Mitosis

It has been suggested that Binary fission be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since September 2007. |

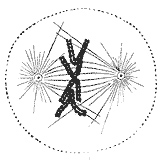

Mitosis is the process in which a cell duplicates its chromosomes to generate two identical nuclei. It is generally followed by cytokinesis which divides the cytoplasm and cell membrane. This results in two identical cells with an equal distribution of organelles and other cellular components. Mitosis and cytokinesis jointly define the mitotic (M) phase of the cell cycle, the division of the mother cell into two sister cells, each with the genetic equivalent of the parent cell. Mitosis occurs most often in eukaryotic cells.

In multicellular organisms, the somatic cells undergo mitosis, while germ cells — cells destined to become sperm in males or ova in females — divide by a related process called meiosis. Prokaryotic cells, which lack a nucleus, divide by a process called binary fission.

Process

The process of mitosis is complex and highly regulated. The sequence of events is organized into phases corresponding to the completion of certain phase prerequisites.

Various classes of cells can skip steps depending on the presence of protease inhibitors or if they are in a hurry. These stages are preprophase, prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, telophase and cytokinesis. During the process of mitosis the pairs of chromosomes condense and attach to fibers that pull the sister chromatids to opposite sides of the cell. The cell then divides in cytokinesis, to produce two identical daughter cells.

Cytokinesis usually occurs in conjunction with mitosis, "mitosis" is often used interchangeably with the phrase "mitotic phase". However, there are many cells whose mitosis and cytokinesis occur separately, forming single cells with multiple nuclei. This occurs most notably among the fungi and slime moulds, but is found in various different groups. Even in animals, cytokinesis and mitosis may occur independently, for instance during certain stages of fruit fly embryonic development.[1] Errors in mitosis can either kill a cell through apoptosis or cause mutations that may lead to cancer or cell death.

Phases

The process of Mitosis can be divided into seven stages: Preprophase, Prophase, Prometaphase, Metaphase, Anaphase, Telophase and Cytokinesis. Students often remember the main stages of the cell cycle (Interphase, Prophase, Metaphase, Anaphase and Telophase) by use of the acronym IPMAT.

Interphase

The mitotic phase is a relatively short period of the cell cycle. It alternates with the much longer interphase, where the cell bum prepares itself for cell division. Interphase is divided into three phases, G1 (first gap), S (synthesis), and G2 (second gap). During all three phases, the cell grows by producing proteins and cytoplasmic organelles. However, chromosomes are replicated only during the S phase. Thus, a cell grows (G1), grows as it duplicates its chromosomes (S), grows more and prepares for mitosis (G2), and divides (M).[2]

Preprophase

In plant cells only, prophase is preceded by a pre-prophase stage and followed by a post-prophase stage. In plant cells that are highly vacuolated and somewhat amorphoric, the nucleus has to migrate into the center of the cell before mitosis can begin. This is achieved through the formation of a phragmosome, a transverse sheet of cytoplasm that bisects the cell along the future plane of cell division. In addition to phragmosome formation, preprophase is characterized by the formation of a ring of microtubules and actin filaments (called preprophase band) underneath the plasmamembrane around the equatorial plane of the future mitotic spindle and predicting the position of cell plate fusion during telophase. The cells of higher plants (such as the flowering plants) lack centrioles. Instead, spindle microtubules aggregate on the surface of the nuclear envelope during prophase. The preprophase band disappears during nuclear envelope disassembly and spindle formation in prometaphase.[3]

Prophase

Normally, the genetic material in the nucleus is in a loosely bundled coil called chromatin. At the onset of prophase, chromatin condenses together into a highly ordered structure called a chromosome. Since the genetic material has already been duplicated earlier in S phase, the replicated chromosomes have two sister chromatids, bound together at the centromere by the cohesion complex. Chromosomes are visible at high magnification through a light microscope.

Close to the nucleus are two centrosomes. Each centrosome, which was replicated earlier independent of mitosis, acts as a coordinating center for the cell's microtubules. The two centrosomes nucleate microtubules (or microfibrils) (which may be thought of as cellular ropes) by polymerizing soluble tubulin present in the cytoplasm. Molecular motor proteins create repulsive forces that will push the centrosomes to opposite side of the nucleus. The centrosomes are only present in animals. In plants the microtubules form independently.

Some centrosomials contain a pair of centrioles that may help organize microtubule assembly, but they are not essential to formation of the mitotic spindle.[4]

hey jessie

Prometaphase

The nuclear envelope disassembles and microtubules invade the nuclear space. This is called open mitosis, and it occurs in most multicellular organisms. Fungi and some protists, such as algae or trichomonads, undergo a variation called closed mitosis where the spindle forms inside the nucleus or its microtubules are able to penetrate an intact nuclear envelope.[5][6]

Each chromosome forms two kinetochores at the centromere, one attached at each chromatid. A kinetochore is a complex protein structure that is analogous to a ring for the microtubule hook; it is the point where microtubules attach themselves to the chromosome.[7] Although the kinetochore structure and function are not fully understood, it is known that it contains some form of molecular motor.[8] When a microtubule connects with the kinetochore, the motor activates, using energy from ATP to "crawl" up the tube toward the originating centrosome. This motor activity, coupled with polymerisation and depolymerisation of microtubules, provides the pulling force necessary to later separate the chromosome's two chromatids.[8]

When the spindle grows to sufficient length, usually at least 7 nanometers, kinetochore microtubules begin searching for kinetochores to attach to. A number of nonkinetochore microtubules find and interact with corresponding nonkinetochore microtubules from the opposite centrosome to form the mitotic spindle.[9] Prometaphase is sometimes considered part of prophase.

yo!!!!

Metaphase

As microtubules find and attach to kinetochores in prometaphase, the centromeres of the chromosomes convene along the metaphase plate or equatorial plane, an imaginary line that is equidistant from the two centrosome poles.[9] This even alignment is due to the counterbalance of the pulling powers generated by the opposing kinetochores, analogous to a tug-of-war between equally strong people. In certain types of cells, chromosomes do not line up at the metaphase plate and instead move back and forth between the poles randomly, only roughly lining up along the midline. Metaphase comes from the Greek word for "metanosis" μετα meaning "after."

Because proper chromosome separation requires that every kinetochore be attached to a bundle of microtubules (spindle fibers) , it is thought that unattached kinetochores generate a signal to prevent premature progression to anaphase[1] without all chromosomes being aligned. The signal creates the mitotic spindle checkpoint.[10]

Anaphase

When every kinetochore is attached to a cluster of microtubules and the chromosomes have lined up along the metaphase plate, the cell proceeds to anaphase (from the Greek ανα meaning “up,” “against,” “back,” or “re-”).

Two events then occur; First, the proteins that bind sister chromatids together are cleaved, allowing them to separate. These sister chromatids are hereafter independent sister chromosomes. They are pulled apart by shortening kinetochore microtubules and toward the respective centrosomes to which they are attached. This is followed by the elongation of the nonkinetochore microtubules, which pushes the centrosomes (and the set of chromosomes to which they are attached) apart to opposite ends of the cell.

These three stages are sometimes called early, mid and late anaphase. Early anaphase is usually defined as the separation of the sister chromatids. Mid anaphase occurs with the reunification of certain metastic chromatids. Late anaphase is the elongation of the microtubules and the microtubules being pulled further apart. At the end of anaphase, the cell has succeeded in separating identical copies of the genetic material into two distinct populations.

Telophase

Telophase (from the Greek τελος meaning "end") is a reversal of prophase and prometaphase events. It "cleans up" the after effects of mitosis. At telophase, the nonkinetochore microtubules continue to lengthen, elongating the cell even more. Corresponding sister chromosomes attach at opposite ends of the cell. A new nuclear envelope, using fragments of the parent cell's nuclear membrane, forms around each set of separated sister chromosomes. Both sets of chromosomes, now surrounded by new nuclei, unfold back into chromatin. Mitosis is complete, but cell division is not yet complete.

Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis is often mistakenly thought to be the final part of telophase, however cytokinesis is a separate process that begins after telophase. Cytokinesis is technically not even a phase of mitosis, but rather a separate process, necessary for completing cell division. In animal cells, a cleavage furrow (pinch) containing a contractile ring develops where the metaphase plate used to be, pinching off the separated nuclei.[11] In both animal and plant cells, cell division is also driven by vesicles derived from the Golgi apparatus, which move along microtubules to the middle of the cell. [12] In plants this structure coalesces into a cell plate at the center of the phragmoplast and develops into a cell wall, separating the two nuclei. The phragmoplast is a microtubule structure typical for higher plants, whereas some green algae use a phycoplast microtubule array during cytokinesis.[13] Each daughter cell has a complete copy of the genome of its parent cell. The end of cytokinesis marks the end of the M-phase.

Consequences of errors

Although errors in mitosis are rare, the process may go wrong, especially during early cellular divisions in the zygote. Mitotic errors can be especially dangerous to the organism because future offspring from this parent cell will carry the same disorder.

In non-disjunction, a chromosome may fail to separate during anaphase. One daughter cell will receive both sister chromosomes and the other will receive none. This results in the former cell having three chromosomes coding for the same thing (two sisters and a homologue), a condition known as trisomy, and the latter cell having only one chromosome (the homologous chromosome), a condition known as monosomy. These cells are considered aneuploidic cells and these abnormal cells can cause cancer.[14]

Mitosis is a traumatic process. The cell goes through dramatic changes in ultrastructure, its organelles disintegrate and reform in a matter of hours, and chromosomes are jostled constantly by probing microtubules. Occasionally, chromosomes may become damaged. An arm of the chromosome may be broken and the fragment lost, causing deletion. The fragment may incorrectly reattach to another, non-homologous chromosome, causing translocation. It may reattach to the original chromosome, but in reverse orientation, causing inversion. Or, it may be treated erroneously as a separate chromosome, causing chromosomal duplication. The effect of these genetic abnormalities depend on the specific nature of the error. It may range from no noticeable effect, cancer induction, or organism death.

Endomitosis

Endomitosis is a variant of mitosis without nuclear or cellular division, resulting in cells with many copies of the same chromosome occupying a single nucleus. This process may also be referred to as endoreduplication and the cells as endoploid.[1]

Timeline in pictures

Real mitotic cells can be visualized through the microscope by staining them with fluorescent antibodies and dyes. These light micrographs are included below.

-

Early prophase: Nonkinetochore microtubules, shown as green strands, have established a matrix around the degrading nucleus, in blue. The green nodules are the centrosomes.

-

Early prometaphase: The nuclear membrane has just degraded, allowing the microtubules to quickly interact with the kinetochores on the chromosomes, which have just condensed.

-

Late metaphase: The centrosomes have moved to the poles of the cell and have established the mitotic spindle. The chromosomes, in light blue, have all assembled at the metaphase plate, except for one.

-

Anaphase: Lengthening nonkinetochore microtubules push the two sets of chromosomes further apart.

References

- ^ a b Lilly M, Duronio R (2005). "New insights into cell cycle control from the Drosophila endocycle". Oncogene. 24 (17): 2765–75. PMID 15838513.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Blowwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Raven, Peter H. (2005). Biology of Plants, 7th Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company Publishers. pp. 58–67. ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lloyd C, Chan J. (2006). "Not so divided: the common basis of plant and animal cell division". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 7 (2): 147–52. PMID 16493420.

- ^ Heywood P. (1978). "Ultrastructure of mitosis in the chloromonadophycean alga Vacuolaria virescens". J Cell Sci. 31: 37–51. PMID 670329.

- ^ Ribeiro K, Pereira-Neves A, Benchimol M (2002). "The mitotic spindle and associated membranes in the closed mitosis of trichomonads". Biol Cell. 94 (3): 157–72. PMID 12206655.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chan G, Liu S, Yen T (2005). "Kinetochore structure and function". Trends Cell Biol. 15 (11): 589–98. PMID 16214339.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maiato H, DeLuca J, Salmon E, Earnshaw W (2004). "The dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface". J Cell Sci. 117 (Pt 23): 5461–77. PMID 15509863.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Winey M, Mamay C, O'Toole E, Mastronarde D, Giddings T, McDonald K, McIntosh J (1995). "Three-dimensional ultrastructural analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitotic spindle". J Cell Biol. 129 (6): 1601–15. PMID 7790357.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chan G, Yen T. "The mitotic checkpoint: a signaling pathway that allows a single unattached kinetochore to inhibit mitotic exit". Prog Cell Cycle Res. 5: 431–9. PMID 14593737.

- ^ Glotzer M (2005). "The molecular requirements for cytokinesis". Science. 307 (5716): 1735–9. PMID 15774750.

- ^ Albertson R, Riggs B, Sullivan W (2005). "Membrane traffic: a driving force in cytokinesis". Trends Cell Biol. 15 (2): 92–101. PMID 15695096.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Raven, Peter H. (2005). Biology of Plants, 7th Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company Publishers. pp. 64–67, 328–329. ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Draviam V, Xie S, Sorger P (2004). "Chromosome segregation and genomic stability". Curr Opin Genet Dev. 14 (2): 120–5. PMID 15196457.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Morgan DO (2007) "The Cell Cycle: Principles of Control" London: New Science Press.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, and Walter P (2002). "Mitosis". Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. Retrieved January 22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Campbell, N. and Reece, J. (December 2001). "The Cell Cycle". Biology (6th ed. ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings/Addison-Wesley. pp. pp. 217-224. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cooper, G. (2000). "The Events of M Phase". The Cell: A Molecular Approach. Sinaeur Associates, Inc. Retrieved January 22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Freeman, f (2002). "Cell Division". Biological Science. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. pp. 155-174. ISBN 0-13-081923-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky L, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J (2000). "Overview of the Cell Cycle and Its Control". Molecular Cell Biology. W.H. Freeman. Retrieved January 22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Microscopic Hematology: Mitosis in Human Bone Marrow:Presented by the University of Virginia.

- Science aid: Mitosis and meiosis: A simple account of the mitotic and meiotic processes.

- Mitosis Animation.

- Video of a live amphibian lung cell undergoing mitosis.