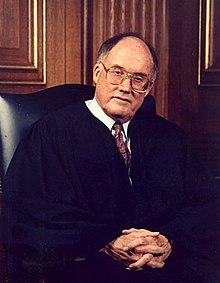

William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist | |

|---|---|

| |

| Preceded by | Warren E. Burger |

| Succeeded by | John Roberts |

William Hubbs Rehnquist (October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American lawyer, jurist and political figure, who served as an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1972 until 1986, and as the 16th Chief Justice of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2005. A stalwart proponent of federalism, his legacy includes the first modern limits on Congress's power under the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution.

Rehnquist served as a law clerk for Justice Robert H. Jackson and as Assistant Attorney General during the administration of President Richard Nixon. In 1971, Nixon nominated Rehnquist to the U.S. Supreme Court as an Associate Justice; Rehnquist took his seat in 1972. In 1986, Ronald Reagan elevated him to the position of Chief Justice. He went on to preside over the court as Chief Justice for 19 years until his death in 2005, making him the fourth-longest-serving Chief Justice after Melville Fuller, Roger Taney and John Marshall, and the longest-serving Chief Justice who had previously served as an Associate Justice.

Early life

Rehnquist was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and grew up in the suburb of Shorewood. He was the grandson of Swedish immigrants. His father, William Benjamin Rehnquist, was a paper salesman; his mother, Margery Peck Rehnquist, was a translator and homemaker. Rehnquist changed his middle name to Hubbs, his grandmother's maiden name, during his high school years.

After graduating from Shorewood High School in 1942, Rehnquist attended Kenyon College for one quarter in the fall of 1942, before entering the U.S. Army Air Forces. Rehnquist served in World War II from March, 1943 to 1946. He was put into a pre-meteorology program, and was assigned to Denison University until February, 1944, when the program was shut down. He served three months at Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City, three months in Carlsbad, New Mexico, and then went to Hondo, Texas for a few months. He was then chosen for another training program which began at Chanute Field, Illinois, and ended at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. The program was designed to teach the maintenance and repair of weather instruments. In the summer of 1945 he went overseas, and served as a weather observer in North Africa.

After the war ended, Rehnquist attended Stanford University with assistance under the provisions of the G.I. Bill. In 1948, he received a bachelor's degree and a master's degree in political science. In 1950, he went to Harvard University, where he received a master's degree in government. He returned later to the Stanford Law School, where he graduated in the same class as Sandra Day O'Connor, who would later serve alongside him on the Supreme Court. It has been said that Rehnquist graduated first in his class, probably based on the fact that Rehnquist was class valedictorian during graduation ceremonies, but Stanford's official position is that the law school did not rank students in 1952. Link to article . Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz has alleged that, while at Stanford, Rehnquist publicly engaged in bigoted acts such as goose-stepping and making a mocking "Heil Hitler" salute in front of Jewish student dormitories, although there is little evidence to support these claims.

Rehnquist went to Washington, D.C. to work as a law clerk for Justice Robert H. Jackson during the court's 1951–1952 terms. There, he wrote a memorandum arguing against school desegregation while the court was considering the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. Rehnquist later claimed that the memo was meant to reflect Jackson's views and not his own. Rehnquist’s memo, entitled “A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases,” defended the separate-but-equal doctrine embodied in the 1896 Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson. Rehnquist concluded that Plessy “was right and should be reaffirmed.” When questioned about the memos by the Senate Judiciary Committee in both 1971 and 1986, Rehnquist blamed his defense of segregation on the late Justice Jackson, testifying that his memo was meant to reflect the views of Justice Jackson. However, Justice Jackson ultimately voted in Brown, along with a unanimous Court, to strike down school segregation. According to law professor Mark Tushnet, Justice Jackson’s longtime legal secretary called Rehnquist’s Senate testimony an attempt to “smear[] the reputation of a great justice.” Rehnquist later admitted to defending Plessy in arguments with fellow law clerks. Rehnquist moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where he was in private law practice from 1953 to 1969. During these years, he was active in the Republican Party and served as a legal advisor to Barry Goldwater's 1964 presidential campaign. During the 1986 U.S. Senate hearings on his chief justice nomination, several people came forward to complain about what they viewed as Rehnquist's attempts to discourage minority voters in Arizona elections when Rehnquist served as a "poll watcher" in the early 1960's. Rehnquist denied the charges.

Justice Department and Supreme Court service

When President Richard Nixon was elected in 1968, Rehnquist returned to work in Washington. He served as Assistant Attorney General of the Office of Legal Counsel, from 1969 to 1971. In this role, he served as the chief lawyer to Attorney General John Mitchell. President Nixon mistakenly referred to him as "Renchburg" in several of the tapes of Oval Office conversations revealed during the Watergate investigations. Because he was well-placed in the Justice Department, Rehnquist was mentioned for many years as a possibility for the source known as Deep Throat during the Watergate scandal. Bob Woodward's May 31, 2005, disclosure that W. Mark Felt was Deep Throat put these claims to rest.

Nixon nominated Rehnquist to replace John Marshall Harlan II on the Supreme Court upon Harlan's retirement, and after being confirmed by the Senate by a 68–26 vote on December 10, 1971, Rehnquist took his seat as an Associate Justice on January 7, 1972. There were two vacancies on the court at the time; Nixon nominated Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr. to fill the other.

On the Burger Court, Rehnquist promptly established himself as the most conservative of Nixon's appointees, taking a narrow view of the Fourteenth Amendment and a broad view of state power. He voted against the expansion of school desegregation plans and the establishment of legalized abortions (dissenting in the 1973 case Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973)) and in favor of school prayer, capital punishment and states' rights.

Rehnquist wrote the decision Diamond v. Diehr, which punched a hole in the dike against software patents in the United States erected by Justice Stevens in Parker v. Flook; the dike collapsed within a few years and software patenting is now virtually unlimited. In Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., pertaining to video cassette recorders such as the Betamax system, Justice Stevens again wrote an opinion providing a broad fair use doctrine while Rehnquist joined the dissent, which supported stronger copyrights. Years later, in Eldred v. Ashcroft, Rehnquist was in the majority favoring the copyright holders, with Justice Stevens dissenting in favor of a narrower construction of copyright law.

When Chief Justice Warren Burger retired in 1986, then-President Ronald Reagan nominated Rehnquist to fill the position. During confirmation hearings, Senator Edward Kennedy challenged Rehnquist on his ownership of property that had a restrictive covenant against sale to Jews; such covenants are unenforceable under Shelley v. Kraemer. Despite this and other controversies, the Senate confirmed his appointment by a 65–33 vote, and he assumed the office on September 26. Rehnquist's associate justice seat was filled by Antonin Scalia.

After becoming Chief Justice, Rehnquist continued to lead the Court toward a broader view of state powers in the U.S. federal system. For example, he wrote for a 5-to-4 majority in United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995), striking down a federal law as exceeding congressional power under the commerce clause. Rehnquist also led the way in establishing more governmental leniency towards state aid for religion, writing for another 5-to-4 majority in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002), approving a school voucher program that aided parochial schools along with other private schools.

In 1999, Rehnquist became the second Chief Justice (after Salmon P. Chase) to preside over a presidential impeachment trial, during the proceedings against President Bill Clinton. In 2000, Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion in Bush v. Gore, effectively awarding the Presidency to George W. Bush.

Poor health on the Supreme Court

On October 26, 2004, the Supreme Court announced that Rehnquist had recently been diagnosed with thyroid cancer. Because of his health problems, there were doubts as to whether he would be able to administer the oath of office to President George W. Bush at his second inauguration on January 20, 2005. However, Rehnquist did swear in Bush at the inaugural; he arrived using a cane, walked very slowly, and left immediately after the oath itself was administered.

After missing 44 oral arguments before the Court in late 2004 and early 2005, Rehnquist appeared on the bench again on March 21. During his absence, however, he remained involved in the business of the Court, participating in many of the decisions and deliberations made.

On July 1, Rehnquist's colleague Sandra Day O'Connor announced her retirement from her position of Associate Justice, after consulting with Rehnquist and learning that he intended to remain on the Court. Commenting on the frenzy of speculation over his retirement, Rehnquist joked with the press, "That's for me to know and you to find out."

Death

Rehnquist died at his Arlington, Virginia, home on September 3, 2005, at the age of 80, after a long battle with thyroid cancer. Rehnquist was the first member of the Supreme Court to die in office since Justice Robert H. Jackson in 1954, and the first Chief Justice to die in office since Fred M. Vinson, in 1953.

On September 6, 2005, eight of Rehnquist's former law clerks served as his pallbearers as his casket was placed on the same catafalque that bore Abraham Lincoln's casket as he lay in state in 1865. [1]

Rehnquist's body remained in the Great Hall of the Supreme Court until his funeral on September 7, 2005, a Lutheran service conducted at the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington, D.C. He was eulogized by President Bush and Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, as well as by members of his family. [2] His funeral was followed by a private burial service, in which he was interred next to his late wife, Nan, at Arlington National Cemetery [3].

Succession as Chief Justice

The vacancy left by Rehnquist's death came just over two months after Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's July 1, 2005, announcement that she would retire from the Court, leaving two vacancies to be filled by President George W. Bush (though O'Connor will remain on the bench until the confirmation of her successor).

On September 5, 2005, President Bush withdrew the Associate Justice nomination of Judge John Roberts of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, and instead nominated him to replace Rehnquist as Chief Justice. Roberts was confirmed by the U.S. Senate and sworn in as the new Chief Justice on September 29, 2005. Roberts had clerked for Rehnquist in 1980-1981, and was a pallbearer at Rehnquist's funeral.

Family life

- Rehnquist's paternal grandparents immigrated separately (although they may have known one another before) from Sweden in 1880. His grandfather Olof Andersson, who changed from the patronymic Andersson to the family name Rehnquist, was born in the province of Värmland and his grandmother was born Adolfina Ternberg in Vretakloster (parish) in Östergötland. Rehnquist is one of only two Chief Justices of Swedish descent, the other being Earl Warren, who had Norwegian-Swedish ancestry.

- Rehnquist’s maternal lineage traces back via New York to the Pilgrims and other early New England settlers.

- Rehnquist married Natalie "Nan" Cornell on August 29, 1953. She died on October 17, 1991, after suffering from ovarian cancer. The couple had three children: James, Janet and Nancy. Janet Rehnquist is a former Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services.

- Rehnquist often spent summers in Vermont.

Trivia

- Rehnquist added four gold stripes to the sleeves of his robe in 1995, after viewing a production of Gilbert and Sullivan's Iolanthe and being inspired by the costume of the Lord Chancellor. In her remarks at his funeral, Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor said he told her the four gold stripes were "one for every five years" he had been a justice, but he never added more. His successor, Chief Justice John Roberts, did not continue the practice (view this Reuters photo).

- Rehnquist was born on exactly the same day as former President Jimmy Carter.

Books written by Rehnquist

- . ISBN 0375413871.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0375409432.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0688051421.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0679446613.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help)

References

- Molotsky, Irvin. "Doctor Says Pain Drug Caused Justice Rehnquist to Slur His Speech." The New York Times, January 2, 1982. p. 9.

- Lane, Charles. "Chief Justice Dies at Age 80." The Washington Post, September 4, 2005. p. A01.

External links

- Supreme court official bio (PDF)

- 1969 memo on FOIA policy.

- Remarks of the Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, Swedish Colonial Society's annual luncheon league, Philadelphia, April 9, 2001

- Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist Dies - The Washington Post

- Legacy of William H. Rehnquist - Majority and Dissenting Opinions in Major Supreme Court Cases

- Emotion Overcomes Court at Goodbye to 'the Chief' The Washington Post

- The Rehnquist Legacy: 33 Years Turning Back the Court - The Washington Post

- Supreme Court Justice Rehnquist's Key Decisions - The Washington Post

- Tributes from fellow Supreme Court justices

- Supreme Court Chief Justice Rehnquist Dies - The New York Times

- Chief Justice Rehnquist Dies at 80 - The New York Times

- William H. Rehnquist Dies at 80; Led Conservative Revolution on Supreme Court - The New York Times

- The Legacy of Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist - The New York Times

- Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist Dead - Fox News

- Chief Justice Rehnquist has died - CNN

- Supreme Court Press Release RE: Funeral Arrangements

- CSPAN article explaining the four gold stripes

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1972-1975 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1975-1981 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1981-1986 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1986-1987 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1988-1990 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1990-1991 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1991-1993 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1993-1994 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1994-2005 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition