Top 600 recording artists.

Early life

Orbison was born on April 23, 1936, in Vernon, Texas.[1] He was the second of three sons born to Orbie Lee Orbison (1913–1984) and Nadine Vesta Shults (1914–1992). Orbison’s direct paternal ancestor was traced to Thomas Orbison (born 1715) from Lurgan, Northern Ireland, who settled in the Province of Pennsylvania in the middle of the century.[2] According to The Authorized Roy Orbison, a biography written by Roy's son Alex, the family moved to Fort Worth in 1942 to find work in the aircraft factories.[3] He attended Denver Avenue Elementary School[3] there until a polio scare prompted the family to return to Vernon.

Orbison's father gave him a guitar on his sixth birthday, and Roy was taught how to play it by his father and older brother.[4] Roy recalled, "I was finished, you know, for anything else" by the time he was 7, and music became the focus of his life.[5] His major musical influence as a youth was country music. He was particularly moved by Lefty Frizzell's singing, with its slurred syllables,[6] leading Orbison to adopt the stage name "Lefty Wilbury" during his time with the Traveling Wilburys. He also enjoyed Hank Williams, Moon Mullican and Jimmie Rodgers. One of the first musicians that he heard in person was Ernest Tubb, playing on the back of a truck in Fort Worth. In West Texas, he was exposed to rhythm and blues, Tex-Mex, the orchestral arrangements of Mantovani, and Cajun music. The cajun favorite "Jole Blon" was one of the first songs that he sang in public. He began singing on a local radio show at age 8, and he became the show's host by the late 1940s.[7] At the age of 9, Orbison won a contest on radio station KVWC, which led to his own radio show where he sang the same songs every week.[4]

According to The Authorized Roy Orbison, the family moved again in 1946, to Wink, Texas.[8] Orbison described life in Wink as "football, oil fields, oil, grease, and sand"[9] and expressed relief that he was able to leave the desolate town.[a][11] All the Orbison children had poor eyesight; Roy used thick corrective lenses from an early age. He was self-conscious about his appearance and began dyeing his nearly-white hair black when he was still young.[12] He was quiet, self-effacing, and remarkably polite and obliging.[13] He was always keen to sing, however, and considered his voice memorable, but not great.[9]

In 1949, at the age of 13, Orbison and some friends formed the band Wink Westerners.[4] They played country standards and Glenn Miller songs at local honky-tonk bars and had a weekly morning radio show on KERB in Kermit, Texas.[14] Their first performance was at a school assembly in 1953.[4] They were offered $400 to play at a dance, and Orbison realized that he could make a living in music. Orbison was also part of a marching band and singing octet.[4]

He enrolled at North Texas State College in Denton, planning to study geology so that he could secure work in the oil fields if music did not pay.[15] He then heard that his schoolmate Pat Boone had signed a record deal, and it further strengthened his resolve to become a professional musician. He heard a song called "Ooby Dooby" while in college, composed by Dick Penner and Wade Moore, and he returned to Wink with "Ooby Dooby" in hand and continued performing with the Wink Westerners after his first year.[16] In 1955, he enrolled in Odessa Junior College, initially wanting to major in Geology but later switching to History and English.[4] Two members of the Wink Westerners band quit and two new members were added,[16] and the group won a talent contest and obtained their own television show on KMID-TV in Midland.[16] The Wink Westerners kept performing on local TV, played dances at the weekends, and attended college during the day.

While living in Odessa, Orbison saw a performance by Elvis Presley.[b] Johnny Cash toured the area in 1955 and 1956,[16] appearing on the same local TV show as the Wink Westerners,[16] and he suggested that Orbison approach Sam Phillips at Sun Records. Orbison did so and was told, "Johnny Cash doesn't run my record company!"[c] The success of their KMID television show got them another show on KOSA-TV, and they changed their name to the Teen Kings.[16] They recorded "Ooby Dooby" in 1956 for the Odessa-based Je–Wel label.[9][19] Record store owner Poppa Holifield played it over the telephone for Sam Phillips, and Phillips offered the Teen Kings a contract.[16]

Career

1956–1959: Sun Records and Acuff-Rose

The Teen Kings went to Sun Studio in Memphis, in order to re-record Ooby Dooby for publication by Sun Records. The song was released (as Sun Single 242) in May 1956[16] and broke into the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at number 59 and selling 200,000 copies.[9] The Teen Kings began an experimental tour of drive-in theatres in the southern U.S.A. states (playing on the projection house roofs between film showings) with Sonny James, Johnny Horton, Carl Perkins, and Cash[4]. Much influenced by Elvis Presley, Orbison performed frenetically, doing "everything we could to get applause because we had only one hit record".[20] Orbison also began writing songs in a rockabilly style, including Go! Go! Go! and Rockhouse.[21] In June of 1956, Ooby Dooby peaked at number 59 in the Billboard charts, however the follow-up singles didn't reach the charts[4].

The Teen Kings split in December 1956[4] over disputed writing credits and royalties[citation needed], but Orbison stayed in Memphis and asked his 16-year-old girlfriend, Claudette Frady, to join him there.[d] They stayed in Phillips' home, sleeping in separate rooms. In the studio, Orbison concentrated on the mechanics of recording. Phillips remembered being much more impressed with Orbison's mastery of the guitar than with his voice.[22] A ballad Orbison wrote, The Clown, met with a lukewarm response; after hearing it, Sun Records producer Jack Clement told Orbison that he would never make it as a ballad singer.[23]

Orbison was introduced to Elvis Presley's social circle, once going to pick up a date for Presley in his purple Cadillac. Orbison wrote Claudette—about Claudette Frady, whom he married in 1957—and The Everly Brothers recorded it as the B-side of All I Have to Do Is Dream. Claudette reached number 30 in the charts in March of 1959.[4] The first, and perhaps only, royalties Orbison earned from Sun Records enabled him to make a down payment on his own Cadillac[citation needed]. Increasingly frustrated at Sun, he gradually stopped recording. He toured music circuits around Texas and then quit performing for seven months in 1958.[24]

During the period of 1958-1959, Orbison made his living at Acuff-Rose Music[4], a songwriting firm concentrating mainly on country music. After spending an entire day writing a song, he would make several demonstration tapes at a time and send them to Wesley Rose, who would try to find musical acts to record them. Orbison then worked with, and was in awe of, Chet Atkins (who had played guitar with Presley) and attempted to sell his recordings of songs by other writers to the RCA Victor record label. One of these songs was Seems to Me, by Boudleaux Bryant. Bryant's impression of Orbison was of "a timid, shy kid who seemed to be rather befuddled by the whole music scene. I remember the way he sang then—softly, prettily but almost bashfully, as if someone might be disturbed by his efforts and reprimand him."[25]

Playing shows at night and living with his wife and young child in a tiny apartment, Orbison often took his guitar to his car to write songs. The songwriter Joe Melson, an acquaintance of Orbison's, tapped on his car window one day in Texas in 1958, and the two decided to write some songs together.[26] In three recording sessions in 1958 and 1959, Orbison recorded seven songs for RCA Victor at their Nashville studios; only two singles[which?] were judged worthy of release by the label.[27] Wesley Rose brought Orbison to the attention of the producer Fred Foster at Monument Records, the record label that Orbison would soon switch to[4].

1960–1964: Monument Records and stardom

Early singles

Orbison was one of the first recording artists to popularise the "Nashville sound", with a group of session musicians known as The Nashville A-Team[citation needed]. The Nashville sound was developed by producers Chet Atkins, Owen Bradley (who worked closely with Patsy Cline), Sam Phillips, bassist Bob Moore, and Fred Foster.[28][29] In his first session for Monument in Nashville, Orbison recorded a song that RCA Victor had refused, "Paper Boy", backed by "With the Bug", but neither charted.[30]

Orbison's own style, the sound created at RCA Victor Studio B in Nashville with pioneer engineer Bill Porter, the production by Foster, and the accompanying musicians gave Orbison's music a "polished, professional sound... finally allowing Orbison's stylistic inclinations free rein".[27] Orbison requested to use string instruments instead of fiddles, which was unusual for the time.[4]. He recorded three new songs, the most notable of which was "Uptown", written with Joe Melson and released in late 1959[4][31]. Impressed with the results, Melson later recalled, "We stood in the studio, listening to the playbacks, and thought it was the most beautiful sound in the world."[9][32] The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll states that the music Orbison made in Nashville "brought a new splendour to rock", and compared the melodramatic effects of the orchestral accompaniment to the musical productions of Phil Spector.[33]

"Uptown" reached only number 72 on the Billboard Top 100, and Orbison set his sights on negotiating a contract with an upscale nightclub somewhere[citation needed]. His initial success came just as the 1950s rock-and-roll era was winding down. Starting in 1960, the charts in the United States came to be dominated by teen idols, novelty acts, and Motown girl groups.[34]

1960–1962

Experimenting with a new sound, Orbison and Joe Melson wrote a song in early 1960 which, using elements from "Uptown", and another song they had written called "Come Back to Me (My Love)", employed strings and the Anita Kerr doo-wop backing singers.[35] It also featured a note hit by Orbison in falsetto that showcased a powerful voice which, according to biographer Clayson, "came not from his throat but deeper within".[36] The song was "Only the Lonely (Know the Way I Feel)". Orbison and Melson tried to pitch it to Elvis Presley and The Everly Brothers, but were turned down.[37] They instead recorded the song at RCA Victor's Nashville studio, with sound engineer Bill Porter trying a completely new strategy, building the mix from the top down rather than from the bottom up, beginning with close-miked backing vocals in the foreground, and ending with the rhythm section soft in the background.[31][38] This combination became Orbison's trademark sound.[35]

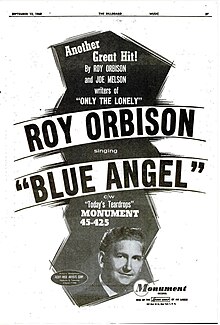

"Only the Lonely" shot to number two on the Billboard Hot 100 and hit number one in the UK and Australia.[4] According to Orbison, the subsequent songs he wrote with Melson during this period were constructed with his voice in mind, specifically to showcase its range and power. He told Rolling Stone in 1988, "I liked the sound of [my voice]. I liked making it sing, making the voice ring, and I just kept doing it. And I think that somewhere between the time of "Ooby Dooby" and "Only the Lonely", it kind of turned into a good voice."[39] Its success transformed Orbison into an overnight star and he appeared on Dick Clark's Saturday Night Beechnut Show out of New York City.[40] When Presley heard "Only the Lonely" for the first time, he bought a box of copies to pass to his friends.[41] Melson and Orbison followed it with the more complex "Blue Angel", which peaked at number nine in the US and number 11 in the UK. "I'm Hurtin'", with "I Can't Stop Loving You" as the B-side, rose to number 27 in the US, but failed to chart in the UK.[42]

Orbison was now able to move to Nashville permanently with his wife Claudette and son Roy DeWayne, born in 1958. Another son, Anthony King, would follow in 1962.[43] Back in the studio, seeking a change from the pop sound of "Only the Lonely", "Blue Angel", and "I'm Hurtin'",[44] Orbison worked on a new song, "Running Scared", based loosely on the rhythm of Maurice Ravel's Boléro; the song was about a man on the lookout for his girlfriend's previous boyfriend, who he feared would try to take her away[citation needed]. Orbison encountered difficulty when he found himself unable to hit the song's highest note without his voice breaking. He was backed by an orchestra in the studio, and Porter told him he would have to sing louder than his accompaniment because the orchestra was unable to be softer than his voice.[45] Fred Foster then put Orbison in the corner of the studio and surrounded him with coat racks forming an improvised isolation booth to emphasize his voice. Orbison was unhappy with the first two takes. In the third, however, he abandoned the idea of using falsetto and sang the final high 'A' naturally, so astonishing everyone present that the accompanying musicians stopped playing.[33] On that third take, "Running Scared" was completed. Fred Foster later recalled, "He did it, and everybody looked around in amazement. Nobody had heard anything like it before."[9] Just weeks later "Running Scared" reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart[4] and number 9 in the UK. The composition of Orbison's following hits reflected "Running Scared": a story about an emotionally vulnerable man facing loss or grief, with a crescendo culminating in a surprise climax that employed Orbison's dynamic voice.[42]

"Crying" followed in July 1961 and reached number two; it was coupled with an up-tempo R&B song, "Candy Man", written by Fred Neil and Beverley Ross, which reached the Billboard Top 30, staying on the charts for two months.[42] While Orbison was touring Australia in 1962, an Australian DJ referred to him affectionately as "The Big O", partly based on the big finishes to his dramatic ballads, and the moniker stuck with him thereafter. Orbison's second son was born the same year, and Orbison hit number four in the United States and number two in the UK with "Dream Baby (How Long Must I Dream)", an upbeat song by country songwriter Cindy Walker. Orbison enlisted The Webbs, from Dothan, Alabama, as his backing band. The band changed their names to The Candy Men (in reference to Roy's hit) and played with Orbison from 1962 to 1967.[46] They later went on to have their own career, releasing a few singles and two albums on their own. Also in 1962, he charted with "The Crowd", "Leah", and "Workin' for the Man", which he wrote about working one summer in the oil fields near Wink.[47][48] Orbison's relationship with Joe Melson, however, was deteriorating, over Melson's growing concerns that his own solo career would never get off the ground.[49]

From 1959-1963, Orbison was the top selling American artist and one of the world’s biggest names[4].

Public image

Orbison eventually developed an image that did not reflect his personality. He had no publicist in the early 1960s, and therefore had little presence in fan magazines, and his single sleeves did not feature his picture. Life called him an "anonymous celebrity".[51] After leaving his thick eyeglasses on an airplane in 1963, while on tour with the Beatles, Orbison was forced to wear his prescription Faosasunglasses on stage and found that he preferred them. The sunglasses led some people to assume he was blind.[52] His black clothes and song lyrics emphasized the image of mystery and introversion.[9][53][54] His dark and brooding persona, combined with his tremulous voice in lovelorn ballads marketed to teenagers, made Orbison a star in the early 1960s.

1963–1964

Orbison's string of top-40 hits continued with "In Dreams" (US number 7, UK number 6), "Falling" (US number 22, UK number 9), and "Mean Woman Blues" (US number 5, UK number 3) coupled with "Blue Bayou" (US number 29, UK number 3).[47][55] According to the discography in The Authorized Roy Orbison,[56] a rare alternative version of "Blue Bayou" was released in Italy. Orbison finished 1963 with a Christmas song written by Willie Nelson, "Pretty Paper" (US number 15 in 1963, UK number six in 1964).

As "In Dreams" was released in April 1963, Orbison was asked to replace Duane Eddy on a tour of the UK in top billing with the Beatles. The tour sold out in one afternoon[4]. When Orbison arrived in Britain, however, he realized he was no longer the main draw. He had never heard of the Beatles, and annoyed, asked rhetorically, "What's a Beatle, anyway?" to which John Lennon replied, after tapping his shoulder, "I am".[57] On the opening night, Orbison opted to go onstage first, although he was the more established act. The Beatles stood dumbfounded backstage as Orbison simply played through 14 encores.[58] Finally, when the audience began chanting "We want Roy!" again, Lennon and Paul McCartney physically held Orbison back.[59] Ringo Starr later said, "In Glasgow, we were all backstage listening to the tremendous applause he was getting. He was just standing there, not moving or anything."[58] Through the tour, however, the two acts quickly learned to get along, a process made easier by the fact that the Beatles admired his work.[60] Orbison felt a kinship with Lennon, but it was George Harrison with whom he would later form a strong friendship[citation needed].

In 1963, touring took a toll on Orbison's personal life. His wife Claudette had an affair with the contractor who built their home in Hendersonville, Tennessee. Friends and relatives attributed the breakdown of the marriage to her youth and her inability to withstand being alone and bored[citation needed]. When Orbison toured Britain again in the autumn of 1963, she joined him.[61]

Orbison was immensely popular wherever he went, finishing the tour in Ireland and Canada[citation needed]. In 1964, he toured Australia and New Zealand with the Beach Boys[4] and returned again to Britain and Ireland, where he was so besieged by teenaged girls that the Irish police had to halt his performances to pull the girls off him.[62] He travelled to Australia again in 1965, this time with the Rolling Stones[4]. Mick Jagger later remarked, referring to a snapshot he took of Orbison in New Zealand, "a fine figure of a man in the hot springs, he was."[63]

Oh, Pretty Woman

Orbison also began collaborating with Bill Dees, whom he had known in Texas. With Dees, he wrote "It's Over", a number-one hit in the UK and a song that would be one of his signature pieces for the rest of his career[citation needed]. When Claudette walked in the room where Dees and Orbison were writing to say she was heading for Nashville, Orbison asked if she had any money. Dees said, "A pretty woman never needs any money".[65] Just 40 minutes later, "Oh, Pretty Woman" was completed. A riff-laden masterpiece that employed a playful growl he got from a Bob Hope movie, the epithet mercy Orbison uttered when he was unable to hit a note, it rose to number one in the autumn of 1964 in the United States and stayed on the charts for 14 weeks. It rose to number one in the UK, as well, spending a total of 18 weeks on the charts. The single sold over seven million copies.[9] Orbison's success was greater in Britain; as Billboard magazine noted, "In a 68-week period that began on August 8, 1963, Roy Orbison was the only American artist to have a number-one single in Britain. He did it twice, with 'It's Over' on June 25, 1964, and 'Oh, Pretty Woman' on October 8, 1964. The latter song also went to number one in America, making Orbison impervious to the current chart dominance of British artists on both sides of the Atlantic."[66]

Oh, Pretty Woman went to number one in every country of the world and in Orbinson's most popular song[4].

1965–1969: Career decline and tragedies

Claudette and Orbison divorced in November 1964 over her infidelities, but reconciled 10 months later. His contract with Monument was expiring in June 1965. Wesley Rose, at this time acting as Orbison's agent, moved him from Monument Records to MGM Records (though in Europe he remained with Decca's London Records[67]) for $1 million and with the understanding that he would expand into television and films, as Elvis Presley had done. Orbison was a film enthusiast, and when not touring, writing, or recording, he dedicated time to seeing up to three films a day.[68]

Rose also became Orbison's producer. Fred Foster later suggested that Rose's takeover was responsible for the commercial failure of Orbison's work at MGM. Engineer Bill Porter agreed that Orbison's best work could only be achieved with RCA Victor's A-Team in Nashville.[30] Orbison's first collection at MGM, an album titled There Is Only One Roy Orbison, sold fewer than 200,000 copies.[9] With the onset of the British Invasion in 1964–65, the direction of popular music shifted dramatically, and most performers of Orbison's generation (Orbison was 28 in 1964) were driven from the charts.[69]

While on tour again in the UK in 1966,[70] Orbison broke his foot falling off a motorcycle in front of thousands of screaming fans at a race track; he performed his show that evening in a cast. Claudette travelled to Britain to accompany Roy for the remainder of the tour. It was now made public that the couple had happily remarried and were back together (they had remarried in December 1965).[71]

Orbison was fascinated with machines. He was known to follow a car that he liked and make the driver an offer on the spot.[72]

Orbison and Claudette shared a love for motorcycles; she had grown up around them, but Roy claimed Elvis Presley had introduced him to motorcycles.[73] On June 6, 1966, when Orbison and Claudette were riding home from Bristol, Tennessee, she struck the door of a pickup truck which had pulled out in front of her on South Water Avenue in Gallatin, Tennessee, and died instantly.[74]

A grieving Orbison threw himself into his work, collaborating with Bill Dees to write music for The Fastest Guitar Alive, a film that MGM had scheduled for him to star in as well. It was initially planned as a dramatic Western but was rewritten as a comedy.[75] Orbison's character was a spy who stole and had to protect and deliver a cache of gold to the Confederate Army during the American Civil War and was supplied with a guitar that turned into a rifle. The prop allowed him to deliver the line "I could kill you with this and play your funeral march at the same time", with, according to biographer Colin Escott, "zero conviction".[9] Orbison was pleased with the film, although it proved to be a critical and box-office failure. While MGM had included five films in his contract, no more were made.[76][77]

He recorded an album dedicated to the songs of Don Gibson and another of Hank Williams covers, but both sold poorly. During the counterculture era, with the charts dominated by artists like Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, the Rolling Stones, and the Doors, Orbison lost mainstream appeal, yet seemed confident that this would return, later saying: "[I] didn't hear a lot I could relate to, so I kind of stood there like a tree where the winds blow and the seasons change, and you're still there and you bloom again."[78]

During a tour of Britain and playing Birmingham on Saturday, September 14, 1968,[79] he received the news that his home in Hendersonville, Tennessee, had burned down, and his two eldest sons had died.[80] Fire officials stated that the cause of the fire may have been an aerosol can, which possibly contained lacquer.[81] The property was sold to Johnny Cash, who demolished the building and planted an orchard on it. On March 25, 1969, Orbison married German-born Barbara Jakobs, whom he had met several weeks before his sons' deaths.[82] Wesley (born 1965), his youngest son with Claudette, was raised by Orbison's parents. Orbison and Barbara had a son (Roy Kelton) in 1970 and another (Alexander) in 1975.[83]

1970s: Struggles

Orbison continued recording albums in the 1970s, but none of them sold well. By 1976, he had gone an entire decade without an album reaching the charts. He also failed to produce any popular singles, except for a few in Australia. His fortunes sank so low that he began to doubt his own talents, and several of his 1970s albums were not released internationally due to low US sales. He left MGM Records in 1973 and signed a one-album deal with Mercury Records.[84] Peter Lehman observed that Orbison's absence was a part of the mystery of his persona: "Since it was never clear where he had come from, no one seemed to pay much mind to where he had gone; he was just gone."[85] His influence was apparent, however, as several artists released popular covers of his songs. Orbison's version of "Love Hurts" was remade by Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris, again by hard rock band Nazareth, and by Jim Capaldi. Sonny James' version of "Only the Lonely" reached number one on the country music charts.[86] Bruce Springsteen ended his concerts with Orbison songs, and Glen Campbell had a minor hit with a remake of "Dream Baby".

A compilation of Orbison's greatest hits reached number one in the UK in January 1976, and Orbison began to open concerts that year for the Eagles, who had started as Linda Ronstadt's backup band. Ronstadt herself covered "Blue Bayou" in 1977, her version reaching number three on the Billboard charts and remaining in the charts for 24 weeks. Orbison credited this cover in particular for reviving his memory in the popular mind, if not his career.[87] He signed again with Monument in 1976 and recorded Regeneration with Fred Foster, but it proved no more successful than before.

In late 1977, Orbison was not feeling well and decided to spend the winter in Hawaii. He checked in to a hospital there where testing discovered that he had severely obstructed coronary arteries. He underwent a triple coronary bypass on January 18, 1978. He had suffered from duodenal ulcers since 1960 and had been a heavy smoker since adolescence.[88] Orbison said he felt rejuvenated after the procedure though his weight would continue to fluctuate for the rest of his life.

1980–1988: Career revival

In 1980, Don McLean recorded "Crying"[16] and it went to the top of the charts, first in the Netherlands then reaching number five in the US and staying on the charts for 15 weeks; it was number one in the UK for three weeks and also topped the Irish Charts.[89] In 1981 he performed "Pretty Woman" on an episode of The Dukes of Hazzard.[90] Orbison was all but forgotten in the US, yet he reached popularity in less likely places such as Bulgaria in 1982.[16] He was astonished to find that he was as popular there as he had been in 1964, and he was forced to stay in his hotel room because he was mobbed on the streets of Sofia.[91] In 1981, he and Emmylou Harris won a Grammy Award for their duet "That Lovin' You Feelin' Again" from the comedy film Roadie (in which Orbison also played a cameo role), and things were picking up.[92] It was Orbison's first Grammy, and he felt hopeful of making a full return to popular music,[93] In the meantime, Van Halen released a hard-rock cover of "Oh, Pretty Woman" on their 1982 album Diver Down, further exposing a younger generation to Orbison's music.[92]

It has been alleged that Orbison originally declined David Lynch's request to allow the use of "In Dreams" for the film Blue Velvet (1986),[94] although Lynch has stated to the contrary that he and his producers obtained permission to use the song without speaking to Orbison in the first place.[95] Lynch's first choice for a song had actually been "Crying";[96] the song served as one of several obsessions of a psychopathic character named Frank Booth (played by Dennis Hopper). It was lip-synched by Ben (Dean Stockwell), Booth's drug dealer boss, using an industrial work light as a pretend microphone, lighting his face.[97] In later scenes, Booth demands the song be played repeatedly; also wanting the song while beating the protagonist.[98] During filming, Lynch would also sit his cast down every few hours and ask them to listen to the song.[99] Orbison was initially shocked at its use: he saw the film in a theatre in Malibu and later said, "I was mortified because they were talking about the 'candy-coloured clown' in relation to a dope deal ... I thought, 'What in the world ...?' But later, when I was touring, we got the video out and I really got to appreciate what David gave to the song, and what the song gave to the movie—how it achieved this otherworldly quality that added a whole new dimension to 'In Dreams'."[9]

In 1987, Orbison released an album of re-recorded hits titled In Dreams: The Greatest Hits. "Life Fades Away", a song he co-wrote with his friend Glenn Danzig and recorded, was featured in the film Less than Zero (1987).[100] He and k.d. lang performed a duet of "Crying" for inclusion on the soundtrack to the film Hiding Out (1987); the pair received a Grammy Award for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals after Orbison's death.[101]

Also in 1987, Orbison was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame and was initiated into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by Bruce Springsteen, who concluded his speech with a reference to his own album Born to Run: "I wanted a record with words like Bob Dylan that sounded like Phil Spector—but, most of all, I wanted to sing like Roy Orbison. Now, everyone knows that no one sings like Roy Orbison."[102] In response, Orbison asked Springsteen for a copy of the speech, and said of his induction that he felt "validated" by the honor.[102]

A few months later, Orbison and Springsteen paired again to film a concert at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub in Los Angeles. They were joined by Jackson Browne, T Bone Burnett, Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, Bonnie Raitt, Jennifer Warnes, James Burton,[103] and k.d. lang. Lang later recounted how humbled Orbison had been by the display of support from so many talented and busy musicians: "Roy looked at all of us and said, 'If there is anything I can ever do for you, please call on me'. He was very serious. It was his way of thanking us. It was very emotional."[104] The concert was filmed in one take and aired on Cinemax under the title Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night; it was released on video by Virgin Records, selling 50,000 copies.[105]

In 1987, Orbison began collaborating seriously with Electric Light Orchestra bandleader Jeff Lynne on a new album. Lynne had just completed production work on George Harrison's Cloud Nine album, and all three ate lunch together one day when Orbison accepted an invitation to sing on Harrison's new single.[106] They subsequently contacted Bob Dylan, who, in turn, allowed them to use a recording studio in his home. Along the way, Harrison made a quick visit to Tom Petty's residence to obtain his guitar; Petty and his band had backed Dylan on his last tour.[107] By that evening, the group had written "Handle with Care", which led to the concept of recording an entire album. They called themselves the Traveling Wilburys, representing themselves as half-brothers with the same father. They gave themselves stage names; Orbison chose his from his musical hero, calling himself "Lefty Wilbury" after Lefty Frizzell.[108][109] Expanding on the concept of a traveling band of raucous musicians, Orbison offered a quote about the group's foundation in honor: "Some people say Daddy was a cad and a bounder. I remember him as a Baptist minister."[110]

Lynne later spoke of the recording sessions: "Everybody just sat there going, 'Wow, it's Roy Orbison!' ... Even though he's become your pal and you're hanging out and having a laugh and going to dinner, as soon as he gets behind that [mic] and he's doing his business, suddenly it's shudder time."[111] The band's debut album, Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 (1988), was released on October 25, 1988.[112] Orbison was given one solo track, "Not Alone Any More", on the album. His contributions were highly praised by the press.[101][113]

Orbison determinedly pursued his second chance at stardom, but he expressed amazement at his success: "It's very nice to be wanted again, but I still can't quite believe it."[114] He lost some weight to fit his new image and the constant demand of touring, as well as the newer demands of making videos. In the final three months of his life, he gave Rolling Stone magazine extensive access to his daily activities; he intended to write an autobiography and wanted Martin Sheen to play him in a biopic.[11]

Orbison completed a solo album, Mystery Girl, in November 1988.[115] Mystery Girl was co-produced by Jeff Lynne. Orbison considered Lynne to be the best producer with whom he had ever collaborated.[116] Elvis Costello, Bono, Orbison's son Wesley and others offered their songs to him.[47][55]

Around November 1988, Orbison confided in Johnny Cash that he was having chest pains. He went to Europe, was presented with an award there, and played a show in Antwerp, where footage for the video for "You Got It" was filmed. He gave several interviews a day in a hectic schedule. A few days later, a manager at a club in Boston was concerned that he looked ill, but Orbison played the show to a standing ovation.[115]

Death and aftermath

Death

Orbison performed at the Front Row Theater in Highland Heights, Ohio, on December 4, 1988. Exhausted, he returned to his home in Hendersonville to rest for several days before flying again to London to film two more videos for the Traveling Wilburys. On December 6, 1988, he spent the day flying model airplanes with his bus driver and friend Benny Birchfield and ate dinner at Birchfield's home in Hendersonville (Birchfield was married to country star Jean Shepard).[117] After he excused himself to go to the bathroom, Orbison collapsed and was rushed to the hospital, where he died of a heart attack at the age of 52.[118]

A memorial for Orbison was held in Nashville, and another was held in Los Angeles. He was buried at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in an unmarked grave.[119][120]

Aftermath

Mystery Girl was released by Virgin Records on January 31, 1989.[121] The biggest hit from Mystery Girl was "You Got It", written with Lynne and Tom Petty. "You Got It" rose to No. 9 in the US and No. 3 in the UK.[47][55] The song earned Orbison a posthumous Grammy Award nomination.[122] According to Rolling Stone, "Mystery Girl cloaks the epic sweep and grandeur of his classic sound in meticulous, modern production—the album encapsulates everything that made Orbison great, and for that reason it makes a fitting valedictory".[123]

Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 spent 53 weeks on the US charts, peaking at number three. It reached No. 1 in Australia and No. 16 in the UK. The album won a Grammy for Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group.[101] Rolling Stone included it in the top 100 albums of the decade.[113]

On April 8, 1989, Orbison became the first deceased musician since Elvis Presley to have two albums in the US Top Five at the same time, with Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 at number 4 and his own Mystery Girl at number 5.[124] In the United Kingdom, he achieved even greater posthumous success, with two solo albums in the Top 3 on February 11, 1989 (Mystery Girl was number 2 and the compilation The Legendary Roy Orbison was number 3).[125]

Although the video for the Traveling Wilburys' "Handle with Care" was filmed with Orbison, the video for "End of the Line" was filmed and released posthumously. During Orbison's vocal solo parts in "End of the Line", the video shows Orbison's guitar in a rocking chair next to Orbison's framed photo.[126]

On October 20, 1992, King of Hearts—another album of Orbison songs—was released.[127]

In 2014, a demo of Orbison's "The Way Is Love" was released as part of the 25th-anniversary deluxe edition of Mystery Girl. The song was originally recorded on a stereo cassette player around 1986. Orbison's sons contributed instrumentation on the track along with Orbison's vocals; it was produced by John Carter Cash.[128]

Style and legacy

"[Roy Orbison] was the true master of the romantic apocalypse you dreaded and knew was coming after the first night you whispered 'I Love You' to your first girlfriend. You were going down. Roy was the coolest uncool loser you'd ever seen. With his Coke-bottle black glasses, his three-octave range, he seemed to take joy sticking his knife deep into the hot belly of your teenage insecurities."

—Bruce Springsteen, 2012 SXSW Keynote Address[129]

Rock and roll in the 1950s was defined by a driving backbeat, heavy guitars, and lyrical themes that glorified youthful rebellion.[130] Few of Orbison's recordings have these characteristics. The structure and themes of his songs defied convention, and his much-praised voice and performance style were unlike any other in rock and roll.[according to whom?] Many of his contemporaries compared his music with that of classically trained musicians, although he never mentioned any classical music influences. Peter Lehman summarized it, writing, "He achieved what he did not by copying classical music but by creating a unique form of popular music that drew upon a wide variety of music popular during his youth."[131] Orbison was known as "the Caruso of Rock"[132][133] and "the Big O".[133]

Roys Boys LLC, a Nashville-based company founded by Orbison's sons to administer their father's catalog and safeguard his legacy, announced a November 16, 2018, release of Unchained Melodies: Roy Orbison with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra album as well as an autumn 2018 Roy Orbison Hologram tour called In Dreams: Roy Orbison in Concert.[134]

Songwriting

Structures

Music critic Dave Marsh wrote that Orbison's compositions "define a world unto themselves more completely than any other body of work in pop music".[135] Orbison's music, like the man himself, has been described as timeless, diverting from contemporary rock and roll and bordering on the eccentric, within a hair's breadth of being weird.[136] Peter Watrous, writing for the New York Times, declared in a concert review, "He has perfected an odd vision of popular music, one in which eccentricity and imagination beat back all the pressures toward conformity".[137]

In the 1960s, Orbison refused to splice edits of songs together and insisted on recording them in single takes with all the instruments and singers together.[138] The only convention Orbison followed in his most popular songs is the time limit for radio fare in pop songs. Otherwise, each seems to follow a separate structure. Using the standard 32-bar form for verses and choruses, normal pop songs followed the verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-verse-chorus structure. Where A represents the verse, B represents the chorus, and C the bridge, most pop songs can be represented by A-B-A-B-C-A-B, like "Ooby Dooby" and "Claudette". Orbison's "In Dreams" was a song in seven movements that can be represented as Intro-A-B-C-D-E-F; no sections are repeated. In "Running Scared", however, the entire song repeats to build suspense to a final climax, to be represented as A-A-A-A-B. "Crying" is more complex, changing parts toward the end to be represented as A-B-C-D-E-F-A-B'-C'-D'-E'-F'.[139] Although Orbison recorded and wrote standard structure songs before "Only the Lonely", he claimed never to have learned how to write them:[140]

I'm sure we had to study composition or something like that at school, and they'd say 'This is the way you do it,' and that's the way I would have done it, so being blessed again with not knowing what was wrong or what was right, I went on my own way. ... So the structure sometimes has the chorus at the end of the song, and sometimes there is no chorus, it just goes ... But that's always after the fact—as I'm writing, it all sounds natural and in sequence to me.

— Roy Orbison

Elton John's songwriting partner and main lyricist Bernie Taupin wrote that Orbison's songs always made "radical left turns", and k.d. lang declared that good songwriting comes from being constantly surprised, such as how the entirety of "Running Scared" eventually depends on the final note, one word.[141] Some of the musicians who worked with Orbison were confounded by what he asked them to do. The Nashville session guitarist Jerry Kennedy stated, "Roy went against the grain. The first time you'd hear something, it wouldn't sound right. But after a few playbacks, it would start to grow on you."[66]

Themes

Critic Dave Marsh categorizes Orbison's ballads into themes reflecting pain and loss, and dreaming. A third category is his uptempo rockabilly songs such as "Go! Go! Go!" and "Mean Woman Blues" that are more thematically simple, addressing his feelings and intentions in a masculine braggadocio. In concert, Orbison placed the uptempo songs between the ballads to keep from being too consistently dark or grim.[142]

In 1990, Colin Escott wrote an introduction to Orbison's biography published in a CD box set: "Orbison was the master of compression. Working the singles era, he could relate a short story, or establish a mood in under three minutes. If you think that's easy—try it. His greatest recordings were quite simply perfect; not a word or note surplus to intention."[9] After attending a show in 1988, Peter Watrous of The New York Times wrote that Orbison's songs are "dreamlike claustrophobically intimate set pieces".[137] Music critic Ken Emerson writes that the "apocalyptic romanticism" in Orbison's music was well-crafted for the films in which his songs appeared in the 1980s because the music was "so over-the-top that dreams become delusions, and self-pity paranoia", striking "a post-modern nerve".[143] Led Zeppelin singer Robert Plant favored American R&B music as a youth, but beyond the black musicians, he named Elvis and Orbison especially as foreshadowing the emotions he would experience: "The poignancy of the combination of lyric and voice was stunning. [Orbison] used drama to great effect and he wrote dramatically."[144]

The loneliness in Orbison's songs that he became most famous for, he both explained and downplayed: "I don't think I've been any more lonely than anyone else ... Although if you grow up in West Texas, there are a lot of ways to be lonely."[144] His music offered an alternative to the postured masculinity that was pervasive in music and culture. Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees stated, "He made emotion fashionable, that it was all right to talk about and sing about very emotional things. For men to sing about very emotional things ... Before that no one would do it."[144] Orbison acknowledged this in looking back on the era in which he became popular: "When ["Crying"] came out I don't think anyone had accepted the fact that a man should cry when he wants to cry."[144]

Voice quality

What separates Orbison from so many other multi-octave-spanning power singers is that he can hit the biggest notes imaginable and still sound unspeakably sad at the same time. All his vocal gymnastics were just a means to a powerful end, not a mission unto themselves. Roy Orbison didn't just sing beautifully—he sang brokenheartedly.

Orbison admitted that he did not think his voice was put to appropriate use until "Only the Lonely" in 1960, when it was able, in his words, to allow its "flowering".[146] Carl Perkins, however, toured with Orbison while they were both signed with Sun Records and recalled a specific concert when Orbison covered the Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald standard "Indian Love Call", and had the audience completely silenced, in awe.[147] When compared to The Everly Brothers, who often used the same session musicians, Orbison is credited with "a passionate intensity" that, according to The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll, made "his love, his life, and, indeed, the whole world [seem] to be coming to an end—not with a whimper, but an agonised, beautiful bang".[33]

Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel both commented on the otherworldly quality of Orbison's voice. Dwight Yoakam stated that Orbison's voice sounded like "the cry of an angel falling backward through an open window".[148] Barry Gibb of The Bee Gees went further to say that when he heard "Crying" for the first time, "That was it. To me that was the voice of God."[144] Elvis Presley stated Orbison's voice was the greatest and most distinctive he had ever heard.[149] Orbison's music and voice have been compared to opera by Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, and songwriter Will Jennings, among others.[150] Dylan marked Orbison as a specific influence, remarking that there was nothing like him on radio in the early 1960s:[151][which?]

With Roy, you didn't know if you were listening to mariachi or opera. He kept you on your toes. With him, it was all about fat and blood. He sounded like he was singing from an Olympian mountaintop. [After "Ooby Dooby"] he was now singing his compositions in three or four octaves that made you want to drive your car over a cliff. He sang like a professional criminal ... His voice could jar a corpse, always leave you muttering to yourself something like, "Man, I don't believe it".

— Bob Dylan

Likewise, Tim Goodwin, who conducted the orchestra that backed Orbison in Bulgaria, had been told that Orbison's voice would be a singular experience to hear. When Orbison started with "Crying" and hit the high notes, Goodwin stated: "The strings were playing and the band had built up and, sure enough, the hair on the back of my neck just all started standing up. It was an incredible physical sensation."[152] Bassist Jerry Scheff, who backed Orbison in his A Black and White Night concert, wrote about him, "Roy Orbison was like an opera singer. His voice melted out of his mouth into the stratosphere and back. He never seemed like he was trying to sing, he just did it."[153]

His voice ranged from baritone to tenor, and music scholars have suggested that he had a three- or four-octave range.[154]

Orbison's severe stage fright was particularly noticeable in the 1970s and early 1980s. During the first few songs in a concert, the vibrato in his voice was almost uncontrollable, but afterward, it became stronger and more dependable.[155] This also happened with age. Orbison noticed that he was unable to control the tremor in the late afternoon and evenings, and chose to record in the mornings when it was possible.[156]

Performance

Orbison often excused his motionless performances by saying that his songs did not allow instrumental sections so he could move or dance on stage, although songs like "Mean Woman Blues" did offer that.[157] He was aware of his unique performance style even in the early 1960s when he commented, "I'm not a super personality—on stage or off. I mean, you could put workers like Chubby Checker or Bobby Rydell in second-rate shows and they'd still shine through, but not me. I'd have to be prepared. People come to hear my music, my songs. That's what I have to give them."[158]

k.d. lang compared Orbison to a tree, with passive but solid beauty.[159] This image of Orbison as immovable was so associated with him it was parodied by John Belushi on Saturday Night Live, as Belushi dressed as Orbison falls over while singing "Oh, Pretty Woman", and continues to play as his bandmates set him upright again.[155] However, Lang quantified this style by saying, "It's so hard to explain what Roy's energy was like because he would fill a room with his energy and presence, but not say a word. Being that he was so grounded and so strong and so gentle and quiet. He was just there."[144]

Orbison attributed his own passion during his performances to the period when he grew up in Fort Worth while the US was mobilizing for World War II. His parents worked in a defense plant; his father brought out a guitar in the evenings, and their friends and relatives who had just joined the military gathered to drink and sing heartily. Orbison later reflected, "I guess that level of intensity made a big impression on me, because it's still there. That sense of 'do it for all it's worth and do it now and do it good.' Not to analyze it too much, but I think the verve and gusto that everybody felt and portrayed around me has stayed with me all this time."[160]

Discography

Studio albums

- Lonely and Blue (1961)

- Roy Orbison at the Rock House (1961)

- Crying (1962)

- In Dreams (1963)

- Oh, Pretty Woman (non-US) (1964)

- There Is Only One Roy Orbison (1965)

- Orbisongs (1965)

- The Orbison Way (1966)

- The Classic Roy Orbison (1966)

- Roy Orbison Sings Don Gibson/Sweet Dreams (Africa) (1967)

- Cry Softly Lonely One (1967)

- Roy Orbison's Many Moods (1969)

- Hank Williams the Roy Orbison Way (1970)

- The Big O (1970)

- Roy Orbison Sings (1972)

- Memphis (1972)

- Milestones (1973)

- I'm Still in Love with You (1975)

- Regeneration (1976)

- Laminar Flow (1979)

- Class of '55: Memphis Rock & Roll Homecoming (with Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Carl Perkins) (1986)

- In Dreams: The Greatest Hits (1987)

Posthumous albums

- Mystery Girl (1989)

- King of Hearts (1992)

- One of the Lonely Ones (2015)

Remix albums

- A Love So Beautiful (with The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) (2017)

- Unchained Melodies (with The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) (2018)

Honors

Rolling Stone placed him at number 37 on their list of the "Greatest Artists of All Time" and number 13 on their list of the "100 Greatest Singers of All Time'.[161] In 2002, Billboard magazine listed Orbison at number 74 in the Top 600 recording artists.[47]

- Grammy Awards[101]

- Best Country Performance Duo or Group (1980) ("That Lovin' You Feelin' Again", with Emmylou Harris)

- Best Spoken Word or Non-Musical Recording (1986) ("Interviews From The Class Of '55 Recording Sessions", with Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Sam Phillips, Rick Nelson and Chips Moman)

- Best Country Vocal Collaboration (1988) ("Crying", with k.d. lang)

- Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal (1989) (Traveling Wilburys Volume One, as a member of the Traveling Wilburys)

- Best Pop Vocal Performance, Male (1990) ("Oh, Pretty Woman")

- Lifetime Achievement Award (1998)

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1987)[39]

- Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame (1987)[140]

- Songwriters Hall of Fame (1989)[162]

- Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (2010)[163]

- America's Pop Music Hall of Fame (2014)

- Memphis Music Hall of Fame (2017)

See also

Video and televised feature performances:

- 1972: Live from Australia (Roy Orbison album)

- 1982: Live at Austin City Limits

- 1988: Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night

Notes

- ^ Ellis Amburn argues that Orbison was bullied and ostracized in Wink and that he gave conflicting reports to Texas newspapers, claiming that it was still home to him while simultaneously maligning the town to Rolling Stone.[10]

- ^ Orbison later said that he "couldn't overemphasize how shocking" Presley looked and seemed to him that night.[17]

- ^ Both Orbison and Cash mentioned this anecdote years later, but Phillips denied that he was so abrupt on the phone with Orbison or that he hung up on him. One of the Teen Kings later stated that the band did not meet Cash until they were on tour with him and other Sun Records artists.[18]

- ^ Alan Clayson's biography refers to her as Claudette Hestand.

References

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr. (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison. Wesley Orbison, Alex Orbison, Jeff Slate (first ed.). New York: Center Street. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ Kruth, John (2013). Rhapsody in Black: The Life and Music of Roy Orbison. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 9781480354920. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison, Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison (second ed.). New York: Center Street. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u https://royorbison.com/roy-orbison-official-biography/

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 7.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 21.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 8, 9.

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison, Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison. New York: Center Street. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Escott, Colin (1990). Biographical insert with The Legendary Roy Orbison CD box set. Sony. ASIN: B0000027E2.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 11–20.

- ^ a b Pond, Steve (January 26, 1989). "Roy Orbison's Triumphs and Tragedies". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 3.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 3, 9.

- ^ "History Maker". The Official Roy Orbison Site. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Slate, Orbison et al. (2017).

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 245.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 44.

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison. New York: Center Street. pp. 50, 57. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 45.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 56.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 62.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Zak, p. 32.

- ^ Wolfe and Akenson, p. 24.

- ^ Hoffmann and Ferstler, p. 779.

- ^ a b Zak, p. 33.

- ^ a b Lehman, p. 48.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c DeCurtis and Henke, p. 155.

- ^ Lehman, p. 19.

- ^ a b Zak, p. 35.

- ^ Clayson, p. 77.

- ^ Amburn p. 91.

- ^ Porter, Bill (January 1, 2006). "Recording Elvis and Roy With Legendary Studio Wiz Bill Porter-Part II". MusicAngle (Interview). Interviewed by Michael Fremer. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ a b "Roy Orbison". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 78.

- ^ Amburn, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Whitburn (2004), p. 470.

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison. New York: Center Street. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ Orbison, Roy; Orbison, Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison. New York: Center Street. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison, Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison. New York: Center Street. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ a b c d e Whitburn (2004), p. 524.

- ^ Amburn, p. 32.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 91.

- ^ Creswell, p. 600.

- ^ Lehman, p. 18.

- ^ Fontenot, Robert. "Top 10 Oldies Myths: Urban Legends and Other Misperceptions about Early Rock and Roll: 2. Roy Orbison Was Blind". About.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Amburn, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Brown, Kutner, and Warwick, p. 645.

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison, Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison (1st ed.). New York. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Amburn, p. 115.

- ^ a b Clayson, Alan, pp. 109–113.

- ^ Amburn, p. 117.

- ^ Lennon, John; McCartney, Paul; Harrison, George; Starr, Ringo (2002). The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle. p. 94.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Amburn, p. 125.

- ^ Amburn, p. 134.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 128, and Lehman, p. 169.

- ^ Amburn, p. 127.

- ^ a b Amburn, p. 128.

- ^ "Roy Orbison - Ride Away / Wondering - London - UK - HLU 9986". 45cat. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Lehman, p. 14

- ^ Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 131.

- ^ Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 129.

- ^ Amburn, p. 126.

- ^ Amburn, p. 54.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 139.

- ^ Lehman, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 152.

- ^ Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 144.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 161–63.

- ^ "Hendersonville, TN Home Fire Roy Orbison's House, Sep 1968 | GenDisasters ... Genealogy in Tragedy, Disasters, Fires, Floods". www.gendisasters.com. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ Amburn, p. 163.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 178.

- ^ Amburn, p. 170.

- ^ Lehman, p. 2.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Amburn, p. 178.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 3, 183–184.

- ^ Amburn, p. 182.

- ^ "The Great Hazzard Hijack". IMDb. March 27, 1981.

- ^ Amburn, p. 183.

- ^ a b Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 183.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 192.

- ^ Amburn, p. 191.

- ^ adamzanzie (September 5, 2019). "David Lynch on working with Roy Orbison". youtube.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 199.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (November 9, 2021). "Dean Stockwell in 'Blue Velvet': The Movie That Made Him Timeless". Variety.

- ^ Oisin H.C, Toni (December 1, 2021). "How 'Blue Velvet's Frank Booth Is an Allegory for Internalized Homophobia". Collider.

- ^ Amburn, p. 193.

- ^ "Glenn Danzig and Roy Orbison". RoyOrbison.com. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Grammy Award Results for Roy Orbison". Recording Academy GRAMMY Awards. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Clayson, Alan, pp. 202–203.

- ^ "Biography". The Official James Burton Website. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ Amburn, p. 207.

- ^ Amburn, p. 205.

- ^ Slate, Orbison et al. (2017), p. 211.

- ^ Amburn, p. 218.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Wild, David (October 18, 1988). "Traveling Wilburys Volume One". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Amburn, p. 221.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 208.

- ^ "The Traveling Wilburys, Vol. 1 - The Traveling Wilburys | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic" – via www.allmusic.com.

- ^ a b Amburn, p. 222.

- ^ Amburn, p. 223.

- ^ a b Amburn, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Amburn, p. 213.

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison Alex; Orbison, Wesley; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison. New York: Center Street. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 213.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 215.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 233–235.

- ^ Orbison, Roy Jr. (2017). The authorized Roy Orbison. Orbison, Wesley,, Orbison, Alex,, Slate, Jeff (Second ed.). New York: Center Street. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- ^ "Life after death: The best and worst posthumous albums". Yardbarker. November 16, 2020.

- ^ Azerrad, Michael (March 23, 1989). "Mystery Girl". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Top Pop Albums" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 101, no. 14. April 8, 1989. p. 80.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 75: 05 February 1989 - 11 February 1989". The Official UK Charts Company.

- ^ Lynne, Jeff; Harrison, George; Petty, Tom; Orbison, Roy; Dylan, Bob (May 20, 2016). The Traveling Wilburys - End Of The Line (Official Video). Traveling Wilburys (Music Video). Event occurs at 1:46. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "King of Hearts - Roy Orbison | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic" – via www.allmusic.com.

- ^ Sean Michaels (March 21, 2014). "Unreleased Roy Orbison track resurrected by singer's sons". The Guardian. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Tuttle, Mike (March 19, 2012). "Bruce Springsteen Schools 'Em At SXSW 2012". WebProNews. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ Lehman, p. 8.

- ^ Lehman, p. 58.

- ^ Amburn, p. 97.

- ^ a b Betts, Stephen L. (October 5, 2017). "Hear Roy Orbison Croon 'Oh, Pretty Woman' With the Royal Philharmonic". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Roy Orbison with Royal Philharmonic "Unchained Melodies" Releases 11/16, Includes Duet With Country Music Sensation Cam". Music News Net.

- ^ Lehman, p. 20.

- ^ Lehman, p. 9.

- ^ a b Watrous, Peter (July 31, 1988). "Roy Orbison Mines Some Old Gold". The New York Times. p. 48.

- ^ Lehman, p. 46.

- ^ Lehman, p. 53.

- ^ a b "Roy Orbison". Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. 2008. Archived from the original on January 2, 2009. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- ^ Lehman, p. 52.

- ^ Lehman, pp. 70–71.

- ^ DeCurtis and Henke, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e f Hall, Mark. (director) In Dreams: The Roy Orbison Story, Nashmount Productions Inc., 1999.

- ^ NPR staff (April 27, 2011). "Roy Orbison: Songs We Love". NPR. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Lehman, p. 50.

- ^ Lehman, p. 49.

- ^ Lehman, p. 22.

- ^ Amburn, pp. 175, 193.

- ^ Lehman, p. 21.

- ^ Dylan, p. 33.

- ^ Amburn, p. 184.

- ^ Scheff, Jerry (2012). Way Down: Playing Bass with Elvis, Dylan, the Doors & More. Backbeat Books. p. 33.

- ^ O'Grady, Terence J. (February 2000). "Orbison, Roy". American National Biography. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Lehman, p. 24.

- ^ Townsend, Paul (January 2, 2014), Roy Orbison, March 1967, Colston Hall, Bristol, retrieved October 24, 2019

- ^ Lehman, p. 62.

- ^ Clayson, Alan, p. 78.

- ^ Lang, k. d. (April 15, 2004). "The Immortals – The Greatest Artists of All Time: 37) Roy Orbison". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ^ Amburn, p. 7.

- ^ "100 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. November 27, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2011 – via Rolling Stone website.

- ^ "Roy Orbison". Songwriters Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- ^ Roy Orbison given Hollywood Walk of Fame star BBC News (January 30, 2010). Retrieved on January 31, 2010.

Sources

- Amburn, Ellis (1990). Dark Star: The Roy Orbison Story, Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8184-0518-X.

- Brown, Tony; Kutner, Jon; Warwick, Neil (2000). Complete Book of the British Charts: Singles & Albums, Omnibus. ISBN 0-7119-7670-8.

- Clayson, Alan (1989). Only the Lonely: Roy Orbison's Life and Legacy, St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-03961-1.

- Clayton, Lawrence; Sprecht, Joe, eds. (2003). The Roots of Texas Music, Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-997-0.

- Creswell, Toby (2006). 1001 Songs: The Greatest Songs of All Time and the Artists, Stories, and Secrets Behind Them, Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-915-9.

- DeCurtis, Anthony; Henke, James (eds.) (1992). The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Random House. ISBN 0-679-73728-6.

- Hoffman, Frank W., Ferstler, Howard (2005). Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound, Volume 1, CRC Press. ISBN 0-415-93835-X.

- Lehman, Peter (2003). Roy Orbison: The Invention of An Alternative Rock Masculinity, Temple University Press. ISBN 1-59213-037-2.

- Orbison, Roy Jr.; Orbison, Wesley; Orbison, Alex; Slate, Jeff (2017). The Authorized Roy Orbison (2nd ed.). New York: Center Street. ISBN 978-1-4789-7654-7. OCLC 1017566749.

- Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7499-4.

- Wolfe, Charles K., Akenson, James (eds.) (2000). Country Music Annual, issue 1. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0989-2.

- Zak, Albin (2010). "'Only The Lonely' — Roy Orbison's Sweet West Texas Style", pp. 18–41 in John Covach and Mark Spicer. Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music, University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-03400-6.

External links

- Hugo Keesing Collection on Roy Orbison — Special Collections in Performing Arts, University of Maryland

- Official website

- Roy Orbison at AllMusic

- Roy Orbison at IMDb

- Roy Orbison: The Big O Archived February 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine life story by Marie Claire Australia magazine

- 1936 births

- 1988 deaths

- 20th-century American guitarists

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- American country guitarists

- American country rock singers

- American country singer-songwriters

- American male guitarists

- American male singer-songwriters

- American rockabilly guitarists

- American rockabilly musicians

- American rock guitarists

- American rock songwriters

- American rock singers

- American tenors

- Asylum Records artists

- Ballad musicians

- Burials at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Guitarists from Texas

- Mercury Records artists

- MGM Records artists

- Monument Records artists

- Music of Denton, Texas

- Musicians from Texas

- Odessa College alumni

- People from Vernon, Texas

- People from Wilbarger County, Texas

- People from Winkler County, Texas

- RCA Victor artists

- Rock and roll musicians

- Roy Orbison

- Singers with a four-octave vocal range

- Singer-songwriters from Texas

- Sun Records artists

- Traveling Wilburys members

- University of North Texas alumni

- Virgin Records artists

- Winkler County, Texas