Oganesson

| Oganesson | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | metallic (predicted) | |||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [294] | |||||||||||||||||

| Oganesson in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 118 | |||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 18 (noble gases) | |||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f14 6d10 7s2 7p6 (predicted)[3][4] | |||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 18, 8 (predicted) | |||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid (predicted)[5] | |||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 325 ± 15 K (52 ± 15 °C, 125 ± 27 °F) (predicted)[5] | |||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 450 ± 10 K (177 ± 10 °C, 350 ± 18 °F) (predicted)[5] | |||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 7.2 g/cm3 (solid, 319 K, calculated)[5] | |||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 6.6 g/cm3 (liquid, 327 K, calculated)[5] | |||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | (−1),[4] (0), (+1),[6] (+2),[7] (+4),[7] (+6)[4] (predicted) | |||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | ||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 152 pm (predicted)[9] | |||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 157 pm (predicted)[10] | |||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | synthetic | |||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) (extrapolated)[11] | |||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 54144-19-3 | |||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Yuri Oganessian | |||||||||||||||||

| Prediction | Hans Peter Jørgen Julius Thomsen (1895) | |||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Joint Institute for Nuclear Research and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (2002) | |||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of oganesson | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

Ununoctium (Template:PronEng[15][16] and also known as eka-radon or element 118) is the temporary IUPAC name[17] for the transactinide element having the atomic number 118 and temporary element symbol Uuo. On the periodic table of the elements, it is a p-block element and the last one of the 7th period. Ununoctium is currently the only synthetic member of group 18 (the noble gases) and has the highest atomic number and highest atomic mass assigned to a discovered element.

The radioactive ununoctium atom is very unstable, and since 2002, only three atoms of the isotope 294Uuo have been detected.[18] While this allowed for very little experimental characterization of its properties and its compounds, theoretical calculations have allowed for many predictions, including some very unexpected ones. For example, although ununoctium is a member of the noble gas group, it could have a higher chemical reactivity than some elements outside this group.[19] Furthermore, it is predicted that it might not even be a gas under normal conditions.[19][20]

History

Unsuccessful attempts

In late 1998, the Polish physicist Robert Smolanczuk published some calculations on the fusion of atomic nuclei towards the synthesis of superheavy atoms, including the element 118.[21] His calculations suggested that it might be possible to make element 118 by fusing lead with krypton under carefully controlled conditions.[21]

In 1999, researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory made use of these predictions and announced the discovery of elements 116 and 118, in a paper published in Physical Review Letters,[22] and very soon after the results were reported in Science.[23] The researchers claimed to have performed the reaction:

The following year, they published a retraction after other researchers were unable to duplicate the results.[24] In June 2002, the director of the lab announced that the original claim of the discovery of these two elements had been based on data fabricated by principal author Victor Ninov.[25]

Discovery

On October 16, 2006, researchers from Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory of California, USA, working at the JINR in Dubna, Russia, announced in Physical Review C that they had indirectly detected a total of three nuclei of ununoctium-294 (one in 2002[26] and two more in 2005) produced via collisions of californium-249 atoms and calcium-48 ions:[27][28][29][30][31]

Because of the very small fusion reaction probability (the fusion cross section is 0.5 pb = 5×10−41 m2) the experiment took 4 months and involved a beam dose of 4×1019 calcium ions that had to be shot at the californium target to produce the first recorded event believed to be the synthesis of ununoctium.[33] Nevertheless, researchers are highly confident that the results are not a false positive, since the chance that the detections were random events was estimated to be less than one part in 100,000.[34]

In the experiments, the decay of three atoms of ununoctium was observed. A half-life of 0.89 ms was calculated: 294Uuo decays into 290Uuh by alpha decay. Since there were only three nuclei, the half-life derived from observed lifetimes has a large uncertainty: 0.89−0.31+1.07 ms.[32]

The identification of the 294Uuo nuclei was verified by separately creating the putative daughter nucleus 290Uuh by means of a bombardment of 245Cm with 48Ca ions,

and checking that the 290Uuh decay matched the decay chain of the 294Uuo nuclei.[32] The daughter nucleus 290Uuh is very unstable, decaying with a half-life of 14 milliseconds into 286Uuq, which may undergo spontaneous fission or alpha decay into 282Uub, which will undergo spontaneous fission.[32]

Following the success in obtaining ununoctium, the discoverers have started similar experiments in the hope of creating element 120 from 58Fe and 244Pu.[35]

Naming

Element 118 is still called eka-radon, but before the 1960s it was also known as eka-emanation (for the old name for radon).[11] Only in 1979 the IUPAC published recommendations according to which the element started to be called ununoctium.[36] The name ununoctium is a systematic element name, used as a placeholder until it is confirmed by other research groups and the IUPAC decides on a name.

Before the retraction in 2002, the researchers from Berkeley had intended to name the element ghiorsium (Gh), after Albert Ghiorso (a leading member of the research team).[37] Several years later, when the Russian discoverers reported their synthesis in 2006, rumors appeared that they were planning on calling it after the place of the discovery, dubnadium (Dn) (very similar to the name of the 105th element, dubnium (Db)).[38] Nevertheless, during an interview with a Russian newspaper, the head of the Russian institute stated the team were considering two names for the new element, Flyorium in honour of Georgy Flyorov, the founder of the research institute; and Moscowium (also spelled Moskovium) (Russian: московий), in recognition of the Russian oblast in which Dubna lies.[39] He also stated that although the element was discovered as an American collaboration, who provided the californium target, the element should rightly be named in honour of Russia since the FLNR is the only facility in the world which can achieve this result.[40][41]

Characteristics

Nucleus stability and isotopes

There are no elements with an atomic number above 82 (after lead) that have stable isotopes. The stability of nuclei decreases with the increase in atomic number, such that all isotopes with an atomic number above 101 decay radioactively with a half-life of less than a day. Nevertheless, due to reasons not very well understood yet, there is a slight increased nuclear stability around elements 110–114, which leads to the appearance of what is known in nuclear physics as the "island of stability". This concept, proposed by UC Berkeley professor Glenn Seaborg, explains why superheavy elements last longer than predicted.[42] Ununoctium is radioactive and has half-life that appears to be less than a millisecond. Nonetheless, this is still longer than some predicted values,[43][44] thus giving further support to the idea of this "island of stability".[45]

Theoretical calculations done on the synthetic pathways for, and the half-life of, other isotopes have shown that some could be slightly more stable than the synthesized isotope 294Uuo, most likely 293Uuo, 295Uuo, 296Uuo, 297Uuo, 298Uuo, 300Uuo and 302Uuo.[43][46] Of these, 297Uuo might provide the best chances for obtaining longer-lived nuclei,[43][46] and thus might become the focus of future work with this element. Some isotopes with much more neutrons, such as some located around 313Uuo, could also provide longer-lived nuclei.[47]

Properties

Ununoctium is a member of the zero-valence elements that are called noble or inert gases. Consequently, it is expected that ununoctium will have similar physical and chemical properties to other members of its group, most closely resembling the noble gas above it in the periodic table, radon.[48] The members of this group are inert to most common chemical reactions (such as combustion, for example) because the outer valence shell is completely filled with eight electrons. This produces a stable, minimum energy configuration in which the outer electrons are tightly bound.[49] It is thought that similarly, ununoctium has a closed outer valence shell in which its valence electrons are arranged in a 7s2, 7p6 configuration.[19]

Following the periodic trend, it would be expected for ununoctium to be slightly more reactive than radon; but theoretical calculations have shown that it could be quite reactive for its "noble" labeling.[7] In addition to being far more reactive than radon, ununoctium may be even more reactive than elements 114 and 112.[19] The reason for the apparent enhancement of the chemical activity of element 118 relative to radon is an energetic destabilization and a radial expansion of the last occupied 7p subshell.[19][50] More precisely, considerable spin-orbit interactions between the 7p electrons with the inert 7s2 electrons, effectively lead to a second valence shell closing at element 114, and a significant decrease in stabilization of the closed shell of element 118.[19] It has also been calculated that ununoctium, unlike other noble gases, binds an electron with release of energy – or in other words, it exhibits positive electron affinity.[51][52][53]

Ununoctium is expected to have by far the largest polarizability of all elements before it in the periodic table, and almost twice of that of radon.[19] By extrapolating this to the other noble gases, it is expected that ununoctium has a boiling point between 320 and 380 K.[19] This is very different from the previously estimated values of 263 K[54] or 247 K.[55] Even given the large uncertainties of the calculations, it seems highly unlikely that element 118 would be a gas under standard conditions.[19][20] Because of its tremendous polarizability, ununoctium is expected to have an anomalously low ionization potential (similar to that of lead which is 70% of that of radon [6] and significantly smaller than that of element 114 [56]) and a standard state condensed phase.[19] Nevertheless, even if ununoctium is a monatomic gas under normal conditions, it would be one of the gaseous substances with the highest molecular masses – in fact, only UF

6 with a molecular mass of 352 would surpass it.

Compounds and uses

4 and RnF

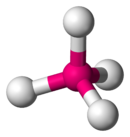

4 have a square planar configuration

4 is predicted to have a tetrahedral configuration

No compounds of ununoctium have been synthesized yet, but calculations on theoretical compounds have been performed since as early as 1964.[11] It is expected that if the ionization energy of the element will be high enough, it will be very hard to oxidize and therefore, the most common oxidation state to be 0 (as for other noble gases).[57]

Calculations on the dimeric molecule Uuo

2 showed a bonding interaction roughly equivalent to that calculated for Hg

2, and a dissociation energy of 6 kJ·mol−1, roughly 4 times of that of Rn

2.[19] But most strikingly, it was calculated to have a bond length shorter than in Rn

2 by 0.16 Å, which would be indicative of a significant bonding interaction.[19] On the other hand, the compound UuoH+ exhibits a dissociation energy (in other words proton affinity of Uuo) that is smaller than that of RnH+.[19]

The bonding between ununoctium and hydrogen in UuoH is very weak and can be regarded as a pure van der Waals interaction rather than a true chemical bond.[6] On the other hand, with highly electronegative elements, ununoctium seems to form more stable compounds than for example element 112 or element 114.[6] The stable oxidation states +2 and +4 have been predicted to exist in the fluorinated compounds UuoF

2 and UuoF

4.[58] This is a result of the same spin-orbit interactions that make ununoctium unusually reactive. For example, it was shown that the reaction of Uuo with F

2 to form the compound UuoF

2, would release an energy of 106 kcal/mol of which about 46 kcal/mol come from these interactions.[6] For comparison, the spin-orbit interaction for the similar molecule RnF

2 is about 10 kcal/mol out of a formation energy of 49 kcal/mol.[6] The same interaction stabilizes the tetrahedral Td configuration for UuoF

4, as opposed to the square planar D4h one of XeF

4 and RnF

4.[58] The Uuo-F bond will most probably be ionic rather than covalent, rendering the UuoF

n compounds non-volatile.[7][59] Unlike the other noble gases, ununoctium was predicted to be sufficiently electronegative to form a Uuo-Cl bond with chlorine.[7]

Since only three atoms of ununoctium have ever been produced, it currently has no uses outside of basic scientific research. It would constitute a radiation hazard if enough were ever assembled in one place.[60]

References

- ^ Oganesson. The Periodic Table of Videos. University of Nottingham. December 15, 2016.

- ^ Ritter, Malcolm (June 9, 2016). "Periodic table elements named for Moscow, Japan, Tennessee". Associated Press. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Nash, Clinton S. (2005). "Atomic and Molecular Properties of Elements 112, 114, and 118". Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 109 (15): 3493–3500. Bibcode:2005JPCA..109.3493N. doi:10.1021/jp050736o. PMID 16833687.

- ^ a b c Hoffman, Darleane C.; Lee, Diana M.; Pershina, Valeria (2006). "Transactinides and the future elements". In Morss; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- ^ a b c d e Smits, Odile; Mewes, Jan-Michael; Jerabek, Paul; Schwerdtfeger, Peter (2020). "Oganesson: A Noble Gas Element That Is Neither Noble Nor a Gas". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (52): 23636–23640. doi:10.1002/anie.202011976. PMC 7814676. PMID 32959952.

- ^ a b c d e f Han, Young-Kyu; Bae, Cheolbeom; Son, Sang-Kil; Lee, Yoon Sup (2000). "Spin–orbit effects on the transactinide p-block element monohydrides MH (M=element 113–118)". Journal of Chemical Physics. 112 (6): 2684. Bibcode:2000JChPh.112.2684H. doi:10.1063/1.480842. Cite error: The named reference "hydride" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e Kaldor, Uzi; Wilson, Stephen (2003). Theoretical Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements. Springer. p. 105. ISBN 978-1402013713. Retrieved 2008-01-18. Cite error: The named reference "Kaldor" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Guo, Yangyang; Pašteka, Lukáš F.; Eliav, Ephraim; Borschevsky, Anastasia (2021). "Chapter 5: Ionization potentials and electron affinity of oganesson with relativistic coupled cluster method". In Musiał, Monika; Hoggan, Philip E. (eds.). Advances in Quantum Chemistry. Vol. 83. pp. 107–123. ISBN 978-0-12-823546-1.

- ^ Oganesson, American Elements

- ^ Oganesson - Element information, properties and uses, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ a b c Grosse, A. V. (1965). "Some physical and chemical properties of element 118 (Eka-Em) and element 86 (Em)". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 27 (3). Elsevier Science Ltd.: 509–19. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(65)80255-X. Cite error: The named reference "60s" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Utyonkov, V. K.; Lobanov, Yu. V.; Abdullin, F. Sh.; Polyakov, A. N.; Sagaidak, R. N.; Shirokovsky, I. V.; Tsyganov, Yu. S.; et al. (2006-10-09). "Synthesis of the isotopes of elements 118 and 116 in the 249Cf and 245Cm+48Ca fusion reactions". Physical Review C. 74 (4): 044602. Bibcode:2006PhRvC..74d4602O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.74.044602. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Oganessian, Yuri Ts.; Rykaczewski, Krzysztof P. (August 2015). "A beachhead on the island of stability". Physics Today. 68 (8): 32–38. Bibcode:2015PhT....68h..32O. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2880. OSTI 1337838.

- ^ "Ununoctium". Columbia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

Pronounced yoo'nànŏk`tēàm

- ^ "Ununoctium". It's Elemental. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

Ununoctium is pronounced as oon-oon-OCT-i-em

- ^ M.E. Wieser (2006). "Atomic weights of the elements 2005 (IUPAC Technical Report)". 78 (11): 2051–2066. doi:10.1351/pac200678112051. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|joural=ignored (help) - ^ "The Top 6 Physics Stories of 2006". Discover Magazine. 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Clinton S. Nash (2005). "Atomic and Molecular Properties of Elements 112, 114, and 118". J. Phys. Chem. A. 109 (15): 3493–3500. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b It is debatable if the name of the group 'noble gases' will be changed if ununoctium is shown to be non-volatile

- ^ a b Robert Smolanczuk (1999). "Production mechanism of superheavy nuclei in cold fusion reactions". Physical Review C. 59 (5): 2634–2639. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ninov, Viktor (1999-05-27). "Observation of Superheavy Nuclei Produced in the Reaction of 86Kr with 208Pb". Physical Review Letters. 83 (6–9): 1104–1107. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1104. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Robert F. Service (1999-06-11). "Berkeley Crew Bags Element 118". Science. 284 (5421): 1751. doi:10.1126/science.284.5421.1751. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Public Affairs Department (2001-07-21). "Results of element 118 experiment retracted". Berkeley Lab. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Rex, Dalton (2002-12-19). "Misconduct: The stars who fell to Earth". Nature. 420: 728–729. doi:10.1038/420728a.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ Oganessian Yu.Ts.; et al. (2002). "Element 118: results from the first 249Cf + 48Ca experiment". Communication of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Text "publisher+JINR Publishing Department" ignored (help) - ^ "Livermore scientists team with Russia to discover element 118". Livermore press release. 2006-12-03. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Yu. Ts. Oganessian (2006-08-01). "Synthesis and decay properties of superheavy elements" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 78: 889–904. doi:10.1351/pac200678050889.

- ^ "Heaviest element made - again". Nature News. Nature (journal). 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Phil Schewe (2006-10-17). "Elements 116 and 118 Are Discovered". Physics News Update. American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rick Weiss (2006-10-17). "Scientists Announce Creation of Atomic Element, the Heaviest Yet". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b c d Oganessian, Yu. Ts. (2006-10-09). "Synthesis of the isotopes of elements 118 and 116 in the 249Cf and 245Cm+48Ca fusion reactions". Physical Review C. 74 (4): 044602. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.74.044602. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ununoctium". WebElements Periodic Table. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "Element 118 Detected, With Confidence". Chemical and Engineering news. 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

I would say we're very confident.

- ^ "A New Block on the Periodic Table" (PDF). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. April 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ J. Chatt (1979). "Recommendations for the Naming of Elements of Atomic Numbers Greater than 100". Pure Appl. Chem. 51: 381–384. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "Discovery of New Elements Makes Front Page News". Berkeley Lab Research Review Summer 1999. 1999. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ D. Trapp. "Origins of the Element Names-Names Constructed from other Words". Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "New chemical elements discovered in Russia`s Science City". 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ NewsInfo (2006-10-17). "Periodic table has expanded" (in Russian). Rambler. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|lang=and|language=specified (help) - ^ Yemel'yanova, Asya (2006-12-17). "118th element will be named in Russian" (in Russian). vesti.ru. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|lang=and|language=specified (help) - ^ Glenn D Considine; Peter H Kulik (2002). Van Nostrand's scientific encyclopedia (9 ed.). Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 9780471332305.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c P. Roy Chowdhury, C. Samanta, and D. N. Basu (2006). "α decay half-lives of new superheavy elements". Phys. Rev. C. 73: 014612. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yuri Oganessian (2007). "Heaviest nuclei from 48Ca-induced reactions". J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 34: R165–R242. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/34/4/R01. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "New Element Isolated Only Briefly". The Daily Californian. 2006-10-18. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b G. Royer, K. Zbiri, C. Bonilla (2004). "Entrance channels and alpha decay half-lives of the heaviest elements". Nuclear Physics A. 730: 355–376. doi:doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.010. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ S B Duarte, O A P Tavares, M Gonçalves, O Rodríguez, F Guzmán, T N Barbosa, F García and A Dimarco (2004). "Half-life predictions for decay modes of superheavy nuclei". J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 30: 1487–1494. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/30/10/014. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ununoctium - Uuo". Lenntech. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Bader, Richard F.W. "An Introduction to the Electronic Structure of Atoms and Molecules". McMaster University. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ the actual quote is: "The reason for the apparent enhancement of chemical activity of element 118 relative to radon is the energetic destabilization and radial expansion of its occupied 7p3/2 spinor shell"

- ^ Igor Goidenko, Leonti Labzowsky, Ephraim Eliav, Uzi Kaldor, and Pekka Pyykko¨ (2003). "QED corrections to the binding energy of the eka-radon (Z=118) negative ion". Physical Review A. 67: 020102(R). Retrieved 2008-01-18.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ephraim Eliav and Uzi Kaldor (1996-12-30). "Element 118: The First Rare Gas with an Electron Affinity". Physical Review Letters. 77 (27). Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Nevertheless, quantum electrodynamical corrections have been shown to be quite significant in reducing this affinity (by decreasing the binding in the anion Uuo- by 9%) thus confirming the importance of these corrections in superheavy atoms. See Pyykko

- ^ Glenn Theodore Seaborg (1994). Modern Alchemy. World Scientific. p. 172. ISBN 9810214405. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ N. Takahashi (2002). "Boiling points of the superheavy elements 117 and 118". Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 251 (2): 299–301. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Clinton S. Nash. "Spin-Orbit Effects, VSEPR Theory, and the Electronic Structures of Heavy and Superheavy Group IVA Hydrides and Group VIIIA Tetrafluorides. A Partial Role Reversal for Elements 114 and 118". J. Phys. Chem. A. 1999 (3): 402–410. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "Ununoctium: Binary Compounds". WebElements Periodic Table. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b Young-Kyu Han and Yoon Sup Lee (1999-02-09). "Structures of RgFn (Rg = Xe, Rn, and Element 118. n = 2, 4.) Calculated by Two-component Spin-Orbit Methods. A Spin-Orbit Induced Isomer of (118)F4". J. Phys. Chem. A. 103 (8): 1104–1108. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Kenneth S. Pitzer (1975). "Fluorides of radon and element 118". J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun.: 760b–761. doi:10.1039/C3975000760b.

{{cite journal}}: Text "accessdate-2008-01-18" ignored (help) - ^ "Ununoctium: Biological information". WebElements Periodic Table. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

See also

External links

- Discoverers' official website "ELEMENT 118: EXPERIMENTS on DISCOVERY"

- Chemistry-Blog: Independent analysis of 118 claim

- WebElements: Ununoctium

- Apsidium: Ununoctium - Moskowium

- It's Elemental: Ununoctium

- On the Claims for Discovery of Elements 110, 111, 112, 114, 116, and 118 (IUPAC Technical Report)