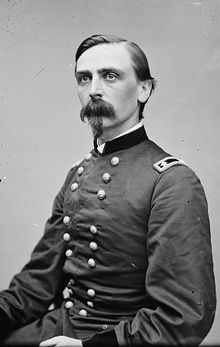

Adelbert Ames

Adelbert Ames | |

|---|---|

General, Governor and Senator from Mississippi | |

| 30th Governor of Mississippi | |

| In office January 4, 1874 – March 20, 1876 | |

| Preceded by | Ridgley C. Powers |

| Succeeded by | John M. Stone |

| 27th Governor of Mississippi | |

| In office June 15, 1868 – March 10, 1870 | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin G. Humphreys |

| Succeeded by | James L. Alcorn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 31, 1835 Rockland, Maine |

| Died | April 12, 1933 (aged 97) Ormond Beach, Florida |

| Resting place | Hildreth Family Cemetery Lowell, Massachusetts 42°39′39″N 71°18′36″W / 42.660798°N 71.309928°W |

| Political party | Republican |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Profession | Military |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–70, 1898–99 |

| Rank | Brevet Major General |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War Spanish-American War |

Adelbert Ames (October 31, 1835– April 12, 1933) was an American sailor, soldier, and politician. He served with distinction as a Union Army general during the American Civil War, was a politician in Reconstruction-era Mississippi, and then served as a United States Army general during the Spanish-American War.

Ames is also noted as the last general officer of the American Civil War to die, passing away at age 97 in 1933.[1]

Early life and career

Adelbert (Template:PronEng ə-DEL-bərt)[2] Ames was born in 1833 in the town of Rockland, located in Knox County, Maine. He was the son of a sea captain named Jesse Ames.[3] Adelbert Ames also grew up to be a sailor, becoming a mate on a clipper ship,[4] and also served briefly as a merchant seaman on his own father's ship.

On July 1, 1856, he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, and was still there when the American Civil War began in 1861.[5]

Civil War service

Ames graduated from the United States Military Academy on May 6, 1861, standing fifth in his class of 45. On that same date he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery. Eight days later he was promoted to first lieutenant and was assigned to the 5th U.S. Artillery.[5] During the First Battle of Bull Run that July, Ames was badly wounded in the right thigh but refused to leave his guns.[6] He was brevetted to the rank of major on July 21 for his actions during Bull Run. In 1893 Ames would also received the Medal of Honor due to his performance there.[7]

Returning to duty the following spring, Ames was part of the defenses of Washington, D.C..[8] He then fought in the Peninsula Campaign, and saw action at the Battle of Yorktown from April 5 to May 4, the Battle of Gaines' Mill on June 27, and the Battle of Malvern Hill that July. Ames was commended for his conduct at Malvern Hill by Col. Henry J. Hunt, chief of the artillery of the Army of the Potomac, and he received a brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel on July 1.[5]

Although Ames was becoming an excellent artillery officer, he realized that significant promotions would be available only in the infantry. He returned to Maine and politicked to receive a commission as a regimental commander of infantry and was assigned to command the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment on August 20, 1862.[5] The 20th Maine fought in the Maryland Campaign, but saw little action at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, while in a reserve capacity. During the Union defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg that winter, Ames led his regiment in one of the last charges on December 13 against Marye's Heights. During the Chancellorsville Campaign in May 1863, Ames volunteered as an aide-de-camp to Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commander of the V Corps.

Probably as a result of this staff duty and his proximity to the influential Meade,[citation needed] Ames was promoted to brigadier general in the Union Army on May 20, 1863, two weeks following the Battle of Chancellorsville.[5] Ames assumed brigade command in the XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac, relinquishing his command of the 20th Maine to Lt. Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain, who would soon lead the regiment to fame in the Battle of Gettysburg that July.[9]

While his own experience at Gettysburg did not achieve the renown of Chamberlain's, Ames performed well under difficult circumstances. During the massive assault by Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell on July 1, 1863, Ames' division commander, Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow, moved his division well in front of other elements of the XI Corps to a slight rise that is now known as Barlow's Knoll. This salient position was quickly overrun, and Barlow was wounded and captured. Ames took command of the division and led it in retreat through the streets of Gettysburg to a position on Cemetery Hill. On July 2, the second day of battle, Ames' battered division bore the brunt of the assault on East Cemetery Hill by Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early, but was able to hold the critical position with help from surrounding units. At one point Ames himself took part in the hand-to-hand fighting. After the battle, the men of the 20th Maine presented Ames with their battle flag as a token of their esteem.

After the battle, Ames reverted to brigade command with a brevet promotion to colonel in the regular army. His division, under the command of Brig. Gen. George H. Gordon, was transferred to the Department of the South, where it served in actions in South Carolina and Florida.

In 1864, Ames' division, now part of the X Corps of the Army of the James, served under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Butler in the Bermuda Hundred Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg. In the future, he would become Butler's son-in-law. That winter, the division was reassigned to the XXIV Corps and sent to North Carolina.

During the two years following his service in the Army of the Potomac, Ames shifted between brigade and division command (and even led his corps on two occasions), though he generally can be identified as a division commander. He led the successful assault in the Battle of Fort Fisher (commanding the 2nd Division, XXIV Corps), accompanying his men into the formidable coastal fortress as most of his staff were shot down by Confederate snipers.[6] He received a brevet promotion to major general in the Union Army (and brigadier general in the regular army) on March 13, 1865, for his role in the battle.[10]

Mississippi politics, U.S. Senate

In 1868, Ames was appointed by Congress to be provisional Governor of Mississippi. His command soon extended to the Fourth Military District, which consisted of Mississippi and Arkansas.[11] During his administration, he took several steps to advance the rights of freed slaves, appointing the first black office-holders in state history. White supremacist violence was prevalent in the state, one of the last to comply with Reconstruction, but a general election was held during his tenure in 1869 and the legislature convened at the beginning of the following year.[3]

The Mississippi Legislature elected Ames to the U.S. Senate after the readmission of Mississippi to the Union; he served from February 24, 1870 to January 10, 1874, as a Republican.[3][11] In Washington, Ames met and married Blanche Butler, daughter of his former commander, and now U.S. Representative, Benjamin Butler, on July 20, 1870. They had six children including Adelbert Ames Jr. and Butler Ames.[3] As a Senator, Ames became a talented public speaker to the point where even some of his Democratic opponents acknowledged his ability.[3]

In the Senate, Ames was chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Enrolled Bills.[11] Upon being elected governor of Mississippi, he resigned his seat to assume his duties.[3] He experienced a great deal of resentment from Democratic Party supporters even before taking office in 1874; a riot broke out in Vicksburg in December 1873 that started a series of reprisals against many Republican supporters, the vast majority of them black.[3] As the state election of 1875 approached, the Democrats organized an armed insurrection to unseat the black-supported Republican government. Armed attacks on Republican activists proliferated, and Governor Ames appealed to the federal government for assistance, which was refused. That November, Democrats gained firm control of both houses of the legislature. Ames requested the intervention of the U.S. Congress since he believed that the election was full of voter intimidation and fraud. The state legislature, convening in 1876, drew up articles of impeachment against him and all statewide officials. He resigned a few months after the legislature agreed to drop the articles against him.[3]

Later life

After leaving office, Ames settled briefly in Northfield, Minnesota, where he joined his father and brother in their flour-milling business. During his residence there, in September 1876, Jesse James and his gang of former Confederate guerrillas raided the town's bank, largely because of Ames' (and controversial Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler's) investment in it, but failed in their attempt to rob it. Ames next headed to New York City, then later settled in Lowell, Massachusetts, as an executive in a flour mill, along with other business interests.[11]

In 1898, he was appointed brigadier general of volunteers in the Spanish-American War and fought in Cuba.[11] Several years afterward, he retired from business pursuits in Lowell. Ames corresponded extensively with the historian James Wilford Garner during this period; Garner's dissertation viewed Reconstruction as "unwise," but absolved Ames of personal corruption[12].

Ames' widow compiled a collection of her correspondence with Ames, Chronicles from the Nineteenth Century, published posthumously in 1957, and his daughter Blanche Ames Ames (she married into another Ames family) published a biography, Adelbert Ames, in 1964.

Ames died in 1933 at the age of 97 in his winter home, located in Ormond Beach, Florida, next to the estate of his friend John D. Rockefeller. At the time of his death, he was the last surviving general who had served in the Civil War. He was the father of the noted scientist Adelbert Ames, Jr. and Blanche Ames Ames, noted suffragist, inventor, artist, and writer. Blanche was her father's biographer; the mansion she designed and had built is now part of Borderland State Park in Massachusetts. Adelbert Ames was also the great-grandfather of George Plimpton. Ames is buried in the Hildreth family cemetery—the family of his mother-in-law, Sarah Hildreth Butler—behind the main cemetery (also known as Hildreth Cemetery) on Hildreth Street in Lowell.[13] The world's largest cargo vessel of the 19th century, the schooner Governor Ames, was named after him.

John F. Kennedy, through George Plimpton, is indirectly responsible for a full-length biography of General Ames. In Profiles in Courage, Kennedy relied on Jim Crow-era historical texts to produce a brief but devastating portrait of Ames's administration of Mississippi. Ames's daughter Blanche, a formidable figure in Massachusetts, bombarded the then-senator with letters complaining about the depiction, and continued her barrage after Kennedy entered the White House. President Kennedy then turned to his friend Plimpton to tell Blanche, Plimpton's grandmother, that she was "interfering with state business." Her response was to write her own book about her father. In the years since Profiles in Courage was published, historical opinion has shifted, and Ames's role as a politician in Mississippi is viewed far more favorably.

In popular media

Ames was portrayed by Matt Letscher in the movie adaptation of Jeffrey Shaara's Gods and Generals. He is a character in the alternate history novel Gettysburg, written by Newt Gingrich and William Forstchen. He is also the main focus of the historical work Redemption by Nicholas Lehmann.

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and Organization: First Lieutenant, 5th U.S. Artillery. Place and Date: At Bull Run, Va., July 21, 1861. Entered Service At: Rockland, Maine. Birth: East Thomaston, Maine. Date of Issue: June 22, 1894.

Citation:

Remained upon the field in command of a section of Griffin's Battery, directing its fire after being severely wounded and refusing to leave the field until too weak to sit upon the caisson where he had been placed by men of his command.[14]

See also

- List of Medal of Honor recipients

- List of American Civil War Medal of Honor recipients: A-F

- List of American Civil War generals

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

- Ames, Blanche, Adelbert Ames, 1835-1933; General, Senator, Governor, the story of his life and times and his integrity as a soldier and statesman in the service of the United States of America throughout the Civil War and in Mississippi in the years of Reconstruction, Argosy-Antiquarian, 1964.

- Budiansky, Stephen, The Bloody Shirt: Terror After Appomattox, Viking Adult, 2008, ISBN 978-0670018406.

- Current, Richard Nelson, Those Terrible Carpetbaggers: A Reinterpretation, Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Nevins, Allan, ed., A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861-1865, Da Capo, 1998.

- Quigley, Robert D., Civil War Spoken Here: A Dictionary of Mispronounced People, Places and Things of the 1860s, C.W. Historicals, 1993, ISBN 0-9637745-0-6.

- Stiles, T.J., Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War, Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

- Tagg, Larry, The Generals of Gettysburg, Savas Publishing, 1998, ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Blue: The Lives of the Union Commanders, Louisiana State University Press, 1964, ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- findagrave.com Find-a-grave entry for Ames.

Notes

- ^ Warner, p. 6, "This last survivor of the full-rank general officers on either side of the conflict ..."; Eicher, p. 103, "... the last surviving substantive Civil War general officer."

- ^ Quigley, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Budiansky, pp. 64, 99.

- ^ Warner, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Eicher, p. 102.

- ^ a b Budiansky, p. 65.

- ^ Eicher, p. 102; Warner, p. 5.

- ^ Warner, p. 6.

- ^ "Adelbert Ames". findagrave.com. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ Eicher, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d e "AMES, Adelbert". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

- ^ Lemann, Nicholas (2007). Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. Macmillan. ISBN 0374530696, 9780374530693.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Hildreth Family Cemetery". findagrave.com. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ^ "U.S. Army Center of Military History Medal of Honor Citations Archive". American Medal of Honor recipients for the American Civil War (A-L). June 8, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher Army Medal of Honor website" ignored (help)

External links

- United States Congress. "Adelbert Ames (id: A000172)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2008-02-15

- Maine state archives: 20th Maine Battle Flag

- A photocopy of a published speech by Adelbert Ames is available at The University of Mississippi, Archives and Special Collections in the Small Manuscript Collection (MUM00400).

- Adelbert Ames's account of his role during the James-Younger gang's raid on the First National Bank of Northfield, Minnesota, in 1876.

- Biography of Blanche Ames Ames

- Home of Heroes

- History Central

- 1835 births

- 1933 deaths

- People from Knox County, Maine

- Union Army generals

- Army Medal of Honor recipients

- Governors of Mississippi

- American military personnel of the Spanish–American War

- United States Army generals

- United States Senators from Mississippi

- United States Military Academy alumni

- People of Maine in the American Civil War

- People from Volusia County, Florida

- American Episcopalians

- English Americans