Meaning of life

The meaning of life is an elusive concept that has been the subject of much philosophical, scientific and theological speculation. [1][2][3][4]

It is often expressed in various related questions:[5]

- What is the meaning of life?[4][6][7][8][9][10]

- Why are we here?[1][11][12][13][14] What are we here for?[15]

- What is the origin of life?[16]

- What is the nature of life (and of reality itself)?[16][17]

- What is the purpose of, or in, (one's) life?[1][8][17][18][19]

- What is the significance of life?[19]

- What is meaningful or valuable in life?[20]

- What is the value of life?[21]

- What is the reason to live?[22] What are we living for?[15]

Some philosophers, notably the logical positivists, have asked questions like "What does the question 'What is the meaning of life?' mean?"[23] and also questioned whether it is a meaningful question.[24] Others have considered the question "If there are no objective values, then is life meaningless?"[25] Existentialists hold that meaning can be created by oneself, rejecting the nihilist view. Some, including Humanists, have aimed to develop an understanding of life that explains, regardless of how we came to be here, what we should do now that we are here.

In addition to the naturalistic hypotheses concerning the origin of life, consciousness and the universe offered by science, some philosophers and theologians posit a "watchmaker" or "intelligent designer" as the creator of the physical universe, mainly based on teleological and/or cosmological arguments. And others have considered the human need for some "higher" or "supernatural" ideal, for instance, in reference to Nietzsche's postulation of the "death" of God, Heidegger puts the problem as "If God as the suprasensory ground and goal of all reality is dead, if the suprasensory world of the Ideas has suffered the loss of its obligatory and above it its vitalizing and upbuilding power, then nothing more remains to which man can cling and by which he can orient himself."[26]

Religious answers to the question "What is the meaning of (my) life?" tend to include a certain moral demand[27] and to sooth the grief associated with death.[28] Mysticism focuses more on direct experience than religions generally do, and it has been associated with various movements. In general the view is that life is a happening, an unfolding, and the meaning of life is living a life in accordance with it.[29] Spirituality sees life as an inner-awakening or a discovery and transforming of one's understanding and insight,[7] and can be summarized as understanding the meaning of life, all of life and reality itself.[30]

Western philosophy

Ancient philosophy

Platonic view

Plato was one of the earliest and most influential thinkers of Western philosophy, most famous for his realist stance regarding the existence of universals. In the Theory of Forms he asserts that universals do not exist in the way that ordinary physical objects exist, but rather with a sort of ghostly or heavenly mode of existence. He describes the Form of the Good in his dialogue, The Republic, speaking through the character of Socrates. The Idea of the Good is the child or offspring (ekgonos) of the Good, the ideal or perfect nature of goodness, and so an absolute measure of justice.

For Plato the meaning of life is to attain the highest form of knowledge, which is the Idea (or Form) of the Good. It is from the Idea which all things that are good and just gain their usefulness and value. Humans have a duty to pursue the good, but no one can hope to do this successfully without philosophical reasoning, which allows for true knowledge.

Aristotelian view

Aristotle, an apprentice of Plato, was another of the earliest and most influential philosophers. He argued that ethical knowledge is not certain knowledge (like metaphysics and epistemology) but is general knowledge. Because it is not a theoretical discipline, he thought a person had to study and practice in order to become 'good'. Thus if a person were to become virtuous, he could not simply study what virtue is, he had to actually do virtuous activities. In order to do this, Aristotle had to first establish what was virtuous. "Every skill and every inquiry, and similarly, every action and choice of action, is thought to have some good as its object. This is why the good has rightly been defined as the object of all endeavor." (NE 1.1) Everything was done with some goal in mind, and that goal is 'good'.

But if action A is done with the goal B, the goal B would also have a goal, goal C. Goal C would also have a goal and this pattern would continue until something stopped the infinite regress. Aristotle's solution is the Highest Good, which is is desirable for its own sake. It is not desirable for the sake of some other good, and all other ‘goods’ desirable for its sake. This involves achieving eudaemonia, which is usually translated as "happiness" or alternatively "well-being" or "flourishing."

"What is the highest good in all matters of action? To the name, there is almost complete agreement; for uneducated and educated alike call it happiness, and make happiness identical with the good life and successful living. They disagree, however, about the meaning of happiness." (NE 1.4)

Cynic view

The Cynics were a Hellenistic school of philosophy that argued that the purpose of life was to live a life of Virtue in agreement with Nature. Happiness depends on being self-sufficient and a master of mental attitude, and suffering is caused by false judgments of value, which cause negative emotions and a vicious character.This meant rejecting all conventional desires for wealth, power, health, and fame, and by living a life free from all possessions.[31][32]

Cynics believe that as reasoning creatures, people could gain happiness by rigorous training and by living in way which was natural for humans. They believed that the world belonged equally to everyone, and that suffering was caused by false judgments of what was valuable and by the worthless customs and conventions which surrounded society.

Cyrenaic view

Cyrenaicism was one of the earliest Socratic schools, founded by Aristippus of Cyrene. Emphasizing one side only of the Socratic teaching, Aristippus asserted that happiness is one of the ends of moral action, and maintained that pleasure was the supreme good, creating a hedonistic view. He found bodily gratifications to be more intense and preferable to mental pleasures. Cyrenaics also deny that we should defer immediate gratification for the sake of long-term gain. In these respects they differ from the Epicureans.[33][34]

Epicurean view

Epicurus believed that the greatest good was to seek modest pleasures in order to attain a state of tranquility and freedom from fear (ataraxia) through knowledge, friendship, and living a virtuous and temperate life. It also involves the absence of bodily pain (aponia) through knowledge of the workings of the world and the limits of our desires. The combination of these states is supposed to constitute happiness in its highest form. He lauded the enjoyment of simple pleasures, by which he meant abstaining from bodily desires, such as sex and appetites, verging on asceticism.

When we say...that pleasure is the end and aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we are understood to do by some through ignorance, prejudice or wilful misrepresentation. By pleasure we mean the absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul. It is not by an unbroken succession of drinking bouts and of revelry, not by sexual lust, nor the enjoyment of fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs through which the greatest tumults take possession of the soul.[35]

Epicureanism rejects immortality and mysticism; it believes in the soul, but suggests that the soul is as mortal as the body. Epicurus rejected any possibility of an afterlife, while still contending that one need not fear death, because "Death is nothing to us; for that which is dissolved, is without sensation, and that which lacks sensation is nothing to us."[36]

Stoic view

Stoicism teaches that to live according to reason and virtue is to live in harmony with the divine order of the universe, which entails the recognition of the universal reason (logos) and essential value of all people. For Stoics, the meaning of life is to be free of suffering through apatheia (απαθεια) (Greek) understood as being objective or having "clear judgment", rather than simple indifference.

Stoicism's prime directives are virtue, reason, and natural law, and they seek the development of self-control and fortitude as a means of overcoming destructive emotions. The Stoics do not seek to extinguish emotions, only to avoid emotional troubles by developing clear judgment and inner calm through diligent practice of logic, reflection, and concentration.

The foundation of Stoic ethics is that good lies in the state of the soul itself, and it is exemplified by wisdom and self-control. Stoicism involves improving the individual’s spiritual well-being: "Virtue consists in a will which is in agreement with Nature."[36] This principle also applies to the realm of interpersonal relationships; "to be free from anger, envy, and jealousy".[36]

19th century philosophy

Utilitarian view

The origins of Utilitarianism are often traced back as far as Epicurus, but as a specific school of thought it is generally credited to Jeremy Bentham.[37] Bentham found the "nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure." From this he derived the rule of utility, that the good is whatever brings the greatest happiness to the greatest number of people. Later, after realizing that the formulation recognized two different and potentially conflicting principles, he dropped the second part and talked simply about "the greatest happiness principle."

Jeremy Bentham's foremost proponent was James Mill, a significant philosopher in his day and the father of John Stuart Mill. The younger Mill was educated according to Bentham's principles, including transcribing and summarising much of his father's work whilst still in his teens."[38] In his famous short work, Utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill argued that cultural, intellectual, and spiritual pleasures are of greater value than mere physical pleasure, because the former would be valued more highly by competent judges than the latter. A competent judge, according to Mill, is anyone who has experienced both the lower pleasures and the higher.[39]

Nihilist view

Nihilism rejects claims to knowledge and truth, and explores the meaning of an existence without knowable truth, and rather than merely insisting that values are subjective or even warrantless, nihilism declares that nothing is of value. From a nihilist point of view, morals are valueless and only hold a place in society as false ideals created by various forces. Though nihilism tends toward defeatism, one can find strength and reason for celebration in the varied and unique human relationships it explores.

Friedrich Nietzsche characterized nihilism as emptying the world and especially human existence of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, or essential value. He summed up the process of nihilism as "the devaluing of the highest values".[40] He also saw nihilism as a natural result of the idea that God is dead, and insisted that it was something to be overcome, by calling the nihilist's life-negating values in question and return meaning to the Earth.[2]

Martin Heidegger described nihilism as the movement whereby Being is forgotten and is wholly transformed into value, or in other words, the reduction of being to exchange value.[40]

Pragmatist view

Pragmatism is a school of philosophy which originated in the United States in the late 1800s, concerned largely by the issue of truth. Pragmatists believe that it is only through struggling with the surrounding environment that theories and data acquired by intelligent organisms have significance. Consequences like utility and practicality as vital components of truth, but pragmatism does not hold that just anything that is useful or practical should be regarded as true, or just anything that helps us to survive in the short-term; pragmatists argue that what should be taken as true is that which most contributes to the most human good over the longest course. In practice this means that theoretical claims should be tied to verification practices — i.e., that one should be able to make predictions and test them − and that ultimately the needs of humankind should guide the path of human inquiry.

Pragmatic philosophers suggest that rather than a truth about life, we should seek a useful understanding of life. William James argued that truth could be made but not sought.[41][42] To a pragmatist, the meaning of an individual's life can be discovered only through experience and the purposes which cause you to value it.

20th century philosophy

Existentialist views

There has been a wide variety in Existentialist thought. Arthur Schopenhauer offered a bleak answer to "What is the meaning of life?" by determining one's life as a reflection of one's will and the will (and thus life) as being an aimless, irrational, and painful drive. He saw salvation, deliverance, or escape from suffering in aesthetic contemplation, sympathy for others, and asceticism.[43][44] Søren Kierkegaard invented the term "leap of faith" and argued that life is full of absurdity and the individual must make his or her own values in an indifferent world. For Kierkegaard, an individual can have a meaningful life (or at least one free of despair) if the individual relates the self in an unconditional commitment to something finite, and devotes his or her life to the commitment despite the inherent vulnerability of doing so.[45]

Humanist views

According to Humanism, the human race came to be by reproducing in a progression of unguided evolution as an integral part of nature, which is self-existing.[46][47] Knowledge does not come from supernatural sources, rather it flows from human observation, experimentation, and rational analysis preferably utilizing the scientific method: the nature of the universe is what we discern it to be.[46] As are "values and realities", which are determined "by means of intelligent inquiry"[46] and "are derived from human need and interest as tested by experience", that is, by critical intelligence.[48][49] "As far as we know, the total personality is [a function] of the biological organism transacting in a social and cultural context."[47]

Humanists believe that human purpose is determined by humans, completely without supernatural influence; it is human personality (in the broadest sense) that is the purpose of a human's life, and this humanism seeks to develop and fulfill:[46] "Humanism affirms our ability and responsibility to lead ethical lives of personal fulfillment that aspire to the greater good of humanity."[48] Humanists seek enlightened self-interest and the common good for all people. The happiness of the individual is inextricably linked to the well-being of humanity as a whole, in part because we are social animals which find meaning in relationships, and because cultural progress benefits everybody who lives in that culture.[47][48]

Posthumanism and transhumanism (sometimes used as synonyms) are extensions of humanistic values. Like humanism, they propose that we should seek the advancement of humanity and of all life to the greatest degree feasible, with an emphasis on reconciling the views of Renaissance humanism to correspond more closely to the 21st century's concepts of technoscientific knowledge. These views insist that all living things be granted the basic option to inquire after their own personal or social "meaning(s) of life" (including meanings that human beings are currently incompetent to comprehend) as much as it is physically possible to do so, and no less.[50] They insist that the meaning of life is necessarily indefinite and ambiguous, and should be left to the philosophical inclinations of the individual; however there is a moral imperative common to all intelligent agents to improve their lives.

Logical positivist view

Of the meaning of life, Ludwig Wittgenstein and the logical positivists said: expressed in language, the question is meaningless. This is because "meaning of x" is a term in life usually conveying something regarding the consequences of x, or the significance of x, or that which should be noted regarding x, etc. So when "life" is used as "x" in the term "meaning of x", the statement becomes recursive and therefore nonsensical, or would simply refer to the obvious fact that the condition of life is essential for having meaning (in life).

In other words, things in a person's life can have meaning (importance), but a meaning of life itself, i.e., apart from those things, can't be discerned. In this context, a person's life is said to have meaning (significance to himself and others) in the form of the events throughout his life and the results of his life in terms of achievements, a legacy, family, etc. But to say that life itself has meaning is a misuse of language, since any note of significance or consequence is relevant only in life (to those living it), rendering the statement erroneous. Bertrand Russell, for example, wrote that although he found it impossible to believe that his distaste for torture was similar in nature to his distaste for broccoli, he nonetheless could find no satisfactory empirical method of proving this:[36]

When we try to be definite as to what we mean when we say that this or that is "the Good," we find ourselves involved in very great difficulties. Bentham's creed that pleasure is the Good roused furious opposition, and was said to be a pig's philosophy. Neither he nor his opponents could advance any argument. In a scientific question, evidence can be adduced on both sides, and in the end, one side is seen to have the better case — or, if this does not happen, the question is left undecided. But in a question as to whether this or that is the ultimate Good, there is no evidence either way; each disputant can only appeal to his own emotions, and employ such rhetorical devices as shall rouse similar emotions in others...Questions as to "values" — that is to say, as to what is good or bad on its own account, independently of its effects — lie outside the domain of science, as the defenders of religion emphatically assert. I think that in this they are right, but I draw the further conclusion, which they do not draw, that questions as to "values" lie wholly outside the domain of knowledge. That is to say, when we assert that this or that has "value," we are giving expression to our own emotions, not to a fact which would still be true if our personal feelings were different.[51]

Christian Views

The church has released a statement saying quite a simple thing; the meaning of life is to love.

Abrahamic religions

Jewish view

Jews believe the purpose of life is to serve God[52] and to prepare for the world to come[53] "Olam Haba".[54]

Judaism regards life as a precious gift from God; precious not only because it is a gift from God, but because, for humans, there is a uniqueness attached to that gift. Of all the creatures on Earth, humans are created in the image of God. Our lives are sacred and precious because we carry within us the Divine Image, and with it, unlimited potential.[55]

While Jewish thoughts are about elevating oneself in spirituality and connecting to God and trying to prepare for "Olam Haba", Jewish thought is to use this world, "Olam Hazeh," to help elevate ourself into the next.

Kabbalah, Jewish mysticism, takes it one step further. The Zohar states that the reason for life is to better one's soul. The soul descends to this world and endures the trials of this life so that it can reach a higher spiritual state upon its return to the source.

Christian view

Christians draw many of their beliefs from the Holy Bible, and believe that loving God is the meaning of life. In order to achieve this, one would ask for forgiveness of sins and receive God into their heart. Christianity believes in an eternal afterlife, and declares that it is an unearned gift from God through the love of Jesus Christ, which is to be received or forfeited by faith. (Ephesians 2:8–9; Romans 6:23; John 3:16–21; John 3:36).

Christians believe they are being tested and purified so that they may have a place of responsibility with Jesus in the eternal Kingdom to come. What a Christian does in this life will determine his place of responsibility with Jesus in the eternal Kingdom to come. Jesus encouraged Christians to be overcomers, so that they might share in the glorious reign with Him in the life to come: "To him who overcomes, I will give the right to sit with me on my throne, just as I overcame and sat down with my Father on his throne. He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches." (Rev 3:21–22)

The Bible states that it is God "in whom we live and move and have our being" (Acts 17:28), that to Fear God is the beginning of wisdom, and to depart from evil is the beginning of understanding (Job 28:28) and that "In Christ Jesus are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge" (Colossians 2:3). The Bible also says "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: Fear God, and keep his commandments: for this is the whole duty of man" (Ecclesiastes 12:13), and "Whether therefore ye eat, or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God." (Corinthians 10:31Template:Bibleverse with invalid book)

In one of the Westminster Articles (1647), the Shorter Catechism, the first question is "What is the chief end of man?", or in other words, 'What is man's main purpose?'. The answer, according to the Catechism is "Man's chief end is to glorify God and enjoy him forever." It goes on to explain that God requires of us to obey the moral law revealed to us, which proclaims that we must "love the Lord our God with all our heart, with all our soul, with all our strength, and with all our mind; and our neighbour as ourselves."[56]

Islamic view

To Muslims, life was created as a test, and how well one performs on this test will determine whether one finds a final home in Jannah (Heaven) or Jahannam (Hell).

In Islam the ultimate objective of man is to seek the pleasure of Allah by living in accordance with the Divine guidelines as stated in the Qur'an and the Tradition of the Prophet. The Qur'an clearly states that the whole purpose behind the creation of man was for glorifying and worshipping Allah:[57] "I only created jinn and man to worship Me" (Qur'an 51:56). Worshiping in Islam means to testify to the oneness of God in his lordship, names and attributes.

The esoteric Muslim view, generally held by Sufis, the universe exists only for God's pleasure. Creation works as a grand game,[58] with Allah as the greatest prize.[58]

Bahá'í view

The Bahá'í Faith, founded by Bahá'u'lláh, emphasizes the spiritual unity of all humankind.[59] According to Bahá'í teachings, religious history has unfolded through a series of God's messengers who brought teachings suited for the capacity of the people at their time, and whose fundamental purpose is the same.

The purpose of human life, say Bahá'ís, is spiritual growth. This is conceived almost as an organic process, like the development of a fetus, and continues after death. Neither a physical Heaven or Hell are present in the Bahá'í Faith. The Bahá'í teachings present "Heaven" and "Hell" to be states of spiritual nearness or remoteness to God, and that life continues in an afterlife through which the soul may progress infinitely through ever-more-exalted spiritual realms, eventually coming to stand before the Presence of God. The Bahá'í faith teaches that this process continues on in the spiritual afterlife, and not through a series of births and re-births as in reincarnation.[60][61][62]

Bahá'ís believe that while God's essence can never be fully fathomed, he can be understood through his "names and attributes." These are sometimes referred to as gems, and include such qualities as compassion, justice, knowledge, and wisdom. Education (especially of a spiritual nature) reveals the divine gems which God has placed within our souls.[63]

Dharmic religions and philosophy

Hindu views

Hinduism is an extremely diverse religion. Although some tenets of the faith are accepted by most Hindus, scholars have found it difficult to identify any doctrines with universal acceptance among all denominations.[64] Most Hindus believe that the spirit or soul—the true "self" of every person, called the ātman—is eternal.[65] The purusharthas are the canonical four ends or aims of human life.[66][67][68] These goals are, from lowest to highest importance: Kāma (sensual pleasure or love), Artha (wealth), Dharma (righteousness or morality) and Moksha (liberation from the cycle of reincarnation)

According to the monistic/pantheistic theologies of Hinduism (such as the Advaita Vedanta school), the ātman is ultimately indistinct from Brahman, the supreme spirit. Brahman is described as "The One Without a Second;" hence these schools are called "non-dualist."[69] The goal of life according to the Advaita school is to realize that one's atman (soul) is identical to Brahman, the supreme soul.[70] The Upanishads state that whoever becomes fully aware of the ātman as the innermost core of one's own self, realises their identity with Brahman and thereby reaches Moksha (liberation or freedom)[65][71][72] The notion of lila (literally, "play") refers to the idea of the universe as a cosmic game, and meaning as a "play of significance".[73] This "play", manifested in the million-formed inexhaustible richness of beings and events, is what gives us the key to the meaning of life.[74]

Other Hindu schools, such as the dualist Dvaita Vedanta and other bhakti schools, understand Brahman as a Supreme Being who possesses personality. On these conceptions, the ātman is dependent on Brahman, and the meaning of life is to achieve Moksha through love towards God and on God's grace.[71]

Jain view

Jainism is a religion originating in ancient India, its ethical system promotes self-discipline above all else. Through following the ascetic teachings of Jina, a human achieves enlightenment (perfect knowledge). Jainism divides the universe into living and non-living beings. Only when the non-living become attached to the living does suffering result. Therefore, happiness is the result of self-conquest and freedom from external objects. The meaning of life may then be said to be to use of the physical body to achieve self-realization and bliss.[75]

Jains believe that every human is responsible for his or her actions and all living beings have an eternal soul, jīva. Jains believe all souls are equal because they all possess the potential of being liberated and attaining Moksha. The Jain view of karma is that every action, every word, every thought produces, besides its visible, an invisible, transcendental effect on the soul.

Jainism includes strict adherence to ahimsa (or ahinsā), a form of nonviolence that goes far beyond vegetarianism. Jains refuse food obtained with unnecessary cruelty. Many practice a lifestyle similar to Veganism due to the violence of modern dairy farms, and others exclude root vegetables from their diets in order to preserve the lives of the plants from which they eat.[76]

Buddhist views

One of the central views in Buddhism is a nondual worldview, in which subject and object are the same, and the sense of doer-ship is illusionary. On this account, the meaning of life is to become enlightened as to the nature and oneness of the universe. According to the scriptures, the Buddha taught that in life there exists Dukkha, which is in essence sorrow/suffering, that is caused by desire and it can be brought to cessation by following the Noble Eightfold Path.

This teaching is called the Catvāry Āryasatyāni (Pali: Cattāri Ariyasaccāni), or the "Four Noble Truths".

- There is suffering (duhkha)

- There is a cause of suffering — craving (trishna)

- There is the cessation of suffering (nirvana)

- There is a way leading to the cessation of suffering — the Noble Eightfold Path

Theravada Buddhism promotes the concept of Vibhajjavada (Pali), literally "Teaching of Analysis." This doctrine says that insight must come from the aspirant's experience, critical investigation, and reasoning instead of by blind faith; however, the scriptures of the Theravadin tradition also emphasize heeding the advice of the wise, considering such advice and evaluation of one's own experiences to be the two tests by which practices should be judged. The Theravadin goal is liberation (or freedom) from suffering, according to the Four Noble Truths. This is attained in the achievement of Nibbana, or Unbinding which also ends the repeated cycle of birth, old age, sickness and death.

Mahayana Buddhist schools de-emphasize the traditional Theravada ideal of the release from individual Suffering (Dukkha) and attainment of Awakening (Nirvana). In Mahayana, the Buddha is seen as an eternal, immutable, inconceivable, omnipresent being. The fundamental principles of Mahayana doctrine are based around the possibility of universal liberation from suffering for all beings, and the existence of the transcendent Buddha-nature, which is the eternal Buddha essence present, but hidden and unrecognised, in all living beings.

Sikh view

The monastic Sikh religion was founded by Guru Nanak Dev, the term "sikh" means student, which denotes that followers will lead their lives forever learning. This system of religious philosophy and expression has been traditionally known as the Gurmat (literally the counsel of the gurus) or the Sikh Dharma. The followers of Sikhism are ordained to follow the teachings of the ten Sikh gurus, or enlightened leaders, as well as the holy scripture entitled the Gurū Granth Sāhib, which includes selected works of many philosophers from diverse socio-economic and religious backgrounds.

The Sikh Gurus tell us that salvation can be obtained by following various spiritual paths. Therefore, Sikhs do not have a monopoly on salvation: "The Lord dwells in every heart, and every heart has its own way to reach Him."[77] Sikhs do not consider they have an "exclusive" right to salvation. Sikhs believe that all people are equally important before God.[78] Sikhs balance their moral and spiritual values with the quest for knowledge, and they aim to promote a life of peace and equality but also of positive action.[79]

A key distinctive feature of Sikhism is a non-anthropomorphic concept of God, to the extent that one can interpret God as the Universe itself (pantheism). Sikhism thus sees life as an opportunity to understand this God as well as to discover the divinity which lies in each individual. While a full understanding of God is beyond human beings,[80] Nanak described God as not wholly unknowable. God is omnipresent (sarav viāpak) in all creation and visible everywhere to the spiritually awakened. Nanak stressed that God must be seen from "the inward eye", or the "heart", of a human being: devotees must meditate to progress towards enlightenment. Nanak emphasized the revelation through meditation, as its rigorous application permits the existence of communication between God and human beings.[80]

According to Sikhism, every creature has a soul. In death, the soul passes from one body to another until final liberation. The journey of the soul is governed by the karma of the deeds and actions we perform during our lives, and depending on the goodness or wrongdoings committed by a person in their life they will either be rewarded or punished in their next life. As the spirit of God is found in all life and matter, a soul can be passed onto other life forms, such as plants and insects - not just human bodies. A person who has evolved to achieve spiritual perfection in his lifetimes attains salvation – union with God and liberation from rebirth in the material world.

East Asian religions and philosophy

Taoist views

The Taoists cosmogony emphasizes the need for all sentient beings and all man to return to the primordial or to rejoin with the Oneness of the Universe by way of self-correction and self realization. It is the objective for all adherents to understand and be in tune with the ultimate truth.

Within the theology of Taoism, all man were originally a being called yuanling from Taiji and Tao, the meaning in life for the adherents is to realise the temporal nature of the existence, and all adherents are expected to practise, hone and conduct their mortal lives by way of Xiuzhen and Xiushen, as a preparation for the spiritual transcendence thereafter. "Only introspection can then help us to find our innermost reasons for living...the simple answer is here within ourselves."[81]

Shinto views

Shinto wants life to live, not to die. Shinto sees death as pollution and regards life as the realm where the divine spirit seeks to purify itself by rightful self-development. Shinto wants individual human life to be prolonged forever on earth as a victory of the divine spirit in preserving its objective personality in its highest forms. The presence of evil in the world, as conceived by Shinto, does not stultify the divine nature by imposing on divinity responsibility for being able to relieve human suffering while refusing to do so. The sufferings of life are the sufferings of the divine spirit in search of progress in the objective world.[28]

Confucian views

Confucianism recognizes human nature in accordance with the need for discipline and education. Because mankind is driven by both positive and negative influences, Confucianists see a goal in achieving the good nature through strong relationships and reasoning as well as minimizing the negative energy. This emphasis on normal living is seen in the Confucianist scholar Tu Wei-Ming's quote, "we can realize the ultimate meaning of life in ordinary human existence."[82]

Non-Abrahamic Iranian religions and philosophy

Zoroastrian view

Founded by Zoroaster, the Zoroastrianism message was that humans are responsible for the moral choices they make in a world of both good and evil options. For those who chose good actions, a blissful afterlife is promised, as well as a return to earth to continue life in a physical form. Those who chose evil actions would be doomed to a hellish afterlife.[83]

Scientific approaches

The primary aim of the scientific approach to the meaning of life is to describe the empirical facts about human existence. Claims that empirical science can shed light on issues such as the meaning of life are highly disputed within the scientific and philosophy-of-science communities, and have been from the very beginning of science. In spite of this, science has provided many theories about the origin of life, in the areas of abiogenesis (for the origins of biological life) and cosmogony (for the origins of the universe). Both of these areas are quite hypothetical; cosmogony because no existing physical model can accurately describe the very early universe (the instant of the Big Bang),[84] and abiogenesis because the environment of the young earth is still not accurately known, and even though the conditions and chemical processes that may have been present then have been reproduced in a laboratory, to produce organic molecules, those very conditions are still under debate.[85][86][87]

The true nature and origin of consciousness and the mind itself are also widely debated in science, and more specifically in relation to the hard problem of consciousness. Various theories relating to consciousness have been postulated,[88][89] including hypotheses of consciousness and spacetime,[90][91] electromagnetic theories of consciousness,[92][91][93] the Multiple Drafts Model,[94][95][96][97][98] the holonomic brain theory,[99] Orch-OR[100] and the many-minds interpretation.[101]

Origin and nature of biological life

The exact mechanisms by which biological life could have originated from inanimate matter are unknown, but multiple theories have been posited, including the contemporary RNA world hypothesis. Some scientists claim life began on Earth as a primeval soup, while others believe that a more "complete" form of life arrived on our planet through panspermia. The initial mechanisms by which primitive cells were formed notwithstanding, almost all scientific origin theories are contingent upon the evolution of traits through mutation and natural selection.[102] Near the end of the 20th century, equipped with insights from the gene-centered view of evolution, biologists such as George C. Williams, Richard Dawkins and David Haig, to name a few, have suggested that insofar as there may be a primary function to life, it may be the survival of genes; following this approach, success isn't measured in terms of the survival of species, but rather in terms of the successful replication of genes.[103]

Significance and value of life

Science may or may not be able to tell us what is of essential value in life, but some studies bear on related questions: Researchers in positive psychology (and earlier and less rigorously in humanistic psychology) study factors that lead to satisfaction in our lives. Social psychology examines factors that lead to infants thriving or failing to thrive, and in other areas of psychology questions of motivation, preference, and what people value. Economists have learned a great deal about what is valued in the marketplace; and sociology examines value at a social level using theoretical constructs such as value theory, norms, anomie, etc.

Scientific questions about an afterlife and the supernatural

Phenoma that seem to be unexplainable by present scientific understanding and seem to suggest the existence of an incorporeal higher consciousness and thus an afterlife, are often explained away or neglected by many scientists, on grounds of having been misinterpreted or being unsupported by existing evidence.[104] Such phenomena may often be described as "paranormal", "supernatural" or "spiritual", several examples include near-death experiences, telepathy, psychokinesis, precognition and remote viewing.

In hopes of proving the existence of these phenomena, parapsychologists have orchestrated various experiments. Meta-analyses of these experiments indicate that the effect size (though very small) has been consistent across time and experimental designs, resulting in an overall statistical significance.[105][106][107][108][109] Although some critical analysts feel that parapsychological study is scientific, they are not satisfied with its experimental results.[110][111] Skeptical reviewers contend that apparently successful experimental results are more likely due to sloppy procedures, poorly trained researchers, or methodological flaws than to actual effects.[112][113][114][115]

Popular views

"What is the meaning of life?" is a question many people ask themselves at some point during their lives, most in the context "What is the purpose of life?"[8] Here are some of the life goals people choose, and some of their beliefs on what the purpose of life is:

...to have life

- ...to survive,[116] that is, to live as long as possible,[117] including pursuit of immortality (through scientific means).[118]

...to live forever[118] or die trying.[119] - ...to evolve.[120][121]

- ...to replicate, to reproduce.[10] "The 'dream' of every cell is to become two cells."[122][123][124][125]

- ...to be fruitful and multiply.[126] (Genesis 1:28)

...to seek wisdom and knowledge

- ...to expand one's perception of the world.[127]

- ...to follow the clues and walk out the exit.[128]

- ...to learn as many things as possible in life.[129]

...to know as much as possible about as many things as possible.[130] - ...to know and master the world.[131][132]

...to know and master nature.[133] - ...to seek wisdom and knowledge and to tame the mind, as to avoid suffering caused by ignorance and find happiness.[134]

- ...to face our fears and accept the lessons life offers us.[135]

- ...to understand the mystery of God.[135]

- ...to know God.[136]

- ...to know oneself, know others, and know the will of heaven.[137]

- ...to find the meaning of life.[138]

...to find the purpose of life.[139]

...to find a reason to live.[140] - ...to resolve the imbalance of the mind by understanding the nature of reality.[141]

...to do good, to do the right thing

- ...to leave the world a better place than you found it.[10]

...to do your best to leave every situation better than you found it.[10] - ...to benefit others.[15]

- ...to give more than you take.[10]

- ...to end suffering.[142][143][144]

- ...to create equality.[145][146][147]

- ...to challenge oppression.[148]

- ...to distribute wealth.[149][150]

- ...to be generous.[151][152]

- ...to contribute to the well-being and spirit of others.[153]

- ...to help others,[1][152] to help one another.[154]

...to take every chance to help another while on your journey here.[10] - ...to be creative and innovative.[153]

- ...to forgive.[10]

...to accept and forgive human flaws.[155] - ...to be emotionally sincere.[156]

- ...to be responsible.[156]

- ...to be honorable.[156]

- ...to seek peace.[156]

...to pursue a certain form of fulfillment, perfection or success

- ...to chase dreams.[10]

...to live one's dreams.[127] - ...to seek beauty in all its forms.[10]

- ...to seek happiness[157][158] and flourish.[1]

- ...to expand one's potential in life.[127]

- ...to be a true authentic human being.[159]

- ...to become the person you've always wanted to be.[160]

- ...to become the best version of yourself.[5]

- ...to rule the world.[161]

- ...to fill the Earth and subdue it.[126] (Genesis 1:28)

- ...to spend it for something that will outlast it.[156]

- ...to matter: to count, to stand for something, to have made some difference that you lived at all.[156]

- ...to keep one's soul pure.[156]

- ...to be able to put the whole of oneself into one's feelings, one's work, one's beliefs.[156]

- ...to follow our destiny.[135]

...to submit to our destiny.[161] - ...to create your own destiny.[162]

...to love, to feel, to feel joy in living

- ...to love more.[10]

- ...to love those who mean the most. Every life you touch will touch you back.[10]

- ...to treasure every enjoyable sensation one has.[10]

- ...to have fun.[153]

...to enjoy life.[135]

...to seek pleasure.[156] - ...to be compassionate.[156]

- ...to be moved by the tears and pain of others, and try to help them out of love and compassion.[10]

- ...to love others as best we possibly can.[10]

- ...to love something bigger, greater, and beyond ourselves, something we did not create or have the power to create, something intangible and made holy by our very belief in it.[10]

- ...to love God.[136]

One should not search for the meaning of life

- The answer to the meaning of life is too profound to be known and understood.[141]

- You will never live if you are looking for the meaning of life.[10]

- The meaning of life is to forget about the search for the meaning of life.[10]

Life has no meaning

- Life or human existence has no real meaning or purpose because human existence occurred out of a random chance in nature, and anything that exists by chance has no intended purpose.[141]

- Life has no meaning, but as humans we try to associate a meaning or purpose so we can justify our existence.[10]

- There is no point in life, and that is exactly what makes it so special.[10]

- Life is a bitch and then you die.[160]

Life sucks and in the end you die.[148]

Popular culture treatments

The mystery of life and its meaning is an often recurring subject in popular culture, featured in entertainment media and various forms of art, and more specifically in music, literature and visual arts, for example:

- in songs like The Offspring's "The Meaning of Life", Nas' "Life's a Bitch", Kiss' "Reason to Live", George Harrison's "All Things Must Pass" and "What Is Life", Frank Sinatra's "That's Life", Eric Idle's "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life", Evanescence's "Bring Me To Life" and "Sweet Sacrifice", Nelly Furtado's "All Good Things (Come To An End)" and "In God's Hands", 30 Seconds to Mars' "A Beautiful Lie", Good Charlotte's "I Just Wanna Live" and "The Chronicles of Life and Death" and Linkin Park's "In the End" and "Breaking the Habit";

- in books like Anthony C. Grayling's The Meaning of Things, Viktor Frankl's Man's Search for Meaning, Robert Nozick's Philosophical Explanations and The Examined Life, Ken Wilber's Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, Julian Baggini's What's it All About? Philosophy and the Meaning of Life, Rick Warren's The Purpose Driven Life, Norman O. Brown's Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytic Meaning of History, Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West, Daniel Dennett's Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life, Richard Dawkins' Unweaving the Rainbow and River out of Eden and Alister McGrath's Dawkins' God: Genes, Memes, and the Meaning of Life;

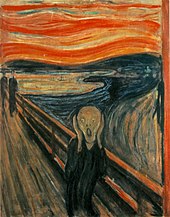

- and in paintings like Paul Gauguin's Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, Edvard Munch's The Scream, John Martin's The End of the World, Hieronymus Bosch's Ascent of the Blessed, Hans Memling's The Last Judgment triptych and Thomas Cole's The Voyage of Life series.

-

The Voyage of Life

Childhood -

The Voyage of Life

Youth -

The Voyage of Life

Manhood -

The Voyage of Life

Old Age

- In Douglas Adams' popular comedy book series The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything has the numeric solution of 42, which was derived over seven and a half million years by a giant supercomputer called Deep Thought. After much confusion from the descendants of his creators, Deep Thought explains that the problem is that they do not know the Ultimate Question[1], and they would have to build an even more powerful computer to determine what that is. This computer is revealed to be Earth, which, after 10 million years of calculating, is destroyed to make way for a galactic bypass moments before it finishes calculations.[163][9][14] In Life, the Universe and Everything, it is confirmed that 42 is indeed the Ultimate Answer, and that it is impossible for both the Ultimate Answer and the Ultimate Question to be known about in the same universe, as they will cancel each other out and take the universe with them, to be replaced by something even more bizarre, and that this may have already happened.[164] Subsequently, in the hopes that his subconscious holds the question, Arthur Dent guesses at the question, and comes up with "What do you get when you multiply six by nine?" This was in fact not the Ultimate Question, as the arrival of the Golgafrinchans on prehistoric Earth had disrupted the computation process.[165] However, Dent, Fenchurch, and a dying Marvin did see God's Final Message to His Creation "We apologise for the inconvenience".[166]

- In Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, there are several allusions to the meaning of life. In "Part VI B: The Meaning of Life" a cleaning lady explains "Life's a game, you sometimes win or lose" and later a waiter describes his personal philosophy "The world is a beautiful place. You must go into it, and love everyone, not hate people. You must try and make everyone happy, and bring peace and contentment everywhere you go."[167] At the end of the film, we can see Michael Palin being handed an envelope, he opens it, and provides the viewers with 'the meaning of life': "Well, it's nothing very special. Uh, try to be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try to live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations."[167][168][169]

- In The Simpsons episode "Homer the Heretic", a representation of God tells Homer what the meaning of life is, but as usual the one who really wanted to know (the viewer) is left disappointed. The dialogue goes as follows:

- Homer: God, what's the meaning of life?

- God: Homer, I can't tell you that.

- Homer: Why not?

- God: You'll find out when you die.

- Homer: Oh, I can't wait that long.

- God: You can't wait 6 months?

- Homer: No, tell me now...

- God: Oh, OK... The meaning of life is...

- At this point, the credits music starts and the show ends. The writer's original idea was that a commercial would come after this scene and before the credits, thus having the commercial interrupt God's explanation to humorous effect.

- At the end of The Matrix Revolutions, Agent Smith concludes that "the purpose of life is to end." He is determined to move that purpose along for Neo.[170]

- The crew of the Red Dwarf is captured in episode 2 of season 5 by a powerful being called The Inquisitor, a self-repairing simulant who survived until the end of time and, coming to the conclusion that there is no God and no afterlife, decided that the only point of life was to make something of yourself. The Inquisitor then proceeds to put each of the Red Dwarf misfits on trial and forces them to justify their existence. Failure to do so will result in a sentence of being erased from history.

- In Peanuts, Charlie Brown explains he thinks the purpose of life is to make others happy, to which Lucy responds that she doesn't think she is making anyone happy, and—more importantly—no one is making her happy, so someone isn't doing their job, eventually she asks him "You say we're put on this earth to make others happy? ... What are the others put here for?"[171] On several other occasions, Charlie has asserted several other things in relation to life and its meaning: "In the book of life, the answers aren't in the back."[171][172], "That's the secret to life... replace one worry with another."[171][173], "Happiness is anyone and anything at all that's loved by you."[174] and "Life is like an ice cream cone...you have to lick it one day at a time."[175] Lucy has also declared "Life is too short to waste it listening to some person who doesn't know when to shut up! Time is too valuable!"[171] and "All you really need is love, but a little chocolate now and then doesn't hurt."[171][176]

- In Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey, Bill and Ted end up meeting God. Before being admitted into his presence, St. Peter (billed as The Gatekeeper on IMDb) asks them what the meaning of life is, and they reply with the lyrics to the song "Every Rose Has Its Thorn" by Poison.

- The Alchemist and the movie City Slickers both present the meaning of life as an individual journey to find one's own "path". In this context, the "path", similar to what is defined in Buddhism as the 4th Noble Truth: the Eightfold Path, is best explained simply as the overall way one chooses to lead their life.

- In A Man Without a Country, author Kurt Vonnegut sums up life with the words: "We're all here to fart around. Don't let anyone tell you any different!". In Vonnegut's novel Breakfast of Champions, "To be the eyes and ears and conscience of the Creator of the Universe, you fool." is Kilgore Trout's unwritten reply to the question "What is the purpose of life?"

- A quotation by Anton Chekhov states "You ask "What is life?" That is the same as asking "What is a carrot?" A carrot is a carrot and we know nothing more."[177]

- In William Shakespeare's Hamlet, Prince Hamlet states: "To be or not to be, that is the question."

- In Dune, a seminal science fiction novel by Frank Herbert, the meaning of life is defined as "not a question to be answered, but a reality to be experienced".

See also

Origin and nature of life and reality

|

Significance of lifeValue in and of life

Purpose of lifeMiscellaneous

|

References

- ^ a b c d e f Julian Baggini (September 2004). What's It All About? Philosophy and the Meaning of Life. USA: Granta Books. ISBN 1862076618.

- ^ a b Bernard Reginster (2006). The Affirmation of Life: Nietzsche on Overcoming Nihilism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674021991.

- ^ Julian Young (2003). The Death of God and the Meaning of Life. Routledge. ISBN 0415307902.

- ^ a b Jonathan Westphal (1998). Philosophical Propositions: An Introduction to Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 0415170532.

- ^ a b Matthew Kelly (2005). The Rhythm of Life: Living Every Day with Passion and Purpose. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743265106.

- ^ Robert Nozick (1981). Philosophical Explanations. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674664795.

- ^ a b Albert Jewell (2003). Ageing, Spirituality and Well-Being. Jessica Kingsley

Publishers. ISBN 184310167X.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 17 (help) - ^ a b c "Question of the Month: What Is The Meaning Of Life?". Philosophy Now. Issue 59. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ a b Glenn Yeffeth (2005). The Anthology at the End of the Universe: Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. BenBella Books, Inc. ISBN 1932100563.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s David Seaman (2005). The Real Meaning of Life. New World Library. ISBN 1577315146.

- ^ Ronald F. Thiemann; William Carl Placher (1998). Why Are We Here?: Everyday Questions and the Christian Life. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1563382369.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dennis Marcellino (1996). Why Are We Here?: The Scientific Answer to this Age-old Question (that you don't need to be a scientist to understand). Lighthouse Pub. ISBN 0945272103.

- ^ F. Homer Curtiss (2003). Why Are We Here. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0766138992.

- ^ a b William B. Badke (2005). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Meaning of Everything. Kregel Publications. ISBN 0825420695.

- ^ a b c Hsuan Hua (2003). Words of Wisdom: Beginning Buddhism. Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. ISBN 0881393029.

- ^ a b Paul Davies (March 2000). The Fifth Miracle: The Search for the Origin and Meaning of Life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-86309-X. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ a b Charles Christiansen; Carolyn Manville Baum; Julie Bass-Haugen (2005). Occupational Therapy: Performance, Participation, and Well-Being. SLACK Incorporated. p. 680. ISBN 1556425309.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rick Warren (2002). The Purpose Driven Life: What on Earth Am I Here For?. Zondervan. ISBN 0310255252.

- ^ a b Jiddu Krishnamurti (2001). What Are You Doing With Your Life?. Krishnamurti Foundation of America. ISBN 188800424X.

- ^ Puolimatka, Tapio (2002). "Education and the Meaning of Life" (PDF). Philosophy of Education. University of Helsinki. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stan Van Hooft (2004). Life, Death, and Subjectivity: Moral Sources in Bioethics. Rodopi. p. 247. ISBN 9042019123.

- ^ Russ Shafer-Landau; Terence Cuneo (2007). Foundations of Ethics: An Anthology. Blackwell Publishing. p. 520. ISBN 1405129514.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Richard Taylor (January 1970). Good and Evil. Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. "The Meaning of Life" (Chapter 5). ISBN 0026166909.

- ^ Wohlgennant, Rudolph. (1981). "Has the Question about the Meaning of Life any Meaning?" (Chapter 4). In E. Morscher, ed., Philosophie als Wissenschaft.

- ^ McNaughton, David (August 1988). Moral Vision: An Introduction to Ethics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. "Moral Freedom and the Meaning of Life" (Section 1.5). ISBN 0631159452.

- ^ Heidegger, "The Word of Nietzsche," 61.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy (2007). On Life and Essays on Religion. READ BOOKS. p. 448. ISBN 1406742090.

- ^ a b J. W. T. Mason (2002). The Meaning of Shinto. Trafford Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 1412245516.

- ^ Richard H. Jones (2004). Mysticism and Morality: A New Look at Old Questions. Lexington Books. p. 432. ISBN 0739107844.

- ^ Theresa King (1992). The Spiral Path: Explorations in Women's Spirituality. Yes International Publishers. ISBN 0936663138.

- ^ Kidd, I., "Cynicism," in The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy. (ed. Urmson and Rée), Routledge. (2005)

- ^ Long, A. A., "The Socratic Tradition: Diogenes, Crates, and Hellenistic Ethics," in The Cynics: The Cynic Movement in Antiquity and Its Legacy. (ed. Branham and Goulet-Cazé), University of California Press, (1996).

- ^ "Cyrenaics." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The University of Tennessee At Martin. 4 Nov. 2007 <http://www.iep.utm.edu/>.

- ^ "The Cyrenaics and the Origin of Hedonism." Hedonism.org. BLTC. 4 Nov. 2007 <http://www.hedonism.org>.

- ^ Epicurus, "Letter to Menoeceus", contained in Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book X

- ^ a b c d Bertrand Russell (1946). A History of Western Philosophy, New York: Simon and Schuster; London: George Allen and Unwin

- ^ Rosen, Frederick (2003). Classical Utilitarianism from Hume to Mill. Routledge, pg. 28. ISBN 0415220947 "It was Hume and Bentham who then reasserted most strongly the Epicurean doctrine concerning utility as the basis of justice."

- ^ Mill, John Stuart. 'On Liberty', ed. Himmelfarb. Penguin Classics, 1974, Ed.'s introduction, p.11.

- ^ John Stuart Mill (1863). Utilitarianism.

- ^ a b Jérôme Bindé (2004). The Future Of Values: 21st-Century Talks. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1571814426.

- ^ William James (1909). The Meaning of Truth. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-138-6.

- ^ Walter Robert Corti (1976). The Philosophy of William James. Meiner Verlag. ISBN 3787303529.

- ^ Dale Jacquette (1996). Schopenhauer, Philosophy, and the Arts. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521473888.

- ^ Durno Murray (1999). Nietzsche's Affirmative Morality. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3110166011.

- ^ Amy Laura Hall (2002). Kierkegaard and the Treachery of Love. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521893119.

- ^ a b c d "[[Humanist Manifesto I]]] [http://www.americanhumanist.org/about/manifesto1.html". American Humanist Association. 1933. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c "[[Humanist Manifesto II]]] [http://www.americanhumanist.org/about/manifesto2.html". American Humanist Association. 1973. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c "[[Humanist Manifesto III]]] [http://www.americanhumanist.org/3/HumandItsAspirations.php". American Humanist Association. 2003. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "[[A Secular Humanist Declaration]]] [http://www.secularhumanism.org/index.php?section=main&page=declaration". Council for Democratic and Secular Humanism (now the Council for Secular Humanism). 1980. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Nick Bostrom (2005). "Transhumanist Values". Oxford University. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ^ Bertrand Russell (1961). Science and Ethics

- ^ Dan Cohn-Sherbok (2003). Judaism: History, Belief, and Practice. Routledge. p. 512. ISBN 0415236614.

- ^ Abraham Joshua Heschel (2005). Heavenly Torah: As Refracted Through the Generations. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826408028.

- ^ Wilfred Shuchat (2006). The Garden of Eden & the Struggle to Be Human: According to the Midrash Rabbah. Devora Publishing. p. 584. ISBN 1932687319.

- ^ Randolph L. Braham (1983). Contemporary Views on the Holocaust. Springer. ISBN 089838141X.

- ^ "The Westminster Shorter Catechism". Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Ian Markham; İbrahim Özdemir (2005). Globalization, Ethics and Islam: The Case of Bediuzzaman Said Nursi. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0754650154.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Abdullah Yusuf Ali (2000). The Holy Qur'an. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1853267821.

- ^ "Bahaism." The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, vol. Fourth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2007

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Bahá'u'lláh (1873). The Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book [1]. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0853989990.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Bahá'u'lláh (1862). The Kitáb-i-Íqán: The Book of Certitude [2]. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 1931847088.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Bahá'u'lláh (1991) [1856-63]. The Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys [3]. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-227-9.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Bahá'u'lláh (2002). Gems of Divine Mysteries [4]. Haifa, Israel: Bahá'í World Centre. ISBN 0-85398-975-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ a b Template:Harvard reference

- ^ For dharma, artha, and kama as "brahmanic householder values" see: Flood (1996), p. 17.

- ^ For the Dharma Śāstras as discussing the "four main goals of life" (dharma, artha, kāma, and moksha) see: Hopkins, p. 78.

- ^ For definition of the term पुरुष-अर्थ (puruṣa-artha) as "any of the four principal objects of human life, i.e. धर्म, अर्थ, काम, and मोक्ष" see: Apte, p. 626, middle column, compound #1.

- ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ a b Template:Harvard reference

- ^ See also the Vedic statement "ayam ātmā brahma" (This Atman is Brahman).

- ^ Richard Schechner (2002). Performance Studies: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 304. ISBN 0415146208.

- ^ Thomas Merton (1995). Thoughts on the East. New Directions Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 0811212939.

- ^ Shah, Natubhai. Jainism: The World of Conquerors. Sussex Academic Press, 1998.

- ^ "Viren, Jain" (PDF). RE Today. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Daljeet Singh (1971). Guru Tegh Bahadur. Language Dept., Punjab. p. 195.

- ^ Jon Mayled (2002). Modern World Religions: Sikhism. Harcourt Heinemann. p. 62. ISBN 0435336266.

- ^ The Sikh Coalition

- ^ a b Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 252. ISBN 0-87196-129-6.

- ^ Ming-Dao Deng (1990). Scholar Warrior: An Introduction to the Tao in Everyday Life. HarperCollins.

- ^ Tu, Wei-Ming. Confucian Thought: Selfhood as Creative Transformation. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985.

- ^ Muesse, Mark. Religions of the Axial Age: An Approach to the World's Religions. Lectures at Rhodes College.

- ^ Brian Greene (2004). The Fabric of the Cosmos. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 272. ISBN 0375727205.

- ^ Noam Lahav (1998). Biogenesis: Theories of Life's Origin. Oxford University Press US. p. 368. ISBN 0195117557.

- ^ André Brack (1998). The Molecular Origins of Life: Assembling Pieces of the Puzzle. Cambridge University Press. p. 428. ISBN 0521564751.

- ^ Günter Wächtershäuser (25 Aug 2000). "Origin of Life: Life as We Don't Know It", Science, 289 (5483) pp. 1307-1308.

- ^ Paul M. Churchland (1989). A Neurocomputational Perspective: The Nature of Mind and the Structure of Science. MIT Press. p. 321. ISBN 0262531062.

- ^ Harvey Whitehouse (2001). The Debated Mind: Evolutionary Psychology Versus Ethnography. Berg Publishers. p. 224. ISBN 1859734278.

- ^ John D. Barrow; Paul C. W. Davies; Charles L. Harper (2004). Science and Ultimate Reality: Quantum Theory, Cosmology, and Complexity. Cambridge University Press. p. 742. ISBN 052183113X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mae-Wan Ho (1998). The Rainbow and the Worm: The Physics of Organisms. World Scientific. p. 304. ISBN 9810234279.

- ^ J. McFadden (2002) "Synchronous Firing and Its Influence on the Brain's Electromagnetic Field: Evidence for an Electromagnetic Field Theory of Consciousness". Journal of Consciousness Studies 9 (4) pp. 23-50.

- ^ R. Buccheri; V. Di Gesù; Metod Saniga (2000). Studies on the Structure of Time: From Physics to Psycho(patho)logy. Springer. p. 420. ISBN 030646439X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Daniel Clement Dennett (1991). Consciousness Explained. Little, Brown and Co. p. 511. ISBN 0316180661.

- ^ Ned Joel Block (2007). Consciousness, Function, and Representation. MIT Press. p. 636. ISBN 0262026031.

- ^ Andrew Brook; Kathleen Akins (2005). Cognition and the Brain: The Philosophy and Neuroscience Movement. Cambridge University Press. p. 440. ISBN 0521836425.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stanislas Dehaene (2001). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Consciousness. MIT Press. p. 249. ISBN 0262541319.

- ^ Jeffrey Alan Gray (2004). Consciousness: Creeping Up on the Hard Problem. Oxford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0198520905.

- ^ Mohsen Kermanshahi (May 2007). Universal Theory: A Model for the Theory of Everything. Universal Publishers. p. 268. ISBN 1581129432.

- ^ Alexandra Bruce (2005). Beyond the Bleep: The Definitive Unauthorized Guide to What the Bleep Do We Know!?. The Disinformation Company. p. 288. ISBN 1932857222.

- ^ David Bohm; Basil J. Hiley (1993). The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory. Routledge. p. 397. ISBN 0415065887.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Charles Darwin (1859). On the Origin of Species.

- ^ Richard Dawkins (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. p. 224. ISBN 019857519X.

- ^ "Skeptics Dictionary Alphabetical Index Abracadabra to Zombies". skepdic.com. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ Radin, Dean (1997). The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0062515020.

- ^ Dunne, Brenda (2003). "Does psi exist? Replicable evidence for an anomalous process of information transfer". Journal of Scientific Exploration. 17 (2): 207–241. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dunne, Brenda J. (1985). "On the quantum mechanics of consciousness, with application to anomalous phenomena". Foundations of Physics. 16 (8): 721–772. doi:10.1007/BF00735378. ISSN (Print) 1572-9516 (Online) 0015-9018 (Print) 1572-9516 (Online). Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bösch H, Steinkamp F, Boller E (2006). "Examining psychokinesis: the interaction of human intention with random number generators—a meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (4): 497–523. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.4.497. PMID 16822162.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Radin, D.; Nelson, R.; Dobyns, Y.; Houtkooper, J. (2006). "Reexamining psychokinesis: comment on Bösch, Steinkamp, and Boller". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (4): 529–32, discussion 533–37. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.4.529. PMID 16822164.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alcock, James E. (2003). "Give the Null Hypothesis a Chance" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 10 (6–7): 29–50. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hyman, Ray (1995). "Evaluation of the program on anomalous mental phenomena". The Journal of Parapsychology. 59 (1). Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ Akers, C. (1986). "Methodological Criticisms of Parapsychology, Advances in Parapsychological Research 4". PesquisaPSI. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Child, I.L. (1987). "Criticism in Experimental Parapsychology, Advances in Parapsychological Research 5". PesquisaPSI. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wiseman, Richard (1996). "Exploring possible sender-to-experimenter acoustic leakage in the PRL autoganzfeld experiments - Psychophysical Research Laboratories". The Journal of Parapsychology. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lobach, E. (2004). "The Invisible Gaze: Three Attempts to Replicate Sheldrake's Staring Effects" (PDF). Proceedings of the 47th PA Convention. pp. 77–90. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lopez, Mike (September 22, 1999). "Episode III: Relativism? A Jedi craves not these things". The Michigan Daily. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ Lovatt, Stephen C. (2007). New Skins for Old Wine. Universal Publishers. pp. The Meaning of Life. ISBN 1581129602.

- ^ a b Raymond Kurzweil; Terry Grossman (2004). Fantastic Voyage: Live Long Enough to Live Forever [5]. Holtzbrinck Publishers. ISBN 1-57954-954-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Bryan Appleyard (2007). How to Live Forever Or Die Trying: On the New Immortality. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743268687.

- ^ Cameron, Donald (2001). The Purpose of Life. Woodhill Publishing. ISBN 0-9540291-0-0.

- ^ Wayne, Larry. "Expanding The Oneness". SelfGrowth.com. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nick Lane (2005). Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192804812.

- ^ Kenneth M. Weiss; Anne V. Buchanan (2004). Genetics and the Logic of Evolution. Wiley-IEEE. ISBN 0471238058.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jennifer Ackerman (2001). Chance in the House of Fate: A Natural History of Heredity. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 0618219099.

- ^ Boyce Rensberger (1996). Life Itself: Exploring the Realm of the Living Cell. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195125002.

- ^ a b Thomas Patrick Burke (2004). The Major Religions: An Introduction with Texts. Blackwell Publishing. p. 400. ISBN 140511049X.

- ^ a b c Roger Ellerton PhD, CMC (2006). Live Your Dreams... Let Reality Catch Up: NLP and Common Sense for Coaches, Managers and You. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1412047099.

- ^ Chris Grau (2005). Philosophers Explore the Matrix. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195181074.

- ^ John M. Cooper; D. S. Hutchinson (1997). Plato: Complete Works. Hackett Publishing. p. 1808. ISBN 0-87220-349-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John E. Findling, Frank W. Thackeray (2001). Events That Changed the World Through the Sixteenth Century. Greenwood Press. p. 240. ISBN 0313290792.

- ^ Peter Harrison (2001). The Bible, Protestantism, and the Rise of Natural Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 326. ISBN 0521000963.

- ^ Steven Dillon (2006). The Solaris Effect: Art and Artifice in Contemporary American Film. University of Texas Press. p. 265. ISBN 0292713452.

- ^ Raymond Aron (2000). The Century of Total War. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0861711734.

- ^ Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama (1954). The Meaning of Life: Buddhist Perspectives on Cause and Effect. Doubleday. p. 379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d George Cappannelli; Sedena Cappannelli (2004). Authenticity: Simple Strategies for Greater Meaning and Purpose at Work and at Home. Emmis Books. p. 256. ISBN 1578601487.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Michael Joachim Girard (2006). Essential Believing for the Christian Soul. Xulon Press. p. 324. ISBN 1597815969.

- ^ T. M. P. Mahadevan (1974). Philosophy: Theory and Practice (Proceedings of the International Seminar on World Philosophy). Centre for Advanced Study in Philosophy, University of Madras. p. 652.

- ^ Ernest Joseph Simmons (1973). Tolstoy. Routledge. p. 260. ISBN 071007395X.

- ^ Richard A. Bowell (2004). The Seven Steps Of Spiritual Intelligence: The Practical Pursuit of Purpose, Success and Happiness. Nicholas Brealey Publishing. p. 199. ISBN 1857883446.

- ^ John C. Gibbs; Karen S. Basinger; Dick Fuller (1992). Moral Maturity: Measuring the Development of Sociomoral Reflection. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 232. ISBN 0805804250.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Timothy Tang (2007). Real Answers to The Meaning of Life and Finding Happiness. iUniverse. p. 70. ISBN 9780595459414.

- ^ Tyler T. Roberts (1998). Contesting Spirit: Nietzsche, Affirmation, Religion. Princeton University Press. p. 256. ISBN 0691001278.

- ^ Lucy Costigan (2004). What Is the Meaning of Your Life: A Journey Towards Ultimate Meaning. iUniverse. p. 124. ISBN 0595338801.

- ^ Steven L. Jeffers; Harold Ivan Smith (2007). Finding a Sacred Oasis in Grief: A Resource Manual for Pastoral Care. Radcliffe Publishing. p. 188. ISBN 1846191815.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0802836348.

- ^ Dana A. Williams (2005). "In the Light of Likeness-transformed": The Literary Art of Leon Forrest. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0814209947.

- ^ Jerry Z. Muller (1997). Conservatism: An Anthology of Social and Political Thought from David Hume to the Present. Princeton University Press. p. 464. ISBN 0691037116.

- ^ a b Mary Nash; Bruce Stewart (2002). Spirituality and Social Care: Contributing to Personal and Community Well-being. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 256. ISBN 184310024X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xinzhong Yao (2000). An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. p. 362. ISBN 0521644305.

- ^ Bryan S. Turner; Chris Rojek (2001). Society and Culture: Principles of Scarcity and Solidarity. SAGE. p. 272. ISBN 0761970495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anil Goonewardene (1994). Buddhist Scriptures. Harcourt Heinemann. p. 48. ISBN 0435303554.

- ^ a b Luc Ferry (2002). Man Made God: The Meaning of Life. University of Chicago Press. p. 172. ISBN 0226244849.

- ^ a b c Eric G. Stephan; R. Wayne Pace (2002). Powerful Leadership: How to Unleash the Potential in Others and Simplify Your Own Life. FT Press. p. 225. ISBN 0130668362.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Mutual-aid Approach to Working with Groups: Helping People Help One Another. Haworth Press. 2004. ISBN 0789014629.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ John Caunt (2002). Boost Your Self-Esteem. Kogan Page. ISBN 0749438711.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j John Cook (2007). The Book of Positive Quotations. Fairview Press. p. 755. ISBN 1577491696.

- ^ Lee, Dong Yul (June 2000). "What Makes You Happy?: A Comparison of Self-reported Criteria of Happiness Between Two Cultures". Social Indicators Research. 50 (3): 351–362. doi:10.1023/A:1004647517069. ISSN 0303-8300. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Social perspectives, ACM Digital Library

- ^ John Kultgen (1995). Autonomy and Intervention: Parentalism in the Caring Life. Oxford University Press US. p. 280. ISBN 0195085310.

- ^ a b Steve Chandler (2005). Reinventing Yourself: How to Become the Person You've Always Wanted to Be. Career Press. p. 224. ISBN 1564148173.

- ^ a b John G. West (2002). Celebrating Middle-Earth: The Lord of the Rings as a Defense of Western Civilization. Inkling Books. p. 108. ISBN 1587420120.

- ^ Rachel Madorsky (2003). Create Your Own Destiny!: Spiritual Path to Success. Avanty House. p. 296. ISBN 0970534949.

- ^ Douglas Adams. The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. ISBN 0-330-25864-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help) - ^ Douglas Adams. Life, the Universe and Everything. ISBN 0-330-26738-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help) - ^ Douglas Adams (1 January 1980). The Restaurant at the End of the Universe. ISBN 0-345-39181-0.

- ^ Douglas Adams. So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish. ISBN 0-330-28700-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help) - ^ a b Monty Python's Completely Useless Web Site: Monty Python's The Meaning Of Life: Complete Script

- ^ Terry Burnham (2005). Mean Markets and Lizard Brains: How to Profit from the New Science of Irrationality. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0471716952.

- ^ Yolanda Fernandez (2002). In Their Shoes: Examining the Issue of Empathy and Its Place in the Treatment of Offenders. Wood 'N' Barnes Publishing. ISBN 1885473486.

- ^ Matt Lawrence (2004). Like a Splinter in Your Mind: The Philosophy Behind the Matrix Trilogy. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1405125241.

- ^ a b c d e Pregnant Pauses: Charlie & Lucy

- ^ AllGreatQuotes: Charlie Brown Quotes

- ^ Quote Details: Charles M. Schulz: That's the secret to life... replace one worry with another....

- ^ HamieNET.com [You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown] Happiness Lyrics

- ^ Quote Details: Charles M. Schulz: Life is like an ice cream cone...you have to lick it one day at a time.

- ^ AllGreatQuotes: Lucy Van Pelt Quotes

- ^ Chekhov Quote:You ask "What is life?" That is the same as asking "What is a carrot?" A carrot is a carrot and we know nothing more.

External links

General

- Meaningsoflife.com

- Meaningsoflife.tv – Video discussions on the ultimate meaning of life with various religious and philosophical leaders.

- Frequently Asked Questions about the Meaning of Life

- God's Will and The Meaning of Life: Creation is Love – A highly-trafficked blog-post which suggests simplifying and synthesizing the possibility of science and spiritual teachings being accurate... and then some.

- The Meaning of Life and other questions